In Praise of Ephemera: A Picture Postcard from Vilna Reveals its Secrets More than One Hundred Years after its Original Publication

In Praise of Ephemera:

A Picture Postcard from Vilna Reveals its Secrets

More than One Hundred Years after its Original Publication*

by Shnayer Leiman

I belong to a small group of inveterate collectors of Jewish ephemera. We collect artifacts that many others consider of little or no significance, such as postage stamps; coins and medallions; old posters, broadsides, and newspaper clippings; outdated New Years cards; wine-stained Passover Haggadot; Jewish ornaments, objects (e.g., Chanukkah dreidels) and artwork of a previous generation; photographs and postcards; and the like. The items we collect – all of Jewish interest – take up much space in our homes; they can also be costly at times. Often, we end up paying much more for an item than it is really worth, especially if it completes a set. Collectors of ephemera suffer from a disease that has no known remedy. The only respite we have from the disease is when we write scholarly essays about what we have collected, for – as I know from experience – it is not possible to write scholarly essays and actively collect ephemera at the same time.

The Picture Postcard.

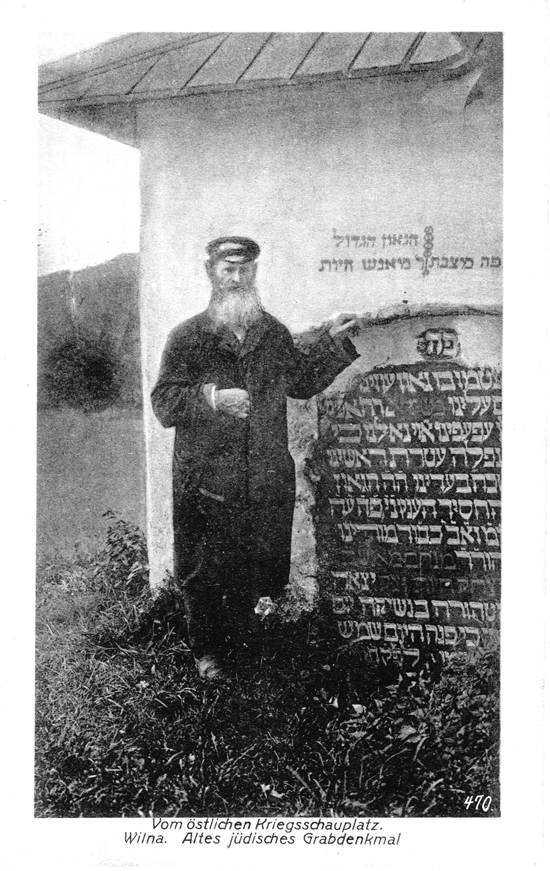

Several years ago, I acquired the following postcard. It measures 5½ inches by 3½ inches, a standard size for its time. It is a mint copy, meaning that no message was penned on its back and it was never mailed. Thus, I cannot date the postcard by a recorded date or postmark on its reverse side (but see below). We present the obverse and the reverse of the postcard for the benefit of the reader:

Obverse. The obverse presents a black and white photograph, also standard for its time. It features a tombstone with a Hebrew inscription; a mausoleum behind the tombstone, with a brief Hebrew inscription; and what appears to be a cemetery attendant, with his hand atop the tombstone. Most important, it contains a German heading under the photograph, which reads in translation: “From the Eastern Front of the Theater of War, Wilna, An Old Jewish Tombstone [with Inscription].”

Reverse. The reverse prints the name of the publishing company that produced the postcard: “The Brothers Hochland in Koenigsberg, Prussia.”

Historical Context.

In terms of historical context, the information provided by the postcard (a German heading; Vilna is defined as the eastern front of the theater of war; the postcard was produced in Koenigsberg) can lead to only one conclusion, namely that the postcard was produced on behalf of the German troops that had occupied, and dominated, Vilna during World War I. German troops occupied Vilna on September 18, 1915 and remained in Vilna until the collapse of the Kaiser’s army on the western front, which forced the withdrawal of all German troops in foreign countries at the very end of 1918. Thus, our photograph was taken, and the postcard was produced, during the period just described. Its Sitz im Leben was the need for soldiers to send brief messages back home in an approved format. The ancient sites of the occupied city made for an attractive postcard. (This may have been especially true for Jewish soldiers serving in the German army.)

Due to a wonderful coincidence, a distinguished scholar of Yiddish and a dear colleague, Professor Dovid Katz, recently published a copy of the very same postcard we publish here.[1] Unlike my copy, his copy includes on the reverse side a dated message penned by the German soldier who mailed it, as well as a dated postmark. The message was written on December 3, 1917 and postmarked the next day, on December 4. Thus, we can narrow the timeline somewhat, and suggest that the postcard was almost certainly produced circa 1916 or 1917.

The Old Jewish Cemetery.

The old Jewish cemetery was the first Jewish cemetery established in Vilna. According to Vilna Jewish tradition, it was founded in 1487. Modern scholars, based on extant documentary evidence, date the founding of the cemetery to 1593, but admit that an earlier date cannot be ruled out. The cemetery, still standing today (but denuded of its tombstones), lies just north of the center of the city of Vilna, across the Neris River, in the section of Vilna called Shnipishkes (Yiddish: Shnipishok). It is across the river from, and just opposite, one of Vilna’s most significant landmarks, Castle Hill with its Gediminas Tower. The cemetery was in use from the year it was founded until 1831, when it was officially closed by the municipal authorities. Although burials no longer were possible in the old Jewish cemetery, it became a pilgrimage site, and thousands of Jews visited annually the graves of the righteous heroes and rabbis buried there, especially the graves of the Ger Zedek (Avraham ben Avraham, also known as Graf Potocki, d. 1749), the Gaon of Vilna (R. Eliyahu ben R. Shlomo, d. 1797), and the Hayye Adam (R. Avraham Danzig, d. 1820). Such visits still took place even after World War II.

The cemetery, more or less rectangular in shape, was spread over a narrow portion of a sloped hill, the bottom of the hill almost bordering on the Neris River. The postcard captures the oldest mausoleum and rabbinic grave in the old Jewish cemetery, exactly at the spot where the bottom of the hill almost borders on the Neris River. It was an especially scenic, and historically significant, site in the old Jewish cemetery, and it is no accident that the photographer chose this site for the postcard.

The Tombstone and its Hebrew Inscription.

The tombstone is that of R. Menahem Manes Chajes (1560-1636). He was among the earliest Chief Rabbis of Vilna. Indeed, his grave was the oldest extant dated grave in the Jewish cemetery, when Jewish historians first began to record its epitaphs in the nineteenth century. R. Menahem Manes’ father, R. Yitzchok Chajes (d. 1615), was a prolific author who served as Chief Rabbi of Prague. Like his father, R. Menahem Manes published several rabbinic works in his lifetime, and some of R. Menahem Manes’ unpublished writings are still extant in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. His epitaph reads:[2]

The Mausoleum and its Hebrew Inscription.

In the old Jewish cemetery, many of the more famous rabbis were buried in mausoleums. All rabbis buried in mausoleums were buried underground. The mausoleum itself served as an honorific place of prayer that a visitor could enter and then pray at the grave of the rabbi of his choice. All tombstones were placed outside the mausoleum, and were affixed to its outside wall, directly opposite the body of the deceased rabbi named on the tombstone (but buried inside the mausoleum). Often, the names of famous rabbis were painted on the outside wall of the mausoleum (much like street signs) identifying who was buried in it. The mausoleums sometimes contained the graves of several famous rabbis. R. Menahem Manes Chajes was buried in the mausoleum that can be seen behind his tombstone. A famous rabbi buried in the same mausoleum was R. Moshe Rivkes (d. 1672), author of באר הגולה on the Shulhan Arukh.[3] The inscription on its wall, and above the tombstone of R. Menahem Manes, reads:

פה מצבת הגאון הגדול ר‘ מאנש חיות

Here is the tombstone of the great Gaon, R. Manes Chajes

The Cemetery Attendant.

What has remained a mystery for more than one hundred years is the identity of the cemetery attendant. We shall attempt to identify him, and to restore him to his proper place in Jewish history.

The reader will wonder how I know that the person in the photograph was a cemetery attendant. Perhaps he was a tourist who just happened to be there on the day the Hochland Brothers Publishing Company arranged for a photograph to be taken for its postcard collection?

Initially, it was simply a hunch, largely due to ephemera, that is, other photos of visitors to the old Jewish cemetery in the interwar period. I have a collection of such photos, and either they feature the tourist (who handed his camera to the tour guide or to the cemetery attendant, and asked that his picture be taken in front of the Vilna Gaon’s tombstone or at the Ger Zedek’s mausoleum), or they feature a cemetery attendant who stands in those places, while the tourist, who knows how to use the camera, takes the photo. The tourists can always be recognized by their garb, which matches nothing worn by anyone else in Vilna. The cemetery attendants, functionaries of a division of the Jewish Kehilla (called Zedakah Gedolah at the time), all wear the same dress, a “Chofetz Chaim” type cap and a long coat, both inevitably dark grey or black. While I am not aware of another old Jewish cemetery photograph featuring the specific cemetery attendant seen in our postcard, his dress is precisely that of all the other cemetery attendants whose photos have been preserved.

But there is no need for guesswork here. Sholom Zelmanovich, a talented artist and Yiddish playwright, published his דער גר–צדק: ווילנער גראף פאטאצקי in 1934.[4]

This three-act play commemorates the life and death of the legendary Ger Zedek of Vilna in a new and mystical mode.[5] The volume includes sixteen original drawings by Zelmanovich. Several of the drawings preserve details of Vilna’s old Jewish cemetery with seemingly incredible accuracy. Thus, for example, Zelmanovich depicts the northern entrance gate to the old Jewish cemetery, as well as the nearby Jewish caretaker’s house on the cemetery grounds, even though few photographs are extant that even begin to capture the details of those sites. His depiction of the Ger Zedek’s grave (and the human-like tree that hovered over it) is perfectly located in the south-eastern corner of the old Jewish cemetery, and is surrounded by the wooden fence that existed in that corner prior to 1926. Only someone who spent quality time in Vilna’s old Jewish cemetery could have known exactly where to place the entrance gate, the caretaker’s house, and the Ger Zedek’s grave.

One other matter needs to be noticed. Zelmanovich dedicated the volume in memory of his deceased parents, Meir Yisrael son of Mordechai and Sheyne daughter of Broyne.[6]

In the summer of 1935, the municipal authorities of Vilna, then under Polish rule, announced their plan to demolish Vilna’s old Jewish cemetery and replace it with a soccer stadium. Vilna – and worldwide – Jewry did not stand idly by. Instead, they engaged in an extensive, and ultimately successful, battle against the municipal authorities. As part of its efforts to win over the municipal authorities, the Vilna Jewish community charged a young Jewish scholar, Israel Klausner,[7] with writing a history of the old Jewish cemetery. It would offer clear documentation and prove beyond doubt that various Polish kings and municipal authorities throughout the centuries had authorized the Jewish community to construct the cemetery and maintain it. The cemetery was legally the property of Vilna’s Jewish community. Klausner’s monograph, entitled קורות בית-העלמין הישן בוילנה (Vilna, 1935), includes a discussion of the Ger Zedek’s grave. In a footnote,[8] Klausner mentions in passing Sholom Zelmanovich’s “recently published drama on the Ger Zedek,” and adds that Zelmanovich was the son of the caretaker of the old Jewish cemetery (Hebrew: בן בעל–הקברות ), Meir Yisrael Zelmanovich! The plot thickens.

The full force of the Hebrew term בעל–הקברות is not really captured by the English term “caretaker.” There were a variety of cemetery attendants who worked in the old Jewish cemetery in various capacities (such as guiding visitors and leading them to the graves they wished to visit, reciting prayers at the graves, ground-keeping, repairing broken tombstones and re-inking their inscriptions, and guard duty). But one cemetery attendant was in charge of all the other attendants, and as we shall see, he and his family lived in the house on the cemetery grounds. He was called: בעל–הקברות, perhaps best rendered as: “Cemetery Keeper” or “Managing Director” of the old Jewish cemetery. We have established that Meir Zelmanovich served in that capacity. But who was he when did he live?

Meir Zelmanovich.

Sadly, almost nothing is known about the life of Meir Zelmanovich. He published no books and wrote no essays. As best I can tell, only one newspaper report mentions his name during his lifetime.[9] The report itself is significant. It records a complaint made by Meir Zelmanovich in 1919 that the Polish legionnaires had desecrated the old Jewish cemetery. But it would be Zelmanovich’s tragic death in 1920 that would perpetuate his memory. Here, we need to provide some historical context. Israel Cohen begins his discussion of the impact of World War I on Vilna, as follows:[10]

Within the small space of eight years, from 1914 to 1922, the Jews of Vilna tasted of the blessings of nine different governments, and suffered from a combination of other evils even more noxious. They became a prey to economic depression, military requisitions, unemployment, famine and disease; thousands of them were subjected to forced labor, imprisonment, plunder and brutal attacks; and physical and material deterioration inevitably engendered a certain degree of social demoralization. All the variegated differences of principle, of religious outlook and sociological doctrine, were now forgotten in the inferno created by the common foe. The long protracted fight for civil and political rights had to yield to the more primitive and desperate struggle for mere existence.

Almost certainly, the greatest concentration of Jewish suffering in this period came in April of 1919, when the Polish legionnaires unleashed a pogrom against Vilna’s Jews. Israel Cohen describes the horrors that followed:[11]

The [Polish] legionnaires[12] defiled and desecrated the [old Jewish] cemetery, smashed the tombstones, and opened the graves (including some of Vilna’s earliest rabbis) in the belief that they would find in them arms and money. Disappointed in their search, the Poles transferred their attentions from the dead to the living and ran amuck in the Jewish quarter. For three days they seized Jews in the streets, dragged them out of their homes, bludgeoned them savagely, and looted their houses and shops. About 80 Jews were shot, mostly in the suburb of Lipuvka, where some were ordered to dig their own graves; others were buried alive, and others were drowned, with their hands tied, in the Vilia [now: Neris] River… All sorts of outrages were committed in those days by the Poles in celebration of their victory. They tied a Jew to a horse and dragged him through the streets for three miles. They took a sadistic delight in cutting off the beards and earlocks of pious Jews. They even arrested, assaulted and humiliated Rabbi Rubinstein and Dr. Shabad. Altogether, thousands of Jews in Vilna, as well as in Lida and Bialystock were imprisoned in various concentration camps where they were ill fed and beaten, and where they suffered from hunger and typhoid. Moreover the total loss due to destruction and pillaging of Jewish people in the pogrom, in Vilna alone, was estimated at about 20 million roubles (about $10,000,000).

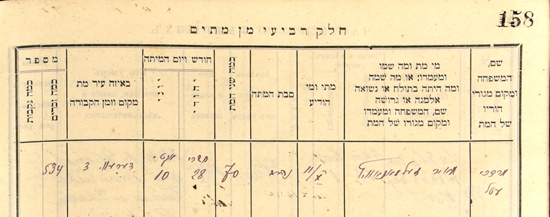

Polish rule of Vilna came to an end when the Russians recaptured Vilna on July 14, 1920. Russian rule lasted for six weeks, after which the Russians retreated and left Vilna in the control of the Lithuanians. Lithuanian rule lasted until October 8, 1920, when the Poles once again recaptured Vilna. One can only imagine the fear that gripped the Jewish community in Vilna, when they heard the sounds of the approaching Polish legionnaires. In fact, hundreds (some claim: thousands) of Vilna’s Jews fled on October 8 to Kovno, then part of Independent Lithuania.[13] Indeed, there was what to fear, for the Polish legionnaires were free again to wreak havoc with Jewish lives. And although the severity of the pogrom of 1919 did not repeat itself, the indiscriminate murder, rape, and looting of Jews that took place in Vilna between October 8-10, 1920 was, at least in the eyes of the victims, yet another pogrom.[14] Briefly, eye-witness Yiddish accounts[15] record that at least 6 Jewish men and women were murdered, numerous women were raped, and some 80 Jews were mugged and robbed. No one was brought to justice for committing these crimes! On October 10, 1920 Meir Zelmanovich, Cemetery Keeper of the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna was murdered by the Polish legionnaires. He was 70 years old when he died. The official Jewish record of his death lists his home address as “Derewnicka 3.” This is the address of the house on the grounds of the old Jewish cemetery. It is no wonder that Sholom Zelmanovitch could depict so vividly the northern entrance gate to the cemetery, its nearby caretaker’s house, and the human-like tree hovering over the Ger Zedek’s grave. His childhood playground was the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna.

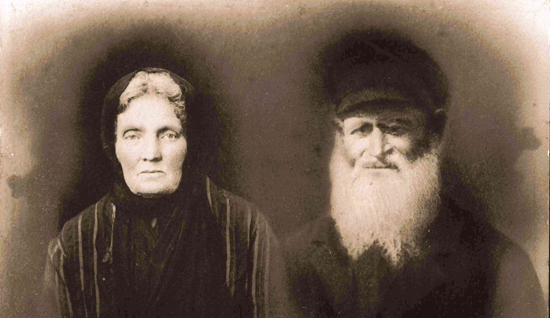

On the picture postcard from 1916-1917, one sees an elderly Jew. One possibility is that it depicts none other than Meir Zelmanovitch, the Cemetery Keeper of the old Jewish cemetery until his death in 1920 at age 70. I suspected that this was the case, but could not prove it until recently — when a small miracle occurred.

Miracles Sometimes Do Occur.

In March of this year, out of the clear blue sky, I was contacted by Laurie Cowan, who introduced herself as a great-granddaughter of Meir Zelmanovich! She basically was interested in any information I could provide about her great-grandfather that she didn’t already know. I was delighted to make her acquaintance, but wondered what led her to me. It turns out that both of us were seeking information about the same person – Meir Zelmanovich – from the Lithuanian State Historical Archives in Vilnius. An alert researcher at the Archives noticed this, and made the “shidduch” between us. I shared with Laurie whatever I knew about her great-grandfather. In turn, I asked her to send me copies of whatever documents she had relating to her great-grandfather. She sent me a scan of the following photograph of her great-grandmother and great-grandfather, Sheyne[16] and Meir Zelmanovich:

Never has it been so easy to identify an unidentified picture on a one-hundred year old picture postcard! One suspects that the picture postcard company representative, and a photographer, met with the Cemetery Keeper Meir Zelmanovich at the old Jewish cemetery in Shnipishok. He led them to the mausoleum of R. Menahem Manes Chajes, and was asked to pose at the tombstone just outside it. He graciously accepted the invitation. This may well have been the last photo taken of Zelmanovich, and it preserves, together with the photo provided by Laurie Cowan, the likeness of a martyr who fell during the October 1920 mini-pogrom in Vilna.[17]

At least six Jews were murdered between October 8-10 in 1920 in Vilna. They died for one reason only, namely, because they were Jews. Such Jews are regarded as martyrs and their names, at the very least, deserve to be recorded and remembered. Until now, none of the names of the Vilna martyrs of 1920 have been published in any public Jewish record, whether in a contemporary Jewish newspaper, or a Jewish historical essay or book, or an online posting. Having examined the extant records in the Lithuanian State Historical Archives, I have been able to retrieve the 6 names of the Jewish victims who were murdered in Vilna in October of 1920. In each case, the Jewish Kehillah records of Vilna in 1920 state clearly in Hebrew that the cause of death was either נהרג or נהרגה (i.e., murdered). The names are:

1. Shmuel ben Mendel Katz, age 56, died October 9.

2. Etel Natin, age 36, died October 9.

3. Basya Natin, age 32, died October 9.

4. Rokhl Blume Shuster, age 45, died October 9.

5. Meir Zelmanovich, age 70, died October 10.

6. Shlomo Abramovich, age 17, died October 12.[18]

May the memory of these martyrs be forever for a blessing! [19]

NOTES:

* עם הספר, the People of the Book the world over, mourn the death of R. Shmuel Ashkenazi in Jerusalem, at the age of 98. He was שר הספר, the consummate master of the Hebrew book. Bibliographer, bibliophile, and book collector, his encyclopedic knowledge of all of Hebrew and Yiddish literature remains unparalleled in our time. His most recent contributions appeared in three massive volumes, replete with some 1,794 pages of immaculate scholarship. He never wasted a word; he wrote with precision and parsimony. Among his many accomplishments, he edited the Kasher Passover Haggadah, one of the most significant scholarly editions of the Passover Haggadah ever published. He was largely responsible for the single most accurate bibliography of Hebrew books ever produced, מפעל הביבליוגרפיה העברית: The Bibliography of the Hebrew Book 1473-1960. Aside from his scholarly distinction, R. Shmuel Ashkenazi wrote in an elegant Hebrew with its own special charm. Not only did he advance discussion, but he did so in an aesthetically pleasing manner. For those of us who knew him personally, he evinced the same charm in his personal relationships that he did in his writings. He set a standard of excellence that we can only strive to emulate, but never really replicate. יהא זכרו ברוך!

This essay is dedicated to his memory, a token of appreciation for all he has taught me.

[1] Dovid Katz, “World War I Postcard of the Grave of Rabbi Menachem Manes Chayes (1560-1636) in the Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery,” Defending History (11 March 2020), available here) A copy of our postcard can also be seen online at ‘YIVO 1000 Towns’, record ID 10743 (http://yivo1000towns.cjh.org).

[2] For a fuller discussion of R. Menahem Manes Chajes and his epitaph, see S. Leiman, “A Picture and its One Thousand Words: The Old Jewish Cemetery of Vilna Revisited,” The Seforim Blog, January 14, 2016, especially notes 7-11, online here.

[3] Aside from his pivotal commentary on R. Joseph Karo’s Shulhan Arukh, R. Moshe Rivkes was a great-great grandfather of the Vilna Gaon.

[4] Precious little is known about Sholom Zelmanovich (1898-1941). See the brief biographical entry in לעקסיקאן פון דער נייער יידישער ליטעראטור (Martin Press: New York, 1960), vol. 3, column 670, which mistakenly lists him as being born in a town near Kovno, circa 1903. He was born in Vilna in 1898 (JewishGen) and died during one of the first Nazi aktions in the Kovno Ghetto.

[5] In general, see Joseph H. Prouser, Noble Soul: The Life and Legend of the Vilna Ger Tzedek Count Walenty Potocki (Gorgias Press: Piscataway, 2005). Prouser’s excellent monograph is a study of the many literary reworkings of the legends surrounding the Vilna Ger Zedek, with primary focus on 20th century Jewish literary contributions. Strangely, he offers no discussion of Zelmanovich’s contribution.

[6] On the feminine Yiddish name “Broyne,” see Alexander Beider, Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names (Avotaynu: Bergenfield, 2001), pp. 484-486.

[7] Klausner (1905-1981) settled in Palestine in 1936 and continued to be a prolific author of studies and books on the history of Vilna’s Jewish community. Aside from several important monographs, like his history of the old Jewish cemetery, he wrote a two-volume history of Jewish Vilna entitled 1939-1881 וילנה ירושלים דליטא: דורות האחרונים (Ghetto Fighters’ House: Tel-Aviv, 1983), to which a third volume treating 1495-1881 was added posthumously, based largely on studies previously published by Klausner.

[8] קורות בית–העלמין הישן בוילנה, p. 45, note 1.

[9] See Vytautas Jogela, “The Old Jewish Cemetery in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Lituanus, vol. 61, no. 4 (2015), pp. 81-82.

[10] Israel Cohen, Vilna (Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia, 1943), pp. 358-359.

[11] Ibid., pp. 378-379.

[12] Cohen regularly spells the word: “legionaries.” For the sake of consistency, I have spelled the word “legionnaires” throughout this essay.

[13] See, e.g., Boaz Wolfson, “מיטל–ליטע” in פנקס פאר דער געשיכטע פון ווילנע אין די יארן פון מלחמה און אקופאציע (B. Zionson: Vilna, 1922), column 387.

[14] There are probably as many definitions of “pogrom” as there are scholars and politicians. Since it is unclear whether the crimes committed on October 8-10, 1920 were planned and implemented by either a government or a political action committee, and since the duration of the attacks was short and rather swiftly brought under control, historians are reluctant to refer to the events that occurred on October 8-10, 1920 as a pogrom. On the other hand, to label those events a mere “disturbance” does not begin to capture the malevolent intent of the perpetrators directed specifically against Jews, and does not address the intensity of Jewish suffering at the time. For some of the different views regarding the definition of “pogrom,” and how the term has been manipulated by political interests, see Szymon Rudnicki’s forthcoming essay “The Vilna Pogrom of 19-21 April 1919,” to appear in Polin 33 (2020). Professor Rudnicki kindly allowed me to see a pre-publication copy of his lucid and informative essay.

[15] Wolfson, loc. cit. Cf. Jacob Wygodski, אין שטורם (B. Kletzkin: Vilna, 1926), pp. 217-221.

[16] Sheyne Zelmanovich died in Vilna on October 26, 1921, at age 68 (JewishGen). She lived in her home on the old Jewish cemetery grounds until her death. In a personal communication, Laurie Cowan informed me that the Zelmanoviches had 10 children who survived to adulthood. The 6th child, Beirach (popularly called: Berik; and later, Ben), was her grandfather, an older brother of Sholom mentioned above.

[17] The only other extant likeness of Meir Zelmanovich (known to me, and recovered on July 15, 2020) is an undated passport photo (circa 1916) preserved in the Lithuanian State Historical Archives. During the German occupation, all residents of Vilna were required to have – and to carry at all times – a German passport (we would call it: an Identity Card). Meir Zelmanovich’s German passport photo confirms the identity and authenticity of the photos of Zelmanovich published in this essay. All three photos are of one, and the same, person.

[18] One suspects that Abramovich may have been shot or beaten on October 9 and 10, like the others, but did not die from his wounds until the 12th.

[19] This essay could not have been written without the help of Regina Kopilevich, researcher (and tour guide) extraordinaire, who located whatever documents I sought at the Lithuanian State Historical Archives (Lietuvos Valstybes Istorijos Archyvas) in Vilnius. I am indebted to the librarians at the Archives for allowing her and me to examine these and other documents during my visits to Vilnius. Next to Google, JewishGen is a modern Jewish historian’s best friend, and we are grateful to all who contribute to making JewishGen the great historical resource that it is. Matt Jelen’s careful reading of an earlier draft has significantly improved the final version. I alone am responsible for whatever errors appear in this essay.

28 thoughts on “In Praise of Ephemera: A Picture Postcard from Vilna Reveals its Secrets More than One Hundred Years after its Original Publication”

Thank you Professor Leiman!

If we owe this excellent and timely bit of scholarship to your pursuit of respite from your inveterate condition, you will have to forgive us if we don’t bid you a speedy recovery from it. However, I would posit that by publishing this essay, you have perpetuated the ephemeral, and just like that you have obviated the need for a cure altogether!

Thanks for yet another fascinating article. When will your website, leimanlibrary.com, be up again as the articles contained on it are currently inaccessible?

It is currently under repairs for updating 🙂

Another fantastic article by Dr. Leiman. Thank you for sharing this and making the names of those kedoshim known.

What can one add to such an erudite study of ephemera? So, just a note of appreciation for a scholar with a keen eye for significant details on tombstones.[1]

It pertains not to Meir Zelmanovich, but rather to the tombstone of R. Menahem Manes Chajes. Those familiar with the Chajes family, know that its origins were in Provence as the title page of the 1589 sermon of Menahem Manes’s father, Yitzhak, rabbi of Prague, Prossnitz and elsewhere attests [2]: ״מגזע חסידי פרובינצה״. Recently, the tombstone of Menahem Manes’s brother Avraham was discovered in Gorodok, Ukraine and the bottom line repeats this claim.[3] Although it is not such a grave matter, it is nevertheless striking that this historical detail, which seems to have had some importance for the family, is not mentioned on Menahem Manes’s tombstone.[4]

[1] Sid Z. Leiman, “Mrs. Jonathan Eibeschuetz’s Epitaph – A Grave Matter Indeed,” in Leo Landman, ed., Scholars and Scholarship (NY, 1990), pp. 133-143.

[2] https://hebrewbooks.org/11696

[3] https://www.zadikim.com/גורודוק__גילוי_מדהים___קברו_של_רבי_אברהם_חיות

[4] The title page of Binyan ha-Bayit (1775) by Yehiel Hillel Altschuler, a descendant of Yitzhak Chajes, also mentions the Provencal connection. https://www.hebrewbooks.org/21420

Thanks. It woke me up instead of putting me to sleep. I may be coming down with Ephemeritis.

On another topic, I wonder if perhaps Rabbi Chajes is a Great Grandfather of Abram Chayes, a law professor at Harvard and a colleague of Louis Henkin?

The Maharatz Chajes was a descendant, if that helps.

ישר כח on a very interesting article which adds to Prof. Leiman’s contribution to the history of Vilna in particular regarding the old cemetery and the order of the transfered graves in the current Ohel of the Vilna Gaon זצ״ל.

Prof. Leiman’s personal site will be back up and running within the next few weeks, and until then, you can access the materials on his website here (https://tinyurl.com/y3dz9odx), or by going to LeimanLibrary.com and following instructions to proceed from there.

Thanks.

Thanks for once again sharing the fruits of your inspiring scholarship. Your ability to magically transport us in time, and bring events and personalities to life who otherwise would remain obscure, is a rare gift.

May the holy neshama of R. Shmuel Ashkenazi have an Aliyah.

Wow! I read the article spellbound. Thank you.

K’vod HaRav,

Wonderfully written — my kind of history-mystery. As one involved in cemeteries and the inscriptions on matzevot, this was also a plus.

Related to the photography issue, similarly I have rued the lack of photographs of how our ancestors might have looked in their youth. How fortunate you were able to make this comparison and identification!

kol ha’kavod on your work.

What a great read. Thanks so much!

Was it customary to refer to the father as “son of [Mordechai]” while referring to the mother as “daughter of [Broyne]” I think it’s common today for ashkenazim to always link to the male parent “daughter of Gershon” for example?

Wonderful article, Shnayer! YK!

Many thanks, Shnayer, for all the relentless, exhaustive sleuthing you have always invested in your lifelong, peerless scholarly pursuit of Truth — wherever it may take you.

וכן ירבו עד מאה ועשרים

Thanks so much for this extraordinary article. As someone who collects Jewish ephemera — this was a wonderful read. Your scholarship is simply outstanding! It will serves as an inspiration to others doing this very important and holy work.

kol hakavod!

My gang on Google+ would get a lot from this post. Is it okay if I link it to them?

Win a lamborghini huracan!!! register you !!

win money 2019

win money to pay off student loan

win ferrari

play and win btc

win money competitions

win money dream

win money games free

Great material. Thnks a lot.

Best Essay writing

alternative fuels https://an-essay.com/workshop-four-41