The “Doctored” Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menasseh Ben Israel: Forgery or “For Jewry”?

The “Doctored” Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menasseh Ben Israel:[1] Forgery or “For Jewry”?

Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

Menasseh ben Israel is a prominent figure in Jewish history known for his role in the return of the Jews to England in the time of Oliver Cromwell, as well being the first to establish a Hebrew printing press in Holland.[2] Menasseh had two sons and a daughter. His son Samuel, born in 1625, was a Hebrew printer,[3] publishing a number of his father’s works, and also assisting his father with his diplomatic endeavors in England. Here we focus on another aspect of Samuel’s life- his medical career.

In a correspondence dating from the mid seventeenth century, we find information about Samuel’s medical training and degree. The letter, dated Tammuz, 5416 (1655), is from Yehuda Heller Wallerstein to Samuel Ben Israel. Yehuda writes from Salonica and reports how he encountered Jan Nicholas, the brother of Sir Edward Nicholas, British politician and advocate for the resettlement of the Jews in England, who enlightened him as to Samuel’s recent activities: “He informed me that in a short period of time you achieved great success in your study of the sciences and merited, with the assistance of Edward his brother, to present for examination before the professors of the University of Oxford, and to obtain the distinction, ‘Doctor of Medicine and Philosophy’.”[4]

There would appear to be no reason to doubt this account. Menasseh was certainly connected to the influential Sir Edward Nicholas, whose work advocating for the Jews return to England he translated. Samuel is in fact known to have been a physician. However, this account is found in the writings of Abraham Shalom Friedberg, master of historical fiction. While Samuel is an historical figure, Heller Wallerstein is a likely a figment of the author’s imagination and the letters are primarily a vehicle to explore the historical chapter of Shabbetai Zevi, the false messiah, for which this account of the diploma is only peripheral.

The only historical source, upon which the remainder of this fanciful account revolves, is a medical diploma from the University of Oxford granted to Samuel ben Israel on May 6, 1655,[5] and even the veracity of this document is suspect. A number of historians have discussed this diploma, primarily through the lens of Samuel’s famous father Menasseh, and have concluded that it is a forgery. Here we introduce a new perspective to this discussion and view the diploma from the vantage point of Jewish medical history, an aspect strikingly absent from previous discussions. It is only through this lens that we can gain an accurate assessment of its content and context. Was it really a forgery, or merely a product of the historical realities of its age?

A Word on the Medical Training of Menasseh ben Israel, Samuel’s Father

As a backdrop to our discussion about Samuel’s medical training, it is instructive to analyze the medical qualifications and practice of his father. Aside from his activities as a rabbi, statesman and author, Menasseh was also a physician.[6] The medical face of Menasseh has received scant treatment by historians, and perhaps for good reason. It was clearly not a major aspect of his daily life or contribution to Jewish history. His medical personality was manifest only peripherally or secondarily, and inconsistently as well. Nonetheless, understanding Menasseh’s medical identity sheds light not only on Jewish medical history in general, but also on his son’s medical training.

In a number of published works Menasseh refers to himself as a physician. In his letter to the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, published in 1655, the very same year as Samuel’s diploma, he is identified as a “Doctor of Physick.”

In the work below from 1656 he is called a physician:

Menasseh also referred to himself as “Medicus Hebraeus.”[7] This title was also used to describe Ephraim Bueno, a prominent Amsterdam physician, as well as a friend and supporter of Menasseh.[8] Furthermore, his connection to medicine is reflected in his translation of the aphorisms of Hippocrates into Hebrew [9] and his relationships with a number of physicians.[10]

To my knowledge there is no record of Menasseh obtaining a medical diploma or graduating from a university. One scholar writes, without reference, that he attended medical school at the University of Groningen for a short time, though apparently did not complete his degree.[11] I have seen no evidence to corroborate this assertion and the university has no record of his matriculation in their archives.[12]

Menasseh’s identification as a physician was not consistent. In some works, the medical title is omitted:

Another curious fact is that Menasseh’s Hebrew writings make no mention whatsoever of his role or title as a physician, nor have I seen him identified as a rofeh in any Hebrew literature. Roth suggests that he may have practiced, though evidence is lacking, and that he included his address when he identified as a physician in his English works as a form of advertising.[13] The tombstone of Menasseh in the Ouderkerk Cemetery does not bear the title doctor or physician.[14]

While historians are wont to call Samuel’s diploma a forgery, his own father considered himself a physician without obtaining a degree or diploma. Should we not, to be consistent, consider Menasseh an imposter physician?

Essential to our assessment of the medical titles and careers of both Menasseh and his son is an understanding of the training of Jewish physicians at this period in history. While today the notion of a physician without formal university training culminating in a diploma is anathema, not to mention criminal, this was simply not the case in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, particularly for the Jew. In fact, Jews were universally barred from attending or graduating universities, which were invariably under the auspices of the Catholic Church. Graduation from universities, such as Oxford, included and required statements or oaths avowing one’s belief in Christianity.

This did not prevent Jews from becoming physicians. They pursued an alternate medical educational pathway comprised of independent learning and clinical training through apprenticeship.[15] This enabled them to take licensing exams and earn the title doctor. Some simply self-identified as a physician or rofeh by virtue of their extensive training. The overwhelming majority of Jewish physicians trained through this alternate pathway, and it is likely that Menasseh is counted amongst them. Once universities began to open their doors to Jewish students,[16] a number of academically motivated students chose this conventional pathway. These university-trained physicians initially accounted for only a small percentage of the health professionals in the Jewish community. Thus, the title “rofeh” or “doctor” in this period was not specifically associated with a university degree.[17]

The Medical Diploma of Samuel ben Israel

The full text of Samuel’s medical diploma was first printed by Koenen in 1843.[18] Koenen raises no doubts whatsoever as to the veracity of the document and publishes it, without discussion, comment or context, as part of a collection of important documents in Dutch Jewish history. Through what training or means Samuel attained this diploma is entirely omitted.

After its publication, the diploma was initially accepted by historians and scholars without question. For example, G. I. Polak wrote that Samuel, through extraordinary skill and acumen, was able to obtain his degree in medicine and philosophy from Oxford.[19] Some even took the liberty to provide additional details. For example, Graetz writes in his classic History of the Jews:[20]

Samuel ben Israel … was presented by the University of Oxford, in consideration of his knowledge and natural gifts, with the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and Medicine, and according to custom, received the gold ring, the biretta, and the kiss of peace.[21]

Where could Graetz have derived this detailed information? It actually appears in the Latin text of Samuel’s diploma, which describes the features of the classic graduation ceremony for European universities during this period. The biretta, often called the Oxford Cap, is the ancestor of our contemporary four-cornered graduation cap.

The scholar Adolph Neubauer appears to have been the first person to suspect something was not kosher with Samuel’s credentials, and at his behest, in 1876, Richard Griffith, the Keeper of the Archive at the University of Oxford reviewed the text of the diploma.[22] The following are the summary points of his analysis:[23]

- Samuel is not mentioned in the Registers of the university as having ever attended or received a degree.

- Degrees from Oxford were not issued in the month of May, the date of the diploma.

- The diploma is signed by two specific people, while the typical Oxford degree is conferred by the university and bears a seal, without the signature of any specific person.

- The degree is granted in both philosophy and medicine, and Oxford never granted degrees in philosophy, either alone or combined with medicine.

- There are multiple phrases not used in the Oxford diploma and multiple procedural aspects referred to that simply were not part of Oxford’s protocols.

Griffith’s inescapable conclusion is that this is unequivocally not a genuine Oxford diploma. His analysis is unassailable. Griffiths was certainly familiar with the text of the medical degrees from Oxford during Samuel’s time; indeed, he literally wrote the book on the subject.[24]

Based on Griffith’s analysis, Samuel’s diploma is so fundamentally different than the standard Oxford diploma, there would seem to be no reason to obtain an actual Oxford diploma from that time to further compare the two. Even if one were to consider such a comparison, it would be challenging if not impossible to find an extant diploma from Oxford contemporary with Samuel. In response to my query, the Oxford Archives today responded that they do not possess any diplomas from this period, nor, for that matter, are they aware of any held elsewhere. The archivist added that they cannot be sure that diplomas or degree certificates, in the sense we understand the term, were even created or issued at Oxford from the 15th to the 17th centuries. As mentioned, there was however a specific template and wording associated with the granting of degrees at Oxford,[25] and the graduate would receive some confirmation of their degree, albeit perhaps not a formal diploma in the classic sense. The document did however bear the university seal. It is upon this Oxford template that Griffith based his analysis.

After negating any connection to Oxford, Griffith adds that the diploma was rather an adaptation of a form then used by the University of Padua, “with alterations willfully and insufficiently made.” Griffith was familiar with the Padua diploma template from his Oxford position for a curious reason. In the seventeenth century many graduates in medicine desiring to practice in England obtained their degrees outside of the United Kingdom, often at the University of Padua. In order to practice in England, the graduate had to be “incorporated” into either the University of Oxford or Cambridge. As a prerequisite to incorporation the students were required to present their diplomas/degrees from the granting institution.[26]

The Location of the “Original” Diploma

While Koenen published the full text of Samuel’s diploma, he makes no reference as to the location of the original document. Roth notes that he received a photo of the diploma from the Montezinos Library (known today as Ets Haim- Livraria Montezinos) in Amsterdam. A catalogue of the library holdings from 1927[27] states that the library possessed copies of the first and last pages of the diploma, though not the original.[28] The Ets Haim Library today does not have a record of the diploma photographs.[29] I reached out as well to the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, the other major Jewish historical collection in Amsterdam, to see if perhaps the diploma ended up there, which it did not.[30] I also contacted the Roth Collection at the University of Leeds to see if perhaps Roth’s copies of the diploma are kept there, and to my dismay, they likewise have no record of Samuel’s diploma.[31]

Without the actual document, it is impossible to definitively comment on its veracity. Access to the original would allow analysis of the ink and paper for dating. Even access to the copies would be useful. For example, the diploma contains signatures of two faculty members of the University of Oxford. A comparative graphological analysis with known signatures of these men could easily confirm the document’s origin. Regretfully, I have access to neither the “original,” nor the copies. I nonetheless offer additional information and analysis in defense of a Jewish physician accused of forgery in the hopes of restoring his reputation. Absent such essential material information for my case, you may feel free to conclude that my diploma (analysis) is a forgery of sorts. I hope to nonetheless persuade you to drop the charges of forgery, though definitive proof beyond a shadow of a doubt awaits the discovery of the “original” diploma.

Was the diploma a forgery?[32]

Samuel’s diploma was beyond doubt not an official Oxford-issued document, as Griffith details, but was it necessarily a forgery? All historians to date familiar with Griffith’s analysis assume the answer to be a resounding yes, some even labelling it a “brazen” forgery.[33] There is no evidence of any suspicion of the document’s veracity during the lifetime of its bearer. As to when the document was supposedly forged, while the theoretical possibility exists that the diploma was a product of the nineteenth century, Roth convincingly dismisses this theory. He concludes, “The hypothesis of a nineteenth-century fabrication may thus be definitely ruled out.”[34] We are thus left with the universally accepted belief that Samuel forged his own diploma.

Kayserling notes that Menasseh, and thus Samuel, had not yet visited England in May of 1655, the date of the document. This would seemingly conclude the case for forgery and leave little room for discussion. Roth however subsequently rejected this assertion upon finding record in the Calendar of State Papers of the period (documents not accessible to his predecessors and only then recently made available) that Samuel had been sent ahead to England prior to his father and was indeed there at that time.[35]

The accumulated evidence is certainly suggestive of forgery, but is it dispositive? Could there be another plausible explanation behind this diploma? I would like to suggest that its rejection as an official Oxford diploma does not inexorably lead to a verdict of forgery. By placing this diploma into the larger context of Jewish medical training and diplomas, as well as comparing Samuel’s diploma to other known medical diploma forgeries of the time, specifically for the universities of Padua and Oxford, we may be able to offer another alternative to criminality for one not known to be inclined to such behavior, not to mention being the son of a prominent Jewish rabbi and statesman. I endeavor at minimum, to prove reasonable doubt regarding the accusation of forgery.

Griffith’s Omission and the “Jewish” Diploma

Griffith correctly asserts that Samuel’s diploma is modeled after that of Padua. There is however, a key aspect of this supposed forgery that has previously gone unnoticed. What Griffith did not mention, nor was he likely aware, is that the diplomas issued to Jewish students in Padua often differed in a number of ways from the standard university issue. While there was no specific Jewish diploma template per se, as the standard diploma contained a number of Christian references, the diplomas of Jewish graduates invariably contain some combination of omissions or emendations to the standard text.

As part of our investigation into the diploma’s possible forgery, it is important to ascertain whether Samuel’s diploma is a copy of a standard Padua diploma or one of the Jewish variety. Below we list a few of the typical changes found in Padua diplomas of Jewish medical graduates of Samuel’s period, providing examples of each. We then compare them to Samuel’s diploma.

- The Headline of the Diploma

The most obvious change to the Jewish diploma meets the eye of the reader immediately upon viewing the document. The headline of the typical diploma reads, “In Christi Nomine Amen” (in the name of Christ, Amen), and it usually appears in larger decorative font, occasionally occupying an entire page.

William Harvey’s Medical Diploma (Padua 1602)

This would clearly have been objectionable to the Jewish student. The diplomas of the Jewish students were therefore usually emended to read, “In Dei Aeterni Nomine” (in the name of the eternal God), or some variation thereof.

Below are a number of emended diplomas of Jewish students:

Diploma of Isaac Hellen (Padua, 1649)[36]

Diploma of Emanuel Colli (Padua, 1682)[37]

- The Date

There are number of ways the year of the degree could appear on the typical diploma, and all of them include Christian reference. Examples include Anno Domini, Anno a Christi Nativitate, and Anno Christiano. Two typical examples are below.

Diploma of Giulio Antonio (1679)[38]

Diploma of John Wallace (around 1618)[39]

The date was unaltered for many Jewish diplomas

Diploma of Jacob Levi (Padua, 1684)[40]

Diploma of Isaac Hellen (Padua, 1649)

In some Jewish diplomas however, the Christian reference is omitted, and the date is listed as “currente anno,” current year.

Diploma of Moise Tilche (Padua, 1687)[41]

Diploma of Lazzaro De Mordis (Padua, 1699)[42]

The date alone is not a reliable indicator of the “Jewishness” of the diploma.

- The Location of the Graduation Ceremony

The graduation ceremony for the Catholic medical students was held in the Episcopal Palace and this was recorded in the diploma:

Diploma of Giulio Antonio (Padua, 1679)

The degrees of the Jewish students were not granted in the Episcopal Palace, but rather in non-ecclesiastical venues. As such, the words “Episcopali Palatio” are omitted, leaving the phrase “in loco solito examinu,” (in the usual place of examination).[43]

Diploma of Isaac Hellen (Padua, 1649)

This is the case in virtually all Jewish diplomas.

- Hebreus or Iudeus

There is one feature of the typical Jewish diploma that is not an emendation or omission, but rather an addition. With few exceptions, the Jewish students were identified as Hebreus or Iudeus. This was the convention in Padua for centuries and was found in other Italian universities as well.[43]

Diploma of Isaac Hellen (Padua, 1649)

Diploma of Emanuel Colli (Padua, 1682)

Diploma of Moise Tilche (Padua, 1687)

There are a few exceptions:

Diploma of Moysis Crespino (Padua, 1647)[45]

Notarized Copy of Diploma of Abraham Wallich (Padua, 1655)[46]

Abraham Wallich graduated Padua in 1655, the same year as Samuel’s diploma. His original diploma is not extant, though we have a notarized copy that he presented to the Jewish community of Frankfurt as proof of his credentials. In this copy, the identifiers of Hebreus or Iudeus do not appear. I suggest that “Iudeus” could have in fact appeared in his original diploma and was possibly omitted here by the copyist. As Wallich was a religious Jew applying to a Jewish institution, it would have been superfluous to add “Hebreus.”

- The Details of the Graduation Ceremony.

The standard Padua diploma also included a description of the graduation ceremony. This was not altered in the Jewish diplomas as the Jewish students participated in this ceremony, albeit with some changes. While the location may have been different, and perhaps the oath would have been tailored for the Jewish student, the core of the ceremony for the Jewish student otherwise remained the same. A remarkable pictorial testimony to this fact is the diploma of Moise di Pellegrino (AKA Moshe ben Gershon) Tilche, who graduated Padua in 1687.[47]

Underneath the portrait of the graduate is the illustration, represented with putti, of the features of the graduation ceremony of Padua.

This ceremony involved a golden ring, a wreath and a hat, known as a biretta (though not the four-cornered variety). The opening and closing of books as a representation of the transmission of knowledge was also a part of the ceremony.

Was Samuel’s Diploma modeled after a standard or “Jewish” Diploma from Padua?

In review of the Jewish diplomas from Padua of Samuel’s day, the headline was consistently altered, as was the location of the graduation. The typical Christian recording of the year of graduation was occasionally, though not uniformly altered. The majority of the Jewish graduates, with few exceptions, were identified as either Iudeus or Hebreus.

Which of these additions, omissions or alterations appear in Samuel’s diploma?

- The Headline

In his article republishing the existing material on Samuel’s diploma, Neubauer writes, “in order to make the documents concerning this degree accessible to the Anglo-Jewish public, I shall reproduce here the Latin diploma line by line (Neubauer’s emphasis) as given by Koenen.” The text of the diploma he provides begins as follows:

In the original publication by Koenen however, the diploma begins with a short phrase:

Neubauer omitted the introductory words, “In Nomine Dei, Amen,” perhaps assuming they were not part of the diploma, or simply noncontributory to the text. In fact, these four words are crucial in identifying the nature of Samuel’s diploma and reflect one of the major differences found virtually ubiquitously in the Jewish diplomas of Padua.

- Date

A typical Christian date is used.

- Location of Graduation

The location of the ceremony is given as the Academy of Oxford.

- Hebreus or Iudeus

The identifier Hebreus or Iudeus is not found in Samuel’s diploma.

The headline in Samuel’s diploma is clearly consistent with the Jewish form of diploma. The date is of a Christian format, Anno Christiano, and the location is listed simply as Oxford with no reference to an ecclesiastical venue.

The identifier “Hebreus” is conspicuously absent. To be sure, there were certainly other examples where this was true. However, the omission in Samuel’s case is noteworthy, as his own father, Menasseh, self-identified as Medicus Hebreus, as did other Jewish physicians in Amsterdam, such as Ephraim Bueno. Surely the son would have adopted the title of the father.

In sum, the headline of Samuel’s diploma, a crucial element in determining its style, conforms to the Jewish Padua diploma, as does the venue for the degree, which is non-ecclesiastic. While the date retains the Christian reference, this is non-contributory. Samuel’s diploma does however omit the typical Jewish identifier of Hebreus, a title specifically used by his own father, a fact that begs explanation.

Other Medical Diploma Forgeries of the Seventeenth Century

If Samuel’s diploma were indeed a forgery, it would be the only known case of a forged medical diploma by a Jewish physician in the pre-Modern era. To be sure, there have been numerous forgeries of diplomas, including the medical variety, throughout history. Below we discuss two forgeries of the same historical period as Samuel and purported to be from the two very institutions with which Samuel’s diploma is associated. These may shed light on our forgery discussion.

A Forged Medical Diploma from Padua 1628

The diploma of John Wallace sat in the Royal College of Physicians for centuries, assumed to be genuine. It was only recently that Dr. Fabrizio Bigotti took a closer look at the diploma, revealing that it was a clear forgery.[48] Below you see the latinized name of Wallace clearly written in a different pen and different hand than that of the original diploma.

The year of graduation, 1628, was also altered.

The date was proven to be fake, as the authentic signatures at the end of the diploma include Fabrici d’Acquapendente and Adrian van de Spiegel, both of whom had died by 1628. The true date is assumed to be around 1618.

In this case of forgery, Wallace procured an existing diploma and replaced the name and date with his own. There is apparently no record of his medical practice, so it is unclear if his forgery was successful. Perhaps he forged this diploma with intent to present to Oxford for incorporation. I do not know if the RCP checked the Oxford Register of Congregation for the relevant years.[49]

The Frankland Forgery of an Oxford Diploma[50]

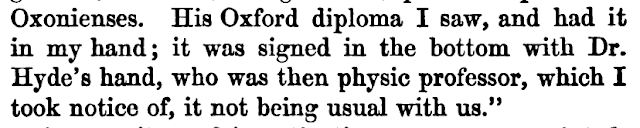

In the diary entry for Anthony Wood, Oxford antiquary, for November 15, 1677, we find the following:[51]

Frankland first presented his false credentials in 1667.[52] He was apparently a haughty and disagreeable man disliked by his colleagues at the college. It was his juniors who raised suspicion about his credentials and privately inquired of Dr. Hyde, King’s Professor of Physic, as well as the registrar, to verify his documents. The forgery was confirmed by Oxford in November 1677,[53] when it was determined that Frankland was not listed in the Medical School Register and that he had forged the university seal.[54] Furthermore, Frankland defrauded Cambridge University, which granted him a medical degree solely on the basis of his previously obtained Oxford diploma. Frankland not only forged the university seal of Oxford, which was an integral part of the official document, he seems to have added an element to the diploma which was a tip off as to its forgery. Dr. Brady of Cambridge reported:[55]

This exact issue was also identified by Griffith as one of the elements of Samuel’s diploma that deviated from Oxford protocols. Of course, with Samuel’s diploma, this was one of many deviations from Oxford’s template; for Frankland, this was more essential in identifying the forgery.

These two forgeries from Samuel’s period, and from the very institutions associated with his diploma are instructive. If Samuel was truly a forger, could or should he have pursued the methods of Wallace or Frankland?

A Padua Diploma Forgery ala Wallace

Forging a genuine Padua diploma would have been more challenging than one from Oxford for a number of reasons, both technical and cultural. While objectively few Jewish students attended the University of Padua Medical School,[56] it was the main address for Jewish students wishing to obtain a university medical degree. While far from Amsterdam, the Jews of Europe were all connected. In addition, Amsterdam was a hub of Jewish printing and a number of works by Italian authors were printed there. A forged medical diploma could possibly have been detected by Italian visitors. It would have been risky.

From a technical perspective, the Padua diploma, in Italian Renaissance fashion, was copiously illustrated and meticulously calligraphed, often including a portrait of the graduate. A number of these diplomas are extant in libraries and private collections.[57] It would have been exceedingly difficult to replicate the diploma itself, not to mention that it was typically bound in a gilded leather binding with official wax seals attached by thread.

Picture Courtesy of Professor Fabrizio Bigotti

All these accoutrements would have made the endeavor of forgery prohibitive from the outset.

There could have been another option for a Padua diploma forgery. Abraham Wallach had a notarized copy of his 1655 Padua diploma made for his job application as a community physician in Frankfurt.[58]

Beginning of the copy of the diploma:

Notarization of the diploma:

Perhaps Samuel could have created a similar “notarized” copy, which would not have required the artistry or associated binding and seals. This option would likely not have sufficed for Samuel, who as the “graduate,” would have been expected to possess and present the original.

Could Samuel have obtained an existing Padua diploma and simply replaced the name of the graduate with his own, as Wallace had done? This would certainly have been easier than forging the diploma de novo. However, recall that the Padua diplomas of the Jewish students had some alterations, the most obvious one being the headline change from In Christi Nomine to In Dei Aeterne Nomine, not to mention other more subtle, less noticeable changes. Samuel would have had to procure an old diploma that previously belonged to a Jewish student, an impossible task.

An Oxford Diploma ala Frankland

Should Samuel have created a diploma more in line with the actual Oxford model, as Frankland, whose forged university seal and diploma were sufficient to fool even the Royal College of Physicians and Cambridge University? Had he produced a Frankland-esque diploma no one would have suspected otherwise, as no Jew had ever obtained or presented an Oxford diploma before. While this could have been an ideal forgery,[59] I suggest below why this may not have served Samuel’s needs.

The Medical Training and Practice of Samuel ben Menasseh

Irrespective of the veracity of his diploma, Samuel appears to have been a practicing physician. Samuel is listed as a physician by both Steinschneider[60] and Koren,[61] each of whom provides additional references. He is also listed in an early twentieth century work among a group of exceptionally prominent Jewish physicians across the ages.[62] Moreover, his tombstone identifies him as a physician. To my knowledge we do not have any specific account of his clinical practice.

As we have no direct evidence as to how Samuel trained in medicine, we can only surmise based on the general climate of Jewish medical training at the time, coupled with whatever fragmentary evidence we have of Samuel’s personal medical exposure.

Samuel had personal exposure to both the apprenticeship and university pathways of medical training. His father most likely obtained his education through the apprenticeship pathway. Samuel certainly could have learned the medical art from his father Menasseh, though the biographies of Menasseh reveal that he had little time, if any, for the practice of medicine. It would have been difficult for Samuel to acquire comprehensive medical knowledge without prolonged extensive clinical exposure, something his father could not provide.

Though Menasseh himself may not have had the time to mentor his son, he could have delegated the task to one of his physician colleagues.[63] Ephraim Bueno, for example, was a prominent physician in Amsterdam with whom Menasseh had a relationship.[64] Bueno supported Menasseh’s first publication.[65] They also both shared the distinction of having their portraits drawn by Rembrandt.[66] Perhaps Samuel apprenticed with, or at the very least, was inspired by Bueno.

Had he desired, Samuel could have obtained a formal university medical degree. In the early part of the seventeenth century, this would only have been possible in Italy, and primarily at the University of Padua. Traveling to Padua, however, would entail leaving the family and other potential hardships, such as the language barrier. Fortunately, beginning in the mid-century universities in the Netherlands (primarily Leiden), following in the footsteps of Padua, began opening their doors to Jewish medical students for the first time.[67] In fact, Samuel’s cousin Josephus Abarbanel, who also lived in Amsterdam, graduated from the University of Leiden on June 2, 1655, just a few weeks after Samuel received his Oxford diploma.[68]

Which option/pathway did Samuel choose? Though his diploma is Padua-esque, there is no record of Samuel attending the University of Padua. There is also no record of his attendance or graduation from any school in the Netherlands.

Samuel certainly would not have attended the University of Oxford as a student. Professing Jews were not allowed there. Moreover, it would also have required his presence in England for a prolonged period, which, by all accounts was not the case. Roth writes regarding the likelihood of Samuel obtaining an Oxford degree, “it was as difficult for a Jew to be graduated from it (Oxford) as it would have been for an anthropoid ape.”[69] This unwelcoming climate for the Jews persisted even long after the return of the Jews to England.[70] In fact, in Herman Adler’s lecture on the Jews of England in the late nineteenth century, he comments on the medical degree of Samuel, which he assumed to be authentic: “This fact (granting a medical diploma to the Jew Samuel ben Israel) would seem to show that the university was more enlightened in the year 1655 than it is in 1870.”[71]

Samuel’s “For Jewry” Diploma

I suggest that Samuel trained primarily through the apprenticeship pathway but requested and received university acknowledgement or imprimatur of his medical education and knowledge. The diploma was thus an affirmation of Samuel’s expertise attested to by members of the Oxford faculty. As opposed to today, when a student must attend a certain number of years in a university as a prerequisite to obtaining a degree, universities often gave exams and imprimatur to those who studied elsewhere, either formally or not, but passed the required examination demonstrating the required knowledge and competence. This could explain the unusual nature of the diploma he procured from Oxford.

While many Jewish physicians in this period practiced freely without university education or diplomas, there may have been an additional impetus for Samuel to procure this affirmation from Oxford. The Dutch were generally known for their tolerance, but this apparently did not extend to the Jews and the practice of medicine. According to historians, “Although Jews with foreign degrees were permitted to engage in medicine as general practitioners, tolerance was not extended to tertiary education.”[72] Thus, even though Samuel may have been qualified to practice by virtue of his apprenticeship, and could have practiced freely in other European countries, his practice in the Netherlands would have been limited without a foreign degree.[73]

Do the existing facts and diploma support this theory?

The Signatories

The two signatories on Samuel’s diploma were Dr. John Owen and Dr. Clayton at Oxford. Owen was a friend of Cromwell and Vice Chancellor of the University at that time. Thomas Clayton was Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford from 1647 to 1665. These were not fictional characters, and if one were to obtain an affirmation of medical knowledge or education, these would be the perfectly appropriate people to attest to such a document. Given Menasseh’s connections, it is not inconceivable that he utilized his influence to arrange for his son’s exams, or that they acceded to Samuel’s request out of deference to Menasseh.

The Absence from the Oxford Register

Griffith highlights the fact that Samuel’s degree is not found in the Oxford Register. Indeed, no professing Jews were listed in the register at Oxford at that time. According to our theory, this absence from the Register is no proof of forgery. There was not the slightest thought of entering this exchange into the official university Register, as not only did it not meet the standard protocols, the recipient was also of the Jewish faith and expressly precluded from such a privilege. Samuel may have assured the examiners that he had no intention of practicing in the United Kingdom, a fact that would have made it easier for them to feel comfortable affixing their names to the document.

Likelihood of Exposure

If indeed Samuel were prone to deceit, what is the likelihood his rouse would have been discovered? His father would certainly have realized.[74] The very purpose of Samuel’s trip was to pave the path for his father’s visit. Samuel was thus expecting his father to later visit England and likely interact with the very same people he did. Indeed, Menasseh appears to have visited Oxford.[75] Surely Samuel’s diploma would have come up in conversation, if only peripherally. This alone could have served as a deterrent for forgery. Additionally, John Owen, a signatory on the diploma, was a close friend of Cromwell’s, and a forgery could have been revealed through this avenue. If one were to arbitrarily choose Oxford faculty for a fake diploma, better not to choose someone whose trail could ultimately lead to disclosure.

A forgery would have been suspected, if not revealed, from another source. Samuel’s cousin Joseph Abarbanel completed his medical training in Leiden at the very same time as Samuel’s diploma was issued, and also lived in Amsterdam. He surely would have been suspicious if Samuel suddenly started practicing medicine after a forged Oxford diploma emerged de novo and appeared, metaphorically, framed on Samuel’s office wall.

The Text of the Diploma- An Oxford-Padua Synthesis ala Samuel ben Menasseh

Working with our new theory, which type of diploma would Samuel have procured or designed had he genuinely presented to Oxford and successfully passed oral exams from the university faculty? This would not have been an official, formal process, but rather a unique private opportunity to confirm his medical expertise with the Oxford faculty. As this was a personalized, non-institutional diploma, the examiners would not have much cared or paid attention as to the diploma’s format and could have left the document particulars to Samuel.

I suggest, therefore, that Samuel designed the document in a way that would best serve his needs and would be well-received by his Jewish clientele in the Netherlands. A brief informal text with attestation from the Oxford professors would have been unfamiliar and unimpressive to his Jewish patients.[76] Virtually the only diploma a Jewish university-trained physician would have possessed in this period is a diploma from the University of Padua.[77] He therefore utilized the familiar Padua template, as awkward and inconsistent with Oxford’s typical diploma it may have been. Furthermore, he made sure to use the emended headline and non-ecclesiastic venue consistent with the “Jewish” diploma.

Why did Samuel not include the term “Hebreus,” which would surely have been familiar to the Jewish viewers of the diploma, not to mention following in the path of his father, who was known as “Medicus Hebraeus?” It is possible that Samuel would have specifically omitted this title given the history of the degree-granting institution. Professing Jews were categorically precluded from attending or graduating Oxford. While the signators may not have paid close attention to the details of the diploma, the word Hebreus after Samuel’s name would likely have caught their eye, especially as it appears adjacent to the graduate’s name.

There are numerous elements in the diploma that were simply untrue. For example, included is a description of the graduation, as cited by Graetz. Did Samuel actually participate in a formal graduation from Oxford? Whether Samuel obtained a genuine diploma of some sort from Oxford can be debated, but there is no doubt that as a professing Jew in England at this time he would never have participated in any formal graduation ceremony. Samuel may have disregarded these details favoring style over substance in order to achieve his objective. The signators would likely not have bothered to analyze the text.

Not a single Jew would have known the difference, let alone read the Latin document, nor would they have questioned further.[78] They would have seen a document that appeared in style and largely in substance similar to the diplomas they had seen previously. Samuel’s father would have been proud of his son’s accomplishment, as would his cousin Josephus Abrabanel, who later graduated from Leiden. Menasseh could also have personally thanked Drs. Owens and Clayton for their kindness when he visited Oxford a short time later. If this construct is true then Samuel’s diploma would not have been a forgery, but rather “for Jewry,” being designed intentionally with the Jewish community in mind, and in the context of Jewish medical history.

Postscript

Whether forged on not, Samuel sadly had but little time to utilize the Oxford diploma dated May 1655. Later that month he returned to Amsterdam, diploma in hand, to persuade his father to go to England and personally lay his case before Cromwell. Two years later, Manasseh ben Israel arrived in London, accompanied by Samuel. Samuel tragically died during their stay. In accordance with Samuel’s dying wish, Manasseh ben Israel conveyed his son’s corpse back to Holland where he was buried on 2 Tishrei, 5418. Below is a picture of the grave of Samuel ben Israel in the Middleburg Cemetery, 1912, shortly after it was renovated.[79]

Here is a picture of the grave and tombstone today:[80]

His medical identity is forever enshrined on his tombstone, where he is referred to as “Doctor Semuel.”[81]

Roth writes, “It seems obvious that the honorific description (on the tombstone) has its basis the supposed Oxford degree.”[82] I beg to differ. Many Jewish physicians were trained through apprenticeship and never obtained university degrees, Samuel’s own father being a case in point, and they were nonetheless known as physicians. I believe Samuel could have been such a physician.

Menasseh himself died shortly thereafter on Nov. 20, 1657, before reaching his home at Middelburg, Zealand.

Which account is closer to the truth? Was Samuel an ambitious and accomplished student of medicine, honestly earning some form of an Oxford diploma, perhaps not unlike Friedberg’s description at the beginning of this article; or was he an unabashed imposter possessing no medical training, brazenly forging a medical diploma, and practicing medicine without proper training? Historians have been quick to condemn Samuel, though they have neglected to incorporate the history of Jewish medical training into their analyses. Ultimately, I suggest that the truth lies in the chasm between these two polar extremes. Closer to which one? I leave to the reader to decide. At the very minimum I believe we have provided enough evidence to at least create reasonable doubt as to whether Samuel the son of the right honorable Menasseh ben Israel committed willful forgery of his medical diploma.

[1] Also known as Samuel Abravanel Soeyro. See Moritz Steinschneider “Judische Aertze,” Zeitschrift fur Hebraeische Bibliographie 18: 1-3 (January-June, 1915), p. 45, n. 1923. Abravanel is taken from his mother’s family and Soeyro from his father’s family. Both names have multiple variant spellings.

[2] Cecil Roth, A Life of Menasseh Ben Israel: Rabbi, Printer, and Diplomat (Jewish Publication Society, 1945); Jeremy Nadler, Menasseh ben Israel: Rabbi of Amsterdam (Yale University Press, 2018). See also the wonderful online exhibit, “Menasseh ben Israel, rabbi, scholar, philosopher, diplomat and Hebrew printer, 1604-1657,” curated by Dr. Eva Frojmovic of the University of Leeds.

[3] For a history of Jewish physicians as printers, see J. O. Leibowitz, “Jewish Physicians Active as Printers,” (Hebrew) Harofe Haivri Hebrew Medical Journal 1 (1952), 112-120; Hindle Hes, “The Van Embden Family as Physicians and Printers in Amsterdam,” (Hebrew) Koroth 6:11-12 (August, 1975), 719-723.

[4] https://benyehuda.org/read/3230#fn:173, Zichronot LiBeit David vol 4 (Achiasaf Publications, Warsaw, 1897).

[5] Friedberg himself references the mention of the diploma in Meyer Kayserling’s The Life and Labours of Menasseh Ben Israel (London, 1877). 63 and 92, n. 241.

[6] Friedenwald mentions Menasseh, but as opposed to his other entries, adds justification for his inclusion in his work: “He is included in this list because several of his works bear his name with the title Medicus Hebraeus,” as well as his identifying as a Doctor of Physick in his letter to the Lord Protector. See Harry Friedenwald, The Jews and Medicine vol. 2 (Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore, 1944), 739. Menassah is also is listed in Koren under the spelling Manasseh ben Israel. See Nathan Koren, Jewish Physicians: A Biographical Index (Israel Universities Press: Jerusalem, 1973), 89.

[7] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 109.

[8] While Bueno is famous for his portrait drawn by Rembrandt, his portrait was also drawn later in life by another Dutch artist, Jan Lievens. The description underneath the painting, Dor Ephraim Bonus Medicus Hebraeus, found in the collection of Joods Historisch Museum Amsterdam, can be seen below:

[9] This work is not extant. See Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 314, n. 17.

[10] I. M. Librach, “Medicine and Menasseh Ben Israel,” Medical History 4:3 (July, 1960), 256-258 discusses Menasseh’s connection to physicians. Librach suggests that the close relationship between religion and medicine among the Jews has led some historians, notably Henry Milman (1863) to regard Menasseh as a physician as well as a rabbi. For further reference to Menasseh’s physician friends see Ernestine G.E. Van Der Wall, “Petrus Serrarius and Menasseh ben Israel: Christian Millenarianism and Jewish Messianism in Seventeenth Century Amsterdam,” in Yosef Kaplan, et. al., eds., Menasseh Ben Israel and His World (E. J. Brill: Leiden, 1989), 172; George M. Weisz and William Albury, “Rembrandt’s Jewish Physician- Dr. Ephraim Beuno (1599-1665): A Brief Medical History,” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 4:2 (April, 2013).

[11] Van Der Wall, op. cit., 165.

[12] Personal communication with Hans Froon of the Central Medical Library in Groningen (December, 2020).

[13] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 42, 109, 314, 341

[14] This picture of the epitaph appears in Cecil Roth, “New Light on the Resettlement,” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society 11 (1924-1927), facing p. 118.

[15] For articles on the training of Jewish medical students, see Harry Friedenwald, “The Jewish Medical Student of Former Days,” Menorah Journal 7:1 (February, 1921), 52-62; Cecil Roth, “The Medieval University and the Jew,” Menorah Journal 19:2 (November-December, 1930), 128-141; Idem, “The Qualification of Jewish Physicians in the Middle Ages,” Speculum 28 (1953), 834-843; Joseph Shatzmiller, “On Becoming a Jewish Doctor in the High Middle Ages,” Sefarad 43 (1983), 239-249. Idem, Jews, Medicine and Medieval Society (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1994), esp. 14-27; John Efron, “The Emergence of the Medieval Jewish Physician,” in his Medicine and the German Jews: A History (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2001), 13-33; Edward Reichman, “From Maimonides the Physician to the Physician at Maimonides Medical Center: The Training of the Jewish Medical Student throughout the Ages,” Verapo Yerape: The Journal of Torah and Medicine of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine 3 (2011), 1-25; Nimrod Zinger, Ba’alei haShem vihaRofeh (Haifa University, 2017), 242-251.

[16] The University of Padua was the first to formally allow admission of Jews to its medical school.

[17] It is possible that there were titles that distinguished between university and non-university trained physicians, such as rofeh mumheh, but this requires further study.

[18] H. J. Koenen, Geschiedenis der Joden in Nederland (Utrecht, 1843), 440-444.

[19] Gabriel Isaac Polak, Seerith Jisrael: Lotgevallen der Joden in alle werelddeelen van af de verwoesting des tweeden tempels tot het jaar 1770 (Amsterdam, 1855), 549.

[20] Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews vol. 5 (Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia, 1956), 38.

[21] Herman Nathan Adler clearly follows Graetz in his, The Jews of England A Lecture (Longmans, Green and Co.: London, 1870), 23.

[22] Since the initial publication of Griffith’s letter was in an obscure inaccessible journal, both the transcription of the diploma as well as Griffith’s letter were later republished. All the documents and articles are reproduced in Rev. Dr. Adler, “A Homage to Menasseh ben Israel,” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 1 (1893-1894), 25-54, esp. 48-54. This explains why some scholars were unaware of Griffith’s conclusions until years later. For additional comments and analysis, see Cecil Roth, A Life of Menasseh Ben Israel (Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia, 1934), 221-222 and 337-339; Idem, “The Jews in English Universities,” Miscellanies of the Jewish Historical Society of England 4 (1942), 102-115, esp. 105, n. 14.

[23] Griffith lists fifteen differences in the form of the diploma from that of Oxford.

[24] Statutes of the University of Oxford codified in the year 1636, under the authority of Archbp. Laud, Chancellor of the University, with an introduction on the history of the Laudian Code by C.L. Shadwell, ed. by John Griffiths, 1888. See p. 126. For the study of medicine at Oxford in the seventeenth century see chapter by Robert G Frank Jr. entitled “Medicine” in The History of the University of Oxford, volume IV: Seventeenth Century Oxford (ed. N Tyacke, Clarendon Press, 1997). For a more general study of the period, see Phyllis Allen, “Medical Education in 17th Century England” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1:1 (January 1, 1946), 115-143.

[25] G. R. M. Ward, Oxford University Statutes (1845), 53-54, 117-118, 128-131.

[26] Oxford’s Register of Congregation during this period contains numerous examples of Padua students applying for incorporation.

[27] Alphei Menasheh Catologus of J. S. Da Silva Rosa (Portugeesch Israelietische Seminarium: Amsterdam, 1927), 25, no. V. lists a picture of the first and last pages of the diploma in the possession of the Montezinos Library.

[28] Roth did not mention if he possessed copies of the entire text of the diploma.

[29] I thank Heide Warncke, Curator of the Ets Haim Library for her assistance.

[30] I thank Rachel Boertjens, Curator of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana for her assistance.

[31] I thank Eva Frojmovic and the staff of the Roth Collection at University of Leeds for their assistance. The cataloguing of the Roth Collection is an ongoing process and there is a fair amount of material still uncatalogued. I am hopeful the copies of the diploma will one day surface there.

[32] In the interest of full disclosure, I recently wrote an article entitled, “Confessions of a Would-be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuvia Ha-Rofeh) and Other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua.” I am not however personally inclined to forgery. I would be happy to send the reader a copy of my medical diploma upon request, once I am able to locate it.

[33] David S. Katz, Philo-Semitism and the Readmission of the Jews to England, 1603-1655 (Oxford University Press, 1982), 197.

[34] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 338-339

[35] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 338-339.

[36] Germanisches Nationalmuseum, reference no. HA, Pergamenturkunden, Or. Perg. 1649 Juli 09.

[37] A copy of the full diploma is accessible through the Magnes Online Collection, http://magnesalm.org (accessed January 5, 2021).

[38] See G. Baldissin Molli, L. Sitran Rea, and E. Veronese Ceseracciu, Diplomi di Laurea all’Università di Padova (1504–1806) (Padova: Università degli studi di Padova, 1998), diploma C21, p. 151.

[39] See below for further discussion of this diploma, which is a forgery. The body of the diploma, including the relevant phrase cited here, is original and dates to around 1618.

[40] This diploma is housed in the Umberto Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem. See http://www.museumsinisrael.gov.il/en/items/Pages/ItemCard.aspx?IdItem=ICMS-EIT-0076. The museum website provides a description of the diploma and a picture of the outer cover. I thank Dr. Andreina Contessa, former Chief Curator of the U. Nahon Museum, for kindly furnishing me with pictures of the entire diploma. I thank Sharon Liberman Mintz for bringing this diploma to my attention.

[41] The diploma is in the William Gross Collection and is available for viewing at the website of the National Library of Israel, system number 990036743400205171 (accessed January 3, 2021). I thank Sharon Liberman Mintz for bringing this diploma to my attention.

[42] NLI, system number 990035370060205171.

[43] Of course it was not “the usual place of examination,” but this text allowed for the least amount of deviation from the diploma template.

[44] See, for example, the diploma of Chananya Modigliani from Siena, 1628 in the Jewish Theological Seminary Library, MS 8519.

[45] NLI, system number 990034232880205171.

[46] Stadt Frankfurt am Main, Altes Archiv – Städtische Überlieferung bis 1868, Medicinalia, Akten, Nr. 250 (fol. 51-52v).

[47] For an expansive discussion on the diplomas of Jewish medical students from the University of Padua, see Edward Reichman, “Confessions of a Would-be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuvia Ha-Rofeh) and Other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,” in Kenneth Collins and Samuel Kottek, eds., Ma’ase Tuviya (Venice, 1708): Tuviya Cohen on Medicine and Science (Jerusalem: Muriel and Philip Berman Medical Library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2019), in press.

[48] Pamela Forde, “Power and Beauty: Fakes and Forgeries,” (December 11, 2015) Royal College of Physicians Museum. I thank Dr. Bigotti of Centre for the Study of Medicine and the Body in the Renaissance, Domus Comeliana Pisa (Italy) for providing me the images of this diploma.

[49] I do not have access to the relevant years.

[50] For the most expansive discussion of the Frankland affair see William Munk, The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London vol 1, 1518-1700 (Longman: London, 1861), 358ff.

[51] Andrew Clark, The Life and Times of Anthony Wood, Antiquary, of Oxford, 1632-1695, Described by Himself vol. 2 (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1892), 392-393.

[52] Munk, op. cit., 359.

[53] Munk, op. cit., 360.

[54] Munk, op. cit., 363.

[55] Munk, op. cit., 362.

[56] For a list of the Jewish students attending the University of Padua during Samuel’s time, see Abdelkader Modena and Edgardo Morpurgo, Medici E Chirurghi Ebrei Dottorati E Licenziati Nell Universita Di Padova dal 1617 al 1816 (Bologna, 1967). This list has been supplemented over the years, but the overall numbers are not significantly different.

[57] For a collection of diplomas from the University of Padua, see G. Baldissin Molli, L. Sitran Rea, and E. Veronese Ceseracciu, Diplomi di Laurea all’Università di Padova (1504–1806) (Padova: Università degli studi di Padova, 1998). Only a very small percentage of the diplomas in this book are from the medical school. For examples of diplomas from other Italian universities, see Honor et Meritus: Diplomi di Laurea dal XV al XX Secolo, ed. F. Farina and S. Pivato (Rimini: Panozzo Editore, 2005), a catalogue of an exhibition held in 2006 to mark the 500th anniversary of the founding of the University of Urbino.

[58] For more on Abraham Wallich and other physician family members of the Wallich family, see, Edward Reichman, “The Medical Training of Dr. Isaac Wallich: A Thrice-Told Tale in Leiden (1675), Padua (1683) and Halle (1703),” Hakirah, in press.

[59] It is possible that Samuel was simply unaware of the composition and protocols of the Oxford degree, as he would not have had occasion to see one. Perhaps he was attempting to mimic a genuine Oxford diploma, but just erroneously assumed it was similar to that of Padua.

[60] Moritz Steinschneider “Judische Aertze,” Zeitschrift fur Hebraeische Bibliographie 18: 1-3 (January-June, 1915), p. 45, n. 1923. He is listed as “Samuel (b. Menasseh) b. Israel Abravanel-Soeyro (Suerus).”

[61] Nathan Koren, Jewish Physicians: A Biographical Index (Israel Universities Press: Jerusalem, 1973), 126. He is listed as “Soeiro Samuel Abrabanel of Amsterdam, son of Menasseh ben Israel, grad. in Oxford.”

[62] Dov Bear Turis, Shiva Kokhvei Lekhet (Warsaw, 5687), 16. Menasseh is not mentioned in this list.

[63] I thank Heidi Warncke for this suggestion.

[64] On Bueno, see, for example, George Weisz and William Albury, “Rembrandt’s Jewish Physician Dr. Ephraim Beuno (1599-1665): A Brief Medical History,” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 4:2 (April 2013), 1-4.

[65] Sefer Penei Rabah (Amsterdam, 1628)

[66] See Steven Nadler, Rembrandt’s Jews (University of Chicago, 2003). Nadler discusses the debate as to whether Rembrandt actually painted a portrait of Menasseh ben Israel. In either case, both Bueno and Menasseh were well acquainted with Rembrandt, who lived in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam.

[67] Hindle S. Hes, Jewish Physicians in the Netherlands (Van Gorcum, Assen, 1980); Kenneth Collins, “Jewish Medical Students and Graduates at the Universities of Padua and Leiden: 1617-1740,” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 4:1 (January, 2013), 1-8; M. Komorowski, Bio-bibliographisches Verzeichnis jüdischer Doktoren im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert (K. G. Saur Verlag: Munchen, 1991). Komorowski, p. 33, lists the dissertations of a handful of Jewish graduates of Netherland universities prior to 1650.

[68] Hes, op. cit., 3, Komorowski, op. cit., 33. Josephus was Menasseh’s first cousin. His dissertation was entitled “De Phthisi.” Joseph’s father, Jonah, joined Bueno in supporting Menasseh ben Israel’s book, Penei Rabah. Joseph Abarbanel was later excommunicated by the Sephardic community for rejecting the prohibition against buying poultry from Ashkenazi Jews. See Yosef Kaplan, An Alternative Path to Modernity: The Sephardic Diaspora in Western Europe (Brill, 2000), 136.

[69] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 221. The only Jews who would have attended Oxcam at this time would have been converts to Christianity, though Jews from birth. See Cecil Roth, “The Jews in English Universities,” Miscellanies of the Jewish Historical Society of England 4 (1942), 102-115. This is why Roth comments that the diploma is a “not too skillful forgery of an inherently improbable doctorate.” Roth adds that into the eighteenth century the climate for Jews at the universities in England was so unwelcoming that even native English Jews travelled abroad to Germany, Netherlands, Scotland, or Italy to obtain their medical degrees.

[70] Until the 1800’s Jews could not graduate Oxford or Cambridge unless they professed their belief in Christianity. See Joseph L. Cohen, “The Jewish Student at Oxford and Cambridge,” Menora Journal 3 (1917), 16-23.

[71] Graetz, op. cit., also wrote, “It was no insignificant circumstance that this honor should be conferred upon a Jew by a university strictly Christian in conduct.”

[72] Weisz and Albury, op. cit.

[73] Admittedly, this is also a strong motivation for forgery, but I shall leave this line of argument for the prosecution.

[74] Roth comments that, “it is impossible to believe that Menasseh ben Israel can have been a party to the deception. One can only imagine that he was a victim of it.”

[75] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 251-252.

[76] It likely would not have sufficed for the Dutch government either.

[77] While the universities of the Netherlands had begun issuing diplomas to Jewish students, the Padua diploma would still have been far more common.

[78] Would the Dutch government have accepted such a document? The record is silent on this question.

[79] https://www.zeeuwseankers.nl/verhaal/portugese-joden-in-zeeland. In 1911/1912 English Jews visited Middelburg and found the grave in decay. They told the city that a very important person is buried there who played a vital role (together with his father of course) in the readmission of the Jews in England. The gravestone was renovated, and possibly raised at that stage, and a chain was put around it. I thank Heide Warncke, Curator of the Ets Haim Library in Amsterdam for the information and references.

[80] https://www.omroepzeeland.nl/nieuws/100031/Joodse-begraafplaatsen-verstopt-in-Middelburg.

[81] Ephraim Bueno is also identified as a physician on his tombstone. Picture in Weisz and Albury, op. cit.

On the tombstone on the left, the end of the second line reads, Dor (doctor).

Joseph Abarbanel, while identified in the Ouderkerk Cemetery record as a physician, is not identified as such on his tombstone (inscription at the bottom of the document).

I thank Heide Warnicke for her assistance with the translation of these tombstones.

[83] Roth, op. cit., Menasseh, 139. Nadler echoes the same sentiment, adding that no one suspected the ruse in his lifetime as his gravestone identifies him as a doctor. See Nadler, op. cit., 263.

2 thoughts on “The “Doctored” Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menasseh Ben Israel: Forgery or “For Jewry”?”

An exemplary piece! Hugely enjoyable, as well! Thank you.

“Without the actual document, it is impossible to definitively comment on its veracity. Access to the original would allow analysis of the ink and paper for dating”

How would that help? Any forgery would not doubt be a contemporary forgery. Which would have the same paper and ink etc as all other documents from that time period.