R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin and Yeshiva Students being Drafted to the Army, views of women, and more

Shlomo Yosef Zevin and Yeshiva Students being Drafted to the Army, Views of Women, and More

Marc B. Shapiro

1. In an earlier post I wrote about R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin and the famous essay about how yeshiva students need to serve in the army, an essay which is widely attributed to him. See here. In the post I cited important information uncovered by David Eisen that complicates the issue (as we see the Zevin family itself is of two minds on the matter), and we were left with no absolute proof that R. Zevin wrote the essay. I encourage all readers interested in the topic to read the six emails from Eisen quoted in my post, as they became the primary source material for all who wish to explore this matter.

One of the points that Eisen’s sources disagree about is when the essay was attributed to R. Zevin. R. Nachum Zevin, R. Zevin’s grandson, claims that it was only attributed to him after R. Zevin’s passing in 1978, but R. Menachem Hacohen states that already in the early 1970s he had seen the essay and it was believed that R. Zevin wrote it. As Eisen reports, one of the chief librarians at the National Library told him that he believes that already in the 1960s the essay was attributed to R. Zevin.

I am now able to put the matter to rest and establish beyond any doubt that R. Zevin is indeed the author of the essay. One of R. Zevin’s close friends was the author R. Zvi Harkavy, who served as an army chaplain. Harkavy regarded R. Zevin as his teacher, referring to him as מו”ר. In 1959 it was announced that Harkavy would publish a bibliography of all of R. Zevin’s writings, which were estimated to be over 1000 items, including material written under a pseudonym.[1] As far as I can tell, this never appeared. In Harkavy’s Ma’amrei Tzvi, p. 26, he includes a 1969 letter he received from R. Zevin is which Harkavy is addressed as ידידי הדגול. I mention all this only to show that when Harkavy speaks about R. Zevin you rely on what he says.

It has often been said that the identification of R. Zevin with the essay on yeshiva students and the army was only made years after its 1948 appearance, and this casts doubt on it having been being written by R. Zevin. I can now say that this is incorrect. In 1951 (Iyar 5711) Harkavy published an article in the Jerusalem Torah periodical Ha-Hed, which was a journal that R. Zevin himself often published in. (Unfortunately, very few issues from this periodical can be found on Otzar haChochma.) In Harkavy’s article he identifies R. Zevin as the author of the essay. Not only was Harkavy, because of his close friendship with R. Zevin, in a position to know that he wrote it, but R. Zevin never denied authorship in subsequent issues of Ha-Hed.

This shows without any doubt that R. Zevin is the author of the essay, and from this point on no one—including members of the family—should deny his authorship. Here is Harkavy’s article.

R. Nochum Shmaryohu Zajac called my attention to the recently published memorial volume for R. Yehoshua Mondshine,Sefer, Sofer, ve-Sipur. On p. 327 R. Mondshine wonders why R. Zevin—whom he seems to believe was indeed the author of the essay—would have felt it necessary to keep his authorship secret. R. David Zvi Hillman suggests that R. Zevin felt that if it was known that he wrote it, he would not have been welcome at the Brisker Rav’s home. He adds that it could have also created problems with the Habad synagogue he attended, as well as with his good friend R. Yehezkel Abramsky.

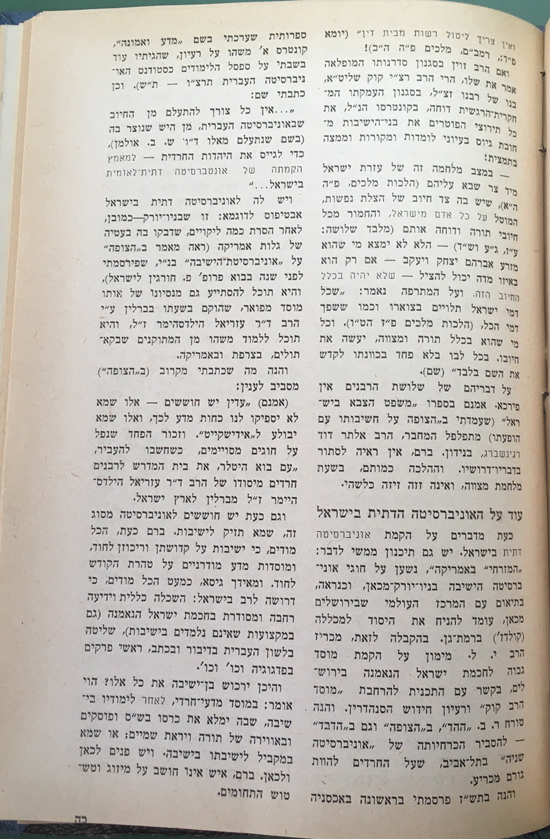

In going through the various issues of Ha-Hed, I discovered a picture of great interest in the Shevat 5711 issue.

Kitvei Ha-Rav Dr. Yosef Seliger (Jerusalem, 1930). The woman in the middle is R. Kook’s wife, Raize Rivka. Until recently I knew of only one other published picture of her, and this appears at the beginning of Pinchas Grayevski, Benot Tziyon vi-Yerushalayim, vol. 7 (Jerusalem, 1929; I think Dr. Yehudah Mirsky called my attention to this picture). The woman on the left is Miriam Berlin, the widow of R. Naftali Zvi Judah Berlin. I do not know of any other published pictures of her.

Shimon Steinmetz called my attention to this additional picture of R. Kook’s wife that can be found here.

2. In my post here I discussed these words from Exodus 15:16:

בִּגְדֹל זְרוֹעֲךָ יִדְּמוּ כָּאָבֶן

However, I neglected to mention one additional point. How come there is a dagesh in the כ when according to the grammatical rules it should not be there? R. Aaron of Lunel in his Orhot Hayyim offers an explanation. He states that if there was a dagesh people would read the last two words as יִדְּמוּךׇ אָבֶן, “stones are similar to you,” which is not a respectful thing to say to God.[2]

3. In my last post here I discussed the Hazon Ish’s opinion on the dispute between Maimonides and Rabad about an unwitting heretic, and the Hazon Ish’s assumption that Maimonides actually agreed with Rabad in this matter. It must be clarified that the Hazon Ish is not certain about his suggestion that there was no disagreement between Maimonides and Rabad when it came to someone who was completely “innocent” in his heresy. The Hazon Ish4. A couple of years ago in my post here I mentioned that in part two of the post I would have an excursus on the nature of women. For some reason I forgot to include this excursus in all the subsequent posts, so here it is.[4]

On the matter of the creation of women, and whether they are created “better” or “worse” than men, Shaul Regev calls attention to a strange comment by R. Jacob Matalon, Toldot Yaakov (Salonika, 1597), p. 7d (printed together with his She’erit Yaakov).[5] There are many comments in rabbinic texts that have a negative view of women, and most of these comments are based on a belief that women are inherently inferior to men. Yet not many texts are as explicit as R. Matalon in regarding women as almost a different species, standing between apes and men.

ובין החי למדבר הקוף ובין הקוף םמדבר [צ”ל למדבר] ומשכיל הם הנשים והאנדרוגינוס

Women obviously speak, so מדבר must mean speak with intelligence.

A passage similar to what R. Matalon says, but without mention of an ape, is found in Gersonides’ comment to Genesis ch. 3 (p. 110 in the Ma’aliyot edition).

והנה קראה האדם שם אשתו ‘חוה’, כאשר השיג בחולשת שכלה, רוצה לומר שלא עלתה מדרגתה על שאר הבעלי חיים עילוי רב, ואם היא בעלת שכל, כי רוב השתמשותה אמנם הוכן לה בדברים הגופיים, לחולשת שכלה ולהיותה לעבודת האדם. ולזה הוא רחוק שיגיע לה שלמות השכל, אלא שעל כל פנים היא יותר נכבדת מהם, וכולם הם לעבודתה

Gersonides is known for his negative view of women, and this reputation comes from passages like this. Here Gersonides states that women are on a higher level than animals, but not by much. Furthermore, just like the animals are at the service of women, so women’s role is to serve men. In discussing this passage, Menachem Kellner writes: “Gersonides apparently found Darwin’s missing link: woman!”[6]

For another explanation which Modern Orthodox women will probably regard as insulting, but more traditional women will probably see as a compliment, see R. Meir Mazuz, Bayit Ne’eman, no. 52 (parashat Terumah 5777), p. 1, who quotes R. Nissim Gaon as follows: The verse in Proverbs 1:8 states: אל תטוש תורת אמך – “Forsake not the teaching of thy mother”. Yet since women don’t have Torah knowledge, תורת אמך cannot mean this. Rather, it means the special holiday foods that the mother makes.

Readers can correct me if I’m wrong, but I do not believe that R. Mazuz’s understanding is correct, and I think R. Mazuz was citing R. Nissim from memory. That is, R. Nissim’s comment has nothing to do with women lacking Torah knowledge and identifying their cooking as תורת אמך. Rather, he cites the verse simply as a general statement about the importance of tradition. Here is the passage of R. Nissim Gaon as cited by R. Maimon the father of Maimonides.[7]

וכתב רבינו נסים במגילת סתרים כי כל מנהגי האומה באלו המנהגות כמו זה. והראש בראש השנה, החלב בפורים ובמוצאי פסח, והפולים ביום הושענא רבה. ואותם המנהגות אין לנו לבזותם ומי שהנהיגם זריז ומשתדל הוא כי הם מעיקרים נעשים ולא יבוזו במנהגי האומה וכבר אמר הנביא ע”ה ואל תטוש תורת אמך, דת אומתך אל תעזוב

Regarding the role and responsibilities of women, R. Mazuz has another interesting comment.[8] As part of his argument that women are not obligated in hearing parashat Zakhor, he says that this commandment is connected to the commandment of destroying Amalek, and women are not able to do this. How do we know that women cannot destroy Amalek and therefore are not commanded in it? “Because if she sees blood and even if she sees a mouse she becomes afraid, so how could she kill Amalek?” While many will not appreciate what they see as R. Mazuz’s flippant tone (which is obviously a joke, as he is well aware that there are women soldiers and doctors), do even feminists wish to claim that killing comes as easy to women as to men? Do they really want to be “equal” with men in this matter? I, for one, have always assumed that if women were running the world, there would be many fewer wars, as only someone who is blind to reality cannot see that men are naturally more inclined to violence than women.

Here is another interesting point relevant to the subject of women: Rashi, Menahot 43b s.v. היינו, in explaining the talmudic passage dealing with the blessings that a man recites in the morning, states that a woman is to regarded as a maidservant to her husband (i.e., to do his wishes), much like a slave is to his master: דאשה נמי שפחה לבעלה כעבד לרבו

Rashi’s comment is not surprising and has often been quoted. Indeed, although it will trouble modern readers, lots of similar comments can be found in rishonim and aharonim.[9] Furthermore, in at least three places the Talmud refers to a wife with the term shifhah.[10] Yet for a reason I can’t explain, R. Moshe Feinstein was very troubled by this comment of Rashi, and this led him to write something quite problematic.[11] See Dibrot Moshe, Gittin p. 511 (also in Iggerot Moshe, vol. 9, Orah Hayyim no. 2):

ולולי דמסתפינא הייתי אומר שצריך למחקו דח”ו לרש”י לומר דברי הבל כזה, דמן התורה הא ליכא שום שעבוד על האשה לבעלה חוץ מתשמיש ולענין תשמיש הוא משועבד לה יותר דהא עליו איכא גם איסור לאו . . . ואינה מחוייבת לעשות רק עניני הבית ולא עבודת שדה ומעט עשיה בצמר שהיא מלאכה קלה ממלאכות שדרכן של בנות העיר בזה

R. Moshe states that in no way can a woman be generally regarded as under her husband’s authority as only in a few areas does she have obligations to him (much like he has to her). He continues to expound on the way a husband is obligated to treat his wife in order to show that she is far removed from being a maidservant.[12] This is all true, and it would be easy to quote authorities who write similarly. Yet they did not see this as in any way contradicting Rashi’s statement. Understandably, some have expressed great surprise upon seeing how R. Moshe refers Rashi’s comment as הבל (as they do not accept R. Moshe’s point that Rashi could never have said דאשה נמי שפחה לבעלה כעבד לרבו).

R. Shlomo Aharon Gans goes so far as to say that if thegadol ha-dorhad not been the one to say this, it would be forbidden to write such a thing. He adds the following, bringing support for the notion expressed in Rashi that a wife is like a maidservant (not that she is a maidservant, but she is like one)[13]:

ולא הבנתי דהא הויא קנין כספו, ועי’ תורא”ש קידושין ה’ דהוא מושל עליה ומשעובדת לו וכדכתיב והוא ימשל בך, וא”כ מאי קשיא ליה כ”כ בדברי רש”י אלו

This conception, that a wife is like a maidservant, was actually criticized by R. Hayyim Hirschensohn who called attention to the “barbaric” way Jews treated their wives in the small towns of Galicia, where the wives did not even eat at the same table with their husbands.[14]

וה’ יסלח לו כי ההרגל הרע של בני מדינתו להתגאה על נשותיהן אשר לוקחים אותן רק לרקחות וטבחות ואין מסיבות בשלחן עם בעליהן וחושבים אותם כחמת כו’ [מ”ש: ראה שבת קנב ע”א] ואלמלי עלמא צריכי להו היו בעי רחמי דלבטלי מן העולם ח”ו, ההרגל הפראי הזה אשר בעירות הקטנות בגאליציא ובקצת ערי פולין גרם להרב הנז’ לבלי להרגיש את העלבון אשר עלב לבנות האבות והאמהות אשר קמו גם הן לאם לבנות את בית ישראל

As a curiosity, it is worth noting the opinion of R. Menasheh Klein that a husband should not help his wife with household tasks such as cleaning the dishes, as that is “women’s work”, while the husband works outside the home. (And what about when the wife also works outside the home?) Instead, the husband should use that time for learning Torah and other spiritual pursuits.[15]

כי לכן נתן לו הקב”ה אשה לאדם שיהי’ לו לעזר שתעשה לו צרכי הבית והוא יהיה פנוי בזמן שיש לו ללמוד תורה ולעבודת השם ולא לכבס ולהדיח הכלים אחרי האכילה ולסדר את המטות החיוב על הבעל לפרנס את אשתו ובניו ושאר הזמן כל רגע ורגע ינצל ללימוד התורה ולעבודת השי”ת שמו. ובעונ”ה נשתנה הוסת שהבעלי בתים הצעירים נעשים בעלת בתים מבשלים ומדיחים הכלים והולכים לחניות לקנות צרכי הבית איינקויפען בלע”ז בקיצור עושים כל מלאכת הנשים והנשים עושים מלאכת האנשים

I can only imagine what the reaction of a newlywed wife would be if her husband would tell her that no, he has no plans to help clean the table and do the dishes because that is women’s work.

Related to this is the following story told by R. Yosef Wineberg, the grandson of the Slonimer Rebbe. It is obviously designed to make the “Litvish” look bad.[16]

A newly married Litvishe couple was once sitting together. The wife asked her husband to please make her a cup of tea. He immediately jumps up, puts on his hat and jacket and walks out the door. About an hour later, the husband returns home, removes his hat and jacket and makes her a cup of tea. Puzzled by his strange behavior, she asks for an explanation.

He explains: when you first asked me to make you a cup of tea, I was upset. I am a Talmid Chacham, a scholar, and you are meant to “serve” me, not the opposite. Not wishing to get into an argument, I went to my Rav to ask him what I should do.

The Rav explained to me that “ishto k’gufo”, that the Halacha considers us like one person. Therefore, making tea for you is identical to making tea for me. As I feel no compunctions with serving myself, I returned home to fulfill your request.

In order to show that the husband is the boss of the household, R. David Kimhi states that while the husband calls his wife by her name, the wife does not call her husband by his name, but by some title which shows his superior status.[17]

כי האיש הוא הקורא לאשתו בשמה ולא האשה לאישה, אלא דרך כבוד בלשון אדנות קוראה לו ולא בשמו, כי כל מי שיש לו מעלה אל אחר אין ראוי לאשר למטה ממנו לקרוא אותו בשמו, כמו אביו או רבו או אדניו . . . וכן האשה לבעלה כי אדניה הוא כמו שאמר: והוא ימשוך בך

One of the proofs he offers for this idea is that in Genesis 17:17 Abraham refers to Sarah by her name, but in Genesis 18:13 Sarah refers to Abraham as “my lord” (אדני). Another proof he mentions is that when God changes the names of Abraham and Sarah he says to Abraham (Gen. 17:15): “Thou shalt not call her name Sarai.” From this we see that Abraham called his wife by her name. However, when Abraham’s name was changed the Torah states (Gen. 17:5): “Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram.” Sarah was not told this, Radak states, as she didn’t refer to her husband by his name. This was rather a general statement, that among those people who call Abraham by his name, they no longer would do so.

Although Radak states that a husband calls his wife by her name, we know that this was not always the case. Thus, we are told that R. Jacob Moellin in speaking to his wife would not call her by her name. When he referred to her in conversation with others, he would call her mein hausfrau (my housewife).[18] The text that records this information notes that already in the Talmud, Shabbat 118b, we find that R. Yose referred to his wife as “my house,” and I think most assume that this was done as a term of respect.[19] The text further notes that the general practice was that both husband and wife did not refer to each other by their first name. Such a practice was also found in the Sephardic world.[20] What this shows us is that contrary to what Radak records, the practice need not have anything to do with the husband being regarded as “superior” to his wife.

With all the discussions in rabbinic literature that show the essential differences between men and woman, let me mention another curiosity that, if you want to be cute, you can say that in one place the Talmud actually refers to women as men. I have in mind Zevahim 67b which, in discussing the burnt offerings brought by two women after childbirth, states:

חטאת לזו ועולה לזו עשה שתיהן למעלה . . . אימור דא”ר יהושע בחד גברא בתרי גברי מי אמר

In this passage, the word גברי, which means “men”, refers to the case of the two women (although the principle enunciated applies to all people).[21]

While on the male-female topic, let me mention something else that is relevant. We all know that the name Avi (short for Avraham) is quite popular. Yet how many know that this is already a biblical name, but used for a woman (2 Kings 18:2)?

I want to return to the notion already mentioned in this note, and found in a number of earlier works, that an ape stands between animals and humans. The Sefat Emet, Genesis 18:1, expands on this as follows:

ובין חי למדבר קוף. ואנו נאמר כי אחר מדבר אדם, שעל זה נאמר “אדם” אתם קרוין אדם ולא האומות. וישמעאל הוא הממוצע לכן נקרא פרא אדם, ולכן יד כל בו וידו בכל, כי על ידו יש התקשרות בין מדריגות מדבר למדריגת אדם

When he writes כי אחר מדבר אדם it means that after the level of מדבר, which means “humanity”, there is the level of אדם, which is the level of the Jewish people. He then adds that the Arabs stand between מדבר and אדם which is why they are called פרא אדם. Often פרא אדם is used to show that the Arabs are on a lower level than other nations. However, here we see that the Arabs are on a higher level, and closer to the Jews than the other nations, as among the nations of the world only the Arabs are also called אדם—no doubt because of their monotheism, see Yevamot 61a—even if this word is placed together with the negative term פרא.

The Sefat Emet’s comment is derived from the Zohar,[22] which explains פרא אדם as meaning one who possesses the “beginnings of אדם”. The Zohar also places the descendants of Ishmael on a higher level than the other nations because they are circumcised. Circumcision was widely practiced even in pagan Arabia, so the reference to circumcision alone would not be enough to date this passage of the Zohar to the post-Islamic period.

R. Jacob Emden, however, cites a different passage in the Zohar that assumes the existence of the Islamic world, meaning that it could not have been written by R. Shimon ben Yohai.[23] He writes:

הנה לפניך שבימי בעל ספר הזוהר כבר היתה אמונת מחמד הישמעאלי בעולם (שנתחדשה בימי אמוראים האחרונים על”ב) כי קודם זמן זה היו כל הישמעאלים עובדי אלילים גמורים, ככל יתר גוי הארצות.

R. Emden also cites another Zoharic passage that assumes Islamic rule in the Land of Israel. He comments:[24]

הרי כי בימי בעל ספר הזוהר היתה אומת ישמעאל שולטת בארץ הקדושה, ודבר ידוע הוא ומפורסם, שלא הגיעו הישמעאלים לממשלה כללית עד שנת שע”ד לאלף החמישי . . . נמצא עכ”פ יותר מחמש מאות שנה אחר רשב”י חובר ספר הזוהר, ואולי מאוחר עוד הרבה מזה, ואיך אפשר להסכים זה עם שמות האומרים אותם הדברים, והמה חבריו או תלמידיו של רשב”י, לפי המובן בלשונו של בעל ספר הזוהר, הלא זה כדבר שאין לו שחר

He cites a third such example and writes:[25]

מלכות ישמעאל לא נתפרסמה ולא נתפשטה בימי תנאים ואמוראים. כי היו אז ממלכה שפלה קטנה וירודה

Returning to the matter of how women have been viewed, R. Joseph Solomon Delmedigo mentions that jokers—ליצני הדור—come up with all sorts of gematrias. When it comes to women not all of them are negative. For example, the gematria of אשה is דבש, and אשה יפה = שמחה גדולה. However he also cites a gematria which is not very complimentary to women. זכר=ברכה and נקיבה=בקללה. R. Delmedigo sees this as a big joke, but it is actually mentioned by R. Hayyim the brother of the Maharal in his Iggeret ha-Tiyul, section ז, and it is also found in Ba’al ha-Turim, Gen. 1:27 (with some differences as to which letters are actually included in the gematria).

In 1807 R. Jacob Samson Shabbetai Senigallia[26] published his talmudic commentary Shabbat shel Mi. Here is the title page of the Livorno first edition. (It has been reprinted a number of times).

Here is what appears in the book on p. 89b. He is trying to explain why chapters 5 and 6 in tractate Shabbat are next to each other. Chapter 5 begins במה בהמה and chapter 6 begins במה אשה, and according to R. Senigallia this is because “birds of a feather flock together.”

If he was trying to make a joke, I can understand what he wrote. But who ever heard of making a joke in the middle of a talmudic commentary? Presumably, he was being serious, which leaves us with a very offensive comment.

There is, to be sure, humor in the Talmud, but I don’t know of any examples in talmudic commentaries. Yeshayahu Leibowitz quipped that the Sages must have had a good sense of humor, since they included the following text in the Talmud [27]: תלמידי חכמים מרבים שלום בעולם. In all seriousness, however, there are indeed humorous passages in the Talmud, as pointed out by R. Moses Salmon.[28] Here is one example he gives (Bava Batra 14a):

The Rabbis said to R. Hamnuna: R. Ammi wrote four hundred scrolls of the Law. He said to them: Perhaps he copied out the verse תורה צוה לנו משה

R. Salmon claims that anyone with a bit of sense can see that R. Hamnuna’s reply is a wisecrack made in response to the obvious exaggeration about R. Ammi.

Nehemiah Samuel Libowitz states that even in the Zohar we have passages that show a humorous side.[29] One of the many examples he points to is Zohar, Bereshit, p. 27a:

וימררו את חייהם בעבודה קשה בקושיא. בחומר קל וחומר. ובלבנים בלבון הלכתא. ובכל עבודה בשדה דא ברייתא. את כל עבודתם וגו’ דא משנה

I have no idea what to make of the following comment from R. Oury Cherki, dealing with humor, which does not sound like something that would be said by a leading kiruv figure (De’ah Tzelula: Olam ve-Adam be-Mishnat ha-Rav Kook [Jerusalem, 2015], p. 246). Rather, it sounds like something one of the maskilim of old would say.

התורה שבעל-פה אינה מובנה ללא שותפות רוח האומה. לכן כשלומדים הלכה רצוי להצטייד בחוש הומור, שכן לפעמים הדברים נראים משונים למדי. למשל, הכנת כוס תה בשבת. התלמוד אומר שאסור לשפוך מים קרים לתוך החמים אבל מים חמים לתוך הקרים מותר, כי יש כלל ש”תתאה גבר”, התחתון גובר. כששופכים מים חמים לתוך הקרים המים הקרים מתחממים ומתבשלים מה שאין כן ההפך – המים החמים מתקררים. יש כאן בהחלט סוג של הומור

I also found the following interesting comment by Moshe Meisels, the editor of Ha-Doar, in a letter to Chaim Bloch.[30] He suggests that the talmudic prohibition against a non-Jew observing the Sabbath is an example of rabbinic wit, and is not to be understood literally.

ואגב, לא אהא בבחינת מורה הלכה לפני רבו אם אינני מתאפק מלהביא מעין חידוש שנתחדש לי הקטן באחד המאמרים התמוהים בתלמוד מן הסוג הנ”ל, והוא אמרם: עכו”ם ששבת חייב מיתה, שנאמר יום ולילה לא ישבותו וכו’. ואין צורך להרבות דברים על הזרות שבדבר: מה איכפת למי אם שבת או לא שבת, ומה היא הראיה מאותו פסוק, המוסב על קיץ וחורף וכו’, ומה ענינו לכאן ולעכו”ם דוקא? ונראה לי שכל המאמר בא בדרך חידוד, וזה מובנו: עכו”ם ששבת מן הדין שיהא חייב מיתה בדיניהם. מדוע? ישראל שלא שבת חייב מיתה, משום שעל א-לוהיו נאמר וישבות ביום השביעי וכו’, אבל עובד כוכבים ומזלות, שעליהם נאמר יום ולילה לא ישבותו, מן הדין שעובדיהם יהיו חייבים מיתה אם שינו מדרך אלהיהם ושבתו

On the matter of non-Jews observing the Sabbath, R. Yaakov Koppel Schwartz makes a fascinating suggestion, which he acknowledges has no support in the rishonim and therefore he has doubts whether it is correct.[31] The prohibition against labor on the Sabbath is in remembrance of the fact that we were slaves and God redeemed us. Therefore, it is understandable why non-Jews are forbidden to commemorate the Sabbath by abstaining from work, as this has no connection to them. However, there is another reason given for the Sabbath and that is so that we remember the creation of the world. Non-Jews are also supposed to acknowledge this and therefore there should be nothing wrong with non-Jews having some sort of celebration in honor of the Sabbath.

אבל הכיבוד והקידוש של יום השבת, שהוא משום אמונת חידוש העולם, שייך שגם הגויים יהיו בהם ואינם מנועים מלכבד ולענג את השבת

If we follow R. Schwartz’s approach, this is something that could be suggested for Noahides whose “religion” is lacking any rituals, which for most people is an essential component of their religion.

* * * * * * * *

[1] Ha-Tzofeh, June 16, 1959, p. 2.

[2] Orhot Hayyim, Or Etzion ed. (Merkaz Shapira, 2017), p. 106, quoted by R. Joseph Karo, Beit Yosef, Orah Hayyim 51 (end). Regarding negative expressions directed against God, there is an interesting passage in R. Yedidiah Solomon Raphael Norzi, Minhat Shai, Deut. 8:3. To understand it one must know that the old French word “fi” expressed disdain or disgust. See here. The issue Norzi discusses is that the verse reads:

‘כִּי עַל-כָּל-מוֹצָא פִי-ה

Norzi cites a view that in this case there should be a dagesh in the word פי even though that is not in accord with the general rule, because without the dagesh, reading it as “fi” would be disrespectful to God:

כי לשון גנאי הוא בלשון צרפת וחלילה לשם יתברך

Norzi completely rejects this and states that the rules of biblical grammar are not to be changed because of how words sound in languages other than Hebrew (and there are indeed examples where biblical Hebrew words sound like profanity in other languages).

ואין לנו לחוש ללשון צרפת שאין מבטלין דרכי לשון הקדש מפני שאר לשונות

See also Samuel David Luzzatto, Prolegomena to a Grammar of the Hebrew Language, trans. Aaron D. Rubin (Piscataway, N.J., 2005), pp. 133-134.

Regarding the pronunciation of פ, R. Meir Mazuz points out that the Vilna Gaon, Commentary to Tikunei Zohar, section 19, p. 38d (p. 166 in R. Zuriel’s edition), mistakenly believed that Sephardim pronounce פ with and without a dagesh the same way (just as they pronounce ת with and without a dagesh the same way). R. Mazuz notes that the Vilna Gaon’s point is repeated by R. Baruch Epstein, Mekor Barukh, vol. 1, p. 397b (without mentioning the Gaon). See Mazuz, Bayit Ne’eman (Humash), vol. 1, p. 13 (first pagination).

[3] Hazon Ish, Yoreh Deah 62:21.

[4] In my earlier post I cited R. Samson Raphael Hirsch as adopting the notion that women are created on a higher spiritual level than men. I neglected to note that Shaye J. D. Cohen earlier discussed Hirsch’s approach. See Cohen, Why Aren’t Jewish Women Circumcised (Berkeley, 2005), pp. 165ff.

[5] “Eshet Hayil: Kavim li-Demutah u-le-Ma’amadah shel ha-Ishah be-Hagut ha-Yehudit ha-Shesh Esreh,” in Ephraim Hazan and Shmuel Refael, eds. Mahbarot li-Yehudit (Ramat-Gan, 2012), p. 286.

[6] Torah in The Observatory (Boston, 2010), p. 287. I earlier discussed Ralbag here.

[7] See R. Yaakov Moshe Toledano, Sarid u-Falit (Tel Aviv, [1945]), p. 8.

[8] Bayit Ne’eman no. 153 (parashat Vayikra 5779), p. 2.

[9] See e.g., R. Israel Ibn Al Nakawa, Menorat ha-Maor, ed. Enelow, vol. 4, pp. 32-33, who instructs a wife as follows (using the word שפחה that so troubled R. Moshe):

ועושה צרכיו בעצמה ולא על ידי אחרים. ואפי’ היו לה כמה עבדים וכמה שפחות, תעמוד היא ותשרתנו, ותקראנו אדוני . . .ויהיו עיניה תלויין לו, כעיני שפחה אל יד גבירתה

For a translation of this passage, see here. Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Ishut 15:20, says that a wife should regard her husband כמו שר או מלך.

Radak, Gen. 3:16, writes:

והוא ימשול בך: לצוות עליך מה שירצה כאדון על עבד

Ramban, Gen. 3:16, explains that as a result of Eve’s sin, the relationship of man and woman was changed. From that point on:

והוא יחזיק בה כשפחה ואין המנהג להיות העבד משתוקק לקנות אדון לעצמו אבל יברח ממנו ברצונו

R. Bahya ben Asher, Gen. 3:16, writes:

ואל אישך תשוקתך: שאע”פ שהאשה משועבדת ברשות הבעל ומנהג העבד לברוח מן האדון כדי שלא ישתעבד, גזר בזאת שתהיה משתוקקת לבעל ושתרצה להשתעבד לו בהפך מן המנהג

See also R. Chaim Rapoport’s letter in my Iggerot Malkhei Rabbanan, p. 172.

R. Avraham Blumenkrantz, Gefen Poriah, p. 352, quotes approvingly another rabbi who states as follows (emphasis added):

Her tears are ever ready to flow at the most miniscule suggestion of being dealt with as a maidservant. She will concede you the service of והוא ימשל בך. She will consent to call you בעלי, but don’t accent the דגש in the בית too heavily. She must constantly be reassured that there is honor and dignity in her subservience. Honor her more than you honor yourself. She must be compensated for her subjugation, and be made to feel that she has a genuine share in the dignity of the throne.

Do haredi women really feel that they are subservient or subjugated? Do haredi men feel this way about their wives? Hasn’t haredi society accepted the notion of separate but equal when it comes to men and women?

[10] Sanhedrin 39a, Yevamot 113a, Nedarim 38b.

[11] As is well known, and I have written about previously, R. Moshe often rejected the authenticity of texts that he found problematic. Another example of this with regard to Rashi on the Talmud is found in Iggerot Moshe, Even ha-Ezer, vol. 4, no. 64:1. Here R. Moshe says to delete words in Rashi even though, as he notes, these words are found in “Rashi” on the Rif and in R. Nissim. See the strong responses to R. Moshe quoted in R. Yonason Rosman, Petihat ha-Iggerot, pp. 605-606. One of these responses is from R. Menasheh Klein in his notes to R. Eyal Shraga, Minhat Ish, vol. 1, pp. 302-303. R. Klein writes:

וח”ו ואטו עד כמה נילך ונמחוק בדברי רבותינו ז”ל שנאמרו ברוה”ק, ולולי דמספינא הייתי אומר דאיזה תלמיד טועה כתבו, אבל פשוט דדברי רש”י נכונים וליכא כאן טעות כלל

When R. Klein suggests—לולי דמספינא—that a “mistaken student” is responsible for the problematic passage in Iggerot Moshe, he does not mean it seriously. This is just his respectful way of saying that R. Moshe’s position is completely without basis. He uses the same language in Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 12, Yoreh Deah no. 214. There he responds to R. Moshe’s statement that he doesn’t know who R. Menahem Tziyoni is, but since he quotes a heretical—in R. Moshe’s opinion—passage from R. Judah he-Hasid’s commentary on the Torah, therefore R. Tziyoni’s work must be banned together with R. Judah he-Hasid’s commentary.

[12] R. Moshe also famously states that women do not have any less holiness than men. See Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim vol. 4, no. 49 (p. 81). See also the new Mesorat Moshe, vol. 4, p. 476. This position is at odds with many earlier writers who saw men as holier because they are commanded in more mitzvot. This is also Maimonides’ position in his commentary to Horayot 3:7. See R. Chaim Rapoport’s discussion in Kovetz Hearot u-Veurim, no. 908 (2006), pp. 138ff. Yet see R. Dov Halbertal, Erekh ha-Hayyim be-Halakhah (Jerusalem, 2004), vol. 2, p. 399, who has a different approach and makes the point that just because a Kohen and Levi are to be saved before an Israel, no one would say that the Kohen and Levi have more holiness. See also R. Yitzhak Barda, Yitzhak Yeranen, vol. 11, p. 249, that women are holier than men. He offers an original explanation of this notion.

שהאשה שהקב”ה הפריש ממנו, מהצלע שלו, הוא מופרש, וממילא כל מופרש קדוש, ואז האשה יותר קדושה מהאיש. ובזה מובן למה האיש מקדש את האשה, לא אומר לה הרי את אשתי, או כל סממן לשון של נישואין, חברה או שותפה וכו’, זולתי: הרי את מקודשת לי! לפי שהקב”ה קבע כל מופרש קדוש

[13] Kinyan Shlomo, Yevamot, p. 89. See also R. Natan Einfeld, Minhat Natan: Kiddushin, pp. 139-140, who cites other sources in rejecting R. Moshe’s point.

[14] Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 4, p. 50a. See R. Menasheh Klein, Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 12, no. 351, for a defense of the practice of husbands and wives eating separately.

[15] Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 7 no. 155 (called to my attention by R. Aviad Stollman).

[16] The story is recorded by R. Chaim Dalfin, Faces and Places Boro Park (Brooklyn, 2017), p. 149.

[17] Commentary to Gen. 17:15. See the rejection of Radak’s opinion in R. Betzalel Stern, Be-Tzel ha-Hokhmah, vol. 1, no. 70.

[18] Maharil, Likutim (p. 610 in the Makhon Yerushalayim edition).

[19] On the other hand, R. Meir Schiff (Maharam Schiff), Gittin 52a, explains that R. Yose referred to his wife this way because she was a bad wife: אשה רעה. Yet the proof he brings for this is actually from a different R. Yose. See R. Judah Leib Maimon, ed., Sefer ha-Gra, vol. 1, p. 110 in the note. Regarding “bad wives”, R. Elazar of Worms is quoted as follows in R. Alexander Suslin, Sefer ha-Agudah, ed. Brizel, Yevamot, no. 78 (p. 41):

מי שיש לו אשה רעה יסבול יקבל ברצון ויקבל בשמחה ולא יראה פני גהינם

What does R. Elazar mean that if you suffer under a bad wife you will not see gehinnom? R. Moses Guedemann explains that with a bad wife you already saw gehinnom in your lifetime, so there is no need to see if after death. See Ha-Torah ve-ha-Hayyim, trans. Friedberg (Warsaw, 1897), vol. 1, p. 194:

כי פני הגיהנם כבר ראה בחייו

Regarding “good wives” see R. Shlomo Hoss, Kerem Shlomo, no. 43, who writes:

אין לך כשרה בנשים אלא אשה שעושה רצון בעלה: אהע”ז ס”ס ס”ט (אך אשת חיל כזאת מי ימצא)

R. Solomon Zvi Schueck was shocked at R. Hoss’ final comment, that one cannot find a wife who does the wishes of her husband. R. Schueck writes that based on this passage he assumed that R. Hoss must not have had a good wife.

נראה לי שהי’ לו אשה רעה, וממנה דן על כל הנשים שבישראל

See She’elot u-Teshuvot Rashban, Even ha-Ezer, no. 99 (p. 88b). He further tells us that he asked one of R. Hoss’ students who confirmed that this was indeed the case.

[20] See Tuvia Preschel, Ma’amrei Tuvyah, vol. 5, p. 142.

[21] See Or Torah, Shevat 5780, p. 460.

[22] Exodus 86a, 87a.

[23] Mitpahat Sefarim, ch. 4 (at the beginning; p. 20 in the Jerusalem 1995 edition). In R. Reuven Rapoport’s edition of Mitpahat Sefarim, with his commentary Itur Soferim, p. 13, R. Rapoport sees it as obvious that this passage in the Zohar is a later interpolation much like there are Savoraic additions in the Talmud.

[24] Mitpahat Sefarim, ch. 4 (p. 27 in the Jerusalem 1995 edition).

[25] Mitpahat Sefarim, ch. 4 (p. 54 in the Jerusalem 1995 edition). Regarding the larger issue that R. Emden points to, see Ronald C. Kiener, “The Image of Islam in the Zohar,” Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 8 (1989), pp. 43-65.

[26] See the recent discussion of R. Senigallia by R. Moshe Maimon in the Seforim Blog here.

[27] Sihot al Pirkei Ta’amei ha-Mitzvot (Jerusalem, 2003), p. 289.

[28] Netiv Moshe (Vienna, 1897), pp. 45-46.

[29] “Halatzot ve-Divrei Bikoret be-Sefer ha-Zohar,” Ha-Tzofeh le-Hokhmat Yisrael 11 (1927), pp. 33-45. For more on humor in the Talmud, see Yehoshua Ovsay, Ma’amarim u-Reshimot (New York, 1946), ch. 1; Meyer Heller, “Humor in the Talmud” (unpublished masters dissertation, Hebrew Union College, 1950), available here; R. Mordechai Hacohen, “Humor, Satirah, u-Vedihah be-Fi Hazal,” Mahanayim 67 (5722), pp. 8-19; and Ezra Brand’s post here. From Brand I learned that David Lifshitz wrote an entire doctorate on the subject. See also my posts here and here where I discuss Siftei Hakhamim’s comment that Moses thought God was joking with him, and how this has been censored in a recent edition. See also J. Chotzner, Hebrew Humor and Other Essays (London, 1905); Nehemiah Samuel Libowitz, Ha-Shomea Yitzhak (New York, 1907).

[30] See here (Chaim Bloch Collection, Leo Baeck Institute, 7155-7156, 1/13).

[31] Likutei Diburim, vol. 4, pp. 24-25.

73 thoughts on “R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin and Yeshiva Students being Drafted to the Army, views of women, and more”

BH

Great post as usual. I would like to just add a few things in regards to Rav Zevin’s authorship of the article.

Rabbi Hillman responded to Rabbi Mundshein with a number of points, agreeing that the piece had been written by Rav Zevin.

He points out a number of similarities to Rav Zevins style of writing. I would just like to make note of one of his points: There are almost no linguistic errors, something which is quite rare of Rabbis!

Someone else made the following point to me, which I think is of interest:

והמובאה בשם שולחן ערוך הרב היא הנותנת, שכן מצינו שהרב זוין אזכר את כל אותן מקורות במאמרו הנזכרים יחד עם המקור בשו”ע הרב בעניין הצלת חברו במקום סכנת עצמו במאמר אחר מפורסם שלו – משפט שיילוק (נדפס ב’לאור ההלכה’), שם הוא דן בדברי הרדב”ז, הרמב”ם ושו”ע הרב

There is a picture of Basya Miriam Berlin in MiVolozhin ad Yerushalayim (vol. 1, between p. 128 and 129).

Rabbi Dovid Cohen of Gvl Yaavetz said that when R’ Moshe wrote that something is a טעות הדפוס or an insertion by an erring student, he did not mean it as a historical statement. Rather, he felt that what was said was so out of bounds that it should be completely disregarded, but phrased it this way out of respect. Incidentally, this accords with what the Meiri writes in his introduction to Avos, that when the Gemara states חיסורי מחסרא והכי קתני or תריץ ואימא הכי, they did not really mean that the wording of the mishna was corrupted, or that the mishna spoke of only that case. The amora’im were disagreeing with the mishna, but out of respect did not want to say outright that the mishna was wrong.

But does that make it better or worse? How are we to square the posek hador in the 20th century dismissing something like a dozen (more?) comments of the greatest of the Rishonim (e.g., Rashi, Ramban) as being out of bounds? And it is so out of bounds in the Ramban’s case that RMF says it’s a mitzvah to erase it from your seforim? That is nothing less than shocking and calls into question all sorts of basic assumptions we make about rabbinic hierarchy.

It should call those assumptions into question. Many of those assumptions are not based on anything. There is no hard and fast rule that later generations are totally subservient to earlier ones.

Perhaps you don’t recognize the assumptions I mean:

1. RMF is going much further than “not being subservient;” he is declaring their statements *out of bounds.* So, we are free to declare the hashkafos of Rishonim as out of bounds simply because that appears correct us? (NOT in cases when they are outside the mainstream; we can debate such cases. In the cases at hand RMF declares them out of bounds because of his own sevara.) Did RMF not believe in yeridas hadoros? Besides Maimonides (according to Kellner), I believe that is almost a universally held view among Rishonim and Acharonim. RMF simply disputed this? Furthermore, no one before RMF had such violent opposition to these statements. He knew better than *anyone* before him?

2. Reassessing assumptions cuts both ways: I can reassess my view of the RIshonim based on RMF or I can reassess my view on RMF based on the Rishonim.

I do not see this as any different from what the Meiri mentions. In fact, he also writes that the rishonim do it on occasion to the Gemara.

ועם כל זה נתמעטו הלבבות מרוב הצרות והוצרכו האחרונים לחבר אחריו דרך ביאור והרחבה ולפעמים דרך סתירה ותיקון כשהיו חכמי הדור מסכימים לכך ממה שרואים בו קושיא חזקה כמ”ש במסכת יום טוב (ל”א א’) אמר שמואל אין מביאין עצים אלא מן המכונסים בקרפף והקשו והא אנן תנן מן הקרפף כלומר ואפי’ מן המפוזר ותירצו מתני’ יחידאה היא וכן אמרו סמי מכאן כך וכך וכן אמרו פרת חטאת אינה משנה וכן בפרק החולץ (יבמות מ”ג א’) על משנת מסרק של פשתן שנטלו שניו האמורה בטהרות (כלים פי”ג מ”ח) רבי יוחנן ור”ל דאמרי תרוייהו אינה משנה וכן תמיד איתמר חסורי מחסרא כו’ וכן לאו תרוצי מתרצת לה תריץ ואימא הכי וכן הרבה כיוצא באלו *כמו שנעשה היום אף אנחנו מראשינו וזקנינו הקודמים ועוברים לפנינו ועל ראשינו* וכמ”ש דרך כלל מקום הניחו לנו כו’ כלומר שאין השלימות נמצא בנבראים ואפי’ במובחרים שבהם עד שלא יהיו אחרונים רשאין לחלוק עמהם בקצת דברים:

I am mystified how you can think disagreeing is the same thing as saying it’s a mitzvah to erase what the Rishonim wrote (or describe it as “hevel”) because it is so wrong. I don’t have a problem with Acharonim arguing with Rishonim, but that’s in a different league.

Once again, the Meiri writes that when the amora’im disagreed with the tanna’im, they “erased” what they wrote, and that when the rishonim disagreed with the amora’im they did the same.

The Amoraim are “erasing” in the sense that they are disagreeing, and that is not the halachah, no problem. RMF is “erasing” because chas v’shalom that a Jew should own a sefer saying something so kneged hashkafas hatorah. Totally not comparable, unless you’re making some gezeirah shavah “erase” “erase.” (A good way to distinguish is that RMF says iirc it’s a “great mitzvah” to erase it [because it’s kneged the Torah]. The Amoraim aren’t saying that because they are merely disagreeing – machlokes, no big deal.)

1) I always assumed what you quote from Rav Dovid Cohen, but the new מסורת משה ח”ד ע’ תקי”ח reports Rav Moshe expressing real fears of forgery etc., casting doubt on that interpretation.

2) The retort by Rav Menashe Klein is an obvious dig at Rav Moshe, rather than a respectful way of disagreeing. He’s mocking Rav Moshe’s habit of pinning anything he doesn’t like on a forger or תלמיד טועה.

I always wondered if that is how ‘hishtanu hatevaim’ is to be understood. Not that there was an actual change in nature but rather rabbinic statements so different from how science is currently understood that the earlier authorities were dealing with a different natural order

As a life-long Avi, I am not troubled by the fact that the name אֲבִי appears as that of a woman in Tanach. My name is accented on the first syllable and is vocalized with a full patah, אַבי. Those are significant differences.

In Baghdad the custom was that men and women ate in different rooms. See Ben Ish Hai 2 B’reshit 2

For whatever veracity one wishes to attach to it, Rabbi Yechiel Spero’s biography of Rav Pinchas Scheinberg (Artscoll 2013; p. 102) records that, even after his children were married, when Rav Scheinberg would return home from learning late at night, he would wash the dishes with a sefer perched atop the faucet of the sink. Apparently, unlike Rav Menasheh Klein, Rav Scheinberg held that אפשר לקיים שניהם.

Being “proactive” is good if you have nevua, or at least super-accurate insight. But for mere mortals, it’s a bad idea. Because you don’t really know what’s coming down the line and if you try to be proactive to things that you speculate may be coming, then you end up over-reacting all the time.

And in general, in a tradition-based religion and culture like Judaism, the mere act of changing anything weakens the religion, so it’s best not to change anything until absolutely forced to do so by circumstances.

And that’s how it seems to have played out. I’m not seeing any particular success from those who are more proactive vs reactive.

I have heard choshuve rabbanim argue that we have to be very cautious when making any innovations because we have to consider all possible consequences. I understand that argument, but I feel that the charedi world takes it a bit too far. Do you really believe that being proactive requires insight that is not available to any “mortals”, so our job is just to preserve the status quo? If anyone has the insight necessary to weight the benefits of making innovations against the potential consequences, it would be gedolei Yisrael (who seem to be afraid to do so for some reason I do not understand).

The choice is not between making changes or leaving things as they are. Nothing is static and many things will change in any case. If we don’t try our best to make changes that we believe will be for the good of Judaism, changes will be forced on us by outsiders and we will be forced to react.

The question is whether gedolim should be proactive and make certain takkanos, so that we frum Jews can determine the course of events to some degree, rather than have the course we follow dicatated to us by outside forces. I would much prefer that the leaders of the Torah community try to determine our course, rather than having it determined by outsiders while we go kicking and screaming in a direction that has been forced upon us.

In regard to whether being proactive works, many developments of modern frum Judaism were based on gedolim being proactive (although sometimes later than they could have been). Here is a very incomplete list: The modern yeshiva as founded by R’ Chaim Volozhiner, the mussar movement, the Bais Yaakov system, R’ Hirsch’s Torah im Derech Eretz philosophy. Would we be better off without all those innovations?

Being “proactive … later than they should have been” is called being reactive.

And this applies to most of your cited examples.

Exceptions might include the Volhozhin yeshiva. But I don’t know that this was either proactive or reactive – I don’t know if it was either in response to or in anticipation of any particular societal changes. And it wasn’t especially revolutionary in any event – I’m not aware of any reactionaries who opposed it.

The mussar movement is also hard to categorize, since its success was only after it took a direction that was not anticipated by its founder (i.e. mussar yeshivos).

I agree with you that instituting changes late can be considered being reactive, not proactive. My point was that I think we can agree some revolutionary changes that have been made in the past two centuries were positive and, if so, perhaps we can say in hindsight that they should have been implemented earlier. R’ Hirsch, for instance, is widely considered to have saved German Jewry from complete assimilation after most Jews in German cities had already left frumkeit. Perhaps if someone like him had come a generation or two earlier they would have prevented the collapse of German frumkeit, but they would probably have met with a lot of opposition and been banned.

My main point is that frum leaders should look at what is most ideal for frum society and try to make that possible rather than acting as if the status quo is miSinai and treating any improvement like bringing organs into our shuls.

If change is inevitable, then our leaders should decide how we change, not the Israeli or American government or anyone else who doesn’t share our values.

OK, but that brings us back to my original point. Which was essentially that hindsight is 20/20 but that foresight is very far from that.

FWIW, it’s also not always clear that changes which worked out well would also have been successful if done earlier. It’s well known that R’ Yisroel Salanter felt he might have more success in Germany than in Lithuania, comparing the latter situation to a stampeding horse and the former to a horse which is already a bit winded. (For all that, I don’t know that he was particularly succesful in Germany, but the point remains.)

The idea that a woman’s status may have changed over time and in the context of the community is indisputable. This is reflected by the fact that there are only two instances of plural marriage recorded among the Tanaim and Amoraim, although it was common in the Biblical era. The concept, the dynamics, of marriage, have to change over time, and there is no one true or perfect model.

I disagree with the claim that plural marriage was common in the Biblical era. If you consider the 3 patriarchs, marrying one woman was the default assumption, and additional wives were only married for specific reasons.

Moses and Aaron appear to have married one wife each. And similar, as a general rule.

In general, marrying multiple women appears to have been done mostly by kings, nobles, and such, who didn’t exist in later eras.

Why do you say that “kings, nobles, and such,” didn’t exist in later eras. There were certainly נשיאים and רישי גלותא who had considerable temporal and religious power. In any case, I think my point stands. Two is a very, very, small number. And those two that did have plural marriages did so without any thought of consummating those marriages.

At least one of them (R’ Yosi) did in fact consummate those marriages. See Shabbos 118b, ה’ בעילות בעלתי, and Tosafos there ד”ה אימא (from the Yerushalmi) that he had five yevamos and performed yibbum with each of them.

Very nice. Of course, we do not know that he they remained married after performing yibum. Additionally, it is not fair to bring in cases of Yibum, which may even supersede the Cheirem.

Source that “it was common in the Biblical era”? Other than kings, what other examples are there?

How many families are described in the Torah other than kings? But when they are, even post-diluvian, you have Elkana.

Elkana had a barren wife.

I think this discussion is sterile. To me, it is self evident that plural marriages were common in the early years of the Jewish people, and over time, they became rare. As I said, there are no recorded instances of any such households among Tannaim and Amoraim, with Rav and Rav Tarfon only using it legalistically. Most likely, it was the change from tribalism and pastoralism to nation and city that rendered such marriage archaic. Rabbeinu Gershom added the force of law to an inexorable social change.

Could be. But with males and females at a 1-1 ration, the default assumption should be against widespread plural marriages.

Re: “the talmudic prohibition against a non-Jew observing the Sabbath is an example of rabbinic wit, and is not to be understood literally.”

I have always understood that to be the position of R’ Hirsch. In Shmos 16:8 he writes:

“…No man has the right to lead women and children into a barren desert; no man has the right to order a cessation of work for one day, let alone for a whole year periodically. If God had not ordained these laws, they would be, as the prophet put it, חקים לא טובים ומשפטים לא יחיו בהם. As our sage say גוי ששבת חייב מיתה, “If a non-Jew makes it his duty to a keep a Jewish Sabbath, he commits a serious crime”.

First, he translates (I assume it an accurate translation) חייב מיתה as “a serious crime”. And his point seems to be that it would irresponsible for a person to neglect his duty towards his family by not working on Shabbos. We only have the right to do so because God commanded us to. If a non-Jew “makes it his duty” to not work one day a week then he is being negligent. He seems the understand that a non-Jew is not literally guilty of a capital punishment for keeping Shabbos, but rather guilty of the serious crime of being reckless.

Fascinating post, as always.

On the prohibition against non-Jews keep Shabbat – I doubt this is meant in humor, considering the midrash made its way into the Shabbat morning tefillah (it is a sign between G-d and the Jewish people that only they get Shabbat, even though (Ki) G-d created the entire world in 6 days). The death penalty part could be seen as humorous, or at least expressing a viewpoint of the roles of non-Jews relative to Jews in society.

With regards to someone who questions if women are “אדם”, see גלויני הש׳׳ס of Rav Yosef Engel, Sanhedrin 59a s.v. שם התם בז׳ מצוות דידהו, in the name of שו׳׳ת רד׳׳ך.

With regards to R. Yaakov Koppel Schwartz’s suggestion that the aspect of Shabbat which commemorates the creation should in theory be relevant to non-Jews, see מהר׳׳ל תפארת ישראל פרק מד (in some editions, ד׳׳ה ומעתה לא יקשה, near the beginning of the perek).

At footnote 27, you quote a book of Yeshaya Leibowitz concerning the humor of talmedei chachamim marbim shalom ba-olam. I heard that quip personally long before 2003 from Prof. Shaul Lieberman, and also read recently an attribution to R. Norman Lamm. Did Leibowitz quote a source or claim to have made it up himself. I would guess it originated long before.

He didn’t quote a source. It probably goes way back.

I’ve heard R’ Leiman say it as well.

I used to daven with the late Avraham Schechter, brother to R’ Aharon of Chaim Berlin. Once, at the end of Musaf, the chazzan said the line about talmidei chachamim out loud. This was when the whole Slifkin ban was blowing up, and when the chazan said that, R’ Schechter called out, “Not always!”

That there is humor in the Talmud is certain. It exists in the Bible, all the more so in Shas. Usually it takes the form of wordplay and double entrendres, however. Examples I have personally noted would include the phrase רגלים לדבר in Sanhederin 78a, used in connection with והתהלך בחוץ על משענתו; the expression רחילא בתר רחילא used in connection with R. Akiva’s wife; the question וכי חולדה נביאה היא in the first chapter of Pesachim; the phrase מראית עין in connection with eye diseases used in Bechoros 44a; and more.

The examples you cite, however, seem more examples of what later generations see as (bitter) irony, not actual humor. The statement made about R. Ammi comes in the middle of a slew of hyperbolic numbers, including the number 70, and the possibility of referencing תורה צוה was quite clearly made seriously. As for תלמידי חכמים מרבים שלום – this only appears funny, or ironic, to those who don’t understand where Shalom comes from. Peace comes from a multiplicity of opinions, where everyone is free to express his belief without fear or recrimination. The sages, as evidenced by their frequent arguments, gave us a wonderful model of freewheeling debate. In today’s Orwellian dystopia, as noted above by multiple commenters, true debate is rapidly disappearing. That’s not שלום, that’s enforced groupthink.

Did the Netziv’s second wife live (and die) in Israel?

“do even feminists wish to claim that killing comes as easy to women as to men? Do they really want to be “equal” with men in this matter?”

Ah, Professor. This is One Of Those Things that in Current Year it’s OK for some people to say but not others. Feminists are perfectly allowed to say that women have some special insights or a more peaceful orientation or whatever. (And, of course, that men and women have different minds is a fundamental of trans ideology.) But for a man to suggest that men and women have different minds or the like is a Thoughtcrime.

Marc – In the past you mentioned other sources as well that allude to non-Jews keeping Shabbos:

“Ibn Ezra, Ex. 13:7, 20:8, Lev. 17:13-14, 20:25, states that a non-Jew living in the Land of Israel (i.e., a ger toshav) is obligated to observe Shabbat. He is also not to work on Yom Kippur, to refrain from eating hametz on Passover, and to only eat kosher food. This is Ibn Ezra’s understanding of the peshat of the Torah, but the Talmud records no such laws.The most significant of the sources I can cite, and the one closest to the Gaon’s position, is found in Avodah Zarah 64b. Here the Talmud quotes אחרים as saying that a ger toshav has to observe all the mitzvot with the exception of ritually slaughtered meat. The Hazon Ish, Yoreh Deah 65:6 wonders about this position, since does it mean that a non-Jew must wear tefillin and eat in a sukkah? He assumes that the talmudic passage means that non-Jews in the Land of Israel are only obligated in the negative commandments, and this is required so that Jews not be negatively influenced by their non-Jewish neighbors. See also R. Asher Weiss, Minhat Asher, Bereishit, p. 19.”

(THE VILNA GAON, PART 3 (REVIEW OF ELIYAHU STERN, THE GENIUS) BY MARC B. SHAPIRO

February 23, 2014 )

No one is disputing that in the Tannaic and Amoraic periods monogamy was the default. (I don’t think you even need your claim about two instances. The monogamy assumption was actually strong enough that it had halachic force.)

What’s being challenged is your assumption that it was common in earlier periods. The point is that the earlier periods focused on kings and others in that small subgroup where polygamy was common, so having many such instances doesn’t prove anything at all.

And again, the fact that the patriarchs only entered polygamous marriages for specific reasons suggests that it was not the default, even at that time.

Re woman and men – it probably should have been noted that these same attitudes to women can be found among gentile writers throughout the centuries, too numerous to cite. And it should further be noted that while most likely there has been some genuine evolution of thinking in this area, you would not be able to know this conclusively, as it is illegal (everywhere de facto, some place de jure) to say otherwise. You know very well, Dr. Shapiro, that freedom of intellectual thought has long been dead in Academia. So, who knows what people really believe.

Of course, whatever has been said in books – and as you note, there have been a whole range of opinions – none of it ever bore any relevance to how things played out in practice.

2. Avi appears as a female name, and in Tanach and Shas the names Bracha, Ahava, and Chaviva appear as male names. R.C. Kaneveky has a list of such names in טעמא דקרא regarding לא ילבשץ

3. The use of the unusual phrase פרא אדם is probably meant etiologically, to explain why the Bnei Ishmael lived in פארן. It is meant to parallel the description of Esav as an איש שעיר to explain etiologically when he lived in הר שעיר. The two go together, as indicated in the verse וזרח משעיר למו הופיע מהר פארן. (I made this suggestion, which I believe אמת, in an article in JBQ)

4. Re Multiple Wives, the issue comes up in connection with the מאן הוי ליומא passage in Yoma and Yevamos. RR Margolios goes to great lengths to show it was never common, at any time in history. Others distinguish between Israel (under Roman rule) and Bavel, where it was more common than E. Israel, but still not actually common.

Regarding names that seem to have changed gender: There is a relatively modern trend to take male names (Gavriel, Yosef etc.) and add “ah” to the end to make them feminine (Gavriella, Yosefa, etc). There is one instance in Tanach where the opposite is true – in Divrei HaYamim I 4:36 there is a list of what appears to be sons, including “Yaakovah”, which is a man, and today would be considered a female name.

ואין צורך להרבות דברים על הזרות שבדבר: מה איכפת למי אם שבת או לא שבת, ומה היא הראיה מאותו פסוק, המוסב על קיץ וחורף וכו’, ומה ענינו לכאן ולעכו”ם דוקא?

This s a very unfortunate misunderstanding, and example of someone who is unfamiliar with the unique language of Aggadeta.

The verse in Noach is describing the existential state of of life for a non-Jew, an unceasing seasonal cycle of work , encompassing a physical and material existence. This is their life. Hence, גוי ששבת חייב מיתה, the spiritual element of Shabbos is for them akin to death. Indeed, even today, those with no connection to Torah values look askance at Sabbath observance, and view it as imprisonment – a day where all their cherished life activities are prohibited.

THere’s an explicit example of humor cited in the Talmud BK 17b.

“הוה קמהדר ליה בבדיחותא וא”ל אנא שנאי חדא ואת שני חדא”

[This always stuck in my head because it matched a famous line from Chaim Soloveitchik (the BR’s mentally ill son).]

What is the famous line from Chaim Der Rav’s that you are referring to?

He once had a pshat in Yaakov saying ונתן לי לחם לאכל ובגד ללבש. What’s a בגד ללבש? You can wear any בגד. Brisker תירץ: if you have a cloth which is 3 tefachim, it has a din beged, but you can’t do anything at all with it. So Yaakov requested a בגד ללבש – one that you could wear.

So a guy asked him, OK, but then what do you do with לחם לאכל? So he responded:

“דאס האט נישט מיט מיין ווארט. איך האב א פשט אין בגד ללבוש. אז דו האסט א פשט אין לחם לאכל קענסט דו זאגען …”

Ha, that is hilarious.

Lechem Le’echol could be le’afukei from lechem that’s no longer rauy leachila. Unless then the shem lechem is paka?

“…reality cannot see that men are naturally more inclined to violence than women.”

So now at least you broadcast subtly your socio-political persuasion in case anyone missed it hitherto

Get out of your sociological politically and emotionally correct crowd once in awhile

Societies as they become more feminized have decayed quite quickly

would you wish for the IDF to become more feminized

Even Madeleine Albright acknowledged that societies dominated by women do not turn Better

Regarding “fi”‘, N. Wieder has a brilliant article about it (also published in his collected articles)

Regarding dagesh and the Sephardim, see what R. BZ Kohen, a talmid of R. Mazuz, wrote in his sefer- S’fat Emet

I think the author is misunderstanding the comparison of the Shabbat Shel Mi.

Although the comment could be construed as a joke about women, it seems more likely that the comparison is between the very similar categories of laws discussed in the two chapters.

Both chapters are uniquely about whether the laws of carrying on Shabbos apply to wearing various kinds of items: the fifth chapter is about what animals might “wear” (bridles, collars, saddles, bells, etc.), and the sixth chapter is about what humans might wear (with some examples that tend to be specific to men – such as phylacteries, other examples that tend to be specific to women – such as various kinds of feminine jewelry, and plenty of examples that tend to apply equally to both men and women).

The comparison is most likely not between women and animals at all, it just so happens that the chapters are named after their first words. The Shabbat Shel Mi is comparing the chapters which he refers to by their titles (“With What May an Animal [go out]…” and “With What May a Woman [go out]…”, respectively). The zarzir bird and the crow that flock together are the two similar categories of laws whose chapters are juxtaposed in this tractate.

“Yeshayahu Leibowitz quipped that the Sages must have had a good sense of humor, since they included the following text in the Talmud : תלמידי חכמים מרבים שלום בעולם.”

In one of his final inspiring lectures before this Elul, excerpted below, R. Jonathan Sacks recalled discussing this Gemara with R. Norman Lamm. See link to video and transcript, consisting of three mini-lectures , “Faith & Insecurity” , “Rethinking Failure”, “Building the Future”(quote is from “Building the Future”):

https://rabbisacks.org/elul5780/

“But on one occasion he said to me, “Jonathan, you know, there’s only one joke in the Mishnah.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Well, talmidei chachamim marbim shalom b’olam, rabbis increase peace in the world.” He said, “That has to be a joke, right? The more rabbis, the more rows, that must be a joke.”

I said, “Rabbi Lamm, if I may suggest, it isn’t actually a joke. But to understand it,

you have to go to the end of the sentence. It says, marbim shalom b’olam shene’emar, as it is said, v’chol bonaich limudei Hashem v’rav shalom bonaich, the verse from Isiah, all your children should be learned of the Lord and great shall be the peace of your children, al tikrah banaich, don’t read it your children, elah bonaich, call it your builders.” I said, “If rabbis are children, they do not increase peace in the world. But if they are builders, they do.” And the proof is Moshe Rabbenue because when he got the Israelites to build the Mishcon, there was no argument between them, absolutely none. There was perfect peace. Why? Because they were building. Rabbi Lamm was supremely a builder…”

R. Sacks then concludes with a post-COVID message:

“I have to say that is our challenge in the coming year, so much has been lost, so much has been destroyed. We have to become builders. We have to build that future. Then we can go back and think about the past, but not now, not yet. That is not the tzav hasha’ah, the command of our time. First, let us build that future. Let us repair everything that has been damaged. Let us build something even more beautiful in place of that which has been lost. May Hashem give us the strength to build, and in that building may we find peace. Shana tova”

It is worth adding that despite Rashi to Menochos 43b, Avraham Grossman (in Chasidos U’mor’dos, Magnes) spends a few pages making a case for Rashi’s sensitivity towards issues of female equality in his particular choice of midroshim that seemingly promote equality and overall rejection of the many b’reishis midroshim with a maidservant-master paradigm. E.g.( in another piece, not that book -I forget where) Grossman cites the verse B’reishis 3:16 “v’el ishaikh t’shuqosaikh, v’hu yimshol bokh”) where rashi very narrowly constrains that whole yimshol stuff to only the matter of the male taking sexual initiative in matrimonial matters.

Oops. I did that citation from memory – incorrectly. The volume Chasidos U’mor’dos I mentioned above was a Mercaz Zalman Shazar pub (2003), not Magnes.

There are many cases where the word גבר does not mean specifically the male sex, like the word “man” in English. The גמרא in זבחים is not anomalous at all. Look throughout the Talmudim and Targumim, דוק ותשכח.

Hi, I desire to subscribe for this blog to take latest

updates, thus where can i do it please help out.

Fascinating post! Thanks Marc

I am glad that Mechi Frenkel quoted the passages from Grossman where he pretty convincingly posits for Rashi’s sensitivity towards the status of women.

It is a pity he doesn’t deal with the Rashi on Menachos 43B. However, I would make the following suggestion. It isn’t Rashi that equates a woman with an Eved but it is the obvious meaning of the Talmud. Possibly this bothered Rashi to the extent that he then “Reinterprets” the statement of the Talmud with his forced 2nd explanation. You can see how hard Rashi is trying in the follow on Rashi at the top of 44a where he really struggles to then explain “zil tephay” according to his 2nd explanation.

See also the two explanations offered by Rashi on Pesachim 108a as to why women don’t lean.

There is a fascinating but controversial Torah Temima on Beraishis 24:1 (6) that suggests that R’ Meir, who authored the Berocho “Shelo Asani Isha”, might have had a negative view of women due to two difficult experiences.

The reference to Grossman that I am aware of is in his fabulous book “Rashi” published by Littman, pages 267-286. On page 241 he discusses Genesis 3:16

With actually thousands of sportsbook options to pick out from,

it can be daunting.

Add the relative pick command to build a hyperlink between the player name, and their group

name.

I read this piece of writing fully on the topic of the resemblance of most up-to-date and preceding technologies, it’s awesome article.

Let’s say there is a tennis match among Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal

for the Australian Open championship, and Nadal is slightly favored.

Wonderful items from you, man. I’ve remember your

stuff previous to and you are simply too wonderful. I actually like what you’ve obtained right here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which by

which you assert it. You are making it enjoyable and you continue to take

care of to stay it sensible. I can not wait to read far more from you.

That is actually a wonderful site.

After I originally commented I seem to have clicked the -Notify me

when new comments are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is

added I receive four emails with the exact same comment.

There has to be an easy method you are able to remove

me from that service? Appreciate it!

It’s truly very difficult in this full of activity life to listen news on Television, so I just use internet for that reason, and take the hottest news.

After checking out a number of the blog posts on your blog, I

really like your way of writing a blog. I saved as a favorite it to

my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back in the near future.

Please check out my web site as well and let me know your opinion.

Appreciation to my father who shared with me on the topic of

this blog, this webpage is genuinely awesome.

Regarding the link between תורת אמך and food, see the explanation proposed by R. Fishman-Maimon in the introduction to the Second Kuzari, p.13.

If you do choose to quit your job, “you have to have one thing that has meaning that fills your time,” Bradlry says.

Feell free to suirf to my web page; 파워볼분석기

In the quotation from Kimhi, ימשוך should be ימשול

The trouble with Meisels’ theory about the astrolater who keeps sabbath is that all the mss and the early editions of the Talmud say גוי ששבת rather than עובד כוכבים ששבת in the dictum of Shimon ben Lakish.

On the dehumanization of women, the worst offenders are authorities who deny women the divine image which makes humans special – חביב אדם שנברא בצלם – and makes murder different from mere killing – שפך דם האדם. Among the rabbis these include Jacob Anatoli and Isaac Abarbanel – see discussion https://tora-forum.co.il/threads/%D7%91%D7%A6%D7%9C%D7%9D-%D7%90-%D7%91%D7%A8%D7%90-%D7%90%D7%AA%D7%95-%D7%96%D7%9B%D7%A8-%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%A7%D7%91%D7%94-%D7%91%D7%A8%D7%90-%D7%90%D7%AA%D7%9D.22941/