Franciscans and More; “Repulsive” Practices; Saul Lieberman, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Franciscans and More; “Repulsive” Practices; Saul Lieberman, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Marc B. Shapiro

1. Following up on what I wrote here and here about the term צעירים (Franciscans) and other expressions used with reference to Catholic religious orders, Brian Schwartz called my attention to a couple of relevant sources. In Milhemet Hovah (Constantinople, 1710), p. 14a, R. David Kimhi mentions a theological argument he had with one of the חכמי הצעירים. In Ginzei Nistarot (1868), vol. 2, p. 10, R. Jacob of Venice in his anti-Christian polemic mentions the צעירים and the דורשים (Dominicans). I also found a mention in the text of the Tortosa Disputation, ibid., p. 47. R. David Kimhi refers to the צעירים and the דורשים in his letter about the Maimonidean controversy found in Kovetz Teshuvot ha-Rambam ve-Igrotav, sec. 3 (Iggerot Kanaut), p. 4.[1]

There are no doubt many other such references in medieval texts and there is no need to elaborate any further. However, there is one other point worth noting. In the version of Nahmanides’ Disputation printed in Judah Eisenstein, Otzar Vikukhim, p. 89, it reads: וחכמי הצעירים והדורשים והחובלים. The last word, החובלים, is not found in the version published in Chavel’s edition. What does החובלים mean?

In his note Eisenstein tells us that החובלים are Cordeliers, which is how the Franciscans were called in France.[2] In fact, the Cordeliers were only one branch of the larger Franciscan order. The word cordelier refers to the rope that Franciscans wore around their waist.

חובלים, together with Cordeliers, appears in R. Avigdor Tzarfati’s Torah commentary:[3]

מכאן רמזה תורה אותן החובלים קירדליי”ש והייקופינ”ט ההולכים יחפים שעתידין להכעיס את ישראל

In this text we also have a new word, הייקופינ”ט. This is just an alternate spelling of the word יקופש. In Da’at Zekenim mi-Ba’alei ha-Tosafot, Deut. 32:21, it refers to החובלים ויקופש as people who bring trouble upon the Jews. So what does this word יקופש mean? In R. Aharon Yehoshua Pessin’s Midah ke-Neged Midah [4] he knows that החובלים refers to Franciscans and suggests that יקופש means “Capuchin.” However, the Capuchin order, which is a branch of the Franciscans, was only founded in the sixteenth century, so the Tosafists could not have mentioned it. יקופש actually refers to the Jacobins,[5] which is how the Dominicans were called in medieval France.

2. Readers might recall that in my post here I mentioned the late Dr. Shlomo Sprecher’s characterization of two segulot as “repulsive.”[6] I then cited another example of a segulah which I believe falls into this category (and see also my post here). However, the obvious point, which I mention here, is that what our generation regards as repulsive was not always regarded so in a different generation and culture.

Following the post in which I discussed Dr. Sprecher’s article, a few people sent me examples of things that were accepted in previous generations but today would be regarded as repulsive. Many of these examples are from general society and relate to standards of hygiene, food, etc., but a few came from Jewish texts as well. One reader sent me this interesting post by Tomer Persico that deals with the matter. He mentions, among other things, the following shocking remedy recorded in R. Hayyim Vital, Sefer ha-Peulot, p. 321, that appears to recommend a blatant halakhic violation. (It is doubly shocking when one remembers how seriously this sin is viewed in Lurianic Kabbalah, and this fact alone should perhaps lead us to reject the authenticity of the comment.)

לנכפה [לריפוי אדם הסובל ממחלת הנפילה], יקחו נער א’ [אחד] שמימיו לא ראה קרי ויוציאו ממנו שכבת זרע, ואותו הקרי ושכבת הזרע ימשחו בו שפתותיו של החולה ומעולם לא יחזור החולי ההוא

Jeremy Brown, in his recent National Jewish Book award winning volume, The Eleventh Plague: Jews and Pandemics from the Bible to COVID-19 (Oxford, 2023), p. 77, mentions another recommendation, this time to avoid bubonic plague. Among the ingredients to be consumed are “a little of the first urine” produced in the morning and “a small quantity of dried human feces, dissolved in wine or rose water, to be taken while fasting.”[7]

In the post here referred to above, I dealt with metzitzah ba-peh. Subsequently, I found that R. Leon Modena, in his response to the heretic Uriel da Costa, rejects the latter’s claim that metzitzah ba-peh is disgusting because the mouth speaks the word of God while the sexual organ is impure.[8] The medieval anti-Jewish polemicist, Raymond Martini, had earlier attacked metzitzah ba-peh as an “abominable act.”[9]

R. Moshe Mordechai Epstein has a perspective at odds with many other Lithuanian sages in seeing metzitzah as essential to the mitzvah of circumcision, not simply a medical procedure.[10] He also sees metzitzah ba-peh as crucial to the fulfilment of this mitzvah, again, in opposition to what was the standard approach in Lithuania (as opposed to among the Hasidim). As he puts it, if metzitzah ba-peh is not a basic part of the mitzvah, no one would have ever advocated such an action that, in any other circumstance, would be regarded as utterly repulsive.

אשאל שאלה מאלה האומרים כי מציצה היא רק משום סכנה, וע”כ די ברטית סמרטוטין, מאותם אשאל, נשער נא בנפשינו, אילו לא הי’ מצוה ולא הי’ נהוג אצלינו לעשות המציצה, ואחד הי’ רוצה לעשות המציצה בפה, בודאי היינו קוראים אחריו מלא כי אין לך מתועב יותר מזה ליקח אבר פצוע לתוך הפה. ומה גם אותו האבר. ולא עוד אלא למצוץ הדם, הלא הדבר גועל נפש ממש חלילה (אם אינה מצוה) . . . מי זה חסר לב יאמר כי הנהיגו דבר כזה בלי מצוה . . . בענין המציצה כאשר היא מצוה קדושה לתקן הנפש, אין בה גיעול ח”ו, קדושה וטהורה היא המצוה, אהובה וחביבה מרוממת רוחניות הנפש, אבל אילו לא הי’ מצוה רק הכשר כדי שלא יסתכן הולד מהדם, איך נוכל לומר שיהי’ נהוג בישראל ענין מתועב כזה, חלילה וחלילה. הלא האמת ברור לכל, כי המציצה היא מצוה קדושה בעצמה דוקא באופן הזה למצוץ דוקא בפה

3. In my last post here I spoke about Saul Lieberman, so let me add a few more points. In Tovia Preschel’s Ma’amrei Tuvyah, vol. 6, p. 231, he discusses Lieberman’s investigations into obscure words in rabbinic literature, and is reminded of how Sherlock Holmes can always find the answer:

כשאתה רואה אותו מצרף קו לקו ותג ותג להוכחה ברורה ומוריד מעל המלים את המסווה שמאחוריו מתחבאת משמעותן האמיתית – עולה בלבך המחשבה: הרי זה שרלוק הולמס, האמן-הבלש, של שפתנו

ואמנם נקראים כמה ממחקריו בענייני לשון כסיפורים של סר ארתור קונן דויל. דומה עליך שהנך רואה את שרלוק הולמס מרצה לידידו ועוזרו ואטסון כיצד סימנים ועקבות קטנים ובלתי-ברורים מוליכים אותו לפענוחו של תעלומות גדולות

ר’ שאול ליברמן – תורה למד בישיבות, חכמה קנה באוניברסיטאות – אך אמנות הבלשות מנין לו

Preschel then notes that in the little free time that Jabotinsky had, he liked to read detective stories. Preschel wonders, does Lieberman also do so? He adds that he was never brazen enough to ask Lieberman about this.

לפעמים אני הוגה בלבי: אולי גם ר’ שאול בין קוראי ספרות זו, עת הוא נח מעמלה של תורה, בשעה שאינה לא יום ולא לילה? אך עדיין לא העזתי לשאול אותו כל כך

Preschel’s insight is amazing. In Lieberman’s letter to Gershom Scholem, dated July 31, 1947,[11] Lieberman writes about how during the summer vacation, when he is away from New York and has free time, he reads detective stories![12]

ומכיוון שבכפר אני מתיר לעצמי לבטל קצת את הזמן הריני קורא לפעמים ספרות בלשית. וכשבא מאמרך לידי נמשכתי אחריו באותה מתיחות ממש כאילו אני קורא a detective story

Earlier in Ma’amrei Tuvyah, vol. 6, pp. 229-230, Preschel provides the answer to something I had thought about. If you look at a number of the title pages of Lieberman’s books you see that his name is in smaller print than that of his father.

Other than in Lieberman’s books, I don’t recall ever seeing this on a title page. Fortunately, Preschel asked Lieberman about this and Lieberman explained that this is “minhag Yisrael”. Lieberman showed Preschel what R. Hayyim Benveniste writes in Sheyarei Kenesset ha-Gedolah, Tur, Yoreh Deah 240:8, that when one signs his name together with that of his father, yesh nohagim that the father’s name is written above as a sign of respect. What this means is that the father’s name written with bigger letters so that it stretches above the son’s name.

Here is the page in R. Benveniste’s work where he also provides an example.

Preschel concludes:

“פותח שערים” אני. אצבעותי מישמשו בהרבה ספרים. שערים רבים ראיתי. צא ובדוק אם תמצא מחברים שנהגו מנהג רם ונשגב זה בשערי ספריהם. ואם תמצא – מעטים הם, נער יספרם

Since we have been speaking about Lieberman, here is a treat for all the Lieberman fans: A letter from Lieberman to Abraham Joshua Heschel in which we see a bit of Lieberman’s mischievous humor.[13]

And while mentioning Heschel, here is another letter to him from R. Pinchas Biberfeld.[14]

From this letter we learn something that until now was completely unknown, namely, that Heschel attended lectures of R. Jakob Freimann at the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary. In Edward Kaplan’s book on Heschel, Prophetic Witness, pp. 106, 256, he mentions that Heschel would frequently eat at Freimann’s house on Shabbat, and that Heschel contributed an article — his first academic publication — to the Freimann Festschrift.

R. Pinchas Biberfeld was the son of the legendary physician-rabbi Eduard Biberfeld, and he received semikhah from the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary. Here is a copy of his semikhah.[15]

The semikhah, dated Feb. 7, 1939, is signed by R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg and R. Samuel Gruenberg. R. Weinberg was forced to leave Germany not long after this, and R. Gruenberg and R. Biberfeld were fortunate to also get out and immigrate to Eretz Yisrael. While in Israel R. Biberfeld edited the Torah journal Ha-Ne’eman. You can read about him here on Wikipedia, and here is an interview he gave.

Biberfeld’s German name was Paul, and he was named after Paul von Hindenburg![16] People today often don’t realize how integrated into German society the German Orthodox were, and the naming of Paul Biberfeld is a great example of this.[17] In some ways, the German Orthodox were even more attached to their non-Jewish surroundings than today’s American Modern Orthodox, whose Americanness is usually expressed in a shared low culture with non-Jewish society (e.g., television, music, and sports), rather than in high culture and patriotism, both of which were part of the German Orthodox ethos.

R. Immanuel Jakobovits’s father was a well-known German rabbi, Julius Jakobovits, and yet he was comfortable naming his son after Immanuel Kant.[18] (R. Jakobovits’s Hebrew name was Yisrael.) In Michael Shashar, Lord Jakobovits in Conversation, pp. 10-11, Jakobovits explains (and it is obvious that he did not know the story of Paul Biberfeld’s name):

I may be the only rabbi in the world named after a non-Jew – Immanuel Kant, who was a native of Koenigsberg [where Jakobovits was born] and never left it.[19] The city was also known as “Kantstadt” [the city of Kant]. My father was one of Kant’s admirers, and when I was born he wanted to call me Israel, after one of his uncles, but at that time in Germany it was not acceptable to call a Jewish child Israel. Accordingly, he searched for a name beginning with I and ending with L, and so he gave me Kant’s name, Immanuel.

I don’t know why it was not acceptable in 1920s Germany for a Jewish child’s “secular” name to be Israel.

Returning to Heschel, when he first came to the United States he was teaching at the Reform Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. Here is a letter from Louis Ginzberg to Heschel that provides information that until now has not been known.[20]

From this letter, we see that Heschel was in discussions about a job at Dropsie College. Ginzberg urges him to accept this position if offered, and notes that the atmosphere at HUC was not in line with Heschel’s outlook. This never came to be, and Heschel accepted a position at the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1946 where he spent the rest of his life.

I think readers will find the next two letters of interest, as we see that Heschel was in discussions to teach at Yeshiva College and its Bernard Revel Graduate School.[21]

There are two other documents from the Heschel Archives that I would like to call attention to as they are of great historical interest. Unfortunately, they were not available to me when I wrote Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy. First, I must note that a few months ago the Jewish Historical Institute of Warsaw published a wartime list of rabbis in the Warsaw Ghetto. You can see it here. The list is not complete. For one, it does not mention R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, whom as I discuss in Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy was very involved in the Warsaw ghetto rabbinate and also served as the head of a committee to assist rabbis and yeshiva students. Also not mentioned in the Hebrew document is R. Kalonymous Kalman Shapiro, the Piaseczno Rebbe.

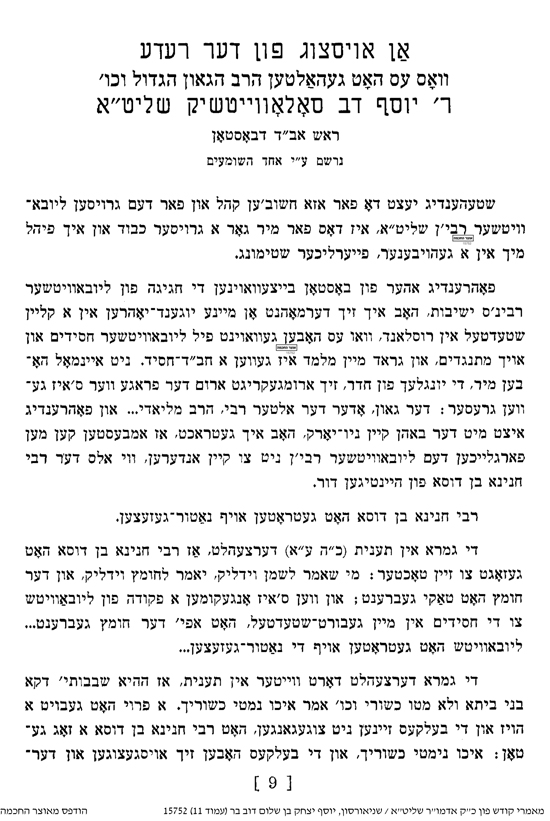

In a letter dated May 25, 1941, R. Weinberg wrote to Heschel from the Warsaw Ghetto.[22] Here is the envelope that R. Weinberg used. I include both sides of the envelope. As you can see, Heschel was living at Henry Street on the Lower East Side. Also note R. Weinberg’s address on the reverse as well as the Nazi stamp.

Here is the letter in which R. Weinberg asks Heschel for assistance with the emigration of rabbis in the ghetto. Because of German censorship, R. Weinberg’s letter had to be written in German. (We have other letters from R. Weinberg sent from the Ghetto and they too are written in German.)

It is interesting to see how R. Weinberg’s letter divides the rabbis between the truly outstanding and the others who, while also praised, are placed on a lower level. (R. Kalonymous Kalman Shapiro does not appear on the list.) While in the end, none of the rabbis were permitted to emigrate, the letter is clearly making a distinction between the rabbis. It is saying that if only limited opportunities to emigrate are available, that the order should be the rabbis in list 1, followed by list 2, and then list 3 and 4. This is a clear case where the greater rabbis were going to be saved first.[23]

The letter we have just seen, which is not addressed to a particular individual, and also the letter below, were sent to a number of people, not specifically to Heschel. You can see this in the letter below by how Heschel’s name is inserted at the beginning. Yet I have never seen other copies, which is why we have to be grateful that Heschel saved everything.

In a letter dated June 15, 1941, R. Weinberg again wrote to Heschel from the Warsaw Ghetto. Here are both sides of the envelope, followed by the letter, and this time R. Weinberg spelled the street name “Henry” correctly.

In this letter, R. Weinberg speaks about American Jewish assistance in sending money and food, and helping with emigration from Warsaw. The letter is accompanied by two lists, lengthier than what we saw in the first letter, divided again into what may be the more important figures and the others. But I am not certain if this is the significance of the division here, as there are some differences in how the names are divided in the two letters.

On the first list here you can see R. Kalonymus Kalman Shapiro at no. 20, with his address — that we know from other sources as well — 5 Dzielna. Other than R. Weinberg, did any of the rabbis on the two lists survive?

* * * * * * *

[1] This letter is difficult to read, as the sage he degrades for informing on Maimonides to the Church may be R. Jonah Gerondi.

[2] See also Ben Yehudah’s dictionary, s.v. חובל; Dov Yarden, “Hovel Nazir Franciscani,” Leshonenu 18 (1953), pp. 179-180.

[3] Perushim u-Fesakim le-Rabbenu Avigdor ha-Tzarfati (Jerusalem, 1996), p. 445.

[4] (Jerusalem, 2009), p. 157 n. 20.

[5] See Leopold Zunz, Zur Geschichte und Literature (Berlin, 1845), p. 181.

[6] One of these segulot is that barren women should swallow the foreskin of newly circumcised boys in order to help them conceive a male child. For more sources on this practice, see Zev Wolf Zicherman, Otzar Pelaot ha-Torah, vol. 4, pp. 486-487. R. Yehoshua Mamon, Emek Yehoshua, vol. 1, Yoreh Deah, nos. 31-32, argues that this practice is forbidden according to Torah law. Regarding mohalim being buried with the foreskins they cut off, as a form of protection after death, see R. Joseph Messas, Otzar ha-Mikhtavim, vol. 2, no 986. Regarding women consuming the placenta, see R. Mordechai Lebhar, Menuhat Mordechai, no. 38.

[7] Regarding eating portions of a corpse and ground-up skull of non-Jews, and why rabbis permitted this, see my post here. Repulsive language is also noteworthy. R. Uri Feivish Hamburger, Urim ve-Tumim (London, 1707), p. 8a, first word of line 3, is the only example I know where a certain inappropriate word appears in a sefer. According to this source, even in the early eighteenth century the word was regarded as taboo.

It could be that this word is no longer really regarded as repulsive, only a little unseemly. It even appears in the title of eminent philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt’s #1 New York Times bestselling book, published by Princeton University Press. See here.

While Jews are obligated to speak in a dignified manner, there is an exception when it comes to speaking about idolatry. See Megillah 25b, where among other things it states: “It is permitted for a Jew to say to a gentile: Take your idol and put it in your shin tav [i.e., shet, buttocks].” This is the Koren translation and Soncino and Artscroll translate similarly. Yet I was very surprised to find that in Shabbat 41a Soncino twice translates כנגד פניו של מטה as “near his buttocks”, when it is obvious that the proper translation is “over his genitals”.

[8] Magen ve-Tzinah, p. 6b. Let me take this opportunity to correct a common error. R. Leon Modena called himself Yehudah Aryeh mi-Modena. But in Italian he called himself Leon Modena (not Leon de Modena). Modena himself tells us this. See Hayyei Yehudah, ed. Daniel Carpi (Tel Aviv, 1985), p. 33:

אני חותם עצמי בנוצרי ‘ליאון מודינא דה ויניציאה‘, ולא דה מודינא‘, כי נשארה לנו העיר לכנוי ולא לארץ מולדתנו, וכן תמצא בחבורַי הנוצרים בדפוס

[9] See Lawrence Osborne, Poisoned Embrace: A Brief History of Sexual Pessimism (New York, 1993), p. 128. Regarding Martini, see Richard S. Harvey, “Raymundus Martini and the Pugio Fidei: A Survey of the Life and Works of a Medieval Controversialist” (unpublished masters dissertation, University College London), available here. Shimon Steinmetz pointed out to me that the famous non-Jewish Hebraist Johann Buxtorf (1564-1629), in his discussion of metzitzah, does not express any revulsion. He merely notes that this was not commanded by Moses. See here. It would be interesting to examine how other Christian scholars and Jewish apostates of previous centuries described metzitzah.

[10] She’elot u-Teshuvot Levush Mordechai, no. 30. The expression he uses in the passage, קוראים אחריו מלא, comes from Jer. 12:6.

[11] The letter was published by Aviad Hacohen, “Ha-Tanna mi-New York,” Madaei ha-Yahadut 42 (5763-5764), p. 298.

[12] After I wrote this, I learned that R. Yitchak Roness made the exact same point. See here.

[13] The original is found in the Heschel Archives, Duke University, Box 2, Folder 2.

[14] The original is found in the Heschel Archives, Duke University, Box 10, Folder 3.

[15] The original is found in the Leo Baeck Institute; see here.

[16] See Mordechai Breuer, Modernity Within Tradition (New York, 1992), p. 480 n. 124. Breuer also mentions that a hasidic synagogue in Leipzig was renamed the “Hindenburg Synagogue.”

[17] See Jacob H. Sinason, The Rebbe : The Story of Rabbi Esriel Glei-Hildesheimer (New York, 1996), p. 128:

[Dr. Eduard Biberfeld] looked at the war against the Czar’s Russian empire as a kind of holy war against the dark forces responsible for the systematic persecution of Jews. He named one of his sons after the victorious German general, just as the Jews in Hellenistic times had called their children after Alexander the great. (Even to the extent of adopting Alexander as the Shem Hakodesh.)

The last sentence means that people with the name Alexander would be called up to the Torah with this name, as they would not have a corresponding Hebrew name as was often the case with German Orthodox Jews who had both a “secular” name and also a Hebrew name.

[18] Regarding Kant, Dr. Isaac Breuer had a picture of him on his wall, together with R. Samson Raphael Hirsch. I asked Breuer’s son, Prof. Mordechai Breuer, if the Holocaust had any effect on how he viewed Kant, who was, after all, an important part of German culture. As I expected, his answer was “no,” and even after the Holocaust the picture of Kant was not taken down.

The pictures on one’s walls obviously reflect an outlook. Alexander Altmann writes as follows about his father, R. Adolf Altmann, Rabbi of Trier:

Significantly, five pictures adorned his study, those of the “Hatam Sofer”, S.R. Hirsch, Graetz, Herzl and Mendelssohn, representing the orthodox tradition, old and new, Jewish History, the Zionist dream, and the philosophical quest respectively. These images had been the formative influences of his youth, and they continued to guide him.

“Adolf Altmann (1879-1944), A Filial Memoir,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 26 (1981), p. 160.

[19] Although often repeated, this is actually incorrect. We know that Kant did leave Koenigsberg on a few occasions, including for his father’s funeral, but he never was more than 30 miles or so from his home. I mentioned this in one of my classes on R. Elijah Benamozegh, see here, while referring to the report the latter only left Livorno twice in his life.

[20] The original is found in the Heschel Archives, Duke University, Box 20, Folder 2.

[21] The originals are found in the Heschel Archives, Duke University, Box 22, Folder 2. These letters are referred to in Edward K. Kaplan, Spiritual Radical: Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940-1972 (New Haven, 2007), pp. 61, 65.

[22] The Weinberg letters in are found in the Heschel Archives, Duke University, Box 22, Folder 2.

[23] For another example where rabbis (and their families) were chosen to be saved before others, see Steven Lapidus, “Memoirs of a Refugee: The Travels and Travails of Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung,” Canadian Jewish Studies 27 (2019), pp. 73-74. Lapidus quotes from a letter from R. Oscar Fasman, at that time in Ottawa:

Here we are not dealing with only seventy individuals. These seventy embody a wealth of Jewish sacred learning, the like of which can no longer be duplicated, now that the European Yeshivoth are closed. In these people we have that intensive tradition of Torah which buoyed up the spirit of Israel. Thus, we are saving not merely people, but a holy culture which cannot be otherwise preserved. When the U.S. admitted Einstein, and not a million other very honest and good people who asked for admission, the principle was the same. It is certainly horrible to save only a few, but when one is faced with a problem of so ghastly a nature, he must find the courage to rescue what is more irreplaceable.

-Heschel%201c%20small.jpg)

-Heschel%201d%20small.jpg)