Mysteries of the Magical Fifth Passover Cup (II): The Great Disappearing Act

Mysteries of the Magical Fifth Passover Cup (II): The Great Disappearing Act

By Leor Jacobi

Years ago, as a Yeshiva Bochur, a Rabbi explained to me that, according to the GRA, the Cup of Elijah at the Passover Seder is really the Fifth Cup mentioned in the Talmud which there is a doubt about Thus, it is Elijah’s cup because when he returns to herald the redemption, every Talmudic tequ will be solved. I found that the elusive Fifth Cup is not actually mentioned in the Talmud as we have it, but by most of the Rishonim, who all had a textual variant.

Later, as a Junger Mann, I found R. Menachen Mendel Kasher’s pamphlet on the Fifth Cup, also published in his Haggadot (generally abridged). Despite some intrinsic flaws, it is a masterful and ingenious integration of traditional and modern methods.

A few years ago, groundbreaking publications by my teacher, David Henshke, and my colleague, Eliezer Brodt, inspired me to build upon their foundation, concentrating on points which remain obscure or unsolved.

As there are quite a few of these, I divided up the study into seven chronological and thematic parts which I hope will evolve into book chapters eventually but also stand alone as they are. The first part of the envisioned series, on the magical genesis of the fifth cup, was accepted by a prominent journal that graciously agreed to have an early draft distributed here. Part four, on 19th century scholarship post-Levinsohn was recently submitted to another leading academic journal.

With the current social upheavals due to the Coronavirus pandemic in mind, thanks to the generosity of the editors of the Seforim Blog, we can forego delays and release a draft of part two in time for Passover. Hopefully, the virus will disappear faster than the fifth cup did! Please favor me with your feedback towards advancing the project and I will do my best to acknowledge any and all contributions.

In a previous study on the genesis of the Fifth Cup, a primary textual variant of the Babylonian Talmud (Pesachim 118a) was identified as the source, an original teaching from the Talmudic Sages. Following the compilation of the Talmud, Babylonian Geonim not only received this textual variant, but actually drank the fifth cup themselves, with the apparent exception of Rav Hai Gaon, who also had the fifth cup Talmudic variant, but interpreted it as an optional practice, one which he did not follow. If the fifth cup was ordained in Babylon due to zugot, concern for even pairs arousing evil spirits, as explained in the prior study, perhaps Rav Hai inherited the original Palestinian custom of only four cups (zugot was only an issue in Babylon), as the Sages of Erez Israel did not believe in zugot. Alternatively, perhaps Rav Hai rejected the fifth cup as far as his own practice but not to the point of speaking out against it.

The fifth cup was widely observed among the Babylonian Geonim, and subsequently mentioned by Alfasi, Maimonides, and by Tur (14th century), the latter at length, with an entire siman (OḤ 481) devoted to it.

However, if we fast-forward to the 16th century, we find that, despite an extensive discussion in R. Joseph Karo’s monumental Bet Yosef the fifth cup disappeared completely in his Shulḥan Arukh. Following the order of Tur, R. Karo gave names to all of the simanim. Here, he adopted a side issue of the siman and made it the focus and new title: “Not to drink after the fourth cup”.

Furthermore, none of the principal commentators on the Shulḥan Arukh (“nose kelim”, 16th-17th centuries) even noted its disappearance. Explaining the magical disappearing act of the fifth cup during the Middle Ages will be the focus of this study.

The disappearance has bothered modern scholars of rabbinic literature, who struggled to explain it, most notably R. Menahem Kasher. Several factors have been suggested to explain the elimination of the fifth cup. They include: 1) Deletion of the Talmudic text mentioning the fifth cup due to homoteleuton (skipping text from one similar word to another)[1], 2) Endorsement of this variant by Rashi and Rashbam, 3) Application of this variant by subsequent Ashkenazi scribes,[2] 4) Circulation of an abbreviated version of Rav Hai Gaon’s responsum (in Tur) which suggests that Rav Hai Gaon also received the “Rashbam’s” version of the Talmud which does not mention the fifth cup,[3] 5) A statement at the beginning of Tur that the fifth cup should not be drunk, probably explaining Rashbam’s opinion, but ambiguously stated, 6) the development of a stringency in Medieval Ashkenaz to refrain from all drinking after the fourth cup, with some including even water in the prohibition (see below) and 7) The publication of the Venice edition of the Talmud, in 1520-23 following Rashbam’s textual variant, with no mention of the fifth cup, all subsequent editions following in kind, almost certainly the edition consulted by R. Joseph Karo.

Despite this multitude of factors, they don’t adequately explain R. Joseph Karo’s editorial decision to completely delete such a well-entrenched custom as the fifth cup, mentioned by all three of his pillars, Alfasi, Maimonides, and Rosh.[4] I propose that an additional factor, barely recognized previously and never noted in this context, was the one that settled the matter conclusively in the mind of Maran.

Rabbenu Yonah Girondi (13th century) maintained that one should refrain from drinking extra wine so as to be able to study the laws of Passover and the story of the Exodous all night, as the Sages did in Bne Braq. Maharil cites Rosh (Asheri) as adding that the fifth cup was permitted due to the verse v’heveiti. However, our standard printed text of Rosh states that the fourth cup is permitted due to the verse v’laqaḥti.

(אבל בכוס רביעי התירו שיש לו סמך מן הפסוק כנגד ולקחתי אתכם. (סימן לג…

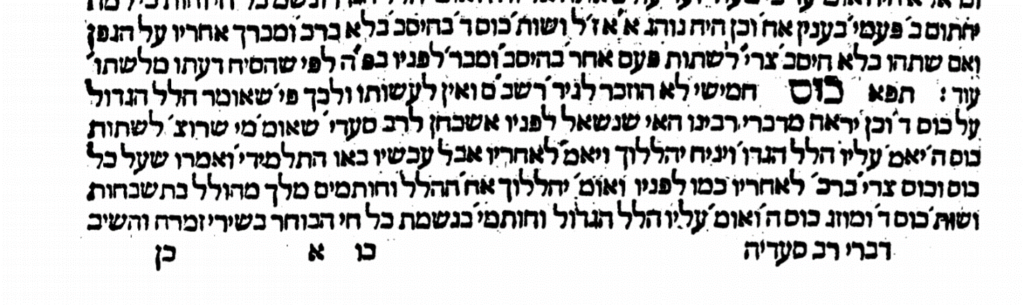

Rabbi Alter Hilewitz (1906-1994, author of halakhic works and editor of Encyclopedia Talmudit) objected that the printed text makes no sense and must have become corrupted.[5] There is no reason to permit the fourth cup after it has already been mandated in the Mishnah. The special dispensation must have been for the fifth cup and Maharil cited the genuine text version of Rosh.[6] R. Hilewitz’s hunch was correct, as we find in an early manuscript of Rosh (Asheri) written in Spain in 1325 during the lifetime of Rosh (from middle of 3rd line from bottom):[7]

Rabbi Hilewitz

The corruption was a by-product of proliferation of the Rashbam’s text of the Talmud eliminating the fifth cup entirely. It probably represents an unintended stringency in interpretation of the prohibition on drinking excessively. Another correction we find in the manuscript is the attribution of the opinion. The manuscript attributes it to Rabbenu Yonah, corresponding to the attribution in Tur. However, the printed edition misattributes it to ר”מ, R. Meir of Rothenburg, master of Rosh.

The text of Rosh which R. Joseph Karo relied upon was almost certainly that of the famous aforementioned Venice edition of the Talmud.[8] It reads:

.אבל בכוס רביעי התירו שיש לו סמך מן הפסוק כנגד והבאתי אתכם…

The text does not make sense. It is conflated. Either the fourth cup was permitted by the verse v’laqaḥti (as in the modern printed editions), or the fifth cup was permitted by the verse v’heveiti (as in the manuscript). The fourth cup could not have been permitted by the verse v’heveiti. The development was apparently a two-stage process and the Venice Edition represents the “missing link”, an intermediate stage in which the fifth cup was changed to the fourth cup but the verse remained intact. At this point, R. Joseph Karo or the later publishers could have corrected the text back to “the fifth cup”, restoring the original version in the manuscript. However, the tide was already turning towards the fourth cup Talmudic textual variant in Bet Yosef, with his decision to read Rashbam’s Talmudic textual variant into Rav Hai Gaon’s responsum.[9] R. Joseph Karo decided to keep “the fourth cup” and to ignore the word v’heveiti, or to mentally “correct” it to v’laqaḥti, exactly how the later printers chose to emend the text of Asheri.

One can speculate as to why Kasher, Benedict and subsequent Rabbinic scholars did not discover this source. R. Hilewitz’s observation was published in a 1945 newspaper article in Palestine. At the time, war was raging and R. Kasher was in America. Manuscript variants of the text of the Talmud have been studied and published on for years[10] and the last generation has brought us two editions of Tur prepared using manuscripts.[11] Even Tosafot Rosh is published from manuscripts in critical editions.[12] However, for some reason, manuscripts of Rosh are relatively uncharted territory, despite the centrality and rabbinic authority of the work. Perhaps (similar to Rashi’s Talmudic commentary, up until the groundbreaking work of my teacher, Aaron Ahrend) it is this very centrality that led its manuscripts to be ignored, as it was printed so early on, in the Venice Talmud, and so many times.

Most significantly, the text is hidden from view. Tur clips off this section of the discussion and Bet Yosef does not cite it. However, once we return to the textual version that laid open before R. Joseph Karo on his desk, which he certainly meditated on, we can understand how he interpreted the abbreviated text of Tur and why he decided to delete the fifth cup.

Addendum: The Power of Piyyut

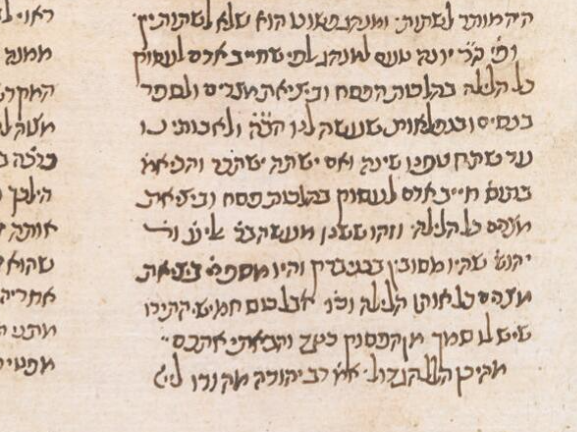

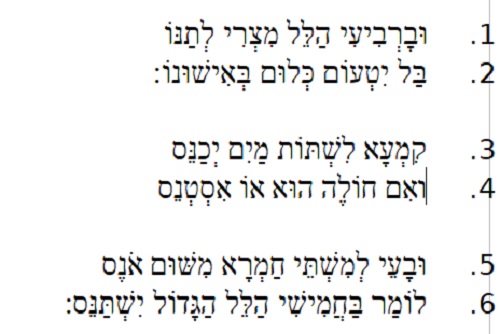

Shmuel of Evreux adopted a stringency not to drink even water after the four cups.[13] His source was the piyyut composed by R. Yosef Tuv Elem for a qerova recited on Shabbat ha-Gadol.[14] The last two stanzas at the end of the piyyut are the most famous today, for they are recited almost universally at the end of the Haggadah: “Hasal siddur Pesah”. The stanza preceding it is one mentions the fifth cup. There are two textual variants of this line interpretations of the piyyut. Three manuscripts read as follows:[15]

According to this text, line 3 states that it is permitted to drink water absolutely, in accordance with normative halakhah. Line 4 adds conditions for drinking wine, being sick or finicky, as described in line 5 with the recitation of Hallel ha-Gadol in line 6.

Medieval piyyut commentaries also follow this text, for example, the commentary by Samuel b. Salomo of Falaise:[16]

…קמעא, מעט, לשתות מים יכנס, לאחר סעודתו אם ירצה לשתות, ואם חולה הוא או אסטניס ובעי למשתי חמרא ואינו יכול לשתות מים, לומ’ בה’ על שם ‘ה הלל הגדול, ישתנס, יאזור

However, the textual variant followed by the Tosafot (Pesahim 117b) omits the vav at the beginning of line 4. Now the conditions of line 4 apply to line 3 as conditions for drinking water. Apparently from this piyyut, R. Shmuel of Évreux derived the stringency against drinking water after the Seder.[17] Tosafot for chapter Arvei Pesahim were based upon the Tosafot of R. Yechiel of Paris or a student of his, such as Rabbenu Peretz (Shalem Yahalom). R. Yechiel was in contact with R. Shmuel. R. Yechiel would attempt to refute R. Shmuel’s novel stringencies. Sometimes the refutation was accepted, such as cited by R. Peretz in his gloss to Smak 93, and sometimes not, as found in Orhot Hayyim, Hilkhot Tum’ah, vol 2, p. 602, and apparently in our case regarding the stringency of not drinking water. In this case, the development of a stringent shitta forbidding even the drinking of water likely shifted the goalposts of halakhic discussion away from the option of the Fifth Cup of wine.

Finally, on the topic of piyyut, Leon J. Weinberger described a poem from R. Binyamin which mentions the fifth cup as a basic custom, an integral part of the Passover Seder. The piyyut was later published in its entirety by Ezra Fleischer.[18] According to Weinberger, it provides a messianic interpretation of the fifth cup, an aspect of the fifth cup that will become more evident during later periods to be discussed in chapters of this study yet to come.

Editor Note: please see Eliezer Brodt’s earlier post on this subject: https://seforimblog.com/2013/03/the-cup-for-visitor-what-lies-behind/

[1] Henshke; also see here for another possibility and analysis of Talmudic manuscripts here.

[2] Kasher noted Rabbenu Tam’s fierce opposition in general to applying proposed emendations into the text of the Talmud itself, blaming Rashbam (his older brother) in particular. See Spiegel, Soloveitchik, briefly reviewed in my Jewish Hawking in Medieval France.

[3] Rav Kasher advanced this claim convincingly to explain the deletion by R. Joseph Karo. R. Avraham Benedict also advanced this claim, without crediting Kasher. As far as rendering a legal decision, Benedict took a diametrically opposite position. According to Kasher, now that we possess the full version of Rav Hai Gaon’s responsum, we see that R. Joseph Karo was led astray by an ambiguous text. Benedict considers R. Karo’s decision binding and the presence of the abbreviated version is ample justification.

[4] Noted especially by Kasher, also by Henshke.

[5] ‘Kos shel Eliahu’, Bamishor 245-6 (25.3.1945), p. 5.

[6] This version is also found in Abudraham (Seder ha-Haggadah u’Perisha, ed. S. Kroizer, Jerusalem 1963, p. 234), citing Rabbenu Yonah. Abudraham’s source was probably Asheri, but he did not generally cite secondary sources, as he himself stated in his introduction (p. 6.). See: L. Jacobi, “Talmudic Honey”, Fragments of the Novellae of R. David ben Saul of Narbonne”, Giluy Milta B’alma, 2/17/2016.

[7] British Library Add. 27293 f. 131v.

[8] Bomberg: Venice 1520-1523, p. 138b.

[9] Kasher, Benedict.

[10] Diqduqe Sofrim, Lieberman Instritute, Friedberg.

[11] Shirat Devorah; Ma’or.

[12] Mossad Ha-Rav Kook, Ofeq Institute.

[13] Cited by Mordechai, Hagahot Maimoniot (Ed. Constantinople, 6:11, “gedole Evreax”), Agur. Tosafot Pesachim 117b.

[14] See a letter from Pinchas Eliyahu Lawee in Kobetz Beit Aharon 15:5 (89, 1998), pp. 135–136.

[15] With only minor variants irrelevant for our purposes. Gabriel Wasserman shared with me his pilot edition of variants and Abraham Levine provided me with expert guidance in this study.

[16] Parma – Biblioteca Palatina Cod. Parm 3000 (de Rossi 378), f. 30a-35b. I was aided in locating piyyut commentaries by Elisabeth Hollender’s monumental Clavis.

[17] Another later piyyut follows this strict opinion, recently published by R. Jacob Israel Stal. See his note at page 33.

[18] Kobez al Yad 21 (1985), p, 31.

22 thoughts on “Mysteries of the Magical Fifth Passover Cup (II): The Great Disappearing Act”

Haggadat Hapesah recommends following Maimonides’s suggestion to drink a fifth cup.

Maimonides does allow for the drinking of the fifth cup; however, he himself did not drink the fifth cup according to the testimony of his son, R. Abraham, in a manuscript fragment preserved in the Ma’aseh Roke’ah commentary (p. 251a).

I’m not claiming that it is a proof, but this would be consistent with Rambam interpreting the fifth cup mentioned by the Talmud as pertaining to zugot and demons.

I’m delighted you quoted my maternal grandfather, Rabbi Alter Hilewitz. He was a prolific and brilliant scholar but doesn’t get quoted much by name on the internet, and I have certainly never seen a photograph of him posted (where did you get that from?).

Could I ask you to fix the spelling of his last name? Thank you so much.

Yael

Hi Yael,

I’m glad Leor and we could delight you by mentioning your grandfather.

The photo is a screen capture from this video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSFK9V8YBBc

If this is new to you, all the better. To help you in finding more about him, Googling him in Hebrew, “אלתר הילביץ”, seems to help.

Will make the spelling correction.

Wow, thanks so much. I had no idea that video existed. So great to see his face again.

Rav Alter Hilewitz’s original article Koso Shel Eliyahu is reprinted verbatim in vol.2 of his book Chikre Zemanim (Mosad Harav Kook, 1981) p. 108-111. He mentions in a footnote that it was published a long time ago and since then Kasher had published a detailed study of the fifth cup. Perhaps he was not completely satisfied with Rav Kasher’s study and that is why he republished his original unaltered.

It’s a short newspaper article, as opposed to Rav Kasher’s sweeping survey. Maybe there are some more unique nuggets there!

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.

I simply want to tell you that I am just newbie to blogging and certainly liked you’re blog. Probably I’m want to bookmark your site . You surely come with awesome articles. Many thanks for revealing your webpage.

You should be a part of a contest for one of the most useful websites on the net. I’m going to highly recommend this web site!

I was able to find good information from your articles.

Howdy! This article couldn’t be written much better! Reading through this article reminds me of my previous roommate! He always kept preaching about this. I will send this post to him. Fairly certain he will have a very good read. Thank you for sharing!

I want to to thank you for this fantastic read!! I absolutely enjoyed every bit of it. I have got you saved as a favorite to check out new things you post…

Very good post! We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing.

Do you believe in your past life? Do you think past lives regression is real?

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something which helped me. Kudos!

멋져요 https://www.wooricasinokorea.com/baccarat 바카라사이트

I merely wish to advise you that I am new to posting and extremely adored your review. Likely I am inclined to store your blog post . You simply have memorable article material. Get Pleasure From it for share-out with us all of your internet page

win money software

win ferrari

A fascinating discussion is worth comment. I do think that you need to write more on this subject matter, it may not be a taboo matter but generally folks don’t speak about these issues. To the next! All the best!