An Unpublished 1966 Memorandum from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan Answers Questions on Jewish Theology

An Unpublished 1966 Memorandum

from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan Answers Questions on Jewish Theology

Marc B. Shapiro and Menachem Butler

Professor Marc B. Shapiro holds the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Scranton, and is the author of many books on Jewish history and theology. He is a frequent contributor at the Seforim blog.

Mr. Menachem Butler is Program Fellow for Jewish Legal Studies at The Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School. He is an Editor at Tablet Magazine and a Co-Editor at the Seforim Blog.

Over the last ten years Professor Alan Brill has written a series of blogposts, as well as a recent scholarly article on the perennially interesting, yet historically mysterious, rabbinic theologian, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan (1934-1983).[1] It was from these posts that many have learned about what Kaplan was doing before he burst onto the wider Jewish literary scene in the early 1970s through his writings and public lectures. He passed away in 1983 at the age of 48.[2]

Rabbi Aryeh (Leonard M.) Kaplan was born in the Bronx in 1934, and studied at Mesivta Torah Vodaath in New York, and at the Mirrer Yeshiva in New York and in Jerusalem. In 1953, 20-year-old Aryeh Kaplan joined the group of students assembled by Rabbi Simcha Wasserman under the guidance of Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky to establish a yeshiva in Los Angeles,[3] and three years later in 1956 received his rabbinic ordination (Yoreh Yoreh, Yadin Yadin) from Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel of the Mirrer Yeshiva of Jerusalem, and from the Chief Rabbinate of the State of Israel. After receiving his ordination, Aryeh Kaplan began his undergraduate studies and, in 1961, earned a B.A. in physics from the University of Louisville, and two years later, an M.S. degree in Physics from the University of Maryland, in 1963. While studying towards his undergraduate degree, Aryeh Kaplan taught elementary school at the pluralistic Eliahu Academy in Louisville, and corresponded with Rabbi Moshe Feinstein about some of the challenges that he encountered.[4] He then worked for four years as a Nuclear Physicist at the National Bureau of Statistics in Washington DC.

In February 1965, Rabbi Kaplan and his wife and their two small children moved to Mason City, Iowa, where he was invited to serve as a pulpit rabbi at Adas Israel Synagogue, a non-Orthodox congregation with forty member families. It would be his first pulpit. He remained at that pulpit until July 1966. During his time in Mason City, Rabbi Kaplan and his wife were very active in all aspects of their synagogue activities. Rabbi Kaplan led services and delivered a sermon each week at the Friday Night Service at Adas Israel Synagogue, hosted a Talmud Torah and taught about Jewish tradition to the youth in the community. He was a member of the National Conference on Christians and Jews, and regularly hosted visiting religious groups to the synagogue and participated in interfaith meetings and on panels alongside religious leaders of other faiths. In all of his delivered remarks, Rabbi Kaplan would type out each sermon prior to its delivery and maintain copies of these addresses within his personal archives; to date, these sermons have not yet been published.

It was during Rabbi Kaplan’s time in Mason City that he authored a fascinating eleven-page-typescript memorandum, dated February 22, 1966, that, thanks to the research discovery of Menachem Butler, we are privileged to share with the readers of The Seforim Blog in the Appendix to this essay.[5]

Kaplan was responding to questions sent out by the B’nai B’rith Adult Jewish Education bureau in Washington DC on matters of basic Jewish theology.[6] We see from the letter that like many other rabbis who were serving in frontier communities, Kaplan maintained a camaraderie with those among the non-Jewish clergy. He was even a member of the “Ministerial Association,” and together with his wife was “founder and chairman of the local chapter of Ministerial Wives.” As one who often hosted non-Jewish groups at the synagogue, Kaplan was well equipped to place Jewish concepts and practices within a context that would make sense for Christians, and this is clearly seen in how he formulates his answers in the letter.

Although Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s memorandum is self-explanatory, there are a few points of theological interest that are worth calling attention to:

1. Right at the beginning, Kaplan notes that Jews have no official dogmas, and that in many cases Jewish opinions vary widely.

2. Kaplan states unequivocally that Maimonides does not believe in a literal resurrection. In support of this statement he cites Guide 2:27. If all we had were the Commentary on the Mishnah and the Guide, it would make sense to assume that when Maimonides refers to the Resurrection of the Dead that he intends immortality, not literal resurrection. Even the Mishneh Torah can be read this way, and Rabad, in his note on Hilkhot Teshuvah 8:2, criticizes Maimonides in this regard: “The words of this man appear to me to be similar to one who says that there is no resurrection for bodies, but only for souls.” Furthermore, in Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:6, in speaking of the heretics who have no share in the World to Come, Maimonides writes: והכופרים בתחית המתים וביאת הגואל, “Those who deny the Resurrection and the coming of the [messianic] redeemer.” Throughout his works Maimonides is clear that the ultimate reward is the spiritual World to Come. So how could he not mention among the heretics those who deny the World to Come, and only mention those who deny the Resurrection? It appeared obvious to many that when Maimonides wrote “resurrection of the dead” what he really meant is the spiritual “World to Come.”

As noted, if the works mentioned in the previous paragraph were all we had, then one would have good reason to conclude that for Maimonides resurrection of the dead means nothing other than the World to Come. Yet it is precisely because people came to this interpretation that Maimonides wrote his famous Letter on Resurrection in which he states emphatically that he indeed believes in a literal resurrection of the dead, after which the dead will die again and enjoy the spiritual World to Come. It is true that some have not been convinced by the Letter on Resurrection and see it as an work letter that does not give us Maimonides’ true view, but such an approach means that one is accepting a significant level of esotericism in interpreting Maimonides, as we are not now concerned with a passage here or there but with an entire letter that one must assume was only written for the masses. Since Kaplan ignores what Maimonides says in his Letter on Resurrection, I think we must conclude that, at least when he wrote this letter, he did not regard it as reflecting Maimonides’ authentic view.[7] In Kaplan’s later works, there is no hint of such an approach to Maimonides.[8]

3. In discussing Jesus, Kaplan writes: “In this light, we can even regard the miracles ascribed to Jesus to be true, without undermining our own faith, since his message was not to the Jews at all.”[9]

APPENDIX:

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: Response to “Questions Christians Ask Jews” (1966)

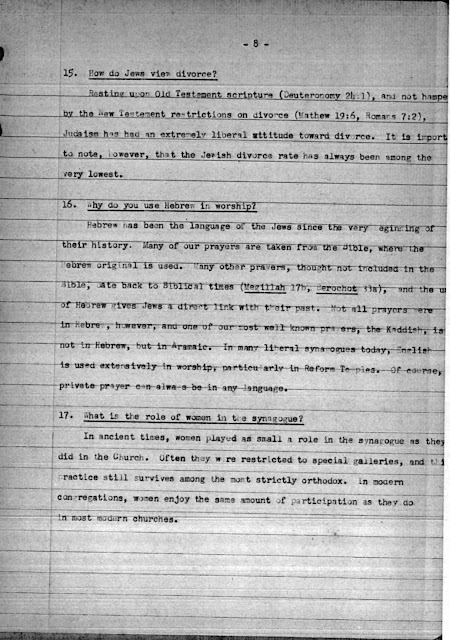

[INSERT IMAGES 1-13]

Notes:

[1] See Alan Brill, “Aryeh Kaplan’s Quest for the Lost Jewish Traditions of Science, Psychology and Prophecy,” in Brian Ogren, ed., Kabbalah in America: Ancient Lore in the New World (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 211-232, available here. See also Tzvi Langermann, “‘Sefer Yesira,’ the Story of a Text in Search of Commentary,” Tablet Magazine (18 October 2017), available here.

[2] A complete biographical portrait of Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan remains a scholarly desideratum.

For appreciations of his writings, see “Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: A Tribute,” in The Aryeh Kaplan Reader: The Gift He Left Behind (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1983), 13-17; Pinchas Stolper, “Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan z”l: An Appreciation,” Ten Da’at, vol. 1, no. 2 (Spring 1987): 8-9; Baruch Rabinowitz, “Annotated Bibliography of the Writings of Aryeh Kaplan, Part 1,” Ten Da’at, vol. 1, no. 2 (Spring 1987): 9-10; Baruch Rabinowitz, “Annotated Bibliography of the Writings of Aryeh Kaplan, Part 2,” Ten Da’at, vol. 2, no. 1 (Fall 1987): 21-22; and Pinchas Stolper, “Preface,” in Aryeh Kaplan, Immortality, Resurrection, and the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1993), ix-xi, among other writings.

[3] See Nosson Scherman, “Rabbi Mendel Weinbach zt”l and The Malbim,” in A Memorial Tribute to Rabbi Mendel Weinbach, zt”l (Jerusalem: Ohr Sameyach, 2014), 13-14, available here; as well as Nissan Wolpin, “The Yeshiva Comes to Melrose,” The Jewish Horizon (March 1954): 16-17.

[4] See responsum by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein as published in Shu”t Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim, vol. 1 (New York: Noble Book Press, 1959), 159 (no. 98), dated 13 July 1955.

Discovery of additional correspondences between Rabbi Moshe Feinstein and Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan during those years would be of great scholarly interest and of immense historical value.

[5] Menachem Butler is also preparing for publication the typescript text of a sermon (“If This Springs From G*D…”) that Rabbi Kaplan delivered the previous month in January 1966, and where he reveals details about a conversation that he had with Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Project and father of the Atom Bomb.

[6] Menachem Butler writes two interesting details that, though beyond the narrow scope of this essay, are nonetheless of historical worthiness to consider when reading this memorandum:

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s memorandum of February 1966 was written several months *prior* to the famous symposium of “The State of Jewish Belief:” hosted by Commentary in August 1966, and republished shortly-thereafter under the different title The Condition of Jewish Belief: A Symposium Compiled by the Editors of Commentary Magazine (New York: Macmillan, 1966), and reprinted more than two decades later in The Condition of Jewish Belief (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc., 1988). One wonders how Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan might have responded to the five questions sent by Commentary to 38 rabbis and scholars from around North America.

Returning to questions submitted by B’nai B’rith, it should be noted that the 21 questions were composed by Rabbi Morris Adler on behalf of the B’nai B’rith Adult Jewish Education bureau, a commission that he chaired from 1963-1966, and that he was murdered several weeks after the memorandum was submitted by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. It is for this reason that I believe that these responses had not been published.

The circumstances of Rabbi Adler’s assassination are that a gunman shot him multiple times during Shabbat morning services in front of hundreds of his congregants at his synagogue in Michigan. Rabbi Adler passed away from his wounds sustained in the attack nearly a month later. For a brief bibliographical portrait, see Pamela S. Nadell, Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), 31-32; and for a full book-length account of the episode, see T.V. LoCicero, Murder in the Synagogue (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1970), as well as his followup volume in T.V. LoCicero, Squelched: The Suppression of Murder in the Synagogue (New York: TLC Media, 2012), available to be ordered here.

[7] For brief discussion, see Isaiah Sonne, “A Scrutiny of the Charges of Forgery against Maimonides’ ‘Letter on Resurrection’,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, vol. 21 (1952): 101-117; see also Jacob I. Dienstag, “Maimonides’ ‘Treatise on Resurrection’ – A Bibliography of Editions, Translations, and Studies, Revised Edition,” in Jacob I. Dienstag, ed., Eschatology in Maimonidean Thought: Messianism, Resurrection, and the World to Come (New York: Ktav, 1983), 226-241, available here.

[8] See Aryeh Kaplan, Maimonides’ Principles: Fundamentals of Jewish Faith (New York: National Conference of Synagogue Youth, 1984), Aryeh Kaplan, Immortality, Resurrection, and the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1993), among other publications.

[9] The notion that in the past non-Jews have performed miracles much like the Jewish prophets needs further analysis, which Marc B. Shapiro will attempt in his forthcoming book on Rav Kook. As well, in Toledot Yeshu Jesus is described as performing miracles, but this is explained by Jesus having made use of God’s holy name.

45 thoughts on “An Unpublished 1966 Memorandum from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan Answers Questions on Jewish Theology”

I’m not a fan of publishing this type of material. Key issue being that R’ Kaplan rose to fame at a later point, when he wasn’t publishing this type of ideology, and it’s very possible that his views on such matters changed. He published quite a lot, and would have had ample opportunity to express such views had he so chosen.

Publishing such material has the potential to tarnish his memory in circles which currently respect him, and it’s possible that he would specifically not want such material published.

On the flip side, it’s also the case that representing such views as being the views of “R’ Aryeh Kaplan” with the connotation of the well-known scholar is potentially misleading, if the well-known scholar which he later became no longer held those views.

Thank you for your anonymous thoughts.

In generalI think the logic here is quite faulty as even after death we can question whether Rabbi Kaplan would change his mind if he had lived to a ripe old age….

That notwithstanding, have you studied his books? There is very little, if anything, that he wrote here, which I haven’t already seen in a different work of his. I’m not sure as to which views here you think he did Not take the opportunity to express….

Your comparison of an apparent change of heart later in life to a *potential* change late in life does not make sense. Whether he actually had a change of heart and chose not to publish for that reason is a different question though.

“Apparent change”? We don’t know how he felt about it. Just because he didn’t publish it in his writings geared toward the Orthodox community doesn’t mean he had a change of heart regarding those subjects.

I’ve not studied his books exhaustively. As a kid I read some of his philosophical/theological (& Breslover!) stuff. I later read his Living Torah (which is much more impressive, IMHO). (I’m pretty sure one of his kids was in my class in school back in the day – he was, at least at the time, a Klausenberger chosid IIRC.)

I assume he didn’t say of these things in his published works, partially because we would probably have heard of it earlier (ala Slifkin), but mostly because the authors of this blog post wouldn’t be making a big deal about how they discovered these things in some obscure unpublished work if R’ Kaplan had published them.

Your note is valid, but I’d like to think that seforimblog readers are sufficiently sophisticated and nuanced to understand that authors and thinkers, particularly highly-intelligent ones with out-of-the-box characters and backgrounds, often don’t think in black-and-white absolutes, and we understand that Kaplan’s views may have changed over time, as well as that his presentations are context specific to their time, place and audience.

I also second the opinion of other commenters who noted that ideas presented by Kaplan in the context of interfaith dialogue in mid-America of the 1950s would have been presented differently to a frum audience in Brooklyn in the 1980s. (In general I find the tone and messaging of Kaplan’s article to be very “mid-20th century America”.)

I agree that this post may not have been right for, say, Mishpacha Magazine, but I think it’s totally okay for seforim blog; in fact that’s why a particular audience comes to seforim blog in the first place; we’re very happy to keep this a place that’s open to slightly more ‘edgy’, non-mainstream material.

Joseph, I agree with you completely that this site is so” geshmak” because one can find content here not available in any other place.However there are some contributers that although fantastic writers , intellects and well meaning are totally oblivious in understanding context and historical perspective .I feel it’s always worthwhile to point this out even where it seems so obvious to most.

Incredible!! A huge yasher koach for publishing this.

Are you aware of other “positive״ comments made by R Aryeh Kaplan concerning Reform Judaism?

“Other”? I don’t know how this can be spun as “positive” comments about Reform. This isn’t even positive about Orthodox Jews. It’s a dispassionate statement of the range of beliefs among Jews. He had the intellectual honesty, writing from Iowa to the Bnai Brith in the 1960s, not to pretend that the Reform didn’t exist. That’s not exactly “positive.”

“While studying towards his undergraduate degree, Aryeh Kaplan taught elementary school at the pluralistic Eliahu Academy in Louisville, and corresponded with Rabbi Moshe Feinstein about some of the challenges that he encountered.”

The referenced responsum in Igros Moshe is dated 1955, which is not during the time period that R Kaplan was studying towards his degree.

So it would seem that the sentence above is imprecise, unless you know of additional correspondence with Rav Moshe during the time R Kaplan was studying for his degree.

What was he doing in 1955? Do you know the background to this responsum?

My understanding (based on my research) is that the 1955 date *is* within the time period that Rabbi Kaplan was studying towards his degrees. Happy to discuss this with you further offline, as this is part of ongoing research into Rabbi Kaplan and his early years.

I don’t know the slightest thing about when RAK began studying for his degrees. But you yourself wrote in this very post that “… in 1956 received his rabbinic ordination … After receiving his ordination, Aryeh Kaplan began his undergraduate studies”

Having been R. Kaplan’s pupil in Louisville, I can state with certainty that he arrived there in August/September 1956 and, to the best of my knowledge, did not enroll at the University of Louisville until the next year. If memory serves, he received his B.S., married, and left Louisville in the summer of 1961.

Thank you Lenn! Any idea what he was doing in 1955 that motivated his letter to Rav Moshe?

Hi Lynn how can I get intouch with you? Aryeh Rosenfeld Rabbi Kaplans grandson.

On another note, the first point made, that “Right at the beginning, Kaplan notes that Jews have no official dogmas, and that in many cases Jewish opinions vary widely” is a distortion of what R’ Kaplan wrote, as to the first half. He did not say there is no official dogma.

What he said is that there are all sorts of Jews with all sorts of beliefs, from ultra-orthodox to Reform. That’s not at all the same thing as saying there’s no official dogma. And even saying that “Jewish opinions vary widely” is true to the extent that as a practical matter there are many Reform Jews out there and their opinions vary widely from Orthodox belief. That’s not to imply that those beliefs are acceptable from an Orthodox perspective.

Read the cover letter where he says Jews have no official dogmas

I hadn’t noticed that. My apologies.

That said, it does seem to me that his words were intended to mean that as a practical matter there was a broad spectrum of beliefs among people calling themselves Jewish, and no dogma which applied universally to all streams of Judaism. In that same sentence, he goes on to compare Jews to Christians in this regard, and Christians very much do have official dogma, though most of it is specific to the branch of Christianity and not accepted by those of other branches.

But again, I did miss the cover letter. Sorry again.

Fascinating, thank you. Alan Brill’s articles (linked above) are also very interesting, as is an appreciation of RAK by Ari Kahn, which is linked in the comments to one of the Brill pieces.

You note the question surrounding the Rambam, and the different views he expressed in different sources. Did he himself believe what he wrote in Source X, or was it said only for the sake of a particular audience? We will never know. But we can be confident that regardless of what he personally believed, he would not have said anything he felt was actually wrong. It thus doesn’t really matter what the Rambam himself thought, if he acknowledged that another position was also possible.

The same can be said about RAK. He was a man who occupied many worlds and spheres, and the vanished world from which he wrote was in a completely different dimension from our world today. It’s not important precisely what he believed, and its quite possible he himself never fully made up his mind. The main thing is like the Rambam, he would not have said anything he thought was wrong.

It seems apparent from the inclusion of non-Orthodox opinions in just about every item in this response that RAK’s goal in writing wasn’t to present his personal stance on the issues but to provide curious Christians a window into Judaism. As such, one can question how much his reference to Maimonides’ denial of a literal resurrection reflects his personal understanding of Maimonides’ true view. The “Maimonides Non-Literal View of Resurrection” approach is indeed advocated by some scholars and can be cited alongside the approach to kashrus which allows for limiting it to the home and the like.

“Cannon Law”, with two Ns? Is that the body of law relevant only during warfare?

And “homoletics.” The study of how to twist Judaism to make it say that same-sex relationships are to be celebrated?

As far as I know, the National Bureau of Statistics to which you ascribe R. Kaplan’s employment does not/did not exist. Perhaps you meant the National Bureau of Standards? – a storied federal research institution in Gaithersburg, MD which has notched a number of physics Nobels. Subsequent to the start of my wife’s (a senior computer scientist) own employment there it’s been renamed the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). But it’s still winning Nobel prizes.

Thank you for publishing this. In general important work remains to be done on the social and intellectual history of American Orthodoxy (particularly outside of NYC—both in other large cities as well as smaller cities and towns).

This includes as you suggest the role of the Orthodox professional (in this case clergy) in the broader community. Which as you write involved not only practical cooperation but also the question of ideological and philosophical values and practices. Your work attempts to apply Professor Jacob Katz’s foundational thinking about the history of Orthodoxy to America.

It’s always interesting to get a glimpse of process. He started page 1 writing “G-d”. But at the bottom of the page, he overtyped the dash with an “o”, and then continued in the rest of the document to write it out with an “o”.

I have this same process to this day undecided about how to write it when writing for goyim. 🙂

Readers might be interested in something R. Nisson Wolpin of the Jewish Observer said when he was a speaker at a long-running Friday night lecture series in Boro Park’s Bnei Yehuda (R. Israel Kirzner’s shul), which was organized I believe by Dr. Marvin Schick.

I recall that R. Wolpin said that R. Aryeh Kaplan told him that he had a weakness, in that he once swapped pulpits with a non-Jewish clergyman (or something similar), and that is why he did not want to return to the rabbinate. I found this inspiring in the spirit of “Making of a Gadol”, since R. Kaplan was aware of that “weakness”, yet proceeded with his writing and teaching; that weakness also ended up benefitting the world, since a career in the rabbinate would have detracted from his writings!

R. Wolpin also said that he had asked R. Mordechai Gifter whether R. Kaplan should write for the Jewish Observer, and R. Gifter responded that they should grab him up before the Conservative Movement makes him an offer on a silver platter!

I remember asking a relative of mine who also was at the lecture and knew R. Kaplan, whether he found the R. Gifter story to be insulting to the memory of R. Kaplan (he didn’t). Upon further thought, it shows R. Gifter’s openness, in that he knew R. Kaplan was an “out of the box” thinker, which was precisely why he wanted him to write for the Jewish Observer (one can see the JO website for RAK’s articles; my above recollections of R. Wolpin’s speech would seem to jive with the background from Prof. Alan Brill’s 2012 posts on R. Kaplan’s early days in the rabbinate).

As an aside, my relative also remembers hearing Rav Gifter speak at a Columbia University Yavneh event (men and women on separate sides) and described him as dazzling the audience. On the same day, he saw R. Gifter in a Midtown restaurant (roshei yeshiva apparently need to eat, too). R. Gifter was on Yavneh’s National Advisory Board according to Dr. Yoel Finkelman’s review article in the Torah u-Madda Journal (“History and Nostalgia: The Rise and Fall of the Yavneh Organization”).

That kind of ties in to my first comment above. Per Wikipedia, RAK was not brought up in a religious home and his rabbinic postings were all in non-Orthodox synagogues (though he was presumably personally Orthodox at the time).

I think it makes sense to assume that RAK wrote the material posted here at a different stage in life and environment and religious approach, which he later deliberately moved away from. Posting this material as if it represents the thoughts of RAK, on par with his published material, is inappropriate and does not do good things for either history or RAK’s legacy.

The Friday night lecture series in Bnei Yehuda were organized by my father, Rabbi Dr. Reuben Rudman.

Thank you for this information.

We might in fact both be correct. The Friday night lecture series in Bnei Yehudah was around since the ’90s. Your father, I’m assuming, founded and organized the lectures in its early years. In more recent years, I seem to remember R. Kirzner thanking Dr. Schick at the lectures for his involvement . R. Kasnett was also involved in the more recent lectures.

The shiurim were around in the 70s already. By the 90s my parents were no longer in Boro Park. This must have been a revival/continuation of my father’s project.

For those who didn’t know the story, it might be best to mention that Rabbi Adler’s murder was not some random act or anti-Semitic attack; he was killed by a congregant, a young man he knew well, who was probably at least somewhat unbalanced and who felt that American Jews, and this synagogue in particular (and of course its rabbi) were not living up to the proper standards in various ways. You can read an article by Rabbi Adler’s grandson (the comments add more) here:

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/my-grandfathers-assassin-and-me/

This reminds me of a question I’ve long had; maybe you two could shed some light on it: The Handbook of Jewish Thought had about sixteen chapters. The posthumous second volume had another twenty plus, but the introduction clearly says that the two volumes were drawn on a series of essays that included two more essays. (I don’t remember the exact numbers, but it says something like forty total and the second volume has twenty-two, or something like that.)

So my question has always been, what were the other two chapters? Why were they left out? Were they super-controversial? Were they regular, and there was just some prosaic reason for not including them- say, they’d already been published, or were too long? Were they published before or after this?

I also noticed that between the original and current printings, there’s a subtle omission in the summary on the back cover- a few sources of R’ Kaplan’s ideas are omitted (I think kabballah, philosophy, chassidut, and another), presumably for “frum” reasons.

“So my question has always been, what were the other two chapters?”

There is a third as well.

Prof. Alan Brill discussed this on his blog in October of 2019(“Aryeh Kaplan on Evolution- A Missing Chapter of The Handbook of Jewish Thought”) which was linked at the beginning of this Seforim Blog post:

“Update: There were three drafts of the book, 1962, 1968, and 1979. This chapter was already removed by Kaplan in the 1968 version. The family did not want this chapter published and it seems the widow was advised not to publish it by Rabbi Nosson Scherman. The 1962 edition had 41 chapters so the published handbook left out three chapters. The 1968 version was 40 chapters, which I called the original in the above post. Then there was a 13 chapter version in 1979, which became volume I”

Thanks! So apparently, though, there are still two unknown chapters missing, presumably fof ideological reasons.

Thank you to the esteemed authors for their good work and erudition, as always. Rabbi Kaplan is a fascinating genius and independent thinker.

Seforimblog readers may also find interesting one of his lesser known Hebrew works, Moreh Ohr, published posthumously from manuscript in the 1990s. It is available at:

https://www.docdroid.net/u73eqeo/moreh-ohr-aryeh-kaplan-pdf

The book elucidates a several topics in Jewish thought, דברים העומדים ברומו של עולם, and does so in an unusually clear manner, further highlighting the breathtaking talent and genius of Rabbi Kaplan.

He stands among a small cadre of outstanding personalities who passed away young and of whom one can speculate that had he lived to a ripe old age no one can quite tell how he might have immeasurably further enriched Jewish heritage or more fully entered the pantheon of Jewish leadership.

Professor Brill, if you’re reading this – thank you for all your work combing through old newspapers and other items to establish the history. Having read your very interesting blog posts and the longer article linked above in fn 1, one question nags at me, and I’d like to hear your thoughts if you don’t mind: To what extent is the Kabbalistic side of RAK a creature of the 1960s?

In your longer article there are frequent references to tripping and Timothy Leary, not to mention swamis and Buddishim, that I daresay do not resonate to anyone under the age of 65. Kabbalah in general is clearly on the wane, along with spirituality in general in the world. זה לעומת זה, one might say. (And in the orthodox world, spirituality is expressed primarily through prayer and study and even scholarship, exceptions duly noted.) It is hard to imagine this side of RAK – as opposed to many other of his enduring classics – being taken seriously in our world today. Do you have any thoughts you could share on this?

I think it’s safe to say that his article on avoiding the draft was very much a late 60’s thing.

I do not claim to be a “bar plugta” of RAK z”l (of whom I am a huge fan and admirer of.) Also, I was not able to read the entire image of his typed article.

However, given that #2 is tredding on ch”v disbelief in one of the 13 Ikrim, I will comment that the Rambam in his Peirush HaMishnaiyus Sanhedrin Perek Cheilek is not disputing the resurrection at Techiyas Hameisim, rather he is just saying that is not what the Mishna there is referring to. – There is a machloikes among many of the Roishoinim in this, if the first Mishnah of Cheilek is referring to the resurrection of Techiyas Hameisim or to the heavenly oilam haba. The Rambam and those that understand it to mean the heavenly oilam haba are not disputing the very fact of a resurrection.

#3 is also highly problematic, to say the least, since avoidah zarah or shituf is assur for goyim as well.

Also, with nevuah having long ended for Yidden, is that even plausible that it remained for goyim? Actually, there might be a sevora for that. Yidden fell from their higher position, goyim did not. The Vilna Gaon in Mishlei explains a pasuk that a goy without Torah can be an Adam, however a yid without Torah becomes more of a beheimah.

Preliminarily, as I understand it, he’s telling Christians that Judaism doesn’t care if J performed supernatural acts. He importantly sets up a boundary that the truth or falsity of such things should not affect Jews vis-a-vis Christianity. Jews should no accept or reject Christianity based on that belief… They should reject it regardless as it is not for them an they should not be persecuted by Christians for that rejection. Brilliant given the state of affairs of interfaith dialogue. This is in the same vein (though different of course) as Shmuley Boteach’s more recent work.

At any rate, no reason to believe R’ Kaplan ever personally believed such a thing. But such a belief would not be heresy.

As to the substance, I assume you’re comparing it to bilam harasha. Of course it’s slightly different because J was Jewish. But let’s say someone more recently, like Bahai (please don’t be offended by the absence of apostrophes). I don’t think that you would need to say that the Bab or whatever reached the level of nvua to say that hashem can send ideas to people that make them change the way they would act. Indeed hashgakha pratit must/may act this way in some part when it comes to directing human action. Or he was just nuts. 😉

Seems from his answer to q 14 that he didnt have access to an uncensored version of Mishneh Torah see Hilchos Melachim 11 4 אֲבָל מַחְשְׁבוֹת בּוֹרֵא הָעוֹלָם אֵין כֹּחַ בָּאָדָם לְהַשִּׂיגָם, כִּי לֹא דְּרָכֵינוּ דְּרָכָיו, וְלֹא מַחְשְׁבוֹתֵינוּ מַחְשְׁבוֹתָיו, וְכָל הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלּוּ שֶׁלְּיֵשׁוּעַ הַנֹּצְרִי וְשֶׁל זֶה הַיִּשְׁמְעֵאלִי שֶׁעָמַד אַחֲרָיו, אֵינָן אֶלָּא לְיַשֵּׁר דֶּרֶךְ לַמֶּלֶךְ הַמָּשִׁיחַ ולתַקֵּן אֶת הָעוֹלָם כֻּלּוֹ לַעֲבֹד אֶת י״י בְּיַחַד שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר כִּי אָז אֶהְפֹּךְ אֶל עַמִּים שָׂפָה בְרוּרָה לִקְרֹא כֻלָּם בְּשֵׁם י״י וּלְעָבְדוֹ שְׁכֶם אֶחָד. כֵּיצַד? כְּבָר נִתְמַלֵּא הָעוֹלָם כֻּלּוֹ מִדִּבְרֵי הַמָּשִׁיחַ וּמִדִּבְרֵי הַתּוֹרָה וּמִדִּבְרֵי הַמִּצְוֹת, וּפָשְׁטוּ דְּבָרִים אֵלּוּ בְּאִיִּים רְחוֹקִים וּבְעַמִּים רַבִּים עַרְלֵי לֵב, וְהֵם נוֹשְׂאִים וְנוֹתְנִים בִּדְבָרִים אֵלּוּ וּבְמִצְוֹת הַתּוֹרָה, אֵלּוּ אוֹמְרִים מִצְוֹת אֵלּוּ אֱמֶת הָיוּ וּכְבָר בָּטְלוּ בַּזְּמַן הַזֶּה וְלֹא הָיוּ נוֹהֲגוֹת לְדוֹרוֹת. וְאֵלּוּ אוֹמְרִים דְּבָרִים נִסְתָּרִים יֵשׁ בָּהֶן וְאֵינָן כִּפְשׁוּטָן וּכְבָר בָּא מָשִׁיחַ וְגִלָּה נִסְתְּרֵיהֶם. וּכְשֶׁיַּעֲמוֹד הַמֶּלֶךְ הַמָּשִׁיחַ בֶּאֱמֶת וְיַצְלִיחַ וְיָרוּם וְיִנָּשֵׂא, מִיָּד הֵם כֻּלָּם חוֹזְרִים וְיוֹדְעִים שֶׁשֶּׁקֶר נָחֲלוּ אֲבוֹתֵיהֶם וְשֶׁנְּבִיאֵיהֶם וַאֲבוֹתֵיהֶם הִטְעוּם:

Shalom I would really appreciate if you would would take this article off your blog . I would like to speak to you . Chaim Kaplan the youngest son of Rabbi Kaplan

I really would like to know if you had written permission to take these papers from my parents house ? I for sure did not give you permission . I think if my father was alive he could have answered all the questions . Also these papers were around for years before he was nifter and he did not print them . Maybe he had good reasons that he chose not to ! Please take this article off your blog ASAP. Thank you Chaim Kaplan

“It is true that some have not been convinced by the Letter on Resurrection and see it as an work letter that does not give us Maimonides’ true view, but such an approach means that one is accepting a significant level of esotericism in interpreting Maimonides, as we are not now concerned with a passage here or there but with an entire letter that one must assume was only written for the masses.”

What is ‘an work letter’? Is there a typo here?