The Enigma of Abraham Rosenberg, R. Yitzchak Scheiner, Mordecai Kaplan, and Prof. Marvin Fox

Marc B. Shapiro

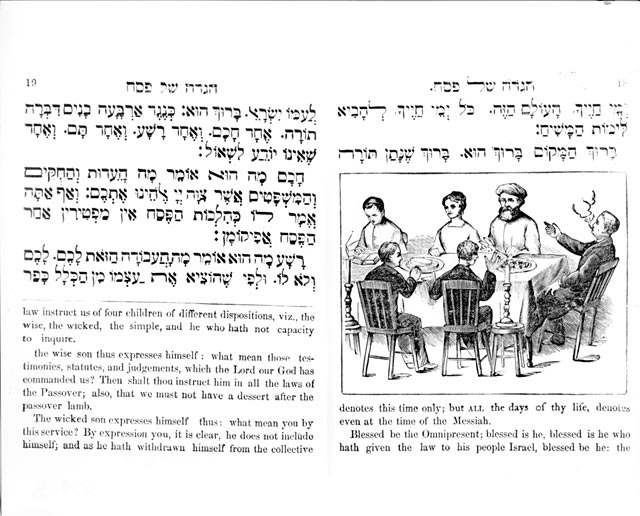

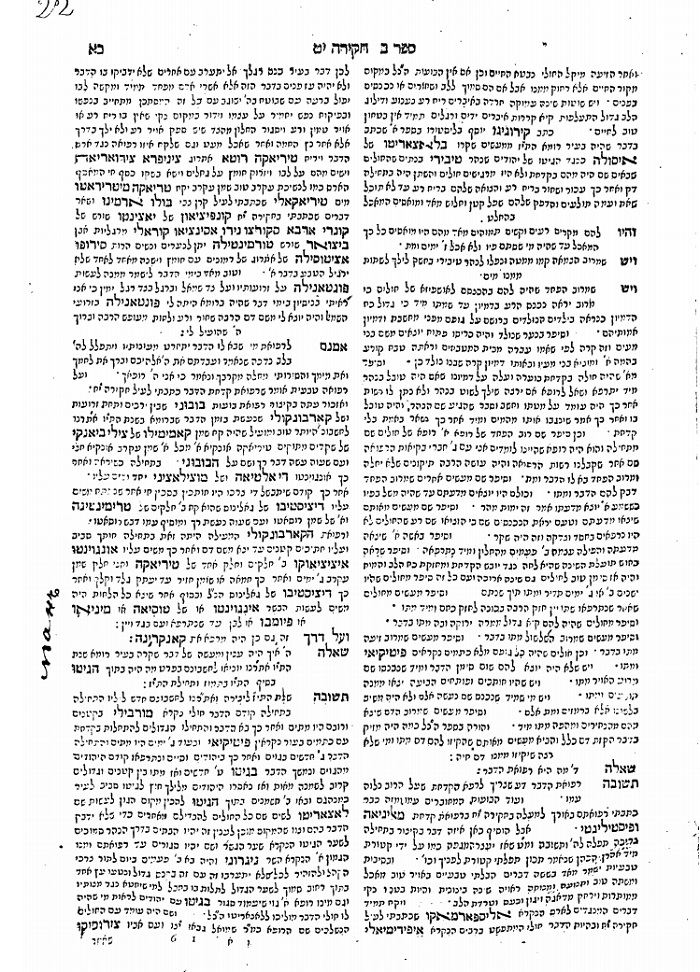

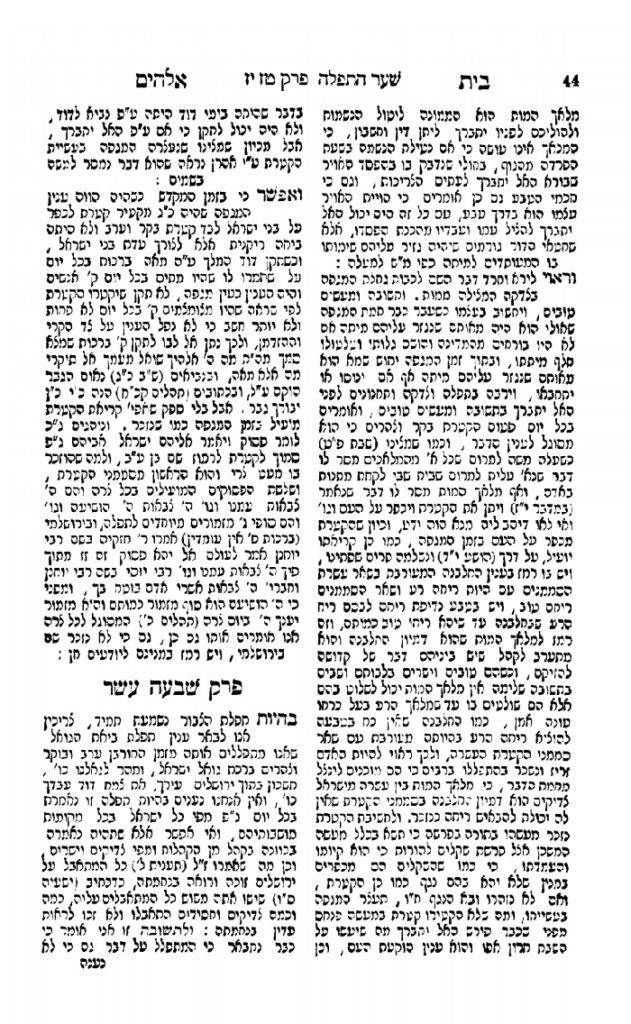

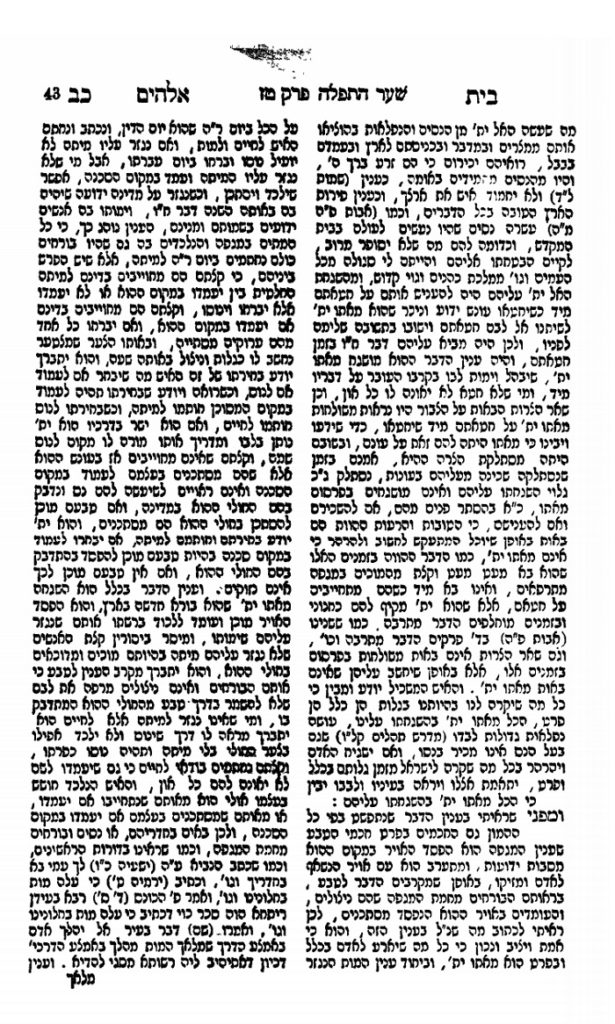

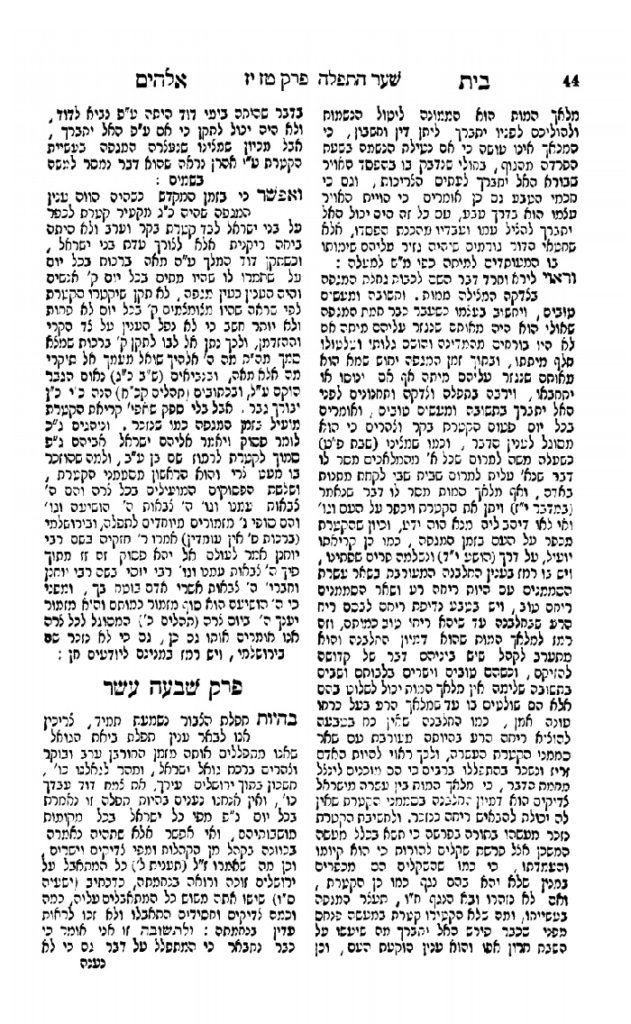

Abraham Rosenberg made his first appearance during the dispute over Solomon Friedlaender’s forged Yerushalmi Kodashim. He portrayed himself as a student of Friedlaender. Here is the title page of his booklet Aneh Khesil in which he defends Friedlaender from the attacks of his critics.

Rosenberg also wrote some other things in defense of Friedlaender, including an article in the Frankfurt Orthodox paper Der Israelit and letters to various figures who were involved in the dispute over the Yerushalmi Kodashim.

Who was Rosenberg? Discussion of this will be found in R. Baruch Oberlander’s forthcoming book on the forged Yerushalmi Kodashim, a work which is sure to be a tour de force of scholarship. (The Hungarian version of the book has already appeared.) Based on what R. Oberlander documents, I don’t think there can be any doubt that Rosenberg was not a real person but was a creation of Friedlaender. Even the city that Rosenberg claimed to be rabbi of does not exist. In the meantime, for those who want to learn about this fascinating story, I recommend this video from R. Oberlander.

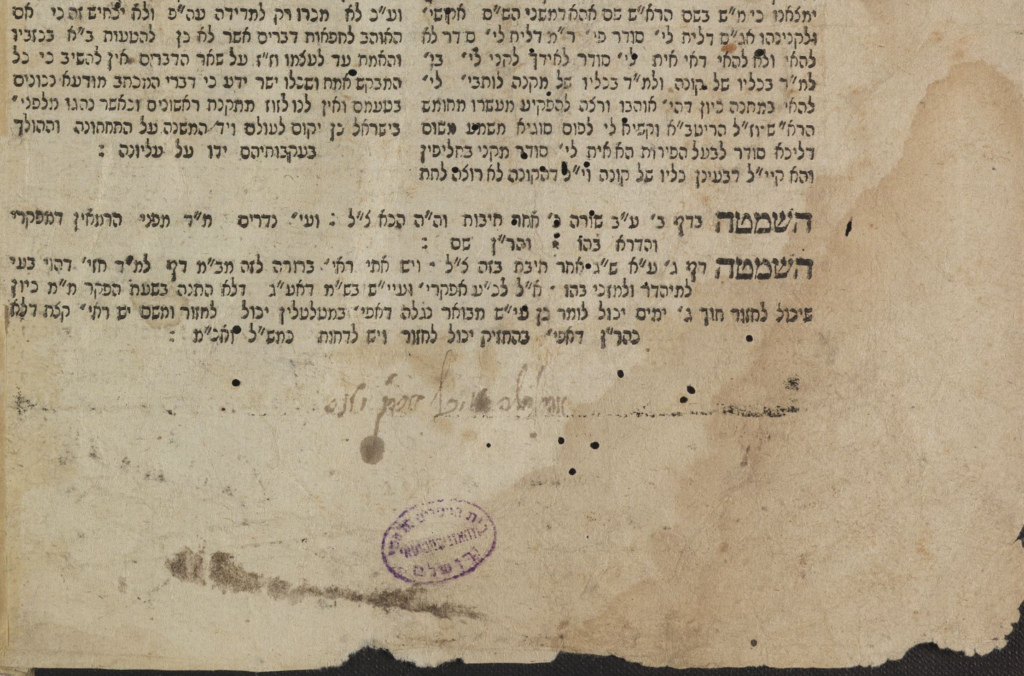

The story becomes even stranger, as beginning some fifteen years after Rosenberg’s first appearance in the Yerushalmi Kodashim controversy, a few articles written by an otherwise unknown “A. Rosenberg” appeared in 1923 and 1924. Friedlaender died in January 1924, so in theory it is possible to argue that he is the author of these articles that appeared in the Hebrew section of the German Orthodox journal Jeschurun.[1] Yet it is much more likely that the articles were written by someone else who took the pseudonym. Two of the articles in Jeschurun focus on the Jerusalem Talmud. The other article deals with how biblical verses are cited with variations in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, and Rosenberg argues against the notion that these quotations are evidence of biblical readings at variance with what is found in the so-called Masoretic text. In addition to these articles, Oberlander also refers to A. Rosenberg’s Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, which was published in Lodz, 1928 (so at least it says on the book’s title page). This is four years after Friedlaender’s death, so he could not have been the author.

If you look at Rosenberg’s book, you can’t help but be impressed that the author knows the Jerusalem Talmud and rishonim, and he is also on top of modern scholarship. At first glance, it seems that were very few people in the world at that time who were able to write such a work, which has led to speculation about who the author could be. Oberlander, in his forthcoming book, writes as follows:

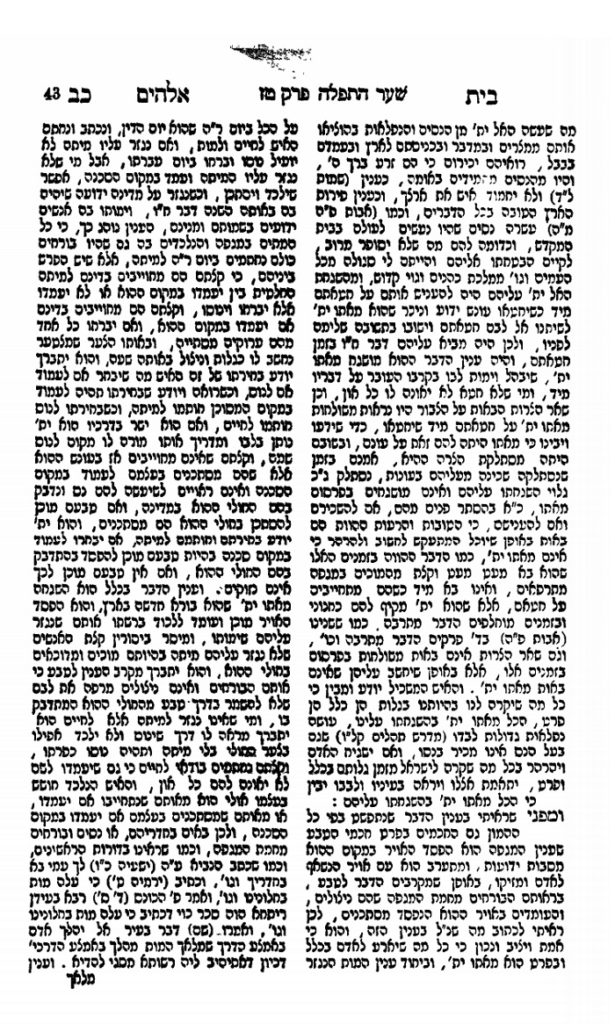

מהרב פרופ’ ש”ז הבלין שמעתי את ההשערה ש”א. רוזנברג” מירושלים אינו אלא פרופ’ שאול ליברמן (1898-1983), שידוע כמי שאהב מעשה קונדס כאלו (ראה גם י”ש שפיגל: ’עמודים בתולדות הספר העברי – בשערי הדפוס ‘עמ’ 46 הערה 151, 48 הערה 161). אמנם פרופ’ מלך (מרק) שפירא במכתבו אלי דוחה השערה זו, שהרי עד שנת 1928, כשהתחיל ללמוד באוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים, לא היה לו לליברמן שום ידע מדעי ולא השתמש בשיטות מדעיות בלימודים שלו. ראה Elijah J. Schochet and Solomon Spiro, Saul Lieberman – The Man and His Work, New York, 2005, p. 7-8

Oberlander cites Prof. Shlomo Zalman Havlin who speculates that A. Rosenberg is none other than Saul Lieberman. Indeed, a cursory examination of Rosenberg’s book shows great similarity with Lieberman’s works on the Yerushalmi and Tosefta. Yet when R. Oberlander asked me about this, I told him that Lieberman could not have written Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi. On p. 106 we see that the book, which shows great awareness of modern scholarship, was completed erev Yom Kippur 1926. Rosenberg’s articles in Jeschurun from a few years before also show an awareness of modern scholarship. Yet until Lieberman began studying at the Hebrew University in 1928, he had not been introduced to academic scholarship on the Talmud,[2] and he certainly was not writing anything about this in the early 1920s.

If Lieberman is the author of Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi we must assume that there are three A. Rosenbergs. 1. Friedlaender, 2. the author of the Jeschurun articles, 3. Lieberman. Even if Lieberman has nothing to do with the book, it is still possible that the author of Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi took the name “A. Rosenberg” in imitation of the earlier author in Jeschurun, but they are not the same person.

I asked Havlin what led him to conclude that Lieberman is the author. He replied by noting that we cannot learn anything from the name “A. Rosenberg”, and he added that even the year and place of publication (Lodz) are not certain. In other words, it is possible that the book actually appeared after 1928 and was published in Palestine.

Havlin noted a few other considerations that led him to his conclusion: The book appeared at the same general time as Lieberman’s Al ha-Yerushalmi (Jerusalem, 1929), the improbability of attributing such a work to anyone else during this period, Lieberman’s relationship with J.N. Epstein (see below), and that Lieberman had a mischievous streak that could have led him to publish the book anonymously. Havlin also noted that he heard the following from Prof. Yaakov Sussman. Sussman asked Lieberman about Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, and Lieberman responded: “Sheigetz, how did you come to this book?” By refusing to discuss the book with Sussman, or even to comment about who authored it, it is obvious that Lieberman was hiding something. Furthermore, I would add, isn’t it strange that Lieberman never refers to this book in any of his writings on the Yerushalmi? Here is a book with the exact sort of research that Lieberman was doing and yet he doesn’t mention it. דבר זה אומר דרשני.

Havlin also noted the following: On p. 19 n. 31 the author refers to a book of his in manuscript with the title המדע התלמודי וצרכיו. This is actually the title of a 1925 lecture delivered by J.N. Epstein upon assuming his position at the Hebrew University. The lecture was later published in Yediot ha-Makhon le-Madaei ha-Yahadut 2 (1925), pp. 5-22. Clearly the author was having some fun here, and we know that Lieberman had an interesting relationship with Epstein. Another personal comment is found on p. 91 where the author refers to R. Chaim Heller as “my friend”.

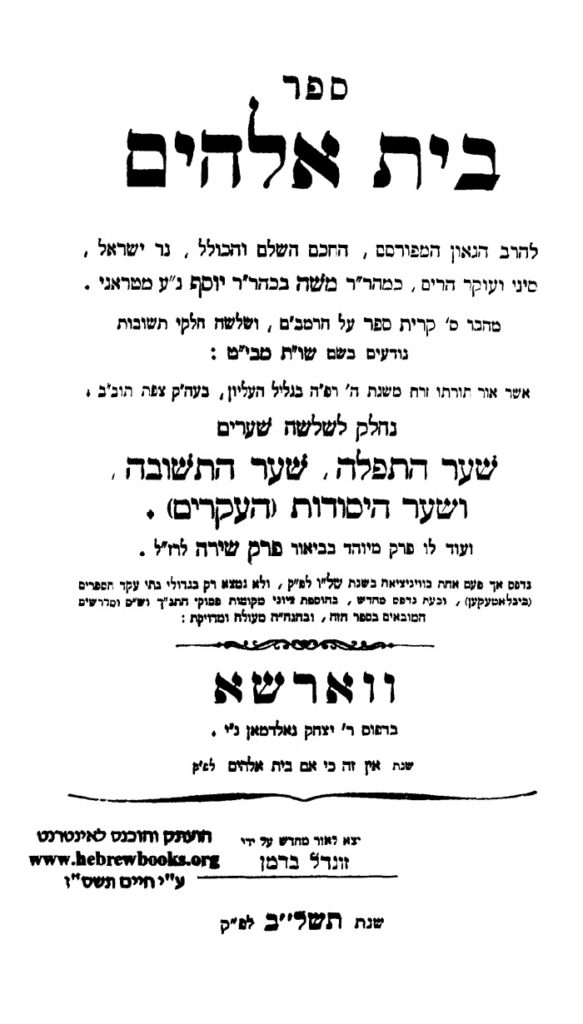

Returning to the quote above from R. Oberlander, he cites Yaakov Spiegel who gives two examples of Lieberman being a bit unconventional in some of his writings. In his book Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri: Be-Sha’arei ha-Defus,[3] Spiegel notes that in the preface to the 1970 publication of the first volume of R. David Pardo’s Hasdei David on Taharot, which was edited by Lieberman (as were the next two volumes on Taharot), Lieberman signs his name in the preface as .ש.ל. Spiegel adds:

יש אומרים שחתם את שמו בראשי תיבות ולא בשמו המלא, מפני שרצה שהספר יכנס לבית המדרש, והמבין יבין

Yet this is incorrect, as Lieberman always ended the prefaces to his books with his initials. We see this beginning with his first book, Al ha-Yerushalmi, published in Jerusalem, 1929, long before he ever thought of joining the JTS faculty.

So his use of initials has nothing to do with covering up who he was, and on the very first page of the preface to Hasdei David he refers to what he wrote in Tosefta ki-Feshutah. However, it is noteworthy that Lieberman’s name does not appear on the title page of the book as you can see here.

This, perhaps, was due to a desire to have the book accepted in yeshivot. It is one thing to have references to Tosefta ki-Feshutah inside the book, and something else entirely to have Lieberman’s name on the title page, which might have prevented yeshivot from purchasing Hasdei David.

Spiegel also notes that Louis Finkelstein is referred to in the preface to Hasdei David as ר’ אליעזר אריה נר”ו בהרב ר’ שמעון הלוי ז”ל, without his last name. Spiegel sees this as a way of hiding Finkelstein’s identity, just as Lieberman did with the others mentioned in the preface. One of the people Lieberman refers to is הרב ר’ יהושע נר”ו בהרב ר’ יהודה ליב who discovered the manuscript of R. Pardo. (This is R. Yehoshua Hutner.) Lieberman also mentions two other people, one who transcribed the manuscript and another who proofread the book. It is possible that one or more of these individuals did not want to be mentioned by name as helping Lieberman, and this explains why Lieberman abridged all the names, including Finkelstein’s. But I repeat, Lieberman’s name in the preface is not in code, as .ש.ל is how he always signed the end of the prefaces of his books.

Spiegel[4] also notes that in Sinai 85 (1979), p. 199, the following short piece is signed בלי שם.

It is known, Spiegel tells us, that this was written by Lieberman. He also mentions that there is a hint to Lieberman’s authorship in that all the letters in בלי שם are found in Saul Lieberman’s name. This is indeed significant, as it shows us that for whatever reason, Lieberman was not averse to writing anonymously. In fact, in 1932 Lieberman used the pseudonym .ל.ל when he published a note in Tarbiz.[5] In 1936 he again published a note with this pseudonym.[6]

When I first examined Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, I too thought that Lieberman must have written it, for the reasons already mentioned. What stood out most to me, as I have mentioned already, is that Lieberman in his many writings, including those that focus on the Jerusalem Talmud, never referred to the book even though it does the same thing what he was doing in Ha-Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto. I assumed that had anyone other than Lieberman written the book he certainly would have mentioned it, at least in the introduction to Ha-Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto, even if only to express his disagreement about certain matters. Obviously, Lieberman had a reason for not referring to this book, and I assumed it was because he did not want to associate his later scholarship with it.

Yet when I looked carefully at Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi and compared it to other writings of Lieberman on the very same sugyot, I was not able to find any parallels. This is so even though the book is written in the same style as Lieberman’s writings. Just when you would have expected some repetition from Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi in Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto and Tosefta ki-Feshutah, you find nothing.

I also noticed that there is a good deal of fraudulence in Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, and it is impossible to imagine that Lieberman, in his alter ego “Rosenberg,” would have been a part of this. For example, on p. 5 in the note he cites Solomon Buber from Ha-Levanon, Sep. 18, 1872, as stating that there is a Yerushalmi Kodashim in the Vatican. Yet if you look at Buber’s article you find that he says the exact opposite, that there is no such manuscript there. Buber further states that he doesn’t believe that there ever was a Yerushalmi Kodashim. What is the point of “Rosenberg” providing such misinformation other than to play games with the readers? On p. 30 n. 37, “Rosenberg” actually states that he thinks that portions of the Yerushalmi Kodashim published by Friedlaender are authentic. This makes no sense, as there was no manuscript to which Friedlaender could have added his own material.[7] All academic scholars in the 1920s knew this, so what kind of fraudulence is “Rosenberg” peddling here? Interestingly, on pages 3 and 8 “Rosenberg” also refers to the earlier work by the other Rosenberg (i.e., Friedlaender), the booklet Aneh Khesil. This must be seen as an inside joke, especially since the page number given is 36 but the booklet doesn’t have this many pages.

Only after I had gone through Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi did I learn that the entire book is a series of plagiarisms from earlier authors, as has been noted by Elyashiv Cherlow[8] and an anonymous commenter here. Cherlow also points out that “Rosenberg” quotes a Geniza text that he invented from thin air. I too found an example of the author’s plagiarism that is not noted by Cherlow or the anonymous commenter: The lengthy passage, with numerous sources, found on pp. 71-72 n. 57, is lifted word for word from Avigdor Aptowitzer’s article in Ha-Tzofeh le-Hokhmat Yisrael 1 (1911), pp. 87-88.

There are some other strange things in Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi. For example, what is one to make of the dedication to the Jewish communal leader Louis Marshall?

Since this post has dealt with Lieberman, even if only to reject the notion that he is the author of Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, let me add a couple of more points about him. From 1918-1962 there was an Orthodox publication called the Jewish Forum.[9] In the January 1961 issue there appeared an article by “Dayyan al-Yahud” sharply criticizing Conservative Judaism. In this article the author also took aim at Lieberman, referring to him as a “careerist”. He writes:

We ask, in all sincerity, where is the steadfastness of principle and consistent loyalty to Torah-Tradition on the part of the same Professor? This “guiding spirit” of the new kethubah, who only a few years ago, when the Agudath Harabbanim of the United States and Canada had declared Dr. Mordecai M. Kaplan under “herem” (anathema), himself recognized the “herem” as binding upon all Traditional Jews and refused to be in Kaplan’s company, as evidenced, in our presence, by his demonstrably stepping out of the Seminary elevator at the very entrance to the main building of the Seminary, no sooner than Dr. Kaplan had stepped in.

Such incongruous and compromising practices on the part of the Seminary’s present “scion” of Halakhah must of necessity lead to lack of reverence for time-honored traditions by its student body and graduates. No wonder that the latter, with few exceptions, are now groping in darkness and exhibit vacillation and uncertainty in their respective ministries.

Quite apart from the criticism of Lieberman, the passage is significant because the author testifies to having personally seen that Lieberman had previously observed the herem against Kaplan and refused to be in his presence.[10]

Who is Dayyan al Yahud? If you google the name, you will find that he also wrote articles critical of Kaplan and Heschel, yet none of the American authors who refer to Dayyan al Yahud identify who he is. He also wrote a number of articles under this pseudonym in Or ha-Mizrah. Yet his identity was never really a secret and is none other than the noted scholar Israel Elfenbein (1891-1964). The author of many works, Elfenbein is most known for his scholarly edition of Teshuvot Rashi (New York, 1943), which incidentally also includes notes from Louis Ginzberg. Elfenbein became a significant figure in American Orthodoxy, serving as editor of Or ha-Mizrah and education director of Religious Zionists of America. He was also honored with a Jubilee Volume (Jerusalem, 1963), which in addition to articles from various academic scholars, also has contributions from R. Eliezer Silver, R. Yehudah Gershuni, R. Nissan Telushkin, R. Leo Jung, and R. Menahem M. Kasher. Elfenbein also engaged in polemics against Conservative leaders. Yet one would not have expected his prominence in Orthodoxy, as in his early years Elfenbein received semikhah from the Jewish Theological Seminary and served as rabbi of the Conservative congregation Adath Israel in Nashville from 1915-1916.[11]

In truth, Elfenbein’s identification with Orthodoxy was a return to his youth, as before he came to America he had studied in Pressburg and had received semikhah from R. Shalom Mordechai Schwadron. That at least is the story told by his relative, Y. N. Adler,[[12] but being that Elfenbein came to America when he was fifteen years old, is it really possible that he received semikhah at such a young age?[13] Upon arriving in New York in 1906 he entered Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon (where his classmate was Bernard Revel, who himself had received semikhah at age 16).[14] With such a background in traditional Torah learning, how did Elfenbein end up at JTS?

Adler tells a fascinating story, different versions of which we know from other sources as well, although as far as I can tell, only the Rabinowitz article (see note 15) mention Elfenbein’s name. During Elfenbein’s time at RIETS—from other sources we know that the year was 1908—he and some friends wanted to study at a university (Yeshiva College did not yet exist). They therefore took the regents exam which allowed them to apply to institutes of higher learning. According to Adler, among the students who were part of this group, and who later became quite distinguished, were Rabbi Baruch Shapiro, who later served as rav in Seattle, Rabbi Louis Epstein, Rabbi Yehiel Kaplan, Dr. Israel Efros, Rabbi Solomon Goldman of Chicago, and Dr. Abraham Neuman.

This action, Adler tells us, greatly upset the rabbinic leadership of RIETS. In response to this, Elfenbein and his friends stopped learning at RIETS and set up a beit midrash, which they called Beit ha-Midrash ha-Elyon, in the Adass Bnei Yisrael synagogue of R. Solomon Elhanan Jaffe. (Other sources record the name as “Yeshivah le-Rabbanim”.) This beit midrash did not last long, and most of the students, including Elfenbein, transferred to JTS.[15]

Returning to Lieberman, there is another interesting comment in R. Dov Cohen’s Va-Yelkhu Shneiheim Yahdav, p. 168. He mentions how in Jerusalem Lieberman was treated with great respect at the Chevron Yeshiva, even after he had gone to the university. As for his going to JTS, Cohen recalls a biting hasidic comment about mitnagdim, that for Torah study a Litvak would even enter a church!

האיש היוה דוגמא למה שהיו החסידים טוענים על המתנגדים, כי התורה בליטא התקדשה עד כדי כך שעבורה היה מוכן הליטאי להכנס לכנסיה. . . [הנקודות במקור] אחר שהתגורר כמה שנים בירושלים, נמלך בדעתו כי מוטב שילמד באין מפריע. מאחר שהציעו לו משרה חשובה בסמינר קונסרבטיבי באמריקה, נסע שם וקיבלה. הוא לא שיתף עמם פעולה בסיוע לדרכיהם הנלוזות, חלילה. גם שם היה יושב בחדרו ועוסק בגמרא וכן בחיבור ספריו על התוספתא. זכורני שבכינוס של אגודת הרבנים באמריקה, בו השתתפתי, התייחסו אליו כאל “אחד משלנו” שיכול לעזור ולסייע, אף שהוא “אצלם”. גם הרב אברמסקי, התקיף והלוחם, קיבלו בכבוד גדול. שמעתי גם כן, שהוא החזיק מכספו כמה וכמה בני תורה בירושלים.

Regarding Lieberman, I have one final point to make. In Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, p. 7, I mentioned a November 1930 letter from Lieberman to Louis Ginzberg in which Lieberman writes that he began working on a great project on the Jerusalem Talmud, but had to stop because one cannot work on Berakhot without knowing all of the Yerushalmi. Only when he finished the entire Jerusalem Talmud did he pick up the project again. I added that the project Lieberman refers to must be Ha-Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto, which appeared in 1935.

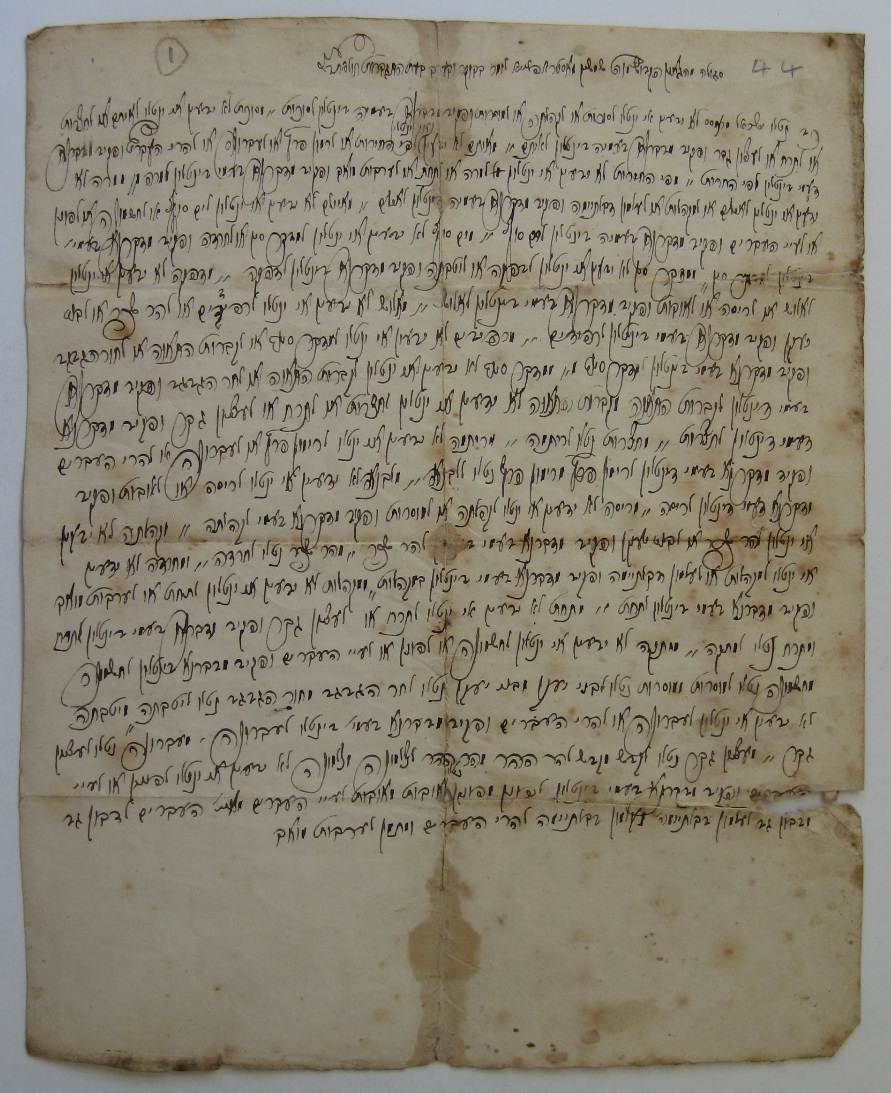

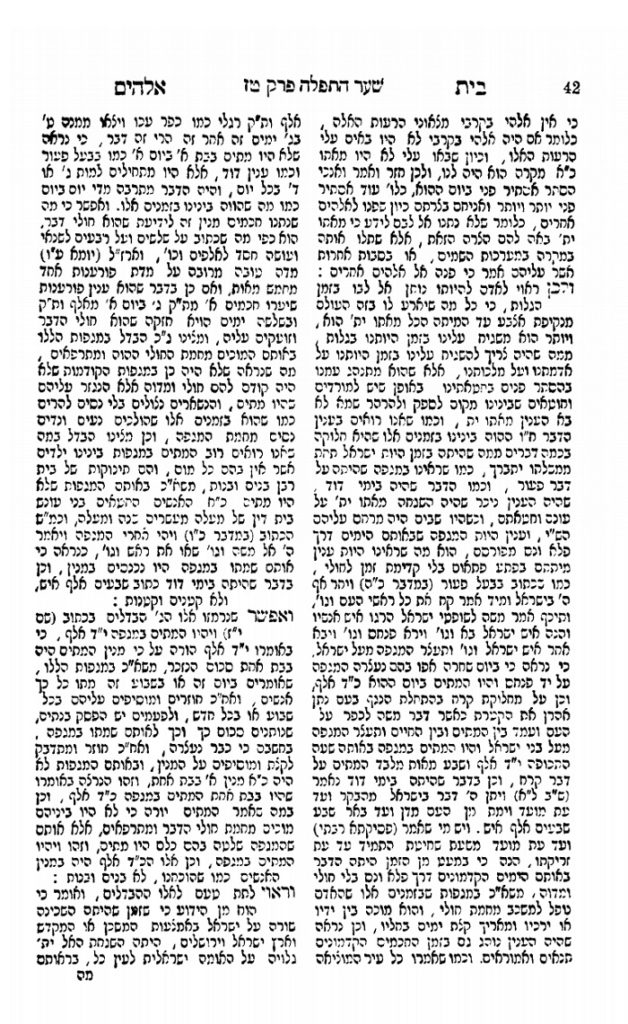

Here is the relevant section of Lieberman’s letter:

התחלתי ג”כ בעבודה גדולה על שדה הירושלמי אבל הוכרחתי לעזוב אותה מפני שאי איפשר [!] לעבוד ב”ברכות” כל זמן שאינם יודעים [!] את כל הירושלמי עד “נדה” ורק בקיץ זה אחרי גמר הירושלמי שבתי עוד הפעם לברכות

The problem with my assumption that Lieberman’s project was Ha-Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto is that this book includes his commentary on Shabbat, Eruvin, and Pesahim, and in his letter he speaks of returning to Berakhot. Yet I didn’t know of anything else that could fit the description of a great project on the Yerushalmi during this time period.

Dan Rabinowitz has, I think, provided the answer. He called my attention to Tovia Preschel’s article in Ma’amrei Tuviah, vol. 2, pp. 155-156. Preschel recounts that not long after Lieberman settled in Jerusalem in 1928, he was asked by R. Michel Rabinowitz to assist him in translating the Yerushalmi into Hebrew. Lieberman replied that he had never studied the Yerushalmi and he can’t translate a work that he doesn’t know. He asked for time to immerse himself in it, and for the next year and a half he completed the Yerushalmi a few times. In the end, the Hebrew translation did not appear, but I have to agree with Dan that it is this project that Lieberman is referring to in his letter to Ginzberg, not Ha-Yerushalmi ki-Feshuto.

2. Since I mentioned RIETS earlier in this post, let me add the following. In 2022 the ArtScroll biography of R. Yitzchok Scheiner appeared, authored by Nachman Seltzer.[16] This book tells how R. Scheiner was living in Pittsburgh and was intending to attend a local university. However, a fundraiser for RIETS (i.e., Yeshiva College) was in Pittsburgh and convinced R. Scheiner’s parents to send him there. Seltzer, p. 30, includes all of one paragraph dealing with R. Scheiner’s time at Yeshiva College. I quote it here, followed by the two subsequent paragraphs.

The winter that Yitzchok Scheiner enrolled at Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon was cold, dark, and dreary. Though he had been raised in Pittsburgh and was no stranger to the grayness and never-ending winter months, the young man came down with the kind of cold that turned into something more serious and that he couldn’t seem to shake.

The illness that plagued him for so many months would turn out to be a blessing in disguise, because it forced him to find a place to convalesce.

In those early years, Jewish camps suitable for yeshivah bachurim were few and far between, which is why, come summertime, Yitzchok Scheiner found himself on a bus headed up to the mountains, to the one and only Camp Mesivta, founded by the legendary R. Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz. It was a summer that would change his life.

Seltzer continues by describing how at camp R. Scheiner was influenced to enroll in Torah Vodaath at the end of the summer. Interestingly, the book never refers to Yeshiva College, only Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon, but R. Scheiner was enrolled in the college, in addition to studying in the yeshiva.

According to Seltzer, R. Scheiner was only at Yeshiva College for less than one academic year, for he tells us that he enrolled in the winter. As far as I know, this is incorrect, and he was at Yeshiva College the entire academic year 1939-1940. In fact, he was on the chess team and was even chosen as the captain.

This page from the Yeshiva College yearbook, Masmid 1940, can be seen here.

What complicates matters is that R. Scheiner himself said that he was at Yeshiva College for two years (and this was after a semester at the University of Pittsburgh, a point which is not mentioned by Seltzer).[17] According to the records of the University of Pittsburgh, Office of the University Registrar, Isadore Leon Scheiner attended the University of Pittsburgh for a semester in 1938-1939, during which time he took seven classes (I presume that the semester ended in January.) Even if R. Scheiner entered Yeshiva College for the spring 1939 semester, his time there would have been three semesters, not two years, so presumably when he said “two years” he was not being exact. By fall 1940 R. Scheiner – who was on track to graduate in 1942 – had left Yeshiva College. We know this because the Sep. 18, 1940 issue of the Yeshiva College Commentator mentions that he is no longer there.[18]

In discussing his time at Yeshiva College, R. Scheiner states: “When I got there, I discovered that the other students did not take Torah learning as seriously as I wanted to or as seriously as some of the rabbeim wanted them to, so I left.”[19]

Interestingly, in an interview that appeared on Matzav.com here, R. Scheiner does not mention that he attended Yeshiva College, or perhaps this was censored by Matzav.com:

Where did the Rosh Yeshiva learn in his youth?

HaRav Scheiner: I learned in the United States, in Yeshivas Torah Vodaas, from Rav Reuven Grozovsky zt’l, Rav Boruch Ber’s son-in-law and from Rav Shlomo Heiman zt’l. There was a group of students who would go to Lakewood to hear Rav Aharon Kotler’s shiurim and I sometimes joined them. Some of them stayed on afterwards to learn there permanently, among them HaRav Elya Svei. The Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Reuven Grozovsky, made my shidduch.

R. Scheiner would later teach at the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in Montreux, Switzerland, where he developed a close relationship with R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg who lived in the town. For R. Scheiner, it was a great privilege to be in such close proximity to one of the gedolei Yisrael, and they spent much time together “talking in learning.” When R. Scheiner moved to Jerusalem, they continued their relationship by mail, with many Torah letters going from one to the other.

Here is a never-before publicized picture of R. Weinberg, together with R. Scheiner. The man in the middle who is speaking is R. Meir Just of Amsterdam. I thank Israel Bollag for sending it to me. (In a future post I will include more unknown pictures of R. Weinberg, including some in color.)

Unfortunately, the only mention of R. Weinberg in Seltzer’s book is in the following paragraph (p. 81).

There were other great Torah scholars teaching at the yeshivah in Montreux alongside Rav Yitzchok. One of them was R’ Betzalal Rakow, who would later be appointed rav of Gatesehad, England. R’ Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, also known as the Seridei Eish, also spent time in the yeshivah.

R. Weinberg never officially taught at the yeshiva, although he would sometimes give the opening shiur of the semester. I assume this is what Seltzer means by “spent time in the yeshivah.” The real problem with the paragraph is that it makes it seem as if these three figures were colleagues, and at the same level. The truth is that both R. Scheiner and R. Rakow regarded R. Weinberg as a rebbe of sorts, which is understandable, especially as he was decades older than them.

3. In my last post here, I linked to a lecture from Professor Isadore Twersky that I found at the University of Scranton. Dr. Marc Herman called my attention to another video here in which Prof. Twersky appears. Unlike the video I posted, in this video you can hear Prof. Twersky very clearly. I was at Harvard when this presentation took place, yet I had no idea that Twersky was ever on this panel.[20] I think people will find it interesting that the moderator is none other than Alvin Bragg, the current Manhattan District Attorney. Prof. Harvey Mansfield also appears and is provocative as always (this time saying that grade inflation came about because of Affirmative Action).

4. Earlier in the post I mentioned Mordecai Kaplan, so here is a good place to add another point about him. Kaplan’s father, R. Israel, was close to R. Isaac Jacob Reines. (Mordecai Kaplan was actually born in Svencionys, where R. Reines had served as rav.) This explains why Kaplan, who had already been ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary, turned to R. Reines when he wished to acquire a semikhah from a well-known rabbi. Everyone who writes on this matter refers to Kaplan traveling to Europe on his honeymoon after his June 2, 1908 wedding, at which time he also received semikhah from R. Reines who was then serving as rav in Lida.[21] People have generally assumed that he traveled to Lida to receive the semikhah.

In 1994 Jacob J. Schacter published a picture of R. Reines’ semikhah, dated 28 Elul, 5668 (Sep. 24, 1908). From this document we see that Kaplan actually met R. Reines in Frankfurt, and that is where they “spoke” in learning, following which R. Reines gave him semikhah. Schacter writes: “While traveling through Frankfurt he met his father’s old friend, Rabbi Yizhak Reines, spent some time with him, and received rabbinic ordination from him.”[22] This is based on Kaplan’s own recollection where he writes: “I had the opportunity to meet the late Rav Yitzhak Reines in Frankfort-on-the-Main and to obtain the requisite Hatarat Hora’ah from him.”[23]

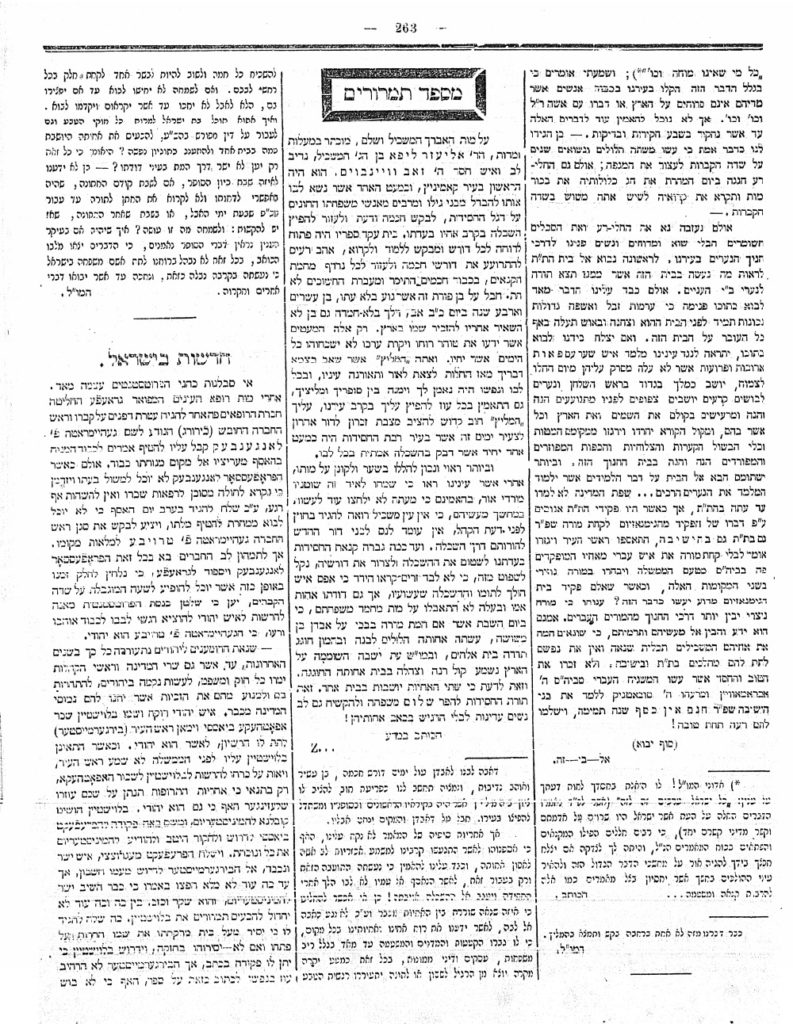

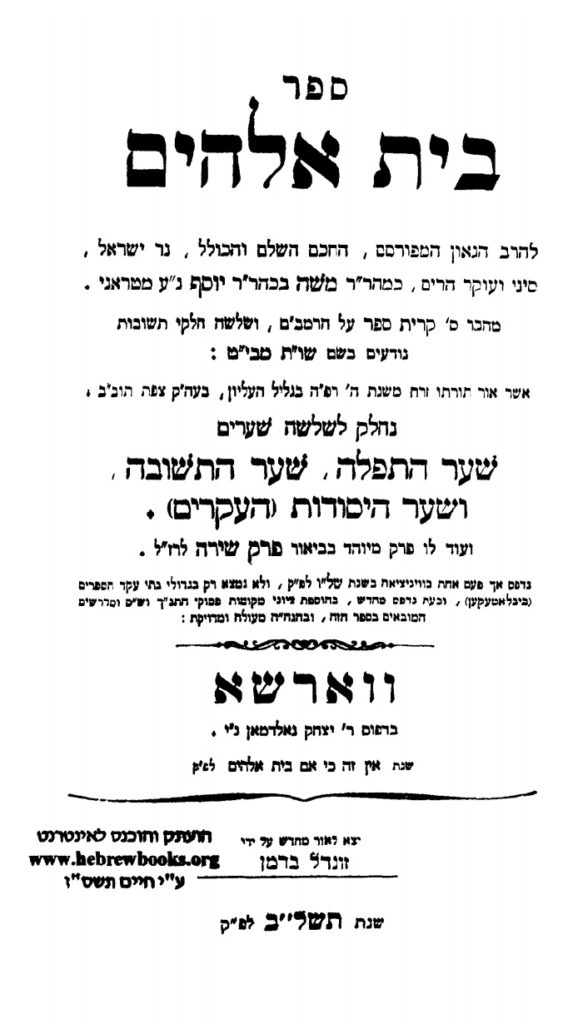

Did Kaplan just happen to be passing through Frankfurt while on his honeymoon? The answer is no, and I’m happy to share something that is completely unknown: Kaplan was actually in attendance, together with R. Reines, at the 1908 Frankfurt Mizrachi conference. Here is the report of the conference in the Sep. 4, 1908 issue of the Cracow newspaper Ha-Mitzpeh. Kaplan is mentioned in the first paragraph.

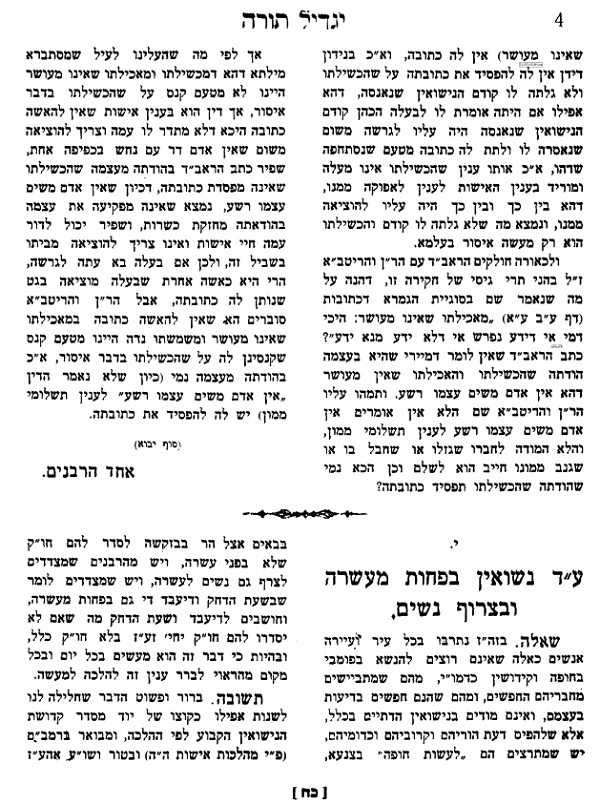

5. In Hakirah 32 (2022), I published a number of letters from R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik. One of them was sent to Professor Marvin Fox who had asked the Rav about the synagogue he attended, Agudas Achim of Columbus, Ohio. The synagogue had recently built a new building and instituted mixed seating.[25] Fox also turned to R. Mordechai Gifter. Here is R. Gifter’s letter to Fox.

Here is a draft of a Hebrew letter from Fox to the Rav.

It is not known if Fox ever sent the Hebrew letter, or if he sent an English one. I would presume the latter, as the Rav’s reply, that appears in Hakirah, is in English.

Fox’s archive also contains the following English letter. In the Rav’s June 1955 letter in Hakirah, he is responding to Fox’s 1955 question about praying in a synagogue without a mechitzah (i.e., Agudas Achim). The letter below is from a later period and asks about praying in the synagogue’s beit midrash, in which no women are present. (As Fox’s son Avi informed me, Fox was at Harvard during much of 1956; this letter to the Rav is from when he returned to Columbus after his time in Boston.) Fox’s archive does not contain a reply to this letter.

Here is the letter that Fox sent to Rabbi Samuel Rubenstein, the rabbi of Agudas Achim.

Fox’s reference in the Hebrew letter concerning the synagogue of R. Leopold Greenwald—of Kol Bo al Avelut fame—as not having a regular mehitzah is of interest. R. Greenwald was a strong opponent of anything smacking of reform. He himself spoke strongly against mixed seating in the synagogue and would never enter a synagogue with such an arrangement. Yet his own synagogue, Beth Jacob, against his wishes also decided to remove the mehitzah. Since it still kept separate seating, R. Greenwald felt that he could remain as rabbi even though he was not happy with the situation.[25]

While Beth Jacob remained in the Orthodox fold, and would later reinstall a regular mehitzah, in 2004 Agudas Achim decided to affiliate with the Conservative movement.

All the letters published above are found in the Marvin Fox Papers, Box 11 and Box 29, Brandeis University, and appear here courtesy of the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis University.

Since in this post I mention both R. Bernard Revel and R. Mordechai Gifter, let me add one more point regarding them. In 2011 Milei de-Igrot, vol. 2, appeared. This contains the letters between R. Gifter and his rebbe at RIETS, R. Moshe Aharon Poleyeff.

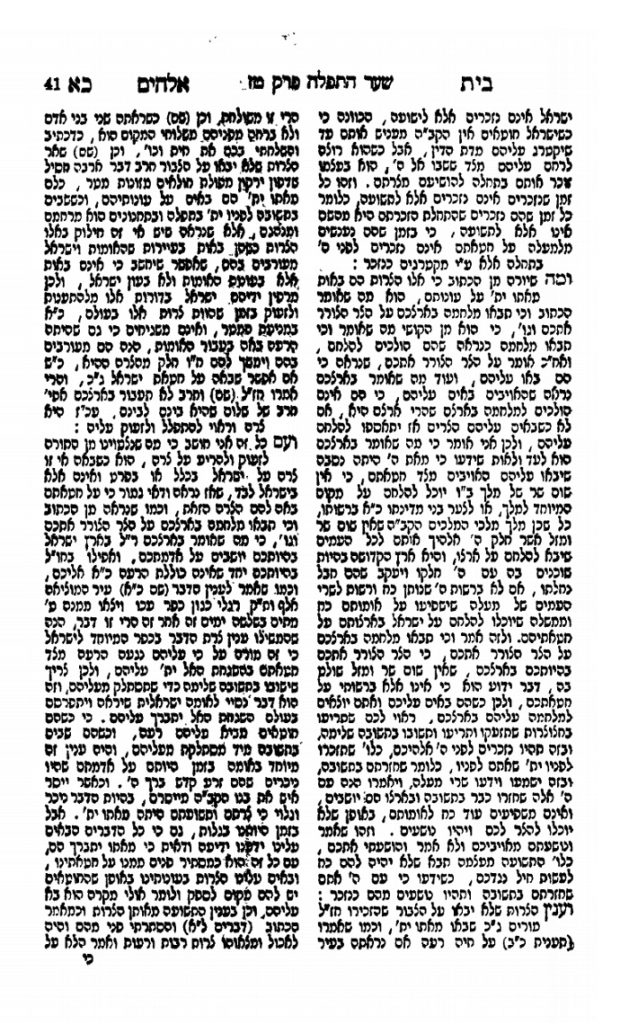

In addition to all the Torah the volume contains, it also offers us insights regarding both of these rabbis’ personalities and the history of Orthodoxy in the U.S. and Lithuania. Here is p. 168.

In addition to describing the incredible effect that Telz had upon him, R. Gifter also levels strong criticism against the אדמון running Yeshiva College who is destroying young people by exposing them to heresy. This refers to R. Revel who had a red beard. In fact, R. Aharon Rakeffet informed me that the opponents of R. Revel used to refer to him in a disgusting way as the “reiter hunt”.

6. In my last post I had the following quiz questions:

1. Which Hebrew book was the first one to use footnotes (and the footnotes even used Arabic numerals)?

2. Point to a halakhah on Pesach that the Shulhan Arukh decides in accord with the Rosh, while the Rama records the practice in accord with the Rif and the Rambam.

The answer to no. 1 is R. Noah Hayyim Zvi Hirsch Berlin, Ma’yan ha-Hokhmah (Rodelheim, 1804).[26] No one answered this question.

The answer to no. 2, which a few people answered correctly, is found in Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 474. Here R. Joseph Karo rules like R. Asher ben Jehiel, cited in Arba’ah Turim, Orah Hayyim 474, that there is no blessing on the second and fourth cups of wine at the Passover seder. R. Moses Isserles rules like the Rif, Pesahim 24a in the Alfasi pages, and the Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Hametz u-Matzah 8:5, 10, that one recites the blessing on all four cups.

*********

[1] “Pesukei Mikra she-be-Talmud,” Jeschurun 4 (1923), pp. 43-47, available here,“Le-Heker ha-Talmud ha-Yerushalmi,” ibid., pp. 109-112, available here, ibid., 5 (1924), pp. 18-20, available here.

[2] See Elijah J. Schochet and Solomon Spiro, Saul Lieberman: The Man and His Work (New York, 2005), p. 8.

[3] (Jerusalem, 2014), p. 46 n. 151.

[4] Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri: Be-Sha’arei ha-Defus, p. 48, n. 161.

[5] “Od ‘le-Tikunei Girsaot be-Sifrei,’” Tarbiz 3 (1932), p. 466.

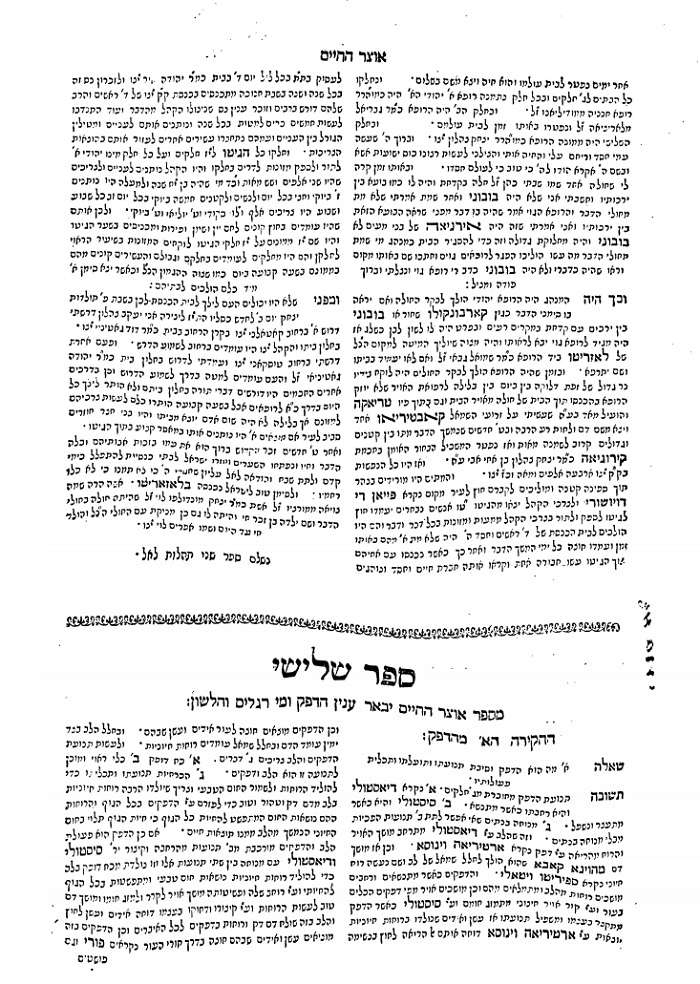

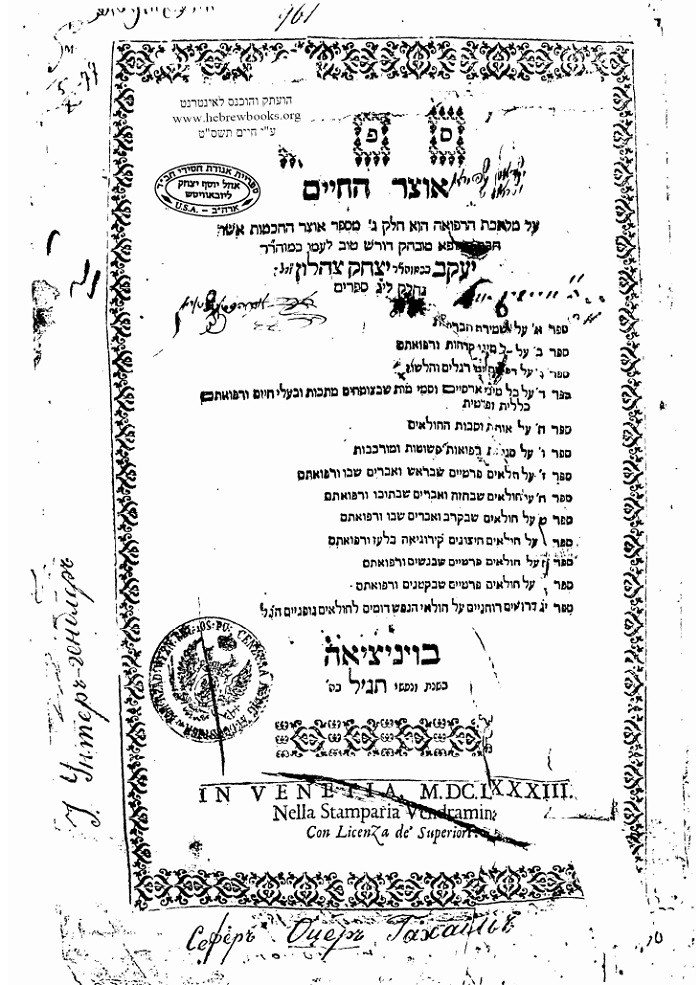

[6] See B. M. Lewin, ed., Alumah (1936), p. 156. This source and the prior one are listed in Tovia Preschel’s bibliography of Lieberman’s writings here. While this is a very complete bibliography, it omits one source that is completely unknown, and which fans of Lieberman will certainly want to examine. Here is a short article by Lieberman that appeared in Otzar ha-Hayyim 10 (1934), pp. 83-84.

[7] In the article in Jeschurun, “Le-Heker ha-Talmud ha-Yerushalmi,” p. 110, “A. Rosenberg” states that the Jerusalem Talmud to Kodashim is lost, and he does not mention Friedlaender. Regarding the Yerushalmi Kodashim, I recently found that R. Mordechai Vorhand, Be’er Mordechai, p. 152, states that he is not going to take a stand regarding its authenticity. This is quite strange as Be’er Mordechai appeared in 1927 and the forgery had already been established for a number of years. Even stranger is that R. Menahem Mendel Kirschbaum, Menahem Meshiv, vol. 2, p. 8, also cites the Yerushalmi Kodashim. His responsum is from 1933 and Menahem Meshiv, vol. 2, was published in 1938. How could anyone at this late date still cite the Yerushalmi Kodashim? Interestingly enough, R. Kirschbaum disputes “the commentator’s” (i.e., Friedlander’s) understanding of the passage he is dealing with. Of course, “the commentator” is none other than the author (forger) of this passage, who presumably knows what he himself intended. This point is made by R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin, Soferim u-Sefarim, vol. 1, p. 307. In Menahem Meshiv, vol. 1, p. 163 (published in 1936), R. Kirschbaum shows that he is aware of the forgery, so he must have assumed that despite the forgery, some of the Yerushalmi Kodashim published by Friedlander is authentic. This explains how in Menahem Meshiv, vol. 1, pp. 70, 234, he cites Yerushalmi Bekhorot as authentic. R. Yeruham Fishel Perla states that portions of the Yerushalmi Kodashim are indeed authentic, while Friedlander forged the rest. See his edition of R. Eshtori ha-Parhi, Kaftor va-Ferah, p. 145b.

[8] “Toldot ha-Nusah shel ha-Talmud ha-Yerushalmi: Iyunim be-Kit’ei ha-Genizah,” Tarbiz 87 (2020), p. 610 n. 70.

[9] See Ira Robinson and Maxine Jacobson, “When Orthodoxy was not as Chic as it is Today”: The Jewish Forum and American Modern Orthodoxy,” Modern Judaism 31 (Oct. 2011), pp. 285-313.

[10] Regarding Lieberman and the herem against Kaplan, see my Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, pp. 19-20. See my post here for the text of the herem against Kaplan. Here is a tidbit that is not generally known: As late as 1945, when Kaplan’s theological views were public knowledge, he was still a member of the Rabbinical Assembly’s Committee on Jewish Law. See David Golinkin, ed., Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement 1927-1970 (Jerusalem, 1997), vol. 1, p. 155.

[11] See here, here, and here.

[12] See Adler’s article in the Elfenbein Jubilee Volume, pp. 9-14. Adler twice says that Elfenbein studied nine years at RIETS, but this is an obvious mistake, and is contradicted by the dates in Adler’s own article.

[13] For an earlier post in which I deal with young rabbis, see here. R. Ovadya Hoffman called my attention to another young rabbi (I also mention Hoffman in the post just linked as he noted an additional young rabbi): It is reported R. Yitzhak Isaac Katz (1753-1787) was thirteen years old at his marriage and was also appointed rabbi of Koretz at this time. His Wikipedia entry is here. The information about him becoming rav at age thirteen in found here in the biographical introduction to his Zikhron Kehunah (Lvov, 1863). I don’t know of any other examples of a thirteen-year-old who served as the official rav of a community. In the Encyclopaedia Judaica entry on R. Meshullam Roth (called “Rath” in the EJ), written by R. Mordechai Hacohen, it states that he was ordained at the age of 12 by R. Isaac Shmelkes and R. Jacob Teomim. This detail is not found in any of the sources listed in the bibliography so it is hard to know where R. Hacohen came to this information. One of the descendants of R. Roth told me that he never heard that R. Meshullam received semikhah at age 12.

[14] Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Bernard Revel: Builder of American Jewish Orthodoxy (Jerusalem/New York, 1981), p. 30.

[15] For more on student restlessness at RIETS and the 1908 student strike, see Gilbert Klaperman, The Story of Yeshiva University (London, 1969), chs. 5-7 (on pp. 115ff. he discusses the Elfenbein group); Hayyim Reuven Rabinowitz, “60 Shanah li-Shevitot bi-Yeshivat R. Yitzhak Elhanan,” Ha-Doar, June 14, 1968, pp. 552-554. See also Eli Genauer’s Seforim Blog post here which includes R. Baruch Shapiro’s recollections of the 1908 student strike.

[16] Nachman Seltzer, Rav Yitzchok Scheiner: The Life and Leadership of the Kamenitzer Rosh Yeshivah (Brooklyn, 2022).

[17] See the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 1, 1998, p. A-14; Samuel Heilman, Defenders of the Faith (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1992), p. 262. Chapter 17 in Heilman’s book is an interview with R. Scheiner, and as Heilman informed me, R. Scheiner told him that was at Yeshiva College for two years. He must have also provided this information to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. See also here.

[18] This page from the Commentator was posted by Dovi Safier here.

[19] Heilman, Defenders of the Faith, p. 262. I have corrected Heilman’s spelling of “rabbaim” to “rabbeim”.

[20] Regarding Twersky, I found it interesting that in a recent article Levi Cooper refers to him as a “noted academic and hasidic master.” See Cooper, “Jewish Law in the Beit Midrash of Hasidism,” Dine Israel 34 (2020), p. 63.

[21] See e.g., Mel Scult, Judaism Faces the Twentieth Century: A Biography of Mordecai Kaplan (Detroit, 1993), pp. 26, 96.

[22] Jacob J. Schacter, “Mordecai M. Kaplan’s Orthodox Ordination,” American Jewish Archives 56 (1994), p. 6.

[23] Ibid., p. 7. Schacter , ibid., also writes that R. Reines did not rigorously examine Kaplan, and therefore the semikhah should not be “considered an indication of any advanced talmudic scholarship on Kaplan’s part.” This reminded me of something interesting regarding the name “Mordechai”. According to Tosafot, Menahot 46b, s.v. amar, the name Mordechai was a second name given to those who showed great intellect and knowledge: בקיאים בעלי שכל ומדע. See also Tosafot, Bava Kamma 82b, s.v. ve-al:

דכל אותן שהיו בקיאים ברמזים ובלשונות היו נקראים על שם מרדכי לפי שהוא היה ראש וחכם להכיר

In Italy, people with the Hebrew name Mordechai were often named Angelo in Italian. This is likely because of the rabbinic identification of the biblical Mordechai with the prophet Malachi (and Malachi is akin to מלאך, i.e., “angel”). See Megillah 15a; Moshe David Cassuto, Ha-Yehudim be-Firentzi bi-Tekufat ha-Renesans, trans. Menahem Hartom (Jerusalem, 1967). p. 183.

[24] According to Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern Community: Columbus Ohio, 1840-1975 (Columbus, 1979), p. 348, the synagogue also had mixed seating even before the new building, but as we see from Fox’s letter this was not the case.

[25] See Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern Community, p. 348; Adam S. Ferziger, Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism (Detroit, 2015), p. 26; Rivka Schiller’s article on Greenwald here.

[26] This is noted by R. Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger, Ha-Yeshivah ha-Ramah be-Fiorda (Bnei Brak, 2010), vol. 2, p. 115. How is the first word of the sefer, מעין, to be pronounced? It has become common in modern Hebrew to pronounce it as “ma’ayan”. Yet this is not how it appears in the Bible. There the word has a shewa under the ayin, מַעְיׇן, so the word is to be pronounced ma’yan. The change in pronunciation of this word is noted by Joshua Blau, “Al ha-Mivneh ha-Murkav shel ha-Ivrit ha-Hadashah le-Umat ha-Ivrit she-ba-Mikra,” Leshonenu 54 (1990), p. 106. The plural of מעין is מַעְיָנוֺת, as seen in Is. 41:18, Prov. 8:24, II Chron. 32:4 (Ps. 104:10 has מַעְיָנִים). Therefore, it is unfortunate that the popular Bergen County, N.J. girls’ school has as its name “Ma’ayanot,” instead of the correct word, “Ma’yanot”. Yet in conversation, it appears that pretty much everyone seems to pronounce it correctly as Ma’yanot.

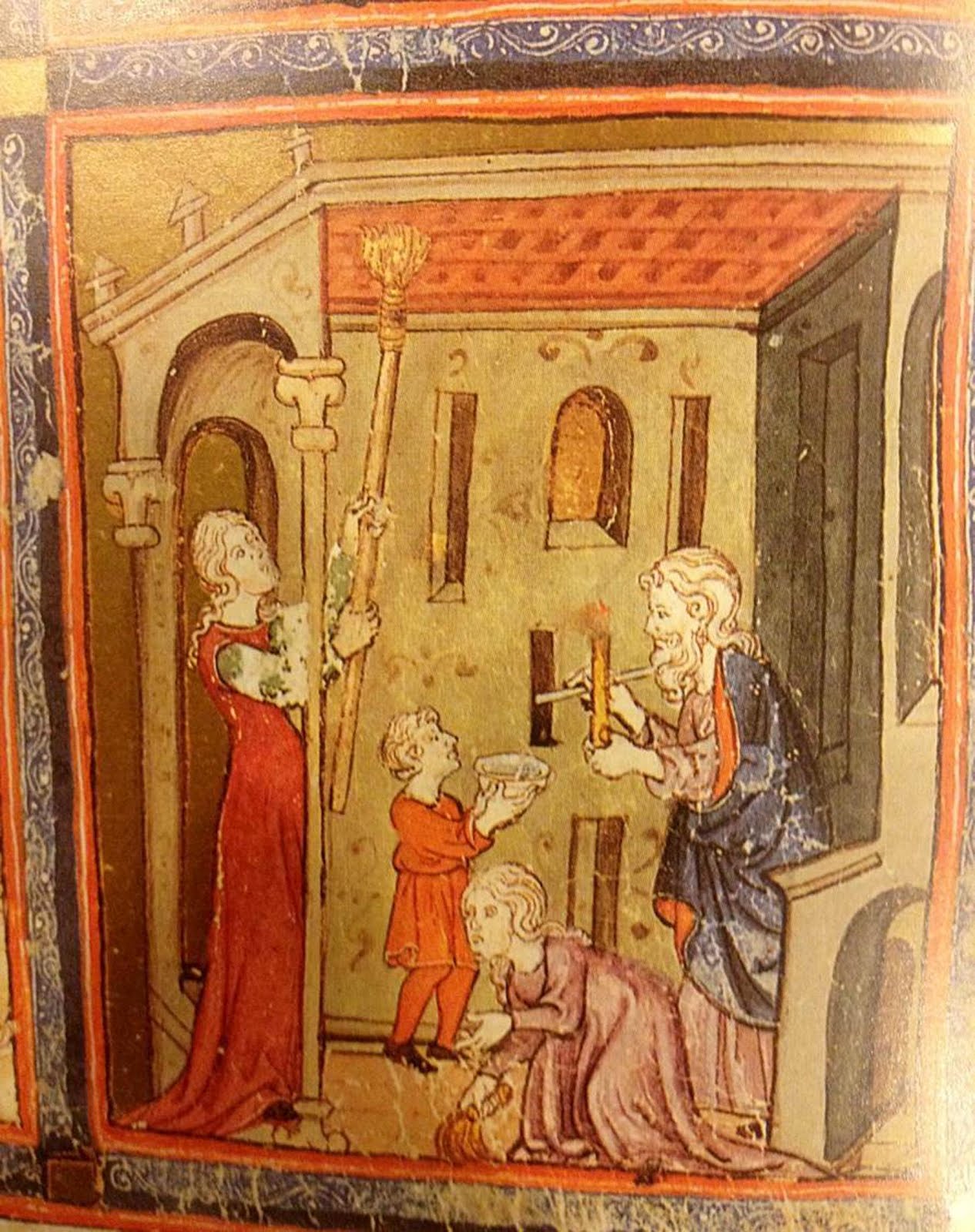

As detailed in chapter 8 of Epstein’s Medieval Haggadah, the early 14th Century Golden Haggadah is perhaps the most female-centric Haggadah and may have been commissioned for a woman. That manuscript emphasizes the unique, positive, and critical role women played in the Exodus narrative. Although it also depicts the practice of overzealous cleaning with a woman sweeping the ceiling. The 1430 Darmstadt Haggadah has a full-page illumination of women teachers, but its connection to the text is opaque. Finally, we argue that one printed Haggadah uses a subtle element in explicating the midrashic understanding of the separation of couples as part of the Egyptian experience.

As detailed in chapter 8 of Epstein’s Medieval Haggadah, the early 14th Century Golden Haggadah is perhaps the most female-centric Haggadah and may have been commissioned for a woman. That manuscript emphasizes the unique, positive, and critical role women played in the Exodus narrative. Although it also depicts the practice of overzealous cleaning with a woman sweeping the ceiling. The 1430 Darmstadt Haggadah has a full-page illumination of women teachers, but its connection to the text is opaque. Finally, we argue that one printed Haggadah uses a subtle element in explicating the midrashic understanding of the separation of couples as part of the Egyptian experience.

After completing the Haggadah, Moss was asked to reproduce it, and, with Levy’s permission, produced, what the former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Bornstein, described as one of the greatest examples of 20th-century printing. The reproduction, on vellum, nearly perfectly replicates the handmade one. This edition was limited to 500 copies, all of which were sold. From time to time, these copies appear at auction and are offered by private dealers, a recent copy sold for $35,000. President Regan presented one of these copies to the former President of Israel, Chaim Herzog, when he visited the White House in 1987. While that is out of reach for many, this version is housed at many libraries, and if one is in Israel, one can visit Moss at his workshop in the artist colony in Jerusalem, where he continues to produce exceptional works of Judaica and view the reproduction. There is also a highly accurate reproduction, on paper that is available (deluxe edition) and retains the many papercuts and some of the other original elements, that is still available. This edition also contains a separate commentary volume, in Hebrew and English. (There is also one other available version that simply reproduces the pages, but lacks the papercuts.)

After completing the Haggadah, Moss was asked to reproduce it, and, with Levy’s permission, produced, what the former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Bornstein, described as one of the greatest examples of 20th-century printing. The reproduction, on vellum, nearly perfectly replicates the handmade one. This edition was limited to 500 copies, all of which were sold. From time to time, these copies appear at auction and are offered by private dealers, a recent copy sold for $35,000. President Regan presented one of these copies to the former President of Israel, Chaim Herzog, when he visited the White House in 1987. While that is out of reach for many, this version is housed at many libraries, and if one is in Israel, one can visit Moss at his workshop in the artist colony in Jerusalem, where he continues to produce exceptional works of Judaica and view the reproduction. There is also a highly accurate reproduction, on paper that is available (deluxe edition) and retains the many papercuts and some of the other original elements, that is still available. This edition also contains a separate commentary volume, in Hebrew and English. (There is also one other available version that simply reproduces the pages, but lacks the papercuts.)