Rambam The Poet?

Rambam The Poet?

Ovadya Hoffman

Most readers are familiar with the general character and productivity of Maimonides, I will therefore keep the preamble to a minimum. The indelible legacy left by Maimonides is that of a legalist and thinker, not of a poet or a preacher. That’s not to say that Maimonides lacked the poetic skill. In fact, even from his purely legal works one can detect his elegant tongue and imaginative faculties, never mind the many missives, introductions and intermittent non-legal material included in his Code which exhibit overt tones of a skillful mouthpiece characterized by his eloquent and passionate appeals, charming metaphors and moving rhetoric.[1] And yet, not much –if any- of his authentic, complete pieces of poetry survived.[2]

One poem ascribed to Maimonides was composed in Arabic depicting the story of Purim. Recently, a dear friend, Jacob Djmal of The Jewish Bookery, showed me a book containing this poem declaring it to be of Maimonidean authorship. I will use this source as my point of departure.

R. Yosef Shabbtai Farhi published a book titled Nora Tehilot in Livorno 1864.[3] On the title page the author states he has translated the book of Esther into colloquial Arabic (“ולכן נתתי אל לבי… להעתיקה בלשון ערבי”) and included a piyyut in Arabic authored, so he claims, by Maimonides (“ונפך שפי’ר[4] פיוט בל’ צח ערבי מהרמב”ם ז”ל יפה אף נעים”). However, Farhi provides no information as to the piyyut’s provenance. One wouldn’t be afoul to suspect that, regardless of the piyuut’s origin, its attribution to Maimonides could easily garner sales. Who would pass up a book containing a rare glimpse of the great Maimonides’ poetic creativity? Again later on (31a) the author titles the aforementioned piyyut “בלשון ערבי מהרמב”ם ז”ל מיוסד על פי מאמרי רז”ל על סדר א”ב… לחן אימפיסאר קירו קונטאר”. So what are we to make of this piyyut? Where did Farhi get it from?

A manuscript housed at the Ben Zvi institute (MS. 1327), dating from a year before Farhi’s book was published, is a handwritten copy of what alleges to be an Arabic translation of Esther authored by Maimonides (“ספר מג'[ילת] אס'[תר] מלערבי הנקרא שרח אל מגלה להר’ משה בר מימון זלה”ה”).[5] At the end of the manuscript (beginning on p. 76) the same piyyut which appears in Farhi’s book is produced here except it lacks any attribution.[6] It could be fair to assume that the copyist only naturally considered the piyyut to be of the same authorship as the translation, Maimonides, although he didn’t state as much. He may have chosen to include it in the manuscript on the belief that it was from Maimonides or he may have harbored doubts as to its authenticity and therefore left it unattributed. In any case, where did this copyist get it from?

Another book titled “פירוש מגלת אסתר בלשון ערבי הנקרא שרח אל מגלה להנשר הגדול ארך הכנפים ורב הנוצה הרמב”ם ז”ל” was published in Livorno 1759 at the behest of Abraham b. Daniel Lombroso.[7] At the end of the first paragraph (2a) it reads: “ואל שרח משחר אליה מלקוטין מן כלאם רבותינו ז”ל ואל תלמודיין אל בבלי ואל ירושלמי” (loosely translated: a translation based on an anthology of both Talmuds). At the conclusion of the translation a number of piyyutim by various authors are produced. One of those piyyutim are evidently of anonymous authorship and simply titled “פיוט בלשון ערבי מיוסד על פי מאמרי רז”ל לחן אינפיסר קיירו אקונטאר” (p. 46a).

With no older documentation of this piyyut, I can only guess that one -possibly Farhi himself- hastily assumed an Arabic poem, appended to an Arabic translation authored, allegedly, by Maimonides belonged to him as well and consequently formalized the attribution.

Addendum

In 1845 Michael Sachs wrote that he was skeptical about Maimonides’ involvement and authorship of poetry.[8] About a year later, in a letter to Sachs upon receiving his book, Samuel D. Luzzatto argued with one of Sachs’ points regarding a particular piyyut ascribed to Maimonides and then marshaled evidence from R. Shimon b. Tsemaḥ (Duran) in his Magen Avot p. 84[a] where it is evident that Maimonides wrote two other piyyutim. However, Luzzatto added, the word “הרמב“ן” in Magen Avot is a printing error and should read “הרמב“ם”; [9] more on this below. Years later, in 1854, Shneur (Senior) Sachs repeated the notion of Maimonides’ aversion to composing poetry and maintained that all which we have from him is a single piyyut.[10] Eliezer Landshuth further attempted to set the record and addressed the later Sachs in his book, quoting Shadal and his emendation to the text of the Magen Avot.[11] I won’t go on to list a record of all the authors who followed suit in quoting the Magen Avot as a source for Maimonides’ authorship of a couple other piyyutim and will suffice to say that as late as the early 1900s Meir S. Geshuri asserted the same claim[12] and he was likewise cited by the celebrated Hayyim Schirmann.[13]

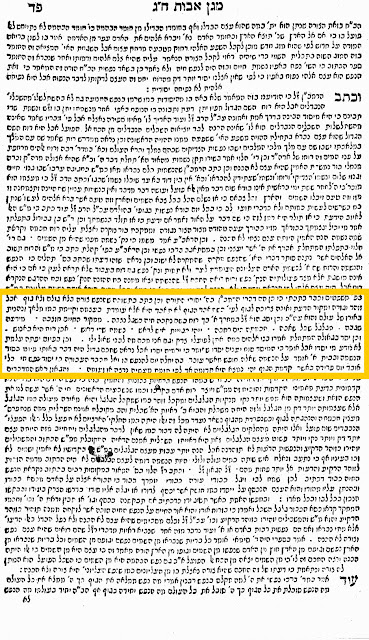

The Magen Avot was first published in Livorno 1785. Here[14] is the page:

Alternatively, here is the text:

כבר כתבתי כי הן הם דברי הרמב”ן בה’ יסודי התורה וכן כתב בתשובה שהנפש צורה בלא גולם ולא גוף אבל זוהר וגזרה ומקור הדעת ואינה צריכה לגוף לפי’ … אבד הגוף לא תאבד היא אלא עומדת בעצמה וקיימת כמו מלאך ונהנית באורו של עולם והוא עה”ב וכן יסג הוא ז”ל במחרך א’ בך רוח בשם נקבה חיה כשגל נצבה. ממקור החיים חוצבה. מידעה שגבה. מגלגל שכל שאבה. חכמתה כים רחבה. ייהי הגיית איש לראש. נשמה שרי דרוש. אכן רוח היא באנוש. וכן יסד בגאולה המתחלת אמרו בני אלהים כמה אתן לפועלי צדק וגם אני מכם מה לבני שאול ולי. וכן בפיוט יפתה עלמת לא נודע מי יסדו אבל אומר כי המיסד סוח יענים יסדו שאומר כי ירמיה יסדו אכל נראה שחכם גדול היה דבר באותו פיוט בסוד הנשמה ובבית א’ אומר על הנשמה שאלה חופש מאשר עובר בה יחלה יום להנפש בו ואל תכבד העבודה כי יסוד נפש חי כלי אובד יום פרידה כאשר קדמת הגוף יהי נמצא הוא קדומה אך לפי תומת מעשיה נרצה או זעומה

Besides for the unintelligible sentences and typos, the most glaring error is, as Shadal and others called attention to, the printing error of רמב”ן instead of רמב”ם. Now, if that’s all one corrects it is now conceivable that Duran ascribed to Maimonides the piyyutim which he mentioned. Somewhat surprising, or not, is that the same errors appear exactly so in the newer edition of Magen Avot published by Mechon HaKtav in Jerusalem 2007, despite the publisher’s claim of it being critically edited.[15]

Of the different manuscripts I consulted in determining the original text only one had a different and coherent read. This manuscript is estimated to be from 15th-16th century and is housed in The Royal Danish Library.[16] In order to grasp the flow of the material it is necessary to include the preceding paragraph (in the image above, it begins four lines above the yellow box). Following, is my transcription of the manuscript:

וכן החכם ר׳ אברהם ז״ל כתב בפי׳ קהלת כי מה שאמ׳ והרוח תשוב אל האלהים אשר נתנה סותר דברי האומרים שהנפש מקרה שהמקרה לא ישוב וכן נראה שזה הוא דעתו כי כתב בפי׳ תלים כי הנפש והנשמה והרוח שם אחד לנשמת האדם העליונה העומדת לעד ולא תמות ונקראה נפש גם רוח בעבור שלא תראה לעין כי אם אלה וכן כת׳ בפרש׳ כי תשא ובכל מקום קורא אותה נשמה עליונה כמו שכתב בפרש׳ ואלה המשפטים ר״ל כי היא אינה מושגת אלא מצד פעולותיה הנקראים נפש ורוח רואה החכם ז״ל כי הנשמה יצאו ממנה כח ההזנה הנקרא נפש וכח ההרגש הנקרא רוח אבל הוא עצם אלהי לפי הנראה מדעתו ולא הכנה לבד. וכן יסד הוא ז״ל במחרך אחד בך רוח בשם נקבה חיה כשגל נצבה ממקור אור יוקבה מצור החיים חוצבה מי דעה אותה שגבה מגלגל שכל שאבה חכמתו היא רחבה ויהי בגויית איש לראש נשמה שדי דרוש וכן רוח היא באנוש. וכן יסד בגאולה המתחלת אמרו בני אלהים במה אתן לפועלי צדק וגם אני מכם מה לבני שאול ולי. וכבר כתבתי כי כן הם דברי הר״ם במז״ל בהלכות יסודי התורה. וכן כתב בתשובה שהנפש צורה בלא גולם ולא גוף אבל טהר וגזרה ומקור הדעת ואינה צריכה לגוף לפי׳ כשיאבד הגוף לא תאבד היא אלא עומדת בעצמה וקיימת כמו מלאך ונהנית באורו של עולם והוא עולם הבא וכן בפיוט יפתה עלמת לא נודע מי יסדה אבל אומרי׳ כי המיסד סורו יענים יסדו אשר אומרים כי ירמיה הנביא יסדו אבל נראה שחכם גדול היה דבר באותו פיוט בסוד הנשמה ובבית אחד אומר׳ על הנשמה שאלה חופש מאשר עובד בה יחידה יום להנפש בו ואל תכבד העבודה כי יסוד נפש חי בלי׳ אובד יום פרידה באשר קדמת גוף יהי נמצא היא קדומה אך לפי תומת מעשים נרצה או זעומה

As observed by others, we see that the correct reading is רמב”ם instead of רמב”ן. But most significantly, we see that some lines from Duran’s discussion of Abraham ibn Ezra’s view [regarding the nature of the soul] were transposed to after the mention of Maimonides, giving the impression that “וכן יסד הוא ז”ל” and “וכן יסד” refers to Maimonides, thereby leading scholars to believe that Duran attributed these piyyutim to Maimonides. Indeed the quoted muḥarrakh[17] “בך רוח” and the geulah[18] “אמרו בני אלהים” are both compositions of ibn Ezra.[19] In conclusion, the basal support, which for years scholars have pointed to for evidence of Maimonides’ rôle as a poet, is negated.

At this point we should make mention of the last piyyut which Duran notes that “some say Jeremiah authored, nevertheless it’s apparent a great sage spoke it”. This piyyut, also of the muḥarrakh genre, has since been identified as being authored by R. Joseph ibn Zaddik (11-12th century) and subsequently published in a collection of his piyyutim.[20]

As I attempted to have this brief essay completed in time for Purim I lay here the pen and hope to return to a discussion of a perplexing and elusive piece quoted by Duran.

[1] See, however, Isadore Twersky, Introdution to the Code of Maimonides (New Haven & London 1980), 250 fn. 29.

[2] Cf. Hayyim Schirmann, Toldot HaShirah Ha’Ivrit BeSfarad HaNotsrit Ubederom Tsarfat (Jerusalem 1997), 280 fn. 6 for bibliographical references. See also addendum below.

[3] https://hebrewbooks.org/34131

[4] A play-on-words of Ex. 28:11 “והטור השני נפך ספיר”; with ‘שפיר’ meaning ‘good, fine’.

[5] See the journal Sarid U’palit (R. Yaakov Moshe Toledano, Tel Aviv n.d.), i p. 65 and Perush Megilat Esther LeHanesher HaGadol Rabbenu HaRambam (trans. Yosef Yoel Rivlin, Jerusalem 1952 [in a note to the latter’s preface 1943 is given as the publication year for Toledano]). Toledano believed this to be an original translation by Maimonides and only alluded to anonymous gainsayers. See however Hartwig Hirschfeld’s critical analysis of the translation in his essay Notiz uber einen dem Maimuni untergeschobenen arabischen Commentar zu Esther (Semitic Studies in Memory of Rev. Dr. Alexander Kohut, Berlin 1897) 248ff. Per Toledano’s dismissal of the translation belonging to Rabbi Maimon, Maimonides’ father, on account of a quote not found in the respective translation, cf. Tiferet Yisrael (R. Shlomo b. Tsemaḥ Duran, Venice c. 1600) 118b, quoting an Arabic translation, which according to his father, was authored by Rabbi Maimon.

[6] https://www.nli.org.il/en/manuscripts/NNL_YBZ000115506/NLI#$FL31920894

[7] https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001773455/NLI . Cf. above, fn. 5.

[8] Die religiöse Poesie der Juden in Spanien (Berlin 1845), 204.

[9] Ozar Nechmad (Vienna 1857), vol. 8 p. 27. Shadal’s letter is dated 26 Kislev 1846. Leopold Zunz likewise suggested the correction, Literaturgeschichte der synagogalen Poesie (Berlin 1865), 478.

[10] Kerem Hemed (Berlin 1854), viii p. 30.

[11] Amude Ha-Aboda (Berlin 1857), 230.

[12] Rabbenu Moshe ben Maimon, ed. J.L. Fischman (Tel Aviv 1935), 289.

[13] Toldot HaShirah Ha’Ivrit BeSfarad HaNotsrit Ubederom Tsarfat (Jer. 1997), 281 fn. 9; see also Yosef Tobi in Ben ‘Ever La’arav (Tel Aviv 2014), vii 83 fn. 148. Regarding the halachic texts of Maimonides and the Geonim which Tobi cites to demonstrate Maimonides’ assailment of poetry, cf. Boaz Cohen’s Law and Tradition in Judaism (New York 1959), 167ff.

[14] https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=9446&st=&pgnum=171&hilite=

[15] https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=39932&st=&pgnum=552

[16] http://www5.kb.dk/manus/judsam/2009/sep/dsh/object21822/en/#kbOSD-0=page:174

[17] Arabic for ‘mover’; alternatively, ‘prompter’. Of Spanish style, and often employed by ibn Ezra, the muḥarrakh was usually recited before a reshut for Nishmat Kol Ḥai. On the reason for the given name, cf. Ezra Fleischer’s Shirat Hakodesh Ha’ivrit Beyeme Habenaim (Jerusalem 1975) 399-400, Leon J. Weinberger’s Jewish Hymnography (London & Oregon 1998) 436, Peter Cole’s The Dream of the Poem (Princeton University Press 2007) 537 and an original theory suggested by Ephraim Hazan in Tarbiz (Jerusalem 1977) xlvi 323.

[18] The concluding piece of a Yotser sequence.

[19] The former was published in toto in Jacob Egers’ Diwan LeRabbi Avraham ibn Ezra (Berlin 1886), 21 fn. 67 [beginning “אל מתנשא על כל לראש”], but confused, and thence omitted, by Israel Davidson in Otsar HaShirah VeHapiyyut (New York 1970), i n. 3854 with another “אל מתנשא” incorrectly supplying Egers as a source. Davidson’s reference to David Rosin’s Reime und Gedichte des Abraham ibn Esra (Breslau 1887) “ב 16”, does not yield our piyyut and appears to be incorrect. The latter was published, most recently, in Avraham ibn Ezra – Shirim, ed. Israel Levin (University Tel Aviv 2011), 191; here and other editions have “במה אתן לפועלי חסד ואם אני…” unlike Magen Avot. Cf. Egers, ibid., 165 n. 198; translated into English in Leon J. Weinberger’s Twilight of a Golden Age (University of Alabama Press 1997), 246ff.

[20] Yonah David, Shire Yosef ibn Zaddik (Israel 1982), 55 and elegantly translated into English by Peter Cole, ibid., 139.

3 thoughts on “Rambam The Poet?”

It’s highly unlikely that the poem was written by the Rambam, or that the Rambam wrote much poetry at all, for the following reasons:

The Rambam is known to have not been a fan of piyutim. There are a number of sources in the Rambam’s writing for this – see for example Moreh Nevuchim, Pt. 1, Ch. 59, and R. Y. Kafach’s note 47 in that chapter.

Virtually all of the Rambam’s corpus is well known, and was continuously known through the ages from Rambam’s time through today, and studied extensively, both his halachic works in yeshivot, and if I recall correctly also Moreh Nevuchim for several centuries in jewish schools of philosophy in Spain and France in approximately the 13th through 15th centuries. There are extensive discussions of and references to the Rambam’s works throughout the centuries, yet no mention or citation of any poetry. It stands to reason that had the Rambam written any poetry we would likely have copies of it today, or at a minimum see it cited in some historical work.

The Rambam himself cross-references and mentions his works occasionally, yet never mentions any poetry.

Many of the Rambam’s works were found in the Cairo Geniza, including hand written works by the Rambam himself, yet no poetry of the Rambam was found.

Based on the above we can be quite confident that poetry attributed to the Rambam that first came to public light in 1864 was was virtually certainly not written by the Rambam, and that it’s unlikely that the Rambam wrote any significant poetry.

I find the mishna torah “poetic” in spots (e.g. hilchot tshuva)

KT

Rabbi S. Sassoon in מחקר מקיף על כתב ידו של הרמב”ם cites the fact that the Rambam composed introductory poems to his Pirush Hamishna, the More Nebukhim and the Mishne Torah, and even provides the text to the poem that introduces the Pirush Hamishna found in one of the extant manuscripts.