How Jews of Yesteryear Celebrated Graduation from Medical School: Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates in the 17th and 18th Centuries: An Unrecognized Genre

How Jews of Yesteryear Celebrated Graduation from Medical School:

Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates in the 17th and 18th Centuries:

An Unrecognized Genre

Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

Edward Reichman, Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, is the author of The Anatomy of Jewish Law: A Fresh Dissection of the Relationship Between Medicine, Medical History and Rabbinic Literature (Published by Koren Publishers/OU Press/YU Press, 2022), as well as the forthcoming, Pondering Pre-Modern(a) Pandemics in Jewish History: Essays Inspired by and Written during the Covid-19 Pandemic by an Emergency Medicine Physician (Shikey Press).

Prelude

As the season of graduation is upon us, I thought to look for a copy of the Hebrew poem I received upon my graduation from medical school. My search however was in vain, as I ultimately realized that no such sonnet was ever composed. When I graduated medical school some years ago, my parents, a”h, were overjoyed. They purchased me a copy of the Physician’s Prayer of Maimonides [1] (which still hangs on my wall) from the then-popular olive wood factory on the bustling Meah Shearim Street in Jerusalem. My extended family, friends, classmates, and mentors shared in my accomplishment, but no tangible expression of their happiness was forthcoming (nor did I expect one). At that time, the notion of someone authoring a poem in honor of my graduation, was, suffice it to say, nowhere to be found in the gyri of my cerebral cortex, with which I had become intimately familiar from my neuroanatomy lectures.

My transient memory, or more aptly, history lapse may perhaps be forgiven, as I currently spend a portion of my life in Early Modern Europe, immersed in the world of Jewish medical history. It is in this period where we will find the origins of my (only partially misguided) poetic yearnings.

Introduction

This year I discovered an account of a poem in honor of the graduation of an 18th century Jewish medical student. It appeared some fifty years ago in the pages of Koroth, a journal of Jewish medical history.[2] The poem is housed in the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in the Netherlands, part of the Library of the University of Amsterdam. The article, written by the late Professor Joshua Leibowitz, grandfather of the academic field of Jewish medical history, and founding editor of Koroth, discusses the poem’s author, Isaac Belinfante, a poet, bibliophile, and preacher at the Ets Haim Synagogue in Amsterdam, and provides a transcription and commentary of the poem.

As to the date of the poem, Leibowitz suggests around 1770.[3] About the recipient, whose name appears in the text of the poem, Leibowitz was unable to identify additional biographical information.

Leibowitz’s most astonishing observation, however, was that “what we have before us is an occasional poem dedicated to a topic not found in Hebrew literature, the graduation of a physician.” This was the first and only poem of this type Leibowitz had encountered.[4]

Here we revisit this poem and reclaim the lost identity of its recipient, solving one seemingly insignificant historical mystery. In the process, however, we discover that Leibowitz’s observation was profoundly mistaken, though by no fault of his own. This poem is in fact part of a much larger story in Jewish literary and medical history, one that can only now be adequately explored. We reveal an entire genre of literature in Jewish history that has gone largely unrecognized and underappreciated.

Section 1- Solving a 150-year-old Mystery

Isaac Belinfante was a prominent personality and prolific poet in eighteenth century Amsterdam. He penned poems for friends, preachers, fellow poets, and as far as we know, only one poem for a graduating physician, Moses Rodrigues.

Until today, the identity of Rodrigues and his medical institution has remained unknown.

The Date of the Poem

Leibowitz writes that, “The external evidence would favour a date round about the year 1770, as most of the printed poems of Isaac Belinfante appeared at this time.” In fact, we needn’t seek external sources. An examination of the original manuscript reveals the date at the very bottom of the page.[5]

The “A” is assumedly for annum, and the Hebrew year 5529 corresponds to 1768 or 1769. As we shall see, it refers to the latter. Leibowitz was off by only one year. I suspect he viewed a reproduction of the document, and the bottom of the page, which included the date, was simply left off the copy. Had he viewed the original, this notation would have surely not escaped his keen eye.

The Institution and Identity of the Graduate

The text of the poem does not explicitly mention the institution. The physical presence of the poem in the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in Amsterdam might reflect that the recipient was Dutch or that he graduated from a Dutch university. The author of the poem lived in Amsterdam and the last name of the recipient, Rodrigues, was common in 18th century Amsterdam. However, based on the description of the graduation ceremony in the text of the poem, as well as other factors, Leibowitz writes that “we are inclined to suppose that Dr. Rodrigues obtained his degree abroad, possibly in Padua, as most of the Dutch Jewish physicians in the 17th and 18th centuries bore foreign diplomas.”[6]

Below is the relevant verse:

The mention of the student’s rejoicing upon exiting the “house of the argument” is clearly a reference to the room where the graduation dissertation/disputation was held. The verse concludes with a description of the placing of a hat (biretta) on the graduate’s head and a ring on his finger. These are known features of the graduation ceremony from the University of Padua,[7] with which Leibowitz was quite familiar.[8]

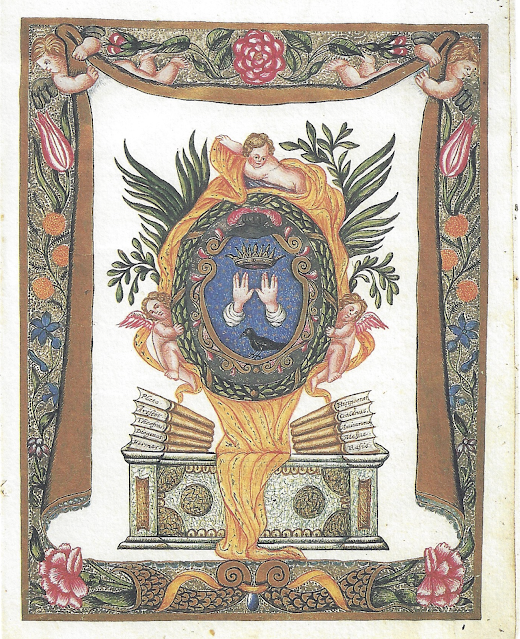

There is a spectacular illustration of this ceremony, which has gone unnoticed, found in the diploma of a Jewish medical graduate of Padua from 1687, Moses Tilche.[9]

However, these elements were not necessarily unique to Padua. Indeed, while disputations were a prominent feature of most European universities, starting from the late fifteenth century (at least), the disputationes before obtaining a doctorate had fallen into disuse in Padua.[10] Leibowitz was not aware of this. The other graduation features were also not unique to Padua and were found in the commencement ceremonies of other European universities. Leibowitz believed this poem to be a unicum, and as such, he had no basis for comparison, or reference points to identify the institution.

As for the graduate himself, Rodrigues is found nowhere in Friedenwald’s classic work,[11] nor in Nathan Koren’s expansive biographical index of Jewish physicians.[12] Moreover, despite the proliferation of online resources and databases, a Google search yields no results.

Let us consider Leibowitz’s suggestion that Rodrigues was a graduate of a foreign medical school, such as Padua. Modena and Morpurgo compiled a comprehensive list, based on extensive archival research, of the Jewish students who attended the University of Padua from 1617-1816.[13] There is no Rodrigues listed among the students who either matriculated or graduated from the University of Padua.

If Rodrigues did not attend Padua, perhaps he trained in Germany, as by this time Jews were widely accepted into German universities.[14] A review of these records again reveals no Moses Rodrigues. He is likewise not found amongst the of Jewish physicians in Poland at the time.[15]

Having ruled out a foreign institution, we return to the land of the poem’s origin. Komorowski lists the graduation and dissertation of a Moses Rodrigues from Leiden in 1788,[16] but this is some twenty years after our poem was written. Perhaps a relative.

This brings us to the work of Hindle Hes, who authored a monograph focusing exclusively on the Jewish physicians in the Netherlands.[17] Indeed, it is Professor Leibowitz who suggested to Hes the subject of her study.[18] (Perhaps he had hoped to resolve Rodrigues’ identity.) Hes lists a Mozes Rodrigues who graduated the University of Utrecht July 7, 1769,[19] the year of Belinfante’s poem. This aligns with the recipient of our poem. Rodrigues’ dissertation is pictured below.

Moses Rodrigues hailed from Madrid and trained and practiced as a surgeon in Paris prior to his stay in Amsterdam. He later completed a medical degree in the University of Utrecht.20 In the University of Utrecht student registry,[21] he is listed as Moseh Rodrigues, Hyspanus, Chirurgus Amstelodamensis (surgeon from Amsterdam), reflecting that he had already been a practicing surgeon. The other students in the registry have no such descriptor, only their names appearing.

In the four-page introduction to his Latin dissertation,[22] Rodriguez notes that he had been a practicing surgeon for twenty-seven years prior to obtaining his medical degree. Unfortunately, he provides little other personal biographical information. What would compel a practicing surgeon to obtain an additional medical degree later in life? The content of the introduction provides possible insight. At this stage of history, surgery and medicine were unique disciplines with very different training and focus. Surgeons rarely attended universities. Rodrigues strongly advocates for the synthesis and unity of surgical and medical training.

It is one thing, moreover, that I thought it best to advise publicly in this work, namely, that twin arts are by the worst design and custom and are descended from the same father from the intimacy by which they are tied together. I am pointing to the medical and surgical art, which they distinguish with differences in various places, so that the first is concerned with curing internal diseases, the second in curing external diseases. What a distinction, since I see it extended beyond what is equal, as if these parts of medicine were to be separated rather than to be joined together! I wish to subject this work to this admonition, and to prove my endeavors in promoting both arts to good and fair readers, because, when I shall have attained it, I shall seem to have rendered to me the most beautiful fruit of design or of labor.[23]

Formal university training in medicine would surely advance this objective. It is also possible that despite his years of experience, Rodrigues needed a formal degree to procure a higher-level position in the Netherlands.[24]

The content of Belinfante’s poem further corroborates our identification.[25]

In describing the medical practice of Rodrigues, Belinfante invokes distinctly surgical practices. The graduate is described as healing every “netah,” traumatic injury (from the word nituah, anatomy, or in today’s usage, surgery), as well as “one struck from a flying arrow.”[26] He seals the “mouth” of every wound and closes every opening. There are references to his treatment of afflictions of the skin and bone, as well as punctured, mauled or amputated limbs, all the domain of the barber-surgeon. This description would not have been applicable to a typical medical graduate or practitioner of medicine, but was clearly relevant to Moses Rodrigues, a practitioner of surgery. As mentioned above, Rodrigues was identified as a practicing surgeon in his matriculation record. He is also so identified on the cover page of his dissertation.

While Hes makes no mention of any poem, it is unlikely she would have come across this lone leaflet buried in the archives of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana.

In sum, we have conclusively proven that Moseh Rodrigues, graduate of Utrecht in 1769, is the recipient of Belinfante’s ode. While there is satisfaction in the historical restoration of this one obscure poem, it pales in comparison to the discovery revealed in the next section.

Section 2- An Update to Leibowitz’s Observation- Congratulatory Poems in Honor of Jewish Medical Graduates

In 1971, Leibowitz was compelled to write an article on the Rodrigues poem owing to his belief in the utter novelty of a sonnet for a Jewish medical graduate in the 18th century. How novel indeed was such an enterprise?

In the last fifty years, a number of similar poems have come to light. Experts in Jewish Renaissance poetry have written about them;[27] bibliophiles, collectors and libraries own them; Jewish medical historians have footnoted them,[28] but I suspect none of them appreciates the extent of the proverbial forest.

In the course of my research in the field of Jewish medical history, I have taken note of these poems, the majority of which were written for graduates of the University of Padua.

Italian Hebrew poetry from the Renaissance and Early Modern Period, often in broadside form, has been and remains an eminently collectible category. These poems, written for a variety of occasions including weddings and funerals, are often part of larger manuscript and book collections of bibliophiles, and while some remain in private hands, many have landed in major institutions.[29] Among these collections, we find poems written for medical graduates of Padua.[30] Thus far, I have identified a record of one hundred poems,[31] mostly in Hebrew, written for sixty five medical graduates, all from the University of Padua during the 17th to early 19th centuries.[32]

Similar poems can also be found for Jewish graduates in the Netherlands and Germany, though in smaller numbers.[33] The timeline of their appearance mirrors the transition of Jewish medical training from Padua to the Netherlands to Germany.[34]

Though Leibowitz had no access to other poems, his conjecture was Padua as the student’s place of graduation.[35] While the recipient of that particular poem happened to be a Dutch university graduate, Leibowitz’s instincts were essentially correct. We now know that this genre of poetry for the Jewish medical student, in particular in Padua, was quite common.

Below I provide some observations of the congratulatory poetry for Jewish medical graduates.

Graduates of the University of Padua[36]

Padua was the first university to allow Jews to formally train in medicine, and for a number of centuries, it was the only one. It is thus in association with the University of Padua that we find the earliest and most plentiful examples of our genre of poetry.

Chronological Span

The poems range primarily from the 1620’s to the 1780’s, with some outliers expanding the dates from 1600 to 1836. One of the earliest examples is a poem written by Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh De Modena for the graduate David Loria.[37] The original, likely in the author’s hand, resides in the Bodleian Library.[38]

Format

While the majority of the Padua poems are found in broadside format, some are found in book form, and others in manuscript. The broadside below, in honor of the graduate Jacob Coen (1691), is a typical example.[39]

Authors

The authors include mentors, fellow students or recent graduates, family members, and poets (e.g., Simha Calimani and Isaiah Romanin). Some of the prominent personalities included among the authors are Rabbi Yehuda Arye de Modena, Rabbi Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto (Ramḥal), Rabbi Solomon Marini, and Rabbi Isaac Hayyim Cantarini. The example below, written by Ramḥal in honor of the graduation of Emanuele Calvo (1724),[40] is one of at least eight poems he authored for Padua graduates.[41]

Recipients

For most of the graduates for whom we possess poems, we have only one example. A number of students however received multiple poems. For example, Joseph Hamitz (Padua, 1623) received eleven poems; Salomon Lustro (Padua, 1697)- eight; Shemarya (Marco) Morpurgo (Padua- 1747)- four. Below is a manuscript copy of a poem by Shabbetai Marini[42] in honor of Lustro. Marini, a fellow alumnus of Padua from 1685, and author of a number of graduate poems, also translated Ovid’s Metamorphosis into Hebrew.[43]

Numbers and Percentage of Students

What percentage of medical graduates received congratulatory poems? Modena and Morpurgo list a total of 325 Jewish medical graduates from 1617-1816. We have a record of poems for sixty students in this period. We thus have poems for around 20% of the medical graduates from over a 200-year period. These are only the poems of which we are aware. As these poems were typically produced as ephemeral broadsides, there are certainly poems that have not survived. The actual percentage of student poems is thus likely higher.

Location

The poems and broadsides derive primarily from the following institutions- the National Library of Israel (NLI),[44] the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), the Valmadonna Trust,[45] the British Library, the Bodleian Library, and the Kaufmann Collection at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Hungary.[46] In a number of cases, a copy of the same poem is found in more than one library. There are likely poems in both private and public hands that have not yet surfaced.

Congratulatory Poems from Netherlands and Germany

While the lion’s share of congratulatory poems are connected to Padua, there are examples from other countries as well. In the mid-seventeenth century, universities in the Netherlands (Utrecht, Franeker, Leiden) began accepting Jewish medical students. I have begun exploring the dissertations of Jewish medical graduates of the Netherlands and their value for the study of Jewish medical history. A comprehensive study remains a desideratum. The poems from the Netherlands, and from Germany as well, are not found in broadside form, but rather appended to the medical student dissertations. In Padua there were no dissertations within which to append poems, thus the poems were issued as broadsides. The broadside form was also used for other types of poetry in Italy at this time. Below is an example of a poem for a graduate of the University of Leiden, one of the premier medical schools in the world at this time. Salomon Gumpertz graduated Leiden in 1684 with the following dissertation.

Appended to the dissertation is a poem written by his relative and fellow graduate, Phillip Levi (AKA Yehoshua Feibelman).

While there is no poem at the end of Levi’s own dissertation, there is a short prayer in Hebrew composed by Levi himself to celebrate the completion of his medical studies.[47]

Blessed is the Lord who has not withheld his kindness from me and has bestowed upon me kindness and wisdom to learn the discipline of medicine. I hope that God will grant me blessing and success in my efforts and the scattered people of Israel from the four corners of the earth should be gathered, our exile should come to a speedy end, and God should send us to our land through the aegis of our Messiah speedily in our days, Amen.

The Leiden University Senate was less than enamored by Levi’s addition and despite his graduation with honors censured him for concluding with a prayer insulting Christianity. The prayer ends with a plea to God to hasten the end of the exile by bringing “our Messiah” speedily in our days. The Senate added a warning as well for any future Jewish students to abstain from similar expressions.[48]

We also find poems attached to medical dissertations of Jewish students in 18th century Germany. However, while in the Netherlands there were only three of four major universities where Jews attended, with Leiden being the most common, in Germany, there were many universities that opened their doors to Jews in the 18th century and onwards.[49] A proper study of the congratulatory poetry for Jewish medical graduates in Germany would be more challenging. Below is one example, a poem in honor of the graduation of Jonas Jeitteles[50] by Avraham HaKohen Halberstadt.

Jonas was the Chief Physician of the Jewish community of Prague. In 1784, Joseph II granted Jonas and “his successors” the right to treat patients “without consideration of their religion.” He is best remembered for his campaign supporting Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccination, for which he received the approbation of Rabbi Mordechai Banet.

Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates- A Genre Whose Time has Come

Even today, manuscripts or books hidden for centuries are occasionally discovered and brought to light.[51] In this case however, it is not one item, nor even one genizah or repository that we have revealed, rather, recently discovered and previously unidentified items in collections across the world that constitute, in their aggregate, a unique genre of poetry. Imagine that just fifty years ago the founder of the field of Jewish medical history was aware of only one example.

The collection of Jewish medical graduate poems as a whole merits recognition as a unique entity and awaits comprehensive cataloging and research.[52] To be sure, the concept of congratulatory poetry written upon completion of academic study, including medical education,[53] was not limited to Padua, nor was it limited to Jewish students. There was a broader practice of writing congratulatory poems, often in Greek or Latin, at the end of academic dissertations.[54] Nor was the use of the Hebrew language for this poetic expression restricted to the Jewish community. There was even a practice by non-Jews, typically Christian Hebraists, to write congratulatory poems in Hebrew.[55] Comparison of these different bodies of literature will surely be the substance of future dissertations, but there is no doubt that our genre will have a unique place in history.

Jews throughout history were often restricted in their choice of professions, limited to money lending or medicine. Though allowed to become physicians, Jews were barred by papal decree from obtaining a university education. It was around the 16th century that the first academic institution, the University of Padua officially accepted Jewish students. Next would be universities in the Netherlands, starting in the mid-17th century, followed by Germany in the early 18th century and others. It is in this historical context that the congratulatory poems for Jewish medical students evolved. The collective community elation at the newly allowed entrance into the world’s leading academic institutions is reflected in these sonnets.

Conclusion

Writing in 1971 about a manuscript of a poem he had recently discovered, Leibowitz claimed that the congratulatory poem for Jewish medical graduates was “a topic not found in Hebrew literature.” We now know just how untrue this statement is. It is not only “found in Hebrew literature,” but it was a common practice spanning over two hundred years and multiple countries. More examples will surely be discovered. While extensive research has been done for the Paduan poems, more work is needed to explore and identify the poems from graduates of the Netherlands, Germany,[56] and other countries.[57]

For a variety of reasons, the unique genre of poetry for the Jewish medical graduate has all but disappeared in the modern era. This at least partially reflects the dissipation of the novelty of the concept of the university-trained Jewish physician. While arguably a positive trend, it nonetheless behooves us to restore this underappreciated genre to its rightful glory. Though I hesitate to call for a resurrection of the enterprise, partially due to my personal literary ineptitude, at the very least a recollection of the practice would serve to imbue today’s Jewish medical graduates with a renewed sense of pride and historical perspective.

[1] This prayer of a “renowned Jewish physician in Egypt from the 12th century” was first published anonymously in German in 1783 in Deutches Museum 1 (January-June, 1783), 43-45. On the history of the dissemination, attribution and authorship of this prayer, see J. O. Leibowtz, Dapim Refuiim 1:13 (March, 1954), 77-81; Fred Rosner, “The Physician’s Prayer Attributed to Moses Maimonides,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 41:5 (1967), 440-457. Below is a picture (taken by the author) of a letter written by the Chief Rabbi of England, Rabbi J. H. Hertz, to Sir William Osler about the prayer.

[2] J. O. Leibowitz, “An 18th Century Manuscript Poem by I. Belinfante Honouring a Medical Graduate,” Koroth 5:7-8 (February, 1971), 427-434 (Hebrew) and LI-LIV (English).

[3] My summary of Leibowitz’s assessments is a composite of both the Hebrew and English versions of the article, which contain different information.

[4] As a footnote, he adds that he later discovered one additional poem of this type by Ephraim Luzzatto in honor of Barukh Ḥefetz (AKA Benedetto Gentili). This poem is published in Luzzatto’s collection of poetry. See Meir Letteris, ed., Ephraim Luzzatto, Eleh Bene ha-Ne’urim, (Druck und Verlag des Franz Edlen von Schmid: Wien, 1839), 43-44 (poem no. 27).

[5] Hs. Ros. Pl. B-23;L. Fuks, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of the Biblioteca Rosenthaliana University Library (Leiden, 1973), no. 317. I thank Rachel Boertjens, Curator of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, for kindly providing me a copy of the poem.

[6] For a discussion about a physician from Amsterdam who obtained a foreign diploma, see E. Reichman, “The ‘Doctored’ Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menaseh ben Israel: Forgery of ‘For Jewry’,” Seforim Blog (link), March 23, 2021. Since the publication of this article, I discovered a record of Samuel’s matriculation at the University of Leiden Medical School on July 1, 1653 (along with his cousin Josephus Abarbanel), thus further buttressing my theory that his Oxford diploma is genuine and that he had received medical training elsewhere prior to obtaining his diploma from Oxford in 1655.

[7] The ceremony also included the symbolic opening and closing of a book to reflect the transmission of knowledge, as well as the placement of a wreath, and a kiss on the graduate’s cheek.

[8] Joshua Leibowitz, “William Harvey’s Diploma from Padua, 1602,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 12 (1957), 395.

[9] Gross Family Collection, Israel. I thank William Gross for graciously providing me a copy of the diploma. On the diplomas of the Jewish graduates of the University of Padua, see E. Reichman, “Confessions of a Would-be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuvia Ha-Rofeh) and Other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,”in Kenneth Collins and Samuel Kottek, eds., Ma’ase Tuviya (Venice, 1708): Tuviya Cohen on Medicine and Science (Jerusalem: Muriel and Philip Berman Medical Library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2021), 79-127.

[10] Personal correspondence with Francesco Piovan, Chief Archivist, University of Padua (March 18, 2022). The rare disputationes that were offered were only oral, and these were for Paduan citizens who wished to be admitted into a Collegium after their doctorate.

[11] Harry Friedenwald, Jews and Medicine (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1944).

[12] Nathan Koren, Jewish Physicians: A Biographical Index (Israel Universities Press: Jerusalem, 1973).

[13] Abdelkader Modena and Edgardo Morpurgo (with editing and additions done posthumously by Aldo Luzzatto, Ladislao Munster and Vittore Colorni), Medici E Chirurghi Ebrei Dottorati E Licenziati Nell Universita Di Padova dal 1617 al 1816 (Bologna, 1967). While there have been some subsequent additions, this work, based on extensive archival research, remains the definitive reference on the Jewish medical students of Padua. It was published in Italy just four years before Leibowitz’s article was released, and he may not have yet been familiar with it.

[14] On the Jews in German medical schools, see Louis Lewin, “Die Judischen Studenten an der Universitat Frankfurtan der Oder,” Jahrbuch der Judisch Literarischen Gesellschaft 14 (1921), 217-238; Idem, “Die Judischen Studentenan der Universitat Frankfurt an der Oder,” Jahrbuch der Judisch Literarischen Gesellschaft 15 (1923), 59-96; Idem, “Die Judischen Studenten an der Universitat Frankfurt an der Oder,” Jahrbuch der Judisch Literarischen Gesellschaft 16 (1924), 43-87; Adolf Kober, “Rheinische Judendoktoren,Vornehmlich des 17 und 18 Jahrhunderts, ”Festschriftzum 75 Jährigen Bestehen des Jüdisch-Theologischen Seminars Fraenckelscher Stiftung, Volume II, (Breslau: Verlag M. & H. Marcus, 1929), 173-236; Idem, “Judische Studenten und Doktoranden der Universitat Duisberg im 18 Jahrhundert,” Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums Jahrg. 75 (N. F. 39), H. 3/4 (March/April 1931), 118-127; Monika Richarz, Der Eintritt der Juden in die akademischen Berufe: Judische Studenten Und Akademiker in Deutschland 1678-1848 (Schriftenreihe Wissenschaftlicher Abhandlungen Des Leo Baeck: Tubingen, 1974); Wolfram Kaiser and Arina Volker, Judaica Medica des 18 und des Fruhen 19 Jahrhundertsin den Bestanden des Halleschen Universitatsarchivs (Wissenschaftliche Beitrage der Martin Luther Universitat Halle-Wittenberg: Halle, 1979); M. Komorowski, Bio-bibliographisches Verzeichnisjüdischer Doktoren im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert (K. G. Saur Verlag: Munchen, 1991); Eberhard Wolff, “Between Jewish and Professional identity: Jewish Physicians in Early 19th Century Germany-The Case of Phoebus Philippson,” Jewish Studies 39 (5759), 23-34.John Efron, Medicine and the German Jews (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2001); Wolfram Kaiser,“ L’Enseignement Medical et les Juifs a L’Universite de Halle au XVIII Siecle” in Gad Freudenthal and Samuel Kottek, Melanges d’Histoire de la Medicine Hebraique (Brill: Leiden, 2003), 347-370; Petra Schaffrodt, Heidelberg-Juden ander Universitat Heidelberg: Dokumente aus Sieben Jahrhunderten (Ruprecht Karls Universitat Heidelberg Universitatsbibliothek, August, 2012); Steffi Katschke, “Jüdische Studenten an der Universität Rostock im 18. Jahrhun-dert. Ein Beitrag zur jüdischen Bildungs-und Sozialgeschichte,” in Gisela Boeck und Hans-Uwe Lammel, eds., Jüdische kulturelle und religiöse Einflüsse auf die Stadt Rostock und ihre Universität (Jewish cultural and religious influences on the city of Rostock and its university) (Rostocker Studien zur Universitätsgeschichte, Band 28: Rostock 2014), 29-40; Malgorzata Anna Maksymiak and Hans-Uwe Lammel, “Die Bützower Jüdischen Doctores Medicinae und der Orientalist O. G. Tychsen,” in Rafael Arnold, et. al., eds., Der Rostocker Gelehrte Oluf Gerhard Tychsen (1734-1815) und seine Internationalen Netzwerke (Wehrhahn Verlag, 2019), 115-133.

[15] N. M. Gelber, “History of Jewish Physicians in Poland in the 18th Century,” (Hebrew) in Y. Tirosh, ed., Shai li-Yesha‘yahu, (Tel Aviv: Ha-Merkaz le-Tarbut shel ha-Po‘el ha-Mizraḥi, 5716), 347–37.

[16] Komorowski, op.cit., 68.

[17] Hindle Hes, Jewish Physicians in the Netherlands (Van Gorcum: Assen, 1980), 140.

[18] Hes, op.cit., XI.

[19] Hes gleaned her information from an article by David Ezechial Cohen, the Dutch physician and medical historian.

“De Amsterdamasche Joodsche Chirurgijns” N.T.v.G. 74 I. (May 3, 1930), 2234-2256, esp. 2252. On Cohen, see Hes, op.cit., 26. Cohen authored a number of articles in the Netherlands Journal of Medicine on the history of Jewish surgeons and physicians in Amsterdam.

[20] Album studiosorum Academiae rheno-traiectinae MDCXXXVI-MDCCCLXXXVI. Accedunt nomina curatorum etprofessorum per eadem secula (Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht, 1886), 164.

[21] This is not noted by either Hes or Cohen.

[22] De Indicationibus pro re Nata Mutandis, University of Utrecht (July 7, 1769).

[23] Translation by Demetrios Paraschos.

[24] “Although Jews with foreign degrees were permitted to engage in medicine as general practitioners, tolerance was not extended to tertiary education.” George Weisz and William Albury, “Rembrandt’s Jewish Physician Dr. Ephraim Beuno (1599-1665): A Brief Medical History,” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 4:2 (April 2013), 1-4.

[25] The second and third stanzas from the original alongside Leibowitz’s transcription.

[26] Line 3 of stanza 2 is an allusion to Tehillim, Chap. 91.

[27] See, for example, Devora Bregman Tzror Zehuvim(Ben Gurion University: Be’er Sheva, 1997), 200 and idem,Shevil haZahav (Ben Gurion University: Be’er Sheva, 1997), 186.

[28] See Abdelkader Modena and Edgardo Morpurgo, Medici E Chirurghi Ebrei Dottorati E Licenziati Nell Universita Di Padova dal 1617 al 1816 (Bologna, 1967).

[29] The institutions include the National Library of Israel (NLI), the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS),the Valmadonna Trust, the British Libraryand the Kaufmann Collection at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Hungary. The Valmadonna Trust poems were recently integrated into the NLI, and a number of medical poems are featured in S. Liberman Mintz, S. Seidler-Feller, and D. Wachtel (eds.), The Writing on the Wall: A Catalogue of Judaica Broadsides from the Valmadonna Trust Library (London, 2015).

[30] The medical poems are sometimes found hidden and unidentified, together with other Italian occasional poems written for weddings, memorials, or other assorted events. See, for example, the previously unidentified poem written in honor of Abram Macchioro’s graduation from Padua in 1698, which is buried in a large collection of miscellaneous poems (NLI, system n. 990001920200205171, folio 19r).

[31] In book, manuscript and broadside form.

[32] Edward Reichman, “Congratulatory Poems for the Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,” forthcoming. Only a few of these poems are not extant.

[33] These are not found in broadside form.

[34] See Edward Reichman, “The Mystery of the Medical Training of the Many Isaac Wallichs: Amsterdam (1675),Leiden (1675), Padua (1683) and Halle (1703),” Hakirah 31 (Winter 2022), 313-330.

[35] Returning to the poem briefly, despite being the beneficiaries of a database of sorts, we would not be in any better position today to identify Rodrigues’ institution from internal evidence of the poem alone. While many of the Padua poems share a similar form, they come in many different varieties of size and style. While this poem has certain similar features and conforms to the general style of some of the extant poems of Padua, this alone is not dispositive. Several of the Padua poems mention the university explicitly, but inconsistently; thus, absence of its mention does not preclude the poem’s association with Padua. See, for example, the poem written by Isaiah Roman in in honor of the graduation of Yisrael Gedaliah Cases in 1733 (JTS Library Ms. 9027 V5:26). As to whether the poem’s location in the Netherlands presents a challenge for positing a Paduan origin, suffice it to say that of all extant Padua poems for Jewish medical students, a sum total of one is found in Italy (the poem for Samuele Coen 1702). The others can be found in libraries in Israel, America, England, and Hungary, though I have yet to locate as ingle Padua poem in the Netherlands. Leibowitz’s instincts however were correct, and by pure statistics alone, not knowing the identity of the student, the odds would certainly favor a Paduan source. Fortunately, this entire exercise is rendered moot once the identity of the student has been revealed.

[36] What follows is drawn from my forthcoming work on the congratulatory poems from Padua.

[37] On Loria, see Edward Reichman, “From Graduation to Contagion: Jewish Physicians Facing Plague in Padua, 1631” The Lehrhaus (link), September 8, 2020.

[38] MS. Michael 528, 60 recto, number 341.This poem was published in Simon Bernstein, Divan of Rabbi Yehuda Arye MiModena (Hebrew) (Philadelphia, 1932), n. 79.I thank Sam Sales, Superintendent, Special Collections Reading Rooms, Bodleian Library for his assistance and graciousness in locating and providing copies of this manuscript.

[39] This copy is from the JTS Library, Ms. 9027 V5:5. Another copy is found in the British Library, The Oriental and India Office Collections, Shelfmark 1978.f.3.

[40] JTS Library, Ms. 9027 V5:8. See Y. Zemora, Rabi Moshe Ḥayyim Luzzatto, Sefer HaShirim (Mosad HaRav Kook: Jerusalem, 5710), 10-11.

[41] The other graduates are Elia Consigli (1723), Elia Cesana (1727), Jacob Alpron (1727), Marco Coen (1728), Yekutiel Gordon (1732), Israel Gedalya Cases (1733), and Salomon Lampronti, (1734). On the relationship between Luzzatto and the medical students of Padua, see, for example, Morris Hoffman, trans., Isaiah Tishby, Messianic Mysticism: Moses Hayim Luzzatto and the Padua School (Oxford: The Littman Library, 2008).

[42] On Marini, see M. Benayahu,“Rabbi Avraham Ha-Kohen Mi-Zanti U-Lehakat Ha-Rof ’im Ha-Meshorerim Be-Padova,”Ha-Sifrut26 (1978): 108-40, esp. 110-111.

[43] See Jacob Goldenthal, Rieti und Marini: Dante und Ovid in Hebräischer Umkleidung (Vienna: Gerold, 1851); Laura Roumani,“Le Metamorfosidi Ovidio nella traduzione ebraica di Shabbetay Hayyim Marini di Padova” [Ovid’s Metamorphoses translated into Hebrew by Shabtai Ḥayim Marini from Padua] (PhD diss., University of Turin, 1992); idem, “The Legend of Daphne and Apollo in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Translated into Hebrew by Shabbetay Ḥayyim Marini” [in Italian], Henoch (Turin University) 13 (1991): 319–335.

[44] The NLI also has reference and reproductions of many of the poems found in the other collections.

[45] See S. Liberman Mintz, S. Seidler-Feller, and D. Wachtel (eds.), The Writing on the Wall: A Catalogue of Judaica Broadsides from the Valmadonna Trust Library (London, 2015).

[46] Prior to their landing in these major libraries and institutions, many of these poems belonged to private collectors including Moses Soave, David Kaufmann and Meir Beneyahu.

[47] See Hes, op.cit., 95.

[48] Philip Christiaan Molhuysen, Bronnen tot de geschiedenis der Leidsche Universiteit 1574-1811 (s-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff, 1916-1923), vol. 4, p. *194, entry for June 5, 1684.

[49] Examples include Heidelberg, Geissen, Berlin,Duisberg, Halle, Butzow, Rostack, Gottingen, Frankfurt, and Erlangen.

[50] See the biography of Jonas Jeitteles by his son, Yehuda ben Jona Jeitteles, Bnei haNe’urim (Prague 1821).

[51] See David Israel, “Newly Discovered Jewish Genizah in Cairo Grabbed by Egyptian Government” Jewish Press Online (March 24, 2022). Time will tell what hidden gems this cache will reveal. See also, for example, Edward Reichman, “The Discovery of a Hidden Treasure in the Vatican and the Correction of a Centuries-Old Error,” the Seforim Blog (link), January 11, 2022.

[52] The Valmadonna Trust Library, now incorporated into the National Library of Israel, began the process, and identified a separate category of broadside poems honoring Jewish medical graduates. See The Writing on the Wall, op.cit., 166-169.

[53] See Jaap Harskamp, Disertatio Medica Inauguralis… Leyden Medical Dissertations in the British Library 1593-1746 (Catalogue of a Sloane-inspired Collection) (London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1997), 270, where the author lists all the medical dissertations from the University of Leiden housed in the British Library collection that contain congratulatory poetry. There are hundreds on this list alone, and this does not include other Dutch universities.

[54] Bernhard Schirg, Bernd Roling, and Stefan Heinrich Bauhaus, eds., Apotheosis of the North: The Swedish Appropriation of Classical Antiquity around the Baltic Sea and Beyond (1650 to 1800) (De Gruyter: Berlin, 2017),64ff. As dissertations were not typically required for graduation at the University of Padua, the congratulatory poems were usually produced as separately published broadsides. However, I have as yet to find poetry written for non-Jewish medical graduates of the University of Padua.

[55] Andrea Gotz, “A Corpus of Hebrew-Language Congratulatory Poems by 17th-Century Hungarian Peregrine Students: Introducing the Hebrew Carmina Gratulatoria (HCG) Corpus and its Research Potentials,” Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica 11:3 (2019), 17-32; Jozsef Zsengeller, “Hebrew Carmina Gratulatoria from Franeker by Georg Martonfalvi and His Students,” Reformatus Szemle 114:2 (2021), 125-158.We rarely find these for medical dissertations. One example is the poem by György Magnus, found in the dissertation of Sámuel Kochmeister, “De Apoplexia,” from 1668, submitted at Wittenberg. I thank Andrea Gotz for this reference.

[56] As opposed to the case of Padua, where the poetry was published as ephemeral broadsides, and one can never know how many poems did not survive the test of time, poems found in association with dissertations are more likely to endure. Copies of student dissertations, wherein the poetry would be found, are typically preserved in university archives. We can therefore get a better idea of the true prevalence of this genre of poetry in the Netherlands and Germany. From a comprehensive review of the Jewish student dissertations, we will learn the percentage of Jewish students for whom poems were written, the language and quality of the poetry, and the identification of the authors. Moreover, these dissertations also often contain introductions, acknowledgments, and other appended material, which represent an untapped source of historical and genealogical information.

[57] Other universities opened to Jewish students in the 18thcentury, including Jagalonian University, and the universities of Pest, Lemberg, Prague, Vienna, and Warsaw, for example. Universities in Odessa and Kiev were only established in the mid to late 19thcentury. I have yet to find poems for graduates of these institutions.

.png)