Dr. Samuel Vita Della Volta (1772-1853): An Underappreciated Bibliophile and his Medical “Diploma”tic Journey

Dr. Samuel Vita Della Volta (1772-1853): An Underappreciated Bibliophile and his Medical “Diploma”tic Journey

Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

I came upon the name Samuel Vita Della Volta through my usual historical pathway, the world of Jewish medical history, and my continued quest for medical diplomas of Jewish physicians from the premodern era. While the lion’s share of the diplomas I have identified come from the University of Padua,[1] there are some extant Jewish diplomas from other Italian universities, including Siena, Rome, and Ferrara. One of two Jewish diplomas I have procured from the University of Ferrara is that of Samuel Vital Della Volta, a graduate of 1802.

From an artistic perspective, it pales in comparison to the diplomas of his Paduan predecessors. See, for example, the diploma of the 1695 Jewish Padua graduate, Copilius Pictor (AKA Jacob Mehler), below.[2]

In contrast to this profusely hand illustrated spectacular example of Renaissance art, Della Volta’s is a templated diploma with both text and illustration printed. Only the graduate’s particulars are written, or I dare say squeezed in, by hand. To be fair, by this time not all Padua medical diplomas were as ornate as in the past, as evidenced by the diploma of Andrea di Domenico Rossi (Padua, 1788).[3]

However, the university did not entirely abandon its practice of issuing such diplomas, as evidenced by the diploma of Carlo Tomasini (Padua, 1794).[4]

The diploma below of Jewish Padua graduate Rafael Luzzatto from 1797[5] is more in line with Della Volta’s, though at least Luzzatto’s diploma was hand calligraphed.[6]

This diploma bears the invocation, “In Dei Nomine Amen” (in the name of God, Amen), typical for the Jewish student, instead of the standard invocation, “In Christi Nomine Amen” (in the name of Christ, Amen), used for the Christian students. Close inspection of this diploma reveals that the word “Dei” was written over an erasure of a longer word.

I have a strong suspicion that this was a standard templated diploma and that the calligrapher erased the word “Christi” and replaced it with “Dei.”

While the medical diplomas of the Jewish students of Padua,[7] as well as those from other universities such as Siena,[8] contained unique emendations, one finds no such alterations in Della Volta’s case.[9]

What caught my attention about Della Volta’s diploma was not its esthetics, or lack thereof, but rather its place of residence. This lackluster diploma currently resides in Budapest, Hungary in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The extant diplomas I have identified can be found mainly in Italy, Israel, and the United States. While each diploma has had its unique journey, these are by and large locations where the physicians lived, or their descendants migrated. For example, the diploma of Isaac Hellen can be found in a library in Germany,[10] but this is where Hellen lived and practiced. Della Volta was a Mantuan physician who lived and died in Italy. There is no record of his descendants migrating to Hungary. By what route then did this document reach such a wayward destination? Tracing the circulation of Jewish books “through time and place” is the laudable goal of the wonderful “Footprints” project.[11] While one may not always be able to track the exact journey of a book or manuscript through time, in this case we possess a passport of sorts with only three stops over some two hundred years that lead us directly to our final destination. The origin of this journey lies in the lifelong pursuits of our graduate.

Samuel Vita Della Volta (שמואל חי מלאוולטא) (1772-1853) was a physician and scholar born in Mantua whose writings include Biblical and Talmudic commentaries, sermons, and responsa. His works remain in manuscript and to my knowledge he has not been the subject of an academic biography.[12]

As a modest initiation into his writings, I share with you some observations from a few chapters selected from his unpublished work, Dan Yadin (1797).[13] The work is a miscellany of responsa and halakhic discussions. While the topics I have chosen are medical in nature, this reflects more my interest than the nature of the work.

Chapter 8 – Tefillin and Apoplexy (Stroke)[14]

This chapter takes the form of a classic responsum. The question is about a person who suffers from apoplexy, what today we would call a stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA).

While his cognitive function remains intact, he has lost motor function and sensation of his left arm. Is he still obligated to put on his tefillin shel yad, and if so, on which hand?

One of the more remarkable descriptions in Jewish literature of a stroke and its subsequent religious impact appears in the introduction to a work by another Jewish physician, Abraham Portaleone (d. 1612).[15] Portaleone came from a long line of physicians and graduated the University of Pavia in 1563.[16] He served as physician for the Dukes of Mantua, receiving special permission from Pope Gregory XIV to treat Christian patients. While he authored a number of medical works, it is only later in life that he wrote his Shiltei Ha-Gibborim on religious matters. The passage below from the book’s introduction explains why:

In June of 1605, Portaleone, a renowned and accomplished physician, reports how he experienced the sudden loss of function of the left side of his body, incapacitating him for some nine months. While he does not discuss how he observed the mitzvah of tefillin, he does mention his prayer, supplication, repentance, and religious self-reflection, which led him to undertake the writing of his magnum opus. This encyclopedic work was written for his children as a guide to proper religious prayer and observance,[17] focusing on the Temple service. It includes chapters on the musical instruments of the Beit Ha-Mikdash, the composition of the incense, and the details of the daily sacrifices. Della Volta would likely have read, if not owned, this work.

Returning to the halakhic question, Della Volta cites the Shevut Yaakov’s case of one born with only one arm on the right.[18] Rabbi Reischer debates whether such a person would be free of any obligation as he does not possess a yad keihe (non-dominant arm); or whether perhaps since he was born this way, his sole arm has the status of both a dominant and non-dominant arm combined. Rabbi Reischer accepts the latter approach and as such, requires the donning of tefillin. One who sustains a traumatic complete amputation of his non-dominant arm, however, would no longer be required to wear tefillin on that arm. (The obligation to wear tefillin shel rosh remains undisturbed.) Support for this position comes from Rama, the Bach and Maḥzik Brakhah. Della Volta argues that this would not apply to his case, where the physical arm is completely intact, albeit nonfunctional. With additional support from Rabbi Yeḥezkel Landau’s Dagul MeRevava, he concludes that the one who suffers a stroke with loss of function of his left arm would be required to wear tefillin accompanied by the requisite blessing.

Chapter 25[19] Anatomical Dissection

The topic of discussion for this chapter is anatomical dissection.

This appears to be a narrative bibliography of sorts. Della Volta cites a reference to a passage “at the end of Yoreh De’ah.” The halakha[20] to which he refers is:

אין מפרקין את העצמות ולא מפסיקין את הגידים

One must not separate the bones of the body, nor sever the gidim (however these are to be defined, possibly includes veins, arteries, nerves, and tendons).[21]

This halakha is in the context of a discussion on likut atzamot, collecting the bones for reburial after initial temporary burial, often in caves or kukhin (niches).[22] This halakha is not typically invoked in contemporary halakhic discussions about the prohibition of autopsy. The now famous teshuva of the Noda biYehuda on autopsy (Tinyana Y.D., 210) had already been published in 1776, but Della Volta does not appear to have been familiar with it.

While the Hebrew source seems to oppose dissection, the other sources marshalled appear to be supportive. In his discussion on the use of tefillin in a case of stroke, there is no mention of secular or medical sources, as they would be noncontributory. In a discussion on the value of dissection, such material would certainly be relevant. He cites, for example, the preface to a work on pathology by Christoforo Conradi which lauds the educational benefits of anatomical dissection.[23]

Della Volta cites from a number of additional medical sources, including Biblioteca Medica Browniana Germanica.

Of particular interest is his reference to another Jewish source:

Here he refers to the work of Benzion Raphael Kohen (Benedetto) Frizzi titled, Dissertazione di Polizia Medica sul Pentateuco (Pavia, 1787–1790), which is a thematic analysis of medicine and public health in the Torah and Jewish tradition.[24]

This volume, published in 1789, is one of six such dissertations written by Frizzi over four years. The exact passage referenced by Della Volta begins below:

This may be one of the earliest, if not the earliest, Jewish references to the works of Frizzi.

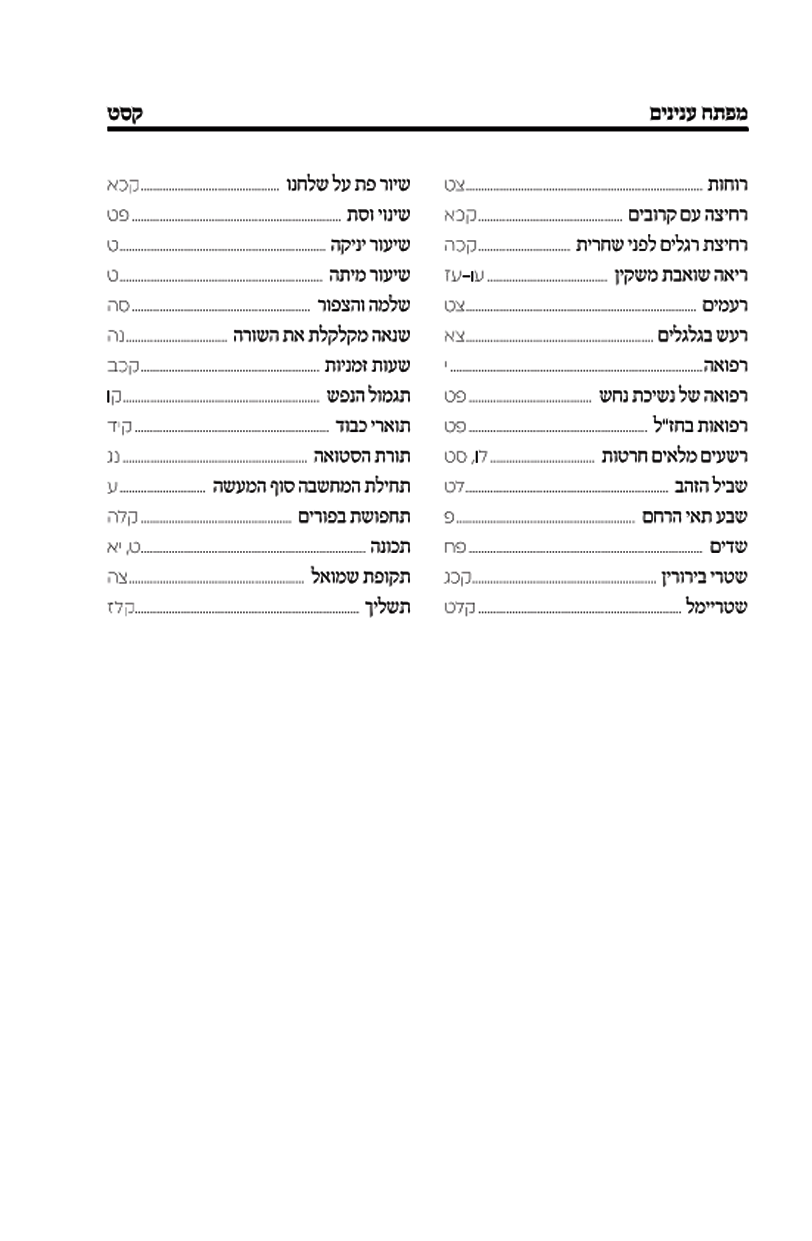

Frizzi subsequently expanded his research to produce a little-known work in Hebrew of over a thousand pages, P’tah Einayim (Leghorn, 1815–25), addressing the medical and scientific aspects of the Talmud.[25] In a section from this work, not cited by Della Volta, Frizzi addresses another rabbinic passage which is conspicuously omitted from modern halakhic discussions on autopsy.

Frizzi focuses on the statement, “Didn’t Rav Yitzḥak say: The gnawing of maggots is as excruciating to the dead as the stab of a needle is to the flesh of the living.”[26] While this passage and its corollary rabbinic passages has received ample treatment,[27] Frizzi’s lesser-known interpretation is exceptional:

Recent medical research, by the likes of Albrecht Haller and Luigi Galvini, who explored bioelectricity (or animal electricity) and muscle irritability, even after death,[28] led him to consider the possibility that this statement was meant literally, i.e., the corpse experiences physiological pain. At least one posek of his day cited Frizzi’s interpretation as a reason to prohibit autopsy.[29]

A most remarkable aspect of this entry is the signature of the author.

הרופא ולא לו הצעיר וזעיר(?) שמואל חי מלאוולטה

I recently completed an article about the various interpretations of a rarely used physician epithet, “A Physician, and Not for Himself,” after serendipitously discovering its use in a manuscript.[30] After an extensive, though not exhaustive, search, I was able to identify only nine physicians throughout history who have used this epithet. As hashgaḥah would have it, we now know of at least ten.[31] Its use here, however, does not shed any further light on the meaning of this expression.

Chapters 38,[32] 116[33] and 128[34] Bathhouse Insemination

These three chapters discuss one who is born sine concubito, through artificial insemination, or as in the Talmudic case, through bathhouse insemination.[35]

(Chapter 128)

Della Volta is equally versed in both the halakhic and contemporary medical literature. While his then current medical references, such as Commentarii Medici by Brugnatelli and Brera,[36] may be unfamiliar to us, his halakhic sources ring remarkably familiar. Amongst others, he cites from Ḥida,[37] Mishneh LiMelekh, Maharil regarding Ben Sira, Rashbetz, R. Yaakov Emden, R’ Yitzḥak Lampronti’s Paḥad Yitzḥak, Ḥelkat Meḥokek, as well as Frizzi, including Petaḥ Einayim.[38] This reads like a contemporary article on artificial insemination by Dr. Rosner or Rabbi Bleich, though for Della Volta this was a purely hypothetical halakhic question. It would only be in the late 19thearly 20th century that this would take on practical halakhic relevance with the development of therapeutic artificial insemination. Indeed, the very same sources can be found in today’s discussions. In my historical discussion of artificial insemination, I discuss all the aforementioned sources, including Frizzi.

A casual glance at the remainder of Dan Yadin reveals countless detailed references to medical, secular, and Jewish sources, replete with chapter and verse. Della Volta was clearly a doctor of the book. In fact, he wrote for the journal Otzar Nehmad, corresponded with the likes of Shmuel David Luzzatto, Joseph Almanzi and Lelio Della Torre,[39] and contributed an introduction to Shlomo Norzi’s Minhat Shai. But his bibliophilia did not stop at reading and writing; he ventured into the world of book and manuscript acquisition, amassing an impressive library by the end of his life. Della Volta’s name would not appear on a list of prominent Jewish book collectors, nor even as an afterthought for that matter. Names such as Azulai, Oppenheim,[40] Almanzi or Strashun[41] are more likely to come to mind. Yet, his library caught the eye of some of the greatest Jewish scholars of his day, a virtual who’s who of Jewish biobibliographers, including Marco Mortara, Moritz Steinschneider, Shmuel David Luzzatto (Shadal) and Moshe Soave.

Marco Mortara (1815-1894) was one of Shadal’s prize students at the Rabbinical Seminary of Padua and later served as the Chief Rabbi of Mantua.[42] Mortara became a renowned scholar and bibliographer[43] and would go on to collaborate with Steinschneider for decades. Their very first correspondence was about the biographical details of Della Volta. Della Volta’s library was of great interest to Steinschneider, as evidenced by the multiple correspondences to both Shadal and Soave on this matter. It is only from the letters of Shadal to Steinschneider that we learn how Mortara had acquired Della Volta’s library, which by that time contained some 130 unique manuscripts that bibliophiles across Europe had unsuccessfully tried to purchase. How Mortara came to possess such a valuable library, especially given his financial situation, whether by inheritance or monetary acquisition, is a matter of debate.[44] In any case, this represents the first stamp in our passport, but a brief journey for Della Volta’s diploma within the city limits of Mantua. Della Volta’s library and diploma, at least for now, remained in his hometown.

It is in the Summer of 1877 that the second journey of our graduate’s diploma commenced. As librarian of the Budapest Rabbinical Seminary, David Kaufman, a prodigious historian and bibliophile, had acquired the collection of Lelio Della Torre, an Italian Jewish scholar. While in Italy making arrangements for the transfer of the library, he made the acquaintance of Mortara. Kaufmann was well aware of the extent and value of Mortara’s collection, and that it included Della Volta’s library as well.[45] Kaufmann and Mortara would correspond for some time thereafter.

When Mortara died in 1894, you can well imagine the great interest in his collection, which the family was motivated to sell. A number of individuals and institutions, including Kaufmann, were vying for the opportunity, but family and logistical issues delayed the process, not the least of which being the absence of a comprehensive catalogue of the holdings. It would ultimately be David Kaufmann who would walk away with the treasure, his success partially attributed to his earlier visit in 1877, his previous familiarity with the collection, and his continued contact with Mortara and his family.

The transfer of this library from Mantua to Budapest, where it arrived in February 1896, was apparently no small feat, with some of the Mortara collection somehow finding their way into non-Kaufmann hands.[46] Yet, it represents the second entry in our passport and longest journey for our diploma.

Alas, Kaufmann would die only three years after acquiring the Mortara collection. Would Della Volta’s collection now be transferred to the hands of a new scholar in yet another country, perhaps America or Israel? Fortunate for our diploma, its third and final journey would again be only a brief intracity trek, akin to its earlier trip in Mantua. Kaufmann bequeathed his collection to the Hungarian Academy of Science, where it remains to this day.

Fortunate for scholars unable to journey to Hungary, reference, and often digitized copies, of items in the Kaufmann collection can be found on the National Library of Israel website.

I doubt that Della Volta would have envisioned that the final resting place for his collection would be in Budapest, but nor would he have imagined a Jewish doctor in Woodmere writing about, of all the valuable items in his library (including his original compositions), his medical diploma.

[1] See Edward Reichman, “Confessions of a Would-be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuvia Ha-Rofeh) and Other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,” in Kenneth Collins and Samuel Kottek, eds., Ma’ase Tuviya (Venice, 1708): Tuviya Cohen on Medicine and Science (Jerusalem: Muriel and Philip Berman Medical Library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2021).

[2] Harry Friedenwald Collection in the National Library in Israel.

[3] G. Baldissin Molli, L. Sitran Rea, and E. Veronese Ceseracciu, Diplomi di Laurea all’Università di Padova (1504–1806) (Padova: Università degli studi di Padova, 1998), 251.

[4] Baldissin Molli, op. cit., 255.

[5] University of Padua Archives, Ms. V. 106.

[6] This was a period of transitioning away from the smaller diploma booklet to larger size and less illustrated documents. See Baldissin Molli, op. cit.

[7] For further discussion, see E. Reichman, “The ‘Doctored’ Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menaseh ben Israel: Forgery of ‘For Jewry’,” Seforim Blog, March 23, 2021.

[8] I have only identified one extant diploma from a Jewish medical graduate of the University of Siena. For discussion of this graduate, as well as a picture of his diploma, see E. Reichman, “The Physicians of the Rome Plague of 1656, Yaakov Zahalon and Hananiah Modigliano,” Seforim Blog, February 19, 2021.

[9] The religious references are in any case removed from this standard Ferrara diploma, but neither do we find the often-seen identifier for Jewish students, Hebreus.

[10] Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Studiensaal Archive, HA, Pergamenturkunden, Or. Perg. 1649 Juli 09. On this diploma, see Moritz Stern, “Das Doktordiplom des Frankfurter Judenarztes Isaak Hellen (1650),” Zeitschrift fur die Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland 3 (1889), 252-255.

[11] https://footprints.ctl.columbia.edu.

[12] The most expansive biobibliographical reference I have found is in Asher Salah, La Republique des Lettres: Rabbins, Ecrivains et Medecins, Juifs en Italie au XVIIIe Siecle (Brill: Leiden, 2007), 661-662. See also 428.

[13] NLI 990001918010205171.

[14] Folios 27-28 of the manuscript.

[15] On Portaleone, see H. A. Savitz, “Abraham Portaleone: Italian Physician, Erudite Scholar and Author, 1542-1612,” Panminerva Medica 8:12 (December, 1966), 493-5; S. Kottek, “Abraham Portaleone: Italian Jewish Physician of the Renaissance Period – His Life and His Will, Reflections on Early Burial,” Koroth 8:7-8 (August, 1983), 269-77; idem., “Jews Between Profane and Sacred Science: The Case of Abraham Portaleone,” in J. Helm and A. Winkelmann (eds.), Religious Confessions and the Sciences in the Sixteenth Century (Brill, 2001). For a full text of his will, see D. Kaufman, “Testament of Abraham Sommo Portaleone,” Jewish Quarterly Review 4:2 (January 1892), 333-41; A. Berns, The Bible and Natural Philosophy in Renaissance Italy (Cambridge University Press, 2014). Shadal discovered a remarkable letter by Portaleone recounting his brush with death on February 25, 1576, when he escaped unscathed from a vicious attack. Although his cloak was perforated in sixteen places from the perpetrator’s sword, miraculously no blood was drawn. See Y. Blumenfeld, Otzar Nehmad 3 (Vienna, 1860), 140-1.

[16] For a copy of the text of his diploma, see V. Colorni, Judaica Minora (University of Ferrara Press, 1983), 487-9.

[17] This work has recently been reissued in an expansive, copiously footnoted edition with introductory essays and biography. See Y. Katan and D. Gerber (eds.), Shiltei Ha-Gibborim (Makhon Yerushalayim, 5770).

[18] 1:3.

[19] Folio 78 of the manuscript.

[20] Y. D. 403:6.

[21] For a discussion on the history of anatomical dissection in rabbinic literature, including the identification of the 248 evarim, as well as the gidim, see Edward Reichman, The Anatomy of Jewish Law: A Fresh Dissection of the Relationship Between Medicine, Medical History and Rabbinic Literature (OU Press, YU Press, Maggid Press: Jerusalem, 2021), forthcoming.

[22] For a discussion on the history of Jewish burial practices in antiquity and the use of kukhin, see Patricia Robinson, The Conception of Death in Judaism in the Hellenistic and Early Roman Period (Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1978).

[23] I thank Filippo Valle for his assistance in both translation and research for this passage.

[24] See Ephraim Nissan, Benedetto Frizzi, a Physician, Medical Editor, Jewish Apologist, and Johann Peter Frank’s Pupil, Who Interpreted Moses’ Law as a Sanitary Code in Line with Frank’s Theory of Public Hygiene,” Korot 25 (2019-2020), 259-293.

[25] On Frizzi, see S. Simonsohn, History of the Jews in the Duchy of Mantua (Kiryat Sefer, 1977), 649, n. 226; Friedenwald, op. cit., 115; L. Dubin, “Medicine as Enlightenment Cure: Benedetto Frizzi, Physician to Eighteenth-Century Italian Jewish Society,” Jewish History 26(2012), 201–221. On his work, see B. Dinaburg, “Ben Tzion Hakohen Frizzi and His Work Petaĥ Einayim,” (Hebrew) Tarbitz 20(1948/49), 241–64. For an exchange between Frizzi and Shadal about a work of the latter, see Moshe Shulweiss, “Shmuel Dovid Luzzatto, Pirkei Hayyim,” (Hebrew) Talpiyot 5:1-2 (Tevet, 5711), 41. For a reference to Frizzi dining with Hida, see Aron Freiman, ed., Ma’agal Tov haShalem of Rabbi Hayyim Yosef David Azulai (Mekize Nirdamin: Jerusalem), 94.

[26] Shabbat 13b. Full translation of passage (from Sefaria): Alternatively: The flesh of a dead person does not feel the scalpel [izemel] cutting into him, and we, too, are in such a difficult situation that we no longer feel the pains and troubles. With regard to the last analogy, the Gemara asks: Is that so? Didn’t Rav Yitzḥak say: The gnawing of maggots is as excruciating to the dead as the stab of a needle is to the flesh of the living, as it is stated with regard to the dead: “But his flesh shall hurt him, and his soul mourns over him”(Job 14:22)? Rather, say and explain the matter: The dead flesh in parts of the body of the living person that are insensitive to pain does not feel the scalpel that cuts him.

[27] I am presently working on a more expansive analysis of this passage titled, “On Pain of Death: Postmortem Pain Perception in Rabbinic Literature.”

[28] See, for example, Hubert Steinke, Irritating Experiments: Haller’s Concept and the European Controversy on Irritability and Sensibility, 1750-90, Vol. 76 of Clio Medica, Wellcome Series in the History of Medicine (Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, 2005); Dominique Boury, “Irritability and Sensibility: Key Concepts in Assessing the Medical Doctrines of Haller and Bordeu,” Science in Context 21:4 (2008), 521-535.

[29] R’ David Zacuto D’Modena (d. 1865). This manuscript responsum by D’Modena on autopsy was published by Yitzhak Raphael, “Two Responsa on Autopsy,” (Hebrew) Sinai 100 (1987), 737-748.

[30] See E. Reichman, “’A Physician, and Not for Himself’: Revisiting a Rare Jewish Physician Epithet That Should So Remain,” forthcoming. For earlier discussions of this expression, see Joshua O. Leibowitz, “‘Physician and Not for Himself,’ An Unusual Hebrew Medical Epithet,” Koroth 7:7-8 (December, 1978), CXXIX- CXXXIII; Meir Benayahu, “Physician and Not for Himself,” Koroth 7:9-10 (November, 1979), 725-725; Abraham Ohry and Amihai Levi, “Physician and Not for Himself,” Koroth 9:3-4 (1986), 82-83 (Hebrew) and 399*-401* (English).

[31] Della Volta does not appear to use this signature elsewhere throughout this manuscript, and I only found it in chapter 25. A review of his other manuscripts, which I did not do, would be instructive.

[32] Folio 89 of the manuscript.

[33] Folio 122 of the manuscript.

[34] Folio 126 of the manuscript.

[35] On bathhouse insemination and the story of Ben Sira in rabbinic literature, see E. Reichman, “The Rabbinic Conception of Conception: An Exercise in Fertility,” Tradition 31:1 (Fall 1996), 33-63, reprinted with additions and revisions in Reichman, The Anatomy of Jewish Law, op. cit.

[36] An eight-volume work published between 1796-1799.

[37] Ya’ir Ozen, En Zokher, ma’areḥet aleph, n. 93 and Birkei Yosef E.H. 1:14.

[38] Volume 4 (I. Costa: Livorno, 1879), 57b-58a.

[39] See NLI system n. 990001918190205171, pgs. 45, 98, and 116. This is a collection of his letters to Italian maskilim.

[40] See Joshua Teplitsky, Prince of the Press (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2019).

[41] See Dan Rabinowitz, The Lost Library: The Legacy of Vilna’s Strashun Library in the Aftermath of the Holocaust (Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry, 2018).

[42] On Mortara, see Asher Salah, “The Intellectual Networks of Rabbi Marco Mortara (1815–1894): An Italian “Wissenschaftler des Judentums,” in Paul Mendes-Flohr, et. al. eds, Jewish Historiography Between Past and Present, Studia Judaica, Band 102 (2019), 59-76. On his library, see idem, “La Biblioteca di Marco Mortara,” in Mauro Perani and Ermanno Finzi, eds., Nuovi Studi in Onore di Marco Mortara nel Secondo Centenario della Nascita (Firenze: Giuntina, 2016), 149-168. What follows is drawn primarily from these works.

[43] In addition to countless articles in the periodicals of his day, Mortara is known for his Catalogo della Biblioteca della Communita Ebraica de Montova and Indice Alfabetico dei Rabbini e Scrittori Israeliti di Cose Guidaiche in Italia.

[44] See Salah, “La Biblioteca,” op. cit., 152.

[45] See Salah, “La Biblioteca,” op. cit., 155.

[46] See Salah, “La Biblioteca,” op. cit., 157. Somewhere along the way, Harry Friedenwald acquired a book that was part of the Della Volta library, a prayer book according to the German rite published by the physician and Padua graduate Eliezer Solomon d’Italia. Della Volta added a 9-page manuscript to the copy which includes a history of the d’Italia family chronicles. See H. Friedenwald, Jewish Luminaries in Medical History (Johns Hopkins Press, 1946), 88.