R. Flensberg, Donkeys, Antelopes and Frogs

R. Flensberg , Donkeys, Antelopes and Frogs

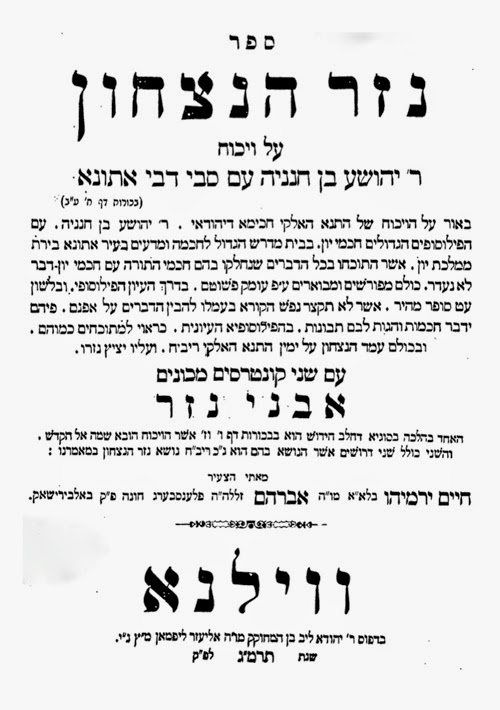

Recently, a book, Aggadata de-Ve Rav, Machon Limud Aggadah, Ashdod, 2010, pp. 50, 176, 56, collecting various works attempting to explain the difficult and, on their face, rather odd stories (aggadot) that appear in Baba Batra (73a-74) many of which involve odd animals do odd things. In addition to these passages, there is another odd passage in Bechorot (7b) which also involves an animal, a donkey also engaging in odd behavior. This passage was too was also the subject of many works attempting to explain it. This new book reprints four of the many works attempting to decipher the stories in Baba Batra, R. Elyakim Getz, Redfunei be-Tapuchim, R. Zev Wolfe Boskowitz, Le-Binyamin Amar, R. Eliyahu Guttmacher, Tzafnat Panach, and the fourth is Aggadot Soferim, which a collection of materials on the topic from Ritva, Gra, and R. Efrayim Lunschutz (author of Kli Yakar, among other works). While three editions of Redfunei be-Tapuchim are available on Hebrewbooks (here, here and here) Le-Binyamin Amar and Tzafnat Panach are not. The book also provides biographical details about these authors (56 pp.). Additionally, a list of others books devoted to the Baba Batra stories which are not reprinted herein are included. The list provides over 25 such works devoted to the stories in Baba Batra. Regarding the donkey of Bechorot there are almost as many books on that topic. We have found 23 such works. One of those discussing the donkey of Berchorot is an important, little-known and recently reprinted book on that topic. Specifically, R. Hayyim Yirmiyahu Flensberg’s Nezer ha-Nitzhon, Vilna, 1883 (reprinted Machon Mishnas Rabbi Aaron, Israel, 2001).* Amongst the many who praised Flensberg’s book, was his teacher, the Netziv. And, it was not only the Netziv, but Flensberg received a request from his alma mater, Volozhin, that his book was so popular could he please send ten additional copies. Thus, in light of this book discussing, what is arguable similar aggadot, we provide background on this little-known Lithuanian rabbi, his works and children.

Flensberg was born in 1842. And, as many great rabbis, there are both miraculous stories told of his conception and birth as well as how bright he was. Indeed, it is said that he knew 300 pages of Talmud, with Tosefot, at his bar-mitzvah. While those stories are not unusual, what is unusual was the bar-mitzvah gift he received from his rebbi, R. Ya’akov Tuvia Goldberg, a copy of Avraham Mapu‘s Ahavat Tzion, perhaps the first Hebrew novel. As his rebbi saw that Flensberg expressed an interest in studying Hebrew, his rebbi decided this book would be appropriate. Apparently, this gift was so important, that in the biography of Flensberg, written by his son Yitzhak Yeshayahu Flensberg, some seventy years later, records this. It is worth noting that, although this biography appears at the beginning of the second volume of Flensberg’s Torah commentary which was reprinted in 2000 by the Lakewood publisher, Machon Mishnas Rabbi Aaron, this fact remains in this edition.

It should also be noted that, while on its face, it is questionable how much one can read into a single bar-mitzvah gift, Shaul Stampfer views this gift as highly significant. Stampfer writes, that although the policy of the Volozhin rabbinic administration was to prohibit haskalah literature, Flensberg is used as an example to prove that “not all the students viewed reading haskalah literature as conflicting with torah study.” Shaul Stampfer, The Lithuanian Yeshiva, Jerusalem, 2005, 171. Stampfer cites the story of the bar-mitzvah gift and notes that although Flensberg received this gift “he still went to study in Volozhin.” Id. at 172. Indeed, it is even more questionable to use the bar-mitzvah gift to understand the Volozhin students’ views on haskalah literature when one considers the timing. Flensberg didn’t go to Volozhin immediately after his bar-mitzvah, rather it would be over a year and a half before he went to Volozhin. [1] During that time, Flensberg stopped studying with R. Goldberg, the bar-mitzvah gift, giver and began studying with R. Leib Charif (eventual Chief-Rabbi of Tytvenai and Rietavas Lithuania). (Also relevant for our purposes is that R. Leib authored a book on the donkey Gemara in

Bechorot called Eizot Yehoshua.) Thus, there are two significant factors that may sever any ties between Flensberg’s bar-mitzvah gift and his ultimate decision to go to Volozhin.

In all events, Flensberg thrived at Volozhin. He studied in the Netziv’s group and was close to the Netziv. Additionally, he was selected for the highly prestigious position at the Volozhin Yeshiva as the Purim Rav of Volozhin. His appointment to this position took place sometime before he left Volozhin in 1859, making this the earliest, and perhaps one of the only, recorded mention of this custom from Volozhin.[2] In fact, there are those who doubt the existence of the custom of Purim Rav at Volozhin.[3] This appears to undermine that position. Additionally, the description of the Purim Rav position is of interest. According to Flensberg, the position was fairly innocuous. For the two days of Purim, the Netziv would cede his position to the best student. The student would wear the Netziv’s hat and use the Netziv’s walking stick. All the students would give the Purim Rav great deference. They would also pepper him with questions both about Purim and more comical questions. The Purim Rav would answer in the Purim spirit. Nowhere is there any mention of lack of respect or, seemingly anything that is objectionable.

After leaving Volozhin, he married Itta, whose father was R. Mendel Katz, who would eventually become a rabbi in Radin. After his marriage he went to study in a bet midrash in Kovno. Although some refer to this place as “the Kovno Kollel,” it cannot be referring to the famous Kovno Kollel as that did not begin until 1877 long after R. Flensberg left Kovno and entered the rabbinate. During his time in Kovno Flensberg became friendly with R. Yitzhak Elchonon Spektor. After leaving Kovno in 1869 to his first rabbinic position, and, in 1889, after a few other employment changes, Flensberg ended up in Shaki as the chief rabbi.

Flensberg found the rabbinate a good fit and focused on derash and philosophy. But, before publishing any of his books, he penned a number of important articles in various newspapers including Ha-Levonon, Ha-Melitz, and Ha-Maggid. In general, he took a rather novel views towards newspapers. At the time, many viewed newspapers as a threat to Orthodox Judaism as it exposed people to different views that they otherwise wouldn’t be exposed to. Thus, many took the position that reading a newspaper was prohibited. Flensberg, however, recognized that merely ignoring the problem is ineffective. Instead, he proposed that the Orthodox start their own newspaper so that their views will be available to all. This view echos that of R. Yaakov Ettlinger, who started the Orthodox journal Shomer Tzion ha-Ne’eman. (And, it appears, the same debate is happening, again, today with regard to the internet and related technologies.) In addition, Flensberg also penned a series titled Moreh Neukei ha-Zeman he-Hadash, which some view an indirect attack against Nachman Krochmal‘s similarly titled work. Flensberg wrote this essay during a time that he was suffering from headache and prohibited from Torah study. Thus, turned his focused to producing essays for newspapers.

After his wife died in 1882, he published his first work, Nezer ha-Nitzhon. As mentioned above, this book contains a lengthy explanation of the talmudic story regarding the famous donkey. Additionally, he includes two derashot at the end. In the introduction, he credits his wife for the publication and explains that this book is in her memory. In 1897, he published his next books, She’alot Hayyim, Divrei Yirmiyahu in Vilna. The first titled portion is comprised of responsa and the second titled portion is comprised of dershot. The second part also contains a lengthy introduction regarding Flensberg’s view on derush, and a eulogy for R. Yitzhak Elchonon Spektor and the Godol of Minsk.

It appears that not everyone, including those who normally are very well-read, were familiar with R. Flensberg’s works. Katzman explains that R. Zevin, in Ishim ve-Shetot (p. 71), confuses R. Hayyim Flensberg with another R. Hayyim – R. Hayyim Soloveitchik. The statement R. Zevin attributes to a child R. Hayyim Soloveitchik, and which R. Zevin himself doubts it comports with what we know about R. Hayyim Soloveitchik’s manner of deciding law, actually appears in R. Hayyim Flensberg’s She’alot Hayyim, no. 14.[4]

In 1905,[5] he published his commentary on Hasdai Cerscas’ Ohr Adonay.[6] This is one of the very few commentaries on this very difficult work. Flensberg prefaces the book with an in-depth introduction regarding the work and its author. R. Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg wrote a glowing review of the book. Weinberg expressed surprise that no one else, with one exception, had seen fit to review such a worthy book. Weinberg notes that to write such a commentary requires not only “an ish ma’adai” but also one must be a “rav ve-goan talmudi.”[7] Flensberg includes a few pages of comments on Moreh Nevukim at the end of the book, and there are two letters one from Abraham Harkavey and the other from R. Dr. Abraham Berliner, at times, taking issue with some of Flensberg’s conclusions. This was intended to be the first part of two of Flensberg’s commentary on Crescas. According to Flensberg’s son, in 1909 the second portion was published but languished at the printer. And, after World War I broke out in 1914, the Flensberg’s were under the impression all the copies were lost. In 1925, they learned that Ester Rubinstein, Flensberg’s daughter, had saved the plates as well as other manuscripts. It is unclear if the second portion was ever actually reprinted. The JNUL appears to only have a few leaves from the second volume.

In 1910, Flensberg published his commentary on Shir ha-Shirim, Merkevot Ami. And, that same year, he also published his first volume of commentary on the Torah, Divrei Yirmiyahu, covering Genesis.

In 1914, Flensberg died, his full epitaph is included in his son’s biography which appeared in the second volume of Flensberg’s Torah commentary which was published posthumously in 1927. This version of the epitaph is the only complete one as the one on his headstone accidentally left out a line “for some [unnamed] reason.”

He was survived by his son, Yitzhak Yishayahu, and his daughter, [Haaya] Ester Rubinstein. Yitzhak Yishayhu lived in Pilwishki the town where R. Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg served as Rabbi. When Weinberg describes the learned people in Pilwishki, one of the ones he singles out is Yitzhak Yishayahu.[8] Flensberg’s daughter, however, was more well-known than his son. She married Yitzhak Rubinstein, who subsequently became Chief Rabbi of Vilna – the first in over 200 years – and she was heavily involved in Vilna community affairs and was an ardent Zionist. This is in contrast to her father who compared Zionists to “the Berlin group . . . of maskilim.”[9] She was also very learned and R. Weinberg provides that when her father couldn’t remember a source, he would ask Ester who could always provide it.

Ester was also involved in woman’s issues. She started a girls school in Vilna and wrote why woman’s suffrage is allowed under Jewish law.[10]

Ester died young, at age 43, in 1924. A Sefer Zikhron was published in her honor and, among others, R. Weinberg wrote a beautiful article describing Ester in the most honorific terms. An English translation was published by Dr. Leiman. Additionally, a memorial service was held in the Great Synagogue of Vilna, according to Leiman, “this was the only woman ever accorded this honor.”

Yitzhak, after Ester died, was involved in a bitter fight for the Vilna rabbinate that pitted him against R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzenski, and the Mizrachi versus the Agudah. In the end, Rubinstein was elected by a majority of the vote. This was viewed as untenable, and the chief rabbi position was split between the halakhic and administrative, giving both Rubinstein and Grodzenski positions.[11] This controversy was memorialized by Chaim Grade in his Rabbis and Wives, where he “resurrects” the dead Ester and imagines her as the driving force in her husband’s push for the Rabbinate. This part is untrue. However, Grade’s story of how Rubinstein was almost shouted down during his first speech (and his supporters forcibly ejected the shouters) after his election is true.

Two Broadsides Attacking Rubinstein and Urging Voters to Pick Number 18, R. Hayyim Ozer’s Number

These may have been penned by the Hazon Ish as he was heavily involved in the campaign to elect Grodzenski.

From a private collection.

Yitzhak would leave Europe to the United States to teach in Yeshiva University in 1941. On May 23, 1944, the day Belkin is inaugurated president of Yeshiva University, Rubinstein received an honorary doctorate of divinity from Yeshiva University. See also, N.Y. Times, May 23, 1944 p. 21. Rubinstein died on Oct. 30, 1945 [23 Marchesvan 5706] and is buried in Mt. Carmel cemetery in Queens.

In conclusion, R. Flensberg’s books from the one, Nezer ha-Nizhon, on the odd donkey passage to his more run of the mill responsa to his philosophy and derush are all of interest. Additionally, his children were no slouches either.

Notes

[1] Katzman asserts that Flensberg didn’t go to Volozhin until he was 16 or 17, which makes any connection between a bar-mitzvah gift and Flensberg’s entrance into Volozhin even more tenuous. See Eliezer Katzman, “A Biography of the Rav from Shaki – The Goan Rabbi Hayyim Yirmiyahu Flensberg ZT”L,” in Hayyim Yirmiayahu Flensberg, She’elot Haayim, Machon Mishnas Rabbi Aaron, Israel, 2001, 1. Katzman, however, provides no citation in support of his dates. We rely upon Flensberg’s son’s biography for our chronology. See Yitzhak Flensberg, “In Place of an Introduction,” in Hayyim Yirmiyahu Flensberg, Divrei Yermiyahu al ha-Torah, Vilna, 1927, vol. 2, V-VI.

[2] This has been noted by Katzman, “Biography” p. 2 n.2. It is odd that in Stampfer’s discussion of the Purim Rav in Volozhin, he fails to note Flensberg’s importance in establishing the existence of this custom even though the source is the same biography that contains the bar-mitzvah gift story. Cf. The Lithuanian Yeshiva at 165-68. Indeed, it is on the very next page after the bar-mitzvah gift. See “In Place of an Introduction” at VI.

[3] See this excellent article by Yehoshua Mondshein which demonstrates that the most well-known story regarding the institution of Purim Rav is likely more legend than fact. Additionally, Mondshein collects those who doubt the existence of the Purim Rav custom. But see Stampfer, at 168 where he provides that the Purim Rav custom was abolished at Volozhin because of the Netziv’s second marriage after his first wife died. At the time of the marriage the Netziv was in his sixties, and his new wife was in her twenties.

(The exact age difference is unclear, Stampfer’s source, Meir Berlin, Rabban shel Yisrael, pp. 124-31 states that the Netziv was 50 and that there was “only” a thirty year age difference and not forty.) She was a divorcee who had divorced her first husband because she felt he wasn’t a world class “lamdan.” And, she was extremely protective of her husband’s honor. It appears that she or the Netziv or both became the butt of jokes and she insisted that the Purim Rav custom end. Based upon her insistence, the custom died. For additional sources regarding the Purim Rav, see Mondshein’s article cited above and Eliezer’s post in note 23. See also R. Nosson Kamenetsky, Making of a Godol, Jerusalem, 2002, vol. 2, p. 1062 regarding Netziv and Purim Rav.

[4] See Katzman, “Biography” at 3 regarding Flensberg’s plea for an Orthodox newspaper and id. at 5 regarding R. Zevin. Regarding R. Ettlinger’s journal see Judith Bleich, Jacob Ettlinger his Life & Works, unpublished doctoral dissertation, NYU, 1974, 291-321.

[5] It should be noted that there is some confusion regarding the publication date. According to the title page that appears on the soft outer cover, the book was published in Elul 5,667 [Sept./Oct. 1906], according to the two virtually similar title pages that follow the soft cover, the book was published in 5665 [1904/1905]. In Weinberg’s review, he first refers to a 1901 publishing date which appears to be a typographical error and then, later, mentions that he was writing his review over four years after Flensberg’s commentary was published. Weinberg’s review was written in 1912 and if he was being exact, that would give it a publication date of 1908. We have used the 1905 date as it is the date given by Flensberg’s son in his biography. It is clear, that whichever year it was published, Flensberg’s commentary was not composed that year as Flensberg had been working on this commentary for some twenty years. See “In Place of an Introduction” at VII-VIII.

[6] Regarding the propriety of using of god’s name in titles see R. Hezkiyah Medini, Be’ari ba-Sadeh in his Sedei Hemed. Medeni was forced to defend the title of his magnum opus, Sedei Hemed, even though he didn’t use god’s name, only a word, that in this context refers to god only if read incorrectly. See also Ya’akov Shmuel Spegiel, Amudim be-Toldot Sefer ha-Ivri: Ketivah ve-Hatakah, Bar Ilan Univ. Ramat Gan, 2007, pp. 608-10; R. Moshe Hagiz, Halachot Ketanot, Jerusalem, 1981, no. 314 (sedi).

[7] The review originally appeared in Ha-Ivri, Jan. 26, 1912, p. 47 and is reprinted in Collected Writings of Rabbi Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg, Marc B. Shapiro, ed., vol. II, Scranton, 2003, 115-18.

[8] See Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg, “Introduction,” in R. Abraham Abba Resnick, Keli She’aret, Netanya, 1957 reprinted in Shapiro, Collected Writings, vol. II, pp. 388-402. For an overview of Weinberg’s time in Pilwishki see Marc B. Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World & Modern Orthodoxy, Littman Library, 1999, 18-50.

[9] Kaztman, “Biography” at 3.

[10] See Leiman, n. 4.

[11] See Gershon Bacon, “Rubinstein vs. Grodzinski: The Dispute Over the Vilnius Rabbinate and the Religious Realignment of Vilnius Jewry. 1928-1932,” in The Goan of Vilnius and the Annals of Jewish Culture, Izraelis Lempertas, ed., Vilnius Univ., 1998, 295-304; see also the end of Menachem’s very comprehensive post, for additional sources regarding the election.

*

In 2001, Machon Mishnas Rabbi Aaron republished all of R. Flensberg’s works with the exception of R. Flensberg’s commentary on Crescas.