An Incident of “Pilegesh B’Givah” in 19th Century Germany

AN INCIDENT OF “PILEGESH B’GIVAH” IN 19TH CENTURY GERMANY

by Eli Genauer

I recently purchased an antique Hebrew book for less than the price of a dinner at a moderately priced restaurant. This particular edition is what some would call a “common” — meaning it is the 36th edition (the fourth edition of a revised version) of this book and it was printed in the mid-19th century. Generally, the market does not assign a high price for books like these, but they can be a treasure trove of knowledge and information.

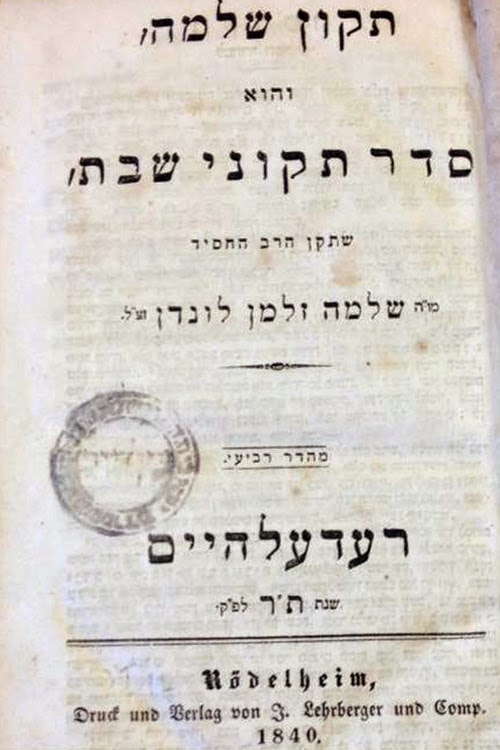

The work is Tikkun Shlomo and is primarily focused on the Shabbos liturgy. I reproduced the title page:

Many will no doubt recognize the name of the compiler, Shlomo Zalman London (1661-1748) who wrote the book “קהלת שלמה”and that it was reprinted thirty times in the next 200 years.

Tikkun Shlomo was first published in Amsterdam by Dr. Naftali Hertz HaLevi in 1733. Dr. Levi published many a storied book, including the first edition of Mesilat Yesharim and the edition of the Shu”t HaTashbetz that is alleged (erroneously) to have been cosigned to flames. According to Friedberg, when Dr. Levi published the Tikun Shlomo, not much else was being published in Amsterdam due to the effect of the Thirty-Year War.[1] The Tikkun Shlomo was very popular, going through almost 40 editions by the late 19th century. Heidenheim expanded this work in 1835, and the edition I purchased was the fourth Heidenheim edition (two of the three were published in Roedelheim and the other in Lemberg).

Things get off to a wonderful start in this book with the Hakdamah which is indicated to come from the third edition. In it, the unnamed editor pays tribute to his mentor Wolf Heidenheim Z”L and maintains that he has followed in his footsteps in all matters because “anyone who follows him will not err”. The editor only refers to himself at the end of the Hakdamah as “HaTzair”, but he leaves us an unmistakable hint as to his identity. Before we get to that, let us see what else he includes in this “Hakdamah”

ויהי מימים,ויקם עוד בּישׂראל פּורץ גדר,וישׁחת דברים נעימים, ויוסף עוד להרוס חומת שׂפת עבר ולדבּר תועה אשר לא כּדת. כּי פּרץ מצפון בא בא, ותפתח הרעה, וידפיס אישׁ אחד את המחזורים ב׳האננאפער׳, ויעבור חק, ויהפוך וישׁנה מדעתו את דברי התפילות ופיוטים, ויעקש ויעקל מאוד כמעט בכל דף ודף, ותהי זמירת ישׂראל בידו מעין משחת ומקור נרפשׁ, אשה יפה וסרת טעם, כּי שנה את טעמה ויתעמר בה וימכרה בּכּסף, וכן לא יעשׂה.

He takes great offense to a certain Machzor printed by “one man”. The Machzor to which he referring to is known as “Ordnung der Oeffentlichen Andacht für die Sabbath und Festtage des Ganzen Jahres, nach dem Gebrauche des Neuen Tempel-Vereins”, otherwise known as “Seder ha-‘Abodah, Minhag Ḳehal Bayit Ḥadash” printed in Hamburg (not Hanover) in 1819. Two editors are listed: Seckel Isaac Fraenkel and Meyer Israel Bresslau. It was the new prayer book of the Hamburg Reform Temple dedicated in 1818. To paraphrase what he writes about this effort: “ a great evil has descended from the north, one that has been perpetrated by a man who published Machzorim in the city of Hanover ( Hamburg ). In his hands, the prayers, which are like a beautiful woman , are now left with no personality. His purpose was to destroy the Hebrew language, the prayers as we know them, and Judaism itself.”

He continues by writing that he has authored a work Zichron Livnei Yisroel ( Altona 1819) in which he lays out his war against these Machzorim.[2] The title incorporates this explanation:

זה ימים יצא בדפוס קונטרס מיוחד לתפילת ערבית ושחרית לשבת, ומעתיקי תפלה הזאת עברו גבול אשר גבלו הראשונים, גרעו והוסיפו כחפץ לבבם … חלילה … לשנות מסדר תפלתינו / … דברי … עקיבא בר”א ברעסלויא, ראב”ד פה ק”ק אלטונא

This was Rabbi Akiva Wertheimer (1778-1835), the Rav of Altona, Germany, today part of the city of Hamburg. He wrote “Zichron Livnei Yisroel” and was the editor of our edition of “Tikun Shlomo”. His opposition to the new Reform prayer service is noted in a book called “Shnos Dor V’Dor” printed in Jerusalem by Artscroll/Mesorah in 2004. It records the following that occurred in 1819 which coincides with the printing of his book “Zichron Livnei Yisroel”:

בשנת תקע״ט, עוד קודם להתמנורנו, בקום המחדשים ״אנשי ההיכל״

הרפורמי דהמבורג לשנות את סדרי התפילה היה הוא הראשון אשר יצא כנגדם והזהיר את כל הקהילות סביבות אלטונא מפניהם.

Continuing in the Hakdamah to Tikun Shlomo, we find that Rav Wertheimer has launched a campaign against the reformers by adding that he has sent this out broadside everywhere to warn others of this assault on tradition. He does this brilliantly by paraphrasing a Pasuk in Tanach ( Shoftim 20:6) which deals with the tragic story of “Pilegesh B’Givah” an incident which almost tore the Jewish people apart.

The Pasuk reads: וָאֹחֵז בְּפִילַגְשִׁי, וָאֲנַתְּחֶהָ, וָאֲשַׁלְּחֶהָ, בְּכָל-שְׂדֵה נַחֲלַת יִשְׂרָאֵל: כִּי עָשׂוּ זִמָּה וּנְבָלָה, בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל.

His paraphrase reads:

ואוחז בפּילגשׁו ואנתחה ואשׁלחה בכל גבול ישׂראל, למען יראו זקני עם וקציניו, והסירו גם את המכשלה הזאת מקרבּם

The full text of the broadside was published in Dukes, AW”H leMoshav, Cracow: 1903, 104-05. Additionally, the National Library of Israel has a copy (perhaps that of Israel Mehlman, see his catalog Ginzei Yisrael, no. 1743). The broadside is signed, Akiva br”a Bresslau without additional identifiers, i.e. the son of Avigdor Wertheimer. As Dukes notes, Graetz mistakenly attributed this work to a different Akiva, Akiva Eiger. But he was not the only one to publish against the Hamburg Temple and its prayer book in Altona that year. The work, Eleh Divrei ha-Brit, was also published in Altona in 1819 and it contains, among others, the position of the Hatam Sofer.

The battle was waged by both sides, and Meyer Israel Bresslau, one of the editors of the Hamburg prayer book, that same year responded with Herev Nokmat (available online here). The other editor, Fraenkel, in the prayerbook includes a defense of the changes[3].

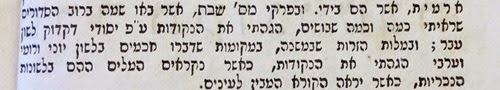

As with many editors of Siddurim, Rav Wertheimer extols the exactness of his edition, claiming that he has fixed many of the errors that have crept into previous Siddurim. Specifically, he addresses the text of Mishnayos Shabbos which appeared in many Siddurim and which he has carefully edited especially when it comes to the “Nekudos”.

He continues and states that when it comes to words of foreign origin, such as in Greek, Latin or Arabic, he has also made sure that the “Nekudos” are correct reflecting the proper pronunciation in those languages.

Unfortunately this is not a simple task and this example will illustrate the difficulty in doing so.

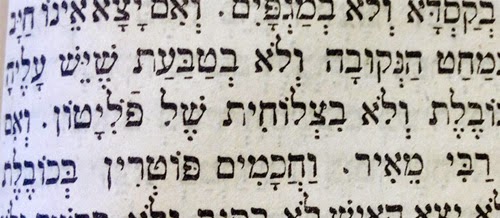

The laws of what a woman may or may not carry outside on Shabbos are discussed in Shabbos 6:3. Among the items prohibited is something called a “Tzlochis Shel Palyiton”, a flask of “Palyiton.” Jastrow defines this word as “an ointment or oil prepared from the leaves of spikenard”. He adds that its origin is the Latin word “foliatum”. The Latin Lexicon website spells this word foliātum and gives the exact same definition. So how should this Latin word be spelled in Hebrew?

Rav Wertheimer indicates that it should be pronounced something like “Folia’tone”which is pretty close to the Latin word except for there being an “n” sound at the end of the word instead of the “m” sound.

I have a Mishnayos printed in Pisa during the same time period (1797) which makes it look more like “Pal’yi’tone”:

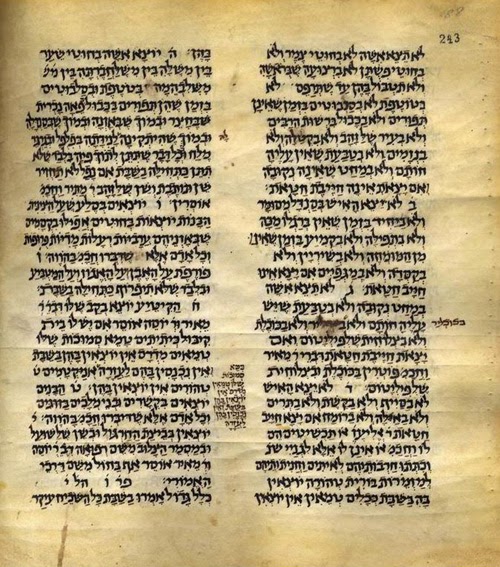

Two very old manuscripts of the Mishneh shed some light on how the word was originally spelled. One of the most famous is known as Codex Kaufmann ( MS Kaufmann A 50) which was written in 10th or 11th century Palestine. There we find the word looking more like “Pil’Ya’Tome”, with an “m” sound at the end:

The Parma manuscript referred to as MS Parma, De Rossi 138 written in 1073 has it the same as Kaufmann.

In recently printed Mishnayos such as from Feldheim, Artscroll, Steinsaltz, and Blackman, the word is spelled “פלייטון” with either a Patach ,Chirik, or “Shva” under the “Peh”, or “פולייטון”, which looks more like Rav Wertheiner’s rendering.

One thing is clear- it is sometimes very difficult to write a foreign word with Hebrew letters and vowels, and it is also difficult to ascertain which version is “correct”.

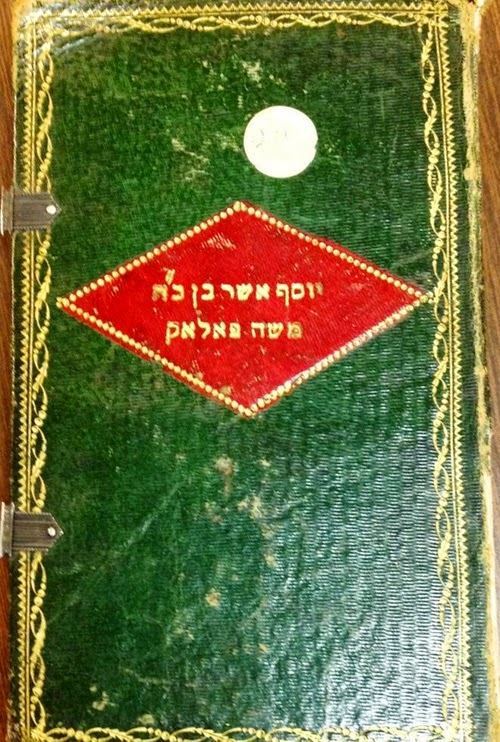

Another wonderful aspect to the book that I bought was learning about the man whose name is embossed on the front cover. He is listed as יוסף אשר בן כ״ה (כבוד הרב) משה פאלאק

We know a bit about Yosef Asher Pollock from some of the other books and manuscripts he owned. The following two citations are from the online catalogue of the Israel National Library:

1. A manuscript written in the 19th century by Chaim ben Yaakov Abolofia.

תקנות קהלת איזמיר.

Los Angeles – University of California 960 bx. 1.9

ותו הספר: “מספרי יוסף אשר פאלאק ז”ל” משנת תרפ”ה.

From this record we know that he had passed away before 1925 and that the manuscript is now in Los Angeles.

2. A manuscript written in the 18th century

(ספר הכונות (חלק שבת ומועדים.

Amsterdam – Universiteitsbibliotheek MS Rosenthal 567

בראשו תו ספר של הבעלים “יוסף אשר פאלאק

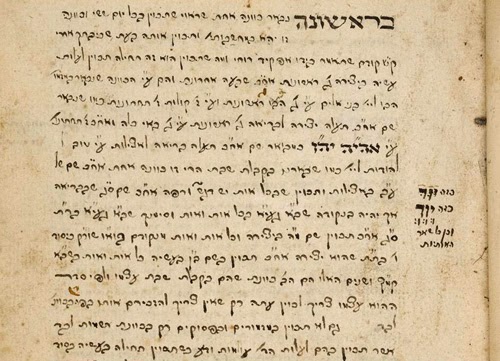

This rare manuscript has been scanned and is available online. The first page looks like this:

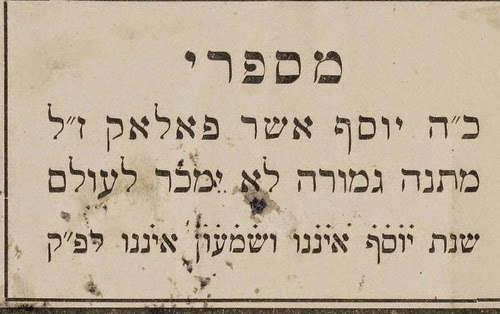

From this one we also learn quite a bit more about Yosef Asher Pollock because it contains this bookplate on the inside front cover

We surmise from here that this was not the only book he had that was donated, as someone went to a lot of trouble composing and printing such a heartfelt donation plate. (“ Yosef is not here, nor is Shimon”) The year the bookplate was printed was 5693(1933). There is also a stern warning that since this is a gift, it may never be sold by the recipient.

The history of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in Amsterdam is also interesting, especially how the collection of Judaica survived the Nazi occupation. The library’s website notes the following:

“The Germans closed the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in the summer of 1941 and transported part of the collection to Germany, where it was earmarked for Rosenberg’s ‘Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage’.

Happily, these plans were thwarted with the German capitulation. Most of the boxes of books were in storage in Hungen, near Frankfurt am Main, where they were found and shipped back to Amsterdam. But the curator and his assistant together with their families had also been deported-for them there was no return”

Happily, these plans were thwarted with the German capitulation. Most of the boxes of books were in storage in Hungen, near Frankfurt am Main, where they were found and shipped back to Amsterdam. But the curator and his assistant together with their families had also been deported-for them there was no return”

Finally, it seems clear to me that my book was also a gift never to be sold. I surmise this from the fact that the name of Yosef Asher Pollack is beautifully embossed on the front cover of the Siddur, making it unnecessary to have an ownership bookplate inside the Siddur.

Nevertheless, on the inside front cover there is a rectangular remnant of a bookplate which has been torn off.

Coincidentally, its size exactly matches the bookplate of the manuscript donated to the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, which contained the admonition of not selling the book. Tearing off this “warning label” enabled the book to be sold, something that most likely happened over time to many books that were donated to libraries.

___________________________________________________

___________________________________________________

[1] Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography, Antwerp: 1937, 49. Although Dr. Levi’s production may have slowed, the bases for Freidberg’s assertion that Amsterdam publishing was affected by the Thrity-Year War is uncertain. During the 18th century, production of Hebrew books in Amsterdam ranges from 82 to a high of 246 per decade. The 1730s, the period that Tikkun Shlomo was published, is in the mid-range of those two extremes, with 145 books published between 1730-39.

[2] This work is a single sheet broadside and begins with Moda’ah raba . . . Zikhron Le-veni Yisrael.

[3] For a summary of his arguments, see Petuchowski, Prayerbook Reform in Europe, New York, NY: 1968, 53-54.

[2] This work is a single sheet broadside and begins with Moda’ah raba . . . Zikhron Le-veni Yisrael.

[3] For a summary of his arguments, see Petuchowski, Prayerbook Reform in Europe, New York, NY: 1968, 53-54.