Apostates and More, Part 2

Apostates and More, Part 2

Marc B. Shapiro

Continued from here

1. Another apostate was Rabbi Nehemiah ben Jacob ha-Kohen of Ferrara, who was an important supporter of R. Moses Hayyim Luzzatto during the controversy about him.[1]Here is the the final page of the haskamah he wrote in 1729 for R. Aviad Sar Shalom Basilea’s Emunat Hakhamim.

R. Isaac Lampronte, in a halakhic discussion in his Pahad Yitzhak, refers to Nehemiah, but not by name.[2] He calls him אחד מן החכמים רך בשנים אשר אחרי כן הבאיש ריחו כנודע. In R. Hananel Nepi and R. Mordechai Samuel Ghirondi, Toldot Gedolei Yisrael (Trieste, 1853), p. 229, they write about Nehemiah: שאח”כ נעשה ישמעאלי. Obviously, “Ishmaelite” is a code word for Christian.[3]

The story reported by Samuel David Luzzatto is that Nehemiah used to go to prostitutes, and when the rabbis found out about this they removed the rabbinate from him. Too embarrassed to remain in the Jewish community, Nehemiah apostatized.[4] Cecil Roth cites another Italian source that Nehemiah converted so he could marry a Christian woman. Unfortunately, his son and three daughters apostatized together with him (his wife had apparently already died).[5]

Another apostate who should be mentioned is Michael Solomon Alexander (1799-1844), first Anglican bishop in Jerusalem. Before his apostasy, Alexander was a rabbi.[6]

Rabbi Abraham Romano of Tunis also became an apostate. He converted at the end of the seventeenth century when R. Meir Lombrozo was appointed a dayan in his place. After Romano converted, he became well known as a Islamic preacher, and after his death his tomb was venerated by Muslims. He was known as Sidi Sofiane, and the street in Tunis with this name is named after him.[7] It is reported that in the nineteenth century R. Uziel Alheikh, author of the halakhic work Mishkenot ha-Ro’im, would recite Kaddish at Romano’s grave so God would forgive his sin.[8]

I am sure many readers have heard of Rabbi Israel Zolli, the chief rabbi of Rome who converted after the Holocaust. Not so well known is Rabbi Daniel Zion, who was the chief rabbi of Bulgaria and after World War II served as a rabbi in Jaffa. When it became known that he was a believer in Jesus, he was forced out of his rabbinic position. There is a good deal online about Zion, and entries in English and Hebrew on Wikipedia.

Rabbi Hayyim Asher Hoffmann was another modern rabbi accused of working with missionaries. He was in Argentina at the beginning of the twentieth century, and wrote a haskamah for R. Menahem Mendel Hirschhorn’s 1904 book Magid le-Yisrael. Here is the title page of the book, followed by the haskamah.

In 1907, R. Mordechai Amram Hirsch of Hamburg informed Jewish leaders in Buenos Aires that Hoffmann had worked in the Christian mission in Hamburg. Not long after this, Hoffmann committed suicide.[9]

Hoffmann is not the only rabbi to have committed suicide. In his recent article in Hakirah, Moshe Ariel Fuss deals with R. Moshe Soloveichik’s great dispute with the Polish Agudat Ha-Rabbanim. He also discusses the suicide of one of the dayanim of Tomashov, which was related to the dayan’s role in the dispute.[10]

There was another rabbi and author of a sefer who committed suicide. Let me preface this story with some other relevant information. In the early 1990s there was a project at the Harvard library to put thousands of rare Hebrew books on microfiche. This would then be sold to major university libraries. It was a wonderful idea and involved considerable expense on the part of the company, K.G. Saur, which was carefully photographing the books. (I used to watch the photographer doing his work.) It was very costly to purchase the more than ten thousand fiches, but for a library that wanted to instantly have access to almost five thousand rare Hebrew books, this was a great solution. You can see a 1994 ad for the project here.

Unfortunately for this project, advancing technology made it obsolete almost immediately upon completion. The ability to access rare books online, on hebrewbooks.org, Otzar ha-Chochma, Google Books, and other sites, meant that microfiche readers went the way of typewriters. (I still haven’t gotten rid of my own microfiche reader, as I never know if it might come in handy).

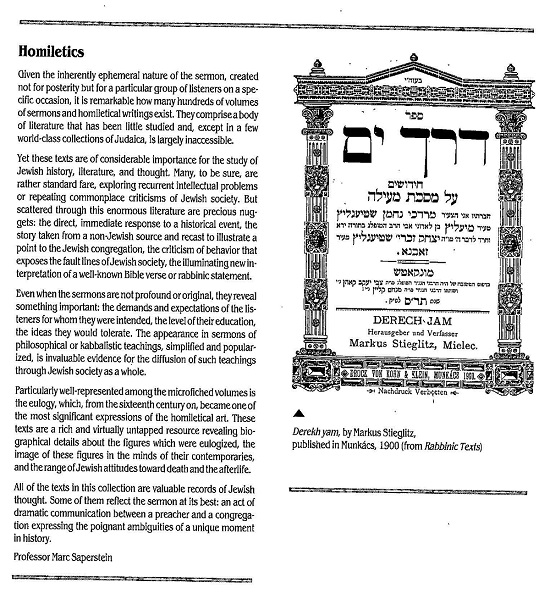

Harvard put out a catalog advertising the microfiche set, which discussed the different genres of books included. The catalog also had pictures of a few of the title pages of the books. Here is one of the pages in the catalog.[11]

Here is a clearer picture of the title page.

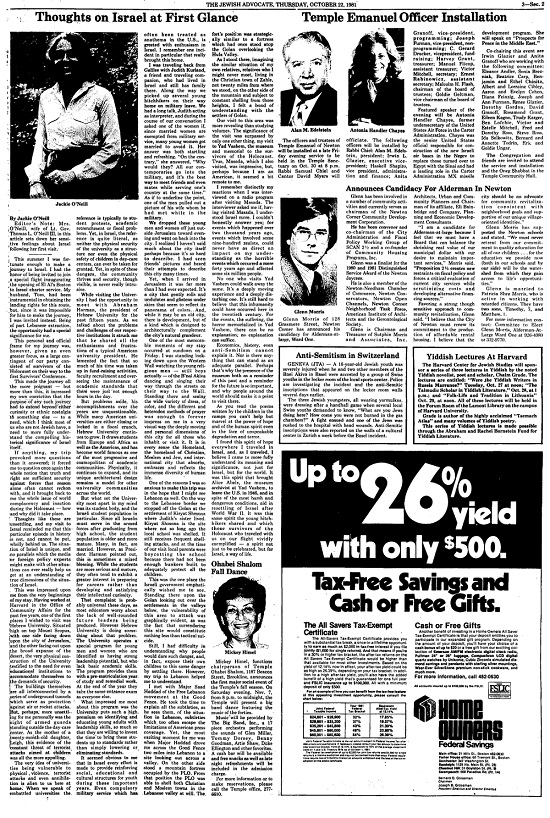

The book is Derekh Yam on Tractate Meilah by Rabbi Mordechai Nahman Stieglitz, published in 1900. At the time (almost thirty years ago), I thought nothing of this, and just assumed that Derekh Yam was a random book that was picked for inclusion in the catalog. However, someone who knows a lot about seforim told me that there is no question that Derekh Yam was not randomly picked. He said that whoever chose to use this title page, when there were so many others that could have been picked, must have done so as an inside joke for the benefit of those who knew the history of Rabbi Stieglitz (which at the time I knew nothing about).

Derekh Yam is a fine commentary on a tractate that not so many have written about. Understandably, then, when people study Meilah this is one of the books they will turn to. And why not, seeing that the book has haskamot from such great figures as R. Isaac Schmelkes, R. Shalom Mordechai Schwadron, and R. Aryeh Leibush Horowitz? It also includes an approbation and a lengthy responsum (pp. 47a-58a) by R. Joshua Horowitz, the Rebbe of Dzikov (Stieglitz’s hasidic group[12]) and author of a number of volumes with the title Ateret Yeshuah.

Shortly following the appearance of Derekh Yam, Stieglitz’s life took a different turn. He not only left Poland but abandoned Torah observance as well. Meir Wunder writes that “he went to study at the University of Berlin (and not Vienna).”[13] Wunder’s information that Stieglitz studied in Berlin presumably came from Yehudah Rubenstein (see below), but I don’t know why he felt the need to correct the error that he studied in Vienna, as I haven’t seen anyone make this claim.

It could be that Stieglitz did study in Berlin (though I know of no evidence for this), and to be sure one would need to check the archives of the University of Berlin. However, Rubenstein and Wunder were unaware that Switzerland was Stieglitz’s primary academic place of study, and his 1908 doctoral dissertation is from the University of Bern. It deals with Baraitot in Tractate Berakhot in the Bavli and Yerushalmi. You can see it here. As was typical in those days in Germany and Switzerland, the doctoral dissertation is short and insignificant. It never ceases to amaze me how easy it was in those countries to receive a doctorate.

Yehudah Rubenstein says the following about Stieglitz:[14] When his book Derekh Yam appeared it was greatly praised by Torah leaders and had an impact on talmudic scholars. It also included a long responsum from R. Joshua Horowitz. Later, a רוח שטות entered Stieglitz and he abandoned his wife and children and went to Berlin to study, where he abandoned Torah observance and fell in love with the daughter of a banker, whom he married after divorcing his wife. He then went to New York where he went into business and made a lot of money on Wall Street. However, during the Depression Stieglitz lost his money and committed suicide.[15]

Rubenstein also notes that Dzikover hasidim, at the command of their rebbe, collected all the copies of Derekh Yam that they could find, from synagogues and private homes, and destroyed them. He concludes:

.והספר דרך ים הוא יקר המציאות, כי נשארו ממנו טופסים מועטים

What used to be a rare book is now, thanks to modern technology, at everyone’s fingertips. Even if, as a result of this post, the book is removed from hebrewbooks.org and Otzar ha-Chochma, you can still see Harvard’s copy here.

In 1976, the descendants of R. Joshua Horowitz published Ateret Yeshuah: Likutei Teshuvot ve-Haskamot.

In the introduction it states that the book includes all the responsa and approbations of R. Horowitz found in the writings of others. However, they purposely did not include the approbation and responsum found in Derekh Yam.[16]

Returning to apostasy by rabbis who produced seforim, I have previously mentioned R. Profiat Duran, the Efodi (see here), and an article by Joseph Hacker has recently appeared which further complicates matters.[17] Let me first note that in Latin documents his name appears as Perfeyt, so from now on this is how I think we should pronounce it. Second, and here Hacker follows on Maud Kozodoy’s earlier research,[18] we have evidence that not only did Duran convert (this we already knew), but that he remained a Christian for the rest of his life, even when he had left Spain and could have returned to Judaism. If that wasn’t enough, both Kozodoy and Hacker believe that he married a Christian woman, as the wife to whom he left his possessions had a different name than his first wife. Yet this latter point is not conclusive. It could be that the woman he was married to at the end of his life was a Jewish woman who apostatized, either the original wife who changed her name on conversion, or a second wife. How Duran continued to write anti-Christian polemical works while living as a Christian is still a mystery.[19] His famous grammatical work, Ma’aseh Efod, the introduction to which Professor Isadore Twersky loved to study with his graduate students,[20] was also written while he was a Christian.

When the information about his life eventually filters out to the Orthodox world, presumably he will no longer be cited as an authority (although all evidence points to his important commentary on Maimonides’ Guide being written before his conversion so perhaps that can still remain in the canon).[21]

I must also mention R. Levi Ibn Habib (ca. 1480-1541), the great sage of Jerusalem. As a young man in Portugal, he converted (or was converted) to Christianity. We don’t know if at this time he was living with his father, R. Jacob Ibn Habib, who is famous for editing the Ein Yaakov. Later, R. Levi journeyed to Salonika where he was together with his father.

We do not know the precise details of R. Levi’s conversion. Scholars often write about Jews being subjected to “forced conversion.” This can mean that one is told he must convert or he will be killed. In this circumstance, Jewish law requires martyrdom, and Jewish history knows of many who chose this path.[22] Yet people who were not strong enough to accept martyrdom, and converted to Christianity to save their lives, are routinely described as forced converts.

The other meaning of forced conversion is using actual physical force to baptize someone, as occurred in Portugal. R. Levi was in Portugal in 1497, when Jewish life there came to an end. Many Portuguese Jews converted “willingly” – in addition to the strong Christian pressure to convert, some did so to be freed from slavery or after their children were taken from them, as this was the only way to get them back. There was also the unusual circumstance that the King ordered the Jews not yet baptized to be baptized against their will, literally by physical force. (Mainstream Catholic teaching did not regard this as a valid baptism, unlike the case of one who converted to save his life, as this latter act was taken out of free will).[23] As mentioned, we do not know whether R. Levi converted “willingly” or not, but we do know that he lived as a Christian after this conversion.

In the great dispute over the revival of semikhah between R. Levi and R. Jacob Berab, R. Berab saw fit to allude to R. Levi’s conversion as a means of discrediting him. This is quite surprising, as one is not supposed to remind a ba’al teshuvah of his previous sins. Here are some of R. Berab’s words which are clearly designed to contrast his pure history with R. Levi’s history, which included living as a Christian (and thus having a Christian name).[24]

שת”ל מיום הגרוש והשמד שבספרד לעולם הייתי מורה הוראות בישראל . . . ועם היותי ברעב ובצמא ובחוסר כל לעולם הלכתי בדרכי השם יתברך ונתעסקתי בתורתו . . . ות”ל שמעולם לא נשתנה שמי אי רבי קרו לי השתא רבי הווי קרי לי אז וזה שמי לעולם . . סוף דבר שת”ל לעולם השתדלתי שלא ילך להתרעם עלי שום אות מאלף ועד תי”ו, רצוני לומר שלא נתחלל שם שמים על ידי בשום אחד מהאותיות כדי שלא יעלו לשמים להתרעם עלי

R. Levi was understandably quite offended by R. Berab’s words. He expresses his pain that R. Berab would attempt to publicly humiliate him by bringing up the difficult timein Portugal. He makes it clear that he is speaking for many others who were also in his unfortunate circumstance.[25]

לישנא בישא טובא איכא הכא, ובמקום שהיה לו לחכם להודות על האמת ולהשיב כהלכה גרם לשפוך דמי ולהלבין פנים בהזכירו אלי עונות ראשונים . . . לא לכבודי ח”ו כי אם לכבוד כל אותם שנמצאו באותה הצרה ושמו עצמם בסכנות רבות וברחו ולא ראו בטובה עד שזכו להיות בעלי תשובה ורבים מהם נפטרו לחיי הע”ה

R. Levi also mentions that he was not yet a bar onshin when he converted. The evidence we have shows that he was older than 13 in 1497, so when he says that he was not yet a bar onshin, it must mean that he was under the age of 20. This is in accord with an aggadic statement in Shabbat 89b that God does not punish for transgressions in the first twenty years.[26] The Zohar, Bereishit 118b, also states that while an earthly beit din punishes from age 13, the Heavenly Court does not punish for sins committed before age 20.[27]

R. Levi further states that despite his difficult circumstances, in his mind he remained a Jew, loyal to the one true God. While others changed his name to a Christian name, he himself never changed. He adds that while he did not merit to die al kiddush ha-shem, he hopes to achieve a complete repentance for his past. Here are some of R. Levi words, full of pathos:[28]

ואומר כי אני לא אחלל בריתי ברית התורה להשיב לזה החכם על פי דרכו . . . גם לא אכחיש המובן מדבריו בהגדלת אשמתי ולא אציל עצמי בדברתי לומר שאף אם שנו שמי בעונתי בשעת השמד אני לא שניתי, ובוחן לב וחוקר כליות יודע כי תמיד אותו יראתי, ואם לא זכיתי לקדש שמו לבי יחיל בקרבי מפני זעמו הגם שעדיין לא הייתי בר עונשין בבית דינו כלל, מכל זה לא אומר ח”ו כי שקר התנצלותי, ועוד כי יוסיף פשע על חטאתי, אדרבה אבכה יומי ולילי אוי לי אללי ואודה עלי פשעי ואומר ידעתי יי’ רשעי ופשעי וזדוני כי רבו למעלה ראש משורש פורה רוש, ואשמותי גדלו עד לשמים, אבל בטחתי על רוב חסדיך ונשענתי על רוב רחמיך, וכשם שזכיתני לצאת מן ההפכה והבאתני אל העיר ההוללה בתוך השנה להיות שונה שם בכל יום הלכה עד היום שיש יותר מארבעים שנה, כך תזכני להיות בעל תשובה שלמה, ומה גם עתה בהיותי עולב עלבון גדול אשר כזה על לא חמס בכפי, ואתה אדון הסליחות אלדי הרוחות ראה בדמעות אשר זלגו עיני עתה באנחות ויהיו בבית גנזיך מונחות לעת צאת נפשי, ואולי תזכה בהן לשוב למנוחות

It is one thing for contemporaries to slug it out and attack each other. However, that was hundreds of years ago, and in the intervening centuries both R. Levi and R. Berab have been included in the canon of gedolim. R. Berab has the additional distinction of having given semikhah (the real kind) to R. Joseph Karo. As such, we are dealing with important figures who are each deserving of great respect. This is why I found it so unusual that a twentieth-century rabbi, Benjamin Trachtman, who came to the defense of R. Levi, showed considerable disrespect for R. Berab.

R. Trachtman was a rabbi in a few different places in the United States and Israel, and author of a number of works. In 1930 he was rabbi in Mishwaka, Indiana (near South Bend) when he published his book, Shevet Binyamin. Here is the title page.

The book comes with a number of “haskamot,” among them from R. Moshe Mordechai Epstein and R. Isaac Sher. From the “haskamot” we learn that R. Trachtman had been a student at the Chevron Yeshiva. I put the word haskamot in quotation marks, since even though that is what the letters at the beginning of the book are called, they are not haskamot at all as they have nothing to do with the book. Rather, they testify to R. Trachtman’s Torah knowledge and most of the letters are semikhah certificates.

I find it hard to believe that R. Trachtman’s teachers, and the others whose letters appear in the book, would have approved of his judgment of R. Berab, found on p. 93 of his book. He states that in looking at the dispute between R. Levi and R. Berab, you can see the difference between a person who has mussar values and one who is “lacking mussar and middot”! He claims that R. Berab is an example of someone who had great Torah knowledge but was lacking in the area of ethics. I find it incomprehensible that a twentieth-century scholar would speak this way about one of the recognized Torah sages of centuries ago.

משם יש לראות את הנפ”מ בין אדם בעל מוסר שכל דבריו שקולים במשורה בחשבון ודעת לאדם חסר המוסר והמדות, והינו[!] כי אחד מהדברים אשר אדם נכר בהם הוא בכעסו, בעת אשר מחלוקת לו עם חבירו, והנה המחלוקת של שני החכמים הנ”ל אם כי המחלוקת היה לש”ש לדינא אבל בכל זאת יש לראות שם גם זה הסוג מחלוקת של אנשים השוטים והמחלוקת מזה הסוג בולט הרבה מדברי הר”י בי רב, כי בדבריו אנו רואים התנפלות עזה בדברים בוטים כמדקרות חרב ועלילות מזויפות על הרלב”ח אשר א”א בשום אופן שמחשבון יצאו הדברים ואדרבה הרלב”ח אף כי גם הוא אינו מחריש לו אבל דבריו בנחת נשמעים במתינות ובישוב כנראה משם . . . ואל תאשימני על בואי לבקר את הר”י בי רב כי נתן לי רשות בדבריו, וסוף סוף אנו רואים בחוש גם עתה כי הוא שני דברים נפרדים כי יש למצוא תלמידי חכמים אשר גאונותם בתלמוד הוא עד למאוד וכשבאים לסוגיא “יכיר יכירנו לאחרים” הם נכשלים באופן פשוט אשר בשום אופן אין לחפות עליהם, אם לא כי יצאו מגדר המוסר

Also worth noting is Jacob Katz’s comment at the end of his classic article on the semikhah controversy.

Nor can we ignore the fact that Berab’s personal attacks on ben Habib, and the recounting of his “old sins,” were not germane. He did not dare to give explicit expression to the serious accusation about ben Habib’s conversion in his youth; instead he couched it in words of self-praise (“I myself never changed my name”). Such a tactic is evidence of an emotional need to pretend that one has done nothing wrong, which is a sign of an uneasy conscience.[29]

I must also mention R. Isaac Bar Sheshet, the great Rivash. Did the Rivash actually convert to Christianity during the anti-Jewish persecution of 1391? There is no mention of this in any Hebrew documents. However, in 1983 Jaume Riera published an article in Sefunot based on documents from the Spanish archives which show that during the 1391 anti-Jewish attacks, the Rivash, who served as rabbi of Valencia, converted to Christianity. This is attested to in three separate documents, two of which refer to the rabbi of Valencia and one of which identifies the Rivash by name. The documents show that while many Jews were killed in Valencia during the attacks, most converted to save their lives and the large synagogue was turned into a Church.[30]

We do not know the exact circumstances that supposedly led the Rivash to convert, and the only important detail in this regard that we learn from the documents is that the Rivash’s death sentence was revoked after his apostasy. Riera offers a suggestion to explain why Rivash chose to convert, but this is based on nothing other than Riera’s vivid imagination. Yet Riera’s imaginings, which conjured up “false witnesses,” a “disgraceful crime,” and other completely fictional events, are presented in the Wikipedia entry on Rivash as actual fact.

In 1391 there occurred the great persecutions of the Jews of Spain in consequence of the preaching of Fernandes Martinez. On the first day of the persecutions, the younger brother of King John I summoned Isaac on July 9, 1391. He explained that to be able to restrain and cease the bloodshed, it would be necessary to promulgate an organized conversion of the Jews, which should obviously start with the communal leaders. Some of the leaders did relent to the heavy pressure laid upon them; but not Isaac, who held steadfast to his faith. After a couple of days, the officials set up false witnesses to testify against Isaac for a disgraceful crime. Due to this accusation, Isaac was condemned to death, by burning at the stake in the city’s central square. On July 11 Isaac was immersed, donned the robe of a Dominican and received the name Jaume De-Valencia.

Around a year and a half after the supposed conversion the Rivash escaped to Algeria, where he was known as a great posek whose responsa remain among the most important ever written. He died in 1408.

Did the Rivash convert? There were a number of rabbis, admittedly not of the Rivash’s level, who converted to Christianity in Spain, so the idea is not impossible. We also have to remember that the conversion of the Rivash, if it indeed occurred, was also only a temporary event. I do not think it casts aspersions on a great rabbi if we find that when faced with the terrible choice, he did not choose martyrdom. Everyone realizes that this is never an easy choice. This was especially the case in Spain which, unlike Germany, never had a culture extolling Jewish martyrdom (and we know that large numbers of Spanish Jews chose conversion over death).

In analyzing this matter, the real issue that experts should focus on is how reliable are the government documents. R. David Bar Sheshet is a descendant of the Rivash and recently published a biography of his illustrious forefather. Some might be surprised that in an “Orthodox” biography he deals with the matter of the supposed conversion. However, being that this is by now a well-known “fact,” it is basically impossible to ignore. Not surprisingly, Bar Sheshet argues against the claim that the Rivash converted.[31] Yet this is not simply a hagiographic perspective, and I myself am not convinced. If indeed the Rivash converted, the Church would presumably have used this as a propaganda tool, yet we have no evidence that this was ever done. Furthermore, does it make sense that no Jewish sources of the time mention the apostasy of such a prominent rabbi?[32]

Among my hobbies are visiting the graves of great Torah sages, and this hobby has taken me around the world. What about visiting the graves of the Rivash, and also R. Simeon ben Zemah Duran, the Tashbetz, both of whom are buried in Algiers?[33] Recently, I was in a Paris airport waiting for my flight to Tunisia. At very next gate was a flight to Algiers. Yet despite how easy it would be to travel there, I have yet to go. There is no Jewish community in the city and I don’t know how safe it is to visit Jewish sites. One day when I am convinced it is safe, I will travel there, much like I will travel to Baghdad to visit the grave of the Ben Ish Hai.

Fortunately, one person did make the trek to Algiers. He has put online pictures of the cemetery where the Rivash and R. Simeon ben Zemah Duran are buried, having been moved there from the original cemetery at the end of the nineteenth century. Even before the move they had been given new tombstones.[34] See his website here.

This is the Rivash’s grave. The picture is taken from the just mentioned website.

This is R. Duran’s grave. The picture comes from the same website.

Excursus

Due to the censor, or perhaps even self-censorship, in certain European prayer books negative expressions directed against idolatry, and hence bearing a possible anti-Christian interpretation, were turned into anti-Islamic expressions. See Leopold Zunz, Die Ritus des synagogalen Gottesdienstes (Berlin, 1919), p. 222. Halakhic works were also affected. See, for example, R. Abraham Danzig, Hokhmat Adam 153:1, where some printings have:

ואם שרוי הוא בין ישמעאלים

Every reader should easily grasp that in this passage ישמעאלים does not really mean Muslims.

Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Avodah Zarah 9:4 reads:

הנוצרים עובדי עבודה זרה הן ויום ראשון יום אידם הוא. לפיכך אסור לשאת ולתת עמהן בארץ ישראל יום חמישי ויום ששי שבכל שבת ושבת. ואין צריך לומר יום ראשון עצמו שהוא אסור בכל מקום

In the textual notes in the Frankel Mishneh Torah, they cite a manuscript that reads:

ישמעלים [!] עובדי ע”ז הן ויום ששי יום אידם . . . ואין צריך לומר יום ששי עצמו

In the Shabbat morning Amidah, we read:

וגם במנוחתו לא ישכנו ערלים

Steinschneider noted that some texts replace arelim with “Ishmaelites.” See Polemische und Apologetische Literatur in arabischer Sprache zwischen Muslimen, Christen und Juden (Leipzig, 1877), p. 374. This change of text was done in Christian countries for obvious reasons and should fool no one. Thus, it is surprising that Salo W. Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, vol. 6, p. 327 n. 15, writes as follows about the version that contains “Ishmaelites”:

This was hardly an invention of later generations of Jews who, living in Christian countries, sought to avoid difficulties with censors. . . . If Maimonides, in his formulation, substitutes arelim (uncircumcised) for “Ishmaelites” (cf. M.T. Seder Tefillot at the end of the second book; here switched to the Musaf prayer), this was merely in line with his general preference for Islam as against Christianity.

This is complete nonsense. Maimonides did not substitute arelim for “Ishmaelites.” The text he had, which is the authentic text of the prayer, included the word arelim.

Here is a responsum of R. Eliezer Isaac Fried, from Hut ha-Meshulash, no. 28. This responsum is cited in many of the discussions dealing Islam and halakhah, in particular with reference to mosques. In my article on the topic from many years ago I too cited this source. See “Islam and the Halakhah,” Judaism 42 (Summer 1993), p. 337.

I recently had occasion to look at this responsum again, and I see that everyone has misunderstood it. It is obvious that R. Fried is not really speaking about building a mosque but a church. When, in the responsum, he speaks of placing the crescent in the mosque, this is really code for crucifix. In fact, the entire responsum assumes that he is speaking about a religion of avodah zarah, which is the obvious sign that he is really speaking about Christianity.

My excuse for misreading the responsum years ago is that I was young and unsophisticated. However, it is very surprising to me that many great talmidei hakhamim have also cited this responsum without realizing that it is not really referring to Islam. See also here where I discuss a mistake by R. Judah Aszod who assumed that in a particular responsum the Hatam Sofer was discussing candle lighting as part of a religious celebration in India, when it is obvious that the Hatam Sofer is really referring to the practice of European Christians.

For an example of self-censorship in the opposite direction, namely, the removal of references to Islam, see this page of a responsum of R. Rahamim Joseph Franco, Sha’arei Rahamim (Jerusalem, 1881), vol. 1, Orah Hayyim, no. 5, p. 8b (look at the paragraph beginning ושוב).

2. I would like to mention some more mistakes I have found in the ArtScroll siddur and machzor. I believe that it is worthwhile to call attention to such mistakes, not only for their own sake, but because ArtScroll has made corrections in the past when these types of errors have been pointed out, and they no doubt will continue to do so in the future.

I myself have noticed a number of corrections that ArtScroll has made, and it could be that the example I will now discuss is an additional one, but I have not personally seen the correction. In response to an earlier post, R. Elazar Meir Teitz informed me that in the prayer recited before taking the Torah out of the Ark on Shabbat morning, in the words היטיבה ברצונך את ציון, ArtScroll mistakenly puts the accent in ברצונך on the penultimate syllable (and when we sing these words with the popular tune the accent is indeed on the penultimate syllable). I checked my ArtScroll siddurim and machzorim and that is indeed where the accent is. However, I have been told that in the new printings of at least one of the various ArtScroll siddurim (but not of the machzorim) this has been corrected and the accent is now on the final syllable. Can any reader confirm that this is indeed the case?

I noticed over Yom Kippur that ArtScroll has a very strange translation in the על חטא prayer. We say:

ועל חטא שחטאנו לפניך ביודעים ובלא יודעים

ArtScroll translates this: “And for the sin that we have sinned before You against those who know and against those who do not know.” I am certain that this is a mistake, and that ביודעים ובלא יודעים means, “with knowledge or without knowledge,” in other words, “wittingly or unwittingly.” I assume ArtScroll was driven to its translation because earlier in the prayer we say בזדון ובשגגה. Thus, if ביודעים ובלא יודעים means “wittingly or unwittingly,” then it is repeating what was earlier said. Furthermore, we also say earlier בבלי דעת and בדעת ובמרמה, so this would seem to be more of the same. Yet I do not think that a prayer with repetitions creates difficulties, and in this case, I think it makes more sense than translating the passage the way ArtScroll does. I am curious to see if readers agree with me.[35]

The final mistake I would like to call attention to is one that is found in most siddurim and collections of zemirot, so ArtScroll is in good company. It is noteworthy that the Koren siddur and the new RCA siddur get it right. The old RCA-De Sola Pool siddur also got it right.

In the Sbbath song ברוך א-ל עליון, it states:

ואשרי כל חוכה

מאת כל סוכה שוכן בערפל

The meaning, as translated by ArtScroll, is:

Praiseworthy is everyone who awaits a double reward

From the One Who sees all but dwells in dense darkness.

Here is how the Hebrew page appears in the ArtScroll Zemiroth,[36] p. 186.

The problem here is that if you look at the Hebrew you can see that the English has not been translated properly. כל-סוכה does not mean “the One Who sees”, but “everyone who sees.” The word כל has a kamatz which means that it is connected to the following word. In the Zemiroth, ArtScroll puts the makef in, just like almost always in the Masoretic text of Tanakh כל with a kamatz has a makef.[37] But the meaning of the passage is the same even without the makef, and in the siddur ArtScroll does not include it.

In order for the passage to mean “the One Who sees all,” the word כל must have a holam.[38] This point is actually made by R. Nota Greenblatt, who states that the version found in ArtScroll and many others, where the word כל has a kamatz, is nothing less than heresy since God has been replaced by humans.

3. I want to call readers’ attention to an important volume that has just appeared. Seforim Blog contributor R. Moshe Maimon has published the first volume of his edition of R. Abraham Maimonides’ commentary on Genesis. Maimon’s improvements on the earlier translation from the Arabic make the work a pleasure to read. His explanatory notes are simply fantastic, taking into account all relevant sources, both traditional and academic, that can illuminate the text. This will now become the standard edition of R. Abraham’s commentary, and I can think of no greater honor for Maimon than this. Hopefully, this publication will lead to a surge of interest in the commentary of R. Abraham, much like R. Kafih’s new translation of Maimonides’ Commentary on the Mishnah did for this work. The book is available at Biegeleisen, and can also be purchased online at Mizrahi books here.

[1] See Isaiah Sonne, “Avnei Binyan le-Korot ha-Yehudim be-Italyah,” Horev 6 (1941), pp. 100ff.; Elisheva Carlebach, The Pursuit of Heresy: Rabbi Moses Hagiz and the Sabbatian Controversies (New York, 1990), pp. 237ff.

[2] This is noted by Carlebach, The Pursuit of Heresy, p. 331 n. 18.

[3] See Excursus

[4] Peninei Shadal (Przemysl, 1888), p. 12. See the recent discussion of Nehemiah by Yaakov Spiegel in Hitzei Giborim 11 (2019), pp. 1146ff. Spiegel mentions that Torah writings from Nehemiah remain in manuscript. He also notes that in a recent printing of Basilea, Emunat Hakhamim, Nehemiah’s haskamah was removed (and perhaps surprisingly, the printer acknowledged that it was removed).

[5] Cecil Roth, Studies in Books and Booklore (Farnborough, England, 1972), p. 44 (Hebrew section).

[6] See Alexander’s appendix to John Hatchard, The Predictions and Promises of God Respecting Israel (London, 1825), p. 38. See also Kelvin Crombie, A Jewish Bishop in Jerusalem (Jerusalem, 2006), p. 13, and the entry on him in the Dictionary of National Biography, here.

[7] R. Joseph Tanugi, Toldot Hakhmei Tunis (Bnei Brak, 1988), pp. 233-234; R. Abraham Khalfon, Ma’aseh Tzadikim (Jerusalem, n.d.), p. 309.

[8] L’Univers Israelite, Oct. 7, 1932, available here; André N. Chouraqui, Between East and West: A History of the Jews of North Africa, trans. Michael M. Bernet (Philadelphia, 1968), p. 72.

[9] See Victor A. Mirelman, Jewish Buenos Aires, 1890-1930 (Detroit, 1990), p. 89.

[10] “Ha-Rav Moshe Soloveichik u-Ma’avakav be-‘Moetzet Gedolei ha-Torah’ ve-‘Agudat ha-Rabbanim’ be-Polin,” Hakirah 25 (2018), p. 47.

[11] I thank Menachem Butler for sending me this image.

[12] See Yehoshua Mondshine, Ha-Tzofeh le-Doro (Jerusalem, 1987), p. 37.

[13] Entzyklopedia le-Hakhmei Galizia, vol. 5, col. 154.

[14] Ha-Darom (Tishrei 5723) 16 p. 150.

[15] Another rabbi who met an unfortunate demise was R. Isaiah ha-Levi, author of the first Ba’er Heitev on the Shulhan Arukh (not Ba’er Heitev found in the standard editions). R. Meir Eisenstadt, Meorei Esh, beginning of parashat Shemini, tells us that on his way to Eretz Yisrael, R. Isaiah, his wife, and daughter were killed in a fire in their hotel. Regarding the different commentaries with the name Ba’er Heitev, see R. Yehiel Dov Weller in Yeshurun 17 (2006), pp. 825ff.

In the old translation of Maimonides’ commentary to Mikvaot 4:4, he writes about a certain rabbi: ונהרג על זה באמה ובזרוע. This led to all sorts of speculations about which rabbi was killed. However, this is a mistaken translation. See R. Kafih’s note in his new translation, and also his commentary to Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Mikvaot, vol. 2, p. 461. In a future post, I will mention a few rabbis who were killed by Jews, as well as cases of attempted murder. For now, I merely want to call readers’ attention to Prof. Shnayer Leiman’s email published in Chaim Dalfin’s new book, Torah Vodaas and Lubavitch (Brooklyn, 2019), p. 203.

There was a rabbi who allegedly was killed by mobsters. I heard from reliable sources that he was beaten, rolled in the snow and left to die. (Perhaps the goal was to frighten him, not kill him.) He survived the ordeal, but died shortly thereafter from pneumonia. The rabbi was Rabbi Yaakov Eskolsky, famous author and Rabbi of the Bialystocker Shul on the Lower East Side. I’m not aware of any written account that mentions this.

Leiman also mentions that Rabbi Israel Tabak, the son-in-law of R. Eskolsky, in discussing his father-in-law’s death mentions nothing about any foul play. See Tabak, Three Worlds (Jerusalem, 1988), p. 156.

R. Eskolsky served as a rabbi in Scranton for a few years. See his biography here. I previously wrote a bit about him here. In Tabak’s book, p. 152, it mentions that R. Eskolsky celebrated Thanksgiving, and that at a Thanksgiving dinner Tabak attended, he “emphasized the significance of Thanksgiving Day for our people who came to the United States from Eastern Europe, and especially from Russia. Coming to America, the land of freedom and opportunity, was like emerging from darkness into light and certainly deserved to be marked by thanksgiving, both to G-d and to America that treated its citizens so well.” I believe that for any non-hasidic rabbi in America in the early part of the twentieth century, the notion that there was something religiously problematic with celebrating Thanksgiving would have been incomprehensible.

Shimon Steinmetz sent me this picture from the Forverts, Oct. 23, 1930. I find it fascinating that R. Eskolsky served as a justice on the “Jewish Arbitration Court.”

[16] See Yehoshua Mondshine, “Aminutan shel Iggerot ha-Hasidim me-Eretz Yisrael,” in Katedra 64 (1992), p. 89 n. 152.

[17] “Perfeyt Duran be-Italyah ve-Goral ha-Sefarim ha-Ivriyim Aharei Meoraot 1391,” Ba-Derekh el ha-Modernah: Shai le-Yosef Kaplan (Jerusalem, 2019), pp. 61-91.

[18] The Secret Faith of Maestre Honoratus (Philadelphia, 2015), pp. 20, 28.

[19] See Kozody’s suggestions to explain this, Secret Faith, pp. 30ff. Regarding when his polemical works were written, see Benzion Netanyahu, The Marranos of Spain (Ithaca, 1999), pp. 221ff.

[20] Twersky discusses this text in “Religion and Law” in S.D. Goitein, ed., Religion in a Religious Age (New York, 1974), pp. 69-82. Regarding Twersky, I recently discovered this video of one of Chaim Grade’s lectures at Harvard from October 1981, and Twersky introduces him at the beginning. Unfortunately, only the first part of the lecture appears in the video. If anyone knows if the second part exists, please let me know. Menachem Butler was kind enough to send this page from the Boston Jewish Advocate, Oct. 22, 1981, announcing the Grade lectures.

Grade had earlier lectured at Harvard in 1977. Regarding these lectures, see Allan Nadler’s recollections here.

[21] Here is the first page of an article by Yehudah Hershkowitz that appeared in Yeshurun 9 (2001), p. 572.

Note how Duran is referred to as “Rabbenu”. The author is aware that Duran apostatized, but he, like everyone before him, assumed that Duran later returned to Judaism.

[22] Regarding martyrdom, R. Moshe Feinstein makes an interesting point in Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Deah III, no. 108 (p. 353). We all know that a convert must accept the mitzvot for the conversion to be valid. What about if a convert honestly states that while he accepts the mitzvot, if confronted with violating a prohibition for which martyrdom is required, he knows that he will not have the courage to be martyred? Is this to be regarded as rejecting a commandment which means that he cannot be converted? R. Moshe says no, as acceptance of the mitzvot means that you intend to fulfill them under normal circumstances, and extreme cases such as those that involve martyrdom do not impact this acceptance.

[23] For R. Elijah Capsali’s report of the forced conversion, by actual physical force, see Abraham Gross, Struggling with Tradition (Leiden, 2004), p. 81. See also the Christian report in E. H. Lindo, The History of the Jews of Spain and Portugal (New York, 1970), p. 330. Another forced convert in Portugal who later became famous was R. Solomon Ibn Verga, author of Shevet Yehudah. R. Joseph Garson, who later escaped to Salonika, also appears to have undergone forced conversion in Portugal. See Joseph Hacker, “Li-Demutam ha-Ruhanit shel Yehudei Sefarad be-Sof ha-Meah ha-Hamesh Esreh,” Sefunot 2, new series (1983), pp. 29ff. As with R. Levi, we do not know the circumstances of the forced conversions of R. Ibn Verga and R. Garson. Since it appears that R. Jacob Ibn Habib was also in Portugal in 1497, then presumably he too was converted, either “willingly” or not. See, however, Marjorie Lehman, The En Yaaqov: Jacob ibn Habib’s Search for Faith in the Talmudic Corpus (Detroit, 2012), pp. 26-27. Regarding whether R. Isaac Karo was in Portugal then, or if he succeeded in leaving prior to the mass conversion, see Karo, Derashot R. Yitzhak Karo, ed. Shaul Regev (Ramat-Gan, 1995), pp. 9-10.

[24] Kuntres ha-Semikhah, in Teshuvot R. Levi Ibn Habib, no. 147, section 4 (p. 39 in the new edition).

[25] Ibid., no. 148 section 5, p. 52.

[26] R. Solomon ben Adret, She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rashba, vol. 6, no. 179, explains that this is because a person’s intellect is not sufficiently developed until age 20.

[27] R. Moses Sofer rejects the notion that one is not punished by Heaven for sins committed before age 20. See She’elot u-Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 155. For more on this matter, see R. Pinchas Zabihi, Ateret Paz, vol. 3, no. 1, and here.

[28] Teshuvot R. Levi Ibn Habib, no. 148, section 5 (p. 53 in the new edition).

[29] Divine Law in Human Hands (Jerusalem, 1998), p. 170.

[30] Riera, “Le-Toldot ha-Rivash bi-Gezerot 1391,” Sefunot 17 (1983), pp. 11-20.

[31] Rabbi Yitzhak Bar Sheshet (Beitar Ilit, 2017), pp. 83ff.

[32] In this post, I have not dealt with accusations of rabbis’ apostatizing that arose in the contexts of disputes. For an example where hasidim accused one of their mitnagedic opponents, R. Leib Rakowski of Plock, of apostasy and also of marrying a non-Jewish woman, see Marcin Wodzinski, Studying Hasidism (New Brunswick, N.J., 2019), p. 120. This occurred after they tried to beat up the rabbi. See ibid., p. 119.

[33] In rabbinic literature Algiers is written as ארג’יל. This is due to the influence of the Spanish exiles who settled in North Africa, as in Spanish Algiers is pronounced as Argel. I was surprised to see that a generally careful scholar, Tuvia Preschel, Ma’amrei Tuvyah, vol. 1, p. 58, recorded the following false information.

הם [יהודי אלג’יר] לא רצו לכתוב אלגיר שהיא מלשון אלה וגם “גירא בעיניך השטן” וע”כ הסבו שם העיר לארג’יל, לשון אור וגיל וסימנה טוב

[34] Regarding the transfer of the remains, see Bar Sheshet, Rabbi Yitzhak Bar Sheshet, pp. 83ff.

[35] In his Derashot Kol Ben Levi, p. 130, R. Jehiel Michel Epstein’s explains ביודעים ובלא יודעים as follows:

היודעים המה העבירות שאין להם מבא בהיתר כלל והלא יודעים הם המותרות מההיתר שאין האדם מרגיש בנפשו כלל שזהו חטא וא”כ אין ידוע כלל שחטאנו לפניך

For a homiletic explanation that is found in many different sources, see R. Zvi Hirsch Ferber, Siah Tzvi, p. 162:

וזה שאנו מתודים על חטא שח”ל ביודעים, זה שהגיע להוראה ואינו מורה, ובלא יודעים, שלא הגיע להוראה ומורה

Yisrael Meir Lau,Yahel Yisrael: Avot, ch. 4, p. 246, writes:

בלא יודעים – הכוונה לחטא שחטאנו, מחמת שהיינו במצב של “לא יודעים”, שבאשמתנו לא ידענו את הדין, ועברנו על העבירה בלא לדעת כלל שיש בכך איסור. חומרתו של מעשה הנעשה “בלא יודעים” היא, ממש כמעשה הנעשה “ביודעים”, ועל שניהם כאחד אנו מתוודים ומבקשים שהקב”ה יסלח לנו ביום הכיפורים

[36] My copy was published in 1979. Later, ArtScroll changed the transliteration to Zemiros.

[37] כל with kamatz is pronounced as kamatz katan. The only exceptions in Tanakh are Psalms 35:10: כל עצמתי, and Proverbs 19:7: כל אחי-רש. In these cases there is no makef after כל and therefore it is pronounced as kamatz gadol.

Isaiah 40:12 is another biblical verse with the word כל without a makef and it too has a kamatz gadol:

וכל בשלש עפר הארץ

Yet the word כל here is completely different than all other appearances of כל in Tanakh. This passage means, “and comprehended the dust of the earth in a shalish-measure.” The word כל we are all familiar with is from the root כלל. The word כל in Isaiah 40:12 is from the root כול.

[38] I found another mistake in ArtScroll’s version of the song, and again, many others, including Koren and the new RCA siddur, make the same mistake. Yet the RCA-De Sola Pool siddur gets it right, as does Birnbaum. In the first stanza it reads עד אנא תוגיון. ArtScroll vocalizes the last word as “tugyon” (shuruk, holam) Yet this is a verse in Job 19:2 and the correct pronunciation is “togyun” (holam, shuruk).

The fifth stanza ends רוחו בם נחה. ArtScroll puts the accent in נחה on the penultimate syllable. However, in the context of the song, where all the other stanzas have the parallel rhyming word with the accent on the last syllable, I don’t think there is any doubt that נחה should also be read with the accent on the last syllable, despite what the grammatical rule may say.

55 thoughts on “Apostates and More, Part 2”

B”H.

Wow, wow. Thank you once again, for your wonderful posts.

Thanks to you, we get to read high-quality serious works, without needing to resort to a paywall or ask access of Jstore or Project Muse, we don’t need to look around on Academia or follow a private personal Blog. Rather we get full access in an open public forum for all to see. This is really great.

Just two small comments.

1. I am sure that in your article on Rabbi’s who were murdered that maybe we will get insight to the Rabbi mentioned here.

http://judaicaused.blogspot.com/2018/12/2-titles-published-by-rebbetzins-after.html

2. As a tangential point. With all the fights that the Hakirah articles Document with Reb Moshe Soloveitchik and the Agudah, including RCO, how should one understand the Hesped (and what it implied) that Rav Soloveitchik said on RCO?

Thanks so much for your kind comment.

Your second point is something that I have thought about. Knowing how his father did not get along with RCO or with Agudat Yisrael for that matter, what does it mean that the Rav not only gave that hesped but also joined the Agudah? I don’t have an answer to this. (The Agudah you refer to is the Agudat ha-Rabbanim in Poland)

“(The Agudah you refer to is the Agudat ha-Rabbanim in Poland)”

Rav Moshe had issues with both Agudat HaRabbanim in Poland, as well as Agudat Yisrael. Fuss documented the issues with both.

As far as the Rav joining Agudat Yisrael in America, and giving the hesped for Rav Chaim Ozer (in his father’s lifetime no less), I don’t think these are problematic. For one, the Rav had a personal relationship with Rav Chaim Ozer (his mother-in-law and Rav Chaim Ozer were cousins), and the Rav spent time with Rav Chaim Ozer in Vilna (his wife’s hometown. Was Rav Chaim Ozer his mesader kiddushin, anyone know?) I recall Rav Meir Lichtenstein saying that he once heard the Rav say how frustrating it was to talk in learning with Rav Chaim Ozer, because whatever chiddush the Rav would tell him, Rav Chaim Ozer would pull out some obscure sefer and show him that exact chiddush. The Rav certainly had tremendous respect for Rav Chaim Ozer, having known him personally.

Rav Moshe disagreed with Rav Chaim Ozer regarding Rav Chaim’s position on Agudat Yisrael, and there is no evidence that the scope of the machloket extended beyond that. I have no doubt that he respected Rav Chaim Ozer as a gadol b’Yisrael.

As far as joining Agudat Yisrael in America, Agudat Yisrael in America was an entirely different type of organization than in Europe, and with different goals, because the landscape in America was so different than in Europe. In R’ Shlomo Pick’s article on the Rav’s biography in one of the BDD volumes he points out that Rav Moshe himself was on certain Agudat Yisrael committees in 1940.

BH

Thank you very much.

Concerning rabbis who were killed, here is another one.

https://www.nytimes.com/1989/03/20/nyregion/police-find-body-of-rabbi-floating-in-bay-off-brooklyn.html

He was killed by the Mafia after failing to repay loans he took out to build his shul.

If I remember well, you will find out more about this last one here : https://rabbidunner.com/grand-rabbi-or-grand-larceny/

Re: footnote #15

re: “non-hasidic rabbi in America in the early part of the twentieth century” – Rabbi Eskolsky was actually born into a family of Slonimer chassidim in Mir. His main learning was at Litvishe/non-chassidic yeshivos (Mir, Slonim, Kovno Kollel) but during his many years at Slonim he had much direct contact with the Divrei Shmuel (2nd Slonimer rebbe) who was not directly affiliated with the yeshiva. Prior to his arrival in the USA in 1906, he served as Rav/Av beis din for a few years in two different shtetlach with high concentrations of Stoliner chassidim.

re: Forverts picture – The picture with the Jewish Arbitration Court did appear in the Forverts on an October 23 but it was actually 18 years later – Oct. 23, 1930 – within four months of the time Rav Eskolsky passed away – see here for a direct link to page 12 of that day’s issue: http://jpress.nli.org.il/olive/apa/nli/?href=FRW%2F1930%2F10%2F23&page=12

re: “there was a rabbi who was allegedly killed by mobsters….”

A sampling of news reports from the time of Rav Eskolsky’s petira indicate that he died at his home, early Tuesday morning Feb. 17, 1931, from influenza after an illness of several weeks. (see Morgen Journal February 18, 1931, p.1; New York Times, February 17, 1931, p.25; New York Evening Post February 17, 1931; Detroit Jewish Chronicle (weekly) February 20, 1931, p.2)

I first heard the rumor of foul play over thirty years ago. Apparently, it was a well-known rumor among Lower East Siders that I have since heard from some others. Within a few years of first hearing the rumor, I asked my father a”h about it. He told me that he heard such a rumor from his own father (my grandfather, Ben Eskolsky (later Escott) – oldest child of Rabbi Eskolsky) who heard the rumor at some point. My father didn’t indicate whether my zayde believed the rumor to be true.

I saw Prof. Leiman’s quote re: foul-play (thank you Marc for sending this to me at an earlier date) and reached out to him for further details – the following was in his response to me re: the source of this story “…he is a reliable source, as I indicated, but like me, not an eyewitness. So, at best, his testimony is labelled עד מפי עד, i.e. hearsay. He is elderly, and not well, and I’m not sure he can communicate with anyone….”

Aside from Rabbi Dalfin’s recent book, I have seen a small number of brief references to the rumor in print. The earliest occurrence seemingly appears in רבי מאיר בר-אילן מוולוזין עד ירושלים חלק ב’ עמ’ 559 published around 1940 which in a brief section discussing Rav Eskolsky hints to the rumor by mentioning:

“…בנפלו בידי בני עוולה…” (when he fell [at the time of his death] in the hands of evil-doers)

Rav Berlin had been friendly with Rav Eskolsky during his years in New York, and was a colleague in efforts for Mizrachi and for Ezras Torah.

Almost 10 years ago, someone mentioned to me that while learning in a certain New York yeshiva in the late 1960s, his rebbe mentioned the following experience: in the early 1930s, the “syndicate” coerced him into helping them obtain Prohibition-era alcohol under the guise of religious use. Shortly afterwards, Prohibition was repealed and that episode fortunately ended. They coerced him by threatening him with the same fate as R. Yaakov Eskolsky whom they had approached with the same deal but R. Eskolsky wouldn’t play along. They took R. Eskolsky to the Hunts Point section of the Bronx in the winter and disrobed him and left him out in the cold where he was found (frozen? dead?) a few days later.

All that being said, I have a very strong sense that the foul-play rumor was unfounded. I do believe the above account that the rabbi (in later years a yeshiva rebbe) was actually threatened by the mob. I also believe that this was a likely original source for the foul-play rumor. However, I believe that the mobsters took advantage of the recent death of R. Eskolsky (who died in his mid 50s) by lying to that rabbi as a means of extortion so that they could achieve a source of illegal business.

This is mainly based on 1) a brief discussion my older brother and I had with our great-uncle Dr. Harry Goldin in July 1995. 2) an interview with Dr. Goldin conducted by my father’s cousin, Yacov Tabak a”h (son of the aforementioned Rabbi Israel Tabak) on chol hamoed Sukkos 1997. Dr. Goldin was married to Anna (Eskolsky) Goldin, third child of R. Eskolsky.

My “Uncle Harry” used words such as “בלבול” and “שקר וכזב” while dismissing the foul-play rumor as nonsense. He was the personal physician of his father in law and spent significant time with R. Eskolsky in the days leading up to his passing. There were typical winter colds going around and the rav just developed a regular viral infection which eventually got worse. He passed away at home on the morning of Tue. Feb. 17, 1931 and Dr. Goldin had given him a checkup on the previous Thursday or Friday. He said that Rav Eskolsky had an infection (in the lungs). He had seen no marks on the rav’s body that indicated foul play and that he was not found outdoors prior to the illness. The rav had been keeping a regular schedule the week before and asked if he could go to shul as usual on Shabbos. Dr. Goldin prescribed some medication and told him to stay at home. Over the weekend, R. Eskolsky went into congestive heart failure as a result of his high blood pressure. A person with a cardiac issue who develops an infection is always in danger. Dr. Goldin lamented his own medical knowledge of back in the 1930s and said that with modern medical treatment, Rav Eskolsky could have lived for many more years – that “Today – a person goes into congestive heart failure – there is treatment.…… as soon as you go into heart failure, within twelve minutes the person is all right”.

Dr. Goldin thought that the foul-play rumor was spread by someone who had malicious intent toward R. Eskolsky (one could ask what type of defamation would be caused by saying someone was the victim of a crime, but maybe it was just something that sounded bad…) . Based on the account I heard re: the rav who was threatened by the mob to procure illegal alcohol, I imagine the rumor had a factual basis (as the rav believed the mobsters) and that the rumor was spread with no malice.

It should also be noted that Rabbi Tabak and Lillian (Eskolsky) Tabak, (4th child in Rav Eskolsky’s family) were engaged well before R. Eskolsky passed away. R. Tabak was then a young rav in the NYC area (Union City, NJ) and was already considered part of the family. Lillian was living at home. In addition to Rabbi Tabak’s account in Three Worlds (1988) he had a slightly more expanded version of his account in a speech delivered in Baltimore in honor of his father in law in 1975 “…..I visited the rav a few days after he came down with his last attack. He did not look so bad, but I could see that he suffered pain in his side. No one dreamt that the end was near. It came like a bolt from the blue……”. This indicates R. Tabak visited R. Eskolsky at home not long before he passed away and that he was already sick but his death was totally unexpected.

It could be telling that their own son Yacov, never heard of the foul-play rumor until the early 1990s and never heard it from either of his parents. Rabbi Mitchel Eskolsky was R. Yaakov’s 2nd child. He was a rav in Baltimore in early 1931 before succeeding his father at the Bialystoker shul (when this happened, R. Tabak succeeded his new brother in law in the Baltimore position). I recently spoke with one of his daughters who said she never heard of the rumor from her father and only heard of it after R. Mitchel passed away.

In the end, I’m not convinced 100%, but I give much more credence to Dr. Goldin’s account than the account of the mobsters who were likely using their story as a mere threat. If the foul-play story had been true, one could imagine angry family members seeking justice if a crime had actually occurred. Even if it could be argued that this would be counter-balanced by fear of mob repercussions, Dr. Goldin would have not had such a fear 65 years after the fact.

For all of the possibilities, one must be mindful that the ones who would have known what actually happened were Rav Eskolsky and/or close family members who witnessed him in his final days/weeks, and/or the alleged perpetrators of any foul play. To support the latter, reports by police, a hospital or a morgue would provide more solid evidence but it would be very challenging at this point to find archives that would house that information if it still exists at all.

Hopefully at some point I’ll have a chance to give this topic a fuller treatment as there are more details. Years ago, one of my brothers and I planned to publish an expanded reprint of Rav Eskolsky’s Sefer Taryag Mitzvos with a biographical section, but that has yet to come to fruition.

For further information on Rabbi Eskolsky, see https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/יעקב_איסקולסקי

Moshe Escott (great-grandson of Rav Yaakov Eskolsky zt”l)

Regarding the point in your final footnote that תוגיון should be pronounced togyun as in the passuk and not tugyon; is it not possible that this is merely poetic license to rhyme with elyon, fidyon, and tziyon?

Avraham,

In looking over it again, I have to now say that I I agree with you. I didn’t originally because it is a biblical verse, I was focusing on the last words that rhyme, and I saw other siddurim that didn’t vocalize this way (including one which is really exacting). Also, if you look at a number of the other verses there is rhyming in words in the first three sections but not the last section, so I assumed that the first verse also followed this pattern. But now that I examine it again, I am inclined to agree with you. Of course, this is really not an issue of Artscroll vs. Birnbaum. The vocalization of Artscroll goes back to older siddurim and they just went along with what they found.

Your point is particularly valid as I myself made the point about the accent not having to follow grammatical rules in rhyming. In a future post I will raise this matter and say that I agree with you (even though Birnbaum, De Sola Pool and others will be upset . . .) So thanks for pointing this out

Also, Togyun nafshi in the pasuk is a verb, “you will agonize my soul”, addressed to those who are doing so; whereas in the piyut it’s a noun, “how long is the agony, the sighing soul”. Therefore it makes sense to change the nikud. As Rashi says, it’s related to the noun Tugah (or should that be Togah?)

Artscroll’s translation of ביודעין ובלא יודעין is odd. For one, the phrases ביודעין and בלא יודעין are not uncommonly used to describe doing something with or without intent/knowledge. (Of course it’s impossible to say that the expression isn’t due to a ‘mistranslation’ of the language of the vidui, but that seems unlikely.) Additionally, translating it like Artscroll creates an awkward sentence that reads, “the sins we sinned against you, against people who knew or didn’t know of our acts”, which reads very awkwardly and not at all smoothly like the style of the other lines in the vidui. It also expresses a different idea from all of the other examples, which all describe the sinner’s behavior and mindset, or in a few cases the act of sin, but in none the details of the sin itself or it’s effect.

I’ve always naturally read the meaning your way, and I think that’s how most people naturally read it. Truthfully, I think it’s so obvious, that for Artscroll to change it they must have done it intentionally, ביודעים, for some specific reason or on someone’s advice. For example, perhaps there’s a pirush or halachic source that says an aveira without knowledge (as opposed to beshogeg) is not an aveira and requires no vidui or kapara, or a similar idea, based on which someone at Artscroll may have felt the need to reinterpret the language.

“it’s effect”

should be “its”. “it” does not take a possessive apostrophe.

Is there any way of telling how many, if any, of these “he did it for a shiksa (or random Jewish woman)” stories are true? They sound like easy excuses.

I once read an article that referred to a prominent German university, which granted the PhDs of some well-known Jewish personalities in the era of which you speak, as “a notorious diploma mill.” Was the ease of getting the degree specific to some places only or a general issue?

All German universities had easy PhDs. My sense is that University of Berlin dissertations are a little more significant than the others, but also not significant pieces of work.

PhD’s in Germany were the equivalent —if that!— of today’s MA. It was more a social title, you could write “Dr” before your name. To teach in a university you had to write a second, “ habilitation” thesis, which was the “real” doctoral thesis.

I would offer that the Hebrew word כל’s root is not כול. There are a number of words in the mishqal of אור and קול (e.g. עור, טוב, etc.) that always appear “full,” written with the waw, because the waw is part of the root, and in their plural and construct forms, the full holam remains, whereas there is a second mishqal which includes כֹל, דֹב, and רֹב, and other words that always appear “deficient,” without the waw, and in both plurals and constructs, the holam is downgraded to either qubbutz or qamatz qatan and a dagesh is added to the second letter to mark the missing other letter of the root. In the case of כל, the possessed form, for example, is כֻּלּוֹ. I would argue that in this case, the root of this word is כלל. With regards to רב, which has forms similar to כל, it is clear that the root is רבה, as its hif’il infinitive is להרבות. As pointed out in the Daat Mikra, the fact that sometimes the construct form of כל is accented indicates the ashkenazic tradition that qamatz has a distinct sound unto itself, and the sephardic idea of dividing all qamatzim among two vowels that sound very different from each other but suspiciously like two other vowels is a retcon.

I don’t disagree. Look again at what I wrote.

“The word כל we are all familiar with is from the root כלל. The word כל in Isaiah 40:12 is from the root כול.”

Oops, I wrote the end of that quickly, without paying attention to what I was saying; גבעות, are not valleys of course, but heights, or hills, but the gist of what I was saying holds.

I can’t retract my comment… or correct it. So, sorry. Although I believe that sephardim, israelis, or others who only have two vowel sounds for the entire spectrum of sounds between patah and holam should not pronounce the word כל as it appears in those two verses as what they believe is a qamatz gadol, but instead should learn how to pronounce a sound that is distinctly qamatz and use it.

Great post as usual.

“I still haven’t got rid of…”

Think it should be: “haven’t gotten”.

Correct

“R. Levi also mentions that he was not yet a bar onshin when he converted. The evidence we have shows that he was older than 13 in 1497, so when he says that he was not yet a bar onshin, it must mean that he was under the age of 20.”

This is definitely what he means – that’s why he writes “בבית דינו”, i.e. בבית דין של מעלה.

The comment on כל-סוכה doesn’t make sense. What does it mean to ‘wait for a double reward from all those who see’? People don’t reward, הקב”ה rewards.

In addition there is no difference in meaning whether כל is connected to the next word or not, the only difference is whether it should be treated or read as one word or two. True that both סידור עבודת ישראל and Heberman in ידיעות המכון לחקר שירת העברית have a חולם but that may be because of the meter (which admittedly I don’t know much about).

You wrote:

“The comment on כל-סוכה doesn’t make sense. What does it mean to ‘wait for a double reward from all those who see’? People don’t reward, הקב”ה rewards.” Exactly. That is why no one translates it as “from all those who see” and there is no hyphen between כל סוכה. That is the entire point. I think you read it too quickly and didn’t catch this.

Your second paragraph is completely incorrect in the context of the passage we are examining. The entire meaning of the passage depends on the word having a holam.

Marc: With all respect, while your criticism of Art Scroll is, of course, correct, you worded it in a very clumsy at best and misleading at worst manner. You should have raised the issue of the Hebrew at the beginning of your criticism. Also to say the translation is incorrect when in fact it is the correct translation of the song and what you meant is that it is not the translation of the incorrectly worded Hebrew is again misleading. Had I been editor of your post, I would have noted in the margin “Unclear and potentially misleading. Rewrite.”

Sorry, I misunderstood. Thanks for your patience

The point is that the way the hebrew is vowelized should be translated as “from all who see”, which is indeed incorrect. In order to mean from the one who see all, the intended meaning, it needs to be vowelized with a holam.

The phrase means, literally, “The All-seeing.”

tomatoes…..

Thanks once again for a great post.

What about Paul of Burgos? Was he not originally rabbi there?

I’m not finished ….

I wrote a comment several days ago regarding the translation of וכל בשלש, and words in the comment must have tripped an algorithm somehow, because the comment got held up for review, I’m not sure why.

Just after I posted the comment I realized I had mistakenly translated the word גבעות, and I posted a correction, and my ‘correction’ is now hanging with nothing to apply to.

Seeing that several days have passed and my original comment has not appeared, I’m reposting it (but with some corrections):

It seems that translating וכל בשלש as “comprehend” doesn’t fit the sentence well, since all of the other similarly positioned verbs in the sentence are variants of measuring. Perhaps וכל in this sentence means something closer to measurement, but we’re not aware of the root because it’s a rarely used word which we happen to not have other examples of in Tanach?

Relatedly, I’d like to think that שלש is a type of triangle or angle based measuring tool, similar to a triangle ruler, protractor or sextant (again we seem to have no other similar words in Tanach against which to measure this example). This translation of שלש would fit very well with interpreting וכל as some type of measurement, and it positions the word perfectly in the sentence, with the first reference being to water, the second to sky, and the third to earth, where earth is indeed measured using triangle/angle based measuring tools (e.g., the height and volume of mountains), and from which the sentence leads directly into weighing mountains and hills in the immediately following reference.

The full verse in Isaiah 40:12 for readers’ reference is מי מדד בשעלו מים ושמים בזרת תכן וכל בשלש עפר הארץ ושקל בפלס הרים וגבעות במאזנים.

“This was especially the case in Spain which, unlike Germany, never had a culture extolling Jewish martyrdom (and we know that large numbers of Spanish Jews chose conversion over death).”

Bizarrely, Jewish Action ran an article in 2017 extolling the “spiritual strength” of the Jewish woman by approvingly relating historical examples (complete with Brothers Grimm-esque dialogue) of mothers killing their own children in the face of forced conversion. This was at best a tragic bedieved, but in all probability it was misplaced piety resulting in cold-blooded murder. Maybe a topic for a future post?

https://jewishaction.com/religion/women/true-power-jewish-woman/

SEE RITVA IN AVODA ZARAH WHO DISAPPROVES OF KILLING CHILDREN IN ORDER TO SAVE THEM FROM SIN BUT WRITES ON RABBEINU TAM “KVAR HORAH ZAKEN” APPROVING. NOT ALSO THAT THE FAMOUS DAAS ZEKEINM IN PARASHAS NOACH IS CITED COMPLETE AS IS IN BEIS YOSEF

)SORRY BUT DONT HAVE SEFARIM IN FRONT OF ME)

HENCE A LITTLE HUMILITY IN CALLING IT COLD-BLOODED MURDER

Maybe calling it cold-blooded murder is a bit harsh – even if they were wrong, they were still “anusim” (though I seriously doubt they had the Daas Zekeinim and Rabbeinu Tam in mind when they did it!).

My main objection was with JA’s weird glorification of it, without mentioning those poskim – most, I believe – who forbade it.

On the issue of the correctness of martyrdom of children, see Haym Soloveitchik’s Collected Writings vol. I, pp. 242-4 and vol. 2, chapter 11.

Yes. He views the Rabbeinu Tam as being very much in the minority, more engaging in more like a backward-looking justification for the acts.

Hi Marc,

I love your articles. Are you going to respond to the takedown of your book in the latest issue of Dialogue?

Hardly a “takedown.”

I will, as it is really slanderous.

What could possibly be slanderous about a thorough, well-researched presentation? There may be disagreements and responses, but nothing slanderous.

Plenty. Did you read the article in question?

Any idea where your response will appear?

On the Seforim Blog. I don’t have online access.

The primary issue is not how to read particular sources (although I will of course deal with that). The central issue is that he accuses me of mocking Torah sages, of calling the Rambam a liar, of thinking I know better than the Rambam and so many others, and of trying to prove the Rambam wrong (as if my book has anything to do with this). Stay tuned.

He also says that I cited primary sources from secondary sources without examining the original, which is a completely false accusation.

As opposed to every charedi attack on Norman Lamm ever, which all cited the same secondary source.

Marc: Any way of getting access to the review on-line?

Ditto

Apparently, the contents of Dialogue are a highly-guarded state secret.

Rabbi Grossman sent me a copy of his article and gave me permission to share it, but asked me not to post it online. I will be happy , therefore, to email it to anyone who requests it of me. My email is

Lawrence.kaplan@mcgill.ca

I should mention that in his article Rabbi Grossman briefly criticized a point I made, cited by Marc, about the Rambam’s eighth principle. In a letter to me Rabbi Grossman elaborated on his criticism, to which I replied in a response. However Rabbi Grossman asked me to keep our correspondence confidential, and I am honoring his request. Which is not to say that I won’t publicly respond to his criticism as formulated in his article.

It is available here:

https://notorthodox.blogspot.com/p/in-recent-years-there-have-been-many.html

I would be more concerned about another “take down” – by Rabbi Shmuel Phillips in his Judaism Reclaimed: Philosophy and Theology in the Torah – published recently. He has a couple of chapters there critiquing your book and one he’s just made available on his website http://www.JudaismReclaimed.com which has been spreading via Facebook. Are you aware about this one and do you plan responding to it?

I enjoyed this and foundit helpful.

Are you gonna to share more about this topic? I suspect you might be reluctant to share some of your polarized opinions, but I for one, love reading them!