R. Yudel Rosenberg, R. Mordechai Elefant, and Sexual

R. Yudel Rosenberg, R. Mordechai Elefant, and Sexual Abuse

Marc B. Shapiro

1. Many readers of the Seforim Blog are aware of R. Yudel Rosenberg, the fascinating talmid chacham and posek who for some reason was also drawn to forgeries. Ira Robinson has recently authored a complete biography of Rosenberg, A Kabbalist in Montreal: The Life and Times of Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg. This wonderful book is certainly deserving of a complete review on the Seforim Blog, but here I would just like to comment on a criticism of me.

On p. 219 Robinson discusses the letter of R. Hayyim Hezekiah Medini that Rosenberg included in his Sha’arei Zohar Torah.

The letter of Rabbi Medini as published by Yudel Rosenberg has been challenged as a forgery by Rabbi Yaakov Hayyim Sofer, David Zvi Hillman, and Marc B. Shapiro on the grounds that some linguistic elements of the letter are foreign to Rabbi Medini’s style and may well have come from the pen of Rabbi Rosenberg.

In the note to this passage, Robinson refers to my Seforim Blog post here, where in addition to mentioning the points made by R. Sofer,[1] I write:

Let me also add that the way Medini (=Rosenberg) concludes the forged haskamah is not like any of his other letters, which are included in Iggerot Sedei Hemed (Bnei Brak, 2006). In the authentic letters, before his name Medini always adds הצב”י or הצעיר, which he does not do in the forged haskamah. In his authentic letters, he also never closes them by adding to his name רב ומו”ץ בעיר הקדש חברון. Therefore, there can be no doubt that the letter of approbation sent by Medini to Rosenberg is simply another one of the latter’s forgeries.

Robinson states (p. 219 n. 25):

On one of his points Shapiro is mistaken. He wrote in his blog: “In the authentic letters, before his name Medini always adds ha-tsa’ir, which he does not do in the forged haskamah.” In Yudel Rosenberg’s work, the Medini letter does close with yedido ha-tsair.

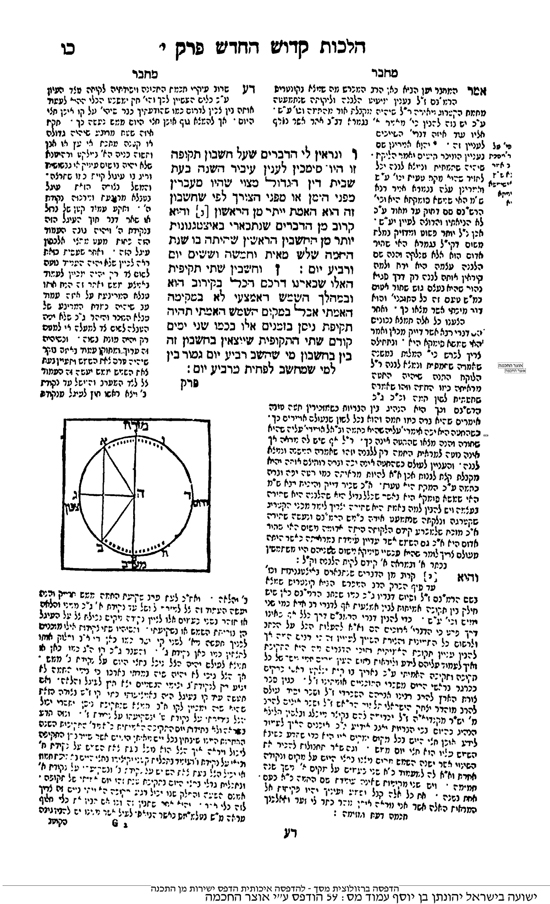

Here is the haskamah, and indeed Robinson is correct that הצעיר appears. I can’t explain why I wrote otherwise.[2]

Since we are discussing the forged haskamah, let me add two additional points relating to the final lines. I looked through all the letters in Iggerot Sedei Hemed and in none of them does this expression appear:

כנפשו הטהורה וכנפש ידידו

Furthermore, R. Medini always adds הי“ו or less commonly ס“ט after his name. Both of these are missing here.

While on the topic of forgeries, let me mention something else. In my post here I deal with the notorious forger, Chaim Bloch. One of the forgeries I mention is his creation of an alternate version of שפוך חמתך in the Passover Haggadah. In Bloch’s forgery, instead of “Pour out Your rage upon the nations that do not know You,” followed by more lines beseeching God to destroy the wicked ones, a more universalist formulation is found that begins with שפוך אהבתך. This forgery, which Bloch claims is from a 1561 Worms manuscript, reads as follows:

Pour out Your love on the nations who have known You and on the kingdoms who call upon Your name. For they show loving-kindness to the seed of Jacob, and they defend Your people Israel from those Who would devour them alive. May they live to see the sukkah of peace spread over Your chosen ones, and to participate in the joy of Your nations.

This translation is taken from R. Jonathan Sacks’ Haggadah (The Applebaum Edition), p. 120. Unfortunately, Sacks did not know about the history of Bloch and thought he was dealing with an authentic text. Sacks introduces the phony prayer as follows:

In one manuscript from Worms, 1521, there is a unique addition to the Haggada alongside “Pour out Your rage.” It is a prayer of thanks for the righteous gentiles throughout history who, rather than persecuting Jews, befriended them and protected them at times of danger.

3. Readers of the Seforim Blog might recall that on a few occasions I cited passages from the memoir of the late R. Mordechai Elefant, Rosh Yeshiva of Itri and builder of a vast Torah empire. These were the first times that passages from the memoir that he dictated appeared in print. I was then one of the few people who had a copy of the memoir, and a number of readers can attest that I did not agree to share it with them because I did not have permission from the person who gave it to me. Subsequently, Mishpacha got a copy of it and published some selected (and “touched up”) portions.[3]

In September 2019, R. Pini Dunner[4] published the memoir and you can view it here (Although this site says May 1, 2013, in reality Dunner only uploaded it in 2019.)

Dunner writes:

Rabbi Elefant’s candid memoirs are startling, not just because they reveal much that one would hardly have expected from a top-tier Rosh Yeshiva, but even more because of the very frank revelations he willingly shared regarding the background to his extraordinary life.

I distinctly recall his many sardonic observations about life and people; he was a true iconoclast who had clearly never read the memo about how senior public servants should express themselves, and particularly rabbis. At the same time, he was an extraordinary scholar, who could lecture on any Talmudic topic, without prior warning, to discerning peers and students, dazzling them with both his vast knowledge and his keen intellect.

Those who examine the Elefant memoir will come away shocked that the author was a leading rosh yeshiva. R. Aharon Rakeffet’s response after completing the memoir was that R. Elefant was “fifty percent gadol, fifty percent gangster.”[5] One thing is sure: R. Elefant was one of the most fascinating Torah scholars in recent memory, and there really was no one like him.

Anyone who reads the memoir must wonder why R. Elefant would have wanted himself to be remembered in the way the memoir describes. Certainly, no one whose only exposure to R. Elefant is through his Torah works could imagine the author’s colorful life. In fact, in R. Elefant’s posthumously published Mi-Zahav Mordechai he is described on the title page as שר התורה הגאון האמיתי.

R. Elefant was obviously an unusual person, and as with other writers of memoirs in rabbinic history (e.g., R. Leon Modena, R. Jacob Emden, R. Elijah David Rabinowitz-Teomim), he was an independent thinker who did not believe in following the herd. R. Elefant, as with all memoir writers, wanted us to learn about his experiences and views, things we would not know about if we only looked at his yeshiva persona.

I asked R. Nathan Kamenetsky about R. Elefant after I read the memoir, and I gave R. Kamenetsky a copy of it. (R. Kamenetsky worked closely with R. Elefant in Itri). But I did not know R. Elefant, so anything I suggest will be speculation.

When I finished reading the memoir, and was wondering why R. Elefant would want all this unusual information made public, I thought of two possible reasons. The first is pride, to show that one can be a talmudic scholar—and R. Elefant was an authentically great one—and at the same time be “with it”, that is, to be able to travel around the world and have relationships with all sorts of unusual people. Looking at matters this way, the memoir can perhaps be seen as subversive, in that although R. Elefant lived in one world, and had great respect for the rabbis of that world, he also happily lived in another world and wanted to show people how he did it.

The other possibility I thought of is that R. Elefant actually felt guilty about how he lived his life, and the memoir was his way of making matters right, as it were. He was a rosh yeshiva and was therefore given great respect. He was also close to a number of gedolei Yisrael. Perhaps R. Elefant felt uncomfortable in his role, where he was regarded as a שר התורה and a גאון אמיתי, since unlike the other roshei yeshiva and gedolim, his life was not one of “only Torah.” Is it possible that R. Elefant was putting it all out there to set the record straight, that is, to let people know who he really was, because in the end he felt guilty that he was placed in the same category as other roshei yeshiva? Could it be that R. Elefant, who had so many interests and couldn’t be happy spending his life entirely in the beit midrash, felt guilty being compared to the roshei yeshiva and gedolim whose entire lives were focused only on Torah study and spiritual improvement? I can’t help but think that if R. Elefant had children, and was busy raising them, he wouldn’t have had his wanderlust and need for adventure.

R. Elefant himself tells us that in addition to his “lamdan side,” he also has a “shaygetz (irreligious) side” (p. 40). I cannot imagine any other rosh yeshiva saying such a thing about himself. R. Elefant’s “shaygetz side” was not something that most would have known about had he not revealed it, and it is this side of him that people have found shocking. Obviously, R. Elefant knew they would find it shocking, yet he still wished to make it public. My sense is that he was a man of truth, and did not want to pretend. He wanted people to know what he was about, with all of his complexity.

I think it is very telling that after mentioning his “shaygetz side,” R. Elefant adds, “Thank G-d that side of me didn’t manifest itself in my students.” This line shows that, at the end of the day, R. Elefant was not very proud of this side of him, which I think lends credence to my suggestion that the memoir was his way of setting the record straight so that the world not think of him as someone he was not. (A close student of R. Elefant told me he liked this suggestion.) Also noteworthy is that right at the beginning of the memoir, R. Elefant states: “But I don’t kid myself. I know I’m not a spiritual model for my students, nor do I ever make out that I am.”

Even if I am wrong in discerning R. Elefant’s ultimate motivation, memoirs by their nature provoke thoughts in the reader, and the two suggestions I mention are what the memoir brought to my mind.

There are those who knew R. Elefant who believe that one must distinguish between his younger days, when he was completely engrossed in Torah study, and later in life when he realized that he had a knack for raising money. It was then that he started traveling the world and hanging out with celebrities, politicians, and other colorful characters. Some will regard this as a limud zekhut for the entire bizarre and eye-opening memoir. Others will probably say that while R. Elefant raised a lot of money and built a Torah empire, the toll it took on him, as seen in how he chose to portray himself in his own memoir, shows that it was not worth it.

The copy of the memoir that Dunner placed online has become internationally famous, and you have to love the title he gave it: “An Elephant Never Forgets”. Yet Dunner’s copy is missing the first page, so let me provide it now.

In Dunner’s copy the handwriting on p. 59 can’t be read. Here are pages 58-59 from my copy so you can see the passage in its entirety.

The first thing to note is that R. Elefant’s claim that Saul Lieberman felt that he should have been made chief rabbi, and because he didn’t get this he went to JTS, is completely mistaken (as is much else in the memoir). R. Kook died in 1935 when Lieberman was 37 years old. At that young age he certainly never had any thoughts of becoming chief rabbi. The language “first chief rabbi of Israel” also doesn’t make any sense, as Lieberman left Israel for JTS when it was still Palestine.

Lieberman was actually a big supporter of his friend R. Isaac Herzog’s candidacy for the Chief Rabbinate. (Even when he was in Ireland, R. Herzog was a member of the advisory board of the Harry Fischel Institute which Lieberman headed at the time of R. Kook’s death.[6]) Chaim Herzog writes that his grandfather, R. Samuel Isaac Hillman, and Lieberman “organized a small campaign staff” to support R. Herzog’s election.[7] When R. Herzog was chosen, Lieberman was one of the signatories on the document proclaiming him Chief Rabbi. (I thank the late R. Eitam Henkin for sending me this.)[8]

R. Elefant then refers to R. Avraham Yisrael Moshe Solomon as a noted talmid chacham. Yet he was never a rav in Shanghai and he was not the father of Rabbi Baruch Shimon Solomon of Petah Tikvah. The story dealing with R. Kook, which is a famous one, is also mixed up. What was said to the Brisker Rav—and there are different versions concerning who said it—is that in R. Kook’s eyes all Jews are like family, and that is why he is so friendly with them. The version R. Elefant offers makes no sense, as R. Solomon’s comment to the Brisker Rav does not follow from what the Brisker Rav told him. In the note on the left side of the page, someone added [9]: “By R’ Kook every Yid is מבשרך אל תשעלם.”

The story at the bottom of the second page is unfortunate and does not make R. Elefant look good, as we see that he did not know of the view that one can cook in a keli sheni. This was obviously what Lieberman held, and this was also the view of R. Chaim Soloveitchik and R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik. R. Hershel Schachter writes as follows in Nefesh ha-Rav, p. 170:

במשנה ברורה (סי‘ שי“ח ס“ק ל“ט) הביא דעת כמה מן האחרונים להחמיר שלא לעשות תה, אפילו בכלי שני. ורבנו אמר בזה הלשון – שהסבא שלו היה מדקדק במצוות, והיה משתמש בשקיות תה בכלי שני, ואף הוא היה נוהג אחריו להקל בזה ג“כ

The story is also unfortunate as all R. Elefant had to do was ask Lieberman why he was using the tea bag in a keli sheni, and he would have been given the answer. Although one can criticize Lieberman’s association with the Jewish Theological Seminary, it is not every day that one is in the presence of someone with indescribable knowledge of Bavli, Yerushalmi, Tosefta, and Midrash. I would have assumed that R. Elefant would have taken advantage of the time he was with Lieberman for something more constructive than rebuking him.

4. In his recent Seforim Blog post here, Edward Reichman mentions R. Judah Messer Leon and his book Nofet Tzufim which was published in 1475. He also mentions that Nofet Tzufim was the answer to one of my earlier quizzes, where I asked what was the first Hebrew book published in the lifetime of its author. See here. In his post, Reichman discusses another fascinating book, R. Abraham Portaleone’s Shiltei ha-Giborim (Mantua, 1612 [Reichman mistakenly gives the date as 1607]). This book also has the honor of being “a first,” for it was the first Hebrew book to use European punctuation, including the question mark.[10]

5. The Chaim Walder affair has once again brought the issue of sexual abuse to the limelight. It also looks like the fallout from this event, unlike earlier scandals, will have a real impact in the haredi world, as many rabbis really are taking the issue seriously. What is needed is a scholarly study of how rabbis over the years have responded to the issue of sexual abuse. I am not referring to a work designed to condemn the rabbis for not doing enough, but to an academic study that would show how responses have changed over the years, how some rabbis took the matter seriously and other did not, and how with more understanding of the effects of sexual abuse rabbinic attitudes began to change.

One example of the sort of sources that would be used in such a study is R. Elijah Rabinowitz-Teomim (Aderet), Ma’aneh Eliyahu, no. 32. The Aderet deals with a case where a girl was raped by two young Jewish men. Her family wanted to report this to the police so that the rapists would receive a fitting punishment. However, the Aderet tells us that he convinced the family not to make a public issue of the matter, so as to prevent a hillul ha-shem, and to avoid confrontation with dangerous people.

דברתי אל לבם להשקיט הדבר, לבל יתחלל שם ישראל בעמים מהפקרות ופריצות צעירי הנערים, לאנוס ולנאוף ולחלל שבת ולרצוח, וגם יש סכנה בדבר לריב עם עזי פנים כמותם, ושמעו אלי

The first reason, avoidance of hillul ha-shem, certainly remains a significant factor today in the desire to keep matters of sexual abuse from being publicly aired.

Another relevant ruling, which shows how matters were handled in the past by a truly great figure, is found in R. Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (the third Lubavitcher Rebbe), Tzemah Tzedek, Yoreh Deah, no. 237. R. Schneersohn was asked the following question: A rabbi was playing with a נער on Purim and stuck his hands into the pants of the youth. The rabbi claimed that he did so because he (the rabbi) was unable to perform sexually. He thought that this was due to his small testicles, and he wanted to see if he was unusual in this regard. In other words, the rabbi was conducting a medical examination on the youth, and one can only wonder how many other boys were also subjected to this rabbi’s examinations. R. Schneersohn decided that the rabbi should not be removed from his position, as he provided a good explanation for his behavior.

What we see from these responsa (and others can be mentioned) is how much attitudes have changed in modern times. Our response would be very different than that of the Tzemach Tzedek, and I think we all would find the “justification” the abusive rabbi offered to be ludicrous, but that is only because we have been exposed to many things, including crimes perpetrated by trusted religious figures, that people in the Tzemach Tzedek’s day could never have imagined.[10]

6. As this post has discussed forgeries, I must call attention to a bombshell new book with wide-ranging implications by R. Moshe Hillel. It is titled חזון טברימון and makes a strong case that R. Yaakov Moshe Toledano created many forged documents. Often we think of forgers as shady characters, however R. Toledano was a respected rav who held a number of important positions, including Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv. In the election for Sephardic Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel, he lost to R. Isaac Nissim. R. Toledano was also a posek who authored the responsa volume Yam ha-Gadol.

It is beyond depressing to think that such a distinguished person could have been responsible for numerous forgeries. If Hillel’s claim is found to be accurate, a good of deal of scholarship, which relies on documents published by Toledano, has to be thrown out. This is every scholar’s nightmare, that the conclusions he or she reaches are based on fraudulent information.

Hillel also argues that the location of R. Moses Hayyim Luzzatto’s grave in Tiberias, which has become a popular pilgrimage site, is an invention of R. Toledano who created a phony “tradition”. For some initial discussion of Hillel’s book, see here where you can also download the book. Those interesting in purchasing a copy should contact Eliezer Brodt.

7. This summer my Torah in Motion trips resume. You can find information about them here.

8. For those interested in my Iggerot Malkhei Rabbanan, copies are still available at Mizrahi Book Store here.

9. Some years ago, I discovered at the University of Scranton a VHS tape of a 1985 lecture from Prof. Isadore Twersky. (I had already known of this lecture, as when I arrived in Scranton one of my colleagues mentioned to me how unusual it was that Twersky sat for his presentation.) I turned the VHS into a DVD, and a few weeks ago I had the tech people at Scranton turn it into a digital file and upload it to the University of Scranton’s YouTube channel. You can see the video here. This is the only video of a Twersky lecture to be found on the internet, and I am sorry that the sound is not so good. I don’t know whose idea it was to set up an Israeli flag next to Twersky as he spoke. If you look at the beginning of the video you can see that Twersky was actually sitting right in front of a cross, so maybe someone thought that a Jewish star was also needed. I know of only one other video where you can hear Twersky speaking, and that is found here where he introduces Chaim Grade.

Quiz

1. In section 4 I mentioned some bibliographical firsts, so for a quiz question I ask the following: Which Hebrew book was the first one to use footnotes (and the footnotes even used Arabic numerals)?

2. For those who would like a different sort of quiz question: Soon it will be Pesach, so please point to a halakhah on Pesach that the Shulhan Arukh decides in accord with the Rosh, while the Rama records the practice in accord with the Rambam and the Rif.

Answers should be sent to me at shapirom2 at scranton.edu

***********

[1] I did not refer to R. David Zvi Hillman’s letter which appears in Etz Hayyim 10 (5770), p. 379.

[2] As mentioned, Robinson’s book deserves an extensive review, but here is one bibliographical point. On pp. 134ff., Robinson discusses R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach’s correspondence with Rosenberg concerning the halakhic status of electricity. Robinson states that R. Auerbach’s Jan. 8, 1935 letter that strongly criticizes Rosenberg’s approach is unpublished. Yet the letter actually appears in R. Auerbach’s Meorei Esh ha-Shalem (Jerusalem, 5770), pp. 368ff.

[3] Mishpacha, Dec. 18, 2013.

[4] See here. Even before Dunner published the memoir, his copy was circulating and was placed online in June 2019. See here.

[5] Listen here at minute 72.

[6] See Sefer ha-Yovel for Harry Fischel (Jerusalem, 1935), Hebrew section, pp. 11, 20, English section, p. 8.

[7] Chaim Herzog, Living History (New York, 1996), p. 28 (called to my attention by Rabbi Jacob Yellin). According to Chaim Herzog, Lieberman would become his parents’ closest friend. See Elijah J. Schochet and Solomon Spiro, Saul Lieberman: The Man and His Work (New York, 2005), p. 52.

[8] In 1935 R. Herzog was a candidate for the chief rabbinate of Tel Aviv. The other candidates were R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik and R. Moshe Avigdor Amiel. It is of interest that the Hazon Ish supported R. Herzog’s candidacy. See Dov Eliach, Be-Sod Siah (Jerusalem, 2018), pp. 258-259. One might have expected R. Meir Berlin (Bar-Ilan), the great Mizrachi leader (and Lieberman’s father-in-law), to have supported R. Herzog or R. Amiel as they were both leading figures in Mizrachi, while R. Soloveitchik had no Mizrachi connections at this time. Yet because of his familial connection to R. Soloveitchik, Berlin put his support behind him. In a Nov. 10, 1935, letter from R. Herzog to Lieberman, R. Herzog writes as follows regarding the lack of support from Berlin, whom he calls מנהיגנו הנערץ והאהוב:

אין בלבי שום תרעומות עליו כי סוף סוף הרב הנ“ל הוא קרובו ובל תדין את חבירך וכו‘, ועוד כי בודאי עשה מה שעשה בלב שלם וטהור מתוך הכרתו הפנימית

You can see the letter here where a number of letters from the Lieberman archive have been uploaded. The source of these letters is not indicated, which means that they were not uploaded in accordance with the regulations of the Jewish Theological Seminary Library.

[9] תשעלם should be written תתעלם, and the passage comes from Isaiah 58:7. The verse actually has לא instead of אל. Yet a number of early rabbinic sources cite the verse with the word אל, so this was probably found in their texts. Indeed, critical editions of the book of Isaiah (Kittel, C.D. Ginsburg) report that many manuscripts have אל. Yet it is interesting that even though the verse appears with לא in every Tanakh printed today, rabbinic authors continue to cite the verse with אל. In fact, the Tolna Rebbe makes a big deal about how the first letters of מבשרך אל תתעלם spell אמת. See Tanḥumekha Yesha’ash’u Nafshi: Tolna (Jerusalem, 2004), pp. 235, 405, 506, 698.

[10] See Cecil Roth, The Jews in the Renaissance (Philadelphia, 1959), p. 315.

[11] R. Solomon ben Adret, She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rashba, vol. 1, no. 571(b), deals with a case where a woman accused her husband, who was also a rabbi, of: 1. sexually abusing their son, 2. having sexual relations with his slave, 3. being a heretic. However, in this case it is not clear that the woman was to be believed, as she made the accusations as part of her dispute with her husband. Things got so bad that she hired a non-Jew to bring her accusations before the government, knowing that if she was believed her husband would be burned. (She clearly wanted to get rid of him for good.) This case is discussed by Norman Roth, Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain (Leiden, 1994), pp. 195-196.