Deciphering the Talmud: The First English Edition of the Talmud Revisited. Michael Levi Rodkinson: His Translation of the Talmud, and the Ensuing Controversy

In honor of the publication of Marvin J. Heller’s new

book, Further Studies in the Making

of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden, 2013), the Seforim Blog is happy to

present this abridgment of chapter 13.

book, Further Studies in the Making

of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden, 2013), the Seforim Blog is happy to

present this abridgment of chapter 13.

Deciphering the Talmud: The

First English Edition of the Talmud Revisited.

First English Edition of the Talmud Revisited.

Michael Levi Rodkinson: His Translation of

the Talmud, and the Ensuing Controversy

the Talmud, and the Ensuing Controversy

Marvin J. Heller

The Talmud, the quintessential Jewish book, is a

challenging work. A source of Bible

interpretation, halakhah, ethical values, and ontology, often described as a

sea, it is a comprehensive work that encompasses all aspects of human endeavor.

Rabbinic Judaism is inconceivable

without the Talmud. Jewish students

traditionally followed an educational path beginning in early childhood that

culminated in Talmud study, an activity that continued for the remainder of the

adult male’s life.

challenging work. A source of Bible

interpretation, halakhah, ethical values, and ontology, often described as a

sea, it is a comprehensive work that encompasses all aspects of human endeavor.

Rabbinic Judaism is inconceivable

without the Talmud. Jewish students

traditionally followed an educational path beginning in early childhood that

culminated in Talmud study, an activity that continued for the remainder of the

adult male’s life.

That path was never easy. The Talmud is a complex and demanding work, its complexity

compounded by the fact that it is, to a large extent, written in Aramaic, the

language of the Jews in the Babylonian exile, spoken in the Middle East for a

millennium, and used in the redaction of the Talmud. Jews living outside of the Middle East, and even there after

Aramaic ceased to be a spoken language, found approaching the Talmud a daunting

task. Talmud study was, for many,

excepting scholars steeped in Talmudic literature, a difficult undertaking,

made all the more so by its language and structure. After the Enlightenment, when large numbers of Jews received less

intensive Jewish educations, these impediments to Talmud study became more prevalent.

compounded by the fact that it is, to a large extent, written in Aramaic, the

language of the Jews in the Babylonian exile, spoken in the Middle East for a

millennium, and used in the redaction of the Talmud. Jews living outside of the Middle East, and even there after

Aramaic ceased to be a spoken language, found approaching the Talmud a daunting

task. Talmud study was, for many,

excepting scholars steeped in Talmudic literature, a difficult undertaking,

made all the more so by its language and structure. After the Enlightenment, when large numbers of Jews received less

intensive Jewish educations, these impediments to Talmud study became more prevalent.

Elucidation of the text was accomplished through

commentaries, most notably that of R. Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi,

1040-1105). Within his commentary there

are numerous instances in which Rashi explains a term in medieval French, his

vernacular. In the modern period,

another solution to the language problem presented itself for those who

required more than the explanation of difficult terms, that is, the translation

of the text of the Talmud into the vernacular.

commentaries, most notably that of R. Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi,

1040-1105). Within his commentary there

are numerous instances in which Rashi explains a term in medieval French, his

vernacular. In the modern period,

another solution to the language problem presented itself for those who

required more than the explanation of difficult terms, that is, the translation

of the text of the Talmud into the vernacular.

There have

been several such translations of Mishnayot and parts of or entire tractates

beginning in the sixteenth century. It was not, however, until 1891 that a complete Talmudic tractate

was translated into English. In that year, the Rev. A. W. Streane, “Fellow and

Divinity and Hebrew Lecturer, of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and

Formerly Tyrwhitt’s Hebrew Scholar,” published an English edition of tractate Hagigah. A

scholarly work, the translation, in 124 pages, is accompanied by marginal

references to biblical passages and, at the bottom of the page, notes. The

volume concludes with a glossary, indexes of biblical quotations, persons and

places, Hebrew words, and a general index.

been several such translations of Mishnayot and parts of or entire tractates

beginning in the sixteenth century. It was not, however, until 1891 that a complete Talmudic tractate

was translated into English. In that year, the Rev. A. W. Streane, “Fellow and

Divinity and Hebrew Lecturer, of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and

Formerly Tyrwhitt’s Hebrew Scholar,” published an English edition of tractate Hagigah. A

scholarly work, the translation, in 124 pages, is accompanied by marginal

references to biblical passages and, at the bottom of the page, notes. The

volume concludes with a glossary, indexes of biblical quotations, persons and

places, Hebrew words, and a general index.

All that was available in English from the Talmud in

the last decade of the nineteenth century were fragmentary portions of

tractates, Mishnaic treatises, and Streane’s translation of Hagigah. At that time an effort was begun to

translate a substantial portion of the Talmud into English. The subject of this

paper is that pioneer effort to produce an English edition of the Talmud. This paper addresses the background of that

translation, the manner in which it was undertaken, and its reception. It is also concerned with the translator’s

motivation and his qualifications for undertaking such an ambitious

project. The paper does not, however, critique

the translation, that having been done, and done well, as we shall see, in

contemporary appraisals of the first

English Talmud.

the last decade of the nineteenth century were fragmentary portions of

tractates, Mishnaic treatises, and Streane’s translation of Hagigah. At that time an effort was begun to

translate a substantial portion of the Talmud into English. The subject of this

paper is that pioneer effort to produce an English edition of the Talmud. This paper addresses the background of that

translation, the manner in which it was undertaken, and its reception. It is also concerned with the translator’s

motivation and his qualifications for undertaking such an ambitious

project. The paper does not, however, critique

the translation, that having been done, and done well, as we shall see, in

contemporary appraisals of the first

English Talmud.

The effort to provide English speakers with a Talmud

was undertaken by Michael Levi Rodkinson (1845-1904), whose background and

outlook made him an unlikely aspirant for such a project. Rodkinson, a radical proponent of haskalah,

proposed to translate the entire Talmud, not only to making it accessible to

English speakers, but also to transform that “chaotic” work, through careful

editing, into “a readable, intelligible work.”

was undertaken by Michael Levi Rodkinson (1845-1904), whose background and

outlook made him an unlikely aspirant for such a project. Rodkinson, a radical proponent of haskalah,

proposed to translate the entire Talmud, not only to making it accessible to

English speakers, but also to transform that “chaotic” work, through careful

editing, into “a readable, intelligible work.”

Rodkinson is a fascinating figure, albeit a thorough

scoundrel. He was born to a

distinguished Hasidic family; his father was Sender (Alexander) Frumkin (1799-1876)

of Shklov, his mother, Radka Hayyah Horowitz (1802-47). Radka died when Rodkinson was an infant, and

he later changed his surname from Frumkin to Rodkinson, that is, Radka’s

son. Some time after, perhaps in his

early twenties, Rodkinson became a maskil, with the result that his

literary oeuvre encompasses both Hasidic and maskilic works. Rodkinson’s personal life was disreputable,

his peccadilloes including bigamy and other affairs with women. Subsequently, Rodkinson worked in St.

Petersburg as a stock broker and speculator, and sold forged documents, such as

military exemptions and travel papers. For these latter offenses Rodkinson was sentenced to a year in prison,

three years loss of honor, and fined 1,800 rubles. To avoid these penalties, Rodkinson fled to Königsberg, Prussia.

scoundrel. He was born to a

distinguished Hasidic family; his father was Sender (Alexander) Frumkin (1799-1876)

of Shklov, his mother, Radka Hayyah Horowitz (1802-47). Radka died when Rodkinson was an infant, and

he later changed his surname from Frumkin to Rodkinson, that is, Radka’s

son. Some time after, perhaps in his

early twenties, Rodkinson became a maskil, with the result that his

literary oeuvre encompasses both Hasidic and maskilic works. Rodkinson’s personal life was disreputable,

his peccadilloes including bigamy and other affairs with women. Subsequently, Rodkinson worked in St.

Petersburg as a stock broker and speculator, and sold forged documents, such as

military exemptions and travel papers. For these latter offenses Rodkinson was sentenced to a year in prison,

three years loss of honor, and fined 1,800 rubles. To avoid these penalties, Rodkinson fled to Königsberg, Prussia.

In Königsberg Rodkinson edited a journal, the Hebrew

weekly, ha-Kol (1876-c.1880), described as representing the “radical and

militant tendency of the Haskalah.” He

was also the author of a number of monographs on various Jewish subjects,

purporting to explain Jewish religious and ritual practice, although certainly

not from a traditional perspective. The

antagonism engendered by these monographs was intensified by his personality, arousing such hostility, that,

together with his ongoing legal entanglements, Rodkinson, in 1889, found it

advisable to emigrate to the United States.

weekly, ha-Kol (1876-c.1880), described as representing the “radical and

militant tendency of the Haskalah.” He

was also the author of a number of monographs on various Jewish subjects,

purporting to explain Jewish religious and ritual practice, although certainly

not from a traditional perspective. The

antagonism engendered by these monographs was intensified by his personality, arousing such hostility, that,

together with his ongoing legal entanglements, Rodkinson, in 1889, found it

advisable to emigrate to the United States.

That Rodkinson should have left the Hasidic fold, become

a maskil, and adhered to a radical ideology is not that unusual. The

late nineteenth century was witness to the assimilation or casting off of

tradition by large numbers of Jews.

However, that someone of Rodkinson’s outlook should undertake to translate

the Talmud into English is certainly unusual and perhaps even unique. There is, than, a contradiction between his enlightenment

attitudes and personality, and his attempts, through his abridgement and

translation, to spread Talmudic studies.

Individual maskilim might, as an intellectual endeavor, continue

to study Talmud, but none devoted any effort or energy to bringing the Talmud

to a public that had largely distanced itself from that repository of Jewish

knowledge.

a maskil, and adhered to a radical ideology is not that unusual. The

late nineteenth century was witness to the assimilation or casting off of

tradition by large numbers of Jews.

However, that someone of Rodkinson’s outlook should undertake to translate

the Talmud into English is certainly unusual and perhaps even unique. There is, than, a contradiction between his enlightenment

attitudes and personality, and his attempts, through his abridgement and

translation, to spread Talmudic studies.

Individual maskilim might, as an intellectual endeavor, continue

to study Talmud, but none devoted any effort or energy to bringing the Talmud

to a public that had largely distanced itself from that repository of Jewish

knowledge.

Nevertheless, Rodkinson’s goal of translating the

Talmud had been, as we are informed in the introduction to Rosh Hashana (sample

volume), his dream for twelve years. He

had expressed a “desire to revise and correct the Talmud” as early as 1882 in le-Boker

Mishpat, and subsequently in Iggorot Petuhot and Iggorot

ha-Talmud (Pressburg, 1885); and Ha-Kol (nos. 298, 299, and 300). In Iggorot Petuhot (repeated in the

Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana) Rodkinson describes the incredible

multiplicity of rabbinic works since the redaction of the Talmud. He notes the numerous responsa, which, their

great number notwithstanding, have not resolved anything. The Talmudic page is confused and unclear,

due to its many commentaries and cross-references. Rodkinson states that previous exegetes, such as the Vilna Gaon,

R. Akiva Egger, R. Pick, and others, rather than clarifying the page,

proliferated works that were printed with the Talmud, adding to the confusion.

It is Rodkinson’s intent to remove the shame of the Talmud from Israel and

restore the Talmud to its original state.

Thought of this project gives him no rest. He thinks of it day and night.

He writes, towards the end of Iggorot Petuhot that he will “offer

and dedicate the remainder of his days on the altar of this work, it will be

the delight of his nights and with it he will complete the hours of the

day. . . . it will give purpose to his

life.”

Talmud had been, as we are informed in the introduction to Rosh Hashana (sample

volume), his dream for twelve years. He

had expressed a “desire to revise and correct the Talmud” as early as 1882 in le-Boker

Mishpat, and subsequently in Iggorot Petuhot and Iggorot

ha-Talmud (Pressburg, 1885); and Ha-Kol (nos. 298, 299, and 300). In Iggorot Petuhot (repeated in the

Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana) Rodkinson describes the incredible

multiplicity of rabbinic works since the redaction of the Talmud. He notes the numerous responsa, which, their

great number notwithstanding, have not resolved anything. The Talmudic page is confused and unclear,

due to its many commentaries and cross-references. Rodkinson states that previous exegetes, such as the Vilna Gaon,

R. Akiva Egger, R. Pick, and others, rather than clarifying the page,

proliferated works that were printed with the Talmud, adding to the confusion.

It is Rodkinson’s intent to remove the shame of the Talmud from Israel and

restore the Talmud to its original state.

Thought of this project gives him no rest. He thinks of it day and night.

He writes, towards the end of Iggorot Petuhot that he will “offer

and dedicate the remainder of his days on the altar of this work, it will be

the delight of his nights and with it he will complete the hours of the

day. . . . it will give purpose to his

life.”

Perhaps Rodkinson’s motivation can be found in the

criticism leveled by his opponents, that intellectually, Rodkinson’s weltanschauung

was bifurcated, that is, he suffered from a conflict between his Hasidic past

and radical present. Joseph Kohen-Zedek

(1827-1903), author of Sefat Emet, a work harshly critical of Rodkinson,

accused him of being “androgynous,” two-faced, “one time he shows his face as a

Hasid, the next as a heretic, and should therefore be called Sama’el instead of

Michael, for he is a destructive angel.”[1] More recently, Joseph Dan, writing about

Rodkinson’s Hasidic stories, notes that “Michael Ha-Levi-Frumkin Rodkinson is unique

in that he was neither a real Hasid nor a real Maskil, . . .”[2] Abridging, editing, translating, and, most

importantly, modernizing the Talmud may have been, for Rodkinson, a means of

reconciling these diverse worlds. The

rationale for the abridged translation, “a work that cannot prove financially

profitable, and that will probably be productive of much adverse criticism in

certain quarters,” is set forth in the English preamble, “A Few Words to the

English Reader,” to Rosh Hashana,

criticism leveled by his opponents, that intellectually, Rodkinson’s weltanschauung

was bifurcated, that is, he suffered from a conflict between his Hasidic past

and radical present. Joseph Kohen-Zedek

(1827-1903), author of Sefat Emet, a work harshly critical of Rodkinson,

accused him of being “androgynous,” two-faced, “one time he shows his face as a

Hasid, the next as a heretic, and should therefore be called Sama’el instead of

Michael, for he is a destructive angel.”[1] More recently, Joseph Dan, writing about

Rodkinson’s Hasidic stories, notes that “Michael Ha-Levi-Frumkin Rodkinson is unique

in that he was neither a real Hasid nor a real Maskil, . . .”[2] Abridging, editing, translating, and, most

importantly, modernizing the Talmud may have been, for Rodkinson, a means of

reconciling these diverse worlds. The

rationale for the abridged translation, “a work that cannot prove financially

profitable, and that will probably be productive of much adverse criticism in

certain quarters,” is set forth in the English preamble, “A Few Words to the

English Reader,” to Rosh Hashana,

Since the time of Moses Mendelssohn the Jew has made

vast strides forward. There is to-day

no branch of Human activity in which his influence is not felt. Interesting himself in the affairs of the

world, he has been enabled to bring a degree of intelligence and industry to

bear upon modern life, that has challenged the admiration of the modern

world. But with the Talmud, it is not

so. That vast encyclopedia of Jewish

lore remains as it was. No improvement

has been possible; no progress has been made with it. Reprint after reprint has appeared, but it has always been called

the Talmud Babli, as chaotic as when its canon was originally appointed. Commentary upon commentary has appeared yet

the text of the Talmud has not received that heroic treatment that will alone

enable us to say that the Talmud has been improved.[3]

vast strides forward. There is to-day

no branch of Human activity in which his influence is not felt. Interesting himself in the affairs of the

world, he has been enabled to bring a degree of intelligence and industry to

bear upon modern life, that has challenged the admiration of the modern

world. But with the Talmud, it is not

so. That vast encyclopedia of Jewish

lore remains as it was. No improvement

has been possible; no progress has been made with it. Reprint after reprint has appeared, but it has always been called

the Talmud Babli, as chaotic as when its canon was originally appointed. Commentary upon commentary has appeared yet

the text of the Talmud has not received that heroic treatment that will alone

enable us to say that the Talmud has been improved.[3]

Despite the “venomous vituperation” of the attacks

upon it, a more intimate knowledge of that work would demonstrate that the

Talmud “is a work of the greatest sympathies, the most liberal impulses, and

the widest humanitarianism.” Many of

the phrases for which the Talmud is attacked were not part of that work, but

rather “are the latter additions of enemies and ignoramuses.” How did its present situation come about?

upon it, a more intimate knowledge of that work would demonstrate that the

Talmud “is a work of the greatest sympathies, the most liberal impulses, and

the widest humanitarianism.” Many of

the phrases for which the Talmud is attacked were not part of that work, but

rather “are the latter additions of enemies and ignoramuses.” How did its present situation come about?

When it is remembered that until it was first printed,

that before the canon of the Talmud was fixed in the sixth century, it had been

growing for more than six hundred years (the Talmud was in manuscript for eight

centuries), that during the whole of that time it was beset by ignorant, unrelenting

and bitter foes, that marginal notes were easily added and in after years

easily embodied in the text by unintelligent printers, such a theory as here

advanced is not at all improbable.[4]

that before the canon of the Talmud was fixed in the sixth century, it had been

growing for more than six hundred years (the Talmud was in manuscript for eight

centuries), that during the whole of that time it was beset by ignorant, unrelenting

and bitter foes, that marginal notes were easily added and in after years

easily embodied in the text by unintelligent printers, such a theory as here

advanced is not at all improbable.[4]

Rodkinson rises to the defense of the Talmud, a work

that he feels will be remembered when the Shulkhan Arukh is forgotten,

concluding that the best defense is to allow it to “plead its own cause in a

modern language.” Others have attempted

to translate it, for example, Pinner and Rawicz, but their attempts were

neither correct not readable, precisely because they were only translations.

that he feels will be remembered when the Shulkhan Arukh is forgotten,

concluding that the best defense is to allow it to “plead its own cause in a

modern language.” Others have attempted

to translate it, for example, Pinner and Rawicz, but their attempts were

neither correct not readable, precisely because they were only translations.

If it were translated from the original text one would

not see the forest for the trees. . . . As it stands in the original it is,

therefore, a tangled mass defying reproductions in a modern tongue. It has consequently occurred to us that in

order to enable the Talmud to open its mouth, the text must be carefully

edited. A modern book, constructed on a

supposed scientific plan, we cannot make of it, for that would not be the Talmud;

but a readable, intelligible work it can be made. We have, therefore, carefully punctuated the Hebrew text with

modern punctuation marks, and have re-edited it by omitting all such irrelevant

matter as interrupted the clear and orderly arrangement of the various

arguments. In this way disappears those

unnecessary debates within debates, which only serve to confuse and never to

enlighten on the question debated. . . .[5]

not see the forest for the trees. . . . As it stands in the original it is,

therefore, a tangled mass defying reproductions in a modern tongue. It has consequently occurred to us that in

order to enable the Talmud to open its mouth, the text must be carefully

edited. A modern book, constructed on a

supposed scientific plan, we cannot make of it, for that would not be the Talmud;

but a readable, intelligible work it can be made. We have, therefore, carefully punctuated the Hebrew text with

modern punctuation marks, and have re-edited it by omitting all such irrelevant

matter as interrupted the clear and orderly arrangement of the various

arguments. In this way disappears those

unnecessary debates within debates, which only serve to confuse and never to

enlighten on the question debated. . . .[5]

In the Hebrew introduction Rodkinson writes that the

task of restoring the original, or core Talmud should properly be done by a

gathering of great sages. However,

there are none today who wish to undertake such a great and burdensome

task. If he would seek their

assistance, it would take years to arrive at some unity of purpose, and if this

was accomplished, it would take yet more years before anything was done, for

they are occupied with other matters.

Furthermore, the rabbinic figures appropriate for this undertaking are a

minority of a minority, for “this work is not a matter of wisdom but of

action.”[6]

Therefore, the project only

requires men who know the language and style of the Talmud, a sharp eye and

ear, who can distinguish between its various parts and contents. Such men need not have learned in a bet

medrash (rabbinic house of study) or have earned the titles of professor or

doctor, nor know Latin or Greek.

task of restoring the original, or core Talmud should properly be done by a

gathering of great sages. However,

there are none today who wish to undertake such a great and burdensome

task. If he would seek their

assistance, it would take years to arrive at some unity of purpose, and if this

was accomplished, it would take yet more years before anything was done, for

they are occupied with other matters.

Furthermore, the rabbinic figures appropriate for this undertaking are a

minority of a minority, for “this work is not a matter of wisdom but of

action.”[6]

Therefore, the project only

requires men who know the language and style of the Talmud, a sharp eye and

ear, who can distinguish between its various parts and contents. Such men need not have learned in a bet

medrash (rabbinic house of study) or have earned the titles of professor or

doctor, nor know Latin or Greek.

Actual publication of “The New Talmud” began in

stages. In 1895, Tract Rosh Hashana (New

Year) of the New Babylonian Talmud, Edited, Formulated and Punctuated for the

First Time by Michael L. Rodkinson and Translated by Rabbi J. Leonard Levy

. . .” appeared, issued in Philadelphia by Charles Sessler, Publisher. The initial volume, with Hebrew and English

text, has the names of subscribers, Opinions, and a Few Words to the English

Reader from Rodkinson, all repeated in subsequent parts.

stages. In 1895, Tract Rosh Hashana (New

Year) of the New Babylonian Talmud, Edited, Formulated and Punctuated for the

First Time by Michael L. Rodkinson and Translated by Rabbi J. Leonard Levy

. . .” appeared, issued in Philadelphia by Charles Sessler, Publisher. The initial volume, with Hebrew and English

text, has the names of subscribers, Opinions, and a Few Words to the English

Reader from Rodkinson, all repeated in subsequent parts.

That same year, a sample volume, entitled Tract Rosh

Hashana, was published. Despite the fact that the title-page describes it as

tract Rosh Hashana, the volume actually consists of sample pages of Rosh

Hashana (Hebrew), together with sample pages of other tractates, in both

English and Hebrew..

Hashana, was published. Despite the fact that the title-page describes it as

tract Rosh Hashana, the volume actually consists of sample pages of Rosh

Hashana (Hebrew), together with sample pages of other tractates, in both

English and Hebrew..

The title-page of the sample volume (1895) notes that

it is being “edited, formulated and punctuated for the first time by Michael L.

Rodkinson, author of Numerous Theological Works, Formerly Editor of the Hebrew

‘CALL.’” The title-page is followed by subscription information, which may be

submitted to any one of eight individuals.

Next are opinions from prominent personalities and Jewish periodicals,

not all of which can be printed due to space limitations. In only two of these opinions do the writers

state that they have read the advance sheets.

They are Drs. Szold and Mielziner. The former writes that the

Rev. M. L. Rodkinson has “laid before me a number of Hebrew proof sheets of the

treatise ‘Berachoth’ and the whole of the treatise ‘Sabbath’ in manuscript,”

requesting the work to be read critically, and, if it found favor, to “testify

to its merit.” He continues that he has

“very carefully read sixteen chapters of the M.S. of treatise Sabbath and it

affords me the greatest pleasure . . . [that it] is of extraordinary merit and

value. . . .” Dr. Mielziner writes that

he has “perused some advance sheets . . . and finds his [Rodkinson] work to be

very recommendable.”[7] The remaining endorsements are for the

“planned edition,” among them the letters of Prof. Lazarus, of Berlin, and Rev.

Friedman, of Vienna, dated July, 1885, written in response to Rodkinson’s Ha-Kol

articles.

it is being “edited, formulated and punctuated for the first time by Michael L.

Rodkinson, author of Numerous Theological Works, Formerly Editor of the Hebrew

‘CALL.’” The title-page is followed by subscription information, which may be

submitted to any one of eight individuals.

Next are opinions from prominent personalities and Jewish periodicals,

not all of which can be printed due to space limitations. In only two of these opinions do the writers

state that they have read the advance sheets.

They are Drs. Szold and Mielziner. The former writes that the

Rev. M. L. Rodkinson has “laid before me a number of Hebrew proof sheets of the

treatise ‘Berachoth’ and the whole of the treatise ‘Sabbath’ in manuscript,”

requesting the work to be read critically, and, if it found favor, to “testify

to its merit.” He continues that he has

“very carefully read sixteen chapters of the M.S. of treatise Sabbath and it

affords me the greatest pleasure . . . [that it] is of extraordinary merit and

value. . . .” Dr. Mielziner writes that

he has “perused some advance sheets . . . and finds his [Rodkinson] work to be

very recommendable.”[7] The remaining endorsements are for the

“planned edition,” among them the letters of Prof. Lazarus, of Berlin, and Rev.

Friedman, of Vienna, dated July, 1885, written in response to Rodkinson’s Ha-Kol

articles.

The most prominent supporter of the projected translation

was Dr. Isaac Mayer Wise (1819-1900), President of Hebrew Union College (HUC),

and, from 1889 to his death, president of the Central Conference of American

Rabbis. He writes, in a letter dated

January 14, 1895, to an unnamed potential sponsor, “We have the duty to afford

him the opportunity to publish one volume. . . . If this volume is what he

promises, he will be the man to accomplish the task.”[8] The “Opinions” are followed by “A Word to

the Public,” which informs us that

was Dr. Isaac Mayer Wise (1819-1900), President of Hebrew Union College (HUC),

and, from 1889 to his death, president of the Central Conference of American

Rabbis. He writes, in a letter dated

January 14, 1895, to an unnamed potential sponsor, “We have the duty to afford

him the opportunity to publish one volume. . . . If this volume is what he

promises, he will be the man to accomplish the task.”[8] The “Opinions” are followed by “A Word to

the Public,” which informs us that

We have also after 40 years of study and research,

supported by frequent consultations with other like-students, corrected many

errors, discarded much legendary matter, which we have found, are entirely

foreign to the Talmud and its spirit, but have been introduced and “Talmudized”

so to speak, through innumerable reprints, unintentional and intentional errors

. . . and reduced the Babylonian Talmud from more than 5000 to about 1200

pages. . . .

supported by frequent consultations with other like-students, corrected many

errors, discarded much legendary matter, which we have found, are entirely

foreign to the Talmud and its spirit, but have been introduced and “Talmudized”

so to speak, through innumerable reprints, unintentional and intentional errors

. . . and reduced the Babylonian Talmud from more than 5000 to about 1200

pages. . . .

The entire cost of publication for the Hebrew and

English editions will amount to $7500.00 A sum of gigantic proportions

considering our humble means. Yet we

are not the least appalled thereby. . . .[9]

English editions will amount to $7500.00 A sum of gigantic proportions

considering our humble means. Yet we

are not the least appalled thereby. . . .[9]

The sample volume concludes with four specimen pages

in English of Sabbath, Chapter I; two pages, in Hebrew, of tractate Kiddushin,

with Rashi; four pages of sample sheets of “New Year” in English, tractate Rosh

Hashana in Hebrew, with Rashi; a long turgid Hebrew introduction; the

Hebrew opinions; and a second, brief, Hebrew introduction.

in English of Sabbath, Chapter I; two pages, in Hebrew, of tractate Kiddushin,

with Rashi; four pages of sample sheets of “New Year” in English, tractate Rosh

Hashana in Hebrew, with Rashi; a long turgid Hebrew introduction; the

Hebrew opinions; and a second, brief, Hebrew introduction.

The first volumes of “The New Edition of the

Babylonian Talmud” were published in 1896, the last in 1903, followed, that

year, by a supplementary volume on the history of the Talmud.

Babylonian Talmud” were published in 1896, the last in 1903, followed, that

year, by a supplementary volume on the history of the Talmud.

Rodkinson described his approach to translating the

text of the Talmud in the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, and

afterwards, in response to criticism, in an article in Ner Ma’aravi, and

yet again, translated and in abbreviated form, in The History. He claims that “in reality we omit nothing

of importance of the whole text, in the shape given out by its compilers, and

only that which we were certain to have been added by the dislikers of the

Talmud for the purpose of degrading it do we omit.” Omissions fall into seven categories. Repetitions in both halakhah and aggadah are omitted, whether occurring

in several tractates or in only one.

For example, “The discussions in the Gemara are repeated sometimes from

one to fifteen times, some of them without any change at all, and some with

change of little or no importance. In

our edition we give the discussion only once, in its proper place.” Long involved discussions, repeated

elsewhere, are deleted, with only the conclusion being presented and, “Questions

which remain undecided and many of them are not at all practical but only

imaginary, and very peculiar too, we omit.” In some instances Mishnayot are combined. Concerning aggadic material he repeats his

assertion that “any one with common sense, and without partiality, can be found

who would deny that such things were inserted by the Talmud haters only for the

purpose of ridiculing the Talmud. It is

self evident that in our edition such and numerous similar legends do not find

place.”

text of the Talmud in the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, and

afterwards, in response to criticism, in an article in Ner Ma’aravi, and

yet again, translated and in abbreviated form, in The History. He claims that “in reality we omit nothing

of importance of the whole text, in the shape given out by its compilers, and

only that which we were certain to have been added by the dislikers of the

Talmud for the purpose of degrading it do we omit.” Omissions fall into seven categories. Repetitions in both halakhah and aggadah are omitted, whether occurring

in several tractates or in only one.

For example, “The discussions in the Gemara are repeated sometimes from

one to fifteen times, some of them without any change at all, and some with

change of little or no importance. In

our edition we give the discussion only once, in its proper place.” Long involved discussions, repeated

elsewhere, are deleted, with only the conclusion being presented and, “Questions

which remain undecided and many of them are not at all practical but only

imaginary, and very peculiar too, we omit.” In some instances Mishnayot are combined. Concerning aggadic material he repeats his

assertion that “any one with common sense, and without partiality, can be found

who would deny that such things were inserted by the Talmud haters only for the

purpose of ridiculing the Talmud. It is

self evident that in our edition such and numerous similar legends do not find

place.”

The groundwork for the translation, as described in

the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, had been done many years

earlier. Rodkinson, therefore,

concludes that he is able to do “one page of gemara with all of the

commentaries necessary for the work,” without the pilpul, for he has

already read all of it in its entirety, as well as the Jerusalem Talmud, the

Tosefta, and Mishnayot in the winter of 1883-84. Some pages will not even require a full hour, but a half hour

will be sufficient. He feels that he is

capable of learning and understanding five pages of gemara daily that will [then]

be ready for the press, with the result that, by working five hours a day, the

entire project will only take about 550 days.[10]

the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, had been done many years

earlier. Rodkinson, therefore,

concludes that he is able to do “one page of gemara with all of the

commentaries necessary for the work,” without the pilpul, for he has

already read all of it in its entirety, as well as the Jerusalem Talmud, the

Tosefta, and Mishnayot in the winter of 1883-84. Some pages will not even require a full hour, but a half hour

will be sufficient. He feels that he is

capable of learning and understanding five pages of gemara daily that will [then]

be ready for the press, with the result that, by working five hours a day, the

entire project will only take about 550 days.[10]

As noted above, Rosh Hashana was translated by

Rabbi J. Leonard Levy (1865-1917), rabbi of the Reform Congregation Keneseth

Israel, Philadelphia. He had officiated

previously in congregations in England and California, and would later be rabbi

of Congregation Rodeph Shalom, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Levy was the founder of the Philadelphia Sterilized Milk, Ice and Coal

Society, and the author of several books, among them a ten-volume Sunday

Lectures.

Rabbi J. Leonard Levy (1865-1917), rabbi of the Reform Congregation Keneseth

Israel, Philadelphia. He had officiated

previously in congregations in England and California, and would later be rabbi

of Congregation Rodeph Shalom, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Levy was the founder of the Philadelphia Sterilized Milk, Ice and Coal

Society, and the author of several books, among them a ten-volume Sunday

Lectures.

The title-page of the initial

printing of Rosh Hashana (1895) credits Rodkinson with only having “edited,

formulated, and punctuated” the tractate and Levy for having “translated for

the first time from the above text.” There are photographs of Levy and

Rodkinson, and a four-page preface by the former. Levy writes in defense of the Talmud, conservatively and

movingly, without repeating the claims made by Rodkinson. He informs us that he has done the translation

free of charge, for he agrees with the editor that the best defense for the

Talmud is to allow it to speak for itself. He continues that “From my boyhood,

when I sat at the feet of some of the most learned Talmudists in Europe, I

learned to love this wonderful work, this testimony to the mental and spiritual

activities of my ancestors.”[11]

printing of Rosh Hashana (1895) credits Rodkinson with only having “edited,

formulated, and punctuated” the tractate and Levy for having “translated for

the first time from the above text.” There are photographs of Levy and

Rodkinson, and a four-page preface by the former. Levy writes in defense of the Talmud, conservatively and

movingly, without repeating the claims made by Rodkinson. He informs us that he has done the translation

free of charge, for he agrees with the editor that the best defense for the

Talmud is to allow it to speak for itself. He continues that “From my boyhood,

when I sat at the feet of some of the most learned Talmudists in Europe, I

learned to love this wonderful work, this testimony to the mental and spiritual

activities of my ancestors.”[11]

That Levy was the translator of Rosh Hashana

was well known at the time. For

example, the entry for Levy in capsule bibliographies of officiating Rabbis and

Cantors in the United States in the American Jewish Year Book for 5664,

1903-1904, includes among his accomplishments, “Translation of Tractate Rosh

Hashana of the Babylonian Talmud.”[12]

Indeed, Rodkinson thanks Levy in

the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, acknowledging that the

translator, Levy, not only worked without compensation, but also took the time

to go over each and every word with him before it went to press. Nevertheless, Rodkinson writes, there is

absolutely nothing in the translation that he has not verified to the original.[13]

was well known at the time. For

example, the entry for Levy in capsule bibliographies of officiating Rabbis and

Cantors in the United States in the American Jewish Year Book for 5664,

1903-1904, includes among his accomplishments, “Translation of Tractate Rosh

Hashana of the Babylonian Talmud.”[12]

Indeed, Rodkinson thanks Levy in

the Hebrew introduction to Rosh Hashana, acknowledging that the

translator, Levy, not only worked without compensation, but also took the time

to go over each and every word with him before it went to press. Nevertheless, Rodkinson writes, there is

absolutely nothing in the translation that he has not verified to the original.[13]

Levy also translated a portion of the first chapter of

Berakhot, printed in the Atlantic Coast Jewish Annual.[14]

The title-page states “Tract Berakhoth (‘Benedictions’) of the Unabbreviated

Edition of the Babylonian Talmud Translated into English for the first time by

Rabbi J. Leonard Levy . . . Translator of Tract ‘Rosh Hashana’ of the Talmud

Babylonian, etc. etc. To appear in

Quarterly Parts. . . .” Levy’s work

here, apparently, was not meant to be an abridgement, or a restoration of the “original

Talmud.” The English text, from the

beginning of the tractate to the middle of 6a in standard editions, includes

Hebrew phrases and accompanying footnotes.

Berakhot, printed in the Atlantic Coast Jewish Annual.[14]

The title-page states “Tract Berakhoth (‘Benedictions’) of the Unabbreviated

Edition of the Babylonian Talmud Translated into English for the first time by

Rabbi J. Leonard Levy . . . Translator of Tract ‘Rosh Hashana’ of the Talmud

Babylonian, etc. etc. To appear in

Quarterly Parts. . . .” Levy’s work

here, apparently, was not meant to be an abridgement, or a restoration of the “original

Talmud.” The English text, from the

beginning of the tractate to the middle of 6a in standard editions, includes

Hebrew phrases and accompanying footnotes.

The title-pages to the “New Edition of the Talmud”

state that they were translated into English by Michael L. Rodkinson. No other translator or collaborator is

mentioned, nor is anyone else credited with such a role in the History of

the Talmud. We have already seen

that in the sample volume, Rodkinson’s role is defined as editing, formulating

and punctuating. The Prospectus informs

us that “The Rev. Dr. Grossman of Detroit will undertake ‘Yumah,’ and the Rev.

Dr. Stoltz, of Chicago, ‘Moed Katan,’” and that other tractates will be revised

by “competent authorities of English diction,” and the translation of Rosh Hashana

was done by Rabbi Levy. However, by the

time that the New Talmud was being sold to the public the only name mentioned,

and as translator at that, is Rodkinson.

While some commentators mention that other hands are visible in the

work, none of the rabbinic figures associated with the translation seem to have

objected to Rodkinson’s omission of their names. Perhaps this may be attributed, as we shall see, to the responses

to the New Talmud and, most likely, a wish by the more prominent translators,

to distance themselves from it.

state that they were translated into English by Michael L. Rodkinson. No other translator or collaborator is

mentioned, nor is anyone else credited with such a role in the History of

the Talmud. We have already seen

that in the sample volume, Rodkinson’s role is defined as editing, formulating

and punctuating. The Prospectus informs

us that “The Rev. Dr. Grossman of Detroit will undertake ‘Yumah,’ and the Rev.

Dr. Stoltz, of Chicago, ‘Moed Katan,’” and that other tractates will be revised

by “competent authorities of English diction,” and the translation of Rosh Hashana

was done by Rabbi Levy. However, by the

time that the New Talmud was being sold to the public the only name mentioned,

and as translator at that, is Rodkinson.

While some commentators mention that other hands are visible in the

work, none of the rabbinic figures associated with the translation seem to have

objected to Rodkinson’s omission of their names. Perhaps this may be attributed, as we shall see, to the responses

to the New Talmud and, most likely, a wish by the more prominent translators,

to distance themselves from it.

How did Rodkinson justify this? In the introduction to Rosh Hashana

he remarks that books are not called by the names of multiple authors, but

rather by one writer, for example, the redactors of the Talmud, Ravina and Rav

Ashi.[15] How then, and by whom was the translation

done? Morris Vinchevsky, who wrote for ha-Kol

for two years, from 1877 through 1878, and was, during that time, a frequent

guest in the Rodkinson home, describes Rodkinson as being driven to translate

the Talmud into English, even though

he remarks that books are not called by the names of multiple authors, but

rather by one writer, for example, the redactors of the Talmud, Ravina and Rav

Ashi.[15] How then, and by whom was the translation

done? Morris Vinchevsky, who wrote for ha-Kol

for two years, from 1877 through 1878, and was, during that time, a frequent

guest in the Rodkinson home, describes Rodkinson as being driven to translate

the Talmud into English, even though

he did not know a hundred English expressions. How did he do the translation? Through

‘exploitation’ of indigent young men, with the help of his son (partially), and

the assistance of others. The principle

was the translation. Whether the

translations were good or bad – let the forest judge, as Shakespear says (As

You Like It). Rodkinson was never

pedantic. Whether earlier or later, for

better or worse, between impure or pure, never mattered. Not because he was undisciplined and

anarchic, but because he was preoccupied all his days and involved with matters

that were not within his power. For

that reason he was not careful about the cleanliness of his teeth, and perhaps

if he had, in his later years, false teeth, he would have carried them in his

pocket, as did the late Imber, owner of ha-Tikva, in his time.[16]

‘exploitation’ of indigent young men, with the help of his son (partially), and

the assistance of others. The principle

was the translation. Whether the

translations were good or bad – let the forest judge, as Shakespear says (As

You Like It). Rodkinson was never

pedantic. Whether earlier or later, for

better or worse, between impure or pure, never mattered. Not because he was undisciplined and

anarchic, but because he was preoccupied all his days and involved with matters

that were not within his power. For

that reason he was not careful about the cleanliness of his teeth, and perhaps

if he had, in his later years, false teeth, he would have carried them in his

pocket, as did the late Imber, owner of ha-Tikva, in his time.[16]

An example of Rodkinson’s difficulty with English can

be seen from the title-page of the sample volume issued in 1895, which refers

to him as, “Formerly Editor of the Hebrew ‘CALL,’” that is, ha-Kol. The translation of ha-Kol, correctly

rendered on his German title-pages as Der Stimme, is “The Voice”, not

“CALL.” The family has confirmed that

Rodkinson was not fluent in English.

Who then, did translate the Talmud into English for Rodkinson? According

to Vinchevsky, the work was done by the “‘exploitation’ of indigent young men”

whom Deinard reports were paid eight dollars a week for their work.[17] A fuller description is given by Judah D.

Eisenstein (1854-1956), who writes that, not understanding the English

language, Rodkinson employed Jewish high school students. He translated the Talmud into Yiddish for

them, and they than translated it into English. After they had worked for him for a short time, Rodkinson,

claiming their translation was unsatisfactory, dismissed them without

payment. He then hired more young men,

repeating the process.[18]

be seen from the title-page of the sample volume issued in 1895, which refers

to him as, “Formerly Editor of the Hebrew ‘CALL,’” that is, ha-Kol. The translation of ha-Kol, correctly

rendered on his German title-pages as Der Stimme, is “The Voice”, not

“CALL.” The family has confirmed that

Rodkinson was not fluent in English.

Who then, did translate the Talmud into English for Rodkinson? According

to Vinchevsky, the work was done by the “‘exploitation’ of indigent young men”

whom Deinard reports were paid eight dollars a week for their work.[17] A fuller description is given by Judah D.

Eisenstein (1854-1956), who writes that, not understanding the English

language, Rodkinson employed Jewish high school students. He translated the Talmud into Yiddish for

them, and they than translated it into English. After they had worked for him for a short time, Rodkinson,

claiming their translation was unsatisfactory, dismissed them without

payment. He then hired more young men,

repeating the process.[18]

A considerable

part of the work appears to have been done by family members. Mention is made, in the Prospectus, of

Rodkinson’s son Norbert. Credit is also

due, based on the family’s oral tradition, to Rosamund, Rodkinson’s daughter

from his first marriage, who was his secretary and researcher. Yet another family member who assisted him

was his nephew Abraham Frumkin.

Rodkinson also made use of dictionaries, enabling him to also work on

the translation. Nahum Sokolow

describes the process in a kinder fashion.

“He didn’t know English – but his son did. This would have deterred someone else, but not him. This elderly man began to learn English, and

translated together with his son. When

there were errors in the first volumes, they worked further to correct those

errors. A man such as this is a living

melodrama.”[19]

part of the work appears to have been done by family members. Mention is made, in the Prospectus, of

Rodkinson’s son Norbert. Credit is also

due, based on the family’s oral tradition, to Rosamund, Rodkinson’s daughter

from his first marriage, who was his secretary and researcher. Yet another family member who assisted him

was his nephew Abraham Frumkin.

Rodkinson also made use of dictionaries, enabling him to also work on

the translation. Nahum Sokolow

describes the process in a kinder fashion.

“He didn’t know English – but his son did. This would have deterred someone else, but not him. This elderly man began to learn English, and

translated together with his son. When

there were errors in the first volumes, they worked further to correct those

errors. A man such as this is a living

melodrama.”[19]

There is a disquieting note to all of this. It is clear from the above that many of

Rodkinson’s contemporaries knew that his English was insufficient for the

undertaking. Nevertheless, Isaac Mayer

Wise, referring to Rodkinson’s proposed translation, wrote “he will be the man

to accomplish the task,” unless he meant in the role of editor, still a

daunting venture for someone not proficient in English. Afterwards, Rodkinson was credited with

translating a difficult, complex work, written in Hebrew and Aramaic, into a

language that, if not foreign to him, was one in which he lacked literary

competence. Some reviewers did comment

on the work of translating. Kaufmann

Kohler, for example, wrote in his review, “there are different hands easily

discerned in the book,” and refers to Rodkinson as the editor. Nevertheless, most reviewers accepted him as

the translator, and he is remembered for that achievement today.

Rodkinson’s contemporaries knew that his English was insufficient for the

undertaking. Nevertheless, Isaac Mayer

Wise, referring to Rodkinson’s proposed translation, wrote “he will be the man

to accomplish the task,” unless he meant in the role of editor, still a

daunting venture for someone not proficient in English. Afterwards, Rodkinson was credited with

translating a difficult, complex work, written in Hebrew and Aramaic, into a

language that, if not foreign to him, was one in which he lacked literary

competence. Some reviewers did comment

on the work of translating. Kaufmann

Kohler, for example, wrote in his review, “there are different hands easily

discerned in the book,” and refers to Rodkinson as the editor. Nevertheless, most reviewers accepted him as

the translator, and he is remembered for that achievement today.

Rosh Hashana

and Shekalim were quickly followed by Shabbat, in two parts. Printed with Shabbat is a letter,

dated March 24, 1896, from the revisor, Dr. Wise, to the New Amsterdam Book

Company, and three introductory pieces by Rodkinson. Wise writes:

and Shekalim were quickly followed by Shabbat, in two parts. Printed with Shabbat is a letter,

dated March 24, 1896, from the revisor, Dr. Wise, to the New Amsterdam Book

Company, and three introductory pieces by Rodkinson. Wise writes:

I beg leave to testify herewith that I have carefully

read and revised the English translation of this volume of the “Tract Sabbath,”

Rodkinson’s reconstruction of the original text of the Talmud. The translation is correct, almost literal,

where the English idiom permitted it.[20]

read and revised the English translation of this volume of the “Tract Sabbath,”

Rodkinson’s reconstruction of the original text of the Talmud. The translation is correct, almost literal,

where the English idiom permitted it.[20]

The first of Rodkinson’s pieces, the Editor’s Preface,

is the “A few Words to the English Reader” printed with Rosh Hashana,

slightly modified, with new concluding paragraphs. Rodkinson writes that he is open to criticism that is objective

and will “gladly avail ourselves of suggestions given to us, but we shall

continue to disregard all personal criticism directed not against our work but

against its author. This may serve as a

reply to a so-called review which appeared in one of our Western

weeklies.” He concludes with heartfelt

thanks to Dr. Wise for “several evenings spent in revising this volume and for

many courtesies extended to us in general.”

This is followed by a “Brief General Introduction to the Babylonian

Talmud,” where Rodkinson restates his opinion as to what has brought the Talmud

to its present condition:

is the “A few Words to the English Reader” printed with Rosh Hashana,

slightly modified, with new concluding paragraphs. Rodkinson writes that he is open to criticism that is objective

and will “gladly avail ourselves of suggestions given to us, but we shall

continue to disregard all personal criticism directed not against our work but

against its author. This may serve as a

reply to a so-called review which appeared in one of our Western

weeklies.” He concludes with heartfelt

thanks to Dr. Wise for “several evenings spent in revising this volume and for

many courtesies extended to us in general.”

This is followed by a “Brief General Introduction to the Babylonian

Talmud,” where Rodkinson restates his opinion as to what has brought the Talmud

to its present condition:

Rabana Jose, president of the last Saburaic College in

Pumbeditha, who foresaw that his college was destined to be the last, owing to

the growing persecution of the Jews from the days of “Firuz.” He also feared

that the Amoraic manuscripts would be lost in the coming dark days or

materially altered, so he summoned all his contemporary associates and hastily

closed up the Talmud, prohibiting any further additions. This enforced haste caused not only an

improper arrangement and many numerous repetitions and additions, but also led

to the “talmudizing” of articles directly traceable to bitter and relentless

enemies of the Talmud. . . . many theories were surreptitiously added by

its enemies, with the purpose of making it detestable to its adherents. . . .

This closing up of the Talmud did not, however, prevent the importation of

foreign matter into it, and many such have crept in through the agency of the

“Rabanan Saburai” and the Gaonim of every later generation.[21]

Pumbeditha, who foresaw that his college was destined to be the last, owing to

the growing persecution of the Jews from the days of “Firuz.” He also feared

that the Amoraic manuscripts would be lost in the coming dark days or

materially altered, so he summoned all his contemporary associates and hastily

closed up the Talmud, prohibiting any further additions. This enforced haste caused not only an

improper arrangement and many numerous repetitions and additions, but also led

to the “talmudizing” of articles directly traceable to bitter and relentless

enemies of the Talmud. . . . many theories were surreptitiously added by

its enemies, with the purpose of making it detestable to its adherents. . . .

This closing up of the Talmud did not, however, prevent the importation of

foreign matter into it, and many such have crept in through the agency of the

“Rabanan Saburai” and the Gaonim of every later generation.[21]

The third introduction, to tract Sabbath, includes

such remarks as “It has been proven that the seventh day kept holy by the Jews

was also in ancient times the general day of rest among other nations. . . .”[22]

such remarks as “It has been proven that the seventh day kept holy by the Jews

was also in ancient times the general day of rest among other nations. . . .”[22]

The text of the remaining tractates are entirely in

English. Much of the text is, as

Rodkinson had promised, revised, although expurgated might be a more accurate

description; particularly involved discussions or material disapproved of by

Rodkinson being omitted. For example,

in the beginning of Yoma (2a), nineteen of the first thirty-one lines of

gemarah dealing with the parah adumah (red heifer) are omitted.

The first half of the verso (2b) has a discussion of a gezeirah shavah

(a hermeneutic principle based on like terms) concerning the application of the

term tziva (command) to Yom Kippur, also omitted. There are no references to the standard

foliation, established with the editio princeps printed by Daniel

Bomberg (1519/20-23), nor, except for biblical references imbedded in the text,

are the indices accompanying the Talmud, prepared by R. Joshua ben Simon Baruch Boaz for the Giustiniani Talmud (1546-51)

either present or utilized.

There are occasional accompanying brief footnotes. Rodkinson informs the reader in “A Word to

the Public,” at the beginning of Ta’anit, that Rashi’s commentary has,

wherever practical, been “embodied in the text,” denoted by parentheses. Where this was not practical, due to the

vagueness of the phraseology, it has been made an integral part of the

text. When Rash’s commentary is “insufficient

or rather vague” he makes use of another commentary.

English. Much of the text is, as

Rodkinson had promised, revised, although expurgated might be a more accurate

description; particularly involved discussions or material disapproved of by

Rodkinson being omitted. For example,

in the beginning of Yoma (2a), nineteen of the first thirty-one lines of

gemarah dealing with the parah adumah (red heifer) are omitted.

The first half of the verso (2b) has a discussion of a gezeirah shavah

(a hermeneutic principle based on like terms) concerning the application of the

term tziva (command) to Yom Kippur, also omitted. There are no references to the standard

foliation, established with the editio princeps printed by Daniel

Bomberg (1519/20-23), nor, except for biblical references imbedded in the text,

are the indices accompanying the Talmud, prepared by R. Joshua ben Simon Baruch Boaz for the Giustiniani Talmud (1546-51)

either present or utilized.

There are occasional accompanying brief footnotes. Rodkinson informs the reader in “A Word to

the Public,” at the beginning of Ta’anit, that Rashi’s commentary has,

wherever practical, been “embodied in the text,” denoted by parentheses. Where this was not practical, due to the

vagueness of the phraseology, it has been made an integral part of the

text. When Rash’s commentary is “insufficient

or rather vague” he makes use of another commentary.

The New Talmud does not include all of the treatises

in the Babylonian Talmud. All the

tractates in Orders Nashim and Kodashim are omitted, as well as

tractates Berakhot and Niddah, the only treatises in Orders Zera’im

and Tohorot, respectively. The

absence of Berakhot, a popular tractate dealing with prayers and

blessings, is surprising, for sample pages, as noted above, were sent out prior

to the publication of this Talmud. In

fact, Rodkinson had planned to print Berakhot initially, but, as he

relates in the Hebrew introduction, difficulties with the printer prevented him

from completing that tractate. The New

Talmud was completed with a supplementary volume, The History of the Talmud

from the time of its formation. . . . Made up of two volumes in one, it is

much more than a history of the Talmud.

As we shall see, Rodkinson used this book as a vehicle to discuss the

publication of his Talmud, his opponents, and the deleterious consequences of

their opposition.

in the Babylonian Talmud. All the

tractates in Orders Nashim and Kodashim are omitted, as well as

tractates Berakhot and Niddah, the only treatises in Orders Zera’im

and Tohorot, respectively. The

absence of Berakhot, a popular tractate dealing with prayers and

blessings, is surprising, for sample pages, as noted above, were sent out prior

to the publication of this Talmud. In

fact, Rodkinson had planned to print Berakhot initially, but, as he

relates in the Hebrew introduction, difficulties with the printer prevented him

from completing that tractate. The New

Talmud was completed with a supplementary volume, The History of the Talmud

from the time of its formation. . . . Made up of two volumes in one, it is

much more than a history of the Talmud.

As we shall see, Rodkinson used this book as a vehicle to discuss the

publication of his Talmud, his opponents, and the deleterious consequences of

their opposition.

The translation received favorable mention in Reform,

secular and even Christian journals.

These reviews are general in nature, acknowledging the difficulties of

the task undertaken, and the concomitant benefit of opening what was previously

a closed work to a wider public.

secular and even Christian journals.

These reviews are general in nature, acknowledging the difficulties of

the task undertaken, and the concomitant benefit of opening what was previously

a closed work to a wider public.

Excerpts from these reviews are reprinted in The

History. Among them are extracts

from The American Israelite, founded by I. M. Wise, which describes the

translation as a “work which is a credit to American Judaism; a book which

should be in every home . . . a work whose character will rank it with the

first dozen of most important books,” and again, after the appearance of volume

VIII, in 1899, “the English is correct, clear, and idiomatic as any celebrated

English scholar in London or Oxford could make it. We heartily admire also the

energy, the working force of this master mind, the like of which is rare, and

always was. . . .” The Home Library review, printed in its entirety,

concludes, “The reader of Dr. Rodkinson’s own writings easily recognizes in his

mastery of English style, and his high mental and ethical qualifications, ample

assurance of his ability to make his Reconstructed Talmud an adequate text-book

of the learning and the liberal spirit of modern Reformed Judaism. To Christian scholars, teachers, and

students of liberal spirit, his work must be most welcome.”[23]

History. Among them are extracts

from The American Israelite, founded by I. M. Wise, which describes the

translation as a “work which is a credit to American Judaism; a book which

should be in every home . . . a work whose character will rank it with the

first dozen of most important books,” and again, after the appearance of volume

VIII, in 1899, “the English is correct, clear, and idiomatic as any celebrated

English scholar in London or Oxford could make it. We heartily admire also the

energy, the working force of this master mind, the like of which is rare, and

always was. . . .” The Home Library review, printed in its entirety,

concludes, “The reader of Dr. Rodkinson’s own writings easily recognizes in his

mastery of English style, and his high mental and ethical qualifications, ample

assurance of his ability to make his Reconstructed Talmud an adequate text-book

of the learning and the liberal spirit of modern Reformed Judaism. To Christian scholars, teachers, and

students of liberal spirit, his work must be most welcome.”[23]

In the New York Times – Saturday Review of Books

(June 19, 1897) the unnamed reviewer expresses considerable skepticism

concerning the contemporary worth of the Talmud, but concedes it an antiquarian

value comparable to the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Nevertheless, “looking at Mr. Michael L.

Rodkinson’s work as literature, it is a production which has required a vast

amount of knowledge and infinite patience.

The knowledge of the Hebrew has been profound, and the intricacies of

the text are all made clear and plain. . . . An amazing mass of material in

these two volumes will delight the ethnologist, the archaeologist, and the

folklorist, for certainly before the publication of this work, access to the

Talmud has been well-nigh impossible to those who were not of Semitic origin.” The reviewer finds the strongest endorsement

of the work in the testimony of the Rev. Isaac Wise.

(June 19, 1897) the unnamed reviewer expresses considerable skepticism

concerning the contemporary worth of the Talmud, but concedes it an antiquarian

value comparable to the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Nevertheless, “looking at Mr. Michael L.

Rodkinson’s work as literature, it is a production which has required a vast

amount of knowledge and infinite patience.

The knowledge of the Hebrew has been profound, and the intricacies of

the text are all made clear and plain. . . . An amazing mass of material in

these two volumes will delight the ethnologist, the archaeologist, and the

folklorist, for certainly before the publication of this work, access to the

Talmud has been well-nigh impossible to those who were not of Semitic origin.” The reviewer finds the strongest endorsement

of the work in the testimony of the Rev. Isaac Wise.

Additional reviews, also positive, were published with

the completion of volume VIII on Seder Moed in 1899. The New York Times reviewer now writes (November 25, 1899)

that “The importance of Mr. Rodkinson’s work need not be questioned. The Talmud as he has translated it will take

its place in all theological and well appointed libraries indifferent as to

creed.” A third review (July 7, 1900),

at the time of the appearance of the volume IX, begins “Mr. Rodkinson must be

admired for the courage, perseverance and untiring industry with which he has

undertaken and continues to present the English speaking public the successive

volumes of the Talmud.” The review

concludes, however, with a cautionary note suggesting Rodkinson “procure for

the coming volumes a more careful revision of the translation, because,

according to the ‘pains (or care) so much more the reward of appreciation.’”

the completion of volume VIII on Seder Moed in 1899. The New York Times reviewer now writes (November 25, 1899)

that “The importance of Mr. Rodkinson’s work need not be questioned. The Talmud as he has translated it will take

its place in all theological and well appointed libraries indifferent as to

creed.” A third review (July 7, 1900),

at the time of the appearance of the volume IX, begins “Mr. Rodkinson must be

admired for the courage, perseverance and untiring industry with which he has

undertaken and continues to present the English speaking public the successive

volumes of the Talmud.” The review

concludes, however, with a cautionary note suggesting Rodkinson “procure for

the coming volumes a more careful revision of the translation, because,

according to the ‘pains (or care) so much more the reward of appreciation.’”

The American Israelite (August 17, 1899) enthusiastically endorses the work

by “the great Talmudist, Rodkinson” taking “special pride” in his “gigantic

work” and urging support for “this great enterprise.” To the question as to how Rodkinson came to this “exceptional

clearness” it responds “Mr Rodkinson never frequented any Yeshibah in

Poland or elsewhere; so he never learned that Pilpulistic, scholastic

wrangling and spouting . . . he is entirely free from this corruption, and this

is an important recommendation for his English translation.” The Independent reviewed the

translation at least five times. The

second review (April 7, 1898) notes the opposition to Rodkinson’s translation, and

concludes, “If it is not satisfactory let a syndicate of rabbis do better.” The Evangelist (November 18, 1897),

echoing Rodkinson, remarks that the Talmud was previously “almost inaccessible

to even Hebrew students” due to the fact that its text is “to the last degree

corrupt, marginal notes and glosses having crept in to an unprecedented degree,

owing to the fact that it was kept in manuscript for generations after the

invention of printing.” Previous

attempts to edit the text were hopeless, a complete revision of the text being

required. “Rabbi Rodkinson has at last

effected this textual revision . . . a very valuable contribution to

scholarship.”

by “the great Talmudist, Rodkinson” taking “special pride” in his “gigantic

work” and urging support for “this great enterprise.” To the question as to how Rodkinson came to this “exceptional

clearness” it responds “Mr Rodkinson never frequented any Yeshibah in

Poland or elsewhere; so he never learned that Pilpulistic, scholastic

wrangling and spouting . . . he is entirely free from this corruption, and this

is an important recommendation for his English translation.” The Independent reviewed the

translation at least five times. The

second review (April 7, 1898) notes the opposition to Rodkinson’s translation, and

concludes, “If it is not satisfactory let a syndicate of rabbis do better.” The Evangelist (November 18, 1897),

echoing Rodkinson, remarks that the Talmud was previously “almost inaccessible

to even Hebrew students” due to the fact that its text is “to the last degree

corrupt, marginal notes and glosses having crept in to an unprecedented degree,

owing to the fact that it was kept in manuscript for generations after the

invention of printing.” Previous

attempts to edit the text were hopeless, a complete revision of the text being

required. “Rabbi Rodkinson has at last

effected this textual revision . . . a very valuable contribution to

scholarship.”

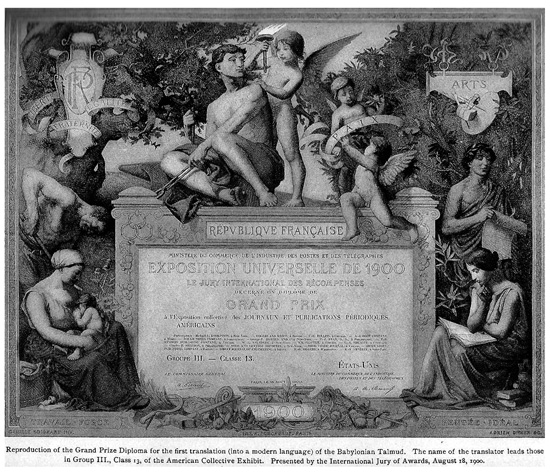

Several of the later volumes include a reproduction of

the Grand Prize Diploma from the Republique Francaise, Ministere du Commerce

de l’Industrie des Postes et des Telegraphes Exposition Universelle de 1900

for, according to the accompanying description, “the first translation (into a

modern language) of the Babylonian Talmud.

The name of the translator leads those in Group III, Class 13, of the

American Collection Exhibit. Presented

by the International Jury of Awards, August 18, 1900.” Here it is.

the Grand Prize Diploma from the Republique Francaise, Ministere du Commerce

de l’Industrie des Postes et des Telegraphes Exposition Universelle de 1900

for, according to the accompanying description, “the first translation (into a

modern language) of the Babylonian Talmud.

The name of the translator leads those in Group III, Class 13, of the

American Collection Exhibit. Presented

by the International Jury of Awards, August 18, 1900.” Here it is.

Praise in Reform, Christian and secular journals,

awards and faint praise from foreign dignitaries notwithstanding, there was

significant criticism of the New Edition of the Babylonian Talmud. Skepticism at an English translation of the

Talmud was expressed by no less astute an observer of the Jewish scene than

Abraham Cahan:

awards and faint praise from foreign dignitaries notwithstanding, there was

significant criticism of the New Edition of the Babylonian Talmud. Skepticism at an English translation of the

Talmud was expressed by no less astute an observer of the Jewish scene than

Abraham Cahan:

I hear they are translating the Talmud into modern

languages. It cannot be done. They may render the old Chaldaic or Hebrew

into English, but the spirit which hovers between the lines, which goes out of

the folios spreading over the whole synagogue, and from the synagogues over the

out-of-the-way town, over the dining table of every hovel, over the soul of

every man, woman, or child; that musty, thrilling something which should be

called Talmudism can no more be translated into English or German or French

than the world of Julius Caesar can be shipped . . . to the Brooklyn Bridge.[24]

languages. It cannot be done. They may render the old Chaldaic or Hebrew

into English, but the spirit which hovers between the lines, which goes out of

the folios spreading over the whole synagogue, and from the synagogues over the

out-of-the-way town, over the dining table of every hovel, over the soul of

every man, woman, or child; that musty, thrilling something which should be

called Talmudism can no more be translated into English or German or French

than the world of Julius Caesar can be shipped . . . to the Brooklyn Bridge.[24]

Less nostalgic, more critical, and certainly more

analytical than the positive reviews, were the negative responses to the “New

Edition of the Babylonian Talmud.”

These reviews were written by individuals with Talmudic training, as

well as scholarly credentials, for whom the Talmud was not a closed book. They were, therefore, capable of properly

evaluating Rodkinson’s achievement.

Among the numerous negative articles are three by individuals whose

endorsements for the projected translation had been printed in the prospectus:

B. Felsenthal, M. Jastrow, and Kaufmann Kohler. All took special exception to

Rodkinson’s claim of having restored the original Talmud, apart from their

criticism of the translation. Indeed, there