A nay bintl briv: Personal Reminiscences of Rabbi Israel Meir ha-Kohen from the Yiddish Republic of Letters

A nay bintl briv:

Personal Reminiscences of Rabbi Israel Meir ha-Kohen from the Yiddish Republic of Letters

Shaul Seidler-Feller

Editor’s note: The present post is part one of a two-part essay. Part two can be found here.

Introduction

Beginning on January 20, 1906, Abraham (Abe) Cahan (1860–1951), the legendary founder and longtime editor of the Yiddish-language Forverts newspaper in New York, published a regular agony uncle column famously entitled A bintl briv (A Bundle of Letters; often Romanized A Bintel Brief).[1] Herein he reproduced missives sent to the daily by its largely Eastern European immigrant readership seeking advice on a range of personal issues, followed by his wise, insightful counsel.[2] While today this once-immensely-popular feature may have quietly evanesced into the mists of Yiddish journalistic history,[3] it is my intention here to revive it, if only briefly and in altered form, via transcription, translation, and discussion of two letters penned to the distinguished Forverts columnist Rabbi Aaron B. Shurin.

Shurin, born in Riteve (present-day Rietavas, Lithuania) on the second day of Rosh Hashanah 5673 (September 13, 1912)[4] to his parents Rabbi Moses and Ruth, learned in his youth at the heder and yeshivah of Riteve (the latter founded by his father) and spent the years 1928–1936 at the yeshivot of Ponevezh (present-day Panevėžys, Lithuania) and Telz (present-day Telšiai, Lithuania).[5] In 1936, he joined the rest of his family in the Holy Land, to which it had immigrated the previous year, and soon thereafter he continued his studies at the yeshivot of Hebron (as transplanted to Jerusalem) and Petah Tikva, as well as at the 1938 Summer Seminar in Tel Aviv under Prof. Yehuda Even Shmuel (Kaufman; 1886–1976).[6] The following year (1939), he received yoreh yoreh and yadin yadin semikhot from Rabbis Meir Stolewitz (1870–1949), Isser Zalman Meltzer (1870–1953), Reuven Katz (1880–1963), and Isaac ha-Levi Herzog (1888–1959) and in 1940 moved again, this time to New York, to which his father had relocated circa 1937.[7] At that point, he began studying at Yeshiva College and Columbia University, and in 1941–1942 he simultaneously taught Bible and Hebrew language and literature in YC; he would later go on to occupy a position on the Judaic studies faculty at Stern College for Women for many years (1949–1956 and 1966–2001).[8]

In the years that followed, in addition to teaching at YU, Shurin served as cofounder and vice president of Poalei Agudath Israel (1941–1947), rabbi of two synagogues (Beth Hacknesseth Anshei Slutsk at 34 Pike Street in Manhattan [1941–1945] and Toras Moshe Jewish Center at 4314 Tenth Avenue in Brooklyn [1945–1947]), and principal of a day school (Talmud Torah Hechodosh at 146 Stockton Street in Brooklyn [1949–1953]), among several other leadership positions.[9] However, it is his sixty-two-plus-year career at the Forverts on which I wish to focus here. Already in his youth, as a talmid in Telz and then in Israel, he began writing articles and studies for various Hebrew and Yiddish publications, and when he came to America (to quote him directly), “Anywhere I could write, I did […] I enjoyed it, and I compiled a portfolio of articles on a wide range of subjects. One day, a friend said to me, ‘You should write for the Forward.’ I laughed.”[10] At the time, the Forverts was by far the most widely read Jewish newspaper, with a daily circulation of over 100,000 copies, and was avowedly secular in orientation, even publishing on Shabbat and yom tov (although it was respectful of the religious).[11] Nevertheless, despite these challenges to a young, aspiring Orthodox journalist, Shurin took the idea of working at the Forverts to the famed historian and bibliophile Chaim Lieberman (1892–1991) who, after reading a sample of his work, recommended him to Harry Lang (1888–1970), a managing editor at the paper, and shortly thereafter editor Hillel (Harry) Rogoff (1882–1971) hired him.[12] From 1944 to 1983, Shurin wrote approximately two columns per week; when the Forverts became a weekly in the latter year, he, too, switched to one column per week until his retirement in 2007.[13]

For the most part, Shurin’s Forverts articles focused on religious topics, Jewish education, social-political issues in Israel (particularly those concerning the Orthodox parties), and the lives of great Jewish historical figures.[14] The aforementioned letters written to Shurin were sent in response to two of these columns, separated by eight years. His son David was kind enough to transfer them to Seforim Blog editor Eliezer Brodt (who then e-mailed scans to me) and to give full permission for their publication and translation below.[15]

First Letter

In honor of the sesquicentennial of what some consider the birth year of Rabbi Israel Meir ha-Kohen, the world-renowned Hafets Hayyim,[16] Shurin published an article in the Forverts treating the most important aspects of this great leader’s biography, focusing on his legendarily superlative piety, as well as his literary, educational, and political activities on behalf of European Jewry.[17] Not long thereafter, he received the following letter:

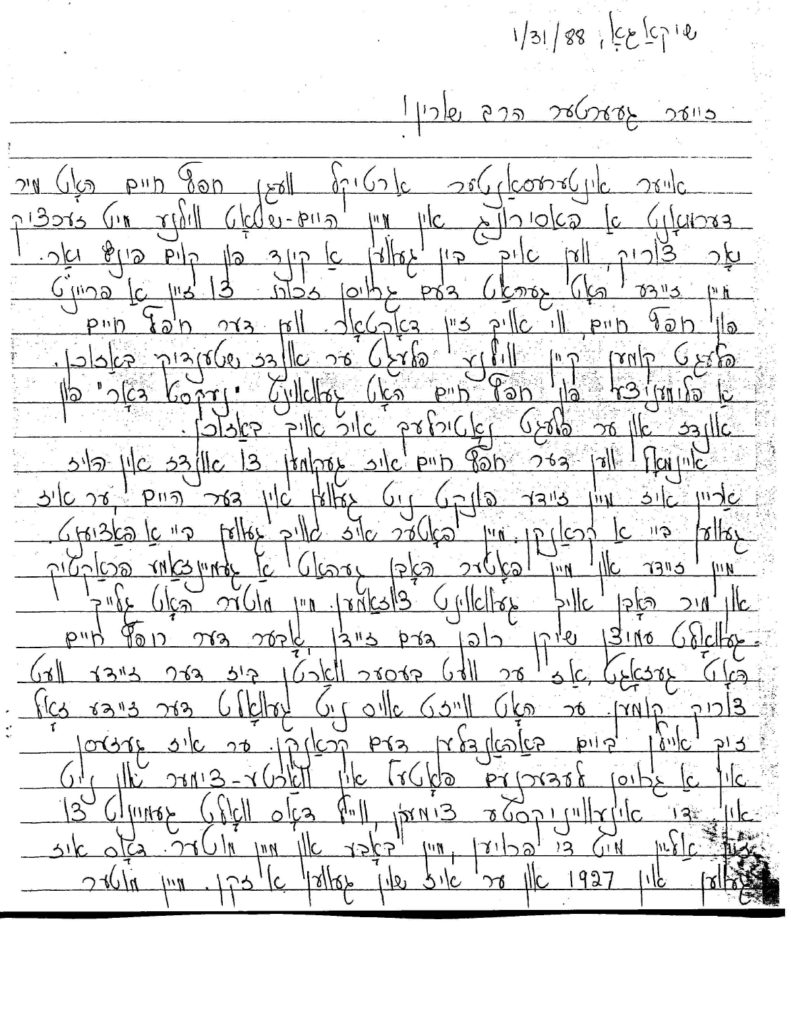

שיקאַגאָ, 1/31/88

!זייער געערטער הרב שורין

אייער אינטערעסאַנטער אַרטיקל וועגן חפץ חיים האָט מיר

דערמאָנט אַ פּאַסירונג אין מיין היים-שטאָט ווילנע מיט זעכציק

.יאָר צוריק, ווען איך בּין געווען אַ קינד פון קוים פינף יאָר

מיין זיידע האָט געהאַט דעם גרויסן זכות צו זיין אַ פריינט

פון חפץ חיים, ווי אויך זיין דאָקטאָר. ווען דער חפץ חיים

.פלעגט קומען קיין ווילנע פלעגט ער אונדז שטענדיק בּאַזוכן

אַ פּלימעניצע פון חפץ חיים האָט געוואוינט ״נעקסט דאָר״ פון

.אונדז און ער פלעגט נאַטירלעך איר אויך בּאַזוכן

איינמאָל ווען דער חפץ חיים איז געקומען צו אונדז אין הויז

אַריין איז מיין זיידע פּונקט ניט געווען אין דער היים, ער איז

.געווען בּיי אַ קראַנקן. מיין פאָטער איז אויך געווען בּיי אַ פּאַציענט

מיין זיידע און מיין פאָטער האָבּן געהאַט אַ געמיינזאַמע פּראַקטיק

און מיר האָבּן אויך געוואוינט צוזאַמען. מיין מוטער האָט גלייך

געוואָלט עמיצן שיקן רופן דעם זיידן, אָבער דער חפץ חיים

האָט געזאָגט, אַז ער וועט בּעסער וואַרטן בּיז דער זיידע וועט

צוריק קומען. ער האָט ווייזט אויס ניט געוואָלט דער זיידע זאָל

זיך איילן בּיים בּאַהאַנדלען דעם קראַנקן. ער איז געזעסן

אין אַ גרויסן לעדערנעם פאָטעל אין וואַרטע-צימער און ניט

אין די אינעווייניקסטע צימערן, ווייל דאָס וואָלט געמיינט צו

זיין אַליין מיט די פרויען, מיין בּאָבּע און מיין מוטער. דאָס איז

געווען אין 1927 און ער איז שוין געווען א זקן. מיין מוטער

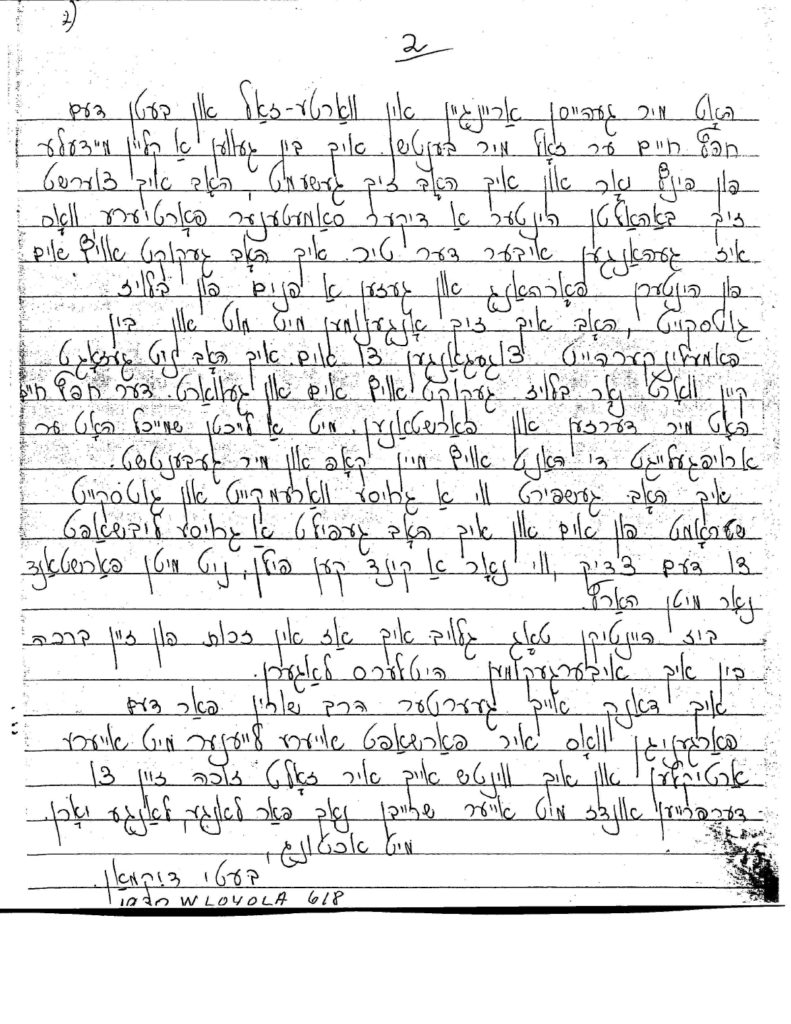

2

האָט מיר געהייסן אַריינגיין אין וואַרטע-זאַל און בּעטן דעם

חפץ חיים ער זאָל מיר בּענטשן. איך בּין געווען אַ קליין מיידעלע

פון פינף יאָר און איך האָבּ זיך געשעמט, האָבּ איך צוערשט

זיך בּאַהאַלטן הינטער אַ דיקער סאַמעטענער פּאָרטיערע וואָס

איז געהאַנגען איבּער דער טיר. איך האָבּ געקוקט אויף אים

פון הינטערן פאָרהאַנג און געזען אַ פנים פון בּלויז

גוטסקייט, האָבּ איך זיך אָנגענומען מיט מוט און בּין

פּאמעלינקערהייט צוגעגאַנגען צו אים. איך האָבּ ניט געזאָגט

קיין וואָרט נאָר בּלויז געקוקט אויף אים און געוואַרט. דער חפץ חיים

האָט מיר דערזען און פאַרשטאַנען. מיט אַ לייכטן שמייכל האָט ער

.אַרויפגעלייגט די האַנט אויף מיין קאָפּ און מיר געבּענטשט

איך האָבּ געשפּירט ווי אַ גרויסע וואַרעמקייט און גוטסקייט

שטראָמט פון אים און איך האָבּ געפילט אַ גרויסע ליבּשאַפט

צו דעם צדיק, ווי נאָר אַ קינד קען פילן, ניט מיטן פאַרשטאַנד

.נאָר מיטן האַרץ

בּיז היינטיקן טאָג גלויבּ איך אַז אין זכות פון זיין ברכה

.בּין איך איבּערגעקומען היטלערס לאַגערן

איך דאַנק אייך געערטער הרב שורין פאַר דעם

פאַרגעניגן וואָס איר פאַרשאַפט אייערע לייענער מיט אייערע

אַרטיקלען און איך ווינטש אייך איר זאָלט זוכה זיין צו

.דערפרייען אונדז מיט אייער שרייבּן נאָך פאַר לאנגע, לאַנגע יאָרן

,מיט אכטונג

.בּעטי דיִקמאַן

1930 W LOYOLA 618

Chicago, 1/31/88

To the highly esteemed Rabbi Shurin!

Your interesting article about the Hafets Hayyim reminded me of a story that took place in my hometown of Vilna sixty years ago, when I was a child barely five years of age. My grandfather was very fortunate to be a friend of the Hafets Hayyim, as well as his physician. When the Hafets Hayyim would come to Vilna, he would always visit us. A niece of his lived next door, and he would also, naturally, go to see her.

One time when the Hafets Hayyim came to our house, my grandfather, as luck would have it, was not home; he was tending to someone ill. My father, too, was with a patient. My grandfather and father had a shared practice, and we also all lived together. My mother immediately suggested sending someone to call for my grandfather, but the Hafets Hayyim said that he preferred to wait until my grandfather returned. He evidently did not want my grandfather to rush his treatment of the sick person. He sat down in a large leather armchair in the foyer,[18] not in the innermost rooms, because that would have meant being secluded with the women – my grandmother and mother. This was in 1927, when he was already an elderly man. My mother

2

told me to go to the hallway[19] and ask the Hafets Hayyim to bless me. I was a small, shy girl of five years, so I initially hid behind a thick velvet portiere hanging over the door. But when I peered at him from behind the curtain and saw a face of pure goodness, I mustered up my courage and slowly approached him. I did not say a word; I just looked at him and waited. The Hafets Hayyim caught sight of me and understood. With an easy smile, he lay his hand on my head and blessed me. I sensed a great warmth and goodness streaming forth from him and felt much love for this righteous man, as only a child can – not with the mind but with the heart.

To this day, I believe that it is on account of his blessing that I survived Hitler’s camps.

I thank you, esteemed R. Shurin, for the joy that you bring to your readers with your columns and wish you the good fortune to continue delighting us with your writing for many, many years to come.

Respectfully,

Betty Dickman

1930 W Loyola 618

On April 14, 1997, Donna Puccini interviewed Betty Dickman about her experiences during the Holocaust on behalf of what is today the USC Shoah Foundation’s Institute for Visual History and Education.[20] From that conversation we learn that Dickman was born Isabella Margolin on April 9, 1922 in Vilna – then part of Poland and called Wilno but today known as Vilnius, Lithuania – as the only child of her parents, Mones (1893–1941) and Henya (1894–1943) Margolin. As already noted in the letter, her maternal grandparents, Chaim and Rose Bruk, lived together with them, and both her grandfather and father were physicians, while her grandmother and mother stayed home with their Polish maid.[21] Chaim Bruk was a prominent member of the Vilna Jewish community who sat on the board of directors of the Tiferes Bachurim Society (at 6 Niemiecka [present-day Vokiečių] Street),[22] helped to found the city’s Miszmeres Chojlim charitable hospital (at 5 Kijowska [present-day Kauno] Street),[23] and served as gabbai of Zalkin’s (formerly Zemel’s) kloyz (at 2 Rudnicka [present-day Rūdninkų] Street),[24] which was located right next door to the family’s apartment building at 4 Rudnicka Street.[25] According to Dickman, when he passed away in 1936 at the age of 70, all the stores lining the streets through which the funeral procession passed were closed, and “there must have been about twenty-five thousand [!] people at that funeral.”

Aside from its value as a firsthand account of the profoundly human, down-to-earth, and kindhearted character of the Hafets Hayyim, this letter also touches on, and complicates our understanding of, at least three aspects of his biography and religious worldview.[26] First and foremost is his attitude toward medicine. The Hafets Hayyim was famous for his pure, unshakable faith in God,[27] relying on Him to heal the sick even when traditional medical interventions had not been attempted.[28] However, a number of incidents recorded by the Hafets Hayyim’s biographers point to a willingness to, and even insistence on the importance of, consult(ation) with physicians about health-related issues.[29] While I have so far not succeeded in corroborating the letter’s claim that Bruk served as the Hafets Hayyim’s personal doctor,[30] it is evident that both certain members of the Hafets Hayyim’s family and he himself had recourse to medical professionals at various stages of their lives[31] – a point that comes through clearly in Dickman’s writing.

Another interesting aspect of this story concerns the Hafets Hayyim’s willingness to bless the young girl. Though many petitioned him to pray on their behalf or offer them a blessing,[32] the Hafets Hayyim often refused on principle to do so, noting that God makes Himself equally available to every Jew, no matter his status in the community, and that He would actually prefer to hear directly from His children than from an intermediary.[33] The fact that he made an exception in this case, while certainly not unheard-of,[34] is nevertheless noteworthy, and it deepens our appreciation of his paternal conduct with this shy little girl.

Finally, attention should be directed toward the Hafets Hayyim’s halakhic stance on yihud. While most posekim assume that secluding oneself with a married woman whose husband is in town (ba‘alah ba-ir) is permissible even ab initio,[35] the letter reports that the Hafets Hayyim would not allow himself to sit together with Mrs. Bruk and Mrs. Margolin even though their husbands were not far away.[36] Interestingly, this humra, which is based on Rashi’s understanding of a passage in the Talmud,[37] seemingly contradicts the Hafets Hayyim’s own ruling on the matter in his Sefer nidhei yisra’el, intended for Jews who had immigrated to America.[38] It would thus appear that we have here an instance in which the Hafets Hayyim’s personal practice reflected a higher degree of stringency regarding halakhah than he required of others.[39]

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

* I wish at the outset to express my gratitude to Eliezer Brodt for furnishing me with the opportunity to compose this essay and for his patience during its long gestation. Additional thanks go to his fellow editors at the Seforim Blog, particularly the incomparable Menachem Butler, whose bibliographical reach seems unlimited. Finally, I am indebted to my friends Eliyahu Krakowski, Daniel Tabak, and Shlomo Zuckier for their corrections and comments to an earlier draft of this piece that, taken together, improved it considerably.

[1] On the inception of A bintl briv, see Abraham Cahan, Bleter fun mayn leben, vol. 4 (New York: Forward Association, 1928), 471-478. See also “Treasures From the Forverts’ Archive – Chapter #3. A Bintel Brief (1)” (watch at about 1:13) (accessed August 19, 2019). For the historical background behind, and contemporary influences upon, this feature, see Steven Cassedy, “A Bintel brief: The Russian Émigré Intellectual Meets the American Mass Media,” East European Jewish Affairs 34,1 (2004): 104-120.

[2] After two to three years, Cahan tells us, his many other responsibilities at the paper did not allow him to continue answering the letters personally, so that he had to ask other members of his staff to compose the responses (Bleter, 483).

[3] The most recent column, published in a dedicated corner of The Jewish Daily Forward website called The Bintel Brief, is dated May 24, 2010 (accessed August 19, 2019). Anthologies of selected letters in English translation have appeared as Isaac Metzker (ed.), A Bintel Brief: Sixty Years of Letters from the Lower East Side to the Jewish Daily Forward, trans. Diana Shalet Levy with Bella S. Metzker (New York: Ballantine Books, 1971), and Isaac Metzker (ed.), A Bintel Brief: Letters to the Jewish Daily Forward[,] 1950–1980, trans. Bella S. Metzker and Diana Shalet Levy (New York: The Viking Press, 1981). More recently, some of these missives have been adapted into graphic novel form by Liana Finck as A Bintel Brief: Love and Longing in Old New York (New York: Ecco, 2014).

[4] Anon., “About the Author,” in Aaron B. Shurin, Moadim Lesimcha: Insights[,] Explanations and Stories on the Jewish Holidays (Brooklyn: Aaron B. Shurin, 2006), xi-xx, at p. xi. Some sources date his birth to 1913 or even 1914, but these are clearly mistaken given that when he died on 24 Sivan 5772 (June 14, 2012), he was just a few months shy of his one-hundredth birthday. See, e.g., David Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah la-halutsei ha-yishuv u-bonav: demuyyot u-temunot, vol. 10 (Tel Aviv: Sifriyyat Rishonim, 1959), 3474-3475, at p. 3474, translated/adapted somewhat inaccurately and laconically in Alter Levite, Dina Porat, and Roni Stauber (eds.), A Yizkor Book to Riteve: A Jewish Shtetl in Lithuania (Cape Town: The Kaplan-Kushlick Foundation, 2000), 105-106, at p. 105; Elias Schulman, Leksikon fun forverts shrayber zint 1897, ed. Simon Weber (New York: Forward Association, 1987), 90-91, at p. 90; Berl Kagan, Yidishe shtet, shtetlekh un dorfishe yishuvim in lite biz 1918: historish-biografishe skitses (New York: Berl Kagan, 1991), 556-557, at p. 556; and Alex Mindlin, “A Religious Voice in a Secular Forest,” The New York Times (November 28, 2004). I thank Chana Pollack, Archivist at The Jewish Daily Forward, for sending me a copy of the Leksikon for my personal use.

As an aside, and since I know that the Seforim Blog has a special interest in issues surrounding plagiarism, one can find (mild) examples of this phenomenon in the announcement of Shurin’s passing published by Casriel Bauman, “A Legend in His Time: Rabbi Aharon Ben Zion Shurin z”l,” Matzav.com (June 14, 2012) (accessed August 19, 2019) – subsequently reprinted with minor modifications in the Queens Jewish Link 1,12 (June 28, 2012): 89 – which fails to cite both Tidhar’s encyclopedia entry and the New York Times interview as its sources.

[5] Anon., “About the Author,” xi; see also Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474. For photographs of Shurin (at that point still going by the original family name, Mishuris) and his friends taken in Telz on 3 Adar II 5695 (March 8, 1935), see the following Ebay listings: 1, 2 (accessed August 19, 2019). For a recent photograph of the dilapidated yeshivah building in Telz, taken by Richard Schofield as part of his photo essay Back to Shul (Vilnius: International Centre for Litvak Photography, 2018), see here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[6] Anon., “About the Author,” xi-xii; see also Anon., “Totse’ot ha-behinot be-seminar ha-kayits mi-ta‘am ha-v[a‘ad] ha-l[e’ummi],” Ha-tsofeh 3,318 (January 13, 1939): 1. (Cf. the 1940 United States Census record for Manhattan [accessed June 21, 2019], according to which Aaron, like the rest of his family, was living in “Tel-a-Viv” as of April 1, 1935. This seems unlikely given the date inscribed on the photographs mentioned in the previous note.) According to Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474, Shurin also attended a gymnasium at night while learning at the Lomzher yeshivah in Petah Tikva.

[7] Anon., “About the Author,” xii; see also Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474-3475, and the announcement of his move to America in Ha-mashkif 2,244 (January 25, 1940): 4. His younger brother, Rabbi Israel Shurin (1918–2007), followed a very similar educational path. See the biographical sketch published originally in Yated Neeman with contributions from Rabbi Mordechai Kamenetzky and Sharon Katz, entitled “Rav Yisroel Shurin, z”l: A Revered Rav and a Link to a Lithuanian Past” (accessed August 19, 2019).

[8] Anon., “About the Author,” xii. See also Anon., Columbia University in the City of New York: Supplement to the Directory Number, 1945 (New York: New York, 1945), 45; Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474; the 1967 volume of Stern’s yearbook, Kochaviah, 35 (where he is referred to as “Arthur,” rather than “Aaron,” Shurin); and YU Review: The Magazine of Yeshiva University (Fall 2005): 30. (For the record, the latest Kochaviah yearbook in which I was able to locate Shurin on the faculty pages was the 1997 volume [p. 21]; he did not appear there in the 1998 and 2000 editions, and neither the YU Archives nor Stern’s Hedi Steinberg Library held copies of the 1999 and 2001 volumes at the time I visited them [if indeed those editions were ever actually published]. I thank Shulamith Z. Berger, Curator of Special Collections and Hebraica-Judaica, for allowing me to examine the Archives’ holdings.) As noted by Tidhar and others, Shurin edited the Hebrew section of Eidenu (New York: Students of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, 1942), a volume dedicated to the memory of YU President Rabbi Dr. Bernard Revel (1885–1940).

[9] Anon., “About the Author,” xii; see also Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474. For some of his other organizational affiliations, see Anon., “About the Author,” xviii. See also lots 169, 170, 191, 198, 200, 205, 210, and 211 from a Kestenbaum & Company auction held on April 7, 2016, which included letters written to Shurin and his father-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Dov-Ber Rivkin (1892–1976), by some of the leading lights of the Jewish world at the time (accessed August 19, 2019). It is interesting to note that Rabbis Eliezer Silver (1882–1968) and Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903–1993) both apparently read Shurin’s columns in the Forverts.

[10] Quoted in Yisroel Besser, “Defending the Past in the Pages of the Forward: Rabbi Aaron Benzion Shurin’s Six Decades of Journalism,” Mishpacha (May 26, 2010): 26-33, at p. 29. For more on Shurin’s writing outside of the context of his work for the Forverts, including his many rabbinic publications, see Anon., “About the Author,” xiv-xvii, and Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3474-3475.

Relatedly, Israel Mizrahi notes that Shurin’s personal library of approximately two thousand volumes “included many classics as well as obscure works from the last century as well as a very strong showing of newspapers, from the 19th century through the WWII period, with many bound volumes of rare newspapers present.” See “Recent Acquisitions at Mizrahi Bookstore, the libraries of Aaron Ben-Zion Shurin […],” Musings of a Jewish Bookseller (March 29, 2016) (accessed August 19, 2019). One of his books, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s Ad eimatai dibberu ivrit? (New York: Kadimah, 1919), comprised lot 3 of Winner’s Auctions’ July 19, 2016 sale (accessed August 19, 2019).

[11] Gennady Estraikh and Zalman Newfield, “Grandfathers against Bar Mitzvahs: Secular Immigrant Jews Confront Religion in 1940s America,” Zutot 9 (2012): 73-84, at p. 74; see also Gennady Estraikh, “A Mid-Twentieth-Century Quest for Jewish Authenticity: The Yiddish Daily Forverts’ Warming to Religion,” in Eliyana R. Adler and Sheila E. Jelen (eds.), Reconstructing the Old Country: American Jewry in the Post-Holocaust Decades (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2017), 111-134, at pp. 111-112. On the occasion of the Forverts’ eightieth anniversary, Shurin himself would reflect that “the Forverts has […] been very friendly to the yeshivah world throughout the years that I have been a collaborator on the Forverts editorial staff.” See Aaron B. Shurin, “Idish lebn in amerike,” Forverts (April 24, 1977): B8, B24, at p. B24.

In his interview with The New York Times, Shurin asserts that the Forverts had a quarter million readers at the time he was hired, but Estraikh and Newfield write that that number was accurate for the 1920s, not the 1940s.

[12] Besser, “Defending,” 30, explains the decision to bring an Orthodox rabbi onboard by noting that “times were changing and the Forward management perceived that they had to provide their Orthodox readership – which was immense – with a column geared to their needs, coverage and perspective of the issues that concerned them.” Similarly, Mindlin of the Times writes that “[Shurin’s] hiring reflected the feeling of the founding editor, Abraham Cahan, that the newspaper needed to speak to the religious Jews who flooded the United States in the 30’s and 40’s.” Indeed, according to Estraikh and Newfield, “Grandfathers,” 75 n. 8, based on an article published in the Forverts in February 1956, “[b]y the mid-1950s, secular readers already belonged to the minority of the Forverts audience.” See also Estraikh, “A Mid-Twentieth-Century Quest,” passim, but esp. pp. 121-122, as well as the comments cited by S. Daniel, editor of Ha-tsofeh, in an article translated as “Faithful Servant” in Shurin, Moadim Lesimcha, xxi-xxiv.

[13] Shurin’s first column appeared as A.B. Rutzon, “‘Mizrakhi’ un ‘agudes yisroel’ – vegn vos zey krigen zikh,” Forverts (November 5, 1944): B3 (Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3475, notes that A.B. Rutzon was one of Shurin’s pseudonyms, a reference to his mother’s name, Ruth). The last article of his that I was able to identify was published April 20, 2007; see the table of contents of that issue here (accessed August 19, 2019). See also Anon., “About the Author,” xv.

Interestingly, Schulman, Leksikon, 90-91, writes that Shurin also managed the Fun folk tsu(m) folk (From People to People) readers’ correspondence section of the paper, although I did not find other references to this point. Also interesting, and curious, is the fact that although Shurin’s passing was mourned at the Kave shtibl and in Der moment (accessed August 19, 2019), I could find no article online in either the Forverts or the Forward reporting his death.

[14] See Anon., “About the Author,” xv; Tidhar, Entsiklopedyah, 3475; and Schulman, Leksikon, 90.

[15] I attempted to be faithful to the originals in transcribing these letters, without adjusting or correcting such features as orthography, vocalization, or punctuation.

[16] We know that he was born 11 Shevat, but the exact year is disputed, with varying accounts claiming it was either 5588 (1828), 5589 (1829), 5593 (1833), 5595 (1835), 5598 (1838), or 5599 (1839). For some of the literature on this issue, see Moses M. Yoshor, He-hafets hayyim: hayyav u-po‘olo, vol. 1 (Tel Aviv: Netsah, 1958), 25 with n. 1; Nathan Kamenetsky, Making of a Godol: A Study of Episodes in the Lives of Great Torah Personalities: Improved Edition, vol. 1, pt. 2 (Jerusalem: P.P. Publishers, 2004), 1106-1108 (Notes and Excursuses 5.1 (2) / Excursus B); and [Dan Rabinowitz], “Chofetz Hayyim[:] His Death, the New York Times and Research Tools,” Seforim Blog (October 31, 2006) (accessed August 19, 2019).

[17] Aaron B. Shurin, “Der ‘khofets khayim’, tsu zayn 150 yorikn geboyrn-yor,” Forverts (January 29, 1988): 13, 27. See also Shurin’s earlier, Hebrew-language reflection on the Hafets Hayyim’s life and works: “He-‘hafets hayyim’ – rabban shel yisra’el,” in Keshet gibborim: demuyyot ba-ofek ha-yehudi shel dor aharon, vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1964), 115-121.

[18] The original Yiddish here reads varte-tsimer, lit., “waiting room”; I take this to refer to the foyer of the home.

[19] The original Yiddish here reads varte-zal, lit., “waiting hall”; I take this to refer to the hallway off the foyer.

[20] The Institute website can be found here, and Dickman’s interview can be found either on the Visual History Archive Online site here or on YouTube here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[21] For three slightly different dappei-ed (pages of testimony) filed by Dickman with Yad Vashem about her father, see 1, 2, and 3; for two she filed about her mother, see 1 and 2; and for two she filed about her grandmother Rose, see 1 and 2 (accessed August 19, 2019).

[22] According to Shemaryahu (Shmerele) Szarafan, “Di religyeze vilne,” in Aaron Isaac Grodzenski (ed.), Vilner almanakh (Vilna: Ovnt Kuryer, 1939; repr. Brooklyn: Moriah Offset Co., 1992), cols. 321-332, at col. 324, the Tiferes Bachurim Society was founded in 1902 by the young Rabbi Jechiel ha-Levi Sruelow (1879–1946) to combat the radical, anti-religious forces on the Jewish street by teaching young workers and craftsmen Torah and Talmud at night and on Shabbat and yom tov, when they had free time. Chaim Bruk was one of the people who did much to ensure the society’s financial security; he is pictured, together with Szarafan, Sruelow, and other members of the board of directors, in Leyzer Ran (ed.), Jerusalem of Lithuania: Illustrated and Documented, vol. 1 (New York: Vilno Album Committee, 1974), 261, and here (accessed August 19, 2019). See also Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin et al. (eds.), “Appendix: Synagogues, Batei Midrash and Kloyzn in Vilnius,” in Synagogues in Lithuania: A Catalogue, vol. 2 (Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, 2012), 281-353, at pp. 303-304 (no. 12), and Yisrael Rozenson, “‘Ba‘avur tse‘irim kemo gam le-ovedim u-le-ozerim ba-hanuyyot’: al ha-mif‘al ha-hinnukhi ‘tif’eret bahurim’ be-vilnah,” Hagut: mehkarim ba-hagut ha-hinnukh ha-yehudi 10 (2014): 15-72, esp. p. 44. The society eventually moved into the former kloyz of the Lubavitcher Hasidim located in the Vilna shulhoyf (synagogue courtyard); see no. 12 in the diagram of the shulhoyf available here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[23] A. Karabtshinski, “Mishmeres-khoylim,” in Grodzenski, Vilner almanakh, cols. 319-320, reports that the society after which the hospital was named was founded by Rabbi Bezalel Altshuler in 1890 as a branch of Vilna’s general charity fund and that the hospital itself was built in 1913. Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, 161, by contrast, writes that the hospital building dedication took place in 1912. See also the photograph of the 1910 cornerstone-laying ceremony on that same page (161) in which, according to Dickman’s interview (watch at approx. 2:49:15), Bruk is pictured on the far right wearing a straw hat and holding a cane. For a photograph of the hospital building before the outbreak of World War II, see here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[24] See Cohen-Mushlin et al., “Appendix,” 317-318 (no. 60). For a photograph of Chaim Bruk praying in the kloyz circa 1935, see Dickman’s interview (watch at approx. 2:50:11); he is pictured on the far right in the first row.

[25] For maps of prewar/wartime Jewish Vilna, see Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, insert (in Yiddish), and here (in Polish) (accessed August 19, 2019). For a modern map of Vilna with Jewish sites (including ghetto borders) overlaid, see here (make sure to click “Explore on your own”) (accessed August 19, 2019). Most of the addresses mentioned above can be found in the vicinity of the two Vilna ghetto locations. For a photograph of a 3-D model of the Vilna ghettos created illegally by Jewish artists in 1943, see Leyzer Ran and Leybl Koriski (eds.), Bleter vegn vilne: zamlbukh (Łódź: Farband fun Vilner Yidn in Poyln, 1947; also available through the New York Public Library Yizkor Book online portal [accessed August 19, 2019]), after p. 52. Finally, for photographs of wartime and present-day Rudnicka/Rūdninkų Street, see here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[26] A definitive academic study of R. Israel Meir ha-Kohen’s life and legacy remains a scholarly desideratum. Rabbi Eitam Henkin, who, together with his wife Naama, was cruelly murdered in October 2015 by Palestinian terrorists, had made a major bid to fill the void by submitting a doctoral proposal on the topic to Tel Aviv University. Henkin’s mentor, Prof. David Assaf, posted the proposal online shortly after his death, both as a memorial for this up-and-coming scholar, whose life and brilliant career were cut all too short, and for the benefit of future researchers: “Sheloshim le-retsah eitam henkin: tokhnit ha-mehkar al ‘he-hafets hayyim’,” Oneg shabbat (October 30, 2015) (accessed August 19, 2019). The most recent attempt of which I am aware to critically assess, albeit partially, the work of the Hafets Hayyim was penned by Benjamin Brown, “Ha-‘ba‘al bayit’: r. yisra’el me’ir ha-kohen, he-‘hafets hayyim’,” in Benjamin Brown and Nissim Leon (eds.), Ha-‘gdoylim’: ishim she-itsevu et penei ha-yahadut ha-haredit be-yisra’el (Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute; Magnes Press, 2017), 105-151.

The most extensive research on the Hafets Hayyim’s life conducted outside the academic sphere is that by Rabbi Moses M. Yoshor (1896–1978), a student and eventual personal secretary of this great Torah sage. For the history of Yoshor’s various biographical studies of his revered teacher, see his The Chafetz Chaim: The Life and Works of Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan of Radin, trans. Charles Wengrov (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1984), xv-xviii, xxvii-xxviii, as well as the unpaginated translator’s note and note on the author in the frontmatter.

[27] On the Hafets Hayyim as one of the main Lithuanian representatives of a phenomenon Benjamin Brown has termed “the return of ‘pure faith’” within the Jewish tradition, see his “Shuvah shel ‘ha-emunah ha-temimah’: tefisat ha-emunah ha-haredit u-tsemihatah ba-me’ah ha-19,” in Moshe Halbertal, David Kurzweil, and Avi Sagi (eds.), Al ha-emunah: iyyunim be-mussag ha-emunah u-be-toledotav ba-massoret ha-yehudit (Jerusalem: Keter, 2005), 403-443, 669-683, at pp. 433-436, as well as idem, “Ha-‘ba‘al bayit’,” 143-146.

[28] See the account of his son, Rabbi Aryeh Leib Poupko (ca. 1860–1938), in Mikhtevei ha-rav hafets hayyim z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah]: korot hayyav, derakhav, nimmukav ve-sihotav, 1st ed. (Warsaw: B. Liebeskind, 1937), 12 (third pagination): “My mother, of blessed memory, told me in my youth that during my upbringing they almost never consulted with doctors. If one of us fell ill, my father advised [my mother] to distribute a pood of bread to the poor, while he ascended to the attic and prayed, and the sickness departed” (par. 26; subsequently quoted in David Falk, Sefer ha-boteah ba-H[ashem] hesed yesovevennu [Jerusalem: n.p., 2010], 92, 250-251). In two other places, Poupko quotes his father as extolling the value of physical suffering in this world as a means of reaching the next world (ibid., 13 [third pagination; pars. 28-29]); see also ibid., 22 (first pagination). Moses M. Yoshor, Saint and Sage (Hafetz Hayim) (New York: Hafetz Hayim Yeshivah Society, 1937), 135, writes that the Hafets Hayyim refused to heed the advice of his physicians when he trekked approximately eighty kilometers from Radin (present-day Radun’, Belarus) to Vilna in early 1932, toward the end of his life, in order to attend a rabbinical conference.

[29] Several sources treat the Hafets Hayyim’s concern for others’ (particularly his students’) physical well-being: Moses M. Yoshor, He-hafets hayyim: hayyav u-po‘olo, vol. 2 (Tel Aviv: Netsah, 1959), 717; ibid., vol. 3 (Tel Aviv: Netsah, 1961), 846-847, 918; and Aryeh Leib Poupko, Mikhtevei ha-rav hafets hayyim z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah], ed. S. Artsi, 2 vols. (Bnei Brak: n.p., 1986), 2:107. In addition, in his magnum opus, Mishnah berurah, the Hafets Hayyim discusses situations in which a doctor’s opinion is accorded halakhic significance, e.g., in the determination of whether someone should fast on Yom Kippur (see his comments to Joseph Caro, Shulhan arukh, Orah hayyim 618).

[30] Strangely, I could not find mention of either Bruk or his son-in-law Mones Margolin in the essays about Vilna doctors by A.J. Goldschmidt and Zemach Shabad in Ephim H. Jeshurin (ed.), Vilne: a zamelbukh gevidmet der shtot vilne (New York: Wilner Branch 367, Workmen’s Circle, 1935), 377-437, 725-736.

[31] In his youth, while in yeshivah, the Hafets Hayyim suffered from a condition that interfered with his learning and was instructed by his doctors to take a break from his studies for a year, which he did (Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 5 [first pagination]). On his consultation with physicians to heal his son Abraham (1869–1891), see ibid., 39 (first pagination); to heal his first wife Frieda (née Epstein), see ibid., 91 (first pagination); and to heal himself, see ibid., 19 (third pagination; par. 46). In the latter connection, see also Yoshor, He-hafets hayyim, 1:66, 3:1058, as well as Dov Katz, Rabbi yisra’el me’ir ha-kohen[,] ba‘al “hafets hayyim”: toledotav, ishiyyuto ve-shittato (Tel Aviv: Avraham Zioni, 1961), 24, 97-98.

Interestingly, Yoshor, He-hafets hayyim, 1:35-36 n. 4, also reports the following ma‘aseh li-setor: Solomon ha-Kohen (1830–1905), a friend of the Hafets Hayyim who grew up in Vilna, became sick between the ages of 13 and 17, and so the doctors instructed him to take a break from learning. He apparently replied that it would be better for him to die from limmud torah than from bittul torah, continued his studies unabated, and was healed. When the Hafets Hayyim would tell this story, he would grow very emotional and repeat his friend’s words several times. Then again, see ibid., 1:343.

As regards Chaim Bruk, a number of sources mention visits by a physician brought in specially from Vilna to treat the Hafets Hayyim, but none of them names him, and it could very well be that different doctors were called upon on different occasions; for instance, we know from Yoshor, He-hafets hayyim, 3:1058, that the Hafets Hayyim would sometimes be treated by Dr. Zemach Shabad (1864–1935). See Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 19 (third pagination); Moses M. Yoshor, Dos lebn un shafen fun khofets khayim, 1st ed., vol. 2 (New York: Moses M. Yoshor, 1937), 481; idem, Saint and Sage, 97; and idem, He-hafets hayyim, 2:614, 624.

[32] See Anon., “Saintly ‘Chofetz Chaim’ Dead; Spiritual Head of World Jewry a Legend in Lifetime; over 100,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (September 15, 1933); (with slight differences:) Anon., “Chofetz Chaim, 105, Is Dead in Poland,” The New York Times (September 16, 1933): 13; and Yoshor, Saint and Sage, 65.

[33] See Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 120 (third pagination; par. 34), 75-76 (fourth pagination; par. 4); Yoshor, Saint and Sage, 131, 175; idem, Dos lebn, 403, 525; and Dov Katz, Tenu‘at ha-musar: toledoteha[,] isheha ve-shittoteha, vol. 4 (Tel Aviv: Avraham Zioni, 1967), 88-89.

Given all of this, it is most surprising, in my opinion, to find the following recorded by the Hafets Hayyim’s son: “Once, when he took ill, he sought to walk to the grave of the ga’on Rabbi Elijah in Vilna and to ask him to arouse heavenly mercy on his behalf, in the merit” of the Haggahot ha-gera that he had printed on Torat kohanim, together with his explanations (vols. 1–2; Piotrków: Mordechai Zederbaum, 1911). See Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 43 (third pagination; par. 83).

[34] In fact, numerous sources testify to the Hafets Hayyim deviating at times from this policy. See Yoshor, Saint and Sage, 97, 108, 256; idem, Dos lebn, 363, 574, 610; Poupko, Mikhtevei, ed. S. Artsi, 2:100-101; and especially Anon., Sefer me’ir einei yisra’el, pt. 2, vol. 2 (Bnei Brak: Ma‘arekhet “Me’ir Einei Yisra’el,” 1999), ch. 28 (pp. 815-868), entitled “The Righteous Man Decrees – The Power of the Hafets Hayyim’s Blessings.” Indeed, even after he published a notice in the Vilna-based Dos vort newspaper in 1925 (not 1927, as some have claimed) requesting that people no longer come to him for blessings due to his weakened state, he would nevertheless warmly greet those who disregarded this plea and grant them their wish. For the text of the announcement, see Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 77 (second pagination; no. 32). See also Yoshor, Dos lebn, 464-465, and Katz, Rabbi, 107-108.

[35] See, e.g., the comments of Tosafot to bKiddushin 81a, s.v. ba‘alah ba-ir ein hosheshin lah mi-shum yihud; David Ibn Zimra, Sh[e’elot] u-t[eshuvot] ha-radbaz, vol. 3 (Warsaw: Mordechai Kalinberg; Josefov: Solomon Zetser, 1882), 18a-b (no. 919 [no. 481]); and Solomon Luria, Yam shel shelomoh mi-massekhet kiddushin (Szczecin: n.p., 1861), 44a (ch. 4, par. 22). This would seem to be the simple read of Moses Maimonides, Mishneh torah, Hilkhot issurei bi’ah 22:1, and of Joseph Caro, Shulhan arukh, Even ha-ezer 22:8, as well.

[36] Of course, the issue of the husbands’ proximity was not the only halakhically relevant factor in this case. For instance, the Hafets Hayyim’s standing in the Jewish world, his location in the apartment relative to where the women were, his elderliness, and the presence of the young Isabella could all have been brought to bear on the question of the permissibility of yihud in this situation. For a summary of some of the discussion, see Eliezer Judah Waldenberg, Sefer she’elot u-teshuvot tsits eli‘ezer, vol. 6 (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1961), 183-190, 228-231 (no. 40, chs. 7-8, 22).

[37] See Rashi to bKiddushin 81a, s.v. ba‘alah ba-ir ein hosheshin lah mi-shum yihud. Several prominent aharonim (following the aforementioned comments of Tosafot ad loc.) interpreted Rashi’s words as prohibiting yihud even when a woman’s husband is in the area. Probably most famously, Rabbi Joel Sirkes (1561–1640) ruled in accordance with this stringent interpretation of Rashi in his Bayit hadash commentary on Jacob ben Asher, Arba‘ah turim, Even ha-ezer 22, s.v. ishah she-ba‘alah ba-ir. Interestingly, Waldenberg, by contrast, read Rashi in a lenient light (and cited others who did so as well); see Sefer she’elot u-teshuvot tsits eli‘ezer, 6:176-177 (no. 40, ch. 4).

[38] See Israel Meir ha-Kohen, Sefer nidhei yisra’el (Warsaw: Meir Jehiel Halter and Meir Eisenstadt, 1893), 62 (ch. 24, par. 6), quoting the Shulhan arukh essentially verbatim. I thank my friend, Jonathan Ziring, for this and a number of the above yihud-related references. If I have missed a relevant citation of the Hafets Hayyim’s own work, I would love to know about it; please message me about this or any other issue with this blogpost here.

[39] As a couple of friends rightly pointed out to me, what impelled the Hafets Hayyim to avoid joining the women in “the innermost rooms” of the apartment may not have been specific halakhic considerations but rather a more general sense of propriety. The interpretation of his behavior as reflecting a reluctance to be “secluded” (aleyn in the original) with the women despite his advanced age relies on the perceptions of someone who was five years old at the time and who may not have appreciated the complexity of the Hafets Hayyim’s thought process.

One historical question raised by the letter for which I have not yet found a satisfying answer concerns the identity of the niece who lived next door to the Bruks and Margolins in Vilna and whom the Hafets Hayyim would regularly visit when he came to town. Some of the basic information on his family tree can be gleaned from Poupko, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 2-3 (first pagination), who informs us that the Hafets Hayyim had a number of half-siblings. See also Binyamin of Petah Tikva, “He-hafets hayyim u-mishpahto,” Toladot ve-shorashim – atsei mishpahah (January 14, 2011) (accessed August 19, 2019) for a more extensive discussion of the Hafets Hayyim’s relations. More research into the various branches of his family is required.

37 thoughts on “A nay bintl briv: Personal Reminiscences of Rabbi Israel Meir ha-Kohen from the Yiddish Republic of Letters”

Thanks so much for this!

I wonder how much the memory of a five year can be trusted, though. For example, was she specifically told that he sat where he did because of the presence of women? Perhaps it was something much more prosaic.

The fact that the Chafetz Chaim had to ask people to stop coming to him for brachot is a good sign he gave them. (Shimon Peres would speak of the bracha he got from the Chafetz Chaim, which had to have been well after 1925.) Many of the mentions of him giving brachot indicate that, as a kohen, he would say Birkat Kohanim (or just “Shalom,” the last word), which halachically is completely uncontroversial.

Looking forward to the second part!

I would think that any scholar even half the worth of the Chafetz Chayiim would not enter an inner room of anyone’s apartment if only women are present, yichud or not.

Maybe people didn’t think that back then.

Maybe people didn’t think that back then.

Here is the Shurin archive on the Rav

http://173.203.154.59/rhsweb/hakirahshurinbrowsedb.asp

Excellent piece, thank you!

I’m pretty sure that the 2 Chaim Lieberman’s were inadvertently mixed up. Chaim Lieberman who worked at the Forverts and had a close relationship with R’ Shurin, was a Yiddish essayist and literary critic, who lived from 1890-1963.

The Chaim Lieberman who was a “famed historian and bibliophile” and lived 1892-1991, was the Raayatz’s legendary gabai.

Thank you again!

As I’ve mentioned here before Hillel Rogoff (our next door neighbor when I was growing up) was an alumnus of Yeshivas Etz Chaim, which gave birth to RIETS, and left after leading a student strike, I believe on behalf of the yeshiva’s staff. Thus his kindling to R’ Shurin is less surprising. Going through R’ Shurin’s articles etc is a marvelous idea. Yasker Koach!

I just want to say I’m very new to blogs and seriously loved you’re page. Likely I’m likely to bookmark your site . You certainly have really good stories. Thanks for revealing your blog site.

I merely picked up your blog post a couple weeks ago i have actually been perusing this tool always. An individual has a lot of helpful tips at this point we absolutely love your lifestyle of a internet sites actually. Stick to the nice perform!

Do you believe reincarnation? Do you think is reincarnation real?

I like it when folks come together and share views. Great website, continue the good work!

This is the right blog for everyone who wishes to find out about this topic. You know so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I personally would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a brand new spin on a subject that has been discussed for decades. Wonderful stuff, just great.

I’ve observed that in the world these days, video games will be the latest phenomenon with children of all ages. There are occassions when it may be out of the question to drag the kids away from the video games. If you want the very best of both worlds, there are lots of educational gaming activities for kids. Interesting post.

MetroClick specializes in building completely interactive products like Photo Booth for rental or sale, Touch Screen Kiosks, Large Touch Screen Displays , Monitors, Digital Signages and experiences. With our own hardware production facility and in-house software development teams, we are able to achieve the highest level of customization and versatility for Photo Booths, Touch Screen Kiosks, Touch Screen Monitors and Digital Signage. Visit MetroClick in NYC at http://www.metroclick.com/ or , 121 Varick St, New York, NY 10013, +1 646-843-0888.

Faytech North America is a touch screen Manufacturer of both monitors and pcs. They specialize in the design, development, manufacturing and marketing of Capacitive touch screen, Resistive touch screen, Industrial touch screen, IP65 touch screen, touchscreen monitors and integrated touchscreen PCs. Contact them at http://www.faytech.us, 121 Varick Street, New York, NY 10013, +1 646 205 3214.

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Thank you!

Hi, I do believe this is a great blog. I stumbledupon it 😉 I will come back once again since i have bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

방문해주세요 https://www.wooricasinokorea.com 달팽이게임

Your style is unique in comparison to other folks I’ve read stuff from. Many thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this blog.

좋아요 https://www.wooricasinokorea.com 더킹카지노

Hey there! I simply would like to give you a big thumbs up for the excellent info you have right here on this post. I am coming back to your web site for more soon.

good https://www.wooricasinokorea.com 우리카지노

This is a topic that is near to my heart… Take care! Where are your contact details though?

A nay bintl briv: Personal Reminiscences of Rabbi Israel Meir ha-Kohen from the Yiddish Republic of Letters – The Seforim Blog

acshysdvkhg

cshysdvkhg http://www.g67t8u1om4444j0bzz5pc9g52d6g2rd2s.org/

[url=http://www.g67t8u1om4444j0bzz5pc9g52d6g2rd2s.org/]ucshysdvkhg[/url]

Cnc Machining Manufacturer

2 Saddle Clamp

Bikini Bathing Suits

Coat Hooks With Shelf

Etched stainless steel sheets

Chemical Storage Cabinet

China Decorative Roman Columns

Disposable Nonwoven Face Mask

You should be a part of a contest for one of the most useful blogs on the web. I am going to recommend this blog!

4 Bits Digital Tube Circuit Board

Bag making & packing machine

Aluminium Side Gusset Packaging Bags

Fiber Cnc Laser Cutting Machine