The Ghetto Library and Daily Life Under the Nazis

The Ghetto Library and Daily Life Under the Nazis

In giving the public this opportunity to learn more about the spiritual resistance of the Vilna Ghetto, we seek to immortalize the moral heroism of the victims of the Holocaust. And bring to light the phenomenon of the vitality and endurance of the Jewish people – throughout their long existence, laden with suffering and restrictions, it has forced them not to give up but to seek the means of self-expression and foster their traditions and culture no matter what adversity they faced.

Jevgenija Biber, “To the Reader,” Vilna Ghetto Posters

During the Holocaust, resistance took on many forms. In some instances, it was armed resistance, such as in the Warsaw ghetto and the Vilna ghetto uprisings. Other types were religious or spiritual, such as Jews performing mitzvahs or studying Torah in the most horrific situations and, for example, refusing to eat on Yom Kippur in concentration camps where their food rations were already placing them at risk of starvation. However, there is another type, and that was refusing to allow the Nazis to control everyday life. After the Soviets re-entered Vilna in 1944, among the few survivors, some began collecting whatever documents and other materials that they could regarding Jewish life before the war. Eventually, this would form the core collection of a short-lived Jewish Museum. The museum operated until 1948 when the Soviet-controlled government confiscated all the materials and dumped them into a repurposed church. It would be decades before they were placed in more appropriate locations. A portion of those documents went to the Lithuanian Central State Archives.

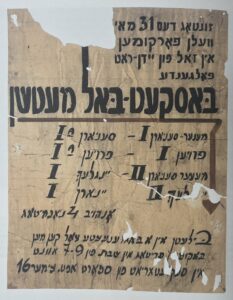

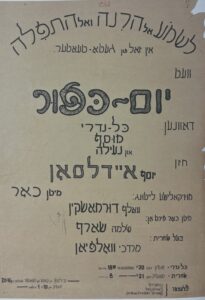

Among those in the Archive are posters and broadsides from the Vilna Ghetto period. These are evidence of continuing daily life even after there had been massive deportations and murders of Jews. Nonetheless, when the opportunity presented itself, whether for intellectual events, concerts, or even sports, the Jews ferociously fought to continue to live their lives. 2005, the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in Vilnius published some of these Vilna Ghetto Posters, compiled by Jevgenija Biber, Rocha Kostanian, and Judita Rozina. (Unfortunately, as far as we know, the book is only available at the Museum’s bookstore in Vilnius.)

For example, one poster announces a basketball tournament that includes men, women, and seniors. Another announces the opening of the Jewish ghetto theater, whereas others announce specific plays and other cultural events, such as a night commemorating Haim Nahum Bialik. The theater hall also housed Yom Kippur services in 1942.

On the intellectual side, there were lectures on Jewish history, one on the zugos, and the pairs of Rabbis in the Mishna. Another was an announcement of sermons delivered on the Yom Tefillah that was declared in February 1942.

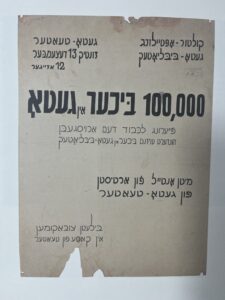

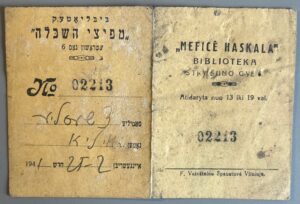

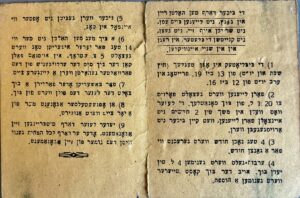

One of the most astounding documents was an announcement that on Sunday, December 13, 1942, at noon, a “Celebration of one hundred thousand books loaned by the Ghetto library” since it opened in September 1941. The ghetto library was in the former Mefitsei Haskalah Library. That library was among the three largest in Vilna. The other two, the Strashun Library and the YIVO Library were closed by the Nazis. This was nearly the same circulation numbers, 90,000 yearly, as before the Nazi invasion and ghettoization of the Vilna’s Jews. Most recently, in the portion of the pre-war documents now at the Judaica Centre at the Lithuanian National Library, a reader’s library card was discovered that slightly pre-dates the formation of the ghetto library. This card, from February 21, 1941, provides the library’s rules, including an admonishment not to leave the books in rain or snow, how to calculate due dates, and fines for overdue books.

In addition to the poster is a highly detailed description of the library and its operations that survived the Holocaust. In October 1942, Kruk published “The Library and Reading Room in the Vilna Ghetto, Strashun Street.” The document was originally in Yiddish (and the original is at the YIVO Institute in New York, available here), but Zachary Baker translated it into English and added notes. (See Herman Kruk, “Library and Reading Room in the Vilna Ghetto, Strashun Street 6,” translated by Zachary Baker, in The Holocaust and the Book, Destruction and Preservation, ed. Jonathan Rose, University of Massachusetts Press, 2001, 171-200).

Kruk provides a prehistory and then specifically recounts the library’s activities since it reopened in September 1941. Among other details, before the war, there were 2,000 subscribers, and in 1940-41, with the influx of Jews from all over Eastern Europe, that number doubled. By September 1941, there were 4,700 subscribers. Men and women were represented almost equally, although women had a slight advantage. The fact that the library reached 100,000 books by December is especially remarkable, in that it was closed for several months as it was too cold to operate.

Kruk notes significant changes in subject matter and books during this period. For example, there was a 600% increase in readership for War and Peace, and books on war, such as All is Quiet on the Western Front and Emile Zola’s War, were also in high demand. The library’s readers of history were focused on books regarding the Crusades and other martyrdom literature. However, there have been significant changes to the library since before the war. Most notably, 15-30-year-olds made up the bulk of readers during the pre-war period, while in 1942, that number had dropped precipitously. Kruk explains that age groups bearing the brunt of forced labor were too tired to contemplate reading at the end of an exhausting day.

Kruk summarizes the popularity of libraries and readings, even in the face of death: “A human being can endure hunger, poverty, pain, and suffering, but he cannot tolerate isolation. Then, more than in normal times, the attraction of books and reading is almost indescribable.”

One thought on “The Ghetto Library and Daily Life Under the Nazis”

Wonderful post on Yom Hashoah.