Today, censorship of Hebrew books takes place on many levels. Although previously the censorship of Hebrew books was driven in large part due to external concerns, today, most of the censorship takes place internally, by Jews for Jews. This censorship is generally driven by the false notion that Orthodox Judaism is and was monolithic. Of course, students of history know that this is entirely false; within the confines of Orthodoxy, there was diversity of opinion and practice (perhaps due to modern day censorship, this diversity has been slowly eroding within the Orthodox community).

It’s worth noting that one of the more insidious examples of censorship is that of the modern Hebrew book databases. Today, there are three distinct databases, although they each borrow from one another.[1] The three are Otzar HaHochma, Otzrot ha-Torah and Hebrewbooks.org. The first two are more explicit about their censorship of some texts. They provide options when purchasing their databases, a scrubbed version and a more complete version. Some refer to the scrubbed version as the “Benei Yeshiva” version. It is unclear why those in Yeshiva, presumably dedicating their time to the study of Jewish literature, became short hand for a database that refuses to allow large portions of Jewish literature to be seen. In all events, these at least clue the buyer or user in on the fact that the databases may be incomplete.

Hebrewbooks, however, is in a different category. Hebrewbooks, which is funded by donations, states that its “goal is to bring to life the many Seforim that were written and unfortunately forgotten, and to make all Torah Publications free and ubiquitous.” (Emphasis added). In truth, not all Torah publications are included in the Hebrewbooks database. This is not a product of happenstance that these authors are left out. To the contrary, in many instances, these works were scanned, uploaded and included in the Hebrewbooks database, only to have them disappear when presumably someone decided that these books should be removed. To be clear – Hebrewbooks will take the time, money and effort to make a Torah publication available online, only to remove it – without ever offering a reason or noting that it has been removed.[2] While Hebrewbooks is a modern day example using modern technology to advance a particular ideology, such ideological censorship, especially regarding R. Kook, has and still takes place.[3]

Regarding censorship, one person who has suffered terribly is R. Kook.[4] And, while one can debate the legacy of his philosophy,[5] it is hard to do so when all vestiges of him are removed. Ironically, some of the censorship of R. Kook is partially cured by Hebrewbooks’ inclusion of many of the originals that include comments or portions from R. Kook that no longer appear in the current editions. [Of course, one hopes that the censor at Hebrewbooks doesn’t read this and “remedy” this.] While R. Kook has been censored in various ways, from not mentioning his name, even when it’s merely a reference to a publishing house bearing his name and is not actually a reference to R. Kook (

see here), the most common form of censoring R. Kook is to remove his approbation from works, and there are many, for he was a renowned ga’on in his time. One such work is the excellent and erudite commentary on Torah,

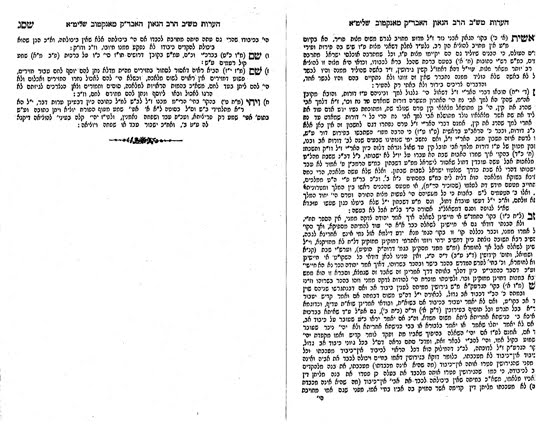

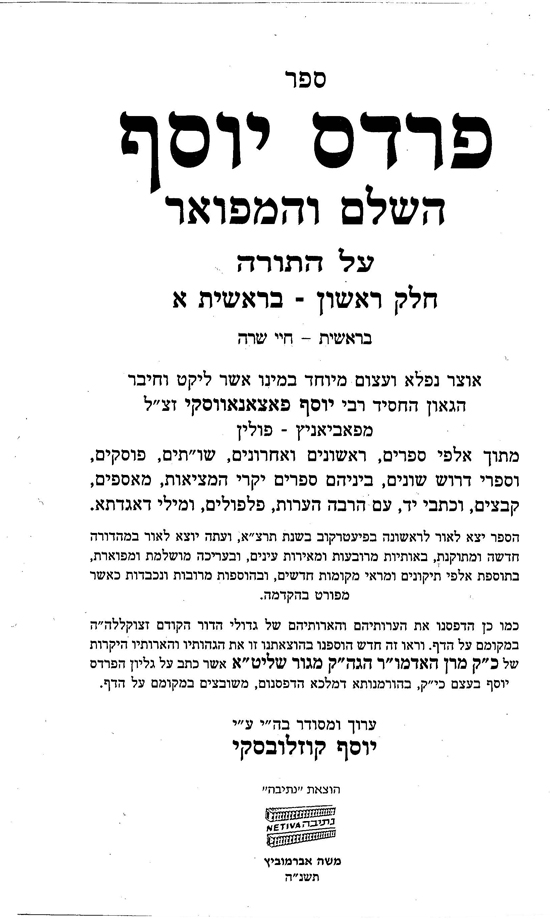

Pardes Yosef by R. Yosef Pazanavski. Although

Pardes Yosef is described as a Torah commentary, in reality is a veritable encyclopedia of highly interesting Rabbinic miscellany. For comparison,

Pardes Yosef is what a Torah commentary would look like if R. Ovadiah Yosef wrote one. It is full of interesting tangents that are treated in an incredibly comprehensive manner. Indeed, many speakers and modern day commentaries appear to be heavily based upon

Pardes Yosef even if it’s not always cited.

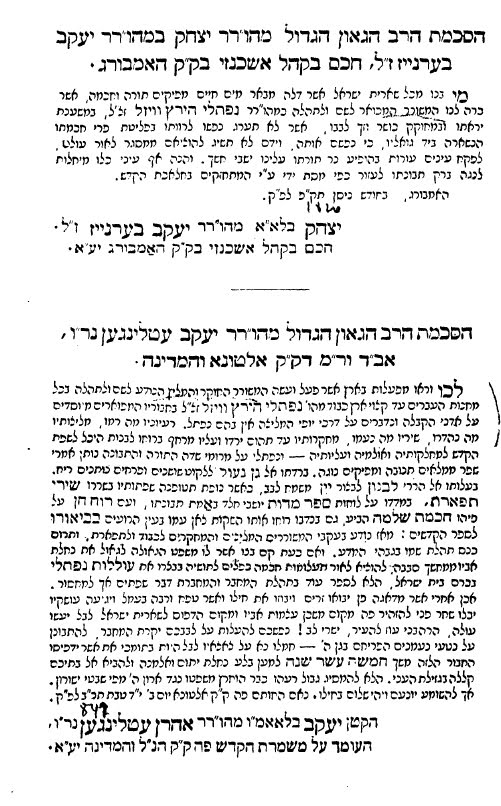

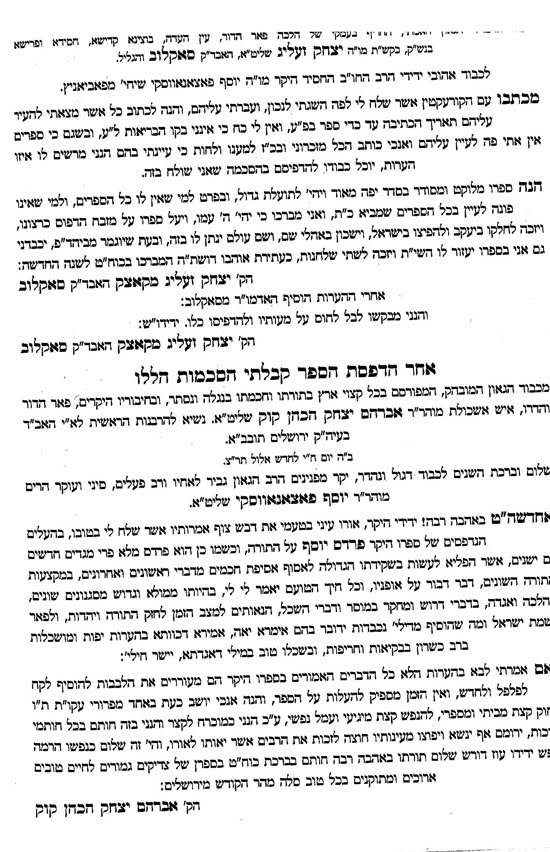

The first volume, on Bereshit, was first published in Lodz in 1930.[6] This work contains the approbations of many well-known Rabbis, including R. Menachem Mendal of Gur (Gur [Gerrer] Rebbi – Penei Menachem), R. Yosef Hayyim Sonnenfeld, R. Meir Shapira, R. Yisrael Meir ha-Kohen (Hafetz Hayyim). In this instance, unlike the case for many approbations, many of those praising the work actually read it, indeed many include glosses and notes on the text. R. Pazanavski was especially proud of the Gur Rebbi’s approbation as R. Pazanavski was a Gur hassid.[7] Now, not everyone seems to have gotten their approbation back to R. Pazanavski in time to include it at the beginning of volume, instead, R. Pazanavski includes some late-received approbations at the end of the book, one of which is R. Kook’s. R. Pazanavski prefaces R. Kook’s approbation with the following:

From the true Gaon, who is known throughout the world for his wisdom and Torah in both the revealed and hidden Torah, and his many precious works, the glory of our generation, the polymath our leader and Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak ha-Kohen Kook shlit”a. The head of the Rabbanut in Israel and the head of the Bet Din of Jerusalem.

As mentioned above, many of the approbations contain comments on Pardes Yosef, and R. Kook’s is one of these. R. Kook, in attempting to answer a question raised in the work, records an interesting story regarding R. Yehoshua Leib Diskin. R. Kook explains that R. Diskin remained lucid, with all his mental faculties, right up until his death. As proof, R. Kook tells the story of a woman who brought a cloth which had a stain to determine a niddah issue. R. Diskin ruled strictly. The woman was unhappy with the ruling and assumed R. Diskin only ruled that way because he couldn’t really see or understand the issue. So, without telling R. Diskin brought it back to him, but didn’t tell him it was the same as before. R. Diskin looked at it and immediately identified it as the very same cloth and issue as before. Those around him were astounded, how could he possibly know that this nondescript cloth was the same? To which R. Diskin responded that it has such-and-such number of threads. The students then took the cloth apart and sure enough it had exactly the thread-count R. Diskin said.[8]

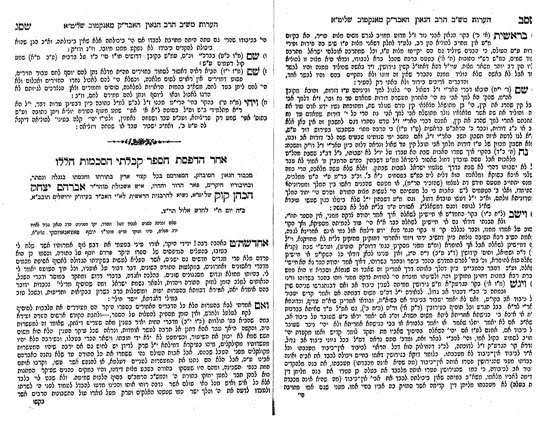

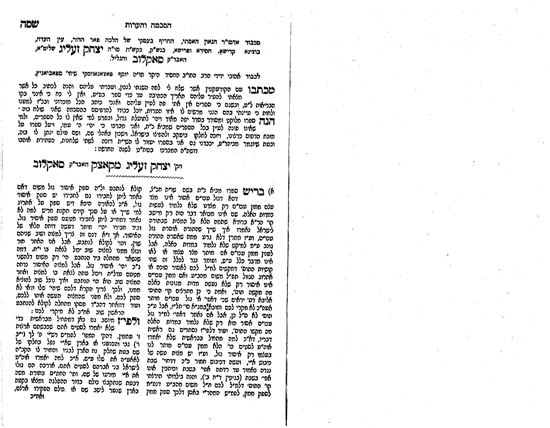

The Pardes Yosef was and is a fairly popular work and as such has been reprinted multiple times. Indeed, since its publication in 1931, it was published an additional three times in photo-mechanical reproductions. In some of these reproductions, however, R. Kook’s approbation is missing. Instead, there is a blank page where his approbation previously appeared.

Uncensored:

Censored:

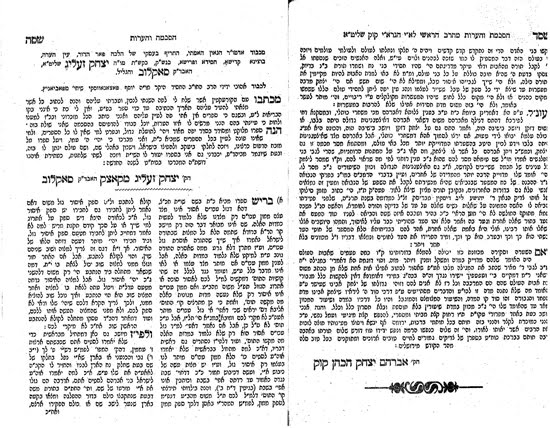

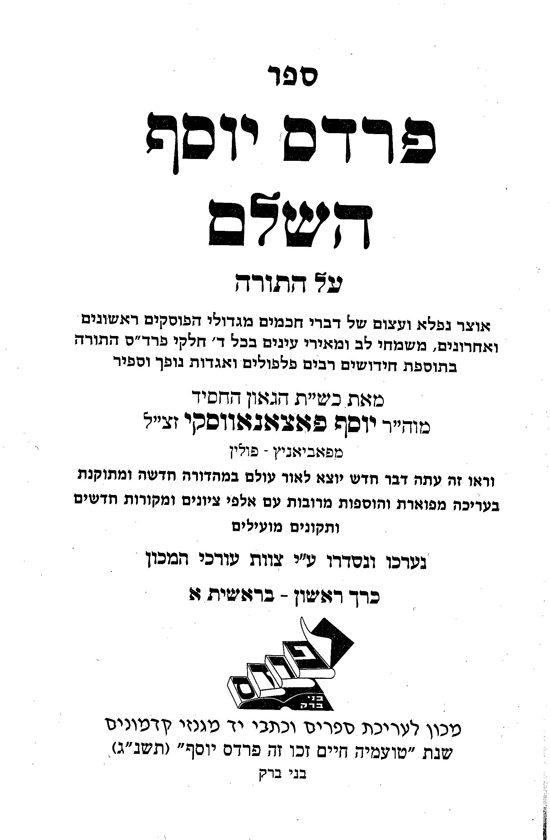

The Pardes Yosef while popular was a difficult work. In part this is due to the overuse of obscure abbreviations.[9] In 1995, a new edition of Pardes Yosef was published, and this edition attempted to make the book more user-friendly by removing the abbreviations, resetting the type and other improvements. This edition was published in Benei Berak, and notably includes R. Kook’s approbation in reset type. But, for this edition, only part of the first volume was published and then no more.

In 1998, a new edition, boasting many of the improvements contained in the 1995 edition began being published again in Benei Berak. Although titled Pardes Yosef ha-Shalem (emphasis added), this edition is incomplete at least regarding R. Kook’s approbation. That approbation is again missing.

Today, Hebrewbooks includes the first edition – the edition that includes R. Kook’s approbation (

link). While presumably unintended, Hebrewbooks has followed R. Pazanavski’s wish that his work bear the approbation of R. Kook.

[1] In reality there are many more databases which either include Hebrew books or are devoted to Hebrew books. Generally, these are found on various library’s websites and are limited to the works that the particular library owns and are not intended to be comprehensive. The three databases discussed above intend to include all Hebrew books.

[2] A partial list of Hebrew books which appeared, but were removed from Hebrewbooks.org is:

- Arnold Ehrlich – Mikra Kifshuta (Berlin 1899)

- R. Gedaliah Nadel – Betorato shel R. Gedaliah (see Rabbi Natan Slifkin on that here)

- Moses Mendelssohn – Phaedon (Hebrew)

- Moses Mendelssohn – Netivot Shalom – Bamidbar (Vienna 1846) (40004)

- Moses Mendelssohn – Netivot Shalom – Devarim (Vienna 1846) (40005)

- R. Yom Tov Schwartz – Maaneh Leigrot (which is available elsewhere online here)

- Joseph Perl – Megaleh Temirin 1819 (43110)

- A Karaite siddur from 1737 (43124)

- Naftali Herz Wessely – Olelot Naftali – Bereshit 1842 (34363)

- Naftali Herz Wessely Wessely – Shirei Tiferet 1809 (43205)

The numbers are provided in some cases, where available, showing where they used to be on Hebrewbooks.org. Needless to say, many books remain which would be removed, if the criteria applied to these were able to apply to the many needles in a nearly 50,000 piece-strong haystack.

Here is a graphic depicting how one of these books was on Hebrewbooks.org. It is no longer.

Note that this very book bears approbations from Chacham Isaac Bernays and R. Jacob Ettlinger. For more on Wessely in seforim, see Eliezer Brodt’s post

here.

The Otzar Ha-hochma removes books as well, even from it’s standard “non-Benei Torah” version. For example, the periodical Yerushalayim (Zolkiew 1844) was there. Now it is gone.

[3]For other examples of using modern technology and modern methods to promote a traditional (albeit anachronistic) point-of-view, see Yoel Finkelman, Strictly Kosher Reading: Popular Literature and the Condition of Contemporary Orthodoxy, Academic Studies Press: 2011.

[4] For examples of censorship regarding R. Kook see Dr. Meir Raflad “’al Peletat Soforim” Sinai 122 (1998) 229–232; Dr. Meir Raflad “Oy l’Tzadik v’Oy l’Shcheno” Hatzofeh, Sept. 2, 2005.

[5] See, e.g., Gershom Gorenberg, The Unmaking of Israel, HarperCollins Pub., 2011, arguing that the modern-day Israeli settlements and their attendant issues springs from R. Kook’s philosophy.

[6] The title page records the date of publication as the Hebrew year of 5690, (printed in the year “Kechu Sefer Pardes Yosef ha-Zeh”) in reality it wasn’t completed until 5691, as R. Pazanavski signs the final page 13 Tishrei 5691. Ultimately, only three volumes would be published, Berashit, Shemot and Va’yikrah. While R. Pazanavski wrote on all five volumes of the Torah, the remaining manuscript was lost during the Holocaust. The Mandelbaum edition, discussed below, “completes” the remaining volumes in the same style as the first three. Thus, today, Pardes Yosef is available on the entire Torah.

[7] In light of R. Pazanavski’s affilation with Gur and specifically, the then current rebbi, Penei Menachem, it’s unsurprising that R. Pazanavski viewed R. Kook positively. It is well-known that the Penei Menachem had a favorable view of R. Kook. See R. Eliezer Sirkes, Ish ha-Emunah, Yitzhak Alfasi ed., Tel Aviv: 1979, pp. 111, 124, 128, 131. One of the putative goals of the Penei Menachem when he went to Israel was to attempt to reconcile R. Kook and R. Sonnenfeld. Thus, it is especially ironic that, as discussed below, the Mandelbaum edition removes R. Kook’s approbation as Mandelbaum is a Gur hassid.

[8] This story appears to have been related at one of the eulogies after R. Diskin’s death. See Yeshah Orenstein, Ma’amar Shelamut ha-Mitzeyot, in Hiddushei R. Yeshayah Orenstein, Jerusalem: 1972, p. 185. A similar story is told about R. Eliyahu Mizrachi (1450-1526). See R. Abraham Kalphon, Ma’aseh Tzaddim, Assaf Revivi ed., Ashkelon: 2009, p. 160. According to this story the king (presumably it would be the Sultan and not a king as after 1453, Constantinople was ruled by the Ottomans and its leader was a sultan) wanted to show the greatness of R. Mizrachi. To do so, he took a special chair and placed R. Mizrachi upon it and asked him to calculate the distance between him and the sky. R. Mizrachi asked for a pen and paper and, after some calculations, wrote down a number which the king took as proof. Of course, this wasn’t convincing to those around. But what the king then did was some time later the king took out the chair again but this time he ordered a small coin be placed under the chair’s legs, unbeknownst to anyone else. He then had R. Mizrachi come back and the king feigned that he couldn’t recall R. Mizrachi’s prior calculation and asked him to repeat it. This time R. Mizrachi wrote down the same number but said that is now seems that it needs to be reduced by the width of a coin. Like the story with R. Diskin, this demonstrated R. Mizrachi’s amazing estimation ability. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, there are no recorded stories of any famous rabbi winning guess the number of jelly beans in a jar contest.

[9] On the use of obscure abbreviations see Ya’akov Shmuel Speigel, “Ha-Shimush be-Kitzurim ve-Roshei Tevot Shanom Shichim,” Yeshurun 10: 2002, pp. 814-30.

5 thoughts on “The censorship of Rav Kook and other Hebrew books on Hebrew book databases”

swartz's book deserves to be taken off the list,why dont you read the introduction its insane!i enjoyed your article however you cant make sweeping generalzations regarding censorship

swartz's book deserves to be taken off the list,why dont you read the introduction its insane!i enjoyed your article however you cant make sweeping generalzations regarding censorship

99% of readers have no idea if a sefer has questionable material in it,thus this article is academic at best. you left out the classic my uncle the netziv which is no longer available

Someone more knowledgable than me shared with me the following when I sent him this blog:

The writer doesn’t know that the Penai Menachem was a toddler in 1930. The Gerrer Rebbe was the Imrei Emes. The R’ Menachem Mendel in question was probably the the Gerrer Rebbe’s brother, Rav Mendel of Povenitz (spelling probably wrong).

A few comments:

1. I know for a fact that were Mosad Harav Kook to give HebrewBooks permission, they would put up their seforim. You might want to ask MOsad Harav Kook directly about this matter rather than make the claim you did.

2. Footnote 7 refers to the Pnei Menachem in error. It is clear the reference meant to mention the Imrei Emes who was the Pnei Menachem's father.

3. Also in Footnote 7 – it seems as though the fault for the omission of Harav Kook's haskama is with Mandelbaum. Have you asked for his response to this? Was it him or perhaps the publisher's? I would attempt to find out.