Kol Nidrei, Choirs, and Beethoven: The Eternity of the Jewish Musical Tradition

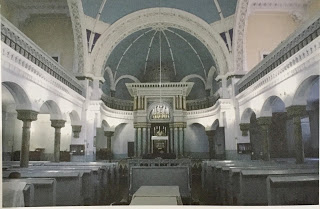

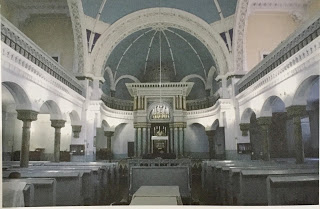

On April 23, 1902, the cornerstone to the Taharat Ha-Kodesh synagogue was laid, and on Rosh Ha-Shana the next year, September 7, 1903, the synagogue was officially opened. The synagogue building was on one of Vilna’s largest boulevards and constructed in a neo-Moorish architectural style, capped with a blue cupola that was visible for blocks. There was a recessed entry with three large arches and two columns. The interior housed an impressive ark, located in a semi-circular apse and covered in a domed canopy. But what really set the synagogue apart from the other 120 or so places to pray in Vilna was that above the ark, on the first floor, were arched openings that served the choir. In fact, it was generally referred to by that feature and was known as the Choral Synagogue. The congregants were orthodox, most could be transported to any modern Orthodox synagogue and they would indistinguishable, in look – dressing in contemporary styles, many were of the professional class, middle to upper middle class, and they considered themselves maskilim, or what we might call Modern Orthodox.

[1]

The incorporation of the choir should be without controversy. Indeed, the Chief Rabbi of Vilna, Yitzhak Rubenstein would alternate giving his sermon between the Great Synagogue, or the Stut Shul [City Synagogue], and the Choral Synagogue.[2] Judaism can trace a long relationship to music and specifically the appreciation, and recognition of the unique contribution it brings to worship. Some identify biblical antecedents, such as Yuval, although he was not specifically Jewish. Of course, David and Solomon are the early Jews most associated with music. David used music for religious and secular purposes – he used to have his lyre play to wake him at midnight, the first recorded instance of an alarm clock. Singing and music was an integral part of the temple service, and the main one for the Levite class who sang collectively, in a choir. With the destruction of the temple, choirs, and music, in general, was separated from Judaism. After that cataclysmic event, we have little evidence of choirs and even music. Indeed, some argued that there was an absolute ban on music extending so far as to prohibit singing.

It would not be until the early modern period in the 16th century that choirs and music began to play a central role in Jewish ritual, and even then, it was limited – and was associated with modernity or those who practiced a more modern form of the religion.

Rabbi Leon (Yehudah Aryeh) Modena (1571-1648) was one of the most colorful figures in the Jewish Renaissance. Born in Venice, he traveled extensively among the various cities in the region.

[3] He authored over 15 books, and made his living teaching and preaching in synagogues, schools, and private homes; composing poems on commission for various noblemen; and as an assistant printer. In 1605, he was living in Ferrara where an incident occurred in the synagogue that kickstarted the collective reengagement with music. Modena explained that “we have six or eight knowledgeable men, who know something about the science of song, i.e. “[polyphonic] music,” men of our congregation (may their Rock keep and save them), who on holidays and festivals raise their voices in the synagogue and joyfully sing songs, praises, hymns and melodies such as Ein Keloheinu, Aleinu Leshabeah, Yigdal, Adon Olam etc. to the glory of the Lord in an orderly relationship of the voices according to this science [polyphonic music]. … Now a man stood up to drive them out with the utterance of his lips, answering [those who enjoyed the music], saying that it is not proper to do this, for rejoicing is forbidden, and song is forbidden, and hymns set to artful music have been forbidden since the Temple was destroyed.

[4]

Modena was not cowed by this challenge and wrote a lengthy resposum to defend the practice which he sent to the Venetian rabbinate and received their approbation. But that did not put the matter to rest.

In 1610, as he approached forty, Modena received his ordination from the Venetian rabbis and settled in Venice to serve not only as a rabbi but as a cantor, with his pleasant tenor voice. In around 1628 in the Venetian ghetto, an academy of music was organized with Modena serving as the Maestro di Caeppella . Both in name and motto that academy embraced its subversive nature. It was called the Academia degli Impediti, the Academy of the Hampered, named in derision of the traditional Jewish reluctance to perform music because of “the unhappy state of captivity which hampers every act of competence.” In this spirit, especially in light of Modena’s responsum on music in 1605, the Accademia took the Latin motto Cum Recordaremur Sion, and in Hebrew, Bezokhrenu et Tzion, when we remembered Zion, based paradoxically on Psalm 137, one of the texts invoked against Jewish music: “We hung up our harps…. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?”

On Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah in October 1628, a spectacular musical performance was held in the Spanish synagogue, which had been decorated with silver and jewels. Two choirs from the academy sang artistic Hebrew renderings of the afternoon service, the evening service, and some Psalms. Their extensive repertoire lasted a few hours. A throng of Christian noblemen and ladies attended the Simchat Torah service. The applause was great, and police had to guard the gates to ensure order

Beyond his musical endeavors, Modena also served as an expert in Hebrew publishing. The two would create a confluence that enabled the first modern Jewish book of music.

For Rabbi Leon Modena, his young friend, the musician Salamone Rossi, would herald the Jewish re-awakening. We know very little about Rossi’s life. He was born circa 1570 and died sometime after 1628, possibly in 1630. He is listed as a violinist and composer on the payroll of the Gonzaga dukes, rulers of Mantua, and was associated with a Jewish theater company, as composer or performer or both. In addition, Rossi was also writing motets – short pieces of sacred music typically polyphonic and unaccompanied – for the synagogue using contemporary Italian and church styles. He was specifically encouraged in this endeavor by Modena, who urged the composer to have this music published so that it could have an even greater impact.

[5] In 1622 the publishing house of Bragadini in Venice issued thirty-three of Rossi’s synagogue motets in a collection,

Shirim asher le-Shlomo, that Modena edited. This extraordinary publication represented a huge innovation. First, the use of musical notations that required a particularly thorny issue to be resolved right versus left. Rossi decided to keep the traditional musical notational scheme and provide those from left to right and write the Hebrew backward, because the latter would be more familiar to the reader. Second, it was the first time the Hebrew synagogue liturgy had ever been set as polyphonic choral music. Polyphony in the Christian church had begun centuries earlier. Rossi’s compositions sound virtually indistinguishable from a church motet, except for one thing: the language is Hebrew – the lyrics are from the liturgy of the synagogue, where this music was performed.

There was bound to be a conflict between the modern Jews who had been influenced by the Italian Renaissance and who supported this innovation, and those with a more conservative theology and praxis. But the antagonism towards music, especially non-traditional music, remained strong. Anticipating objections over Rossi’s musical innovations, and perhaps reflecting discussions that were already going on in Venice or Mantua, Modena wrote a lengthy preface included the responsum he wrote in 1605 in Ferrara in support of music in which he refuted the arguments against polyphony in the synagogue. “Shall the prayers and praises of our musicians become objects of scorn among the nations? Shall they say that we are no longer masters of the art of music and that we cry out to the God of our fathers like dogs and ravens?”3 Modena acknowledged the degraded state of synagogue music in his own time but indicates that it was not always so. “For wise men in all fields of learning flourished in Israel in former times. All noble sciences sprang from them; therefore, the nations honored them and held them in high esteem so that they soared as if on eagles’ wings. Music was not lacking among these sciences; they possessed it in all its perfection and others learned it from them. … However, when it became their lot to dwell among strangers and to wander to distant lands where they were dispersed among alien peoples, these vicissitudes caused them to forget all their knowledge and to be devoid of all wisdom.”

In the same essay, he quotes Emanuel of Rome, a Jewish poet from the early fourteenth century, who wrote, “What does the science of music say to the Christians? ‘Indeed, I was stolen out of the land of the Hebrews.’” Using the words of Joseph from the book of Genesis, Modena was hinting that the rituals and the music of the Catholic church had been derived from those of ancient Israel, an assertion that has been echoed by many scholars. Although it can be argued that Modena indulges in hyperbole, both ancient and modern with some attributing the earliest ritual music to Obadiah the convert who noted a Jewish prayer that was only then appropriated for use in Gregorian chants.

[6]

Directly addressing the naysayers, Modena wrote that “to remove all criticism from misguided hearts, should there be among our exiles some over-pious soul (of the kind who reject everything new and seek to forbid all knowledge which they cannot share) who may declare this [style of sacred music] forbidden because of things he has learned without understanding, … and to silence one who made confused statements about the same matter. He immediately cites the liturgical exception to the ban on music. Who does not know that all authorities agree that all forms of singing are completely permissible in connection with the observance of the ritual commandments? … I do not see how anyone with a brain in his skull could cast any doubt on the propriety of praising God in song in the synagogue on special Sabbaths and on festivals. … The cantor is urged to intone his prayers in a pleasant voice. If he were able to make his one voice sound like ten singers, would this not be desirable? … and if it happens that they harmonize well with him, should this be considered a sin? … Are these individuals on whom the Lord has bestowed the talent to master the technique of music to be condemned if they use it for His glory? For if they are, then cantors should bray like asses and refrain from singing sweetly lest we invoke the prohibition against vocal music.

No less of an authority than the Shulhan Arukh, explains that “when a cantor who stretches out the prayers to show off his pleasant voice, if his motivation is to praise God with a beautiful melody, then let him be blessed, and let him chant with dignity and awe.” And that was Rossi’s exact motivation to “composed these songs not for my own honor but for the honor of my Father in heaven who created this soul within me. For this, I will give thanks to Him evermore.” The main thrust of Modena’s preface was to silence the criticisms of the “self-proclaimed or pseudo pious ones” and “misguided hearts.”

Modena’s absurdist argument – should we permit the hazzan to bray like an ass – is exactly what a 19th-century rabbi, Rabbi Yosef Zechariah Stern, who was generally opposed to the Haskalah – and some of the very people who started the Choral Synagogue, espoused. Stern argues that synagogal singing is not merely prohibited but is a cardinal sin. To Stern, such religious singing is

only the practice of non-Jews who

“strive to glorify their worship in their meeting house [בית הכנסת שלהם] so that it be with awe, and without other intermediaries that lead to distraction and sometimes even to lightheadedness. In the case of Jews, however, there is certainly be a desecration of G-d’s Name when we make the holy temple a place of partying and frivolity and a meeting house for men and women … in prayer. there is no place for melodies [נגונים], only the uttering of the liturgy with gravity [כובד ראש] … to do otherwise is the way of arrogance, as one who casts off the yoke, where the opposite is required: submission, awe and gravity, and added to this because of the public desecration of G-d’s Name – a

hillul ha-Shem be-rabbim.” (For more on this responsum see

here.)

Similarly, even modern rabbis, for example, R. Eliezer Waldenberg, who died in 2006, also rejected Modena’s position, because of modernity. Although in this instance, not because of the novelty or the substance of Modena’s decision but because of the author’s lifestyle. Modena took a modern approach to Jewish life and was guilty of such sins as not wearing a yarmulke in public and permitting ball playing on Shabbos.

Despite these opinions, for many Orthodox Jews, with some of the Yeshivish or Haredi communities as outliers, song is well entrenched in the services, no more so than on the Yomim Noraim. Nor is Modena an outlier rabbinic opinion of the value of music and divine service. No less of an authority than the Vilna Gaon is quoted as highly praising music and that it plays a more fundamental role to Judaism that extends well beyond prayer. Before we turn to the latter point it is worth noting that at times Jewish music was appropriated by non-Jews – among the most important composers, Beethoven. One the holiest prayer of Yom Kippur, Kol Nedri, is most well-known not for the text (which itself poses many issues) but the near-universal tune. That tune, although not as repetitive in the prayer can be heard in the sixth movement of Beethoven’s Quartet in C# minor, opus 131 (you can hear a version

here). One theory is in 1824, the Jews in Vienna were finally permitted to build their own synagogue and for the consecration asked Vienna’s most famous composer to write a piece of music.

[7] Although Beethoven did not take the commission, he may have done some research on Jewish music and learned of this tune. We could ask now, is Beethoven playing a Jewish music?

[8]

R. Yisrael M’Sklov, a student of the Gaon records that he urged the study of certain secular subjects as necessary for the proper Torah study, algebra and few other, but “music he praised more than the rest. He said that most of the fundamentals and secrets of the torah … the Tikkunei Zohar are impossible to understand without music, it is so powerful it can resurrect the dead with its properties. Many of these melodies and their corresponding secrets were among the items that Moshe brought when he ascended to Sinai.”

[9]

In this, the Gaon was aligned with many Hassidim who regularly incorporated music into their rituals, no matter where the origin. Just one of many examples, Habad uses the tune to the French national anthem for the prayer

Aderet ve-Emunah. The power of music overrides any considerations of origin. Indeed, they hold that not only can music affect us, but we can affect the music itself, we hold the power to transform what was impure, the source and make it pure. That is not simply a cute excuse, but the essence of what Hassidim view the purpose of Judaism, making holy the world. Music is no longer a method of attaining holiness, singing is itself holiness.

[10]

Today in Vilna, of the over 140 places of worship before the Holocaust five shul buildings remain and only one shul is still in operation. That shul is the Choral Synagogue – the musical shul. Nonetheless not all as it should be. In the 1960s a rabbi from Israel was selected as the rabbi for the community and the shul. When he arrived, he insisted that choirs have no place in Judaism and ordered the choir arches sealed up. We, however, have the opportunity, as individuals and community to use the power of music to assist us on the High Holidays – that can be me-hayeh ma’tim.

[1] See Cohen-Mushlin,

Synagogues in Lithuania N-Z, 253-61. For more on the founding of the congregation see Mordechai Zalkin, “Kavu le-Shalom ve-ain: Perek be-Toldot ha-Kneset ha-Maskili ‘Taharat ha-Kodesh be-Vilna,” in

Yashan mi-Pnei Hadash: Mehkarim be-Toldot Yehudei Mizrah Eiropah u-ve-Tarbutam: Shai le-Imanuel Etkes, eds. David Asaf and Ada Rapoport-Albert (Jerusalem: Merkaz Zalman Shazar, 2009) 385-403. The images are taken from Cohen-Mushlin.

[2] Hirsz Abramowicz,

Profiles of a Lost World (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999), 293.

[3] Regarding Modena see his autobiography, translated into English,

The Autobiography of a Seventeenth Century Rabbi, ed. Mark Cohen (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988); and the collection of articles in

The Lion Shall Roar: Leon Modena and his World, ed. David Malkiel,

Italia, Conference Supplement Series, 1 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press, 2003).

[4] His responsum was reprinted in Yehuda Areyeh Modena,

She’a lot u-Teshuvot Ziknei Yehuda, ed. Shlomo Simonsin (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1956), 15-20.

[5] See generally Don Harrán,

Salamone Rossi: Jewish Musician in Late Renaissance Mantua (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999);

Michelene Wandor, “Salamone Rossi, Judaism and the Musical Cannon,”

European Judaism 35 (2002): 26-35; Peter Gradenwitz,

The Music of Israel: From the Biblical Era to Modern Times 2nd ed. (Portland: Amadeus Press, 1996), 145-58.

The innovations of Rossi and Modena ended abruptly in the destruction of the Mantua Ghetto in 1630 and the dispersion of the Jewish community. The music was lost until the late 1800s when Chazzan Weintraub discovered it and began to distribute it once again.

[6] See Golb who questions this attribution and argues the reverse and also describes the earlier scholarship on Obadiah. Golb, “The Music of Obadiah the Proselyte and his Conversion,”

Journal of Jewish Studies 18: 43-46.

[7] Such ceremonies were not confined to Austria. In Italy since the middle of the seventeenth century, special ceremonies for the dedication of synagogues had become commonplace. See Gradenwitz,

Music of Israel, 159-60.

[8] Jack Gotlieb,

Funny, It Doesn’t Sound Jewish, (New York: State University Press of New York, 2004), 17-18; see also Theodore Albrecht, “Beethoven’s Quotation of

Kol Nerei in His String Quartet, op. 131: A Circumstantial Case for Sherlock Holmes,” in

I Will Sing and Make Music: Jewish Music and Musicians Through the Ages, ed. Leonard Greenspoon (Nebraska: Creighton University Press, 2008), 149-165. For more on the history of the synagogue see Max Grunwald,

Vienna (Philadephia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1936), 205-21.

[9] R. Yisrael M’Sklov,

Pat ha-Shulhan (Sefat, 1836).

[10] See Mordechai Avraham Katz, “Be-Inyan Shirat Negunim ha-Moshrim etsel ha-Goyim,”

Minhat ha-Kayits, 73-74. However, some have refused to believe that any “tzadik” ever used such tunes. Idem. 73. See also our earlier article discussing the use of non-Jewish tunes “

Hatikvah, Shir HaMa’a lot, & Censorship.”

3 thoughts on “Kol Nidrei, Choirs, and Beethoven: The Eternity of the Jewish Musical Tradition”

A big thank you for your article.

These are actually great ideas in concerning blogging.

win money video gaming