Keser vs. Kesher: What’s In A Name?

Keser vs. Kesher: What’s In A Name?[1]

I – The Puzzle

Kesher Israel (KI) Congregation has enhanced Jewish life in Pennsylvania’s capital of Harrisburg for almost 115 years. During that time, KI has been blessed with outstanding rabbinic leadership: The famed Rabbi Eliezer Silver[2] first headed the congregation from 1911-1925. He was followed by Rabbi Chaim Ben Zion Notelovitz who served KI from 1925-1932. Rabbi David L. Silver (a son of Rabbi Eliezer Silver) led the congregation from 1932-1983. Rabbi Dr. Chaim E. Schertz served KI as its rabbi from 1983-2008.

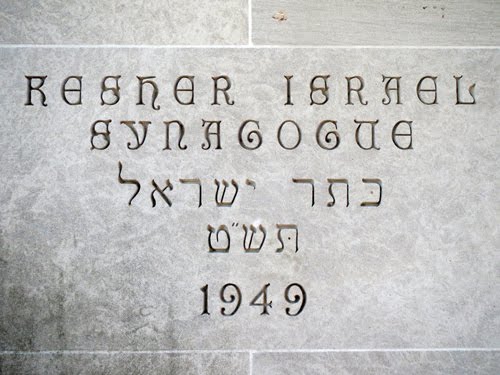

Soon after arriving in Harrisburg in 2007, I found myself intrigued by the synagogue’s name. Since the congregation is called Kesher Israel, I just assumed its Hebrew name was קשר ישראל (pronounced ‘Kesher Israel’, meaning Bond of Israel). However, I soon learned that upon being founded in 1902, the synagogue was in fact named כתר ישראל (pronounced ‘Keser Israel’ in classic Ashkenazis – which KI’s founders surely spoke – meaning Crown of Israel). I soon noticed that below the words ‘Kesher Israel Synagogue’ on the cornerstone of KI’s current building (pictured above), appears the Hebrew name כתר ישראל.

This seemingly minor detail puzzled me greatly. Why did a congregation whose proper Hebrew name was כתר ישראל choose to call itself Kesher Israel? Had anyone ever taken note of – or attempted to correct – this inconsistency? During the summer of 2015, I found time to research the matter, and I now have a theory to propose.

II – An Enigmatic Account

In 1997, KI honored its beloved Rabbi Emeritus – Rabbi David L. Silver (1907 – 2001)[3] – with a community-wide weekend celebration on the occasion of his 90th birthday. As part of that celebration, the congregation published “Silver Linings” – a 90 page book of Rabbi D. Silver’s memoirs. Those memoirs were excerpted from some 35 hours of taped interviews conducted from April, 1996 – April, 1997. On pages 43 – 44 of that book we find the following account:

When the shul was founded, it was called Keser . . . which means a crown. Some fellow who was a Hebrew teacher . . . spelled it as C-a-s-s-e-u-r. He should have put it down as K-e-s-e-r. Some people – Lithuanian Jews, I want you to know, because I am of that breed – pronounced and spelled it “sh”. Kesher means “the bond” . . .

My father came here in 1907. He was a good Hebraist and he didn’t like the name. He said, in the Bible when there is the term “kesher” it’s “kesher bodim”[4]. A bond of bodim means rebels, period[5]. My father said that’s no name for a shul and changed it from Kesher Israel to Keser Israel, a crown of Israel. I don’t know whether it happened on the first day he came here but that’s what it became.

Rabbi D. Silver’s eye-opening account of the history of KI’s name is quite enigmatic. In attempting to understand this explanation, the following questions must be answered:

1) If the congregation’s original name was in fact ‘Keser Israel’ (כתר ישראל), why would Lithuanian Jews have pronounced it ‘Kesher Israel’?

2) If the congregation’s original name actually was ‘Keser Israel’, what exactly did Rabbi Eliezer Silver change?

3) As the synagogue is called ‘Kesher Israel’ to this very day, what did Rabbi D. Silver mean when he reported that his father had successfully changed its name from ‘Kesher Israel’ to ‘Keser Israel’?

III – Sabesdiker Losn

In the Book of Judges, we learn of a terrible civil war that flared up between the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh. As the beaten forces of Ephraim attempted to retreat across the Jordan River we read (Judges 12:5-6):

5 – And the Gileadites seized the crossings of the Jordan that belonged to Ephraim; and it was that when any of the survivors of Ephraim said, “Let me go over,” and the men of Gilead said to him, “Are you an Ephraimite?” and he said, “No.”

6 – And they said to him, “Say now ‘Shibboleth,’ ” and he said “Sibboleth,” and he was not able to pronounce it properly, and they grabbed him and slew him at the crossings of the Jordan; and there fell at that time of Ephriam, forty-two thousand.

At that point in Jewish history, the tribe of Ephraim was unable to correctly pronounce the hushing sound of the Hebrew letter “Shin” in the word “Shibboleth”. They instead pronounced the word with the hissing sound of the Hebrew letter “Sin”, and the word came out as “Sibboleth”.[6] With their identities compromised, many Ephraimites lost their lives.

In the course of my research, I learned that the inability of many Lithuanian Jews to properly distinguish between the hushing and hissing sounds of the Hebrew letters “Shin” and “Sin” was once common knowledge. Like the Ephraimites before them, many Lithuanian[7] Jews also pronounced the word ‘Shibboleth’ as ‘Sibboleth’.[8] As a result of their enunciation, other Yiddish speakers jokingly referred to the Lithuanian dialect of Yiddish as ‘Sabesdiker Losn’. In an often quoted article on Sabesdiker Losn, Prof. Uriel Weinreich writes:

One of the most intriguing instances of non-congruence involves a peculiar sound feature of the northeastern dialect of Yiddish: the confusion of the hushing series of phonemes (š, ž, č) with the hissing phonemes (s, z, c), which are distinguished in all other dialects . . . This dialect has come to be known as sábesdiker losn ‘solemn speech’ (literally ‘Sabbath language’), a phrase which in general Yiddish is šábesdiker lošn, with two š’s and an s. This mispronunciation of it immediately identifies those who are afflicted with the trait; to them the term litvak is commonly applied.[9]

Later in that same article Weinreich writes:[10]

The Ephraimites . . . paid with their lives for their inability to distinguish hissing and hushing phonemes in a crucial password. No litvak has ever been slain for his sábesdiker losn, but he has been the butt of innumerable jokes. The derision with which the feature was regarded by other Yiddish speakers sent it reeling back under the impact of “general Yiddish” dialects from the south . . . In addition to dialectical pressure from the south, there were other influences tending to introduce the opposition, as it were, from within. There was for example, the growing need to learn foreign languages in which hissing and hushing phonemes are distinguished, and the promotion of Standard Yiddish by the schools, the theater, and political and educational organizations.[11]

As we have seen, many Lithuanian Jews were unable to distinguish between hushing and hissing sounds. While this led many to pronounce ‘Shibboleth’ as ‘Sibboleth’ (hence the term Sabesdiker Losn), this was not always the case. There is much evidence that in some locales, the inability of Lithuanian Jews to distinguish between the hushing and hissing sounds resulted in the exact opposite: they pronounced the word ‘Sibboleth’ as ‘Shibboleth’.[12]

In his article dealing with Sabesdiker Losn, Prof. Rakhmiel Peltz[13] quotes sources showing that many Lithuanian Jews mispronounced their words in the following manner:

. . . šuke ‘Sukkoth tabernacle’, šimkhe ‘joy, festivity’, šeykhl ‘reason, sense’, šider ‘prayer book’ . . . [14]

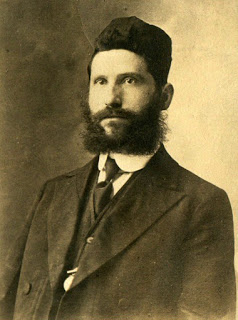

A fascinating episode involving none other than Rabbi Eliezer Silver himself relates to this point, and can be found in the book “A Fire In His Soul”. A good part of that volume documents the activities of the Vaad Hatzala – the emergency rescue committee which worked so hard to save Jewish lives during the dark years of the Holocaust.[15] Soon after the fighting ended, the committee sent Rabbi E. Silver to the war-ravaged European continent to aid Jewish refugees and survivors. The following colorful incident is recorded:[16]

Rabbi Eliezer Silver, acting as a Vaad representative and president of the Agudas Harabonim, spent three months visiting Holland, Belgium, France, Czechoslovakia, Germany and Poland. Wearing a surplus American Army uniform purchased for this mission, he moved about freely, distributing funds to build mikvaos, yeshivas and kosher kitchens. He also located children who had been in hiding throughout the war.

This bearded rabbi in uniform did experience some awkward moments. When an allied soldier saluted him, Rabbi Silver did not respond in kind, causing the soldier to doubt his credentials. When Occupation officials asked to see his military identification – after all, he was a man in uniform – Rabbi Silver stared defiantly and proclaimed, “I don’t need papers. I am the Chief Rabbi of the United States and Canada!” (It came out “United Shtates” in Rabbi Silver’s characteristic accent.) Understandably, the American authorities did not believe him and were not inclined to let him go.

Chagrined, Rabbi Silver pointed to the telephone and barked, “Call Shenator Taft. Tell him Shilver’s here!” The officials looked at each other. They didn’t know that the small man, seething with almost comical anger, enjoyed a personal and political friendship with the powerful Ohio Senator Robert Taft.[17]

Rabbi Silver’s “characteristic accent” described above is a rare glimpse into how his Lithuanian upbringing and pronunciations affected his ability to articulate his words. Rabbi Eliezer Silver was born in the hamlet of Abel – in the Kovno province of Lithuania in 1881.[18] His pronunciation of “Shtates”, “Shenator”, and “Shilver” was most likely the result of his growing up in an environment where no distinction was made between hissing and hushing sounds in the Yiddish spoken all around him. In his case (and probably in the case of many others in his locale), words that should have been pronounced with a ‘hiss’, were instead pronounced with a ‘hush’.[19]

With this better understanding of how many Lithuanian Jews pronounced their words, I believe we can now solve the mystery of KI’s name.

IV – Solving the Puzzle: A Theory

Making use of KI’s historical records, I propose the following theory:

KI was founded in 1902. The congregation was officially named כתר ישראל in Hebrew, and was given the English name of ‘Casseur Israel’ – instead of the more straight-forward ‘Keser Israel’. This can be clearly seen from a document – dated January 1, 1903 – presented to Mr. Max Cohen (a founding member) which stated that he had purchased a pew in his new Harrisburg synagogue. This certificate was signed on behalf of “The Trustees of the Congregation – Casseur Israel, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania”. The document was also embossed with the new congregation’s official seal. In English, the stamp reads “Congregation Casseur Israel – Harrisburg, Pa.” In Hebrew it reads, “חברה כתר ישראל – האריסבורג פא” [20]

Although KI was chartered as ‘Casseur Israel’ in October of 1902, the Lithuanian founders and members of this new synagogue pronounced its name as ‘Kesher Israel’. This was a result of the manner in which their version of Sabesdiker Losn Yiddish affected their enunciation of the hissing and hushing sounds.[21] As a result of the way in which the congregation’s members pronounced their own synagogue’s name, local newspaper articles began referring to the synagogue as ‘Kesher Israel’ – as early as 1903 (just months after the congregation was founded).[22]

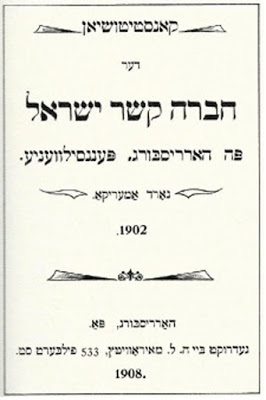

Though Rabbi Eliezer Silver arrived in Harrisburg in 1907, he was not officially hired by KI to serve as their spiritual leader until February 11, 1911.[23] In 1908, shortly after Rabbi E. Silver arrived in Harrisburg – but still three years before he would become KI’s first rabbi – the six-year-old congregation hired a local Yiddish printer to write up its constitution.[24] The following detail on the constitution’s cover page[25] is striking: Although the synagogue’s official seal used in 1903 listed the new congregation’s Hebrew name as חברה כתר ישראל (Keser Israel Congregation), KI’s 1908 constitution records the Hebrew name of the synagogue as חברה קשר ישראל (Kesher Israel Congregation).[26] This was a result of either:

A) The printer – unfamiliar with the congregation’s official Hebrew name of כתר ישראל – published a document in which he spelled the congregation’s Hebrew name true to the way its own members all pronounced it – קשר ישראל – Kesher Israel.

B) The version of Lithuanian Yiddish spoken by so many of the congregation’s founders and members caused them to refer to the synagogue as ‘Kesher Israel’ from the day it was founded. Perhaps by 1908 a movement arose within KI to have its Hebrew name officially changed from כתר ישראל (Keser Israel) to קשר ישראל (Kesher Israel). This proposed switch would enable the young congregation to have complete consistency between; 1) the synagogue’s Hebrew and English names, 2) what all of KI’s founders and members already called it, and 3) the name used by all the newspapers when referring to the congregation.

When KI hired Rabbi Eliezer Silver as its rabbi in 1911, he accepted the pulpit of a synagogue whose Hebrew name had begun as כתר ישראל (Keser Israel), but for one reason or another, was now given the Hebrew name of קשר ישראל (Kesher Israel) in its official constitution. Rabbi E. Silver could live with the fact that everyone pronounced the congregation’s name as ‘Kesher Israel’ (and from what we have seen above, he most probably pronounced it that way as well) – and did not even mind if they spelled it that way in English. However, seeing the synagogue’s name spelled in Hebrew as קשר ישראל was too much for Rabbi E. Silver to bear. Having mastered Biblical and rabbinic literature, he clearly knew the negative connotations of the word קשר . He associated that word with conspiracies and rebellions – concepts which he strongly believed had no place in a Jewish house of prayer that was to be loyal to G-d and Jewish tradition. As such, Rabbi E. Silver insisted that KI’s official Hebrew name should revert back to כתר ישראל (Keser Israel). He insisted on this Hebrew name for the synagogue despite the fact that (he and) his fellow Lithuanian Jews pronounced the congregation’s name as ‘Kesher Israel’ – and would continue spelling it that way in English as well.[27]

Rabbi E. Silver’s efforts to ensure that KI would retain its original Hebrew name of כתר ישראל (Keser Israel) can be seen in two early projects of his.

A) Upon his arrival in Harrisburg, Rabbi E. Silver instituted a Hevra Shas – wherein he studied the Talmud together with members of Harrisburg’s Jewish community each morning and evening.[28] Rabbi Silver’s Hevra Shas moved into KI’s facility after he became its rabbi in February of 1911.[29] A large hand painted sign proudly displaying the names of the dedicated members (and supporters) of that Talmud study group was created – and still hangs in one of KI’s offices. At the top of that sign, the following Hebrew words appear: בית הכנסת כתר ישראל חברה ש”ס – האריסבורג, פא. (Keser Israel Synagogue Hevra Shas – Harrisburg, PA.).[30] The wording of KI’s name on that sign reflects Rabbi E. Silver’s goal of reclaiming כתר ישראל as the congregation’s official Hebrew name.

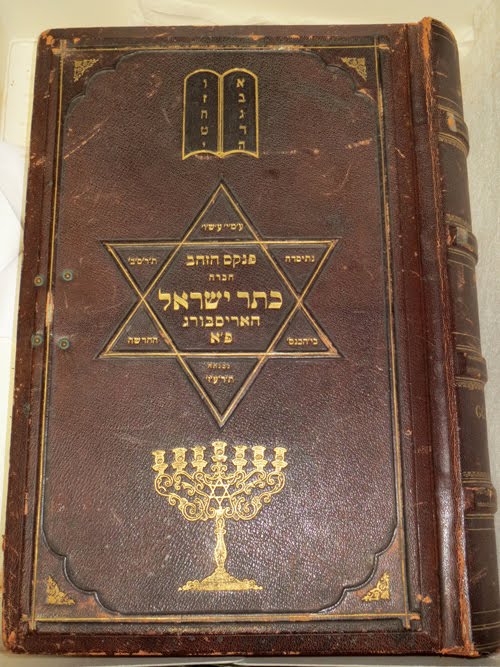

B) In 1917, KI commissioned an artisan to create a special ‘Pinkus HaZahav’ or Golden Book. This incredibly large and heavy leather-bound volume (hand-written in beautiful Hebrew calligraphy) contains a brief history of the congregation.[31] The bulk of the volume consists of a ledger listing the names of those who had made significant pledges towards the new building KI would soon move into. [32] On the book’s front cover, the congregation’s name is written in Hebrew as חברה כתר ישראל. Like the Hevra Shas sign, the wording of KI’s name on its special Golden Book reflects Rabbi E. Silver’s goal of reclaiming כתר ישראל (Keser Israel) as the congregation’s official Hebrew name.[33]

In addition to explaining Rabbi David L. Silver’s above-cited enigmatic account, I believe the puzzle of how a synagogue, with the Hebrew name of כתר ישראל (Keser Israel), ended up with the English name of ‘Kesher Israel’ has now been solved.

VI – Conclusion

Upon reflection I realize that the only time the membership of KI hears the congregation referred to as כתר ישראל (Keser Israel) is after the solemn Yizkor memorial prayers, which are recited during the holidays. At the conclusion of Yizkor, special collective Kel Maleh memorial prayers are recited on behalf of the deceased members and relatives of the congregation.[34] Since my arrival in 2007, I listened closely as KI’s Cantor Seymour Rockoff would clearly enunciate the words קהילת כתר ישראל (Keser Israel Congregation) during that prayer – pronouncing the synagogue’s Hebrew name exactly as Rabbi Eliezer Silver would have wanted.

Following Cantor Rockoff’s sudden passing in the summer of 2015,[35] I recited those collective Kel Maleh prayers at KI this past Shemini Atzeret (5776). As I clearly pronounced the words קהילת כתר ישראל, I thought about all the history behind KI’s name. I also envisioned Rabbi Eliezer Silver grinning as he tipped his signature black silk top hat in my direction.

___________

רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, שְׁלשָׁה כְתָרִים הֵם, כֶּתֶר תּוֹרָה וְכֶתֶר כְּהֻנָּה וְכֶתֶר מַלְכוּת, וְכֶתֶר שֵׁם טוֹב עוֹלֶה עַל גַּבֵּיהֶן.

Rabbi Shimon would say: There are three crowns – the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood, and the crown of royalty – but the crown of a good name is the most valuable of them all.

(Pirkei Avot 4:13)

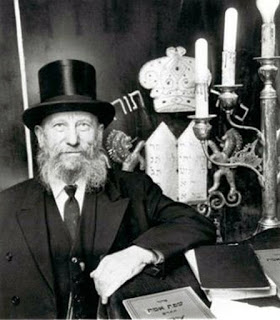

Rabbi Eliezer Silver in his younger and older years.

[1] This article is dedicated to the memory of Cantor Seymour Rockoff – Harav Eliyahu Shalom ben Harav Chaim Shmuel, z”l. With his melodious voice and meticulous attention to the details of prayer, Cantor Rockoff greatly enhanced Kesher Israel Congregation’s services from 1986 – 2015.

[2] (1882-1968). For an excellent biography of Rabbi E. Silver, see Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Aaron. The Silver Era: Rabbi Eliezer Silver and His Generation. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1981. This out-of-print book was republished by the Orthodox Union and Yeshiva University Presses in 2014.

[3] Yeshiva University placed an obituary for Rabbi D. Silver – one of its oldest rabbinic alumni – in The New York Times on July 11, 2001. It can be viewed online here.

[4] I am confident that the word Rabbi D. Silver used in the interview from which this account was excerpted was “Bogdim” and not “Bodim”. The term “Kesher Bogdim” means a band of traitors, and can be found in Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah Hilkhot Sanhedrin 2:14, Shulhan Arukh Hoshen Mishpat 3:4, and according to the Vilna Gaon (note 22 there) the expression is based on the term “Kesher Reshaim” – a band of evil-doers – used by the Talmud in BT Sanhedrin 26a.

[5] For examples where the word ‘Kesher’ is used in describing conspiracies in the Bible see: I Samuel 15:12, I Kings 16:20, II Kings 11:14, II Kings 12:21, II Kings 14:19, II Kings 15:15, II Kings 15:30, and II Kings 17:4.

[6] In his commentary to Judges 12:6, Rabbi Dovid Kimhi (1160 – 1235) notes that in his day, many in France were also unable to properly pronounce the hushing sound of the letter “Shin”.

[8] See Turei Zahav note 30 to Shulhan Arukh Orah Haim 128:33

[9] Weinreich, Uriel. (1952). Sábesdiker Losn in Yiddish: A Problem of Linguistic Affinity. Word, 8, page 58. I thank Vilnius-based Professor Dovid Katz for making me aware of this important article.

[10] Ibid, page 70.

[11] While researching this topic, I took note of the fact that while Sabesdiker Losn was such a new concept to me, many Yeshiva graduates in their sixties whom I interacted with instantly recognized this phenomenon. Several shared with me fond memories of their older Lithuanian-born and educated teachers who would refer to ‘Rasi’ instead of ‘Rashi’. (For one such light-hearted published account see page 40 in Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Aaron. From Washington Avenue to Washington Street. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House / OU Press, 2011.) Why then was the concept of Sabesdiker Losn so new to me? I soon realized that in addition to Prof. Weinreich’s explanations (above) regarding the disappearance of Sabesdiker Losn, there was another factor which he never could have foreseen: the utter decimation of Lithuanian Jewry during the Holocaust. As a child who only began his Jewish day school education in the late 1970’s, I simply never had the chance to interact with authentic Lithuanian-born and educated teachers like many Yeshiva graduates a generation or two older than me had.

[12] As such, this version of Lithuanian Yiddish might be described as “Shabeshdiker Loshn”. I thank Dr. Edward Portnoy of Rutgers University’s Department of Jewish Studies and YIVO’s Academic Advisor, as well as Isaac Bleaman – a doctoral student in the Department of Linguistics at New York University – for clarifying this important point for me.

[13] Peltz, Rakhmiel. (2008). The Sibilants of Northeastern Yiddish: A Study in Linguistic Variation. In Kiefer, Ulrike and Neumann, Robert and Herzog, Marvin and Sunshine, Andrew and Putschke, Wolfgang (eds.), EYDES (Evidence of Yiddish Documented in European Societies), 241-274. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter – Max Niemeyer Verlag. Page 255.

[14] Peltz also notes (page 255) that some Lithuanian Jews even confused the hissing and hushing sounds within the same term / phrase. For example, some might refer to a house of study / prayer as the bešmedres instead of besmedraš. One rabbi I communicated with told me he remembered hearing a highly-regarded Lithuanian-born and educated rabbi refer to his NY study hall as the bešmedres.

[15] For more information on Rabbi E. Silver’s work with the Vaad Hatzala, see Rakeffet-Rothkoff (ibid.) pages 186-250.

[16] Bunim, Amos. A Fire in His Soul: Irving M. Bunim, 1901-1980, the Man and His Impact on American Orthodox Jewry. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1989. Pages 166-7.

[17] The story concludes with Senator Taft eventually being reached in Washington, DC. After vouching for Rabbi Silver, the rabbi was released and allowed to continue his mission on behalf of the Vaad Hatzala.

[18] Rakeffet-Rothkoff (ibid.) page 43.

[19] In addition, Rabbi Hershel Schachter of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary related to me that he remembers hearing Rabbi Eliezer Silver pronounce Cincinnati – the city where he served as rabbi for close to 40 years – as “Shinshinati”.

[20] Pictures of this document and its accompanying stamp can be seen in KI’s 75th Anniversary Yearbook (1977) pages 5 – 6.

[21] i.e. they pronounced the word ‘Sibboleth’ as ‘Shibboleth’. In suggesting an explanation for KI’s name, someone already alluded to this point on the Shul’s Wikepedia page (here) with the following sentence: “One explanation is that the “s” and “sh” sounds were conflated in the Lithuanian Yiddish pronunciation of the time.” This was attributed to the following sentence on YIVO’s website (here):” . . . much traditional Lithuanian Yiddish collapses the hushing and hissing consonants (“confusion of sh and s sounds”), a feature most Litvaks have tried to overcome in recent generations.” See footnote 12.

[22] See for example, (1903, April 2). Jewish Synagogue Gets a Cemetery. Harrisburg Daily Independent, page 1, and (1903, April 9). Passover Services. HarrisburgTelegraph, page 3.

[23] See KI’s 75th Anniversary Yearbook (1977), page 4, and Rakeffet-Rothkoff (ibid.) page 53 which record that from 1907 – 1911, Rabbi E. Silver served the entire Orthodox Jewish community of Harrisburg – and was not employed by any one congregation exclusively.

[24] Interestingly, like Rabbi E. Silver, it seems that KI’s Lithuanian founders were also from the Kovno region. One finds the directive to follow the customs of Kovno at least twice in KI’s constitution (see KI constitution pages 8 and 22).

[25] A picture of this constitution’s cover page appears on page 5 of KI’s 75th Anniversary Yearbook. I thank Rabbi Ahron Silver (Rabbi David L. Silver’s son) of Jerusalem, Israel for e-mailing me photos he took of this important historical document. I also thank KI’s Dr. Sandy Silverstein and Dr. Mark Cohen for helping me obtain an original copy of this constitution.

[26] The congregation is referred to as קשר ישראל several times within the constitution as well – but never as כתר ישראל.

[27] It seems that while Rabbi Eliezer Silver was quite concerned with the congregation’s Hebrew name, he did not concern himself in ensuring the congregation’s English name would be firmly registered as ‘Keser Israel’. I would suggest that the spelling of the synagogue’s English name was of little or no concern to Rabbi E. Silver. After all, it was the Hebrew word קשר which conjured up all sorts of negative connotations in his mind – not the English transliteration of that word.

[28] Rakeffet-Rothkoff (ibid.) page 54, and KI’s 75th Anniversary Yearbook (1977), page 4.

[29] Kesher Israel’s 1949 Dedication Book page 11. Interestingly, this book was published the same year it dedicated its new building. Just like the congregation’s new cornerstone, the Dedication Book records the Hebrew name of KI as כתר ישראל, and its English name as ‘Kesher Israel Synagogue’.

[30] Just beneath the words:בית הכנסת כתר ישראל חברה ש”ס – האריסבורג, פא. (Keser Israel Synagogue Hevra Shas – Harrisburg, PA.) on that sign, appear the words: נתיסדה ע”י הרב מהר”א זילבער שליט”א, זאת חנוכה התרס”ח (Established by the rabbi our teacher Rabbi Eliezer Silver, may he live for many good and long days, the 8th day of Hanukah, 5668). That date corresponds to December 8, 1907. While the Hevra Shas may have begun studying the Talmud together in Harrisburg on that date, KI would not have created this sign – which claimed the Hevra Shas as its own – until some time after February of 1911 when Rabbi E. Silver officially became KI’s rabbi.

[31] For a nice write-up on this special book, see here.

[32] Though the book contains several hundred pages, only the first 16 were ever used.

[33] On the book’s back cover, KI’s name is written in English as ‘Keser Israel Congregation’. That is the only example I could find where KI’s English name was ever officially recorded that way.

[33] On the book’s back cover, KI’s name is written in English as ‘Keser Israel Congregation’. That is the only example I could find where KI’s English name was ever officially recorded that way.

[34] While only those who have lost a parent remain in the sanctuary during the actual recitation of Yizkor, the entire congregation gathers again in KI’s sanctuary for the collective Kel Maleh prayers once Yizkor has been completed.

[35] For more on Cantor Rockoff, see here.

One thought on “Keser vs. Kesher: What’s In A Name?”

if you register with this link send me email with your name(same of moneyguru) and your referral link in this email money@love-seo.com i make you 10k of free premium backlinks win MAX money