New Writings from R. Kook and Assorted Comments, part 3

Marc B. Shapiro

In truth, Aviezer’s understanding is not unique to him but is shared by many. They all assume that if Aristotelian eternity was proven, Maimonides would then reinterpret the Torah in accordance with this, for he says that he is indeed able to do so. This viewpoint is held by some of the top Maimonides scholars alive today. From greats of previous years who hold this position, I can add R. Elijah Benamozegh:[4]

Even Pope John Paul II adapted this saying, in a passage that looks like it could have been written by R. Hirsch,[8] R. Kook, or R Natan Slifkin:

The Bible itself speaks to us of the origin of the universe and its make-up, not in order to provide us with a scientific treatise, but in order to state the correct relationships of man with God and with the universe. Sacred scripture wishes simply to declare that the world was created by God, and in order to teach this truth it expresses itself in the terms of the cosmology in use at the time of the writer. The Sacred Book likewise wishes to tell men that the world was not created as the seat of the gods, as was taught by other cosmogonies and cosmologies, but was rather created for the service of man and the glory of God. Any other teaching about the origin and make-up of the universe is alien to the intentions of the Bible, which does not wish to teach how heaven was made but how one goes to heaven.[9]

Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, whose prolific writing continues to astound, has recently said the same thing: “There is a difference between science and religion. Science is about explanation. Religion is about interpretation. The Bible simply isn’t interested in how the universe came into being.”[10] R. Chaim Navon put the matter as follow[11]:

התורה אינה מתעניינת במידע מדעי, אלא בערכים רוחניים. לא כך כך אכפת לתורה מנוסחאות מדעיות; אכפת לה הרבה יותר מדרכי התנהגותו של האדם, מאורחות חייו ובעיקר מעבודתו של האדם את בוראו. משום כך, לא כל כך חשוב לדעת האם האדם היה שייך פעם לעולם החיות; מה שחשוב באמת הוא האם האדם הצליח להיחלץ משם.

In other words, the Torah has nothing to tell us when it comes to science. Therefore, there can be no such thing as a conflict between Torah and science.[12] With such an approach, all of the reconciliations between science and the Book of Genesis (e.g., a “day” is really an eon, the dinosaurs are from prior worlds, etc.), which for awhile were popular in Orthodoxy, are really missing the point. The old apologetics assumed that the Torah was in accord with science, and was even teaching scientific truths. It was just that we had to read the text differently than it had been read until now. Yet as with R. Kook, from Sacks’ and Navon’s perspective the creation story is a myth, namely, a tale designed to impart cosmic truths.[13] Although this position has been argued most forcefully by Slifkin, and has found a very receptive audience at synagogues (as I can attest, having tag-teamed with Slifkin as scholars-in-residence), are there any high schools that teach the Creation story in this fashion?

Aviezer “blames” geocentrism on the Church, and yet Maimonides (and every other Jewish and Islamic thinker of his day) was a geocentrist. Maimonides also had a strong anti-anthropocentric view, as he did not regard man as the central purpose of the universe. This view of Maimonides was an important source for Norman Lamm in his famous article “The Religious Implications of Extraterrestrial Life.” [16] Only those who are convinced that they are the center of the universe would be troubled by the discovery of other inhabited worlds, and that is why Maimonides’ outlook came in so handy for Lamm.

Returning to Maimonides and creation, I want to call attention to a very interesting article by R Meir Triebitz. It appears in Reshimu, vol. 1 no. 2 (2008), the journal of the so-called Hashkafa Circle. See here.

As explained in the preface to the first volume, this “Circle” aims to fill a gap in haredi yeshiva education by focusing on the classics of medieval Jewish philosophy which are pretty much ignored in contemporary haredi society. We thus have a situation where great talmudists and halakhists ignore major themes of Jewish philosophy, which were dealt with at length by the medieval sages. When there are theological discussions in haredi literature, they invariably reflect a very conservative position, often at variance with the major rishonim. I already touched on this issue in my conclusion to The Limits of Orthodox Theology, and if Triebitz and his group are successful this situation could be reversed.

However, they won’t be successful for the simple reason that the outlook of the medieval Jewish philosophers is opposed in so many ways to haredi ideology that it will never become part of the haredi curriculum. In fact, I don’t think it is possible to be a serious student of medieval Jewish philosophy and at the same time identify with any of the regnant haredi worldviews. (You might dress the part and send your children to haredi schools, but that is not the same thing as identifying with a worldview.) This is so for many reasons, primary of which is that medieval Jewish philosophy is about the search for truth. The papal model of haredi society, where the quest for truth is subordinated to the dictates of the religious authority figure, is diametrically opposed to what our great medieval philosophers taught.

Until now, three issues of Reshimu have been published, all available on its website, and it is refreshing to see haredi writers grappling with important philosophical problems. While in many cases the writers are unaware of basic academic studies in these areas, and the journals could be edited in a better fashion (eliminating typos and stylistic problems), there is a great deal to learn from some of the essays. This is especially the case for Rabbi Triebitz, who because of his wide-ranging knowledge and keen insight deserves to be better known. I encourage all to read his articles and those who have time can also watch numerous videos of his shiurim here.

In his article referred to above, Triebitz offers a commentary on Guide 2:13, where Maimonides discusses the various views of creation. It is a very challenging essay which, unless I have overlooked an academic article, presents a new perspective, not an easy task in Maimonidean scholarship. In this essay Triebitz takes his place with the esoteric readers of Maimonides. He concludes that Maimonides does not really believe in creation ex nihilo, since for Maimonides this is a mental concept, not a scientific fact. From a scientific perspective, Maimonides adopts Aristotle’s view of the eternity of the world, but this is not something that could be communicated to the non-sophisticated reader. However, those who grasp what Maimonides is saying will realize that “Creation ex nihilo is not a contending theory of creation . . . but rather a product of man’s thought which introduces a dimension other than the objective physical world pictured by Aristotelian physics.” (p. 145)

Needless to say, this approach of Triebitz also turns Maimonides’ fourth principle, which insists on creation ex nihilo (including the creation of time), into a “necessary belief.” Here is another selection from the essay:

Rambam is therefore intimating that in order to posit God’s complete incorporeality it is necessary to extend the physical world ad infinitum. Since physical infinity is impossible, it is time which must be infinite. Monotheism demands eternity. Law and ethics, however, are based upon Divine free will and Divine free will in turn demands creation ex nihilo. Since creation ex nihilo, as Rambam has already pointed out, cannot have taken place at any time, it cannot be a theory of creation. The antinomy between eternity theories, particularly Aristotle’s, and the irreducible creation ex nihilo is in fact no other than the dichotomy between ontology and ethics (p. 161).

Triebitz returns to Maimonides and creation in Reshimu vol. 1 no. 3 (2009) and once again explains that in his opinion Maimonides doesn’t really believe in creation ex nihilo.

I now want to return to the Creation story, and how some have argued that it should not be taken literally. I dealt with this in my previous posts and received some e-mails by people referring to other sources that say so, including R. Gedaliah Nadel. I am grateful for all the e-mails, but the reason I didn’t mention these sources, including R. Nadel, is because all of these sources are well known. Since I was not trying to write a comprehensive study of approaches to creation, I didn’t see any need to cite them. In general, my posts here are not like my articles or books, in that I am trying to call attention to interesting ideas and texts, rather than producing complete studies of any topic.

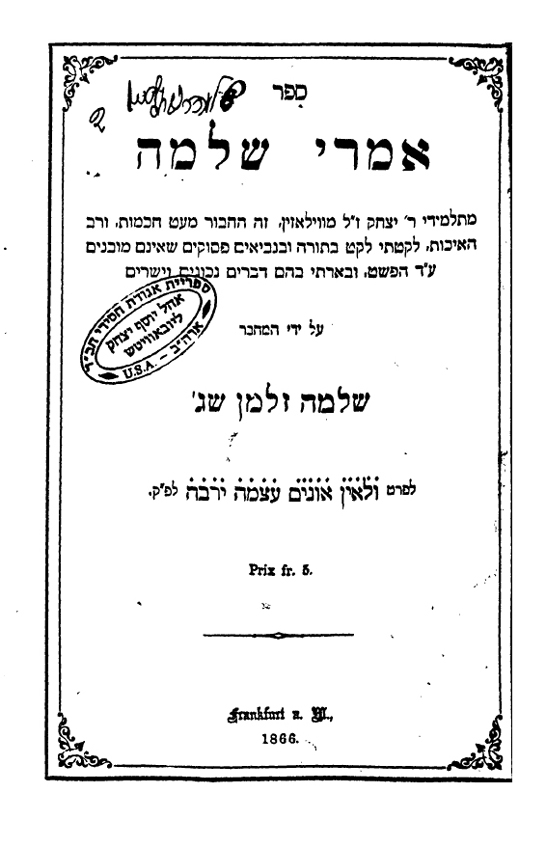

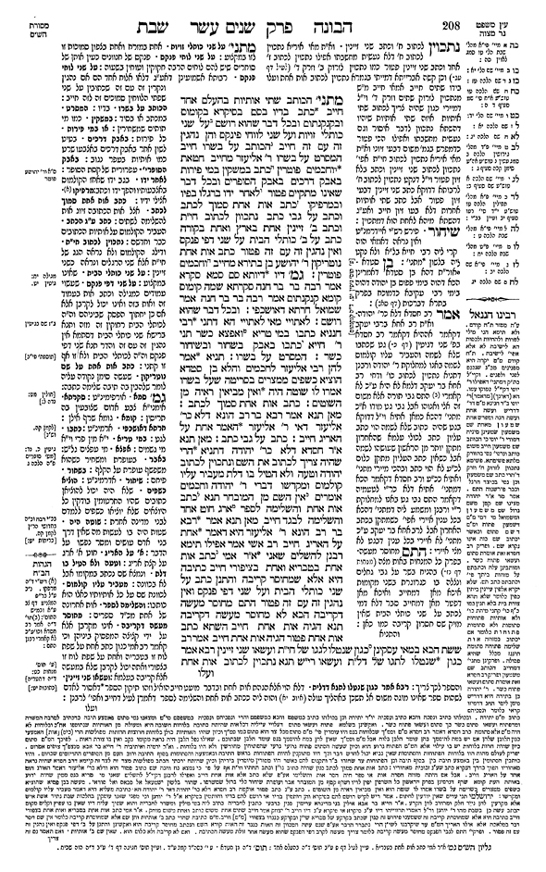

Yet since people are obviously interested in this topic, and took the time to send me the sources, let me thank you by citing a source that has never been referred to in all of the discussions of creation and biblical literalism. It is R. Shlomo Zalman Shag’s Imrei Shlomo, published in Frankfurt in 1866. (I have transliterated his last name as “Shag”, since that is how the Harvard catalog has it.) Here is the title page, where you can see that he identifies himself as a student of R. Isaac of Volozhin.

On p. 5 Shag refers to the trees in the Garden of Eden and the snake and says that it is obvious that none of this can be taken literally:

On page 10 he explains how the snake represents the evil inclination, an identification pretty standard among the medievals, and he beautifully explains the connection between the two:

והנחש הוא היצר הרע והתאוה . . . היצה”ר נמשל לנחש מה הנחש כשהולך להזיק אינו ברעש ובהלה רק זוחל על הארץ בלחש ומזיק כן הוא היצר הוא בא לאדם בעצה ותחבולה ומראה עצמו כאוהב עד שיפתה, ואח”כ רובץ על צווארי בני אדם כנחש הסובב על הדבר מכל צדדיו.

On p. 21 he even understands the Tower of Babel in non-literal fashion:

ונאמר לראות את העיר ואת המגדל. את העיר זו יושבי העיר כמו העיר ננוה, העיר שושן, הכונה הוא על יושביה, והמגדל הוא המעשים שעשו, נגד רצון השי”ת, כי הם היו מתגאים לעשות להם שם בארץ. והשי”ת שונא גאים ומשפיל אותם, לכן ויפץ ה’ אותם משם על פני כל הארץ.

והמגדל הוא הפורח באויר אשר ראו בשמים

At least this is how Tziyoni is usually understood. Yet it is possible that it is not to be taken literally, and I found a post that says precisely this. See here.

Pre-modern man had many stories of those who were able to rise above the ground, either by flying or being transported by God. We find this in Jewish literature as well. See, for example, Bereishit Rabbah 44:8 which focuses on the words in Gen. 15:5 ויוצא אותו החוצה. What does it mean that God brought Abraham outside? The Midrash first quotes R. Joshua in the name of R. Levi:”Did he then lead him forth outside of the world . . . It means, however, that He showed him the streets of heaven.” In response to this R. Judah b. R. Simeon said in the name of R. Johanan: “He lifted him up above the vault of heaven.” Seen in context, as a response to R. Joshua’s explanation, it seems to me that R. Judah b. R. Simeon’s statement must be understood literally. In other words, Abraham was literally transported into the Heavens. See Etz Yosef ad loc: ס”ל דהחוצה כמשמעו שהוא ממש חוץ לעולם

The most famous example of human flight in Jewish literature is that of Jesus. As described in Toledot Yeshu, Jesus was able to use God’s holy name in order to fly, and was brought down by Judas Iscariot who could also fly and defiled Jesus (which caused Jesus to lose his special powers). According to one tradition, he defiled Jesus by urinating on him, but another version has him engaging in homosexual sex while in the air, which in context certainly means rape.

וטנפו במשכב זכור . . . שטנפו במשכב זכור וכיון שטנפו ונפל הזרע על יש”ו הרשע נטמאו שניהם ונפלו לארץ שניהם כאחד

Incidentally, according to Toldot Yeshu this explains why Judas Iscariot is so hated in Christianity:

וכל חכמי הגוים יודעים סוד זה וכופרין אותו ומקללים ומחרימים יהודה אסקריוטו

See Samuel Krauss, Das Leben Jesu nach Juedischen Quellen (Berlin, 1902), pp. 48, 74.

As Morris Goldstein has noted, the second century Acts of Peter describes how Simon Magus flew over Rome, astounding all the onlookers. But Peter, through his prayer to God, was able to force Simon down, a crash landing that caused him to break his leg.[20]

Samael (Satan) can also fly, at least so we are told in the Targum to Job 28:7: סמאל דפרח היך עופא

This should not surprising as according to Isaiah 6:2 the Seraphim fly (with wings), and Hagigah 16a tells us that both angels and demons fly (also with wings).

With reference to Jesus, it is interesting to note that many Jews actually believed that he performed wonders. However, they attributed it to his knowledge of God’s holy name. Why didn’t they simply assume that all the stories about him were fiction, as modern Jews do? I think the answer is that since all of their neighbors believed the stories, and the miracles Jesus performed are said to have been done before crowds of people, many Jews therefore assumed that these tales must be historically accurate.

In general, it is a common pre-modern assumption that if a group of people, even a group from generations ago, claimed to have witnessed something, that this is a sign that it indeed took place. Today, however, we know how false this argument is. We can cite many examples of mass delusion, not to mention the fact that stories of what people in previous generations witnessed are not actually examples of many people testifying to something, but of one person, the writer, claiming as much.

The stories of Jesus that are found in Toldot Yeshu do not appear in the Talmud, but there are other stories of him found there. However, these stories place Jesus a good 150 years before he actually lived. I say this because the Talmud identifies Jesus as a student of R. Joshua ben Perahyah, who lived circa 120 BCE. In Nahmanides’ disputation, paragraphs 22, 57, he points out that the Christians are wrong on their dates. (R. Judah Halevi, Kuzari 3:65 mentions that Jesus was the student of R. Joshua ben Perahyah and says nothing about the chronological problem. The standard Hebrew edition of the Kuzari is censored [self-censored?], but the reference to Jesus can be seen in the original Arabic published in Kafih’s edition, and also in Hirschfeld’s English translation.)

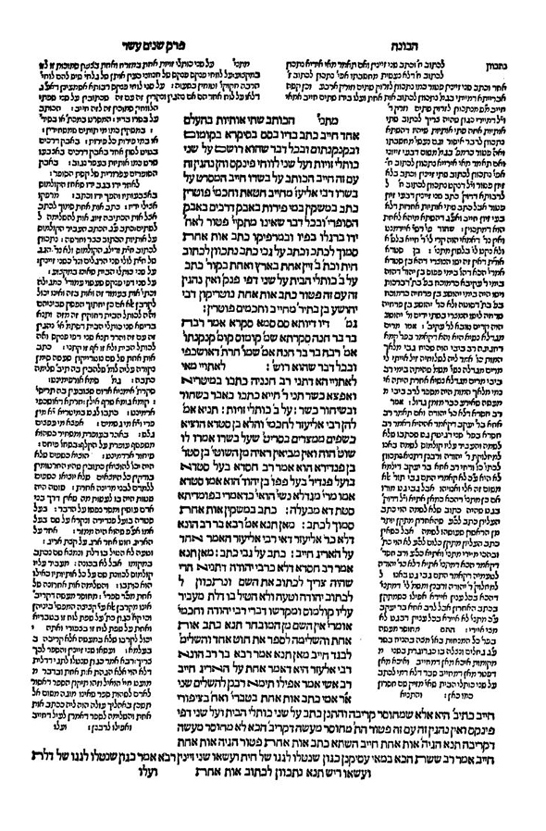

Others, such as R. Jehiel of Paris in his debate, used the chronological discrepancy to argue not that the Christians are wrong on their dates, but that the Jesus of the Talmud is not Jesus of Nazareth. I used to think that no one actually believed this, but resorted to this argument because it was a good way to deflect the Christian attacks that the Talmud defamed Jesus. However, I recently saw that Tosafot ha-Rosh, Sotah 47a, in a completely non-apologetic comment, assumes that the Talmud refers to two different men named Jesus. See also Meiri, Seder ha-Kabbalah, ed. Havlin (Jerusalem-Cleveland, 1992), pp. 69-70, and especially Havlin’s lengthy note. This was also Rabbenu Tam’s opinion, although it has been censored out of our Talmud. Take a look at Shabbat 104b, Tosafot s.v. Ben Stada in the Bomberg Venice 1520 edition, and compare to the standard Vilna edition.

Why does the Babylonian Talmud identify Jesus as a student of R. Joshua ben Perahyah if Jesus lived more than a century later? I think the answer is obvious, namely, that the Talmud had very little knowledge of who Jesus was, and thus did not know when to date him.[23] In fact, the famous story of R. Joshua ben Perahyah pushing Jesus away (Sanhedrin 107b, found in the Soncino translation) is actually a later development of an earlier story that is found in the Jerusalem Talmud. The Jerusalem Talmud’s version does not mention Jesus.[24]

Today you have people [who] are considered Orthodox and they say [that] the Gemara made a mistake in history. There are a lot of people like that. . . . This is an ongoing debate. Just seventy years ago, before the Second World War, some of the rabbanim in Europe wrote in their seforim [that] it’s a well known fact that the bayit sheni was much more than 420 years. There is 150 years missing there. . . . We are used to this already. When Rabbenu Azariah min ha-Edomim (De Rossi) came out with his sefer Meor Einayim . . . and he said that maybe the chachmei ha-Gemara were wrong in history . . . many rabbanim were so upset they wanted to make a herem against him. I think they did make a herem; I am not sure. . . . Today, everybody is used to this. We assume that the Gemara is not necessarily expert on history, The Gemara can make mistakes in history. Today it’s not assumed to be apikorsus to say [this]. . . . If Azariah De Rossi would have printed his sefer today, no one would have been so excited about it.

For a hasidic perspective on this matter, which is very much in line with modern approaches to Aggadah, see R. Shlomo of Radomsk, Niflaot ha-Tiferet Shlomo (Petrokov, 1923), nos. 73-74. R. Shlomo stresses that when the Talmud tells a story, it does not matter if the facts are contradicted by other talmudic stories, because what is important is not the story itself, which need not be historically accurate, but rather the lesson to be instilled.

ובזה יש ליישב פליאה גדולה אשר יש לשאול, מה זה שמצאנו בכל הש”ס ומדרשים מסופרים מעשיות ומופתים מתנאים ואמוראים בשינוי נוסחאות מאד, זה יאמר כן היה המעשה, וזה יאמר כן . . . דאין אנו דנין על החומר, רק על הצורה, ולפי הצורה המוכנת בענין הזה, באופן זה מספרים חז”ל את המעשה והסיפור, וממ”נ אם להלל ולשבח ולפאר את התנא, או בהיפוך לגנות הרשע, הלא הצורה מוכנת לכ”א . . . ואם להשיג מטרת ותכלית ענין הנרצה בהסיפור הזה לעורר רושם ורעיון להשומע להבין דברי תורה ולעורר אמונת השגחה וכחן וגבורתן של הצדיקים, ג”כ האיכא, ומאי איכפת לן אם החומר מונע, החומר בטל לגבי הצורה, לכן אין נ”מ בין אופן זה לנוסחא אחרת כי הכל תורת אמת.

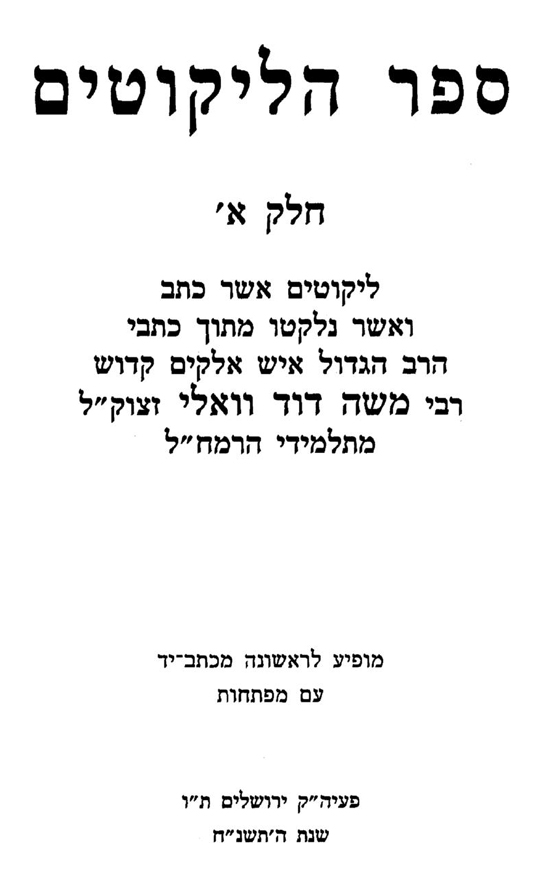

Returning to the subject of Jesus and R. Joshua ben Perahyah, I think readers might find another text interesting. It is by the kabbalist R. Moses Valle, who was an older colleague of R. Moses Hayyim Luzzatto in Padua. (Although Luzzatto was the leader of their circle, and Valle was thus subservient to him, I don’t know if it correct for the title page to describe Valle as a “student” of Ramhal. I grant that even Italian texts describe Valle as such. See R. Mordechai Samuel Ghirondi, Toledot Gedolei Yisrael [Trieste, 1853], p. 230.)

Interestingly, R. Abraham Abulafia appears to also have identified Jesus as Messiah ben Joseph. See Moshe Idel, Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah (Albany, 1988), p. 53.

To be continued.

לו ידעו הרבנים התלמודיים בפלוסופיא לא היה [!] שותקים לו בכאן

The Maharal, Netivot Olam,p. 224, writes:

והנה בנה עיקר ראייתו על התנועה הנצחית וזהו הפך האמונה שאין אנו מודים בזאת ההנחה. וא”כ כבר נפל הבנין בכללו

That the Guide is actually a theologically more conservative work than the Mishneh Torah has recently been argued by Charles Manekin, “Possible Sources of Maimonides’ Theological Conservatism in His Later Writings,” in Jay M. Harris, Maimonides After 800 Years (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 207-230. One should not forget that the Maimonidean controversy was precipitated by the Mishneh Torah, in particular Sefer ha-Mada, not the Guide.

There I wrote:

While in the popular mind myth often is identical with fairy tale, this is not how scholars understand myths. For them, myths communicate cosmic truths in non-historical story form, and they are not synonymous with legends. My dictionary explains myth as “a usually traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon.”

S. of On the Main Line called my attention to Shadal’s letter in Iggerot Shadal, p. 661, where he speaks about the religious value of “illusions,” that is, matters that are not factual, but nevertheless have great religious value. In this letter we see Shadal, the great opponent of Maimonides, nevertheless adopting his own version of “necessary truths.”

שאין הריליגיאון חביבה לא-ל בשביל אמתתה, רק בשביל תועלתה בתקון המדות, ועל כן אין צורך שיהיו כל דבריה אמתיים, ושאין לנו עכ”ז להרחיק א-להיותה, ושאין להרחיק מהא-ל הגדת דברים בלתי אמתיים כי להגיד כח מעשה בראשית לבשר ודם א”א, ולא יתכן קיום החברה והצלחת האדם בידיעת האמת, אלא באיללוזיון, כי כן הטבע (אשר הוא בלא ספק רצון הא-ל) מרמה אותנו בענינים הרבה.

[14] Rather than refer to any number of books on the history of astronomy, here is what the Wikipedia entry on “Geocentric Model” has to say:

Adherence to the geocentric model stemmed largely from several important observations. First of all, if the Earth did move, then one ought to be able to observe the shifting of the fixed stars due to stellar parallax. In short, if the earth was moving the shapes of the constellations should change considerably over the course of a year. If they did not appear to move, the stars are either much further away than the Sun and the planets than previously conceived, making their motion undetectable, or in reality they are not moving at all. Because the stars were actually much further away than Greek astronomers postulated (making movement extremely subtle), stellar parallax was not detected until the 19th century. Therefore, the Greeks chose the simpler of the two explanations. The lack of any observable parallax was considered a fatal flaw of any non-geocentric theory. Another observation used in favor of the geocentric model at the time was the apparent consistency of Venus’ luminosity, thus implying that it is usually about the same distance from Earth, which is more consistent with geocentrism than heliocentrism. In reality, that is because the loss of light caused by its phases compensates for the increase in apparent size caused by its varying distance from Earth. Once again, Aristotle’s objections of heliocentrism utilized his ideas concerning the natural tendency of earth-like objects. The natural state of heavy earth-like objects is to tend towards the center of the earth and to not move unless forced by an outside object. It was also believed by some that if the Earth rotated on its axis, the air and objects in it (such as birds or clouds) would be left behind.

באותה שעה [כשעברו את הים] ברא להם הקב”ה ארץ חדשה כמו בבריאת העולם בששת ימי בראשית.

These two sources are cited by R. Judah Leib Zlotnick, “Bereishit” bi-Melitzah ha-Ivrit (Jerusalem, 1938), p. 27.

וזה היה כונת דור הפלגה ג”כ שבקשו לקבוע מושבם בכדור ירחי ששם יהיו נצולים ממבול וחשבו לעשות ע”י ספינה הנ”ל אפס כיצד יגביהו אותו הספינה למעלה מאויר העכור ולזה חשבו לבנות מגדל גבוה כל כך עד למעלה האויר ההוא ומשם יוכלו להשתמש בספינה הנ”ל לשוט באויר עד כדור הירחי.

[20] See Goldstein, Jesus in the Jewish Tradition (New York, 1950), p. 302 n. 34.

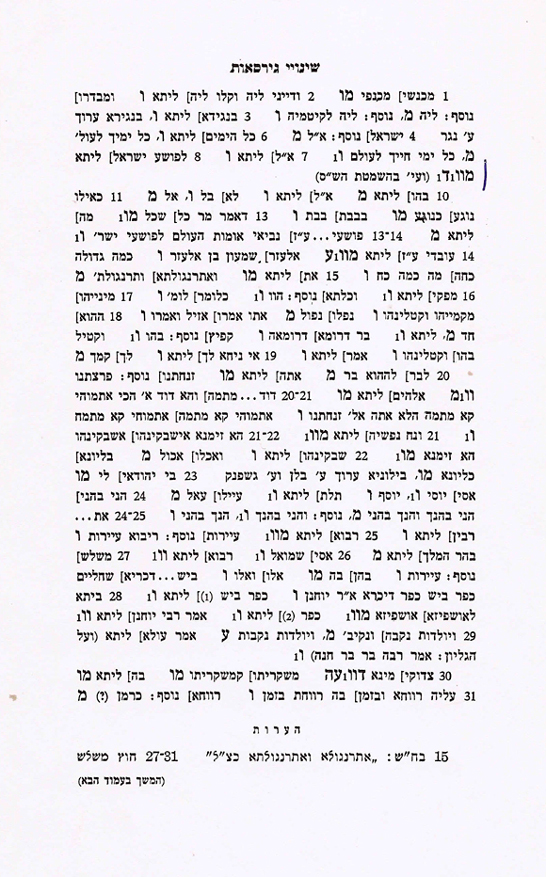

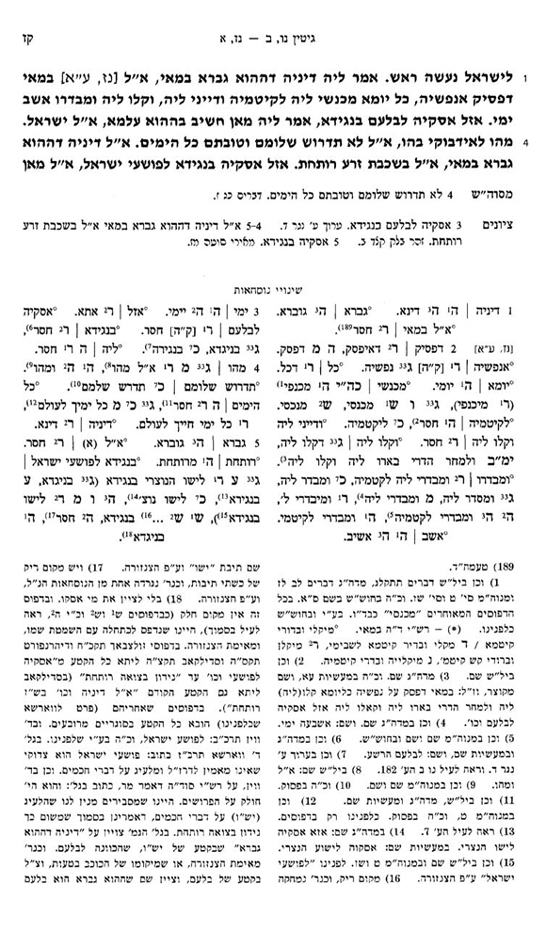

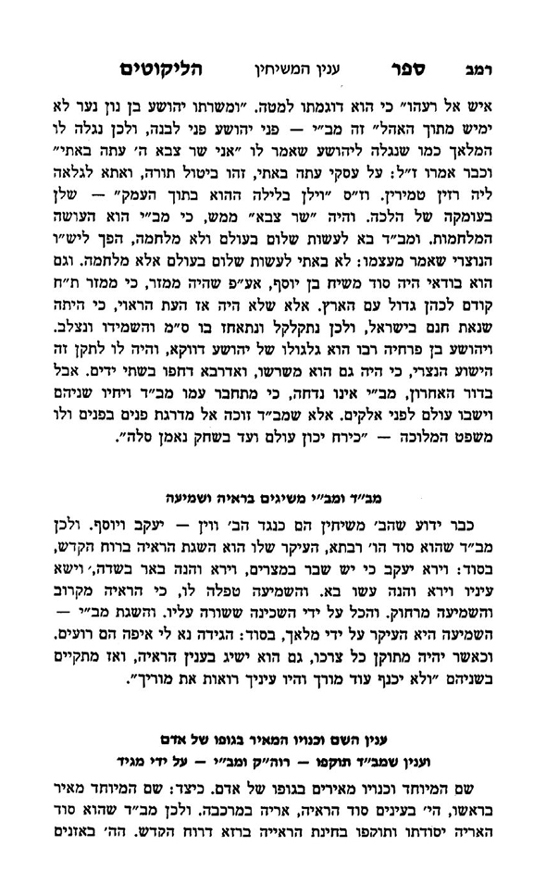

The original version of Sanhedrin, which mentions Jesus, is not found in the Artscroll edition. In other words, the Artscroll Talmud, including the Hebrew version, is still a censored, and thus defective, edition. I find this quite amazing. Is there a valid reason why Artscroll has not returned the Talmud to its pristine text? Speaking of internal censorship, here is another amazing example. Gittin 57a has a reference to Jesus, and this is preserved in the Munich manuscript and other uncensored mss. (and recorded in the Soncino translation). Here is a copy of the Munich manuscript. Look three lines above the large word אתרנגול

It states that Jesus was raised from the dead through incantations: אסקי’ לישו בנגיד’. In the standard text this has been altered to read, instead of Jesus, לפושעי ישראל. Now here is a copy of Meir S. Feldblum’s Dikdukei Soferim on Gittin. See how he wouldn’t even record what the Munich edition stated, and instead advises the reader to examine Hashmatot ha-Shas!