The Valmadonna Broadside Collection: Review essay

By Eliezer Brodt and Dan Rabinowitz

The Writing on the Wall: A catalogue of Judaica Broadsides from the Valmadonna Trust Library, edited by Sharon Liberman Mintz, Shaul Seidler-Feller and David Wachtel, London-New York: 2015, 320 pp.

Jews have been collecting books or manuscripts for centuries. A related category that is collected by fewer is ephemera, including broadsides, documents and letters of historical significance. Of late, a few annual auctions have included some of these documents among the other objects to be auctioned. Sadly, after their appearance in the auctions’ catalogs, most of the rare items disappear in to private collections and are invariably almost impossible to track down post-auction. The result is that a valuable amount of historical information is lost to the public. Moreover, to date, there is no database that tracks or records these items.[1]

First, a definition of the type of material – broadsides; they “are all around us whether we recognize them as such or not. Walking down the street… entering the lobby of a public building… we daily even hourly see flyers for event, advertising posters, public announcements and more.” Using “the most expansive conception we can say that the broadside has been with us since antiquity… The public display of information… has been ubiquitous for a very long time.” (p. 6).

In an important and excellent essay on Jewish bibliography written in 1976,[2] Professor Israel Ta-Shema remarks that because broadsides were intended and read by “thousands and potentially hundreds of thousands” they are among the “important sources for both Jewish history and the history of Hebrew printing.”

ענין לעצמו שלא זכה למיטב ידיעתי לשום טיפול עד עצם היום הזה, הוא רישומם הביבליוגרפי של ‘הדפים הבודדים’. לפי הערכות שקולות מגיע מספרם של אלה לאלפים רבים, ואולי עד כדי רבבה, וחשיבותן הן לידיעת תולדות ישראל והן לידיעת קורות הדפוס העברי גדולה ביותר. בדרך כלל קשורים דפים אלה במריבות בין חשובי הקהל ורבניהם, סכסוכי משפחות, בנים נודדים, פולמסים דתיים וכו’. דפים אלה שנתלו או הודבקו על קירות בתי הגיטו או בבתי הכנסת וכד’ אבדו ברובם המכריע, וכל מה שנשתמר מהם הוא בגדר יוצא מן הכלל. ערך ביוחד יש לסוג ספרותי זה ביחס לפולמוסים הפנים-חסידיים והמתגנגדיים. לסוג זה יש לצרף את המודעות והכרזות עד לתקופתנו אנו, כולל כרוזי המחתרות האנטי היטלריסיות בחו”ל והאנטי מנדטריות בארץ ישראל, כרוזי נטורי קרתא וכד’, שהם רבים מאוד. מלבדם נדפסו על דפים בודדים, קמיעות וסגולות, לוחות קיר, דברי פרסומת, הסכמות נפרדות ועוד, ויש ביניהם גם מעשיות עממיות קצרות על דף אחד. [מצוי ורצוי בביבליוגרפיה העברית, יד לקורא טו (תשל”ו), עמ’ 79-7 ].

History is not the only subject to benefit from broadsides. The prolific author, R. Eliyahu David Teomim (Aderet), published and annotated a broadside recording the customs of the Great Synagogue of the Austria, whose Rabbis had included R. Shmuel Edels (Maharsha).[3]

Recently some of collectors of broadsides have begun printing and reproducing these priceless treasures.[4] The Valmadonna Trust Library (see

here), still one of the most significant private Hebraica libraries (for an appreciation of the Valmadonna Library, penned by its librarian and published at the Seforim blog in 2009, see

here), published a catalog of the broadsides in its collection,

The Writing on the Wall: A catalogue of Judaica Broadsides from the Valmadonna Trust Library, edited by Sharon Liberman Mintz, Shaul Seidler-Feller and David Wachtel (see

here). In conjunction with the publication of the catalog, the Trust also made available online (

here) all of the documents in its collection for further study. The collection is comprised of broadsides from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries and incorporates items from Italy (the library generally focused on Italy and Italian items and broadsides are no exception, with Italian broadsides being the largest of the collection), and elsewhere in Europe, Israel, Yemen, Iraq, Constantinople, India, and even one from America.

The book consists of a few parts. It begins with five scholarly essays on specific subjects by various experts. Following are excellent full-page reproductions of thirty-six highlights from the collection, including a description explaining the significance of the specific document. A full catalog of the collection is included and is divided into six main categories; each category is chronologically ordered. The six categories are: Poems, Prayers, Documents from Within the Jewish Community, Documents from Outside the Jewish Community, Calendars and Education. Each entry includes a description of the item, the title, author place and date of printing, printer, size and language. Some entries include additional bibliographical sources; others provide a small image of the item. Additionally, the non-English broadsides included in the highlight section are translated. The volume concludes with various other useful indexes.

The first introductory essay is an excellent overview of Jewish broadsides by Adam Shear. Shear asks and answers the basic questions that come to mind, such as: “What was the purpose?”, “Who was the audience?”, “Where were they displayed?” and the like, none of which can be answered singularly.

The second essay is by Elisheva Carlebach and focuses on the Jewish wall calendars in the collection.[5] She explores what can be learned from tracing the cultural history of one of the printers of these calendars through various calendars he printed. Some of these calendars were very sophisticated and it’s unclear who the targeted audience was. Emphasizing calendar broadsides’ unique value, she concludes that “the most ephemeral of forms, broadside calendars preserve a glimpse of the printshop as workspace, the spirit of entrepreneurship and the enduring values of the creators of these humble yet precious objects” (p. 30).

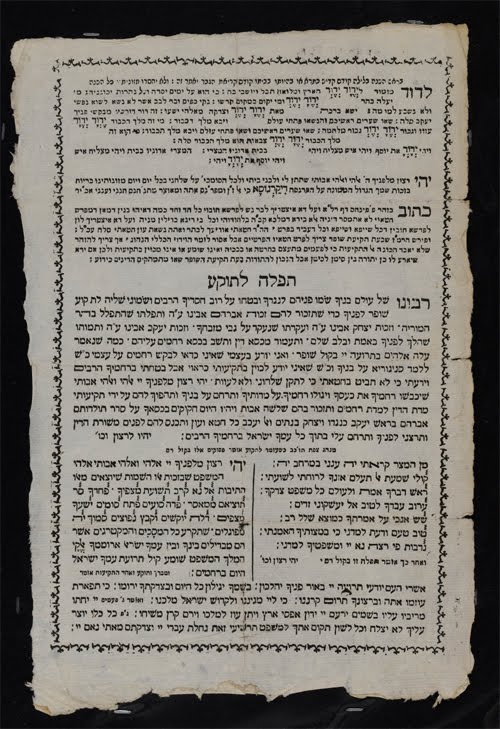

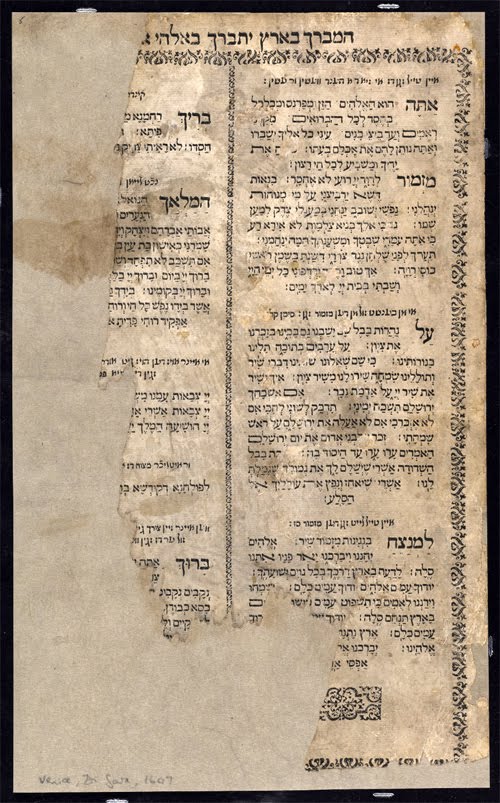

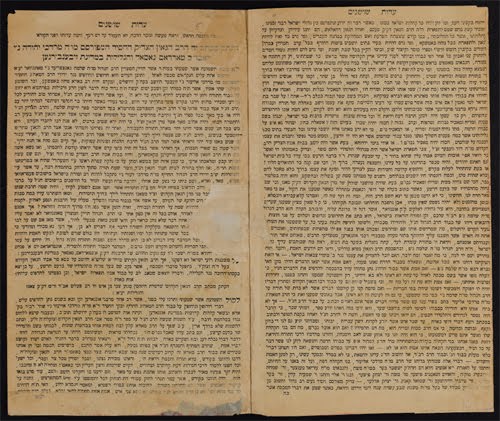

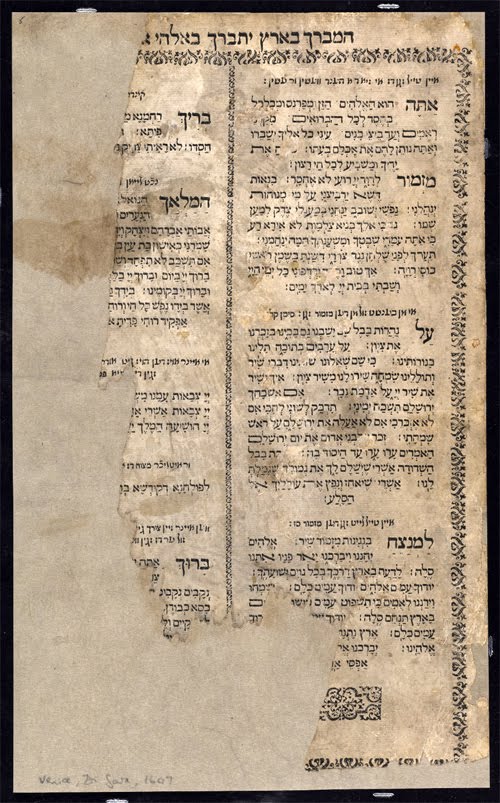

The third essay is written by Ruth Langer and focuses on the Liturgical Broadsides of the collection. Some are prayers for current events, one of interest (printed on p.33) is for a memorial service for a building that collapsed in Mantua in 1776 where three weddings were taking place simultaneously.[6] Also discussed are the prayers for various civic events (p. 35) and for the various governing powers, a subject which still needs to be explored in depth. Some of these broadsides were clearly displayed in shuls; one includes the language of the prayers, defusing the power of bad dreams and request for substance, that are recited along with Birchat Cohanim (p.15), others include prayer that are recited during Selichot (p.14). One broadside, printed in Izmir in 1890, contains the Vidduy of Yom Kippur, printed with each entry of the Aleph Beis featuring other sins under that letter, very similar to the sheets given out in various shuls today (p.44). Not all were intended for the public display, the following broadside from Venice 1607 (Item # 153) appears to have been hanging in the house, for the owners’ personal use.

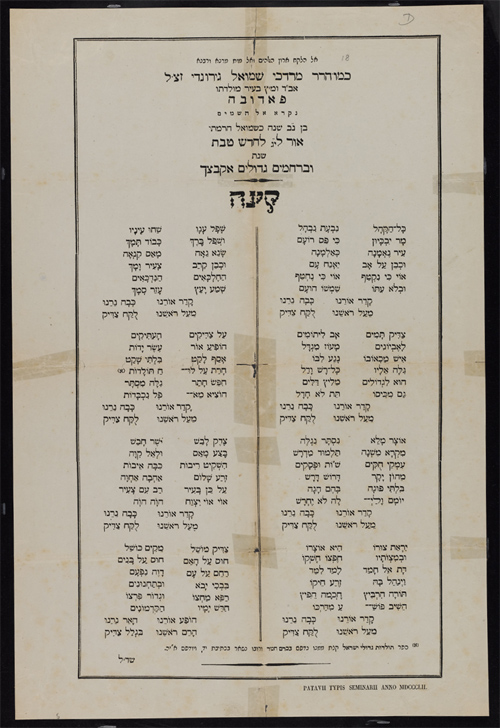

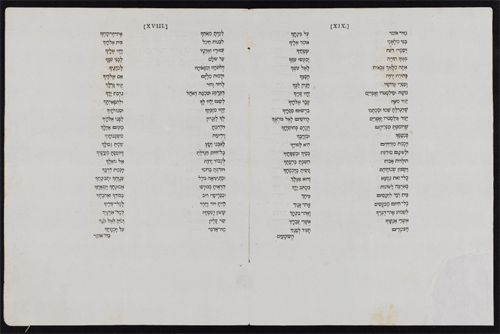

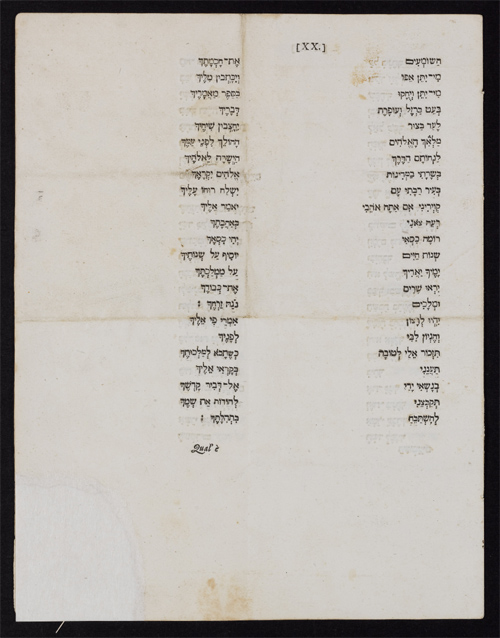

The next essay, by Dvora Bregman, focuses on the Hebrew poems in the collection (mostly from Italy). This section also highlights various pieces of historical interest. Reading through it, one is amazed how poems were written for literally every occasion – completion of Mishna, Venice, 1630 (p.55), receiving a medical degree (p.51, there are sixteen examples in the collection), in honor of R. Israel Chazan’s[7] visit to the old Greek synagogue in Corfu in 1853 (item # 134) (see below). Some of the poems were written after the deaths of prominent people such as an Italian elegy for R’ Moshe Zacuto which is reproduced in full and translated from Italian to English. Other elegies include one for R’ Yehudah Aryeh Modena (see below) and for R’ Mordechai Gerondi, the latter written by his friend Shadal (see below). There are also many “wedding riddles” in the collection – providing evidence of another rich and diverse aspect of Jewish life in Italy.

The next section, originally written in Hebrew by Nachum Rakover and translated into English for this volume by Shaul Seidler-Feller, focuses on the Takanot broadsides found in this collection. Sumptuary edicts, limiting the size of a celebratory affair and the amount of people invited, the amount of food to be served, or the amount of money to be spent on various sorts of occasions were commonplace from the medieval until the modern period. For example, we note that the Nodeh Beyhehudah and his beis din in Prague issued a list of such Takonot.[8] Rakover is in middle of preparing for publication a thorough study on the subject. In the volume under review, his article deals with the seventeen Italian broadsides related to sumptuary laws in the Valmadonna Collection from 1598-1794. The article is impressive in its sweeping review of the topic and the placement of these items within the larger narrative. What is apparent from the examples in the collection is that sumptuary laws have been persistent. Indeed,

recently the cudgel has been taken up anew and a new round of such edicts by numerous rabbis and Hasidic leaders to limit spending has been promulgated.

Exploring the Collection

The introductory essays are only the beginning in what can be uncovered in a collection as rich as this one. By providing online access, the Trust has insured that can occur. To begin that exploration, we discuss a few choice examples.

As was recently the case with American Pharaoh, Jewish have been involved in sport, and specifically horse racing. The collection includes two Italian broadsides discussing the horses and the Jewish sponsorship of a horse race. (Nos. 311 & 328).

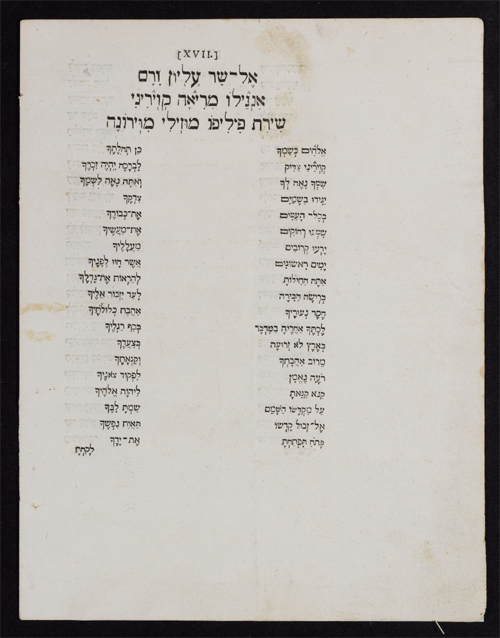

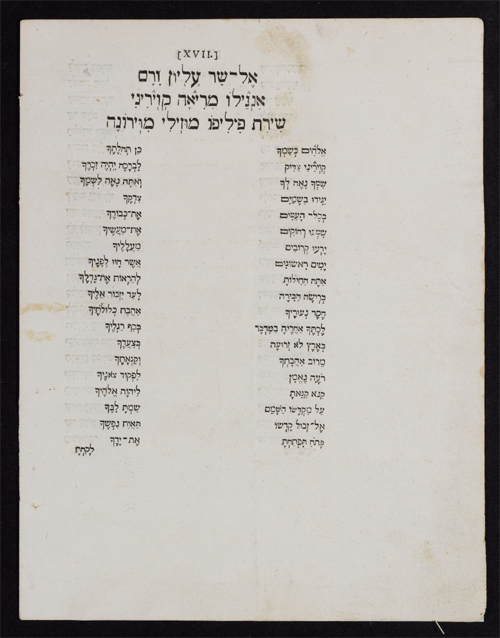

One surprising and lengthy – some ninety lines – ode was composed in Hebrew (ca. 1740) and is a “poem of praise and supplication addressed to Angelo Maria Quirini (1680-1755),

an Italian Cardinal.” This item is “a single bi[-]folio excised from a larger work, most likely a pamphlet,” and is “not a true broadside.” (No. 130). No additional information is provided on this intriguing item.[9]

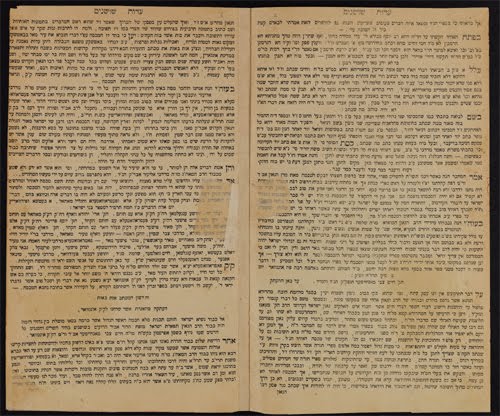

Friday Night Candle Lighting Prayers

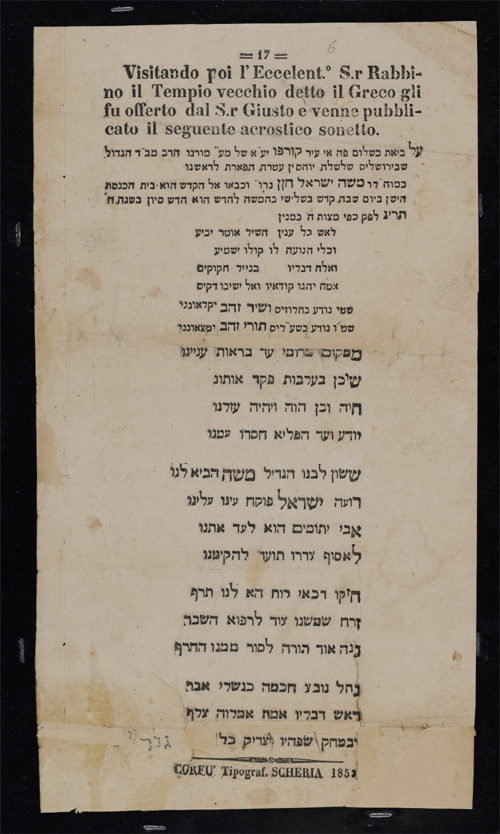

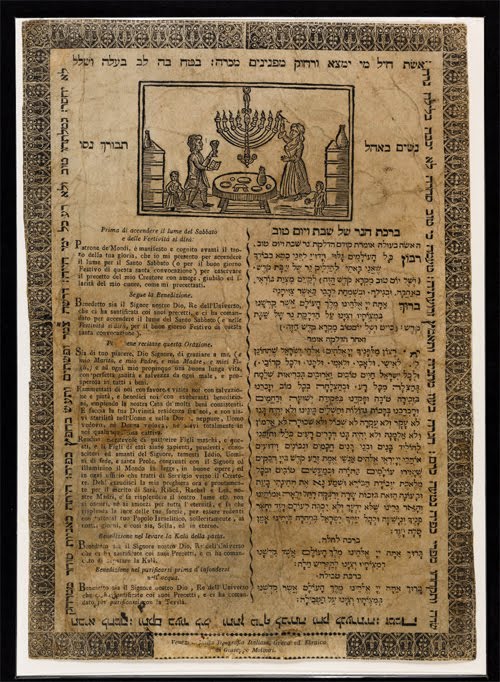

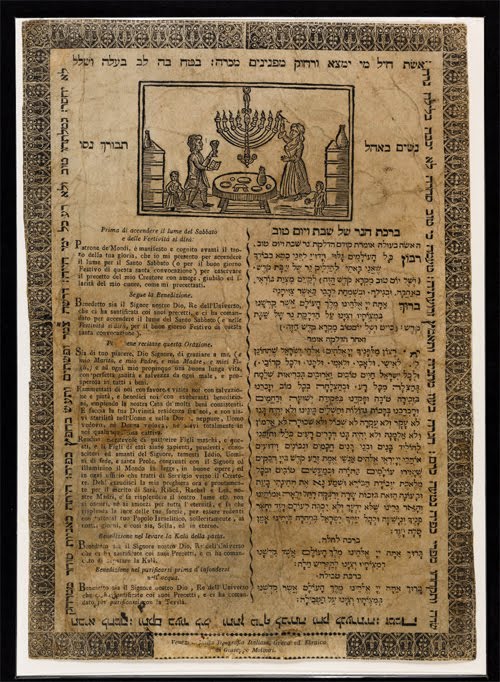

The following broadside from Venice 1835, (reproduced on p. 17), contains the text of the prayers that were customarily recited by women on Friday evening during the candle lighting ceremony.

The illustration depicts a woman lighting eight candles. The Rishonim, including Italian sources, Shibolei Haleket (Siman 59) and Sefer Hatadir (p.196), only require and discuss two candles for Shabbos.[10] The question is when exactly did people start lighting more? The exact time when this began is unknown. However, in the “Shulchan Aruch” from R’ Yehudah Aryeh Modenah (1571-1648) he describes the Italian custom of lighting multiple candles:

והנשים חייבות להדליק בבית נר של שמן ובתוכו לכל הפחות ארבע או שש פתילית להאיר בערב עד עבור חלק גדול מהלילה [עמ’ 54].

Some continued to advance the numbers and in the 19th century, one author records the custom of lighting 31, 45, and 52 candles weekly.

מה מאוד היה מכבד שבת ויום טוב והיה מנהגו להדליק בכל שבת ל”א נרות כמנין אל כי בו שבת אל מכל מלאכתו, ובסוף ימיו מ”ה נרות, ולפני מותו היה מצווה להדליק בשנה ראשונה בחדר שהיה לומד בו נ”ב נרות כל שבת [מה שהעידו על ר’ הירץ אברהם נפתלי שייאר בהקדמת נכד המחבר לפירושו תורי זהב, (על שיר השירים), ירושלים תשס”ג, עמ’ טז].

Corporal Punishment

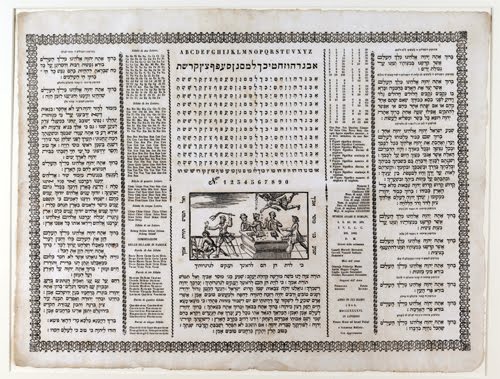

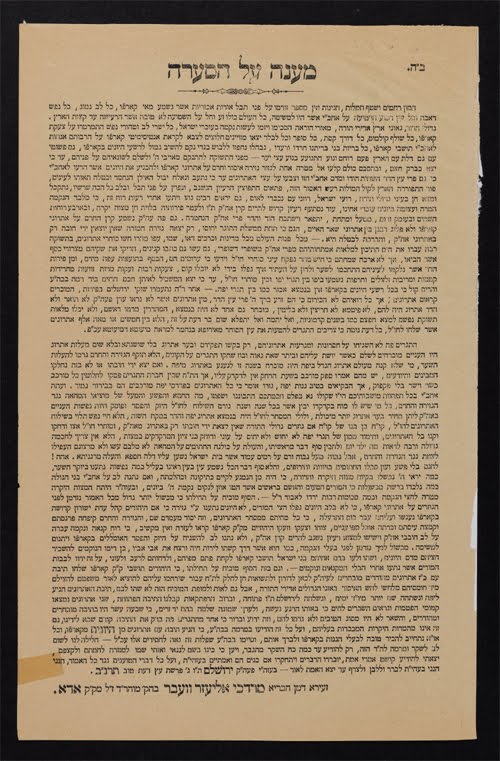

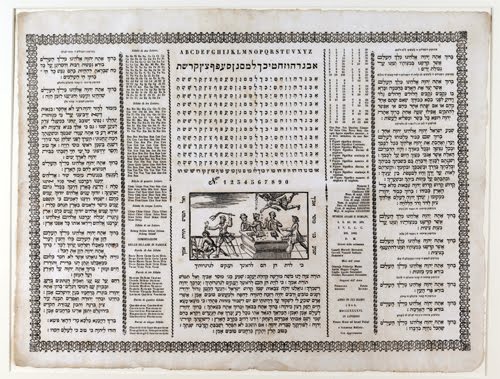

The following broadside poster for the instruction of children is from Italy 1846 (125):[11]

One striking part of the image is of the teacher hitting children in school. This sort of practice is recorded in a number of Jewish texts.[12] For example:

A 17th century autobiography recounts that “the new teacher was of an irritable temper… he hit me and put me to shame…”. [Alexander Marx, Studies in Jewish History and Booklore, New York 1944, p. 193].

R’ Yaakov Emden writes in his autobiography:

בשנות הילדות… אזכיר איזה גרגרים, שלשה דברים נוראים שקרו לי בימי ילדותי הרכות. … ומלבד המכות אשר הוכיתי בית מאהבי המלמדים אשר נמסרתי בידיהם ללימוד, היו על פי רוב אכזרים, היכוני בלי חמלה… [מגלת ספר, עמ’ 84].

Saul Berlin writes in his satirical work:

ומתועלת ההכאה עוד, כי הוא צד היתר למלמדים לקבל שכר, כי על הלמוד לבד אסור לקבל שכר, משום קרדום לחתו בו, ואם כן כל מלמד המרבה להכות הרי זה משובח… ועוד רבה התועלת ע”י ההכאה אשר הילדים מכים ולוקים בבית הספר, כי ליראתם את המכות קרבת מוריהם יחפצו וירבו עליהם מוהר ומתן למען חנות אותם, ובהגיע חודש ומועד יפצירו הילדים באבותם לתת להם משאת רב, להביא אל רבם לתתם לו כופר נפשם…”. [כתב יושר, [בתוך: יהודה פרידלנדר, פרקים בסאטירה העברית בשלהי מאה הי”ח בגרמניה, תל אביב תש”ם], עמ’ 98].

R’ Yosef Kara writes:

שבהיותי בצוותא חדא אם כבוד ידידי הגאון הצדיק מו”ה שמעון סופר אב”ד דק”ק קראקא… והוא אמר ז”ל כי זה רע חולי שאין חפץ לגדולי לומדי תורה להיות מקרי דרדקי, כי הוא חרפה להם ע”כ מוכרחים אבות הבנים ליתן בניהם הקטנים אל איש אשר לא ידע ספר קרוא מקרא ודקדוק אך ידע להכות הבנים ולזעוק בקול גדול… [קול אמר קרא, פ’ פנחס, עמ’ 20].

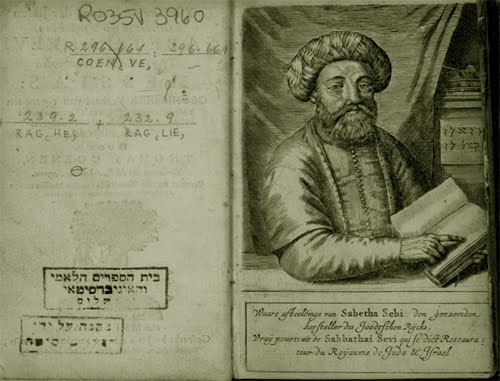

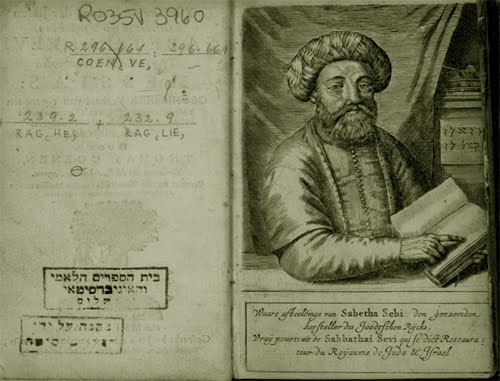

This broadside from Amsterdam 1666 is a little more famous, as it’s a supposed depiction of Shabbetai Tzvi. A complete translation for the Dutch is provided in at the appendix (pp.264-65).

Gershom Scholem writes that this portrait of Tzvi is fictitious – one of a number of imaginary portraits. (

Sabbatai Sevi, pp. 190-191, 158). The only picture of Shabbetai Tzvi believed to be authentic (that is, drawn by a witness) is the one found in the beginning of Thomas Coenen’s book

Ydele Verwachtinge der Joden, Amsterdam 1669.[13] There might be others as well, but King Jan Casimir ordered all pictures of him to be destroyed (

id., p. 597). This one, fortunately, was published.

(This is from Scholem’s personal copy.)

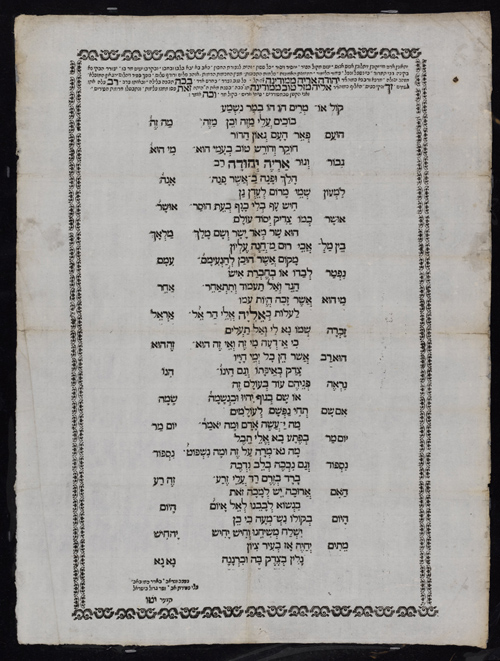

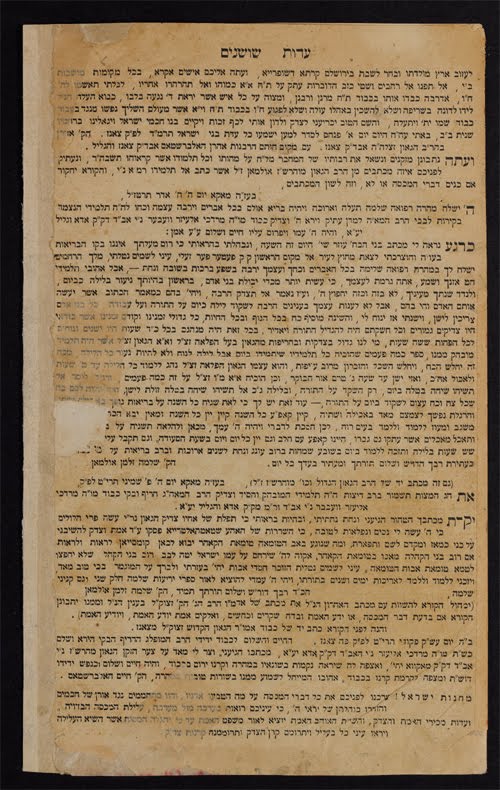

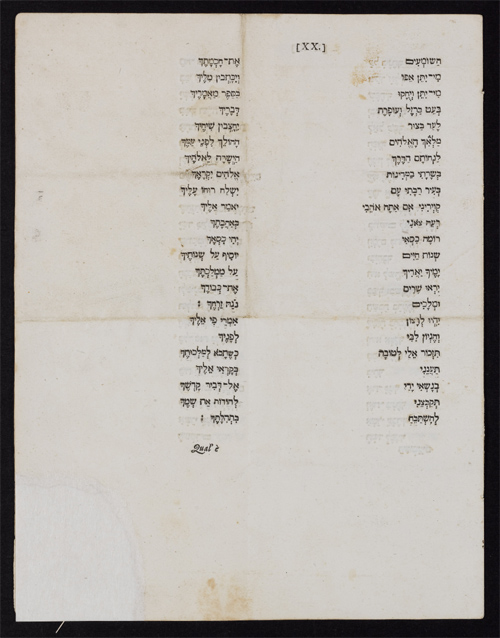

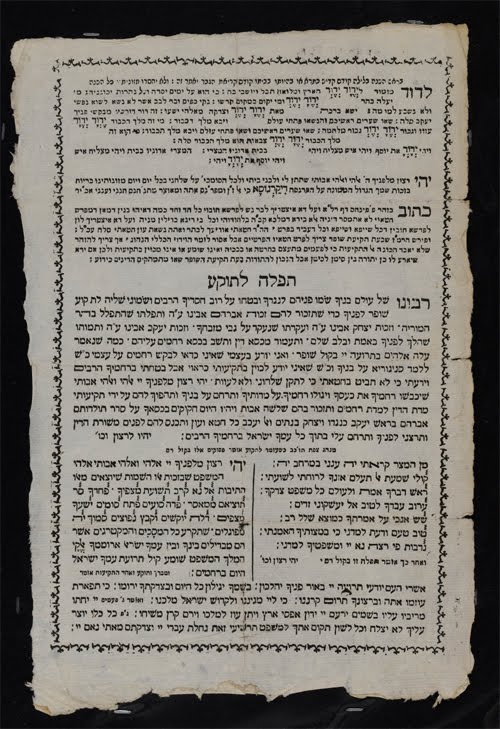

Kabbalistic Tefilos for Rosh Hashanah

This broadside from Mantua 1790, reproduced in the book (p.43), is of interest for several reasons. First, the top part of the broadside has the twenty fourth chapter of Tehilim, said by many Kehilot on Rosh Hashanah as a segulah for Parnasa.[14] In a work written around 1700, recently printed from manuscript, we find the author writes:

אחר ערבית, יש לי תוכחת מגולה ומסותרת אם קצת משכילים, שהנהיגו לקרות בבית הכנסת בציבור אחר עלינו לשבח בלילי ר”ה, מזמור לה’ הארץ ומלואה, ולכוין הנקוד של השם, ככתוב בספר שערי ציון, שהוא מסוגל לפרנסה, שלא יפה הם עושים, כי לא כן צוה הרב המגיד לנו סוד זה, והצנועים נהגו לאמרו בשני הלילות שתי פעמים בכל לילה תכופים זה לזה… והקריאה על שולחנו קודם ברכת מזון… דבר הלמד מענינו, בהצנע לכת עם אלקיך. על כן אמרתי ימים ידברו, להויע ידידי הקורא שדבר בדוק ומנוסה שכל סגולה הנעשית על ידי תפלה בשום כוונה או שם, שאין לך לפרסמו ברבים. ולא לגלותו כי אם לתלמיד הגון ירא חטא ובלחישה, לבל היה מוליך רכיל מגלה סוד, שאז תהיה הפעולה חלושה… [ר’ כליפא בן מלכה, כף נקי, [לוד תשע”ד] עמ’ 167].

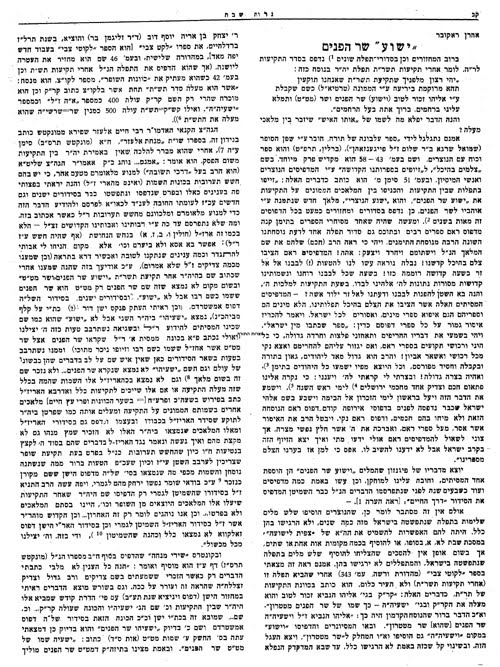

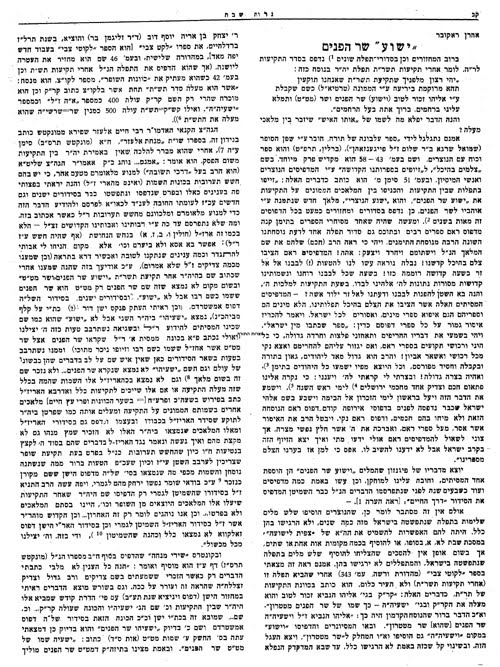

The second part of this broadside is also of interest, as it has the tefilos said before, during and after the shofar blowing, including some of the Kabblastic tefilos with names of angels. Of note is what is omitted here, those parts said between the various sets of Shofar blowing, which has been the subject of lots of literature[15], as it includes a very strange phrase, that seemingly evokes Jesus: ישוע שר הפנים””.

Here is an article written on this topic by R’ Shmuel Ashkenazi written in 1944 (!) under one of his pen names:

One more point related to this topic is a case of censorship. R’ Chaim Kraus writes:

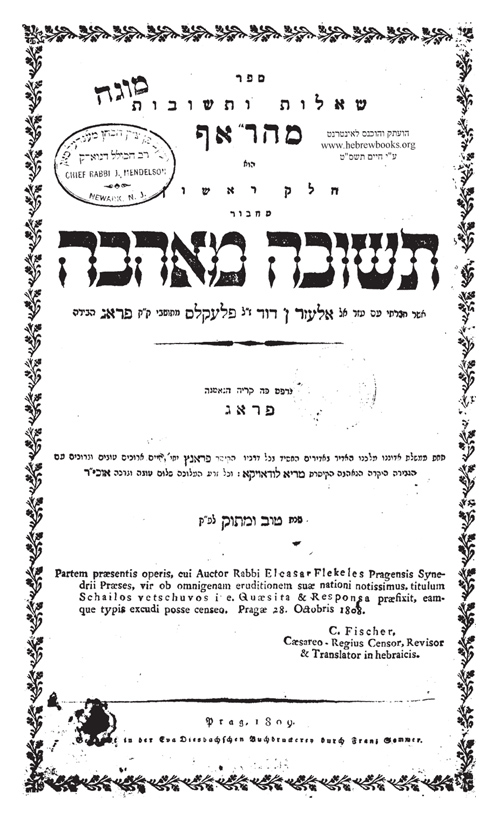

הנה בזכר יהוסף… מתיחס לזה שבדפוסים האחרונים בשו”ת תשובה מאהבה הושמט הענין הנ”ל שכתב בחריפות נגד אמירת היהי רצון שמות המלאכים… [מכלכל חיים בחסד, עמ’ סד].

However, upon checking the sources to see when in the printing of the sefer Teshuvah M’Ahavah this censorship took place, one is hard pressed to find it, as it’s simply not there. The actual issue is a bit different; Kraus misunderstood R’ Yosef Zechariah Stern’s teshuvah.

In an extraordinary teshuvah dealing with these prayers (Zecher Yehosef, Siman 210), R’ Yosef Zechariah Stern mentions a certain case of censorship:

ובתשובה מאהבה ח”א סי’ א שהועתקה תשובתו בדבר הפיוטים ברוב המחזורים.. והמדפיסים להפיס דעת ההמון שהורגלו באמירת היהי רצון שבתקיעות השמיטו מה שהזכיר בסוף התשובה אות ס’ שמרעם בהזכרת שמות המלאכים… וכן השמיטו המדפיסים בהעתקתם מהתשובה מאהבה מה שהעיד מהנודע ביהודה שאחד היה רוצה לברך על אתרוג המהודר שלו וכשראה שאומר היהיה רצון… אמר איני מניחו לברך על אתרוג שלי…

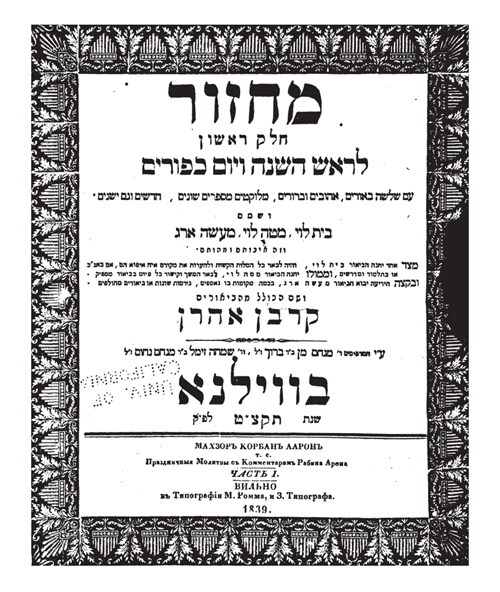

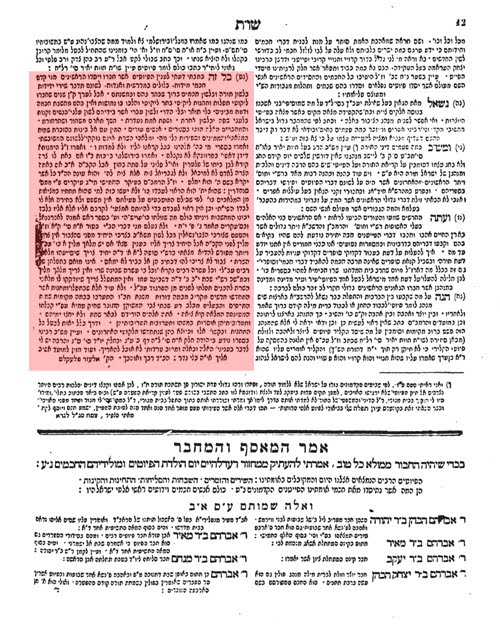

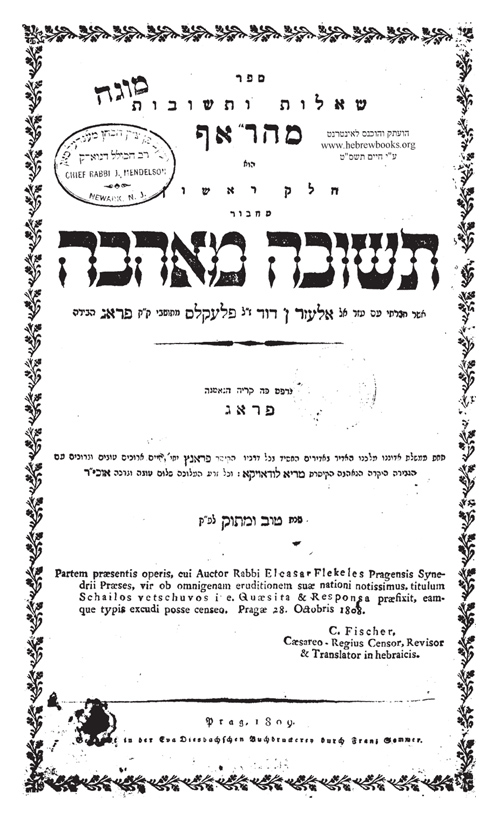

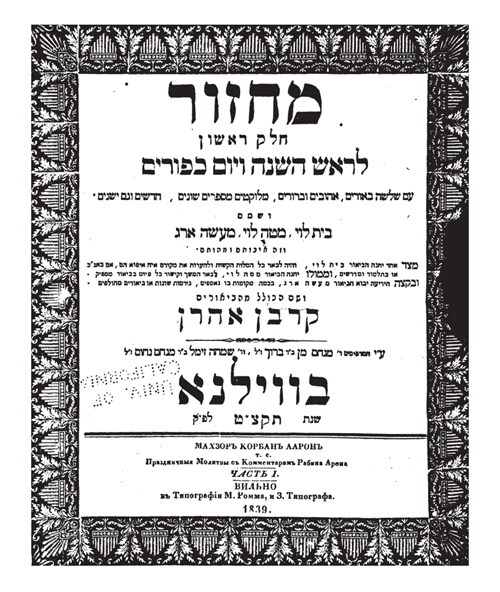

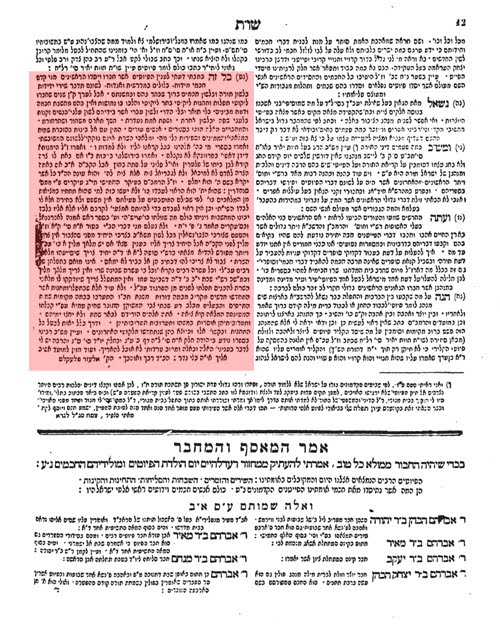

This Teshuvah was printed in various Machzorim at the time and that is where these parts of the teshuva were indeed bowdlerized. See the following images for the pages as they appear in the

Korbon Aharon Machazor printed in Vilna in 1839 and compare with the first print of the teshuvah (Prague, 1809).

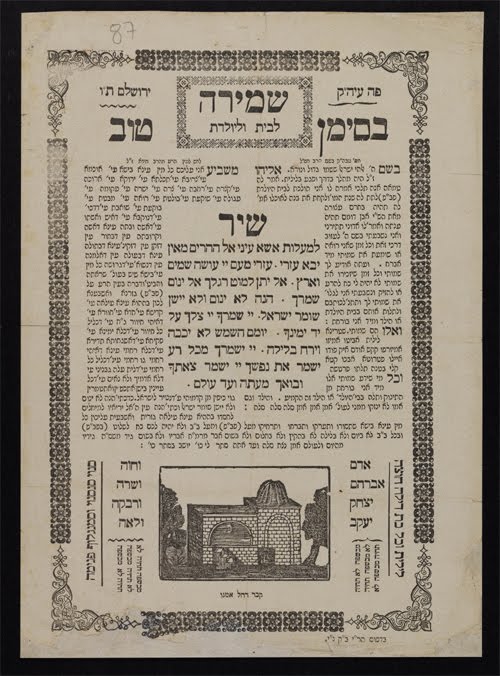

Amulet Broadsides

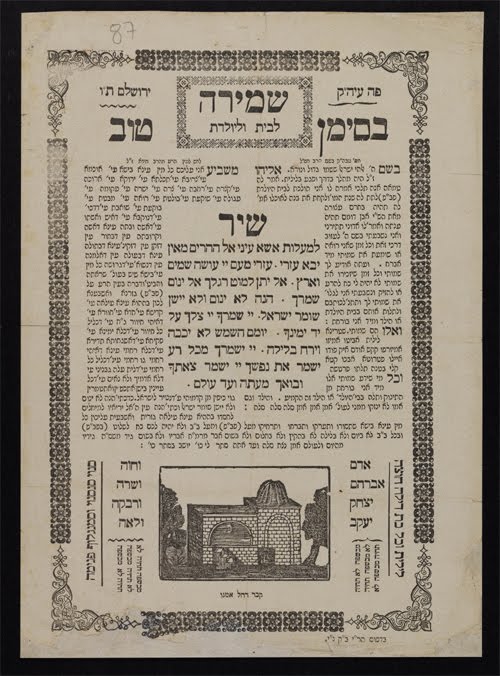

This image from Jerusalem 1870 (pp. 130-131) highlights another notable part of this collection – the Amulet section. It contains numerous broadsides against the “evil eye”, aimed at protecting the newborn mother from Lilith and the like (pp. 132-135, 141-143, 194-197). This is yet an additional set of documents which demonstrate how widespread it was for people to use amulets and the fear of the “evil eye” and the like.

There are numerous sources on regarding amulets, some mentioned

here.[16] One source, that was only recently published in English, is from a fascinating memoir by Pauline Wengeroff, who writes: “for the same purpose of protecting the newborn, Jews used to affix kabbalistic prayers called

shemaus over the head of the new mother, a second page on the door and a third between the cushion of the child.”[17]

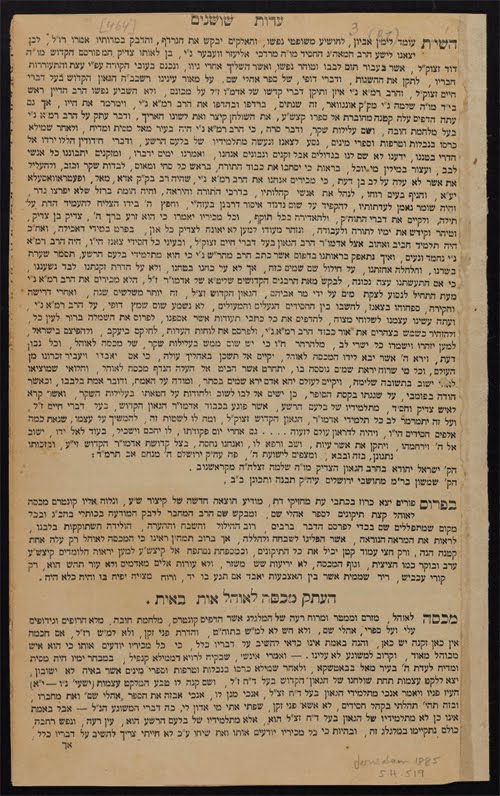

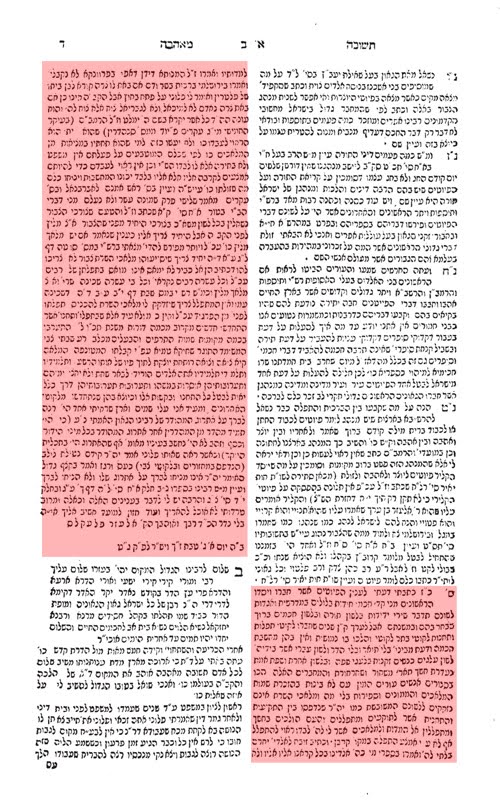

Controversy against R’ Shlomo Ganzfried – Author of Kitzur Shulhan Aruch

This document relates to a controversy between R’ Shlomo Ganzfried and the R’ Chaim Halberstamm, the Divrei Chaim. In his work Ohali Shem on Gittin, R’ Ganzfried took issue with some legal rulings of the Divrei Chaim. This erupted into a series of small works from R’ Weber, starting in 1882, defending the honor of the Divrei Chaim. R’ Ganzfried responded to one of them in the back of the 1884 edition of his Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.

This broadside (above) from R’ Weber against R’ Ganzfried, found in the Valmadonna Collection, is very rare (p. 217 #360).[18]

The Valmadonna Collection has another rare broadside from R’ Weber (below), related to the famous controversy of the Corfu Esrogim (p. 219 # 369).[19] This is not included in Naftali Ben Menachem’s otherwise comprehensive article regarding R’ Weber.

Regarding this broadside, it’s worth quoting the great historian[20] and native of the Old Yishuv, Eliezer Malachi:

ור’ מרדכי אליעזר וובר, הרב דאדא, זה האחרון היה אש לוהטת, ובקנאותו לא ידע גבול, עד שבשנת תרנ”א אסרו את אתרוגי קורפו לטובת אתרוגי ארץ ישראל, נלחם הוא להתיר אתרוגי קורפו ולאסור את אתרוגי ארץ ישראל שגדלים בפרדסי המושבות של חובבי ציון [מנגד תראה, עמ’ 225].

The volume is beautifully produced, the reproductions are excellent, and is available in a larger format “coffee table” size. This is a great volume, for collectors of books and history. It is available for purchase

here and at the YU Seforim sale

here.

מסה מרשימה ביותר בבקיאותו, בחריפותו, בפלפולו בתקיפותו של המחבר לאורך כמאה עמודים גדושים, שבה סיכם כמעט כל מה שנאמר לפניו בנושא… בתשובה זו מתגלה המחבר כחכם בקי, תמים ובעל חושב ביקורתי כאחת, שכל רז לא אניס ליה, לא בספרות הרבני ולא במחקרי זמנו, והוא מצליח לגייס את ידיעתיו להגצת עמדתו… ואין פלא כלל שתשובה מרשימה זו כבשה במהרה את הלבבות והייתה למילה אחרונה בנושא ודעתו נתקבלה כמעט על כל החוקרים [מחקרי תלמוד, ג, עמ’ 235].

[10] For more sources on this, see: Rabbi Oberlander, Minhag Avosenu Beyadneu, (Shonot), pp. 11-19; R’ Yechiel Goldhaber, Minhaghei Hakehilot, 1, pp. 174-175; Eliezer Brodt, Yerushaseinu 2 (2008), pp. 203-204; Rabbi Y.M. Dubovick, Minucha Sheleimah (2014), pp.26-27.

[18] On R’ Ganzfried, see R’ Y. Rubinstein, HaMayan 11:3 (1971), pp. 1-13; ibid. 11:4. pp. 61-78. See also Naftoli Ben Menachem, HaMayan 12 :1 (1972) pp. 39-42. On this controversy, see R’ Rubenstein, ibid. pp. 10-11. On R’ Weber, see Naftoli Ben Menachem, in: Studies in Jewish bibliography, history, and literature in honor of I. Edward Kiev, Charles Berlin (editor), New York 1971, pp. 13-20. On this broadside, see Shoshanna Halevy, Sifrei Yerushlayim Ha-Rishonim, p. 188. On the other works by R’ Weber related to this issue, see ibid, pp. 156-157, 186-187, 219-220. See also Moshe Carmilly, Sefer VeSayif, pp. 264-265.

For an additional controversy between the Divrei Chaim and R’ Ganzfried see David Assaf, HeTzitz Unifgah, (2012) pp. 362-367.

About R’ Ganzfried and Chasidim, see Heichal HaBesht 3 (2003), pp. 105-117. For more on the Divrei Chaim’s methods of Pesak, see Iris Brown, Rabbi Hayyim Halberstam of Sanz: His Halakhic Ruling in view of his Intellectual world and the challenges of his time, (PHD Bar Ilan University) 2004 (heb.).