Birkat Ha-Hammah in the Old Jewish Cemetary of Frankfurt

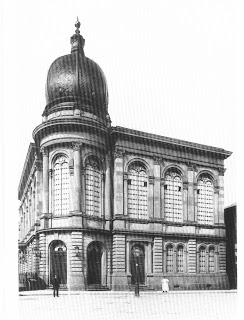

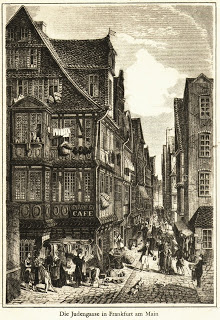

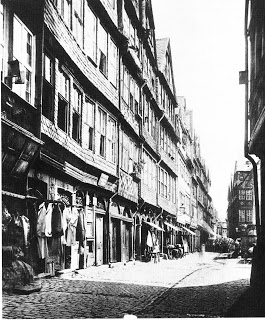

(Fig. 1) Briefly, when R. Samson Raphael Hirsch succeeded in creating a thriving separatist Orthodox Jewish community in Frankfurt in the 19th century (after the majority of the official Jewish community had joined the Reform movement), it became apparent to the official Jewish community that the best way to counter Hirsch’s success was by finding a place for Orthodoxy within the official Jewish community. The communal authorities agreed in 1878 to appoint an Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Markus Horovitz (author of שו”ת מטה לוי), aside from the Reform rabbis already in their employ. As a precondition to his appointment, Rabbi Horovitz demanded that a new Orthodox synagogue be built for his community in Frankfurt. It was constructed in 1882 – a magnificent structure – and was known as the Börneplatz Synagogue (figure 1) until its destruction by the Nazis on November 10, 1938.[15] Indeed, it was built adjacent to the Jewish cemetery, and its windows overlooked the tombstones in the cemetery. It displaced the old Jewish hospital, not a synagogue. No other synagogue in the history of Frankfurt was built overlooking the Jewish cemetery. This, then, was the synagogue that R. Tamar saw in 1921. But, of course, it didn’t exist in 1617 and therefore cannot be used to explain the accounts of R. Joseph Yuzpa Hahn and R. Asher b. Eliezer Ha-Levi.[16] Tamar’s confused account misled at least two of the recent halakhic anthologies on birkat ha-hammah, R. Gavriel Zinner, נטעי גבריאל: קידוש החמה וברכתה (Jerusalem, 2009)[17] and R. Yonah Buxbaum, קידוש החמה (Jerusalem, 2009).[18] Both cite Tamar’s account as authoritative, without further comment. In the case of R. Buxbaum (prior to his citation of Tamar), two reasons are suggested for the recitation of birkat ha-hammah adjacent to the Jewish cemetery: it provided greater space for the entire Jewish community to gather and recite the blessing together, and it provided a better view of the sun. At last, a breath of fresh air! We shall devote the remainder of this essay to an analysis of these two suggestions, to see whether or not they are likely explanations of what happened in Frankfurt. An organized Jewish community existed in Frankfurt from as early as 1150. Christian persecution of the Jews in Frankfurt was rampant throughout the medieval period and took a variety of forms. In 1462, it took the form of a decree issued by the Frankfurt Council which forced the Jews to live in a newly created ghetto. It was basically one long street, called the Judengasse, ultimately with four and five story wooden row-houses on both sides of the street (figures 2, 3, and 4).[19] Initially, walls 30 feet high were constructed around the ghetto to keep the Jews out of Christian Frankfurt. The gates that allowed entry in and exit from the ghetto were kept locked at night. Jews could not leave the ghetto on Sundays and Christian holidays (until 1798, when this restriction was rescinded). These were the basic conditions of Jewish life on Frankfurt until the 19th century, when in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Emancipation, the ghetto walls came crumpling down and Jews were permitted to live outside the ghetto.[20]

(Fig. 1) Briefly, when R. Samson Raphael Hirsch succeeded in creating a thriving separatist Orthodox Jewish community in Frankfurt in the 19th century (after the majority of the official Jewish community had joined the Reform movement), it became apparent to the official Jewish community that the best way to counter Hirsch’s success was by finding a place for Orthodoxy within the official Jewish community. The communal authorities agreed in 1878 to appoint an Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Markus Horovitz (author of שו”ת מטה לוי), aside from the Reform rabbis already in their employ. As a precondition to his appointment, Rabbi Horovitz demanded that a new Orthodox synagogue be built for his community in Frankfurt. It was constructed in 1882 – a magnificent structure – and was known as the Börneplatz Synagogue (figure 1) until its destruction by the Nazis on November 10, 1938.[15] Indeed, it was built adjacent to the Jewish cemetery, and its windows overlooked the tombstones in the cemetery. It displaced the old Jewish hospital, not a synagogue. No other synagogue in the history of Frankfurt was built overlooking the Jewish cemetery. This, then, was the synagogue that R. Tamar saw in 1921. But, of course, it didn’t exist in 1617 and therefore cannot be used to explain the accounts of R. Joseph Yuzpa Hahn and R. Asher b. Eliezer Ha-Levi.[16] Tamar’s confused account misled at least two of the recent halakhic anthologies on birkat ha-hammah, R. Gavriel Zinner, נטעי גבריאל: קידוש החמה וברכתה (Jerusalem, 2009)[17] and R. Yonah Buxbaum, קידוש החמה (Jerusalem, 2009).[18] Both cite Tamar’s account as authoritative, without further comment. In the case of R. Buxbaum (prior to his citation of Tamar), two reasons are suggested for the recitation of birkat ha-hammah adjacent to the Jewish cemetery: it provided greater space for the entire Jewish community to gather and recite the blessing together, and it provided a better view of the sun. At last, a breath of fresh air! We shall devote the remainder of this essay to an analysis of these two suggestions, to see whether or not they are likely explanations of what happened in Frankfurt. An organized Jewish community existed in Frankfurt from as early as 1150. Christian persecution of the Jews in Frankfurt was rampant throughout the medieval period and took a variety of forms. In 1462, it took the form of a decree issued by the Frankfurt Council which forced the Jews to live in a newly created ghetto. It was basically one long street, called the Judengasse, ultimately with four and five story wooden row-houses on both sides of the street (figures 2, 3, and 4).[19] Initially, walls 30 feet high were constructed around the ghetto to keep the Jews out of Christian Frankfurt. The gates that allowed entry in and exit from the ghetto were kept locked at night. Jews could not leave the ghetto on Sundays and Christian holidays (until 1798, when this restriction was rescinded). These were the basic conditions of Jewish life on Frankfurt until the 19th century, when in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Emancipation, the ghetto walls came crumpling down and Jews were permitted to live outside the ghetto.[20] (Fig. 2)

(Fig. 2) (Fig. 3)

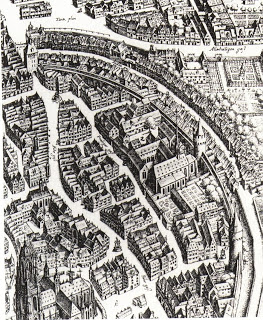

(Fig. 3) (Fig. 4) A wonderful account of the Judengasse is preserved in the writings of R. Jacob Joshua Falk (author of פני יהושע), who described what he saw when he moved to Frankfurt in 1742 in order to serve as Chief Rabbi:[21] בבאי לכאן ק”ק פפד”מ עיר הגדולה לאלקים, רבתי עם, רבתי בדעות, ראיתי שערוריה גדולה בין כהני ה’, בהיות הדבר ידוע שאין ליהודים פה כי אם רחבה אחת קטנה, ארוכה כמות שהיא מצפון לדרום ונחלקה לשתי שכונות, אחת מצד מזרח ושכנגדה למולה מצד מערב, ואין הפסק בין הבתים, כל שכונה ושכונה, כי אם במקומות מעט מזעיר. והיה כי ימות מת באחד מבתי השכונה, הוצרכו הכהנים להיות נעים ונדים ולזוז ממקום ולילך משכונה לשכונה שכנגדה. ואם ח”ו גם באותה שכונה ימות המת, אזי לא ימצא מנוח לכף רגלם, ללון לינה אחת ברחוב היהודים כלל, כי אם במקומות מעט מזעיר. Lest anyone assume that the פני יהושע’s description of the Judengasse applies only to the 18th century, and not earlier, a map of Frankfurt – drawn in 1628 – indicates otherwise (see figure 5).[22] The map, contemporary with R. Joseph Juzpa Hahn and R. Asher b. R. Eliezer Ha-Levi, depicts the Judengasse exactly as described by the פני יהושע.

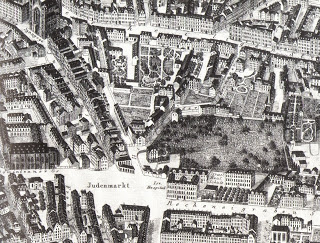

(Fig. 4) A wonderful account of the Judengasse is preserved in the writings of R. Jacob Joshua Falk (author of פני יהושע), who described what he saw when he moved to Frankfurt in 1742 in order to serve as Chief Rabbi:[21] בבאי לכאן ק”ק פפד”מ עיר הגדולה לאלקים, רבתי עם, רבתי בדעות, ראיתי שערוריה גדולה בין כהני ה’, בהיות הדבר ידוע שאין ליהודים פה כי אם רחבה אחת קטנה, ארוכה כמות שהיא מצפון לדרום ונחלקה לשתי שכונות, אחת מצד מזרח ושכנגדה למולה מצד מערב, ואין הפסק בין הבתים, כל שכונה ושכונה, כי אם במקומות מעט מזעיר. והיה כי ימות מת באחד מבתי השכונה, הוצרכו הכהנים להיות נעים ונדים ולזוז ממקום ולילך משכונה לשכונה שכנגדה. ואם ח”ו גם באותה שכונה ימות המת, אזי לא ימצא מנוח לכף רגלם, ללון לינה אחת ברחוב היהודים כלל, כי אם במקומות מעט מזעיר. Lest anyone assume that the פני יהושע’s description of the Judengasse applies only to the 18th century, and not earlier, a map of Frankfurt – drawn in 1628 – indicates otherwise (see figure 5).[22] The map, contemporary with R. Joseph Juzpa Hahn and R. Asher b. R. Eliezer Ha-Levi, depicts the Judengasse exactly as described by the פני יהושע. (Fig. 5) One other point needs to be addressed in order for this analysis to continue. What time in the morning did davening begin in Frankfurt, and when did they recite the birkat ha-hammah? Regarding the latter question, the two witnesses cited at the start of the essay seem to contradict each other. R. Joseph Yuzpa Hahn indicates that the blessing was recited immediately after davening, adjacent to the cemetery. R. Asher b. R. Eliezer Ha-Levi indicates that it was recited “in the third hour,” adjacent to the cemetery. In fact, we know that on April 5, 1617, sunrise (more specifically: נץ החמה) in Frankfurt was at 5:53 A.M. and sunset was at 7:03 P.M.[23] If one counted hours from 6:00 A.M., the third hour was between 8:00 and 9:00 A.M. If one counted שעות זמניות, the third hour from sunrise was approximately between 8:05 and 9:11 A.M. We also know exactly what time davening ordinarily began, thanks to Johann Jacob Schudt, who testifies that services began every weekday morning in Frankfurt at 6:00 A.M.[24] Assuming that davening took not more than an hour, according to R. Hahn the blessing was recited shortly after 7:00 A.M. According to R. Ha-Levi it was recited shortly after 8:00 A.M.[25] At that hour, on the Judengasse, due to the row-houses, the sun could not be seen at all! This was because the Judengasse was a crescent shaped street on a North-South axis, more or less perpendicular to the Main River. In order to see the sun – rising in the East and setting in the West – it was necessary to leave the ghetto and walk to the nearest open space, so that the blessing could be properly recited. The nearest open space, just beyond the southern gate of the ghetto, was the Jewish cemetery and its surrounding fields (see figure 6).[26]

(Fig. 5) One other point needs to be addressed in order for this analysis to continue. What time in the morning did davening begin in Frankfurt, and when did they recite the birkat ha-hammah? Regarding the latter question, the two witnesses cited at the start of the essay seem to contradict each other. R. Joseph Yuzpa Hahn indicates that the blessing was recited immediately after davening, adjacent to the cemetery. R. Asher b. R. Eliezer Ha-Levi indicates that it was recited “in the third hour,” adjacent to the cemetery. In fact, we know that on April 5, 1617, sunrise (more specifically: נץ החמה) in Frankfurt was at 5:53 A.M. and sunset was at 7:03 P.M.[23] If one counted hours from 6:00 A.M., the third hour was between 8:00 and 9:00 A.M. If one counted שעות זמניות, the third hour from sunrise was approximately between 8:05 and 9:11 A.M. We also know exactly what time davening ordinarily began, thanks to Johann Jacob Schudt, who testifies that services began every weekday morning in Frankfurt at 6:00 A.M.[24] Assuming that davening took not more than an hour, according to R. Hahn the blessing was recited shortly after 7:00 A.M. According to R. Ha-Levi it was recited shortly after 8:00 A.M.[25] At that hour, on the Judengasse, due to the row-houses, the sun could not be seen at all! This was because the Judengasse was a crescent shaped street on a North-South axis, more or less perpendicular to the Main River. In order to see the sun – rising in the East and setting in the West – it was necessary to leave the ghetto and walk to the nearest open space, so that the blessing could be properly recited. The nearest open space, just beyond the southern gate of the ghetto, was the Jewish cemetery and its surrounding fields (see figure 6).[26] (Fig. 6) Returning to the two suggestions of R. Buxbaum, the first was that the land adjacent to the cemetery provided greater space for the entire Jewish community to gather and recite the blessing together. Doubtless this is true, but it does not seem likely that this was the key factor for the decision to walk out to the cemetery area. There was one place in the Jewish ghetto where large crowds could gather, if the only concern was ברוב עם הדרת מלך. Weddings in Jewish Frankfurt were performed just outside the doors of the main synagogue[27] precisely because there was sufficient room for all the invited guests to attend the ceremony (see figure 7).[28] In 1617, there were some 454 Jewish families living in Frankfurt.[29] These could easily gather in front of the main synagogue, if necessary in shifts. If they walked to the cemetery area nonetheless, it was because only there could the sun be sighted and the blessing recited. R. Buxbaum’s second suggestion was that the cemetery area provided “a better view” of the sun. We would suggest that it provided the only view of the sun – at an early hour – in Jewish Frankfurt from the 15th through the 19th centuries.

(Fig. 6) Returning to the two suggestions of R. Buxbaum, the first was that the land adjacent to the cemetery provided greater space for the entire Jewish community to gather and recite the blessing together. Doubtless this is true, but it does not seem likely that this was the key factor for the decision to walk out to the cemetery area. There was one place in the Jewish ghetto where large crowds could gather, if the only concern was ברוב עם הדרת מלך. Weddings in Jewish Frankfurt were performed just outside the doors of the main synagogue[27] precisely because there was sufficient room for all the invited guests to attend the ceremony (see figure 7).[28] In 1617, there were some 454 Jewish families living in Frankfurt.[29] These could easily gather in front of the main synagogue, if necessary in shifts. If they walked to the cemetery area nonetheless, it was because only there could the sun be sighted and the blessing recited. R. Buxbaum’s second suggestion was that the cemetery area provided “a better view” of the sun. We would suggest that it provided the only view of the sun – at an early hour – in Jewish Frankfurt from the 15th through the 19th centuries. (Fig. 7) It is noteworthy that some 30,000 Jews lived in Frankfurt in 1925, a year in which birkat ha-hammah was recited. There are no reports that Jews went to the cemetery area in order to recite the blessing. It was no longer necessary.

(Fig. 7) It is noteworthy that some 30,000 Jews lived in Frankfurt in 1925, a year in which birkat ha-hammah was recited. There are no reports that Jews went to the cemetery area in order to recite the blessing. It was no longer necessary.[1] A third witness from Frankfurt, R. Joseph Koshmann, נהג כצאן יוסף (Hanau, 1718; cf. the Tel-Aviv, 1969 edition, p. 145), also discusses birkat ha-hammah. Since he makes no reference to the Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt, the focus of discussion of this essay, his account will not be addressed.[2] The correct name of the sefer is יוסיף אומץ. The printer misread the manuscript copy (still extant at the Bodleian Library in Oxford), and it is by the mistaken title that the book is read and cited. See R. Yissachar Tamar,עלי תמר: ירושלמי סדר זרעים (Tel-Aviv, 1979), vol. 1, p. 294. [3] . §378. Cf. יוסף אומץ (Frankfurt, 1928), p. 80, §378. R. Hahn’s testimony is not necessarily confined to the 1617 recital of the birkat ha-hammah, as he may also have witnessed the 1589 recital when he was 19 years old. [4]. P. 7 of the Hebrew section of M. Ginsburger, ed., Die Memoiren des Ascher Levy (Berlin, 1913). Cf. E. Kallmann, ed., Les Mémoirs d’Ascher Levy de Reichshoffen (Paris, 2003), p. 21, interlinear addition 2. [5] Cf. Psalm 137:1 על נהרות בבל, which can only mean “at the side of; by.” See also Rashi to Gen. 14:6. [6] See, e.g., E. Brodt and Ish Sefer, “A Preliminary Bibliography of the Recent Works on Birkat ha-Chamah,” Tradition Seforim Blog, March 27, 2009; and Akavya Shemesh, “על ספר קידוש החמה לר’ יונה בר”י בוקסבוים,” Tradition Seforim Blog, March 30, 2009. [7] We have examined the following 6 works only: R. J. David Bleich, Bircas HaChammah (Brooklyn, 2009); R. Yonah Buxbaum, קידוש החמה (Shikun Square, 2009); R. Mordechai Genut, ברכת החמה בתקופתה (Bnei Brak, 2009); R. Menachem Mendel Gerlitz, ברכת החמה כהלכתה (Jerusalem, 2009); R. Yehuda Herskowitz,The Sun Cycle (Monsey, 2009); and R. Gavriel Zinner, נטעי גבריאל: הלכות ברכות החמה (Brooklyn, 2009). [8] Genut, p. 290. [9] Had there been any validity to this presumption, it surely would have been adduced by the late R. Mordechai Spielman in his ציון לנפש צבי (Brooklyn, 1976), an anthology of all passages in rabbinic literature that allow a Kohen to enter a cemetery.[10] See שולחן ערוך: יורה דעה §367:2-4 and commentaries. [11] Gerlitz, p. 232 was the only work (of the 6 I consulted) to raise this issue (in a footnote). He resolves it by suggesting that the blessing was actually recited just outside the cemetery. Nonetheless, in the body of his work he writes unequivocally that: יש שנהגו לברך ברכה זו בבית הקברות.[12] So too Gerlitz, pp. 231-232.[13] See above, note 2. [14] For this emendation, see already R. Liepman Philip Prins (d. 1915), פרנס לדורות (Jerusalem, 1999), p. 292. [15] See Rachel Heuberger and Salomon Korn, The Synagogue at Frankfurt’s Börneplatz (Frankfurt, 1996). Figure 1, a photograph of the Börneplatz Synagogue taken in 1887, is drawn from p. 11 of this booklet. [16] Moreover, the Börneplatz Synagogue was outside the Jewish ghetto, whereas during the ghetto period (15th -19th centuries), all the synagogues in Frankfurt were inside the ghetto. [17] Pages 105-106.[18] Pages 160-161.[19] Figure 2 is a 19th century lithograph of the Judengasse (from the Leiman Library). Figure 3 is a photograph of the Judengasse from circa 1860 and is drawn from Georg Heuberger, Ludwig Börne – A Frankfurt Jew Who Fought For Freedom (Frankfurt, 1996), p. 9. Figure 4 is a photograph of the eastern side of the Judengasse, taken circa 1875 after much of the western side was demolished. The main Reform Synagogue, constructed in 1860 at the exact site where the main synagogue of the traditional community once stood, can be seen at the extreme left of the photograph (from the Leiman Library). [20] In general, see A. Freimann and F. Kracauer, Frankfort (Philadelphia, 1929). [21] See R. Mordechai Halberstadt, שו”ת מאמר מרדכי (Brünn, 1790), §56. [22] The map is drawn from Rachel Heuberger and Helga Krohn, Hinaus aus dem Ghetto: Juden in Frankfurt am Main 1800-1950 (Frankfurt, 1988), p. 13. [23] See R. Meir Posen, אור מאיר (London, 1973), p. 330 and table 86. [24] Johann Jacob Schudt, Jüdische Merkwürdigkeiten (Frankfurt, 1714), vol. 2, p. 218. [25] It is possible that in order to recite birkat ha-hammah together as a community specifically during the third hour, davening in Frankfurt on this day began at 7:00 A.M., rather than at 6:00 A.M. Thus, there would be no conflict between the reports of R. Hahn and R. Ha-Levi, both agreeing that the blessing was recited shortly after 8:00 A.M. Interestingly, a לוח published in Frankfurt in 1757 – a year in which birkat ha-hammah was recited – seems to state that the proper time for the recital of the blessing was between 8:00 and 10:00 A.M (if I am reading it correctly). I am indebted to Dan Rabinowitz for bringing the לוח to my attention. [26] Figure 6 is a portion of a map of Frankfurt from 1864. It is drawn from Heuberger and Krohn, op. cit., p. 93. At the upper left of the map is the Judengasse. One can see the newly constructed Reform Synagogue on the eastern side of the Judengasse.. The row-houses lead into the Judenmarkt, east of which is the old Jewish cemetery. Doubtless, it was in and around the Judenmarkt that the Jews gathered to recite birkat ha-hammah between the 15th and 19th centuries. [27] See סדר והנהגה של נשואין (Frankfurt, 1701), pp. 4-5, §4. Cf. יוסף אומץ (Frankfurt, 1928), p. 332.[28] Figure 7 (drawn from Heuberger and Krohn, op. cit., p. 49) depicts the Old Synagogue (on the Judengasse) of Frankfurt, after it was rebuilt in 1711 [and prior to its demolition in 1860] following a fire that destroyed almost all the dwellings in the Jewish ghetto. There appears to be ample space in the foreground for the communal recitation of birkat ha-hammah. [29] See Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 5, p. 486.