Hebrew printing in Altdorf: A brief Christian-Hebraist Phenomenon

Hebrew printing in Altdorf: A brief Christian-Hebraist Phenomenon

By Marvin J. Heller[1]

Altdorf is remembered in Jewish history, when it is recalled at all, for the small number of Hebrew, Hebrew/Latin books printed there, beginning in the seventeenth century. Our Altdorf (old village), Altdorf bei Nürnberg, Bavaria, is one of several communities so named, others elsewhere in Germany, France, Switzerland, Poland, and even one Altdorf in the United States.[2] Again, our Altdorf, with the name to distinguish it from other Altdorfs, is Altdorf bei Nürnberg, that is, Altdorf near Nuremberg, a small Franconian town in south-eastern Germany, 25 km (15.53 miles) east of Nuremberg, in the district Nürnberger Land.

First mentioned in 1129, Altdorf was conquered by the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg in 1504. In 1578 an academy was founded in the city, becoming a university in 1622, one that lasted until 1809. Its most prominent student was the polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), a discoverer of differential and integral calculus. The university is important to us as it was a center of Christian-Hebraism. An instructor in Hebrew at the university was R. Issachar Behr ben Judah Moses Perlhefter, whom we shall meet, albeit briefly, below. Also active in Altdorf was the renowned Christian-Hebraist Johann Christoph Wagenseil, whom we shall also meet, but in much greater detail, further on in the article, as well as his predecessor at the University of Altdorf, Theodor (Theodricus) Hackspan.

Jewish settlement in Altdorf is not recorded, indeed Altdorf apparently had no Jewish community in the seventeenth century, which makes the publication of Hebrew books in Altdorf of unusual interest. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Christian-Hebraists, particularly in Protestant lands, studied and published Hebrew works for their own purposes, primarily philological and biblical titles, and translations of rabbinic works, often theological titles accompanied by glosses contesting the Jewish authors’ positions, all to better understand the sources of Christian theology and refute Jewish understanding of those works. Parenthetically, Christian-Hebraists often relied on both Jewish apostates and knowledgeable Jews for assistance with Hebrew, attempting to convert the latter to their beliefs.[3]

In Altdorf, in contrast, the Jewish related works are often polemics, including works that Jews might circulate in manuscript but were unable to print on their own behalf. The first Hebrew title printed in Altdorf was R. Yom Tov Lipmann Muelhausen’s Sefer Nizzahon (Liber Nizachon Rabbi Lipmanni . . .), published in 1644.[4] It was preceded and followed by Hebrew/Latin works, again, polemics, primarily comprised of the latter rather than the former, published in the seventeenth century, our subject period. Together with those bilingual titles and three works published in the 1760s, only sixteen works are recorded in a Hebrew bibliography for this period in Altdorf.[5]

A different enumeration of the titles printed in Altdorf, by the National Library of Israel, lists thirty-eight titles for Altdorf through 1765, again mainly Latin works with varying amounts of Hebrew, albeit dealing with Hebrew subjects, among them Kabbalah. However, for our period of interest, that is, the seventeenth century, ten titles only are recorded by the NLI. In addition, there are a number of works not in either enumeration, printed in Altdorf, that pertain to our subject, the works of Christian-Hebraists. Altdorf does not merit an entry in Ch. B. Friedberg’s multi-volume History of Hebrew Typography . . . and in terms of Hebrew printing it might be described as a cul-de-sac, its’ publications being of little import or lasting influence in the history of Hebrew typography. Nevertheless, its publications are of interest, being concerned with Jews, Judaism, and the study of Jewish texts by Christian-Hebraists.

This article, bibliographic in nature, is concerned with those seventeenth century titles published by Christian-Hebraists in Altdorf. In addition to the Hebrew titles a small number of the Christian-Hebraists’ Latin works will be noted as examples of their areas of interest and output, beginning with titles by Theodricus Hackspan. This will be followed in greater detail by a discussion of the first printed edition of the Sefer Nizzahon, translations of Mishnayot, and additional titles published by Wagenseil, among them Tela ignea Satanae, his most famous collection of polemic works.

I

Hackspan (1607-59), a noted Lutheran theologian and Orientalist, studied under renowned individuals in those fields, namely Daniel Schwenter (1585-1636) and Georg Calixtus (1586-1656). From 1636 Hackspan was at the University of Altdorf where he held the chair of Hebrew, was the first to publicly teach Oriental languages, and from 1654 was Professor of theology while retaining the chair of Oriental languages. It is said that “his close application to study and to the duties of his professorships so impaired his health that he died in the fifty-second year of his age. Hackspan is said to have been the best scholar of his day in Hebrew, Chaldee, Syriac, and Arabic.”[6] A prolific author, his works include titles printed as early as 1628 through 1633 in Jenae, and, from 1636, in Altdorf, with minimal Hebrew, beginning with Observationes Philologicae Ex Sacro Potissimum Penu Depromtae, with several coauthors. This was followed, in 1637, by a Hackspan title with somewhat more Hebrew De Necessitate Sacrae Philologiae in Theologia, this on comparative theology. Hackman also wrote works not related to Judaism, for example, Fides et leges Mohammaedis exhibitae ex Alkorani manuscripto duplici (1647) dealing with Islam, well beyond the scope of this article.

Assertio passionis Dominicae adversus Judaeos & Turcas. The first title in our series published in Altdorf by Theodricus Hackspan is his Assertio passionis Dominicae adversus Judaeos & Turcas (Assertive passion of the Lord against the Jews and the Turks), a small quarto (40: 24 pp.) Latin polemic with varying amounts of Hebrew, published in 1642.

Assertio passionis Dominicae adversus Judaeos & Turcas is primarily in Latin with very limited Hebrew and slightly more Arabic text. Several Hebrew sources are referenced. Among them “שלחן ערוך tractatu ארוך חיים Hilcot תשעה באב ושער תעניות.” There are only two full Hebrew passages, both set in rabbinic letters, as well as several brief lines in square letters. The passages, from Ta’anit 5b-6a and Yoma 39b respectively, with Latin translation and commentary, are:

He replied: Let me tell you a parable – To what may this be compared? To a man who was journeying in the desert; he was hungry, weary and thirsty and he lighted upon a tree the fruits of which were sweet, its shade pleasant, and a stream of water flowing beneath it; he ate of its fruits, drank of the water, and rested under its shade. When he was about to continue his journey, he said: Tree, O Tree, with what shall I bless thee? Shall I say to thee, ‘May thy fruits be sweet’? They are sweet already; that thy shade be pleasant? It is already pleasant; that a stream of water may flow beneath thee? Lo, a stream of water flows already beneath thee; therefore [I say], ‘May it be [God’s] will that all the shoots taken from thee be like unto thee’. So also with you. With what shall I bless you? With [the knowledge of the Torah?] You already possess [knowledge of the Torah]. With riches? You have riches already. With children? You have children already. Hence [I say], ‘May it be [God’s] will that your offspring be like unto you.’

Our Rabbis taught: During the last forty years before the destruction of the Temple the lot [For the Lord] did not come up in the right hand; nor did the crimson-coloured strap become white; nor did the westernmost light shine; and the doors of the Hekal would open by themselves.”[7]

Miscellaneorum Sacrorum libri duo. Another Hackspan title published in Altdorf, this in 1660, is Miscellaneorum Sacrorum libri duo: quibus accessit ejusdem Exercitatio de Cabbala Judaica, a translation of two miscellaneous sacred books (17 cm.: 5, 453, [33] pp.), printed by Georgii Hagen, typos & Sumptibus Universitatis Typographi together with Johannum Tauberum, Bibliopolam.

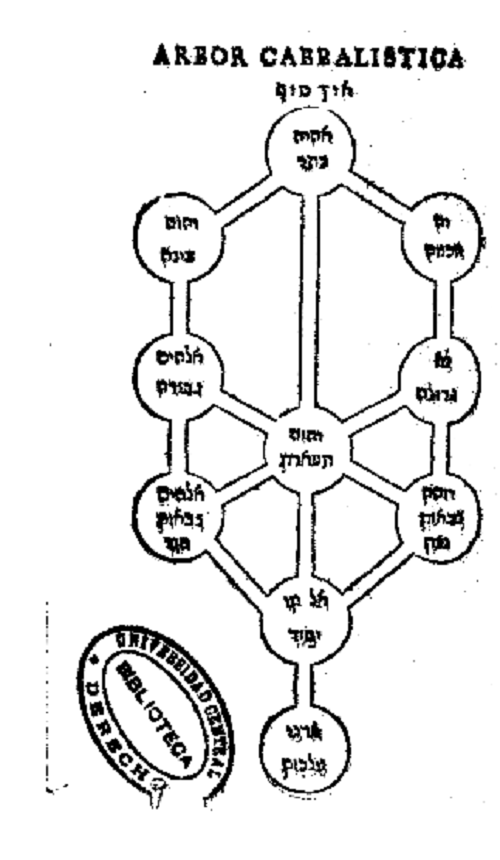

Miscellaneorum Sacrorum libri is a Latin introductory work comprised of introductions to Bible and Kabbalah, the latter section, from pp. 282-453, entitled “Cabbalae Judaicae brevis exposition.” Miscellaneorum Sacrorum libri duo was has two lead title-pages (above) and, in the Kabbalistic section, a diagram of the tree of life which enumerates and displays the sephirot (emanations).

Here too the text is primarily Latin with varying amounts, but generally brief Hebrew, including quotes from the Talmud and other varied Hebrew sources. For example (p. 417) “CXXXII. Nostra aetate quoque familia in scriptus eorum occurrunt (In our time in the writings of these men, too, was met by the family) Kimchi in Obadiam scripit” followed by seven lines of Hebrew beginning ארץ אדום אינה היום לבני אדום כי האומות נתבלבלו רובם הם בין אמונת בנוצרים . . . (Today the sons of Edom, because the nations were confused, are mostly Christians) . . . . Terra Idumea hodie non est filiorum Edom: nam populi confusi sunt (Edom today is the rule (that is the example) for the people were mixed up.

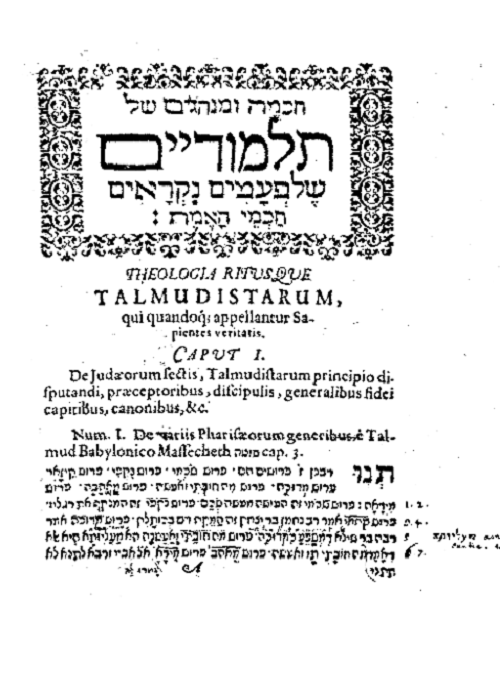

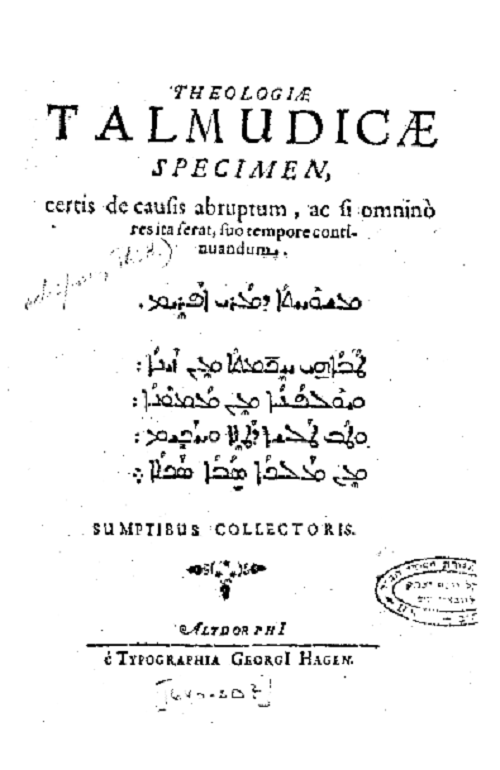

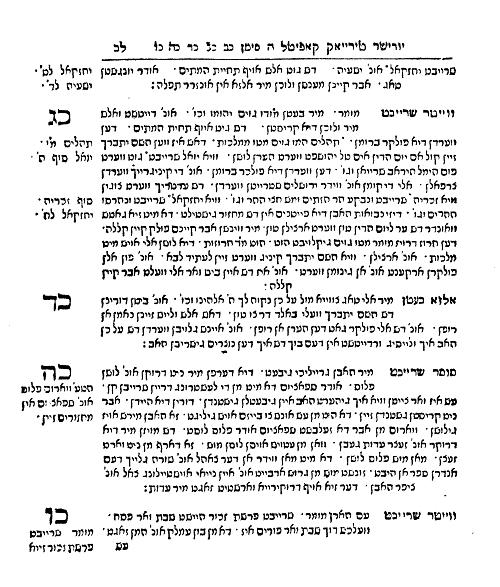

Theologiae talmudicae specimen. Yet another work by Theodricus Hackspan is Theologiae Talmudicae Specimen, certis de causis abruptum: ac si omninò res ita ferat, suo tempore continuandum. Theologiae Talmudicae Specimen (undated, 154 pp.), also printed by Georgii Hagen. The text of Theologiae Talmudicae Specimen is almost entirely in Hebrew, excepting Latin headers and marginal references. Despite the fact that Theologiae Talmudicae Specimen is almost entirely in Hebrew, in contrast to the other Hackspan titles noted here, it is set to read from left to right as if in Roman letters.

II

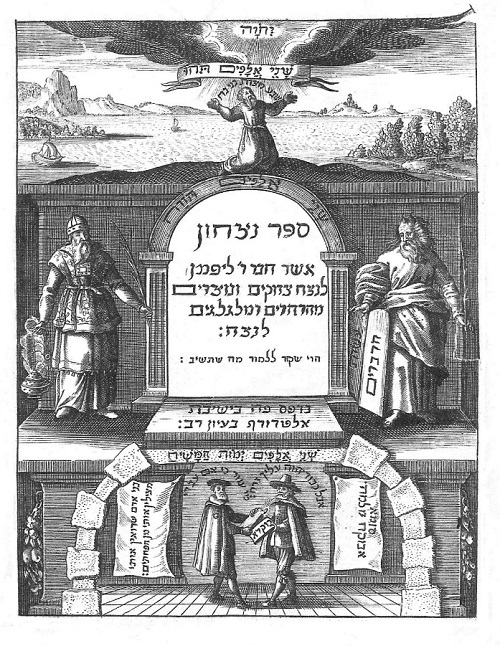

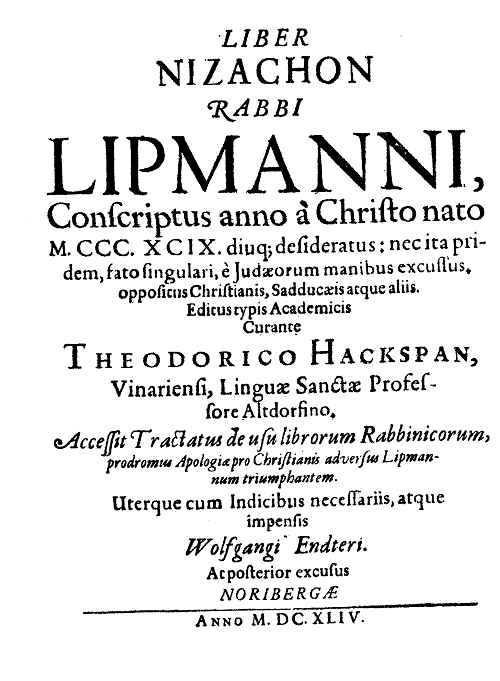

Sefer Nizzahon. The first Jewish title in our series published in Altdorf is R. Yom Tov Lipmann Muelhausen’s (d. 1459) Sefer Nizzahon (1644). This, the first printed edition of Nizzahon, was published in quarto format (40: [14], 512, 24 pp.), It is a polemic defense of Judaism and refutation of Christianity, here with a Latin translation by Theodore Hackspan, It was published so that Christians might be able to attempt to refute its arguments.

Muelhausen was one of the leading rabbinic figures of his time and a dayyan in Prague. His name, Muelhausen, likely derives from an earlier family residence in Muelhausen, Alsace. He studied under R. Meir ben Baruch ha-Levi (c. 1320-1390), Sar Shalom of Neustadt (14th cent.), and R. Samson ben Eleazar. In 1389, Muelhausen was one of a number of Jews incarcerated after an apostate named Peter accused them of defaming Christianity. In addition to his great rabbinic erudition, Muelhausen knew Latin and was familiar with Christian literature, making him a formidable polemicist. He was a prolific writer, his other works are on halakhah, philosophy, aggadah, piyyutim, and Kabbalah. In preparing Nizzahon Muelhausen utilized earlier Jewish polemical works, including an earlier thirteenth century Sefer Nizzahon Yashan (Nizzahon Vetus), with which this work is not to be confused. The effectiveness of Muelhausen’s Nizzahon may be gauged by the appearance of additional Latin editions and bitter attempts at refutations.

In a disputation in which Muelhausen represented the Jews he is reported to have been completely effective in his arguments, with the result that eighty Jews were martyred but Muelhausen miraculously survived.[8] Soon afterwards, in 1390, Muelhausen wrote Sefer Nizzahon for other Jews who had to respond to challenges from Christians. Nizzahon was copied but remained in manuscript until the publication of this edition, as the Church prohibited Jewish possession of a copy.

Christian scholars attempted to print Nizzahon for many years but were unable to obtain a manuscript. In 1644, Theodor Hackspan was successful in getting a copy. He had looked for a Nizzahon for a long time without success until he was informed that a rabbi in the neighboring small city of Schnattach had a copy but would not show it to anyone. Hackspan, together with some friends, paid an unwelcome visit to the rabbi, as if to engage him in a dispute. In the heat of the debate the rabbi took out his hidden manuscript of Nizzahon to look into it. Hackspan immediately seized the book from the rabbi’s hands, ran off with it to his carriage, and returned with it to Altdorf. Then, with a few of his students, they immediately copied the book and soon after printed the editio princeps of Sefer Nizzahon. Ora Limor and Israel Jacob Yuval Shoulson write that Hackspan printed Lippman’s text with care, not making any deliberate changes or alterations. Nevertheless, due to the poor knowledge of Hebrew of his “scribes . . . the book is full of mistakes, especially minor errors.” Meyer Waxman remarks that in his Latin introduction Hackman”attempts to refute Lippman in a dignified manner. Others, however, were not so generous.” [9]

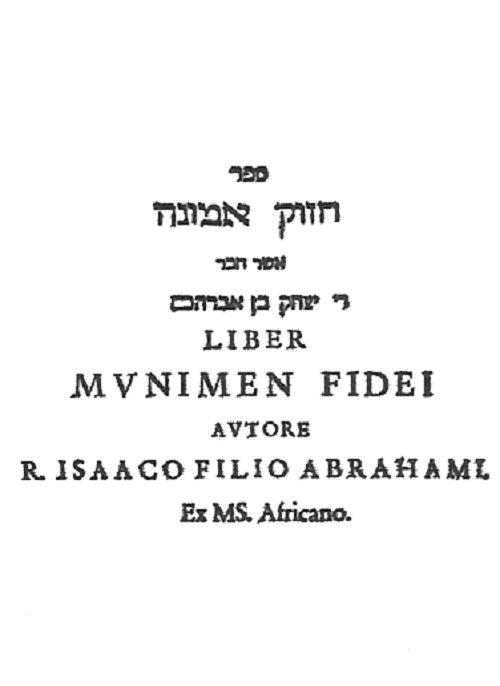

Nizzahon has an engraved Hebrew title page (above) followed by a Latin title page, which begins Liber Nizachon rabbi Lipmanni. . . .[10] Next is a dedication to Dn. Johan-Jodoco from Hackspan, introductions, a table of contents, and the Hebrew text set in a single column in rabbinic letters with marginal biblical references. Nizzahon is divided by the days of the week, further organized by books of the Bible, and subdivided into 354 sections, representative of the lunar year. These sections, not in order in the book, are refutations of Christian arguments (66 sections), explanations of dubious actions by the righteous in the Bible (39), explanations of difficult verses (41), reasons for precepts (34), refutations of the arguments of skeptics (55), against heretics and Karaites (47), and concluding with sixteen Jewish principles (48) to be read on Shabbat. Muelhausen refutes the Christian concepts of the Messiah, Immaculate Conception, and original sin. The Latin portion of the volume, printed in Nuremburg, begins on p. 211 and is paginated from right to left.[11]

Nizzahon was printed by Wolfgang Endter (1593 – 1659), a member of the well-known Nuremberg publishing family. The Hebrew title-pages states that it was printed in Altdorf, the Latin title-page gives Nuremberg at the place of publication. Nizzahon was reprinted in Altdorf in 1681 as part of Wagenseil’s Tela Ignea Satanae (below). The first Jewish edition of Nizzahon was published by Solomon Proops in Amsterdam (1709).

III

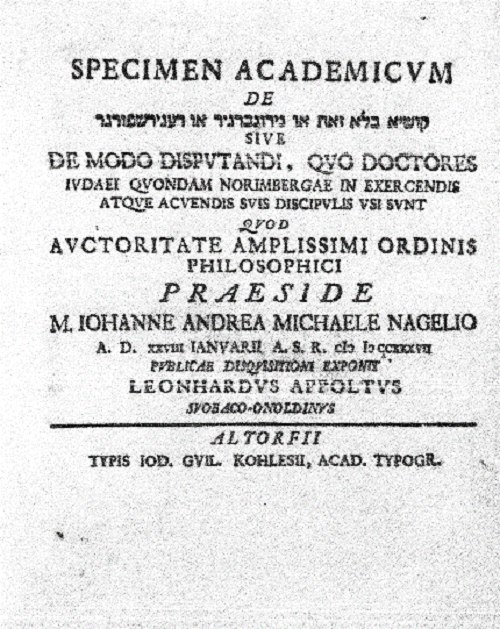

Kushya belo Zot o Niremberger o Regensburger.

Another work with Hebrew attributed to the Altdorf press was Kushya belo Zot o Nuremberger o Regensburger, a relatively small work (19 cm. 24 pp.), printed in 1670. This very rare work was described in an auction catalogue, the entry stating,

Kushya belo Zot o Niremberger o Regensburger

A composition regarding Talmudic disputation and the ‘chilukim’ method of the Ashkenazim by Leonard Appoltus, supervised by Prof. Johanne Andre Michael Nagelio.

Altorf, [c. 1670].

In Latin with segments in Hebrew.

24 p. 19 cm. Good condition. ‘Blo Zot’, Nirenburger’ and and ‘Regensburger’ are different types of questions that it was usual to ask in the ‘chuilukim’ method.

Very rare. Not in the Jerusalem National Library.

o.b $300 $400/700[12]

From the sale results sheet it appears that this item did not sell.

IV

In 1674 Christoph Wagenseil (1633-1705), professor of Oriental languages at the University of Altdorf from 1667, succeeded Hackspan, becoming the most prominent Christian-Hebraist in Altdorf. Wagenseil, learned his Hebrew from Enoch Levi, a Viennese Jew, and Jewish studies from R. Samuel Issachar Behr ben Judah Moses Eybeschuetz Perlhefter, (d. after 1701), a Prague scholar, kabbalist, and instructor in Hebrew in the University of Altdorf. Perlhefter was the author of Ohel Yissakhar, Ma’aseh Ḥoshen u-Ketoret, and Ba’er Heitev; served as rabbi in Mantua, leaving there over a dispute concerning the pseudo-Messiah Mordecai of Eisenstadt, a follower of Shabbetai Zevi, whom Issachar Behr had initially supported. He subsequently returned to Prague where he held the position of dayyan.

Perlhefter’s wife, Bella, taught Wagenseil’s daughter dancing and music.[13] Elisheva Carlebach elaborates, writing that Wagenseil, as did other Christian-Hebraists, often pressured the Jews who assisted them to convert. In this context, Wagenseil, unable to influence Perlhefter who was residing at the time in Altdorf, turned to Bella, then in Schnattach, inviting her to join his household for a family celebration. Bella responded, in literate Hebrew, that as she had a small child, whom she could not leave, “And if I carry him with me the cold is great, the snow is high, and a tiny child cannot tolerate the cold, for he or she has not been out of the house from the day of his or her birth and is not accustomed to the cold [Mrs. Perlhefter changed genders in mid sentence].” [14]

Wagenseil traveled widely as a youth, serving as a private tutor, and while in North Africa, Wagenseil acquired Hebrew manuscripts. Although “tarred” as an anti-Semite, together with other German Hebraists in the nineteenth century, Wagenseil was an accomplished Hebraist and, despite his opposition to Jewish beliefs, often defended Judaism against its more virulent enemies and their baseless charges. David Malkiel reports that Wagenseil had cordial relations with Jewish contemporaries.[15] Assessments of Wagenseil vary, from Heinrich Graetz, that “he was a good-hearted man, and kindly disposed towards the Jews,” to Frank E. Manuel, for whom he is one of three Christian-Hebraists, with Shickard and Eisenmenger, who “used their learning to cast a glaring light on those texts in the Talmud and later Jewish writings that were either blasphemous or full of hatred for Christians.” Wagenseil confuted Christian charges that the Talmud was blasphemous, senseless and jumbled, arguing that in it were matters of morality, wisdom, and medical advice; he also opposed blood libels. Furthermore, he maintained that Catholic censors had distorted the Talmudic text, particularly of Avodah Zarah.[16]

Wagenseil is credited with assembling the first comprehensive study of Jewish observances and ceremonies by a Christian. Jonathan I. Israel notes that Wagenseil considered much of what he found superstitious and absurd, and that his motivation was to bring Jews to Christianity. Nevertheless, “for all that an unmistakable admiration for Jewish life and Jewish life-style insistently creeps through.” He quotes Wagenseil, who wrote in the forward to the apostate Friedrich Albrecht Christiani’s Der Jüden Glaube und Aberglaube (Leipzig, 1705),

that they show far more care, zeal, and constancy in all this (their religious duties) than Christians do in practicing their true faith, and that, furthermore, they are far less given to vice; rather they possess many beautiful virtues, especially compassion, charity, moderation, chastity, and so forth . . .[17]

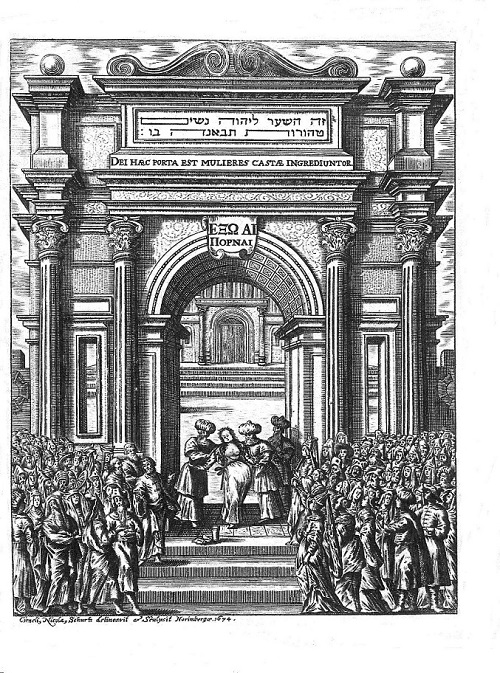

Sotah (the suspected adulterous woman) has numerous illustrations, several being full page, and a detailed attractive copper-plate title page of the Sotah (the wife accused of adultery) being taken by the priests to be tested. The volume opens with a full page depiction of the Sotah being taken to be tested by the priests.

The verso has verses in Latin from Psalms and the Christian Bible. The title page in red and black, begins, Hoc est: liber mischnicus de uxore adulterii suspecta (this book is a work concerning a woman suspected of adulterous behavior). Reading from left to right, the volume begins with considerable prefatory material, including several indices, one in Hebrew, correctiones Lipmannianae (10-81), corrections to Hackman’s edition of the Sefer ha-Nizzahon based on two other manuscripts he was able to obtain, and the text, which has separate pagination.

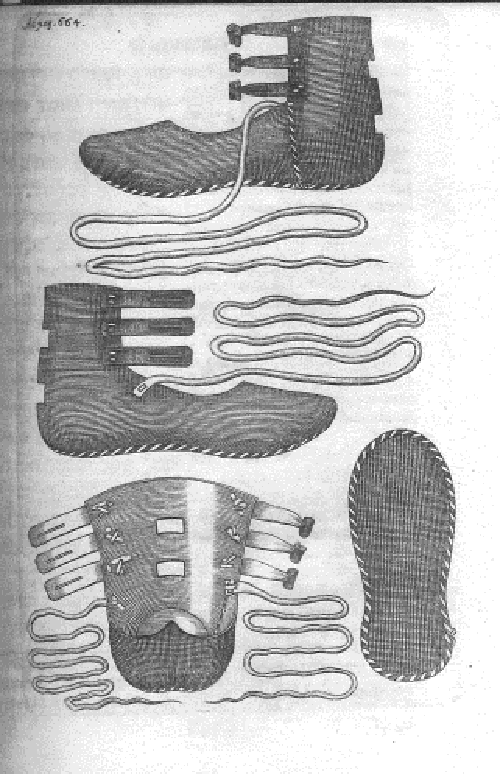

Within the text the Mishnah is always in the left margin in square unvocalized Hebrew, the translation in the right column, accompanied by an extensive Latin commentary with occasional Hebrew, with excerpts from the gemara, including most of the aggadah in the Ein Ya’akov, on this tractate. The volume has numerous illustrations, several being full page. Among them are depictions of the priest wearing talit and tefillin with their straps for the head and arm, magen davids, halizah shoes, coins, and an undressed woman with skull and cross. Negaim was the next tractate translated by Wagenseil, to prove that the Talmud contained valuable and interesting material on medicine.[18]

Tractates Avodah Zarah and Tamid. Another translation of Mishnayot tractates, this of Avodah Zarah and Tamid, prepared by the Christian-Hebraist Gustavo Peringero (Gustav von Lilienbad Peringer, 1651-1705), a student of Johann Christoph Wagenseil. Peringero, (1633–1705), was professor of Oriental languages at Upsala (1681- 1695) and afterwards librarian at Stockholm. Charles XI, king of Sweden, who reputedly had an extraordinary interest in Jews and even more so in Karaites, sent Peringero to Poland to learn about the latter and perhaps to attempt to convert the Karaites to Christianity, for, as Graetz notes, they did not have “the accretion of traditions, and were said to bear great resemblance to the Protestants,” nor were they “entangled in the web of the Talmud.” [19]

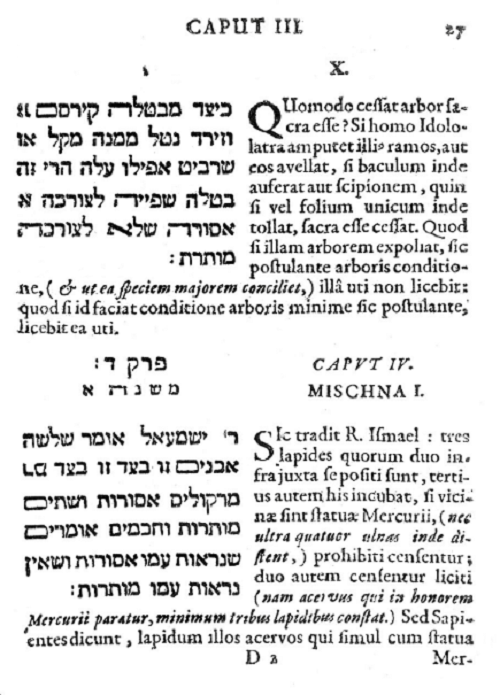

This edition of Mishnayot of tractates Avodah Zarah and Tamid in Hebrew with accompanying Latin translation and annotations by Peringero was published in 1680 by Johannes Henricus Schönnerstadt in a small octavo format (80: [7], 78 pp.).The title page of this volume is, excepting a Hebrew header, entirely in Latin. It states that it is comprised of two codices, primarily about idolatry, and secondly about sacrifices in the time of the Temple. The title page is followed by a dedication to Dominae (Mistress) Ulricae Eleonorae, wife of Charles XI, a preface in Latin with occasional Hebrew, and then the text.

Reading from left to right, the Mishnayot are in the left column, the integrated translation and glosses in the right column. Avodah Zarah concludes on p. 43 and Tamid begins immediately after on the following page. Peringero’s translation of Avodah Zarah was inserted by Wilhem Surenhusius (1666-1729) in his Versio Latina Mischnae (1698-1703). In addition to these tractates, Peringero also translated Abraham Zacuto’s Sefer Yuhasin, portions of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (Upsala, 1692), and several other works into Latin. He was also the author of Dissertatio de Tephillin sive Phylacteriis (Upsala, 1690). [20]

In addition to tractates Avodah Zarah and Tamid the printer, Johannes Henricus Schönnerstadt, also published separate editions of Shekalim and Sukkah at this time, also with Latin, but not translated by Peringo.

IV

Returning to Wagenseil, we come to two very different works. The first, although chronologically the later of the two, and not an Altdorf publication, is Belehrung der Judisch-Teutschen Red-und Schreibart (An Instruction Book in the Method of Speaking and Writing Judeo-German, Koenigsberg, 1699). This is, as the title suggests, a Yiddish grammar with a “loose Yiddish version (with German translation) of Hilkhot Derekh Eretz,” a rabbinic work on ethical behavior. Also included is a Yiddish account (with German translation) of the Fettmilch uprising in 1614 in Frankfurt on the Main, as well as selections from tractate Yevamot on levirate marriage as well as the entire tractate Neg’aim on leprosy with notes, this in order to aid in teaching Hebrew.[21]

The second and Wagenseil’s most famous collection of Jewish polemical literature, Tela ignea Satanae, in which Wagenseil, among other subjects, includes his responses to Sefer Ha-Nizzahon. Wagensiel travelled widely, through Spain and into Afric Belehrung e a, to collect these manuscripts.[22]

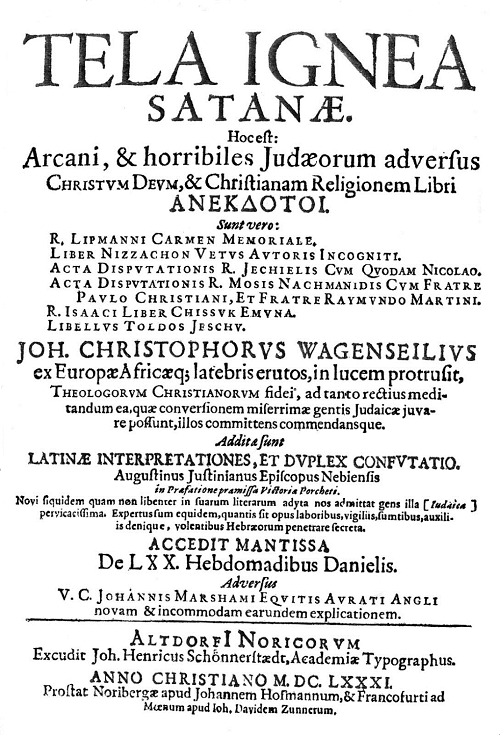

Tela ignea Satanae. Published in 1681 by Wagenseil in quarto format (40: [2], 635, [12]; 60; 260; [2], 100; 45; 480, [1] pp.) Tela ignea Satanae, perhaps Wagenseil’s best known work, is comprised of six polemical anti-Christian works, almost all not previously printed.

The first title page, printed in red and black, has the full title of Tela ignea Satanae. Hoc est: Arcani, et horribles Judaeorum adversus Christum Deum, et Christianam Religionem Libri (Flaming Arrows of Satan; that is, the secret and horrible books of the Jews against God and the Christian religion). After the verse the title-page states,

John Christopher Wagenseil thrusts these forward into the light, bringing them together and entrusting them, dug out from the hiding places of Europe and Africa, to the faith of Christian Theologians, that they may more rightly consider those things, which are able to aid the conversion of that wretched Jewish race. Added are: Latin Interpretations, and Two Confutations. Augustine Justianus Bishop at Nebiensis in the Forward Preface of Victoria Porchetus. I know how unwillingly that most stubborn (Jewish) race admits us into the most secret parts of their literature. I have tried by all means, however great the task, with toil, sleeplessness, expense, with willing helpers finally, to penetrate the secrets of the Hebrews.[23]

The facing page has a full front-piece portrait of Wagenseil. In two volumes, the work begins with a Latin introduction, followed by the six books, each with its own title page with Hebrew headers and Latin text, a Latin introduction (refutation), and then the text in two columns comprised of facing Hebrew and Latin.

That these books were not previously printed but rather circulated among Jews in manuscript only, or where printed were done so by Christian Hebraists with Latin translation and refutation, is due to their polemic and inflammatory content. As a result, these books today exist with variant texts. Tela ignea Satanae, as noted above, is comprised of six independent books, listed below, several described afterwards in somewhat greater detail:

Nizzahon, Polemic in defense of Judaism by R. Yom Tov Lipmann Muelhausen. Printed previously in Altdorf/Nurenburg, 1644 (see above).

Nizzahon, anonymous polemic in defense of Judaism.

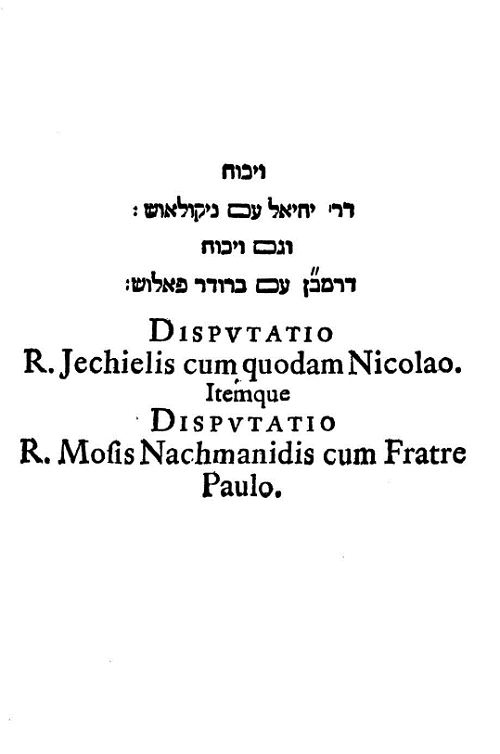

Vikku’ah Rabbenu Yehiel mi-Paris, record of the disputation between R. Jehiel of Paris and Nicholas (dispute over the Talmud in Paris in 1240, below, 1681).

Vikku’ah ha-Ramban im broder Paulus, record of the disputation between the Ramban (Moses ben Nahman, Nahmanides) and the apostate Pablo Christiani in 1263 before King James of Aragon.

Hizzuk Emunah, anti-Christian polemic by the Karaite scholar, Isaac ben Abraham Troki.

Jeshu, negative and, from a Christian perspective, highly blasphemous account of the life of Jesus.[24] [25]

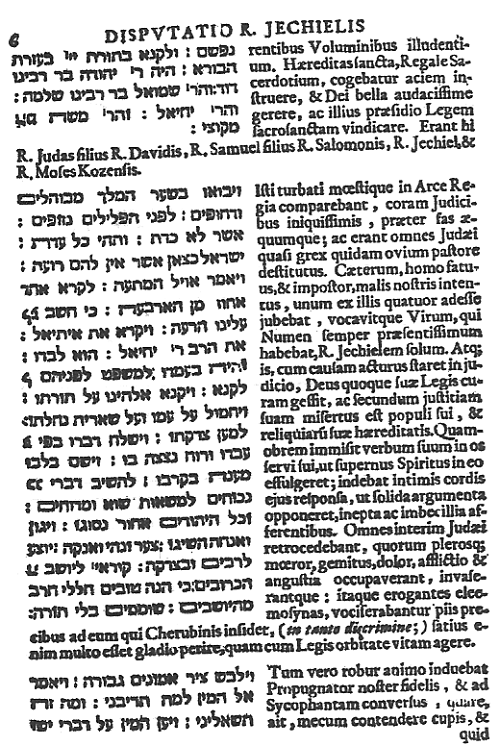

Vikku’ah Rabbenu Yehiel im Nicholas Jehiel ben Joseph of Paris. This is a record of the disputation held in Paris on Monday, June 25, 1240, attributed to R. Jehiel ben Joseph of Paris. Jehiel, one of the leading Ba’alei Tosafot, was a student of R. Judah ben Isaac (Sir Leon), whom he succeeded as rosh yeshivah in Paris. Among Jehiel’s students was his son-in-law, R. Isaac of Corbeil (Sefer Mitzvot Katan, Semak). Jehiel was the author of tosafot quoted by many rabbis and included in those tosafot known as our tosafot. He is also frequently referenced in the Torah commentary Da’at Zekenim. Because of his prominence Jehiel was selected as a primary representative of the Jewish community in the disputation over the Talmud resulting from the charges leveled against it by the apostate Nicholas Donin. The record of that disputation, generally known as Vikku’ah Rabbenu Yeh iel mi-Paris, is the third work in Wagenseil’s Tela ignea Satanae (above, 1681).

The Vikku’ah follows the same pattern as the other works in Tela ignea Satanae, that is, it has a bilingual Hebrew-Latin title page, followed by a Latin preface, and the text in two columns in facing Hebrew and Latin. Donin’s denunciation of the Talmud included thirty‑five charges which primarily stated that Jewish emphasis on the Oral Law was in itself a blasphemy against the holiness of Scriptures recognized by Jew and Christian alike; the Talmud overtly fostered anti‑Christian attitudes and contained blasphemous statements offensive to Christianity; and that it was irrational, and morally and intellectually offensive.

The trial was presided over by the Queen Mother Blanche, who was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. The judges were high Church dignitaries, such as the Archbishop of Sens, the Bishop of Paris, and the Chaplain to King Louis IX, none of whom knew Hebrew. Jehiel, although the primary Jewish spokesman, was assisted by R. Moses ben Jacob of Coucy (Semag), R. Judah ben David of Melun, and R. Samuel ben Solomon of Chateau‑Thierry (all 13th century). Although Jehiel defended the Talmud, noting inter alia, that Donin was the real heretic, justifiably excommunicated by the Jewish community fifteen years before the debate. His arguments were to no avail, for the matter had been predetermined from the outset. Even before the court’s formal decision was rendered, it had been decided to burn the condemned books. In June, 1242, twenty‑four wagon loads of Hebrew books, containing thousands of volumes, were seized and burned in Paris. Jehiel remained for some time in Paris, teaching students from memory. In 1260, Jehiel went up to Eretz Israel, effectively ending the period of the Ba’alei Tosafot.[26]

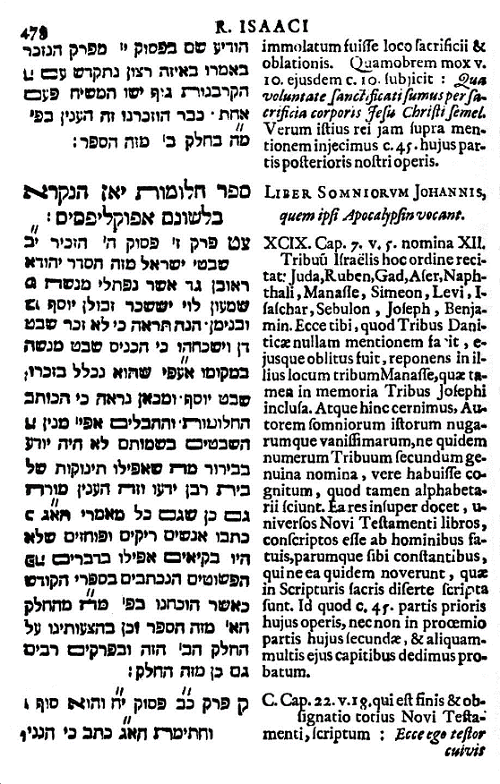

Hizzuk Emunah. Anti-Christian polemic by the Karaite scholar, Isaac ben Abraham Troki (c. 1533-c. 1594). Hizzuk Emunah is the fifth work in Wagenseil’s Tela ignea Satanae below, 1681). Troki is known by his birthplace, Troki (Trakai), capital of Lithuania until 1323 and home to the most important Karaite community in Lithuania. He was, from the age of twenty, the secretary-recorder of the Karaite General Assembly which met there in 1553. Author of a work on shehitah and religious poetry, Troki became the foremost Karaite scholar in Eastern Europe, serving as dayyan to both Karaite and rabbinic Jews. He studied Bible and Hebrew studies under the Karaite scholar Zephaniah ben Mordecai, and had Christian teachers for Latin and Polish literature. Engaging in dialogues with Christian clergyman of different persuasions, Troki became fluent in Polish and Latin and familiar with their theology and arguments against Judaism. It was those conversations that prompted Troki to write Hizzuk Emunah. Written in the last year of his life, Hizzuk Emunah was completed by Troki’s student, Joseph ben Mordecai Malinovski.

Wagenseil obtained a copy of the manuscript in 1665 on a trip to Ceuta, North Africa. He translated Hizzuk Emunah into Latin, in which form it was widely used not only by Christian missionaries but also by opponents of Christianity, such as atheists, French philosophes, among them Voltaire. Hizzuk Emunah follows the same format as the other polemic works in Tela ignea Satanae, that is, it has its own Hebrew-Latin title page, a Latin introduction, and then the text, in two facing Hebrew and Latin columns. The book, in quarto format, is in two parts comprised of ninety-nine chapters. In the first chapter, Troki begins by questioning the authenticity of the Christian messiah, arguing against his pedigree, acts, the time in which he lived, and the fact that he did not fulfill the promises expected of the Messiah.

As an example of the first argument, Troki writes that he cannot be of Davidic descent due to the concept of virgin birth and that even apart from that, the relationship of Joseph to David is wanting in proof. He also notes contradictions in the Christian Bible on that and other subjects, and compares the Hebrew Bible and Gospels. Most of Troki’s arguments are based on biblical texts, accounting for its effectiveness against Christian arguments. Nevertheless, he also utilizes rabbinic sources, so that Hizzuk Emunah has been accepted by rabbinic authorities, perhaps unique for a Karaite work.[27]

Hizzuk Emunah is considered one of the most effective polemic works. Although circulated widely in manuscript, Hizzuk Emunah was not printed by and for Jews until the Amsterdam edition of 1705. It has been frequently reprinted, translated into Yiddish (Amsterdam, 1717), English by Moses Mocatta (London, 1851), German (Sohran, 1865), and Spanish as Fortificación de la Fe (1621), extant in manuscript.

Wagenseil would publish several additional Hebrew/Latin collections and works, among them Exercitationes sex varii argumenti (1697); Denunciatio Christiana de Blasphemiis Judæorum in Jesum Christum (1703); and Disputatio Circularis de Judæis (1705) as well as several titles published elsewhere. As might be expected, Wagenseil’s influence in this field was considerable, his students also becoming Christian-Hebraists, for example, Peringer above, and our final Altdorf imprints, the first by a student of Wagenseil.

Jesus in Talmude. Our final works are Jesus in Talmude and Der Jüdische Theriak. The former is dissertation submitted at the University of Altdorf by Rudolf Martin Meelführer (Rudolfo Martino Meelführero, 1670–1729) in 1699, and described by Peter Schäfer as “the first book solely devoted to Jesus in the Talmudic literature;” the latter a refutation by R. Solomon Ẓevi Hirsch Aufhausen (Openhausen, Ufenhausen, of Aufhausen) in Yiddish of an anti-Jewish work. Meelführer was also a Christian-Hebraist, teaching in Altdorf and afterwards as adjunct in philosophy at Wittenberg. The dissertation is important as it was the first study fully devoted to the subject. Meelführer, in contrast to Wagenseil, was almost immediately forgotten.[28] Here too the work is primarily in Latin, but includes examples of the Talmudic text in Hebrew, from early editions of the Talmud, as the later editions available to Meelführer were censored and omitted many of the passages he refers to. Meelführer appears to primarily rely on secondary sources for Talmudic entries, notably R. Gedaliah ben Joseph ibn Yahya’s (1515-1587), Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (Venice, 1586).[29] An example of the text brought by Meelführer is Sanhedrin 42a (below), censored from most editions of the Talmud,

On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, ‘He is going forth to be stoned because he has practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy. Anyone who can say anything in his favor, let him come forward and plead on his behalf.’ But since nothing was brought forward in his favor he was hanged on the eve of the Passover! – “Ulla retorted: Do you suppose that he was one for whom a defence could be made? Was he not a Mesith [enticer], concerning whom Scripture says, Neither shalt thou spare, neither shalt thou conceal him? With Yeshu however it was different, for he was connected with the government [or royalty, i.e., influential].

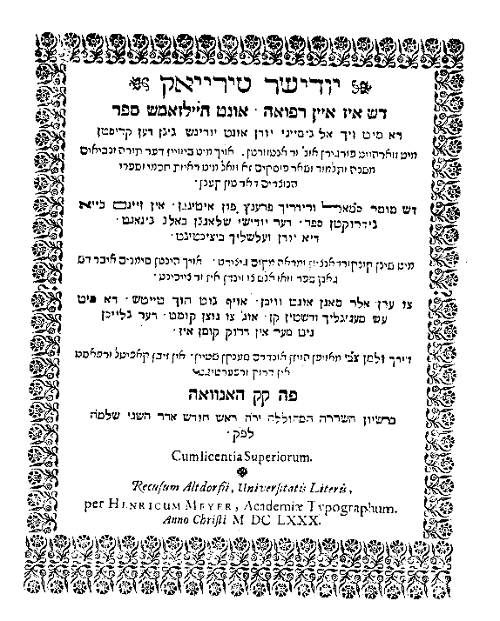

Der Jüdische Theriak (the Jewish Medicine) by Zalman Ẓevi Hirsch Aufhausen is a point by point refutation of Jüdischer Abgestreifter Schlangenbalg (The Jewish Serpent’s Skin Stripped) by the apostate Samuel Friedrich Brenz of Ettingen. Converted to Christianity in 1610, Brenz wrote Jüdischer Abgestreifter Schlangenbalg (Hanau, 1614) in “the thirteenth year after my rebirth.”[30] Der Jüdische Theriak, first printed in Hanau in 1615, was reprinted in in Altdorf in 1680 by Henricum Meyer, Academiae Typographu, as a small quarto (40: 36, [1] ff.), the text in old Yiddish set in Vaybertaytsh, a type generally but not exclusively reserved for Yiddish books, so named because these works were most often read by the less educated and women.[31] Given that it is a Jewish refutation of Christian ant-Jewish polemics its publication in Altdorf was likely done for the same purpose as Nizzahon, so that Christians might be able to attempt to refute its arguments.[32] In Jüdischer Abgestreifter Schlangenbalg Brenz collected all of the accusations made against Jews, accusing them of making derogatory and blasphemous remarks against the founders of Christianity and the Church, fostering animosity, and stating that the Talmud permits Jews to cheat Christians.

Zinberg notes that there is scant information about Aufhausen and what is known is surmised from remarks in Der Jüdische Theriak. Zinberg conjectures that Aufhausen (b. c. 1565-60) was an itinerant who, driven from his home by “evil Jews” travelled widely, broadening his world-view and culture, knowledgeable with German, knew Luther’s translation of the Bible, and was familiar with Flavious Joseph, Buxtorf the Elder, Pica della Mirandola, and Johannes von Reuchlin on the Kabbalah among others. Furthermore, Aufhausen “displays great knowledge of Talmudic literature, and that he wrote elegant Hebrew is attested to by the poem written in the well known azharot-meter on the front page of the Teryak.” Zinberg infers from Aufhausen’s remarks that he was a shohet and mohel (ritual slaughterer and circumciser) but these professions did not provide well for Aufhausen, his wife, and six children “who were not always well fed.”[33]

Morris M. Faierstein writes that Der Jüdische Theriak is unique, it is the only Jewish response in Yiddish to anti-Jewish polemics by Christians and Jewish apostates in early modern Germany and the only such work printed in Germany.[34] Zinberg quotes Aufhausen that Der Jüdische Theriak is an antidote to the venomous bite of the anti-Jewish snake, that is, Brenz’s work. Aufhausen describes Brenz as “a terrible usurer,” and if one added together all the horses on which he loaned money one could put in the filed a regiment of riders, which is what brought him to baptism, noting that the Jews hated him for his ugly deeds pushing him way with both hands.” Brenz is a “frightful ignoramus and a petty, good for nothing creature, his diatribe lacks any system or order.[35] In his introduction, Aufhausen informs how he came to write Der Jüdische Theriak. Benz’s book was

placed before me, and worthy people waved it under my nose. As a result I called the aforementioned apostate a liar, as I continue to do the present. On Monday, the seventh of Ab, he [Benz] he rode up to my door in a violent manner and threatened me and wanted to kill me. He publicly confirmed the wickedness of his book in front of Jews and Christians, said that it was all true and just and wanted to continue persecuting Jews. However, I sanctified the name of God in response to his desecration of God’s name and called him a liar to his face and swore to write a book against his lies . . .[36]

Der Jüdische Theriak is comprised of seven chapters, each addressing a specific group of accusations. Aufhausen cites numerous examples from the Talmud to show that Jews are commanded to show mercy and friendliness to non-Jews, and those few laws that are not friendly are directed against pagans, not Christians.[37] Der Jüdische Theriak is also directed towards women, for, as Carlebach notes, Christian missionaries had introduced Yiddish into their conversion material to make them accessible to women. Aufhausen refutes their claims writing for “common Jews and Jewesses.”[38] In the final chapters of Der Jüdische Theriak Aufhausen includes an appeal for tolerance advocating equal treatment for all, both Jews and Christians,

I have shown above that [tractate] Baba Kamma and [tractate] Avodah Zarah write: “A heathen who studies Torah and studies the law of Moses is as good as the high priest.” Thus anyone who studies the Law and does not ridicule it, he is an honest person and is highly honored. It is the same whether Christian or Jew. . . .

I had this book printed in Yiddish in the Hebrew alphabet so that someone will know how to respond to Christians in conducive circumstances, and also to understand from this and keep in mind what a great sin it is to deceive Christians, with words or deeds.[39]

The study of Jewish texts by Christian-Hebraists proved to be a passing phenomenon. By mid-eighteenth century the interest of Christian-Hebraists in rabbinic literature and studies had diminished.[40] In Altdorf, in contrast to other locations where, as noted above, Hebrew works, primarily philological and biblical titles and translations of rabbinic works, often theological titles accompanied by glosses contesting the Jewish authors’ positions, were studied by Christian-Hebraists for their own purposes to better understand the sources of Christian theology and to refute Jewish understanding of those works, the emphasis of those studies here was primarily for polemic purposes. Wagenseil, although his object was not always antithetical to Jewish texts, is remembered today as being among the leading exponents of the Christian-Hebraist movement. His works, several described here, as well as those of his contemporaries in Altdorf, represent an attempt by Christian-Hebraist scholars to understand and refute Jewish beliefs. Despite being, from several perspectives, among those of history, a failed and futile effort, it represents an interesting intellectual endeavor.

[1] I am indebted to Eli Genauer for reading the text and his comments, several noted below and to R. Jerry Schwarzbard, the Henry R. and Miriam Ripps Schnitzer Librarian for Special Collections for his assistance. Images are courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef; Yitzhak;Bayerische StaatsBibliothek; the Library of Congress; Hathi Trust; Hebrewbooks.org; and R. Eli Amsel, Virtual Judaica.

[2] The other Altdorf’s are, in Germany, Altdorf, Lower Bavaria, Landshut, Bavaria; Altdorf, Böblingen; Altdorf, Esslingen; Altdorf, Rhineland-Palatinate, Südliche Weinstraße; and Weingarten (Württemberg) or Altdorf: in Swiitzerland, Altdorf, Jura or Bassecourt; Altdorf, Schaffhausen; and Altdorf, Uri: in France, Altdorf, Bas-Rhin” in Poland, Stara Wieś, PszczynaStara Wieś; and Silesian Voivodeship; and in the United States, Altdorf, Wisconsin.

[3] An unanticipated result of the Christian-Hebraists’ efforts, suggested by Eli Genauer in a private correspondence, is that readers of the Christian-Hebraists works might possibly have been influenced in another direction, suggesting that “even though the Christian scholars published these books to show the errors of Judaism, there might have been some people who say “‘hey, the Jews have some pretty good points.’”

[4] Aron Freimann, “A Gazetteer of Hebrew Printing” (1946; reprint in Hebrew Printing and Bibliography, New York, 1976), p. 268; Moshe Rosenfeld, Hebrew Printing from its Beginning until 1948. A Gazetteer of Printing, the First Books and Their Dates with Photographed Title-Pages and Bibliographical Notes (Jerusalem, 1992), p. 64 no. 618 [Hebrew].

[5] Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 23 [Hebrew]. Vinograd notes three additional works, a Mishnayot, printed in 1860, Toldot Jeshu, in a collection of Wagenseil’s works (below), and an undated edition of Hochmah u-Minhag shel Talmidim.ge

[6] John McClintock, James Strong “Hackspan, Theodor” Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, ttps://www.studylight.org/encyclopedias/tce/h/hackspan-theodor.html. (New York, 1870).

[7] Translations are from The Soncino Talmud, Judaica Press, Inc. (Brooklyn, NY, 1990).

[8] Israel Moses Ta-Shma, “Muelhausen, Yom Tov Lipmann,:EJ 14, pp. 595-59.

[9] Ora Limor and Israel Jacob Yuval “Skepticism and Conversion: Jews, Christians, and Doubters in Sefer Nizzahon,” in Hebraica Veritas?: Christian Hebraists and the Study of Judaism in Early Modern Europe, Allison P. Coudert and Jeffrey S. Shoulson, editors (Philadelphia, 2004), p. 166; Meyer Waxman, A History of Jewish Literature (1933, reprint Cranbury, 1960), II p. 51.

[10] Eli Genauer, in a separate correspondence, brought the following to my attention concerning the text at the bottom of the title-page of Sefer Nizachon. “I was curious about the script written at the bottom starting with ‘Suma Avuka Zu Lamah’ . . . continuing on to the other side start from top line 7th word…B’Sefer HaNitzachon…I think the author is using this as an example of Jewish title pages and didn’t realize it was printed by a Christian. It is actually a Gemara in Megillah 24b which goes like this

אמר ר’ יוסי: כל ימי הייתי מצטער על מקרא זה (דברים כח, כט) “וְהָיִיתָ מְמַשֵּׁשׁ בַּצָּהֳרַיִם כַּאֲשֶׁר יְמַשֵּׁשׁ הָעִוֵּר בָּאֲפֵלָה”. וכי מה אכפת לֵיה [=לו] לעיוור בין אפלה לאורה? עד שבא מעשה לידי. פעם אחת הייתי מהלך באישון לילה ואפלה וראיתי סומא שהיה מהלך בדרך ואבוקה בידו. אמרתי לו, בני, אבוקה זו למה לך? אמר לי, כל זמן שאבוקה בידִי, בני אדם רואין אותי ומצילין אותי מן הפחתין ומן הקוצין ומן הברקנין.

Fascinating. I’m not sure what they were trying to point out but I wouldn’t be surprised if it had Christian implications.”

The above text (Megillah 24b) states “R. Jose said: I was long perplexed by this verse, And thou shalt grope at noonday as the blind gropeth in darkness.5 Now what difference [I asked] does it make to a blind man whether it is dark or light? [Nor did I find the answer] until the following incident occurred. I was once walking on a pitch black night when I saw a blind man walking in the road with a torch in his hand. I said to him, My son, why do you carry this torch? He replied: As long as I have this torch in my hand, people see me and save me from the holes and the thorns and briars.”

[11] J. Rosenthal, “Anti-Christian Polemics from its Beginnings to the End of the 18th Century,” Areshet II (Jerusalem, 1960), p. 148 no. 70 [Hebrew]; Waxman, pp. 545-51.

[12] Judaica Jerusalem, “Rare Books, Manuscripts, Documents, and Jewish Arts” (Jerusalem, October 14, 1993), no. 4.

[13] Louis Isaac Rabinowitz, “Perlhefter, Issachar Behr ben Judah Moses” Encyclopedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, vol. 20. (2007), vol. 15, p. 777. Concerning the personal life of Bella Perlhefter and letters to Wagenseil see Elisheva Carlebach “Introduction to The Letters of Bella Perlhefter,” Early Modern Jewries, I (2004, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT), pp. 149-57: https://fordham.bepress.com/emw/emw2004/.

[14] Elisheva Carlebach, Divided Souls: Converts from Judaism in Germany, 1500-1750 (New (Haven & London, 2001), pp. 204-05). Carlebach continues that Wagenseil subsequently invited her again, this time writing to Samuel Issachar Behr, to which she responded that “‘you have further written to me about coming to your place, to teach dance to the only, wonderful daughter of your master the great scholar, whose name escapes me, May God watch over her, it is puzzling to me that you add, ‘and to teach her to play the zither,’ for you know that from the day of my mother’s death, I took an oath not to play any musical instrument, and now how can I violate my oath? But it is possible that sometime I will come to teach her to dance.”

[15] David Malkiel, “Christian Hebraism in a Contemporary Key: The Search for Hebrew Epitaph Poetry in Seventeenth-Century Italy,” Jewish Quarterly Review 96:1 (Philadelphia, 2006), pp. 126, 136.

[16] Frank E. Manuel, The Broken Staff: Judaism Through Christian Eyes (Cambridge, Mass., 1992), var. cit.

[17] Jonathan I. Israel, European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism 1550-1750 (Portland, 1998) pp. 189-90.

[18] Elisheva Carlebach, “The Status of the Talmud in Early Modern Europe,” in Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein, eds. Sharon Liberman Mintz and Gabriel M. Goldstein (New York, 2005), pp. 87-89; Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews (Philadelphia, 1956), History of the Jews V, pp. 185-87.

[19] Graetz, History of the Jews V, pp. 182-83. Concerning Peringer’s mission, Graetz writes “Whether Peringer even partially fulfilled the wish of his king is not known; probably he altogether failed in his mission.” Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (CB, Berlin, 1852-60), cols. 270 no. 1876.

[20] Graetz, History of the Jews V, pp. 182-83; Steinschneider, CB, col. 270 no. 1876.

[21] Christian Hebraism: The Study of Jewish Culture by Christian Scholars in Medieval and Early Modern Times, (Cambridge, Mass., 1986), p. 40 no. 61.[22] The Jewish Life of Christ being the SEPHER TOLDOTH JESHU, or Book of the Generation of Jesus, translated by G. W. Foote and J. M. Wheeler (2018), p. 6.

[23] “Wagenseil’s Latin Introductory Material to His Tela Ignea Satanae (The Fiery Darts of Satan) Published in 1681,, Translated into English” Translated by Wade Blocker (wblocker@nmol.com) Dates of Translation: 2000-12-21 through 2001-03-09.

[24] Malkiel,, pp. 126, 136; Manuel, The Broken Staff, pp. 76, 150-51.

[25] Toledot Jeshu, for all its condemnation in Christian sources, is also not well received by Jewish chroniclers. Graetz, vol. v pp. 185-86, describes it as an “insipid compilation of the magical miracles of Jesus (Toldoth Jesho) with which a Jew, who had been persecuted by Christians, tried to revenge himself on the founder of Christianity.” Manuel, p. 150, in even stronger language, describes it as “the most scandalous of all” of the works in Tela ignea Satanae, “a scurrilous account . . . a gross parody that outraged Christians.”

[26] J. D. Eisenstein, ed., Otzar Vikkuhim (Israel, 1969), pp. 82-86 [Hebrew Mordechai Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel III, (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols. 843-85 [Hebrew].

[27] Gershon David Hundert, Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, (New Haven & London, 2008) p. 1906; Isaac ben Abraham Troki, Hizzuk Emunah or Faith Strengthened, translated by Moses Mocatta, introduction by Trude Weiss-Rosmarin (New York, 1970), v-xii.

[28] Peter Schäfer, Jesus in the Talmud (Princeton, 2007), pp. 3-4.

[29] Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (Chain of Tradition), a popular and much reprinted mixture of history and tales, is a chronicle of Jewish history from the creation to the time of the author. Parenthetically, the work was completed on the day of the bar mitzvah of ibn Yahya’s eldest son, his first born, Joseph, to whom the book is addressed.

[30] Gotthard Deutsch, S. Mannheimer, “Brenz, Samuel Friedrich,” Jewish Encyclopedia, Isadore Singer, ed. V. 3 (New York, 1901-06), p. 370; Carlebach, Divided Souls, p. 90.

[31] The title-page gives the place of printing in Hebrew as Hanau, 1615, based on the Hebrew text, שלמ”ה (375 = 1615) and right below the Hebrew, in Latin letters, is Altdorf MDCLXXX (1680). This title page is than a copy of the original with the place and date of the second edition noted below the Hebrew. Der Jüdische Theriak was translated into Latin by J. Wülder (Wilfer, 1681) and reprinted again in 1737 by Zusssman ben Isaac Roedelsheim who, according to Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature, translated by Bernard Martin, IV (New York, 1975), p. 165, further Yiddishized the language of the work somewhat, and in places changed purely German wiods into more Yiddish teems.” Der Jüdische Theriak was translated into English by Morris M. Faierstein as Yudisher Theriak: An Early Modern Yiddish Defense of Judaism (Detroit, 2016).

[32] After writing the above my supposition found support in Faierstein’s introduction (p. 27) where he writes “The work would be useful to Christian Hebraists and help them to formulate counter arguments to the Jewish objections raised by Zalman Zevi against the missionary works that were being produced with the intention of convincing Jews to convert to Christianity.”

[33] Zinberg, pp. 165-66.

[34] Faierstein, p. ix- xi.

[35] Zinberg, p. 166, quoting Der Jüdische Theriak.

[36] Faierstein, p. 38.

[37] Waxman, II pp. 557-59; Zinberg, p. 166, quoting Der Jüdische Theriak.

[38] Carlebach, Divided Souls, p. 185.

[39] Faierstein, pp. 140, 144.

[40] Concerning the diminished interest by Christian-Hebraists in rabbinic literature and studies in the eighteenth century see Elisheva Carlebach, “The Status of the Talmud in Early Modern Europe” in Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein, eds. Sharon Lieberman Mintz and Gabriel M. Goldstein, (New York: Yeshiva Univ. Museum, 2005), pp.85-88 and Jam-Win Wesselius, “The First Talmud Translation into Dutch: Jacob Fundam’s Schatkamer der Talmud (1737),” Studia Rosenthaliana 33:1 (1999), p. 60.

One thought on “Hebrew printing in Altdorf: A brief Christian-Hebraist Phenomenon”

Many thanks to Marvin Heller for highlighting the print activity in Altdorf near Nürnberg.

It is worth pointing out that some prints carry the place of printing as Altdorfii Noricorum (i.a. Altdorf near Nürnberg), whereas other bring Norimbergae & Altdorffii (i.a. Nürnberg and Altdorf). According to J Benzing , Die Buchdrucker des 16. Und 17. Jahrhunderts, Wiesbaden 1982, a number of Nürnberg printers also had branches in Altdorf. This probably means, that we cannot be absolutely sure of the actual location of the print shop for some of the books discussed.

Over the years, I have collected over 80 titles for books coming from the Altdorf press , dealing with Jewish subjects. From the year 1700 onwards, I record I record some 180 titles.

Two minor points need to be mentioned. R. Yomtov Lipman Muhlhausen most like did not stem from the town M. in Alsace as stated, I believe his origin to be of the town with the same name, located 30 miles north east of Erfurt. The manuscript of the Nizzachon was taken from the Rav of Schnaittach (not Schnattach).

The copper etching of the person wearing Tefilin in the Sota edition 1680, was copied a number of times and was even ascribed to Rav Shaul Morteira in the Warsaw 1912 (?) edition of Givat Shaul

Moshe N. Rosenfeld, London