A Final Note Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator on Shabbat

A Final Note

Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator on

Shabbat

Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator on

Shabbat

By Yaacov Sasson

The purpose of this note is to

establish conclusively that Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer, the Dayan of Brisk,

never permitted opening a refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go

on. I was deeply disappointed to read Rabbi Michael Broyde’s response[1] to

my “Note Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator

on Shabbat.”[2] In

short, R. Broyde has incorrectly asserted that Rav Simcha Zelig permitted

opening a refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go on. In truth,

Rav Simcha Zelig permitted opening a refrigerator when the motor will go on; he never addressed the refrigerator light at all. Rather than admit to this

simple mistake, R. Broyde has chosen to reiterate his basic error and compound

it with further errors. Furthermore, R. Broyde has entirely ignored the crux of

my own argument, specifically that the articles to which Rav Simcha Zelig was

responding were about triggering the refrigerator motor by allowing warm

air to enter. Those articles do not mention refrigerator lights at all. It is

therefore untenable to claim that Rav Simcha Zelig permitted opening a

refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go on.

establish conclusively that Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer, the Dayan of Brisk,

never permitted opening a refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go

on. I was deeply disappointed to read Rabbi Michael Broyde’s response[1] to

my “Note Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator

on Shabbat.”[2] In

short, R. Broyde has incorrectly asserted that Rav Simcha Zelig permitted

opening a refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go on. In truth,

Rav Simcha Zelig permitted opening a refrigerator when the motor will go on; he never addressed the refrigerator light at all. Rather than admit to this

simple mistake, R. Broyde has chosen to reiterate his basic error and compound

it with further errors. Furthermore, R. Broyde has entirely ignored the crux of

my own argument, specifically that the articles to which Rav Simcha Zelig was

responding were about triggering the refrigerator motor by allowing warm

air to enter. Those articles do not mention refrigerator lights at all. It is

therefore untenable to claim that Rav Simcha Zelig permitted opening a

refrigerator on Shabbat when the light inside will go on.

Let us proceed to examine how

each argument advanced by R. Broyde is incorrect. Below are direct quotations

from R. Broyde’s response (in bold), followed by my own comments.

each argument advanced by R. Broyde is incorrect. Below are direct quotations

from R. Broyde’s response (in bold), followed by my own comments.

“The relevant paragraph of the

teshuva by Dayan Rieger reads simply:

teshuva by Dayan Rieger reads simply:

ובדבר התבת

קרח מלאכותי נראה כיון דכשפותח את דלת התיבה הוא כדי לקבל משם איזו דבר ואינו

מכוין להדליק את העלעקטרי הוי פסיק רישיה דלא איכפת ליה אפילו להדליק אם הוא באופן

שהוא פסיק רישיה.

קרח מלאכותי נראה כיון דכשפותח את דלת התיבה הוא כדי לקבל משם איזו דבר ואינו

מכוין להדליק את העלעקטרי הוי פסיק רישיה דלא איכפת ליה אפילו להדליק אם הוא באופן

שהוא פסיק רישיה.

And in the matter of the artificial [electric]

icebox it appears that since when one opens the door of the box to get

something from there and does not intend to ignite (light) the electricity it

is a psik resha that he does not care about, even to light in way that

is a psik resha.”

icebox it appears that since when one opens the door of the box to get

something from there and does not intend to ignite (light) the electricity it

is a psik resha that he does not care about, even to light in way that

is a psik resha.”

R. Broyde’s citation has omitted the first several words of the paragraph,

which read as follows[3]:

which read as follows[3]:

הגיעני השלשה

כרכים הפרדס ובדבר התבת קרח מלאכותי…

כרכים הפרדס ובדבר התבת קרח מלאכותי…

“I received the three issues of Hapardes and in the

matter of the artificial [electric] icebox…”

matter of the artificial [electric] icebox…”

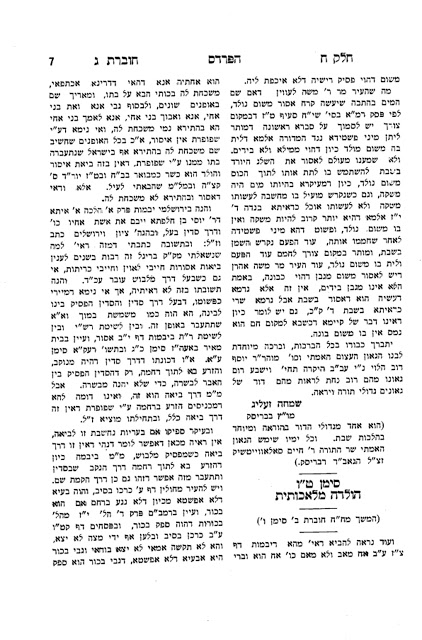

This omission is significant, because these words make clear that Rav

Simcha Zelig was addressing the refrigerator question raised in earlier issues

of Hapardes. (See Hapardes 1931 num. 2 page 3, and Hapardes

1931 num. 3 page 7.) The question under discussion in those previous volumes was

the triggering of the refrigerator motor, and not the light, as noted.

Simcha Zelig was addressing the refrigerator question raised in earlier issues

of Hapardes. (See Hapardes 1931 num. 2 page 3, and Hapardes

1931 num. 3 page 7.) The question under discussion in those previous volumes was

the triggering of the refrigerator motor, and not the light, as noted.

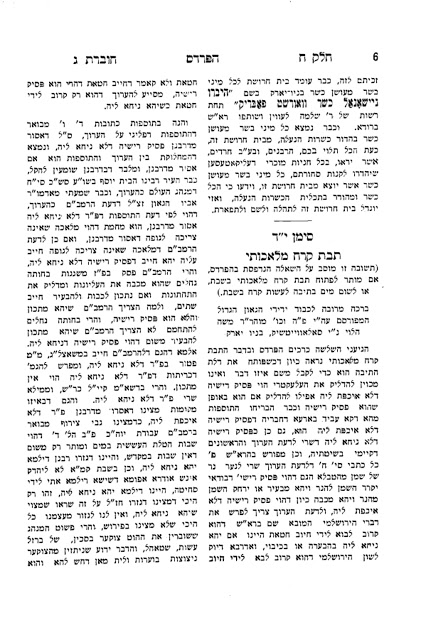

Also of note, is that at the end of his teshuva[4],

Rav Simcha Zelig addressed Rav Moshe Levin’s question regarding the

permissibility of making ice on Shabbat. Rav Simcha Zelig cited this question

specifically in the name of Rav Levin. This is significant because the ice question

appeared in the name of Rav Levin in Hapardes 1931 num. 3 page 7, in

an article about triggering the refrigerator motors.[5] See

the final paragraph of the article titled “Frigidaire” in the image below:

Rav Simcha Zelig addressed Rav Moshe Levin’s question regarding the

permissibility of making ice on Shabbat. Rav Simcha Zelig cited this question

specifically in the name of Rav Levin. This is significant because the ice question

appeared in the name of Rav Levin in Hapardes 1931 num. 3 page 7, in

an article about triggering the refrigerator motors.[5] See

the final paragraph of the article titled “Frigidaire” in the image below:

So it is clear that Rav Simcha Zelig introduced his teshuva with a reference to the prior issues of Hapardes. And

it is also clear that he closed his teshuva by addressing Rav Moshe

Levin’s ice question from Hapardes (which appeared in the article

entitled “Frigidaire”, shown above, about the refrigerator motors.) R. Broyde

apparently contends that in between, Rav Simcha Zelig veered off to address an

unrelated question which never appeared in Hapardes (that of the

refrigerator light), without ever addressing the question of the

refrigerator motor itself. And he did this while directly addressing the

ice question from the article entitled “Frigidaire”, but never addressed the

main substance of that article, the refrigerator motor. The absurdity of this

position is self-evident.

it is also clear that he closed his teshuva by addressing Rav Moshe

Levin’s ice question from Hapardes (which appeared in the article

entitled “Frigidaire”, shown above, about the refrigerator motors.) R. Broyde

apparently contends that in between, Rav Simcha Zelig veered off to address an

unrelated question which never appeared in Hapardes (that of the

refrigerator light), without ever addressing the question of the

refrigerator motor itself. And he did this while directly addressing the

ice question from the article entitled “Frigidaire”, but never addressed the

main substance of that article, the refrigerator motor. The absurdity of this

position is self-evident.

Also of note is the introductory paragraph to Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva,

presumably written by the editor, Rav Shmuel Pardes, which reads as follows[6]:

presumably written by the editor, Rav Shmuel Pardes, which reads as follows[6]:

תשובה זו מוסב על

השאלה הנדפסת בהפרדס, אם מותר לפתוח תבת קרח מלאכותי בשבת, או לשום מים בתיבה

לעשות קרח בשבת.

השאלה הנדפסת בהפרדס, אם מותר לפתוח תבת קרח מלאכותי בשבת, או לשום מים בתיבה

לעשות קרח בשבת.

This teshuva addresses the question that

was printed in Hapardes, whether it is permitted to open a refrigerator

on Shabbat, or to put water inside the refrigerator (freezer) to make ice on

Shabbat.

was printed in Hapardes, whether it is permitted to open a refrigerator

on Shabbat, or to put water inside the refrigerator (freezer) to make ice on

Shabbat.

Rav Pardes clearly understood and presented Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva

to be addressing the question of triggering the motor, which had been raised in

earlier issues of Hapardes.

to be addressing the question of triggering the motor, which had been raised in

earlier issues of Hapardes.

Furthermore, R. Broyde’s translation of Rav Simcha Zelig’s words is inaccurate,

and the effect of this mistranslation permeates his entire response. The

closing words of Rav Simcha Zelig in the paragraph cited by R. Broyde are:

and the effect of this mistranslation permeates his entire response. The

closing words of Rav Simcha Zelig in the paragraph cited by R. Broyde are:

הוי

פסיק רישיה דלא איכפת ליה אפילו להדליק אם הוא באופן שהוא פסיק רישיה.

פסיק רישיה דלא איכפת ליה אפילו להדליק אם הוא באופן שהוא פסיק רישיה.

R. Broyde has translated these words as:

“…it is a psik resha that he does not care

about, even to light in way that is a psik resha.”

about, even to light in way that is a psik resha.”

The astute reader will notice that the bolded words in the Hebrew citation

are left untranslated by R. Broyde, essentially ignored, as if they do not

exist. The closing words of this sentence are correctly translated as follows: even

to light IF IT IS in a way that is a psik reisha. Most of R. Broyde’s

response revolves around the incorrect assertion that since Rav Simcha Zelig

referenced a psik reisha, he must have been referring to igniting the

light, which is a psik reisha, and not the motor, which is not a psik

reisha. However, correctly translated, Rav Simcha Zelig says that opening

the refrigerator is permitted EVEN IF there is a psik reisha involved.

Such conditional language is entirely out of place when referring to a light,

which is certainly a psik reisha. This conditional language is only applicable

to the refrigerator motor, because there are times when, unbeknownst to the

person, the opening of the refrigerator door will immediately trigger the motor

to go on because of the already heightened initial air temperature inside the

refrigerator. (Such a situation is known in the language of the Poskim

as a “Safek psik resha”, as noted in Hapardes 1931 num. 3 page 6

regarding the refrigerator motor. It is the subject of dispute whether such an

action is permissible, similar to a Davar Sheaino Mitkavein, or

prohibited like a psik reisha.) Rav Simcha Zelig’s qualification that it

is permitted to open the refrigerator door even IF the situation is one of psik

reisha makes clear that he is referring to the refrigerator motor, contrary

to R. Broyde’s misreading.[7]

are left untranslated by R. Broyde, essentially ignored, as if they do not

exist. The closing words of this sentence are correctly translated as follows: even

to light IF IT IS in a way that is a psik reisha. Most of R. Broyde’s

response revolves around the incorrect assertion that since Rav Simcha Zelig

referenced a psik reisha, he must have been referring to igniting the

light, which is a psik reisha, and not the motor, which is not a psik

reisha. However, correctly translated, Rav Simcha Zelig says that opening

the refrigerator is permitted EVEN IF there is a psik reisha involved.

Such conditional language is entirely out of place when referring to a light,

which is certainly a psik reisha. This conditional language is only applicable

to the refrigerator motor, because there are times when, unbeknownst to the

person, the opening of the refrigerator door will immediately trigger the motor

to go on because of the already heightened initial air temperature inside the

refrigerator. (Such a situation is known in the language of the Poskim

as a “Safek psik resha”, as noted in Hapardes 1931 num. 3 page 6

regarding the refrigerator motor. It is the subject of dispute whether such an

action is permissible, similar to a Davar Sheaino Mitkavein, or

prohibited like a psik reisha.) Rav Simcha Zelig’s qualification that it

is permitted to open the refrigerator door even IF the situation is one of psik

reisha makes clear that he is referring to the refrigerator motor, contrary

to R. Broyde’s misreading.[7]

“A careful reader of the first sentence, and indeed of the entire teshuva,

can sense that there is some ambiguity here about the electrical object

referred to, since Dayan Rieger does not specify the source or consequence of

igniting the electricity.”

can sense that there is some ambiguity here about the electrical object

referred to, since Dayan Rieger does not specify the source or consequence of

igniting the electricity.”

There is no ambiguity to anyone who has seen the previous issues of Hapardes

which deal with the question of the refrigerator motor. There can only be

ambiguity if one reads Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva

entirely out of context, without looking at the articles to which he was

responding.

which deal with the question of the refrigerator motor. There can only be

ambiguity if one reads Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva

entirely out of context, without looking at the articles to which he was

responding.

“Particularly in the Yiddish spoken culture of that time, the term

“electric” seems to have meant “lights” and not electricity or motor.”

“electric” seems to have meant “lights” and not electricity or motor.”

R. Broyde’s assertion that “electri[c]” did not mean electricity or motor is

incorrect. See for example, the language in Rav Shlomo Heiman’s letter (dated

Erev Sukkot 5697/1936), printed in Chosen Yosef[8], and

reprinted in later editions of Chiddushei Rav Shlomo:

incorrect. See for example, the language in Rav Shlomo Heiman’s letter (dated

Erev Sukkot 5697/1936), printed in Chosen Yosef[8], and

reprinted in later editions of Chiddushei Rav Shlomo:

פקפק כת”ר

שליט”א בענין פתיחת הפרידזידעיר על העלעקטרי דע”י פתיחתו הוא

מבעיר העלעקטרי ורוצים להתיר על פי שטת הערוך דהוי פס”ר דלנ”ל

דיותר נוח לו שלא יכנס שם אויר קר, ולא יעלו לו הוצאות העלעקטרי…

שליט”א בענין פתיחת הפרידזידעיר על העלעקטרי דע”י פתיחתו הוא

מבעיר העלעקטרי ורוצים להתיר על פי שטת הערוך דהוי פס”ר דלנ”ל

דיותר נוח לו שלא יכנס שם אויר קר, ולא יעלו לו הוצאות העלעקטרי…

In this short excerpt, Rav Shlomo Heiman uses “elektri” to refer to

both the refrigerator motor and to electricity. Rav Heiman was clearly discussing

the permissibility of opening the door and triggering the refrigerator motor,

and refers to triggering the motor as kindling the “elektri”, the same

exact term used by Rav Simcha Zelig. Rav Heiman further notes that this is

considered “lo nicha lei” because the person would prefer to save the

additional expense of “elektri”, i.e. electricity.

both the refrigerator motor and to electricity. Rav Heiman was clearly discussing

the permissibility of opening the door and triggering the refrigerator motor,

and refers to triggering the motor as kindling the “elektri”, the same

exact term used by Rav Simcha Zelig. Rav Heiman further notes that this is

considered “lo nicha lei” because the person would prefer to save the

additional expense of “elektri”, i.e. electricity.

See also the words of Rav Chaim Fishel Epstein, in Teshuva Shleima

vol. 2 – Orach Chaim, beginning of Siman

6[9]:

vol. 2 – Orach Chaim, beginning of Siman

6[9]:

נשאלתי בדבר

המכונה המקררת בכח חשמל שקורין ריפרידזשיאטר, שבעת שפותחים הדלת נכנס אויר חם ואז

נתעורר כח החשמל (עלעקטריק בלע”ז) והמכונה מתחלת להניע ולעבוד כדי להוסיף

קרירות…

המכונה המקררת בכח חשמל שקורין ריפרידזשיאטר, שבעת שפותחים הדלת נכנס אויר חם ואז

נתעורר כח החשמל (עלעקטריק בלע”ז) והמכונה מתחלת להניע ולעבוד כדי להוסיף

קרירות…

Here, Rav Epstein synonymizes koach chashmal, or electricity, with “עלעקטריק”.

See also Hapardes 1931, num. 2 page 3, where zerem hachashmali, or

electric current, is synonymized with

“עלעקטריק”. R. Broyde’s contention that “electri[c]”

did not mean electricity or motor is simply false.

electric current, is synonymized with

“עלעקטריק”. R. Broyde’s contention that “electri[c]”

did not mean electricity or motor is simply false.

“Elektri, according to

my colleague at Emory, Professor Nick Block, more likely means the light than

anything else in 1930s Yiddish.”

my colleague at Emory, Professor Nick Block, more likely means the light than

anything else in 1930s Yiddish.”

One need not be a Professor of German Studies to

recognize that within a discussion of

refrigerator motors, it is more than likely that “Elektri” means a

refrigerator motor, the subject under discussion, or its associated electricity.

This was true even in 1930s Yiddish spoken culture; see Rav Shlomo Heiman’s

1936 letter cited above.

recognize that within a discussion of

refrigerator motors, it is more than likely that “Elektri” means a

refrigerator motor, the subject under discussion, or its associated electricity.

This was true even in 1930s Yiddish spoken culture; see Rav Shlomo Heiman’s

1936 letter cited above.

Additionally, as mentioned above, Rav Pardes (editor of Hapardes)

clearly understood Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva to be addressing the

question of triggering the motor, which had been raised in earlier issues of Hapardes.

Rav Pardes’ knowledge of 1930s Yiddish was certainly robust.

clearly understood Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva to be addressing the

question of triggering the motor, which had been raised in earlier issues of Hapardes.

Rav Pardes’ knowledge of 1930s Yiddish was certainly robust.

“Second, and much more importantly, the halachic analysis presented by

Dayan Rieger addresses a direct action, while everyone else who discusses the

motor speaks about an indirect action…opening the door usually leads to an

increase of air temperature inside the refrigerator, which eventually directs

the motor to go on…many times when the refrigerator is opened, the motor does

not go on at all…But Dayan Rieger makes no mention of this…he assumes that when

the refrigerator door is opened the electrical object under discussion is always

ignited, and it does so immediately and directly, thus causing a melacha.

This is the formulation of psik resha, which inexorably causes melacha

each and every time…”

Dayan Rieger addresses a direct action, while everyone else who discusses the

motor speaks about an indirect action…opening the door usually leads to an

increase of air temperature inside the refrigerator, which eventually directs

the motor to go on…many times when the refrigerator is opened, the motor does

not go on at all…But Dayan Rieger makes no mention of this…he assumes that when

the refrigerator door is opened the electrical object under discussion is always

ignited, and it does so immediately and directly, thus causing a melacha.

This is the formulation of psik resha, which inexorably causes melacha

each and every time…”

This section is entirely wrong, and is predicated on R. Broyde’s

misreading/mistranslation of Rav Simcha Zelig’s words, as noted above. That Rav

Simcha Zelig added the qualification of “IF IT IS” a psik reisha renders R. Broyde’s words here to be entirely

irrelevant and incorrect. Rav Simcha Zelig’s language of “IF IT IS” a psik

reisha makes clear that he is assuming that the motor is not always

ignited by opening the door, but at times it might be ignited in a manner of psik

reisha, due to the heightened initial air temperature inside the

refrigerator. (Again, such a situation is known as “safek psik reisha”

in Rabbinic parlance, as the air temperature inside the refrigerator is not

known to the opener.) Contrary to R. Broyde’s assertions, Rav Simcha Zelig’s

language here is a clear proof that Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva was in reference to the refrigerator motor and not the

light.

misreading/mistranslation of Rav Simcha Zelig’s words, as noted above. That Rav

Simcha Zelig added the qualification of “IF IT IS” a psik reisha renders R. Broyde’s words here to be entirely

irrelevant and incorrect. Rav Simcha Zelig’s language of “IF IT IS” a psik

reisha makes clear that he is assuming that the motor is not always

ignited by opening the door, but at times it might be ignited in a manner of psik

reisha, due to the heightened initial air temperature inside the

refrigerator. (Again, such a situation is known as “safek psik reisha”

in Rabbinic parlance, as the air temperature inside the refrigerator is not

known to the opener.) Contrary to R. Broyde’s assertions, Rav Simcha Zelig’s

language here is a clear proof that Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva was in reference to the refrigerator motor and not the

light.

“Professor Sara Reguer noted by email to me that “my grandfather conferred

with scientists and specialists in electricity before giving his response,” and

given this fact it is extremely unlikely that he missed such a basic point that

anyone who repeatedly opened and closed a refrigerator would have noticed.”

with scientists and specialists in electricity before giving his response,” and

given this fact it is extremely unlikely that he missed such a basic point that

anyone who repeatedly opened and closed a refrigerator would have noticed.”

This argument is also incorrect, and is again predicated on R. Broyde’s

mistranslation of Rav Simcha Zelig’s words. Also significant is R. Broyde’s

citation of Dr. Reguer (in his footnote 8) that “she is certain that this teshuva

is referring to the thermostat or motor and not the light.”

mistranslation of Rav Simcha Zelig’s words. Also significant is R. Broyde’s

citation of Dr. Reguer (in his footnote 8) that “she is certain that this teshuva

is referring to the thermostat or motor and not the light.”

“First, the other substantive halachic logic employed by Dayan Rieger which

analogizes elektri to sparks seems to me to be a closer analogy to a light than

to a motor which is hardly fire at all; sparks like incandescent lights, are

fire according to halacha.”

analogizes elektri to sparks seems to me to be a closer analogy to a light than

to a motor which is hardly fire at all; sparks like incandescent lights, are

fire according to halacha.”

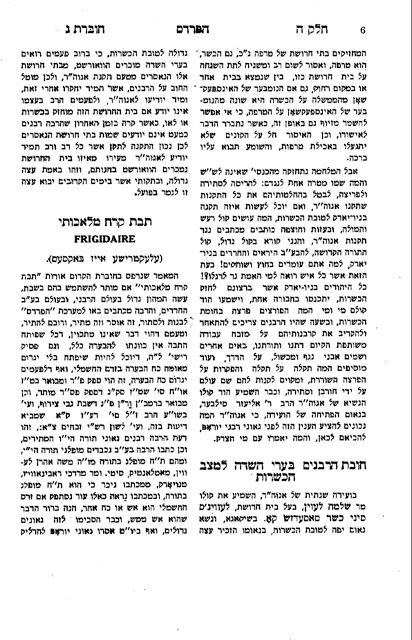

R. Broyde is wrong again. In fact, several poskim have noted that

ignition of the refrigerator motor also generates sparks.[10] See

the words of Rav Chaim Bick[11],

describing the problem of the refrigerator motor in Hamesila (2:1)[12]:

ignition of the refrigerator motor also generates sparks.[10] See

the words of Rav Chaim Bick[11],

describing the problem of the refrigerator motor in Hamesila (2:1)[12]:

וע”י הגלגל

נושב רוח ומוליד הקר לחלק השני של התבה, אשר שמה נמצאים כל צרכי אכל ומשקה. הגלגל

בשעה שמתחיל מרוצתו יוצא ממנו נצוץ-אשי…

נושב רוח ומוליד הקר לחלק השני של התבה, אשר שמה נמצאים כל צרכי אכל ומשקה. הגלגל

בשעה שמתחיל מרוצתו יוצא ממנו נצוץ-אשי…

And by way of the wheel,

the wind (i.e. air) blows and creates the cold in the other section of the box

(refrigerator), where all the food and drink are located. The wheel, when it

begins to run, emits fire-sparks…

the wind (i.e. air) blows and creates the cold in the other section of the box

(refrigerator), where all the food and drink are located. The wheel, when it

begins to run, emits fire-sparks…

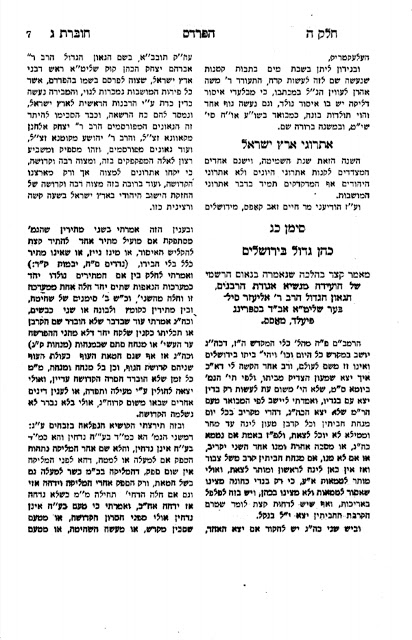

See also the words of Rav Chaim Dovid Regensburg,

describing the problem of the refrigerator motor, in Mishmeret Chaim, siman

3[13]:

describing the problem of the refrigerator motor, in Mishmeret Chaim, siman

3[13]:

ומה שלפעמים ניצוצות ניתזים, ברגע של מגע החוטים

החשמליים אחד בשני, אין זו הבערה, כי מלאכת מבעיר ביחס לשבת לא חשובה אלא אם האש

נאחזת באיזה דבר, וכן כתב הפרי מגדים סי תקב…

החשמליים אחד בשני, אין זו הבערה, כי מלאכת מבעיר ביחס לשבת לא חשובה אלא אם האש

נאחזת באיזה דבר, וכן כתב הפרי מגדים סי תקב…

And that sometimes sparks

fly off,

at the moment that the electrical wires touch each other, this is not havara,

because melechet havara with respect to Shabbat is only considered when

the fire takes hold to something, and so wrote the Pri Megadim…

fly off,

at the moment that the electrical wires touch each other, this is not havara,

because melechet havara with respect to Shabbat is only considered when

the fire takes hold to something, and so wrote the Pri Megadim…

See also the words of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, within a discussion of

the ignition of the refrigerator motor in Minchat Shlomo (Kama), Siman

10, Anaf 2 Ot 4[14]:

the ignition of the refrigerator motor in Minchat Shlomo (Kama), Siman

10, Anaf 2 Ot 4[14]:

אולם יש טוענים

דיש לחשוש לזה, שבכל פעם שמתחדש מעגל חשמלי יוצא במקום החבור ניצוץ קטן של אש

ונמצא שבפתיחתו הוא גורם למלאכת מבעיר…

דיש לחשוש לזה, שבכל פעם שמתחדש מעגל חשמלי יוצא במקום החבור ניצוץ קטן של אש

ונמצא שבפתיחתו הוא גורם למלאכת מבעיר…

However, some claim that one should be careful

about this, that every time that an electric circuit is completes, a small

spark of fire comes out of the place of connection, and thus through his

opening [of the refrigerator door] he is causing the melacha of mav’ir…

about this, that every time that an electric circuit is completes, a small

spark of fire comes out of the place of connection, and thus through his

opening [of the refrigerator door] he is causing the melacha of mav’ir…

Thus, contrary to R. Broyde’s assertion, Rav Simcha Zelig’s mention of

sparks is in fact directly analogous to the ignition of the refrigerator motor,

which actually involved creation of sparks.[15]

sparks is in fact directly analogous to the ignition of the refrigerator motor,

which actually involved creation of sparks.[15]

“Secondly, there has been a regular subset of poskim (as shown by Rabbi

Abadi’s most recent teshuva, Ohr Yitzchak 2:166) who adopt the exact analysis

and view of Dayan Rieger and view the light as lo ichpat since one does

not want it and a light is on already.”

Abadi’s most recent teshuva, Ohr Yitzchak 2:166) who adopt the exact analysis

and view of Dayan Rieger and view the light as lo ichpat since one does

not want it and a light is on already.”

To refer to a single teshuva, published in the 21st

century by a lone posek, as “a regular subset of poskim” would seem to

be somewhat of an exaggeration.

century by a lone posek, as “a regular subset of poskim” would seem to

be somewhat of an exaggeration.

“On the other hand, there is a good and natural impulse to read halachic

literature conservatively and to press for interpretations that align gedolim

with one another and not leave outliers with halachic novelty.”

literature conservatively and to press for interpretations that align gedolim

with one another and not leave outliers with halachic novelty.”

My original note and my comments here in no way reflect any impulse to read

halachic literature conservatively. They reflect my impulse to read halachic

literature correctly.

halachic literature conservatively. They reflect my impulse to read halachic

literature correctly.

“Furthermore, I do recognize that many halachic authorities who have cited

Dayan Rieger’s teshuva have quoted it in the context of the motor and not the

light…”

Dayan Rieger’s teshuva have quoted it in the context of the motor and not the

light…”

More accurately, all halachic authorities who have cited Rav Simcha

Zelig’s teshuva have quoted it in the

context of the motor and not the light.

Zelig’s teshuva have quoted it in the

context of the motor and not the light.

“But, I think these citations are less than dispositive for the following

important reason: Those who quote Dayan Rieger’s view as something to consider

about the motor note that his analysis is halachically wrong…Poskim generally

spend less time and ink explicating the views of authorities whom they believe

to have reached inapt or incorrect conclusions of fact or law compared with

those whom they cite in whole or in part to bolster their own analysis.”

important reason: Those who quote Dayan Rieger’s view as something to consider

about the motor note that his analysis is halachically wrong…Poskim generally

spend less time and ink explicating the views of authorities whom they believe

to have reached inapt or incorrect conclusions of fact or law compared with

those whom they cite in whole or in part to bolster their own analysis.”

It is unclear to me whether R. Broyde means that all of these Poskim

have misunderstood Rav Simcha Zelig’s position, or that they have

misrepresented it. Either way, the assertion is bizarre. I will leave it to the

readers to judge whether such an assertion is tenable.

have misunderstood Rav Simcha Zelig’s position, or that they have

misrepresented it. Either way, the assertion is bizarre. I will leave it to the

readers to judge whether such an assertion is tenable.

The following is a partial list of Poskim and scholars who have

cited Rav Simcha Zelig as having permitted opening a refrigerator on Shabbat

when the motor will go on, and not

in the context of the refrigerator light[16]:

cited Rav Simcha Zelig as having permitted opening a refrigerator on Shabbat

when the motor will go on, and not

in the context of the refrigerator light[16]:

1)

Rav Ovadya

Yosef (Yabia Omer, Orach Chaim Chelek 1, Siman 21, Ot 7)

Rav Ovadya

Yosef (Yabia Omer, Orach Chaim Chelek 1, Siman 21, Ot 7)

2) Rav Yehoshua

Neuwirth (Shemirat Shabbat Kehilchata, Perek 10 Footnote 33 in

the 1979 edition. This appears in Footnote 37 in the 2010 edition.)

Neuwirth (Shemirat Shabbat Kehilchata, Perek 10 Footnote 33 in

the 1979 edition. This appears in Footnote 37 in the 2010 edition.)

3)

Rav J. David

Bleich (Tradition, Spring 2017, pages

57-58)[17]

Rav J. David

Bleich (Tradition, Spring 2017, pages

57-58)[17]

4)

Rav Chaim

Bick (Hamesila 2:1)[18]

Rav Chaim

Bick (Hamesila 2:1)[18]

5)

Rav Gedalia

Felder (Yesodei Yesurun, vol. 3 page 293)[19]

Rav Gedalia

Felder (Yesodei Yesurun, vol. 3 page 293)[19]

6)

Rav Shlomo

Tanavizki (Birkat Shlomo, end of siman 2)[20]

Rav Shlomo

Tanavizki (Birkat Shlomo, end of siman 2)[20]

7)

Rav Moshe

Shternbuch (Teshuvot Vehanhagot vol. 1 Siman 220)[21]

Rav Moshe

Shternbuch (Teshuvot Vehanhagot vol. 1 Siman 220)[21]

8)

Rav Chaim

Fishel Epstein (Teshuva Shleima vol. 2, end of Siman 6)[22]

Rav Chaim

Fishel Epstein (Teshuva Shleima vol. 2, end of Siman 6)[22]

9)

Rav Chaim

Dovid Regensburg (Mishmeret Chaim, Siman 3, page 27) [23]

Rav Chaim

Dovid Regensburg (Mishmeret Chaim, Siman 3, page 27) [23]

10)

Rav Chaim

Druck (Noam Vol. 1 page 281)[24]

Rav Chaim

Druck (Noam Vol. 1 page 281)[24]

11)

Rav Shmuel

Aharon Yudelevitz (Hachashmal Leor Hahalacha, page 130)[25]

Rav Shmuel

Aharon Yudelevitz (Hachashmal Leor Hahalacha, page 130)[25]

12)

Rav Yosef

Schwartzman (Shaashuei Torah, Chelek 3 – Shabbat, pages 391-392)

Rav Yosef

Schwartzman (Shaashuei Torah, Chelek 3 – Shabbat, pages 391-392)

13)

Rav Shlomo

Pick (Who is Halakhic Man?, in Review of Rabbinic Judaism 12:2, page

260)[26]

Rav Shlomo

Pick (Who is Halakhic Man?, in Review of Rabbinic Judaism 12:2, page

260)[26]

In conclusion, it is clear that Rav Simcha Zelig’s teshuva about

opening refrigerators on Shabbat addressed the problem of the motor turning on

when the door is opened. Every argument put forth by R. Broyde is wrong. Rav

Simcha Zelig’s position was that it is permitted to open a refrigerator when

the motor will go on, as triggering the motor is classified as a psik

reisha d’lo ichpat lei, which is equivalent to lo nicha lei. Rav

Simcha Zelig never addressed opening a refrigerator when the light will

go on.

opening refrigerators on Shabbat addressed the problem of the motor turning on

when the door is opened. Every argument put forth by R. Broyde is wrong. Rav

Simcha Zelig’s position was that it is permitted to open a refrigerator when

the motor will go on, as triggering the motor is classified as a psik

reisha d’lo ichpat lei, which is equivalent to lo nicha lei. Rav

Simcha Zelig never addressed opening a refrigerator when the light will

go on.

Postscript:

Regarding R. Broyde’s admonition of my tone, that “we certainly could use

more light and less heat”, I could not disagree more. I will simply quote the

words of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveichik in his remarkable speech at the 1956 Chinuch

Atzmai Dinner, in appreciation of Rav Aharon Kotler[27]:

more light and less heat”, I could not disagree more. I will simply quote the

words of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveichik in his remarkable speech at the 1956 Chinuch

Atzmai Dinner, in appreciation of Rav Aharon Kotler[27]:

קאלטע תורה, ווי

קאלטע ליכט, איז גארנישט. עס דארף זיין הייס ליכט, א’מיר’זך

אפ’בריען ווען מ’קומט’מן צו אים…

קאלטע ליכט, איז גארנישט. עס דארף זיין הייס ליכט, א’מיר’זך

אפ’בריען ווען מ’קומט’מן צו אים…

Cold Torah, like cold light, is worthless. It must

be heated light so that one burns himself in its proximity…

be heated light so that one burns himself in its proximity…

[7] See Rav J. David Bleich’s typically thorough

treatment of the topic of refrigerators in Tradition

(Spring 2017, pages 57-59 and 64-65) for a discussion of why triggering the

refrigerator motor would be considered lo

nicha lei.

treatment of the topic of refrigerators in Tradition

(Spring 2017, pages 57-59 and 64-65) for a discussion of why triggering the

refrigerator motor would be considered lo

nicha lei.

[10] Rav J. David Bleich in Tradition (Spring 2017, page 72) has noted that while a number of

earlier poskim dealt with the issue

of sparking in refrigerators, sparking has now been eliminated in most

modern-day appliances.

earlier poskim dealt with the issue

of sparking in refrigerators, sparking has now been eliminated in most

modern-day appliances.

[11] For biographical information on Rav Chaim Bick, see

here.

here.

[15] While Rav Regensburg assumed that the creation of

sparks would happen only sometimes, it appears that Rav Bick and Rav Shlomo

Zalman assumed that the creation of sparks happened every time the motor was

triggered, and thus would be included in the category of safek psik reisha.

sparks would happen only sometimes, it appears that Rav Bick and Rav Shlomo

Zalman assumed that the creation of sparks happened every time the motor was

triggered, and thus would be included in the category of safek psik reisha.

[16] My thanks to Dr. Marc Shapiro for bringing to my

attention the references to Rav Felder, Rav Shternbuch, Rav Druck and Rav

Schwartzman.

attention the references to Rav Felder, Rav Shternbuch, Rav Druck and Rav

Schwartzman.

[17] My thanks to Rabbi Yitzchok Segal for bringing this

reference to my attention.

reference to my attention.

[27] Watch here at approximately 28:00. See also Making of a

Gadol, Second Edition, page 1019, for specific examples of Rav Aharon Kotler’s

heated remarks in defense of his Torah positions.

Gadol, Second Edition, page 1019, for specific examples of Rav Aharon Kotler’s

heated remarks in defense of his Torah positions.

One thought on “A Final Note Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator on Shabbat”

A small anecdote regarding the meaning of the word "elektri" – as a talmid of Rav Gustman zt"l I recall seeing a check that the Rosh Yeshiva made out to the "chevrat hachashmal" where he substituted "chashmal" for "elektri" – i.e. the check was made out to "chevrat haelektri" – as he felt that the word "chashmal" in lashon hakodesh and used by the navi Yechezkel means something completely different.

It is obvious that in yiddish, elektri referred to electricity in general.