An enigmatic Pseudo-Shklov edition of Barukh She’amar

An enigmatic Pseudo-Shklov edition of Barukh She’amar[1]

By Marvin J. Heller

A title-page describing the work as an 1820 Shklov press publication is indicative of an enigmatic pseudo-edition of Baruch She’amar, a halakhot work pertaining to Sefer Torah, tefillin, and mezuzot by R. Simeon bar Eliʻezer (d. c. 1360). The author of Barukh She’amar, R. Simeon bar Eliʻezer (d. c. 1360), was born in Saxony, Germany and died in Eretz Israel. Orphaned at the age of eight, Simeon was adopted and raised by R. Issachar, a scribe who taught Simeon his craftsmanship, at which Shimon developed such expertise that R. Solomon ben Jehiel Luria (Maharshal, c. 1510-1574) referred to Simeon as “the head of all scribes.”[2]

There is confusion as to the actual dates and places of printing of this imprint. The title-page clearly gives Shklov as the place of printing and dates it with the chronogram “[We must] teach the children of Judah the archer’s bow קסת [קשת] ללמד בני יהודה (580 = 1820)” (II Samuel 1:18). However, to get the date 1820 the shin ש (300) in the verse has been replaced with a sameh ס (60) for the total of 580 = 1820. Nevertheless, bibliographic sources are in agreement that the publication place of the 1820 Barukh She’amar was Minkowce (Minkovtsy), a village in Podolia near Belarus in north-eastern Poland. However, there were earlier editions of Baruch She’amar issued in Dubno in 1796 and again in Shklov in 1804.

The two presses noted in conjunction with the printing of the subject editions of Baruch She-Amar are in Shklov and Minkowce (Minkovtsy). The former location, Shklov, is in the Mogilev region of Belaurus on the Dnieper river, approximately 410 km. from Vilna. It was home to a Jewish community dating to the late seventeenth century. A charter permitting Jewish settlement in Shklov was first received in 1668. Not long after, according to a visiting diplomat in 1699, Jews were “the richest and most influential class of people in the city.” By 1776 the Jewish population of Shkolov was 1,367. Shklov was an intellectual center as well as being an important commercial center in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[3] Hebrew presses in Shklov date to the late eighteenth century and as many as 226 Hebrew titles are attributed to that location until 1835. Minkowce, in contrast, is in the Kamenets-Podolski district of the Ukraine. A smaller community, its Jewish population in 1765 was 375. A Hebrew press was active there from 1795 to 1812, publishing almost forty titles.[4]

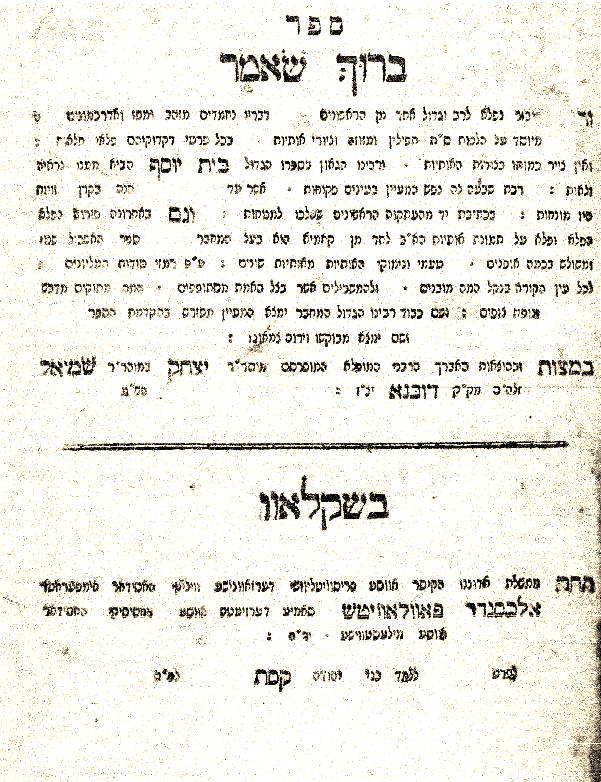

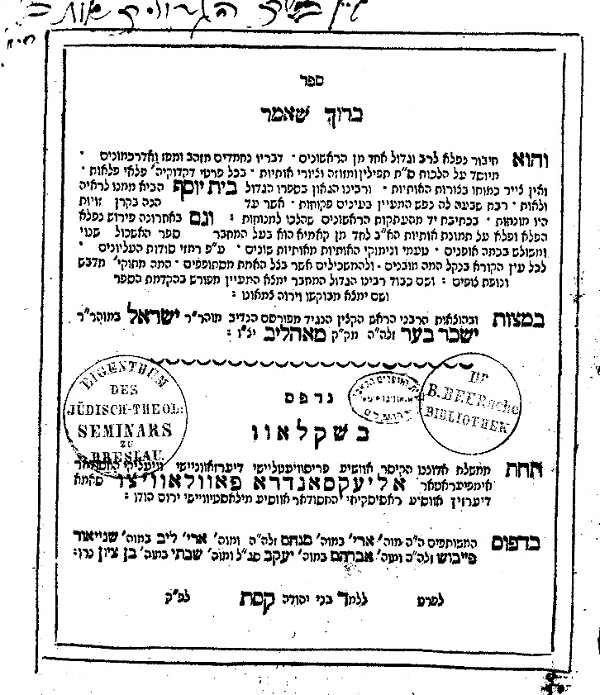

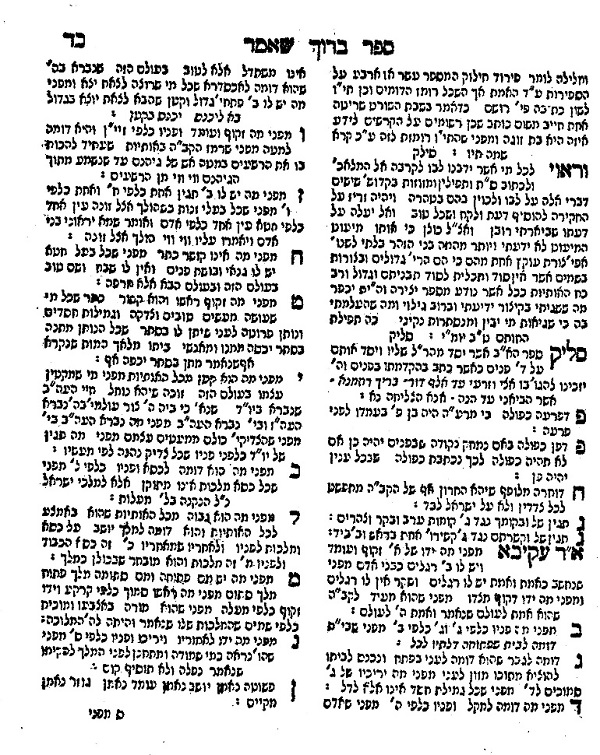

1804, Baruch She’amar, Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

1820, Baruch She’amar, Courtesy of Virtual Judaica

Entries in bibliographic works for Baruch She’amar consistently question the title-page of the 1820 edition’s place of publication when recording this work. Ch. B. Friedberg, in the Bet Eked Sefarim, records several editions of Baruch She’amar, among them [Minkowce 1795], Shklov 1804, and [Minkowce 1820]. In his Hebrew typography in Poland Friedberg records Baruch She’amar under Minkowce, 1796 and 1820 and under Shklov the 1804 edition of that work, dated קסת ללמד בני יהודה (564 = 1804). Vinograd, in the Thesaurus, lists a 1795 edition of Baruch She’amar referencing Friedberg, noting that it is questionable and an 1820 edition in which the title-page states Shklov, and in the entry for that work under the latter location has 1804 and 1820 entries, and for the 1820 edition referring the reader to Minkowce. Apart from these editions there was, as noted above, a prior 1796 Dubno imprint as well as several later editions.[5]

The text and format of the 1804 and 1820 editions are alike, both quartos (40: 32 ff.) and the title-pages of the two editions of Baruch She’amar even employ the same chronogram, modified to reflect the date of publication. Both title-pages credit R. Israel ben Issachar Ber from Ohilov for bringing the book to press, apparently the latter a repetition from the earlier printing. However, the 1804 Baruch She’amar names the printers as Aryeh ben Menahem, Aryeh Leib ben Schneer Feibush, Abraham ben Jacob, and Shabbetai ben Ziyyon as the printers. In contrast, the 1820 edition does not name the printer.

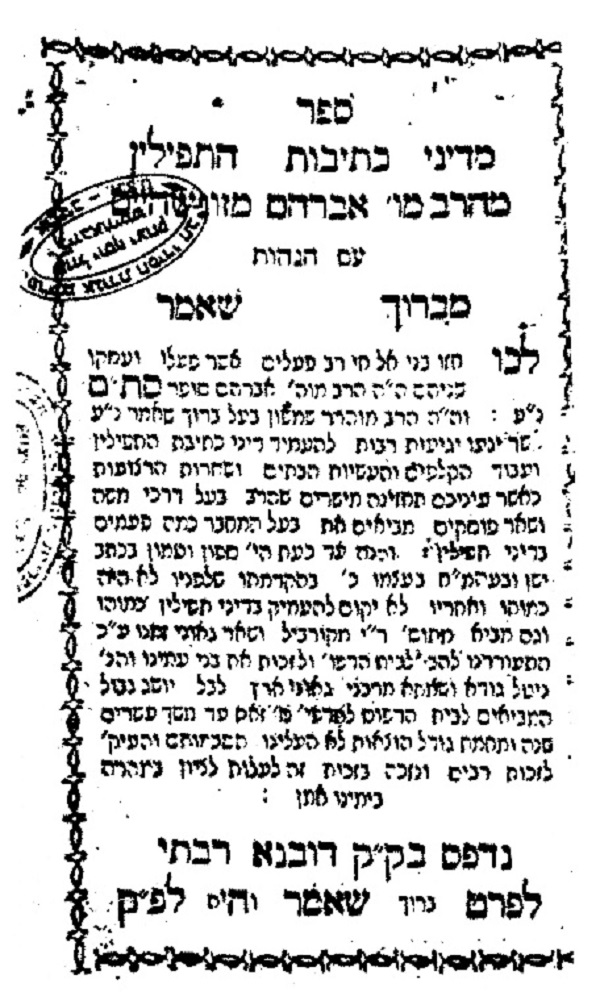

Abraham Yaari has entries for both Shklov and Minkowce in his bibliographical articles on those locations. In his article on Shklov he writes that a partial edition of Baruch She’amar had been printed previously in Dubno in 1796 and this, the 1804 edition, was the first complete printing of that work. He adds that Friedberg’s entries are in error and that the 1820 [Shklov] edition does not exist. Concerning the 1820 Minkowce edition, Yaari informs that there is an approbation from R. Judah Leib ben Zevi ha-Kohen Av Bet Din in Minkowce dated 11 Kislev 1820 (November 29, 1819) who refers to the earlier Minkowce printing and states that it is now being reprinted here, that is, in Minkowce. Yaari again takes issue with Friedberg, concluding “in truth, a complete edition was first printed in Shklov in 1804 (and based on that edition it was printed in Minkowce in 1820). A partial edition was printed in Dubno in 1796 and perhaps this is the reason for the errors.”[6]

1796, Barukh She’amar, Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

While Yaari does appear to accurately summarize these editions he does not explain why the title-page of the 1820 Baruch She’amar clearly states Shklov as the place of printing rather than Minkowce. It is well known that in several instances the place of printing and the publication dates were modified to mislead the censor. However, that is not the case with other titles printed in both of our locations and the subject matter of Baruch She’amar on the halakhot pertaining to scribal arts is not one likely to attract the censor’s attention.

The printers of the 1820 edition removed the names of the printers from the 1804 title-page; it seems highly unlikely that they would have omitted correcting the publication place name. Moreover, even if in copying the title-page from the previous edition had been an oversight such an improbable error, if it had occurred, would certainly have quickly necessitated a stop-press correction. Even if caught later it seems improbable that the publisher would have distributed the work as is. Moreover, it also seems improbable that this copy of the 1804 edition would have been subject to copyright restrictions. There is another important omission from the 1820 edition, that is, the editor, Israel ben Aryeh Leib’s apologia, at the end of the work.

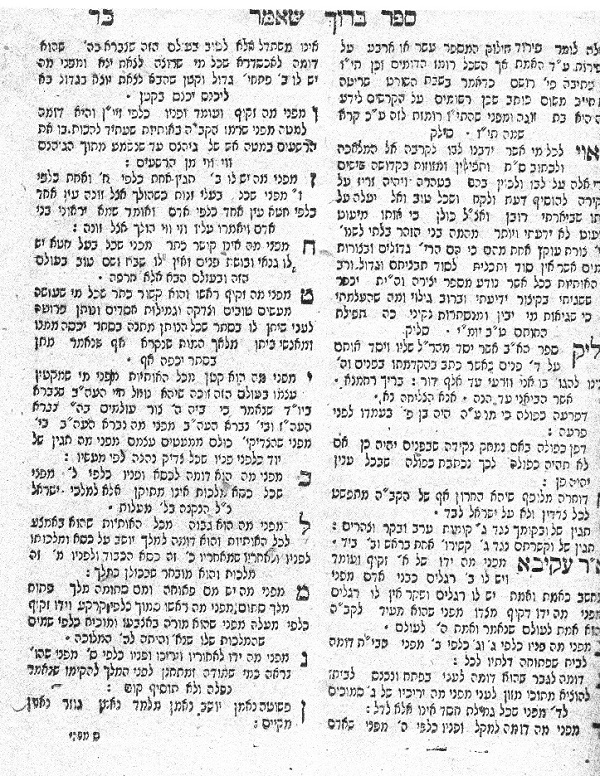

There are, however, in addition to those noted above, significant likenesses between the two works. First, excepting the front matter and apologia, the texts are set, line for line, in an identical manner. Moreover, the fonts appear to be alike. The reader should compare the two like pages below and drew his/her own conclusion. Perchance, the Minkowce printer acquired remaining copies of the 1804 edition, added the new front and back matter and reissued the work. Why did he do so?

1804, Baruch She’amar, Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

1820, Baruch She’amar , Courtesy of Virtual Judaica

Perhaps, and this is highly speculative, he felt that publishing this edition of Baruch She’amar as a pseudo-Shklov publication would give it greater marketability. If so, that should also have been true as well of other Minkowce publications. Or maybe he simply did not want to put his name on someone else’s work. Finally, we are left with the question as to why R. Judah Leib ben Zevi ha-Kohen’s approbation, which helps identify the place of publication, was printed with Baruch She’amar. Possibly including the approbation was important for the reasons that approbations were obtained, and it certainly would have been unconscionable, having gotten the Av Bet Din‘s approbation, to not print it.

We are left with a teku (an unresolved question).

[1] I would like to thank Eli Amsel of Virtual Judaica for bringing the 1820 edition of Baruch She-amar to my attention and Eli Genauer for reading the article and for his corrections.

[2] Hirsch Goldwurm, ed., The Rishonim (Brooklyn, 1982), p. 147.

[3] The Encyclopedia of Jewish life Before and During the Holocaust, editor in chief, Shmuel Spector; consulting editor, Geoffrey Wigoder; foreword by Elie Wiesel II (New York, 2001), III p. 1170; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Part I Indexes. Books and Authors, Bibles, Prayers and Talmud, Subjects and Printers, Chronology and Languages, Honorees and Institutes. Part II Places of print sorted by Hebrew names of places where printed including author, subject, place, and year printed, name of printer, number of pages and format, with annotations and bibliographical references II (Jerusalem, 193-95), pp. 689-95 [Hebrew].

[4] The Encyclopedia of Jewish II (New York, 2001.). p. 826). Vinograd II pp.457-458.

[5] Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim (Tel Aviv, 1951), bet 1431 [Hebrew]; idem. History of Hebrew Typography in Poland from its beginning in the year 1534 and its development to the present. . . . Second Edition, Enlarged, improved and revised from the sources (\(Tel Aviv, 1950), pp. 91,121, 123 [Hebrew]; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), pp. 457, 458, 692, 694 [Hebrew].

[6] Avraham Yaari, “Hebrew Printing in Minkovtsy,” Kiryat Sefer 19 (1942-43), pp. 274-75 [Hebrew]; idem. “Hebrew Printing in Shklov,” KS 22 (1945-46), pp. 141-42 [Hebrew].

23 thoughts on “An enigmatic Pseudo-Shklov edition of Barukh She’amar”

> However, to get the date 1820 the shin ש (300) in the verse has been replaced with a sameh ס (60) for the total of 580 = 1820.

Am I going crazy or does this math not work out? קסת is gematria 560, not 580.

The Yuds in Bnei Yehuda are enlarged. Two Yuds =20

Regarding the altered spelling in the chronogram, you wrote:

“However, to get the date 1820 the shin ש (300) in the verse has been replaced with a sameh ס (60) for the total of 580 = 1820.”

I think the substitution of the sameh is not just to arrive at the correct date. The publisher is making a witty play on words from “קשת”-(bow) to “קסת”-(quill). That is, “to teach the the children of Judah the art of being a scribe”-the topic of the book.

For a book on safrut (an exactiñg art) to have so many inaccuracies in coloform, printing location, who knows what else, I would have doubts about its contents.

And the article doesn’t mention Keset haSofer, the “Bible” of safrut published 15 years later

Thanks for sharing the infromative article. It is really valuable Information and helped me to get some nice ideas. Keep doing such great work.

I simply want to say I am all new to blogging and absolutely enjoyed you’re web site. Probably I’m planning to bookmark your blog post . You actually come with wonderful articles and reviews. Thanks for sharing your blog.

countries that do need lots of financial aids are those coming from Africa. i could only wish that their lives would become better**

It’s really a cool and useful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful article. Thanks for providing this info.

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Thank you so much, However I am going through difficulties with your RSS. I don’t know why I cannot join it. Is there anybody else having similar RSS problems? Anyone who knows the answer can you kindly respond? Thanks!!

After I initially left a comment I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Perhaps there is an easy method you are able to remove me from that service? Thanks.

This is the perfect blog for anyone who wants to understand this topic. You realize a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I really would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a fresh spin on a topic which has been written about for years. Great stuff, just excellent.

Do you believe past life experiences? Do you think past lives regression is real?

nice https://www.wooricasinokorea.com/margin 마진거래

좋아요 https://www.wooricasinokorea.com/theking 더킹카지노

I like it when folks come together and share thoughts. Great blog, continue the good work!

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful post. Many thanks for supplying this information.

It’s difficult to find experienced people for this topic, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

hello https://www.wooricasinokorea.com/casinosite 카지노사이트

win money and prizes

win money

Are you okay? I’m worried about you. Please be good to you.

where can you buy a newly printed baruch shaeamar sefer that is not an antique