The Religious-Zionist Manifesto of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya

by Bezalel Naor

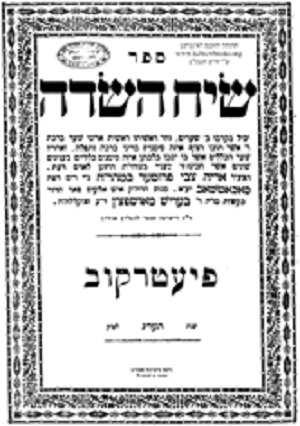

In 1901 there appeared in Vilna a 32-page booklet entitled, Ha-Tsiyoniyut mi-nekudat hashkafat ha-dat (Zionism from the Viewpoint of Religion). The author was Yehudah Don Yahya.[1] The final eight pages of the work contain a supplement (Milu’im) by one Ben-Zion Vilner, criticizing the anti-Zionism of the Rebbe of Lubavitch. (One ventures that “Ben-Zion Vilner” is a pseudonym.)

What is remarkable about this manifesto that argues that Zionism is totally compatible with traditional Judaism, is that the author, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya, was an intimate student of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik, a most outspoken opponent of the Zionist movement.[2]

To add to the intrigue, Don Yahya’s grandfather, Rabbi Shabtai Don Yahya of Drissa, had been an ardent Hasid of Rabbi Menahem Mendel of Lubavitch (known by his work of Halakhic responsa as “Tsemah Tsedek”).[3] Yehudah Leib himself would go on to serve as rabbi of the Habad Hasidic community of Shklov.[4] Although, as we shall see, within the Habad community, there were differing responses to Zionism along the fault line of the Kopyst—Lubavitch dispute.

Today, students who immerse themselves in the Torah novellae of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik may come across the name of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya, but they have no idea who this disciple was. Appended to Hiddushei ha-GRaH he-Hadash ‘al ha-Shas (issued upon the ninetieth anniversary of Rabbi Hayyim’s passing in 2008) are Don Yahya’s memoirs of his beloved mentor in the Volozhin Yeshivah. In 2018 (coincidentally a century since Rabbi Hayyim’s passing) there appeared in print a Tagbuch or diary, in which Rabbi Hayyim jotted down his insights on Talmud and Maimonides’ code.[5] In his introduction to the volume, the editor, Rabbi Yitshak Abba Lichtenstein, notes that Rabbi Hayyim would allow some scholars to copy down entries from the journal. Indeed, one such scholar was Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya. Two novellae that appear in the Tagbuch were previously published in Don Yahya’s Bikkurei Yehudah (1939).[6]

One asks: What would prompt such a devoted disciple to break from his master’s ideology concerning Zionism?

To understand how such a phenomenon as Yehudah Leib Don Yahya was possible, one needs to trace his membership in Nes Ziyonah, the underground proto-Zionist movement that existed in the Volozhin Yeshivah from 1885 until its disbandment in 1890.let

This was the era of Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion), a Russian Jewish movement to settle the Land of Israel that predated Herzlian political Zionism. Nes Ziyonah, which blossomed independently within the ranks of the student body of the famed Volozhin Yeshivah, interfaced with Hovevei Zion, presided over by Rabbi Samuel Mohilever of Bialystok. Members of Nes Ziyonah were sworn to secrecy. The membership included such illustrious scholars as Moshe Mordechai Epstein of Bakst,[7] Menahem Krakovsky,[8] and Isser Zalman Meltzer. Moshe Mordechai Epstein would eventually become Rosh Yeshivah of Slabodka. Menahem Krakowsky would one day assume the position of “Shtodt Maggid” of Vilna. Finally, Isser Zalman Meltzer would become Rosh Yeshivah of Slutzk and later ‘Ets Hayyim of Jerusalem.[9] It was through the last-mentioned disciple, who was especially close to Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik, that Rabbi Hayyim was able to discover the identities of the students who belonged to Nes Ziyonah.[10]

Nes Ziyonah had sprung up without the knowledge of the elder dean of the Yeshivah, Rabbi Naftali Tsevi Yehudah Berlin (NeTsIV). In fact, according to Israel Kausner, who wrote a history of Nes Ziyonah, the members of the secret society prided themselves that they had been able to prevail upon Rabbi Berlin to join the greater Hovevei Zion movement and to assume a role of leadership alongside Rabbis Samuel Mohilever and Mordechai Eliasberg of Bausk.[11] In 1890, somehow Nes Ziyonah came to the attention of the Russian government authorities. One of its leaders (Yosef Rothstein) was arrested but subsequently released. When Rabbi Berlin learned that such a society had sprung up in the Yeshivah under his very nose, he was aghast. He feared that Nes Ziyonah might jeopardize the existence of the Yeshivah, which was under constant government scrutiny.[12] Leaving aside pragmatic considerations, in principle, Volozhin had always been a bastion of pure Torah learning; there was no room in it for Zionist activism.[13] Nes Ziyonah ceased to exist. (Hovevei Zion, with its office in Odessa, was legalized by the Tsarist government in 1890.)[14]

The idealistic young men who had formed Nes Ziyonah were not ones to easily give up. Nes Ziyonah morphed into Netsah Yisrael, whose express goal was to advocate on behalf of Zionism and religion. (Nes Ziyonah had restricted its activities to settling the Land of Israel.) Most prominent in this reincarnation of Netsah Yisrael was—Yehudah Leib Don Yahya.[15]

It is against this backdrop—the publicistic activity of Netsah Yisrael—that one must view Don Yahya’s tract, Zionism from the Viewpoint of Religion.

Let us briefly sum up some of the more salient points of the booklet.

Don Yahya begins by clarifying that the return of the nation to its land can in no way be viewed as the complete redemption prophesied in Scripture. The prophets’ vision, while including the ingathering of exiles, extends beyond that to global mankind’s acknowledging God and embracing His Torah.[16]

On the other hand, Don Yahya is flummoxed by various rabbis who adopt an all-or-nothing attitude to the Zionist organization’s striving to secure from the Ottomans a safe haven for Jews in the Holy Land. Just because the Zionist dream does not encompass the comprehensive vision of our prophets of old, is no reason to reject Zionism. Granted that the Zionist goals are much more modest in scope; that still does not justify opposing the movement. Don Yahya’s own reading of the sources—Biblical and Rabbinic—is gradualist. He anticipates a phased redemption. The Jews’ return to the Land is certainly the beginning, the first installment in a protracted process which will eventually—upon completion of “the full and encompassing redemption” (“ha-ge’ulah ha-sheleimah ve-ha-kelalit”)—culminate in the restoration of the Davidic dynasty in the person of King Messiah and the rebuilding of the Temple.[17]

The author adopts as his paradigm the Second Temple period. Taking issue with those who construe the return from Babylonian captivity as a “temporary remembrance” (“pekidah li-zeman mugbal”), Don Yahya maintains that the Second Commonwealth had the potential to develop into full-blown redemption. With that model in mind, he writes that return from exile and settling the Land can evolve beyond that to greater spiritual dimensions.[18]

After having made his case for the compatibility of the nascent Zionist movement and Judaism, Don Yahya tackles the painful question why some of the great Torah geniuses oppose Zionism.[19]

Don Yahya has a couple of explanations. First, knowledge of Torah is divided into Halakhah and pilpul, on the one hand, and matters of belief and opinion, on the other. Contemporary ge’onim (unlike their medieval predecessors Maimonides and Nahmanides) have devoted their lives to Halakhah, to the exclusion of emunot ve-de‘ot (beliefs and opinions). “In regard to the portion of Torah which is beliefs and opinions, their view does not exceed the view of an average Jew.”[20]

Rather conveniently, Don Yahya holds up as examples of recent Torah authorities who plumbed the depths of the beliefs contained in the Aggadah, and who concluded that the redemption shall begin with the Jews receiving permission to settle the Land of Israel—Rabbis Naftali Tsevi Yehudah Berlin and Mordechai Eliasberg—two rabbis who stood at the helm of Hovevei Zion.[21]

A second reason for the opposition of some ge’onim to Zionism is that they have been fed misinformation (or disinformation) by those of lesser stature who surround them. As the great men eschew reading newspapers, they must rely for information on extremists (kana’im) who skew their perception. They are told that the leaders of the Zionist movement are men who are not simply unobservant in their private lives, but furthermore, intent on uprooting Judaism.[22]

According to Don Yahya, the Zionist leaders profess no proficiency in matters of religion and are amenable to working with the great rabbis in matters pertaining to religion. He cites the example of a responsum from one of the great halakhic decisors of the generation to accommodate the Colonial Bank so that the prohibition of charging interest (ribit) be not transgressed. Don Yahya personally witnessed both the question from Zionist officialdom and the responsum issued by the elderly ga’on.[23] (Undoubtedly, “the elderly ga’on” [“ha-ga’on ha-yashish”] was Don Yahya’s own father-in-law, Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen, the dayyan or chief justice of Vilna.)[24]

Don Yahya points out the democratic character of the Zionist congresses. If more religious Jews would join the ranks of the Zionist movement, they would be able to turn the tide and steer the movement in a more religious direction.[25]

The author chides those religious elements opposed to Zionism not to gloat and say, “We told you so.” In the event that Zionism deviates from Judaism, this will be a self-fulfilling prophecy of doom; the anti-Zionist agitators will then be held responsible for bringing about that outcome by instructing observant Jews to stay clear of the movement.[26]

II.

As stated above, the Milu’im or Excursus of the pamphlet is a harshly worded rejoinder to the Rebbe of Lubavitch, Rabbi Shalom Dov Baer Schneersohn (1860-1920), who had made public his vehement opposition to Zionism on religious grounds.[27]

Again, one asks: How is possible that a staunch Habad Hasid such as Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya appended such an excursus to his work? From a remove of more than a century this seems inconceivable.

We need once more to place this pamphlet within the context of the times. Today, Habad has assumed a monolithic character, but at the turn of the twentieth century there existed a great divide between two competing “courts” within Habad Hasidism: Kopyst and Lubavitch. When Rabbi Menahem Mendel Schneersohn of Lubavitch (author of the responsa Tsemah Tsedek) passed in 1866, a dispute erupted over succession to the throne. The youngest son, Shmuel (Maharash), remained in Lubavitch and inherited control of that city. An older son, Yehudah Leib (Maharil), moved to the city of Kopyst, taking some of the Hasidim with him.[28] When within a year of the Tsemah Tsedek’s passing, Yehudah Leib passed, his son Shelomo Zalman (author of the Hasidic work Magen Avot) became the Kopyster Rebbe. And when in 1900 the Kopyster Rebbe passed, he was succeeded by his younger brother Rabbi Shemaryah Noah Schneerson (author of the Hasidic work Shemen la-Ma’or). Though there was a brief attempt on the part of Rabbi Shemaryah Noah Schneerson to establish himself in the city of Kopyst, eventually he returned to his rabbinate in Bobroisk, which then became the center of this branch of Habad Hasidism.[29] With the passing of the Rebbe of Bobroisk in 1923, this branch ceased to exist, leaving only the Lubavitch faction. At that point, remnants of the Bobroisker Hasidim transferred their allegiance to the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

In the early years of the twentieth century there erupted a major financial dispute between Bobroisk and Lubavitch regarding control of the purse strings of Kollel Habad in Erets Yisrael. (One may find evidence of the dispute in letters of Rav Kook from this period, when as Rabbi of Jaffa he offered guidance how to come to a compromise.)[30] The tension arose because each Rebbe wanted his representative in Erets Yisrael to be responsible for disbursement of the funds raised by the Hasidim in Russia for the support of their brethren in the Holy Land.

Thus, there are historians who would explain the tension between Bobroisk and Lubavitch as being purely financial.[31] Truth be known, there were ideological issues dividing the two cousins, Rabbi Shemariah Noah of Bobroisk and Rabbi Shalom Dov Baer of Lubavitch. In general, it may be said that the Bobroisker was more progressive, more forward-looking. The Lubavitcher was more old-school, more conservative in outlook. These different Weltanschauungen found expression on many fronts.

When the Russian government sought to demand of the rabbis proficiency in the Russian language, the Bobroisker (as Rabbi Meir Simhah Cohen of Dvinsk) found this a reasonable demand; the Lubavitcher (as Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik of Brisk and Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan [a.k.a. Hafets Hayyim]) fought against this proposal tooth and nail.[32]

When it came to deciding which city should serve as the center of Habad Hasidism in Erets Yisrael—Hebron or Jerusalem—Rabbi Shalom Dov Baer militated to retain the center in the provincial town of Hebron rather than allow the center to shift to Jerusalem.[33] In this way, the Lubavitcher Rebbe believed he could shield the Hasidim from the distractions of urban civilization. The Bobroisker did not think it realistic to keep the Hasidim “down on the farm.” Willy-nilly, establishment of a lending library in Hebron would bring secular literature to the curious eyes of Hasidic youth.[34]

And finally, we arrive at the issue with which we began: Zionism. While Lubavitch would have no truck with Zionism, out of the “Kibbutz” (study-hall for advanced rabbinic students) of Bobroisk there would emerge prominent rabbis of the Mizrahi or Religious Zionist movement.[35]

The answer to the question how Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya, a fervent Habad Hasid, could oppose the Rebbe of Lubavitch is simple: Don Yahya was a Kopyster Hasid,[36] not a Lubavitcher Hasid.

Epitaph on Tombstone of Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya in Ludza (Lutzin)

צנא מלא ספרא

כלו ספרא מבעל —-

מגזע רבני —-

מחבר אבן שתיה

הרב הגאון ר’ אליעזר

בהרב ר’ שבתי

דון יחייא

ויאסף אל עמיו

ד’ ימים לחדש תמוז

שנת תרפו

[1] Yehudah Leib Don Yahya was born in Drissa (today Verkhnyadzvinsk, Belarus) in 1869 and passed in Tel-Aviv in 1941. Besides this Zionist manifesto, Rabbi Don Yahya published two volumes of Halakha and essays and sermons: Bikkurei Yehudah, vol. 1 (Lutzin, 1930); vol. 2 (Tel-Aviv, 1939).

Volume One of Bikkurei Yehudah was published in Lutzin (Ludza) by the author’s cousin, Rabbi Benzion Don Yahya, Rabbi of Lutzin. At that time Rabbi Yehudah Leib served as Rabbi of Chernigov, Soviet Russia. In his preface to the work, Benzion Don Yahya explains that the manuscript was sent to him for publication because there is no longer a Hebrew press in Russia. On pages 36-38, the Editor traces the lineage of the Don Yahya family. We learn that his paternal grandfather was Rabbi Shabtai Don Yahya, Rabbi of Drissa for sixty years until his death at approximately age 90 in 1907. One of Rabbi Shabtai’s sons, Rabbi Eliezer, became Rabbi of Lutzin (Ludza), a rabbinate inherited by his son, the Editor (Rabbi Benzion). In 1840, there were born to Rabbi Shabtai twins: Menahem Mendel and Hayyim. Menahem Mendel served as Rabbi of Kopyst for some years, passing there in 1920. Hayyim served as Rabbi of Shklov, and after his father Shabtai’s passing, as Rabbi of Drissa, until his own passing in 1913. Hayyim’s son, Yehudah Leib, served as Rabbi in Shklov and Vietka, until he inherited from his father the Rabbinate of Drissa in 1913. (In Bikkurei Yehudah, vol. 2, f. 159, there is a letter dated 5673 [i.e. 1913] from Rabbi Meir Simhah of Dvinsk to Rabbi Don Yahya congratulating him on assuming the rabbinate of his father and grandfather in Drissa.) In 1925, Yehudah Leib was accepted as Rabbi of Chernigov.

In Shklov, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya ministered to the “Kehal Hasidim” (exclusive of the Mitnagdim, who would have had their own Rav). (See below note 4.) However, it should be mentioned that the communities of Vietka and Chernigov as well figure prominently in the annals of Habad Hasidism.

The Rabbi of Vietka, Rabbi Dov Baer Lifshitz, author of an important commentary on Tractate Mikva’ot, Golot ‘Iliyot (Warsaw, 1887), refers to Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi as “dodi zekeini” (“my great uncle”). See ibid., Addendum to Introduction, and 7c.

The man who immediately preceded Rabbi Don Yahya as Rabbi of Chernigov, Rabbi David Tsevi (Hirsch) Hen (referred to by the Hasidim as “RaDaTs”) was acknowledged as one of the greatest of Habad Halakhists in his day. In 1925, through the intervention of Chief Rabbi Kook, he was able to emigrate from the Soviet Union to Erets Yisrael together with his daughter Rahel, son-in-law Rabbi Shalom Shelomo Schneerson (brother of Rabbi Levi Isaac Schneerson, Rabbi of Yekaterinaslav, today Dnieperpetrovsk, and uncle of Rabbi Menahem Mendel Schneerson, Lubavitcher Rebbe of Brooklyn), and granddaughter Zelda, who would later achieve fame as a Hebrew poet. See Igrot Re’iyah, vol. 4 (Jerusalem, 1984), Letter 1330 (p. 251), in which Rav Kook attempts to install the recently arrived Rabbi S.S. Schneerson as Rav of Haderah. Rav Kook’s involvement in bringing RaDaTs and family to Erets Israel is discussed in the recently published annals of the Hen Family, Avnei Hen, ed. Eliezer Laine and S.Z. Berger (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot, 2015).

Reviewing the second volume of Bikkurei Yehudah, Rabbi Zevin wrote an especially insightful appreciation of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya. Rabbi Zevin, himself a Habad Hasid, noted how rare it was to find in the twentieth century a Habad Hasid who combined both persona of the maskil (intellectual) and the ‘oved (master of contemplative prayer). (In the latter connection, Rabbi Zevin observed that Rabbi Don Yahya wore daily three pairs of tefillin: Rashi, Rabbenu Tam, and Shimusha Rabbah.) Beyond Habad Hasidism, Don Yahya mastered Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik’s method of Talmudic analysis and the process of pesikah (Halakhic decision) of Don Yahya’s father-in-law, Rabbi Shleimeleh Hakohen, the Dayyan of Vilna. See Rabbi Shelomo Yosef Zevin, Soferim u-Sefarim (Tel-Aviv: Abraham Ziyoni, 1959), pp. 296-300.

It is noteworthy that the volume contains a responsum to Rabbi Mordechai Shmuel Kroll, the Rav of Kefar Hasidim in Erets Yisrael, and a Halakhic novella of Rabbi Kroll. See Bikkurei Yehudah, vol. 2, ff. 121-129, 160-162. Rabbi Kroll was the eminent disciple of Rabbi Don Yahya.

[2] Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik’s opposition to Zionism is well known. One particular statement should illustrate how extreme was Rabbi Hayyim’s opposition to the new movement. The following incident took place in Minsk in 1915 (when many Jews were forced to flee their homes before the German invasion and seek refuge in the large city located farther east).

Young Raphael Zalman Levine was walking down the street with his father, Rabbi Abraham Dov Baer Levine (known as the “Mal’akh,” the “Angel”). Pinned to the adolescent’s lapel was an insignia of the Keren Kayemet le-Yisrael (Jewish National Fund), to which he had recently donated. The elder Levine was adamantly opposed to the Zionist enterprise and demanded that his son remove the pin, which he found offensive. Father and son were in the midst of an intense argument when, lo and behold, they saw approaching them from the opposite direction none other than the great Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik.

Rabbi Levine said to Rabbi Soloveitchik: “My son wants to ask you a she’elah (question).”

Rabbi Soloveitchik turned to Raphael Zalman: “You can ask your father.” (Rabbi Levine and Rabbi Soloveitchik were friends.)

Rabbi Levine persisted: “My son wants to ask you a she’elah in emunah (a matter of faith).”

“Emunah?” Rabbi Soloveitchik’s face now assumed a serious expression.

Young Raphael Zalman was put on the spot and forced to ask Rabbi Hayyim what he thought of his donation to the Jewish National Fund.

It just so happened that across the street was a church.

Rabbi Hayyim responded to his young questioner: “If you have a few spare kopecks in your pocket, you can place them there rather than in the pushke of the Keren Kayemes.”

(Reported by RYYL and by Prof. Richard Sugarman who both heard this anecdote from the mouth of Rabbi Raphael Zalman Levine of Albany, New York, on two separate occasions.)

The episode is also reported in Rabbi Raphael Zalman Levine’s name in Rabbi C.S. Glickman, Mi-Pihem u-mi-Pi Ketavam (Brooklyn, NY, 2008), pp. 119-120.

Though the sharpness of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik’s statement is shocking, Halakhic opposition to donating to the Zionist cause was shared by several East European rabbinic leaders. A decade later in 1925, four distinguished leaders of Polish Jewry, the Hasidic Rebbes of Gur, Ostrovtsa, Radzyn, and Novominsk, addressed a letter to Rav Kook adjuring him to curtail his support of Keren Kayemet le-Yisrael and Keren ha-Yesod. See Igrot la-Rayah, ed. B.Z. Shapiro (Jerusalem, 1990), Letter 199 (pp. 303-304); facsimile on p. 590.

Rav Kook, unlike the Polish Rebbes, differentiated between the two funds, lending his support to Keren Kayemet le-Yisrael, which directed funds to the physical reclamation of the land, but not to Keren ha-Yesod, which funded secular (and perhaps anti-religious) culture. See Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook, Li-Sheloshah be-Ellul, vol. 1 (1938), par. 44 (p. 22); Igrot ha-Rayah, vol. 5: 5682, ed. Ze’ev Neuman (Jerusalem, 2019), pp. 407-413.

[3] According to his namesake and great-grandson, journalist Shabtai Don Yahya (who wrote under the pen name of “Sh. Daniel”), the Rabbi of Drissa was known in Lubavitch as “Reb Shebsel Drisser.” Sh. Don Yahya wrote that it was said that the Rabbi of Drissa might have become one of the great men of the generation in terms of Talmudic learning, but his Hasidic exuberance stunted his academic growth. See Shabtai Don Yahya, Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya (Jerusalem, 1932), pp. 10-11.

(The title-page makes the point that the book bears the encomium of Chief Rabbi Kook. Shabtai Don Yahya was one of the first students of Merkaz Harav and a devoted disciple of Rav Kook. Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya is a biography of the author’s paternal grandfather, the Rabbi of Lutzin, son of Rabbi Shabtai Don Yahya. As a youth, Avraham Yitshak Hakohen Kook studied under Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya in Lutzin. Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya was born 4 Tammuz 5598 [i.e. 1838] and passed on his birthday, 4 Tammuz 5686 [i.e. 1926]. See the epitaph on his tombstone at the conclusion of this article. A photograph of the funeral of Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya in Lutzin in 1926 may be found in Rabbi Yitzhak Zilber’s autobiography, To Remain a Jew. Zilber’s original surname was “Ziyoni.” Rabbi Eliezer Don Yahya inherited the rabbinate of Lutzin from his illustrious father-in-law Rabbi Aharon Zelig Ziyoni.)

Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya often quotes the Tsemah Tsedek in his Halakhic responsa.

[4] In the biography of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Don Yahya in Shmuel Noah Gottlieb’s Ohalei Shem (Pinsk, 1912), p. 207, s.v. Shklov, it states that Don Yahya assumed the rabbinate of Shklov in 1906. However, as early as Friday, 17 Menahem Av [5]664,” i.e. 1904, Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen addressed his son-in-law as “Rav Av-Beit-Din of the congregation of Hasidim of Shklov.” See Bikkurei Yehudah, vol. 2 (Tel-Aviv, 1939), 145a.

In Shklover Yidden (1929) and Feter Zhoma (1930), the Yiddish and Hebrew poet and writer Zalman Shneur portrayed the Hasidim of his birthplace.

Earlier, Rabbi Yehudah Leib’s father, Rabbi Hayyim Don Yahya, had served as Rabbi of Shklov. A halakhic responsum of Rabbi Hayyim Don Yahya (datelined “5653 [i.e. 1893], Shklov”) was published in the journal of the Skvere Kollel, Zera‘ Ya‘akov 26 (Shevat 5766 [i.e. 2006]), pp. 17-21. On p. 20, Rabbi Hayyim mentions the learned opinion of his brother from Kopyst [i.e. Rabbi Menahem Mendel Don Yahya].

[5] Rabbi Yitshak Lichtenstein writes in the introduction to the volume that there were many such Tagbikher that were lost to posterity. This particular journal was inherited by Rabbi Hayyim’s son, Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik. (Behind the scenes, the Tagbuch was made available to Rabbi Lichtenstein by his maternal uncle, Prof. Haym Soloveitchik of Riverdale, son of Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik of Boston, son of Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik.)

[6] See Bikkurei Yehudah, vol. 2 (Tel-Aviv, 1939), 142a-144b. The volume was edited by the author’s son-in-law Rabbi Yitshak Neiman. Rabbi Zevin explains that though the volume was submitted for publication in 1939, it was not issued until 1941, a few weeks before the author’s passing. See S.Y. Zevin, Soferim u-Sefarim (Tel-Aviv: Abraham Ziyoni, 1959), p. 297. The two novellae of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik (to Bava Kama 13a and Ketubot 21a) were reprinted in the memorial volume for Rabbi Neiman, Zikhron Yitshak (Jerusalem, 1999), along with several novellae of his father-in-law, Rabbi Don Yahya.

[7] See Israel Klausner, Toledot “Nes Ziyonah” be-Volozhin (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1954), pp. 25, 65, 113. Moshe Mordechai Epstein appears in a group photo on p. 26.

[8] Ibid. p. 24.

[9] Rabbis Epstein and Meltzer would eventually become brothers-in-law by their marriage to two sisters, daughters of the Maecenas Shraga Feivel Frank of Kovno.

[10] Heard from Rabbi Yosef Soloveichik of Jerusalem (son of Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik of Chicago), a great-grandson of Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik. Rabbi Yosef Soloveichik explained the exact halakhic reasoning whereby his ancestor was able to release young Isser Zalman Meltzer from his solemn oath.

This Soloveichik family tradition, which reflects Rabbi Hayyim’s disapproval of Nes Ziyonah, seems to fly in the face of Yosef Rothstein’s memoir, whereby Rabbi Hayyim rejoiced at Rothstein’s release after he had been arrested by the Russian police:

Also the Gaon Rabbi Hayyim of Brisk, of blessed memory, greatly rejoiced over me. He received me with joy and brought me before the NeTsIV, of blessed memory, who was pleased by my return, though he did say to me that this is not the place [for activism]. “A mitsvah that can be performed by others, we do not cancel for it the study of Torah” [MT, Hil. Talmud Torah 3:4]…Evidently, the NeTsIV too was content but had to act as if he disapproved…

(Yosef Rothstein, in Israel Klausner, Toledot “Nes Ziyonah” be-Volozhin, p. 123)

See earlier on p. 13 the NeTsIV’s opposition to students taking time out from their Torah study for activism—even on behalf of a cause as dear to NeTsIV’s heart as Yishuv Erets Yisrael.

[11] Ibid. p. 14.

[12] Ibid. p. 19.

[13] See above note 10.

[14] Klausner, Toledot “Nes Ziyonah” be-Volozhin, p. 21.

[15] Ibid. pp. 22-24. The members of Netsah Yisrael were also sworn to secrecy. Netsah Yisrael lasted until the closing of the Volozhin Yeshivah by the Russian authorities in 1892.

[16] Ha-Tsiyoniyut mi-nekudat hashkafat ha-dat, pp. 5-6.

[17] Ibid. pp. 6-7.

[18] Ibid. pp. 7-10.

[19] Ibid. p. 15.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid. p. 16.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid. pp. 16-17. Don Yahya does not go into Halakhic details. Usually, the way to circumvent the problem of ribit (interest) is by drafting a “heter ‘iska.” Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook relates that when the Zionist Colonial Bank was founded, his father, Rabbi Avraham Yitshak Hakohen Kook, entered into negotiations with the Zionist officials and rabbis, which resulted in a “shtar heter ‘iska.” See Rabbi Tsevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook, Li-Sheloshah be-Ellul, vol. 1 (1938), par. 17 (pp. 11-12).

[24] The elderly Dayyan of Vilna, Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen (author of Heshek Shelomo) was exceptionally respectful of Theodor Herzl when the latter visited Vilna, extending to him the priestly benediction at a reception in Herzl’s honor. See Israel Cohen, History of Jews in Vilna (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1943), p. 350; and Israel Klausner, Vilna: “Jerusalem of Vilna,” 1881-1939, vol. 2 (Hebrew) (Israel: Ghetto Fighters’ House, 1983), p. 339.

Another son-in-law of Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen, Rabbi Nahum Greenhaus of Trok (Lithuanian, Trakai), a suburb of Vilna, was, like Don Yahya, an outspoken advocate of Zionism. Because of their support of the movement, both Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen and Rabbi Nahum Greenhaus suffered persecution by anti-Zionist elements in Lithuanian Jewry. See Klausner, ibid. pp. 330-333.

Rabbi Nahum Greenhaus’ namesake was Rabbi Nahum Partzovitz (known in his youth as “Nahum Troker”), who would one day become the illustrious Rosh Yeshivah of the Mirrer Yeshiva in Jerusalem. Rabbi Nahum Partzovitz’s father, Rabbi Aryeh Tsevi Partzovitz, inherited the rabbinate of Trok from his father-in-law, Rabbi Nahum Greenhaus.

A third son-in-law of Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen of Vilna was Rabbi Meir Karelitz, older brother of Rabbi Abraham Isaiah Karelitz (author of Hazon Ish), who was prominent in Agudah circles, both in Vilna and later in Erets Yisrael.

[25] Ha-Tsiyoniyut mi-nekudat hashkafat ha-dat, p. 17.

[26] Ibid.

This modern disagreement sounds vaguely reminiscent of the disagreement between Resh Lakish and Rabbi Yohanan in Talmud Bavli, Yoma 9b-10a. Resh Lakish said of Babylonian Jewry: “God hates you. If you had gone up to the Land of Israel en masse in the days of Ezra, the divine presence would have rested in the Second Temple and there would have been a resumption of full-blown prophecy. Now that you have gone up in pitifully small numbers (dalei dalot), but a remnant of prophecy remains, the bat kol (heavenly voice).” Rabbi Yohanan responded: “Even if all of Babylonian Jewry would have gone up to the Land in the days of Ezra, the divine presence would not have rested in the Second Temple, for it is written: ‘God will broaden Japheth and dwell in the tents of Shem’ [Genesis 9:27]. Though God will broaden Japheth, the divine presence rests only in the tents of Shem.” Rashi explains that the divine presence was prevented from resting in the Second Temple because it was built by the Persians; the divine presence rested only in the First Temple which was built by Solomon of the seed of Shem.

Evidently, Rabbi Don Yahya (like Resh Lakish) was convinced that that what was crucial to effecting a spiritual revolution in Erets Yisrael was a critical mass. His opponents (like Rabbi Yohanan) could not be swayed that it was merely a matter of numbers. To their thinking, non-Jewish influence at the very inception of the Zionist movement would preclude it from bringing about the hoped for spiritual renascence so woefully lacking in the Jewish collective.

[27] See ’Or la-Yesharim (Warsaw, 1900), pp. 57-61. For other (later) recordings of Rabbi Shalom Baer Schneersohn’s anti-Zionist stance, see Bezalel Naor, When God Becomes History: Historical Essays of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook (New York, NY: Kodesh Press, 2016), p. 168, n. 10.

[28] In his autobiography, Chaim Tchernowitz (“Rav Tsa‘ir”) revealed some of the intrigue in the aftermath of the Tsemah Tsedek’s passing that led to the Kopyst-Lubavitch schism. See Ch. Tchernowitz, Pirkei Hayyim (New York, 1954), pp. 104-106.

[29] See Hayyim Meir Heilman, Beit Rabbi (Berdichev, 1902), vol. 3, chap. 9.

[30] See Igrot ha-Rayah, vol. 1 (1962), Letter 39 (pp. 34-36), to Rav Kook’s maternal uncle, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Felman of Riga, a Kopyster Hasid. The letter is datelined, “Jaffa, 3 Marheshvan, [5]667,” i.e. 1906.

[31] Roughly thirty years ago I heard this monetary explanation from Rabbi Chaim Liberman, who had served as personal secretary and librarian of Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn of Lubavitch.

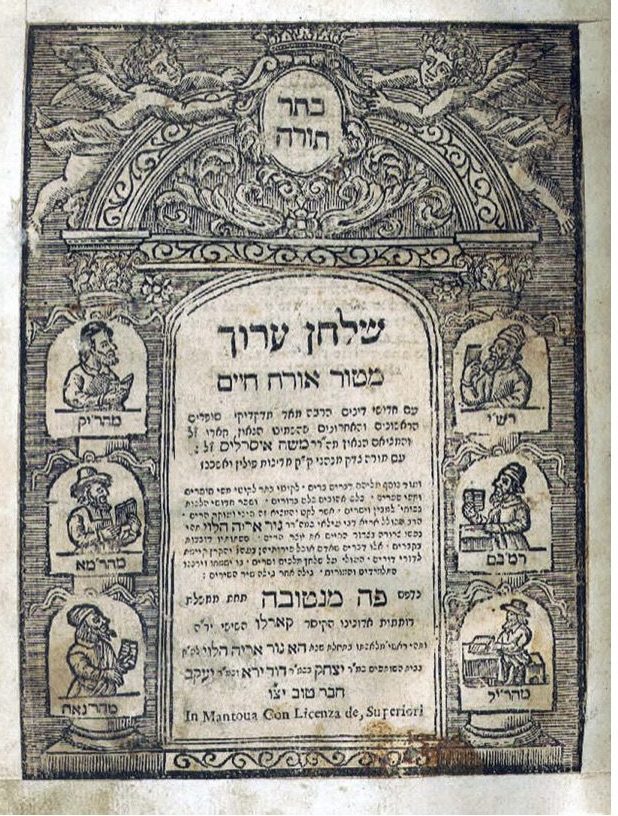

Interestingly enough, in the 1880s there emerged a theological dispute between the Rebbes of Kopyst and Lubavitch. The way it came about was in the following manner. After the passing of Rabbi Samuel (Maharash) of Lubavitch in 1882, his sons published an edition of their ancestor Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi’s Torah ’Or on the first three parshiyot or pericopes (Bereshit, Noah, Lekh Lekha). Entitled Likkutei Torah, it was brought out in Vilna in 1884. The publishers took the liberty of incorporating into the text comments of the recently deceased Rabbi Samuel Schneersohn. The Kopyster Rebbe, Rabbi Shelomo Zalman Schneerson (author of Magen Avot) was outraged and penned a public letter of protest.

One comment of his uncle Rabbi Samuel (to Parashat Noah) in particular provoked the Kopyster Rebbe, this touching on the proper way to understand Rabbi Isaac Luria’s metaphor of Tsimtsum. In three letters to Rabbi Dan Tumarkin of Roghatchov (a Lubavitcher Hasid), the Kopyster Rebbe clarified his position on Tsimtsum and how it differed from that of Rabbi Samuel Schneersohn. The correspondence is briefly alluded to in H.M. Heilman, Beit Rabbi, vol. 3, chap. 10, s.v. Rabbi Dan Tumarkin. The entire exchange is available in Rabbi Mordechai Menashe Laufer, Ha-Melekh bi-Mesibo, vol. 2 [Kfar Habad, 1993], pp. 283-293. (This truly fascinating correspondence was brought to my attention a generation ago by Baruch Thaler.)

Regarding the publication of Likkutei Torah (Vilna, 1884), see further Hayyim Meir Heilman, Beit Rabbi, vol. 1, 87a; vol. 3, 16a, 28a; Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine, “‘Likkutei Torah’ le-Shalosh Parshiyot,” Kfar Habad, nos. 931, 933. Available online at http://www.shturem.net/index.php?section=blog_new&article_id=29

[32] This issue was raised at the rabbinical conference held in St. Petersburg in 1910. The decisions reached by the delegates were relayed to Stolypin, Minister of the Interior. Some of the heated exchange between the Bobroisker and the Lubavitcher behind closed doors has been preserved in the memoirs of Isaac Schneersohn, one of the delegates to the conference; see I. Schneersohn, Leben un kamf fun Yiden in Tsarishen Rusland 1905-1917 (Paris, 1968). The chapters concerning the 1910 conference were translated from Yiddish into Hebrew by Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine, “Asifat ha-Rabbanim be-Rusya bi-Shenat ‘Atar,” Kfar Habad, no. 898. Availble online at: http://www.shturem.net/index.php?section=blog_new&article_id=24

According to Isaac Schneersohn, it was none other than he (Crown Rabbi of Chernigov) who proposed abolishing the position of Kazyonny Ravin (in Hebrew, “Rav mi-Ta‘am,” or Crown Rabbi), thus wresting authority from the secular-trained, modern “Rabbiner” and consolidating communal power in the hands of the Talmudically-trained traditional Rav—provided he be proficient in the Russian language.

[33] Historically, the Habad community in Hebron preceded that of Jerusalem. In 1823, Rabbi Dov Baer Shneuri of Lubavitch (“Mitteler Rebbe”), the second-generation leader of the Habad movement, founded a Habad community in Hebron. Later, in 1847, a group of Habad families from Hebron relocated to Jerusalem.

[34] See Kuntres me-Admo”r shelit”a mi-Bobroisk: Teshuvot nitshiyot va-amitiyot ‘al Kuntres Admo”r shelit”a de-Libavitz (1907).

[35] Two names come to mind: Rabbi Nissan Telushkin in the United States and Rabbi Shelomo Yosef Zevin in Erets Yisrael. Both studied in the “Kibbutz” of the Bobroisker Rebbe and received ordination from him. Eventually, with the extinction of Bobroisker Hasidism, both Telushkin and Zevin would transfer their allegiance to Lubavitch. However, their affiliation with the Religious Zionist movement could at times place them in an unenviable position. Particularly Rabbi Zevin oftentimes found himself between a rock and a hard place. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe residing in Brooklyn, would on occasion expect of Rabbi Zevin to promote positions at variance with his Mizrahi colleagues in Erets Yisrael (such as Chief Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog). See Marc B. Shapiro, Changing the Immutable: How Orthodox Judaism Rewrites Its History (Oxford: Littman, 2015), pp. 235; 238, n. 87.

A brief autobiographical sketch of Rabbi Telushkin (a native of Bobroisk) is found at the conclusion of his Halakhic work on mikva’ot (ritual baths), Tohorat Mayim (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot, 1990), pp. 355-356 (“Le-Zikaron”).

[36]In Rabbi Don Yahya’s letter to Rabbi Shelomo Yosef Zevin concerning the counterintuitive thought process that informed Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik’s Halakhic decisions, Rabbi Don Yahya refers to himself as a “Hasid [of] Kopyst.” The context is Rabbi Hayyim’s desire to procure a “Yanover esrog” (citron from Genoa, Italy) to fulfill the commandment, in compliance with the tradition of Habad, and earlier the Hatam Sofer, Orah Hayyim, no. 207. See Hiddushei ha-GRaH he-Hadash ‘al ha-Shas (B’nei Berak: Mishor, 2008), p. 586.

However, in Zikhron Yitshak (Memorial Volume for Rabbi Yitshak Neiman) (Jerusalem, 1999), p. 141 (which is the source of Hiddushei ha-GRaH), Rabbi Don Yahya refers to himself as a “Hasid (Habad).” It would be interesting to see the original of the letter, which may yet be in the hands of the heirs of Rabbi Zevin. From the fact that the word “Habad” is placed in parentheses, one is inclined to assume that this is an addition on the part of an editor (Rabbi Zevin?). According to the Introduction (“Petah Davar”) to Zikhron Yitshak, this is the first publication of the letter from Rabbi Don Yahya to Rabbi Zevin.

Klausner, Toledot “Nes Ziyonah” be-Volozhin, p. 17, records that in 1889, the members of Nes Ziyonah were able to elicit letters of support for the conception of Yishuv Erets Yisrael from the Hasidic Rebbes of Kopyst and Bohush (a branch of Ruzhin).

Finally, for a discussion regarding lot 93, Menukha ve-Kedusha and censorship see our post

Finally, for a discussion regarding lot 93, Menukha ve-Kedusha and censorship see our post