The First Artichoke Controversy of 2012

By Leor Jacobi

Recently a

kashrut controversy surrounding traditional Italian fried artichokes has received major media coverage in the New York Times and the

Seforim Blog (

twice, in chronological order, not order of importance). In order to prove the antiquity of Jewish artichoke consumption, depictions of artichokes in medieval illuminated haggadot have been adduced. These were the topic of a lesser-known artichoke controversy in 2012 here in the

comments section of the Seforim Blog, which can be as nasty and difficult to find as artichoke bugs.

The Controversy: Do Catalonian medieval Haggadot portray maror as an artichoke? Were artichokes actually consumed in fulfillment of the rabbinic requirement to consume bitter herbs found in the Mishnah and Tosefta?

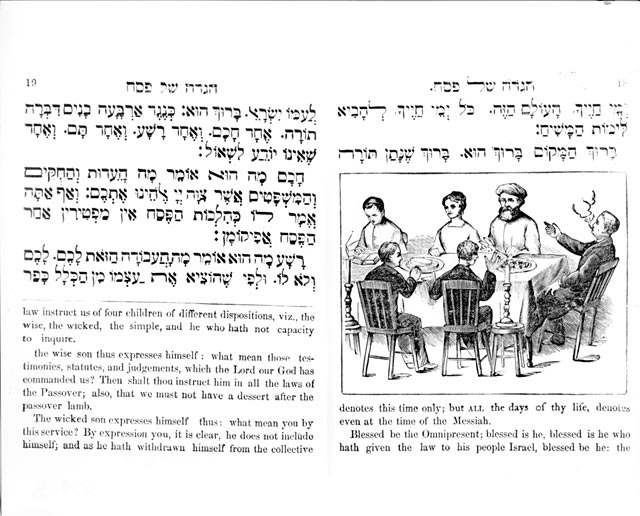

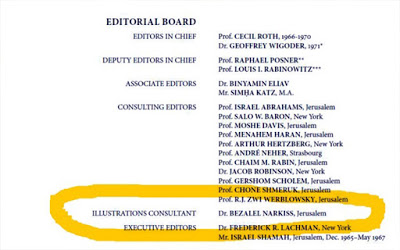

“Brother Haggadah”, BL Oriental 1404, f. 18

Here’s the story behind the scenes as it occurred in real time, during the Pessah season of 2012. I was scheduled to deliver

a talk on chrayn at a rabbinic conference on the Hebrew language organized by Yitzhak Frank on April 10, Chol ha-Moed Pessah. In the course of some late preparatory research (= Googling) on April 5 (13 Nissan, the day of

bedikat chametz) I came across a

fascinating responsum on

maror by David Golinkin that had just been published on April 2, 2012. Struck by the reliance on visual evidence from illustrated manuscripts in establishing a medieval custom to consume artichokes as

maror, I sent the post to Marc Michael Epstein of Vassar College for comment. Within an hour he replied:

I don’t believe the Sephardic mss show an artichoke, rather they depict an entire head of romaine lettuce. The way to prove or disprove this would be to compare contemporary or roughly contemporary botanical mss.

I immediately began “intensive research” (= more Googling) and discovered that the artichoke question was (probably first)

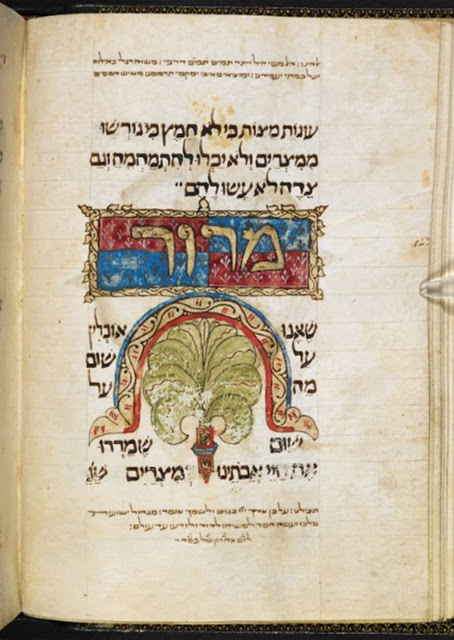

posed by Yoel Finkelman and his parents in 2005. Significantly, they already collected the three examples cited by Golinkin: the

Rylands,

Brother, and

Sarajevo Haggadot. Finkelman states that his father circulated the query widely.

Rylands Haggadah, 1988 facsimile edition, f. 31v

The next day, April 6, Erev Pessah, I emailed Golinkin directly, requesting sources for his identifications. He replied on the same day that artichokes are definitely depicted in the three illuminated haggadot and that artichokes were probably identified as one of the five plant species mentioned in the Mishnah (Pesahim 2:6). Indeed, in Golinkin’s own post of April 2:

Rabbi Natan ben Yehiel of Rome (1035-ca. 1110) says in his Talmudic dictionary (ed. Kohut, Vol. 8, p. 245) that tamkha is cardo, which is cardoon. Prof. Feliks says that this is carduus argentatus or silver thistle, while Dr. Schaffer says that it is cynara cardunculus or artichoke thistle.

So, textual and visual evidence interlock to support the conclusion that artichokes were used as Maror. However, the textual evidence is weak.

Sefer Ha’arukh is a dictionary, not a responsum, a legal code or a gloss to one, like

Hagahot Maimoniyot which identifies

tamkha as horseradish – chrayn, associated with an actual custom. The definition of

Ha’arukh is not a singular, definitive identification (

yesh ‘omrim:

marrobio, another species, also Rashi’s identification), and according to Prof. Jehudah Feliks cardo does not describe artichokes at all.

Opposite this scanty textual evidence stands a mountain of Rabbinic silence. As far as I am aware, nowhere in any codes, Haggadas, commentaries, or anywhere else do we find even a hint that artichokes were ever used as maror. There are limits to what can be learned ex silentio but we are discussing thousands of sources. If artichokes were used, we would expect a mention somewhere.

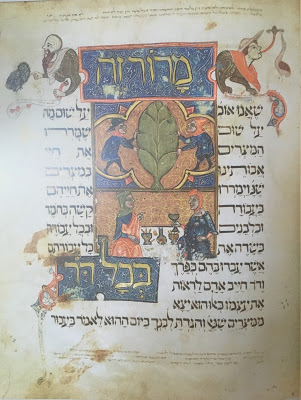

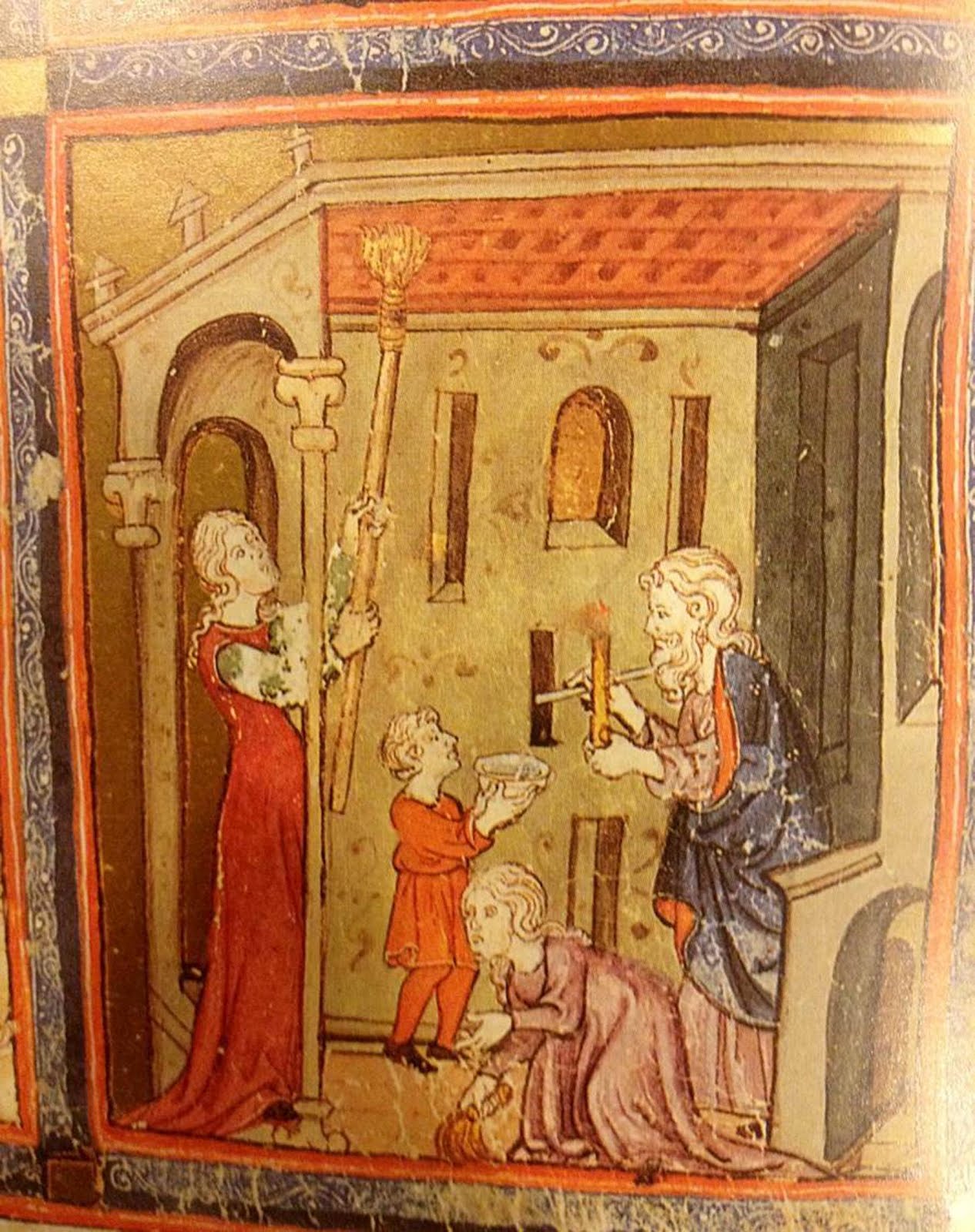

As for the visual information, we have “two witnesses and three witnesses”: The Rylands and Brother Haggadahs should be considered one witness because one is copied from the other. Bezalel Narkiss designated the name “The Brother Haggadah” (along with a lot of other names of Haggadah, most of which have stuck, for better or worse) because it is the “brother” copied from the Rylands Haggadah. According to Katrin Kogman-Appel, the Brother was more likely the original from which the Rylands was copied. For our purposes, the direction of the copying makes no difference. Just as the Rosh and Tur can’t really be counted as two legal authorities, these two sources are reflections of one another. What about the other witness, the Sarajevo Haggadah?

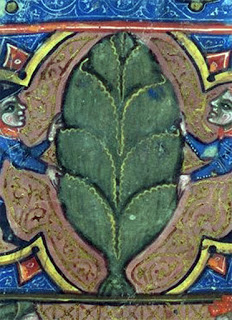

I do not think that there is even a remote possibility that the Sarajevo Haggadah depicts an artichoke:

The leaves are ridged but all species of artichoke leaves are smooth save for the thorn in the middle. An artist whose intention was to depict artichokes would not draw them in this manner. Moreover, Epstein, (in personal correspondence) adds that the “artichoke” leaves are “veined” like lettuce leaves, and bound together with a cord at the base.

Israeli Artichoke, Photo: Leor Jacobi, April 20, 2012

The same day, April 6, Erev Pessah, I communicated my skepticism back to Golinkin, especially regarding the depiction in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Golinkin’s April 2 post had already inspired

creative contemporary midrash by April 9 (the truth of which in revealing hidden aspects of the divine plan should be judged independently of the historical claims.) Clearly these progressive folk placed artichokes on their seder plate on seder night, April 6 or 7, 2012, and were already expounding homiletically on the custom they had only learned about on April 2 at the earliest. Epstein notes that this an excellent example in “real time” of a

minhag in development thanks to what he calls “the

heter of the Internet.”

In the Brother to the Rylands Haggadah, marror is depicted as an artichoke, as is in the case with the Sarajevo Haggadah.

Golinkin wasn’t cited but it’s doubtful that his April 2 post is the source — perhaps serendipity. After some discussion in the comments, Marc Epstein wrote:

Rabbosai (and Marasai): A manuscript is NOT a mirror. Jews depict themselves in their art (or commission art that depicts them) not as they were, but as they desired to be seen. Please please please do not engage in the typical Wissenschaft strategy of looking at illuminated manuscripts for “clues to Jewish life in the Middle Ages” or even to Jewish history. What we can learn from them is histoire des Mentalites, but even that takes a lot of work to get to.

Re: the “artichoke”: I don’t believe the Sephardic mss show an artichoke, rather they depict an entire head of romaine lettuce. The way to prove or disprove this would be to compare contemporary or roughly contemporary botanical mss. It may have been “misunderstood” by some illuminators as an artichoke, but not corrected by the recipients of the manuscript because if you are not looking for an artichoke it seems totally absurd that an artichoke would be used as maror, You don’t SEE an artichoke, but a head of Romaine lettuce, no matter how “artichoke-like” it seems to us in 5772.

Also, because a head of Romaine is SHOWN in the haggadah it doesn’t mean that there a head of (possible unchecked-for-bugs) Romaine on the table. Every image is not a snapshot, but a representation — a combination of the real, the general, the ideal and the symbolic. Showing the head is a way of REPRESENTING Romaine — it says, “We use a type of lettuce that grows with leaves together in a head like this.” It does NOT necessarily mean “We use complete heads of Romaine at the Seder, like this.” Do you see the difference? A representation must shorthand its descriptions for clarity: If you showed individual artichoke leaves, for instance, it would be difficult to ascertain that the plant was an artichoke. Artichoke leaves are shaped like baby spinach leaves, though baby spinach is more pliable. If a leaf of that shape was shown, what would distinguish the artichoke leaves? Showing an artichoke in its entire, thistly configuration makes it indisputable that it is an artichoke.

Epstein’s points are compelling. How does one portray lettuce in an illustration? For example, this modern lettuce clip-art isn’t much more lettuce-like than the illustration in the Brother Haggadah:

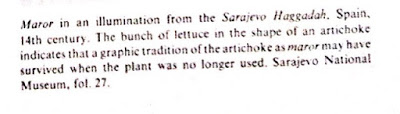

After Pessah, on April 22, I received an additional reply from Golinkin with more sources. The entry for maror in the first edition of Encyclopedia Judaica was written by Jehudah Feliks (pp. 1014-5). The entry includes an image of the maror depiction from the Sarajevo Haggadah with a caption:

According to this astounding caption, lettuce is depicted in the Sarajevo Haggadah but the claim is that it can still be supposed that the artichoke-like shape of the lettuce reflects an old custom of eating artichokes as

maror. This custom had already been lost in the 14th century, but was preserved in the form of illustrations of

maror in haggadot! (We find something similar in the illustrations of maror in the Prague Haggadah. According to

Rav Peles, the custom of pointing at the wife when stating “this bitter[ness/Bitter Herb]” had already disappeared, but was preserved in the caption to the

maror illustration in the Haggadah; see also

here). However, note that above, in Golinkin’s post, Feliks did not identify the

Arukh’s cardo as artichokes. It is not entirely clear that Feliks composed this caption. Bezalel Narkiss served as IIlustrations Consultant on the first edition (sadly most illustrations were cut from the second edition, including this one and the caption).

As Narkiss was then the acknowledged expert in medieval illuminated manuscripts, it stands to reason that he may have either selected the illustration or wrote the caption, either alone or in consultaion with Feliks. In any case, the author(s) of the caption maintain that lettuce is depicted even if the rest of their proposal is extremely speculative.

For the Rylands Haggadah, Golinkin cited the Raphael Loewe facsimile, Steimatzky, 1988: “The bitter herb is intended to be lettuce, despite its artichoke-like compactness.” This pithy source contradicts Golinkin’s identification, and suggests a practical explanation for this lettuce design.

As for the Brother Haggadah, Golinkin wrote that he learned about this from an expert on Jewish art. However, as far as I can tell this expert does not deal primarily with interpretation of medieval art. Theories are tested by evidence. Thus, it remains that if someone wishes to argue that these images depict artichokes the best way to advance the thesis would be by means of comparisons with contemporary illustrations of artichokes, as Marc Epstein advises.

Finally, an image of maror from the Barcelona Haggadah, folio 62, illustrates how creative illustrations of lettuce (?) could get and how dangerous it would be to try to learn history from them as if they were snapshots.

Verso, The scribe left almost the whole of the page for a depiction of the bitter herbs, but the crude illustration we now see was not executed in the Middle Ages, although it may have been based on models from the fourteenth century. The vegetable, commonly portrayed in a highly stylized manner, was no longer understandable to the later artist, and the red holder with which it is sometimes shown seems to have been misunderstood by the artist, who interpreted it as a red crescent.

The post-medieval illustrator here may have utilized haggadah depictions of artichoky lettuce as a model and was probably as bewildered by them as we are. In note 39 Cohen lists the Hispano-Moresque, Graziano, Golden, and Sister Haggadas as displaying maror holders. The matzot in these haggadot look nothing like real matzot, with elaborate color and geometric designs. The entire maror holder could be a design element in this vein, so that the maror is grounded and not floating in space.

Graziano Haggadah

Sister Haggadah

‘Hispano-Moresque’ Haggadah

Golden Haggadah

Epstein adds (personal correspondence) that we should be wary of concluding on the basis of these images that Jews of Medieval Spain had actual red maror holders. They may have developed from an earlier model like the Golden Haggadah, which only meant to portray a reddish-yellow color which develops towards the base:

I certainly hope enterprising Judaica forgers, the creators of “Marrano cups” and such don’t get wind of this, or appraisers, experts and curators will have a whole new wave of fake “authentic” pre-Expulsion Sephardi ritual items to deal with. Indeed Romaine lettuce is most suitable for maror because it generates increasing bitterness the longer one chews the leaves, and the closer one gets to that all-important base. Romaine is appropriate for maror in metaphoric terms: like the servitude in Egypt, which started out as a “public works” project with the full participation even of Pharaoh, and ended up as the most abject of slavery, a torture inflicted exclusively upon the Israelites. When one first begins to chew the leaves Romaine lettuce, one could think one was eating a lovely salad. More chewing, and getting eventually to the lower “spine,” however, makes the experience increasingly bitter. The rabbis understood that unlike the consistent blast of heat one experiences with horseradish and other truly bitter plants, it is in the initially non-bitter, even pleasant, but then the increasing nature of the bitterness of Romaine that the precise metaphor for the Egyptian servitude is experienced.

It is notable that per Kogman Appel’s dating, the Golden Haggadah is earlier (c. 1320) than some of the examples brought above (c. 1350-), and may have served as their model in some sense, including the fact that whatever we are seeing, (whether the “veins” in a single lettuce leaf, or the ruffled leaves in the head when cut open and depicted laterally, like the Chinese cabbage shown below,) gives the leaf/leaves a “spiky” appearance. (If there is a lateral view here, the question, of course, is why such a view was taken. Most authorities prefer whole Romaine leaves for maror, so a view “cutting through” the head might be confusing, although some advocate the consumption of only, or primarily the spines.)

The more I think about it, although links and distinctions have been made between the opening sequence of biblical narrative illuminations in the Golden, Sister and Sarajevo Haggadot and the Rylands/Brother Haggadot, the TEXT illustrations (matzah, maror etc.) may have more mutual influence and cross-influence, and relate also to those in the Barcelona Haggadah and others. Since the GH was earlier than the Sarajevo, Rylands/Brother Haggadot, the image of the maror there, clearly— though stylized—Romaine may have influenced, been misunderstood by the artists of the later ms. In other words, the veiny (or the lateral, or side-viewed, rippling) leaves of Romaine could have been mistaken for the “spiky” leaves of an artichoke and thus been illustrated. (The Sarajevo artist, for instance, depicted the “artichoke” leaves not only as serrated but with “veins” more typical of lettuce.)

The Sarajevo, Rylands/Brother ARTISTS misunderstanding the [veined single lettuce leaf or laterally viewed or cut head of] lettuce in the Golden Haggadah or a similar model, might have thought they were illustrating an artichoke. The PATRONS did not “correct” this because OBVIOUSLY the vegetable could not have been an artichoke as there was no massoret of the use of that vegetable for maror. There for they accepted the “artichoke” of the artists as the “lettuce” of halakhah.

While we can never recover the actual conversation that precipitated the visual result, both consideration of the near-instantaneous creation via “the heter of the Internet” of the minhag of placing artichokes on the seder plate, and the spinning of homiletics around that minhag; and the invention of the “maror holder”are reflections—within our present conversation!—of the kinds of transmission problems ever present in such conversations in any time or place. This whole adventure has, for me, been very important in thinking about artist-patron relationships.

Cohen adds an interesting point (personal correspondence):

I found other manuscripts where there was a blank space where the image of the maror should have been placed, while all the other areas left blank by the scribe contained illustrations. This lead me to believe that the appearance of the maror was sometimes customized based on the minhag of the patron, who for whatever reason never had it added.

These are fascinating questions. The goal of the artists was to produce art which resonated with their patrons symbolically and aesthetically. By misinterpreting these images as snapshots of historical reality, we can invent artichokes and maror holders. One could just as well conclude that it was customary to

only sit on one side of the Seder table!

Fast forward to May, 2018, we find ourselves embroiled in a new artichoke controversy and the

Seforim Blog is back with artichokes in the Haggadah. This is a fascinating little post on

kashrut and custom, but nothing about ancient or medieval practices can be proven from these sources. A

follow-up post based on textual sources by Susan Weingarten, an expert on foods in antiquity (and incidentally, the sister of Elihu Shanun, who also spoke at the

rabbinic conference on April 10, 2012 which started us off) provides a much more reliable textual path towards establishing the antiquity of artichoke consumption.

In summary, there is no evidence that Jews ever ate artichokes to fulfill the obligation of consuming maror on the Passover Eve. Maybe b’shas hadahak, but who knows? The textual evidence and visual evidence don’t support each other to advance a radical historical claim. However, artichokes are delicious and, if clean, Kosher for Pessah. Jews very likely did consume them historically wherever they were found.

Thanks to: Marc Epstein, David Golinkin, Evelyn Cohen, Sara Offenberg, Moshe Glass, and Jean Guetta. I also wish to acknowledge the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture for their support.

As detailed in chapter 8 of Epstein’s Medieval Haggadah, the early 14th Century Golden Haggadah is perhaps the most female-centric Haggadah and may have been commissioned for a woman. That manuscript emphasizes the unique, positive, and critical role women played in the Exodus narrative. Although it also depicts the practice of overzealous cleaning with a woman sweeping the ceiling. The 1430 Darmstadt Haggadah has a full-page illumination of women teachers, but its connection to the text is opaque. Finally, we

As detailed in chapter 8 of Epstein’s Medieval Haggadah, the early 14th Century Golden Haggadah is perhaps the most female-centric Haggadah and may have been commissioned for a woman. That manuscript emphasizes the unique, positive, and critical role women played in the Exodus narrative. Although it also depicts the practice of overzealous cleaning with a woman sweeping the ceiling. The 1430 Darmstadt Haggadah has a full-page illumination of women teachers, but its connection to the text is opaque. Finally, we

After completing the Haggadah, Moss was asked to reproduce it, and, with Levy’s permission, produced, what the former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Bornstein, described as one of the greatest examples of 20th-century printing. The reproduction, on vellum, nearly perfectly replicates the handmade one. This edition was limited to 500 copies, all of which were sold. From time to time, these copies appear at auction and are offered by private dealers, a recent copy sold for $35,000. President Regan presented one of these copies to the former President of Israel, Chaim Herzog, when he visited the White House in 1987. While that is out of reach for many, this version is housed at many libraries, and if one is in Israel, one can visit Moss at his workshop in the artist colony in Jerusalem, where he continues to produce exceptional works of Judaica and view the reproduction. There is also a highly accurate reproduction, on paper that is

After completing the Haggadah, Moss was asked to reproduce it, and, with Levy’s permission, produced, what the former Librarian of Congress, Daniel Bornstein, described as one of the greatest examples of 20th-century printing. The reproduction, on vellum, nearly perfectly replicates the handmade one. This edition was limited to 500 copies, all of which were sold. From time to time, these copies appear at auction and are offered by private dealers, a recent copy sold for $35,000. President Regan presented one of these copies to the former President of Israel, Chaim Herzog, when he visited the White House in 1987. While that is out of reach for many, this version is housed at many libraries, and if one is in Israel, one can visit Moss at his workshop in the artist colony in Jerusalem, where he continues to produce exceptional works of Judaica and view the reproduction. There is also a highly accurate reproduction, on paper that is