The Lost Library by Dan Rabinowitz and the “Burial of Souls” by Yehuda Leib Katznelson: Different Expressions of the Same Sentiment

The Lost Library by Dan Rabinowitz and the “Burial of Souls” by Yehuda Leib Katznelson: Different Expressions of the Same Sentiment

By Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

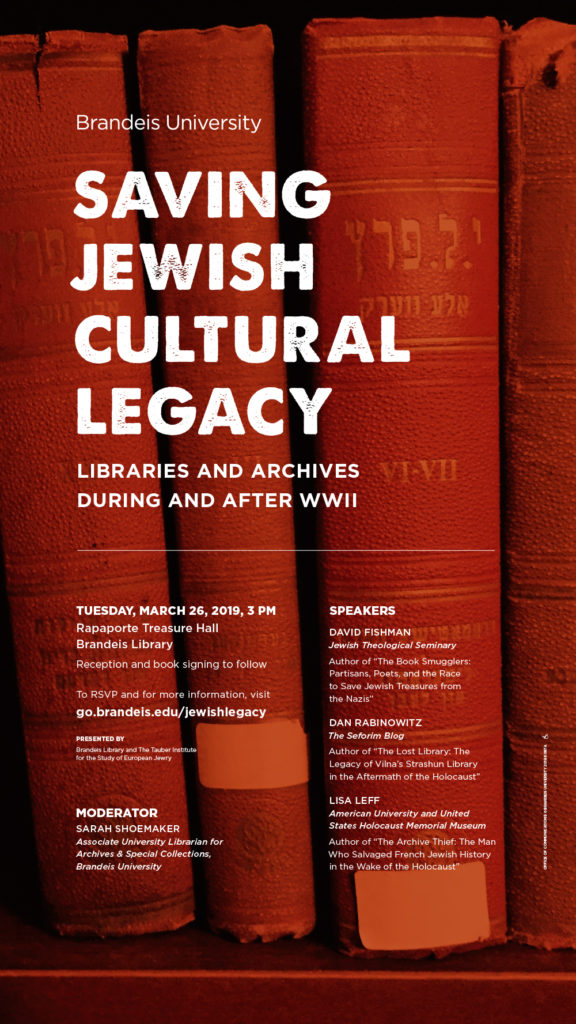

Having just completed Dan Rabinowitz’s superb book, The Lost Library, about the Strashun Library in Vilna, I am reminded of a remarkable, little-known short story written by a man who lived during the creation of the famous Strashun Library. He, like Rabinowitz, laments the loss of a famous Jewish library, though the literary nature of the lament differs. Rabinowitz has written a magnificent, captivating, thoroughly researched, historical lament. Our author has chosen the short story to metaphorically express his grief over the “loss” of one of world’s greatest Jewish libraries.

Yehuda Leib Katznelson (1846-1917),[1] a physician, poet, writer, and publicist of Hebrew Literature penned a short story in Hebrew entitled “The Burial of Souls.”[2] A summary of the story follows:

Stylistically based on Megillat Esther,[3] it tells the story of a man, Abul Said Ibn Alsalami, who possessed immense material wealth, and had everything one could wish for, save for one exception. As a child he neglected to study or read and his knowledge was sorely lacking. He realized that nothing could compensate for the lost opportunity and that he would never attain intellectual heights. His response to this fact comprises the substance of the story.

Essential to what follows is the notion that that every person is endowed with a soul while on this earth, a soul that departs and ascends to the heavens after death. However, those who amass much knowledge, and with the intent to share their knowledge and benefit others, commit their learning to paper in the form of a book, are granted an additional soul. This soul remains on earth even after the death of the author, and is embedded in the book he has written. This soul remains dormant until someone learns from this book. At that time the soul is reanimated and elevates the heavenly soul as well. In addition a new soul is replicated to dwell within the body of the book’s reader. While those with only a heavenly soul cannot advance their status after death, those with the additional soul can continue to accrue good deeds in perpetuity. For those who cannot author books, another option is available to obtain an additional soul. They can support houses of learning for those who cannot afford to study or hospitals for the poor and needy. The institutions can be called by the donor’s name and an additional soul will inhabit the walls of the building, surfacing when the children are learning or when the sick are being treated. Regretfully, Abul Said was either unaware or dismissive of the alternate track to obtaining a second soul, and had another more sinister plan.

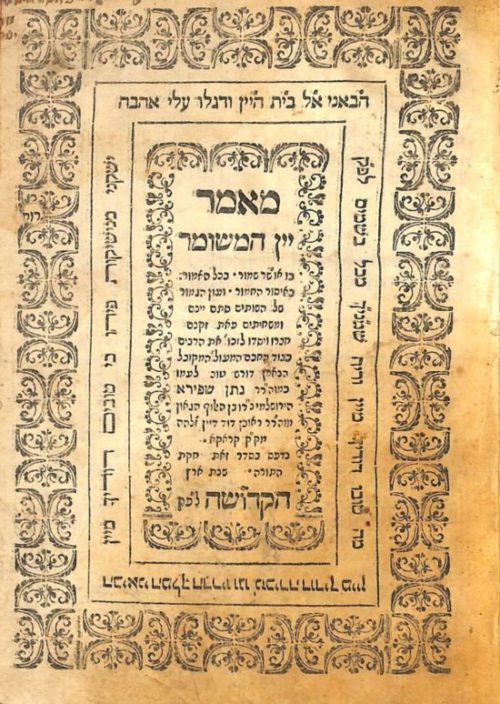

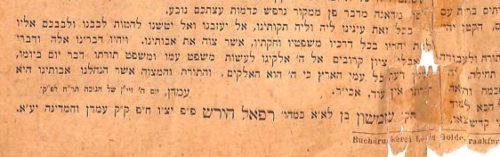

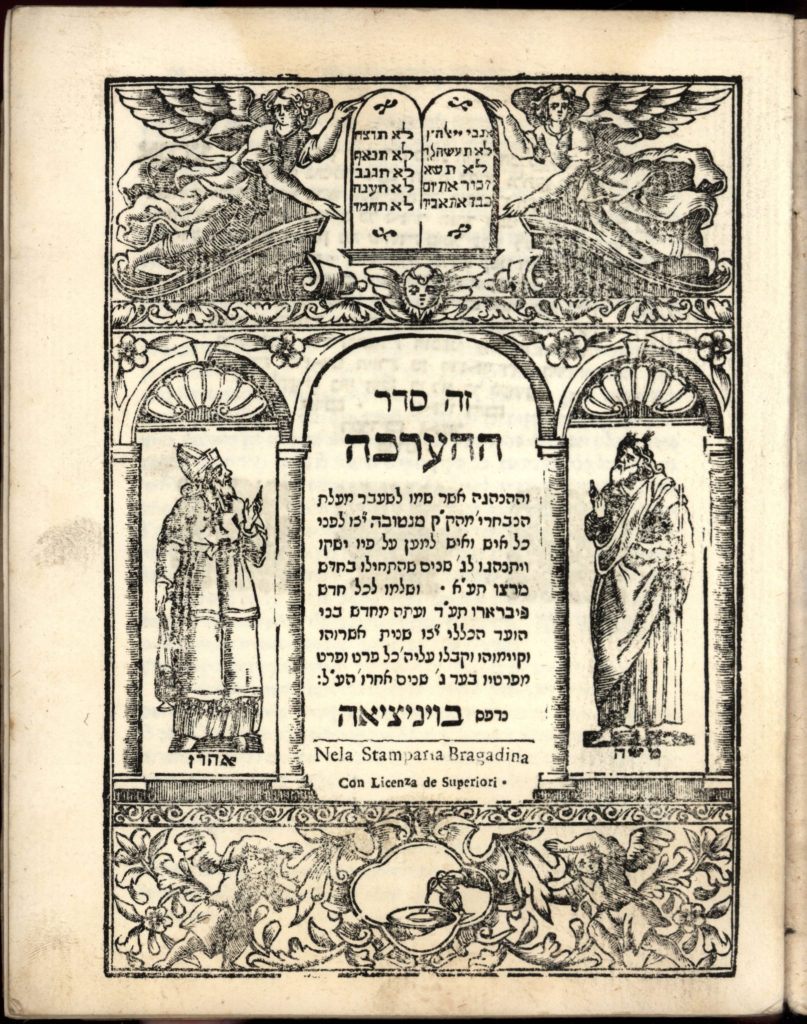

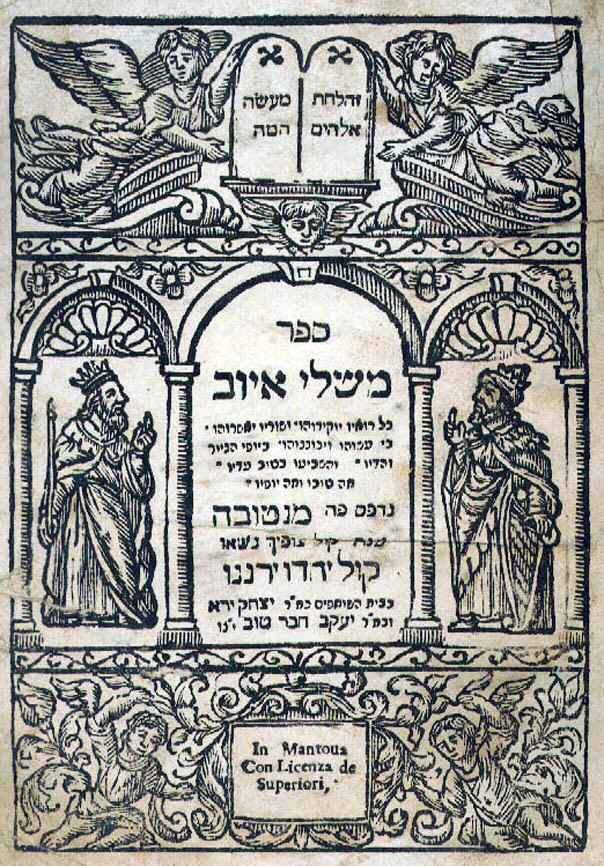

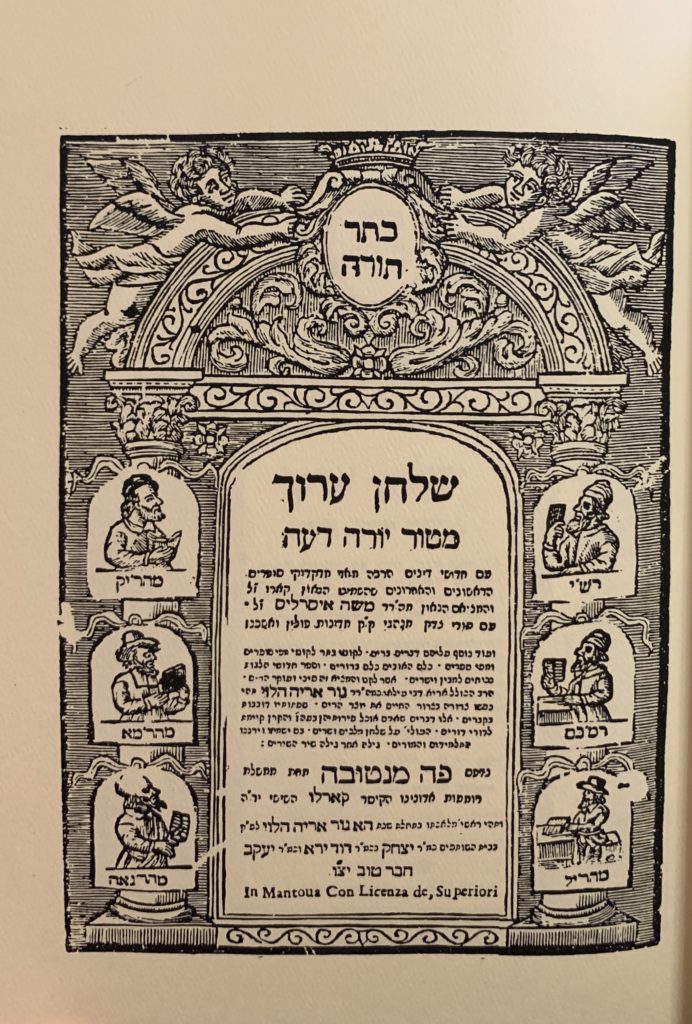

Abul Said summoned his servant, Abdul Safran,[4] who served as his literary advisor and mouthpiece, and inquired if there was a list of all Hebrew books that have ever been written. The servant responded that indeed a man by the name of Azulai had compiled just such a list. The man instructed his servant to obtain a copy of every book on the list and to spare no expense. The servant scrupulously followed Said’s command sending messengers far and wide in search of every book on the list. The inhabitants of the land were all abuzz. What could Abul Said possibly want with all these books? He is no man of letters. Surely he desires to add a soul and build a massive public library for all to learn and study freely. Alas, Abul Said had other plans.

Meanwhile books arrived at the palace from all over the world. As there was insufficient place for the treasures, all the furniture of the palace was removed, and special shelves were built from floor to ceiling to line all the available walls. Each book was bound in special hand-crafted leather and labeled with gold leaf. Upon completion of the library, it was opened to the public for three days. The totality of the literature of the nation of Israel since its inception, all under one roof.

Abu Safran had succeeded in his mission and presented this remarkable library to Abul Said, though the former could not have been prepared for his master’s next request. “If we burn the entire library will this not curtail all Jewish knowledge?” Aghast at such a suggestion, Safran quickly thought to divert his master from such a plan. He succeeded in dissuading Said from his initial request and suggested the burial of the books instead. Abul Said was amenable to the suggestion, but stipulated that the burial should not be in a Jewish cemetery, but rather in cemetery far from the Jewish community where no one would have access. The servant reluctantly carried out the wishes of his master and the site was marked with a sign that read, “Here lies buried the spirit of Israel.”

And so it was, the entire library was unceremoniously buried in a non-Jewish cemetery. On the night after the books were interred, Abul Said was unable to sleep. He was ultimately drawn into the vast hall which just the day before had housed the library. Suddenly an apparition appeared before him. Where the books had once stood were now full size paintings of their authors, cloaked in shrouds. One painting slowly began to approach Abul Said, getting larger and larger as it drew nearer and nearer. “Do you recognize me!?” shouted the man in the painting. Abul Said was silent. “I am Chaim Yosef David Azulai! It is my book that you used as a guide to gather the books that you ultimately buried.” Azulai proceeded to vilify Abul Said for burying all the additional souls of the authors, thus depriving them all of the benefits when their books are learned on earth. The story concludes with Azulai relating Abul Said’s punishment and the latter’s entreaty to repent. While Azulai considered Said’s actions irrevocable, he nonetheless offered him the opportunity to make partial amends by supporting all future publications and restoring the library to its former glory for all to use.

I read this short story some years ago and found it compelling, though only recently did I come to the realization that Katznelson[5] had not conceived of this fictional tale de novo, but rather was likely expressing his lament about a factual historical event through the vehicle of this story.

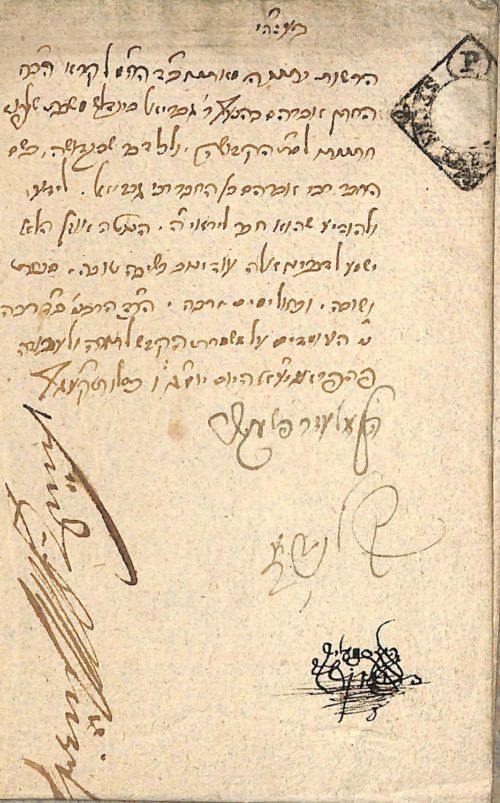

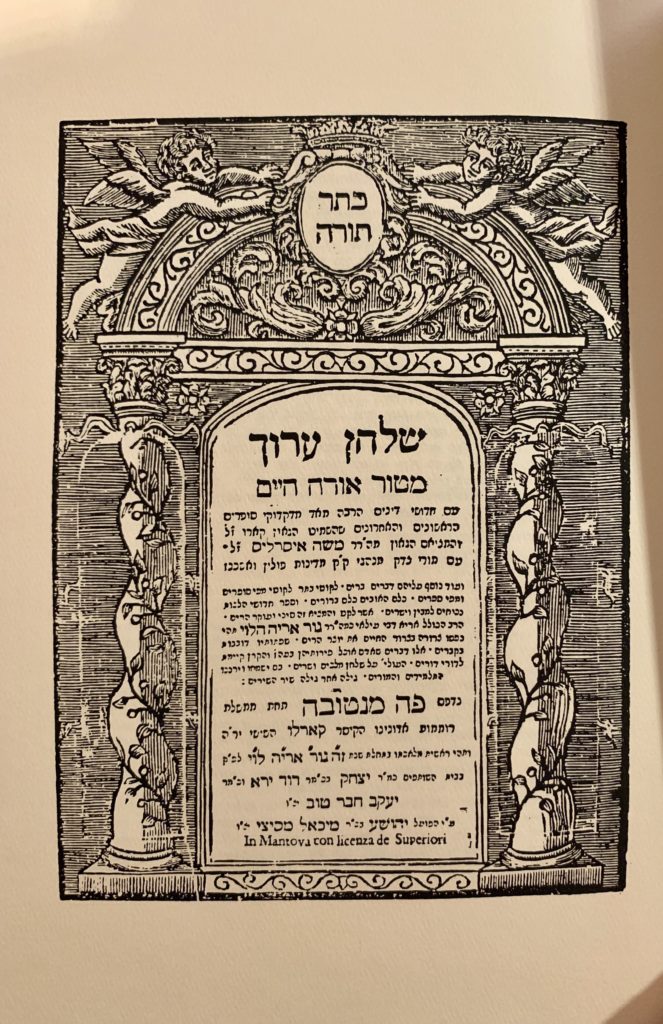

Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai (1724-1806) had indeed composed a monumental bibliographical work entitled Shem HaGedolim, which listed all extant Hebrew books until his time. In the course of his research for this project, he amassed one the world’s rarest and most comprehensive collections of Hebrew books and manuscripts up to his time. This is doubtless the work to which the servant Abu Safran refers in our story. When Azulai died, the collection was sold in its entirety by Azulai’s son to the Italian businessman Baruch Almanzi.[6] Almanzi’s son Joseph was a passionate bibliophile and poet and meticulously maintained and enhanced the collection, adding much valuable material. The great Judaica scholars of that time, including Zunz, Steinschneider and Luzzato, were welcomed into the Almanzi’s home to avail themselves of the treasures of this collection in pursuit of their research. In fact, Luzzato compiled a catalogue of the collection. When Joseph Almanzi died, however, there were apparently no heirs interested in maintaining the collection, and it was put up for auction. The name of the protagonist in our story, Alsalami, is perhaps derivative or reminiscent of Almanzi. The British Library purchased the manuscripts of the collection,[7] while the books were sold to an Amsterdam bookseller, ultimately finding their way to Temple Emmanuel in New York City, which subsequently donated the collection to Columbia University in 1893. Katznelson laments the “burial” of these precious books in a “non-Jewish cemetery,”[8] essentially precluding access to this library for the Jewish population who could benefit most from its use.[9]

I exhume this essay to both supplement and complement Rabinowitz’s lament of the loss of a great Jewish library. A number of elements of Katznelson’s story are reminiscent of the Strashun Library story – bookshelves from floor to ceiling covering every wall; open to the public with visitors from across the land; representative of the totality of rabbinic literature. Both the Azulia and Strashun collections began as the library of one scholar/bibliophile and were subsequently expanded and opened for broader access. Fortunately, however, the Strashun library books themselves remain accessible at a Jewish institution, though as Rabinowitz emphasizes, they are bereft of their unity as a distinct library and reflection of a remarkable period of intellectual Jewish history.

Perhaps the fate of the Hebrew book parallels the fate of the Jewish people, condemned to wander with only temporary respite. While the digitizing of large swaths of rabbinic literature, both print and manuscript, including parts of the Strashun Library, might partially mitigate our pain, there is no gainsaying the loss of the unity of the historically priceless Strashun collection. Let us hope that we will one day merit a permanent physical residence for the totality of Jewish/rabbinic literature,[10] but meanwhile, let us follow the instruction of Rabbi Azulai in our story and continue publishing books and supporting institutions for public access of Jewish knowledge. Rabinowitz’s remarkable contribution represents a historical continuation and expression of our longing to preserve the heritage of the books of our people, the people of the book.

[1] For a brief biography, see H. A. Savitz, “Judah Loeb Katznelson (1847-1916): Physician to the Soul of His People,” in his Profiles of Erudite Jewish Physicians and Scholars (Spertus College Press: Chicago, 1973), 56-61; On the literary contribution of Katznelson, see M. Waxman, A History of Jewish Literature 4 (Bloch Publishing: New York, 1947), 154-156. For his contribution, as well the contribution of others, to Biblical and Talmudic Medicine, see ibid., 702ff.

[2] For the full text of the story, see https://benyehuda.org/yogli/008.html. Katznelson introduces the story as a tale told to him as a child by his grandfather about events that transpired eighty years earlier. It is unclear to me whether this is factual or simply a literary device.

[3] The story is littered with literary and content allusions to the Megillah, which are literally lost in translation. My objective here is not to provide a full translation, nor to highlight these allusions, but rather to provide a summary of the story as it relates to our essay.

[4] Safran means librarian in Hebrew.

[5] Or perhaps his grandfather.

[6] The date of Rabbi Azulai’s death, and subsequent sale of his library, coincides with the time of the event mentioned in the story’s introduction, eighty years previous.

[7] See W. Wright, “The Almanzi Collection of Hebrew Manuscripts in the British Library,” The Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record 9(1866), 354-365.

[8] The “burial” analogy was invoked regarding the loss of another important Hebraica collection in an article in Der Orient in 1846 cited by Ismar Schorsch, “Catalogues and Critical Scholarship: The Fate of Jewish Collections in 19th-Century Germany,” Tablet (December 28, 2015): “It is now nearly 20 years that a similar treasure, assembled for the same purpose, was shipped out of Germany to a remote corner of the scholarly world, where buried and inaccessible it is of no value to scholarship. … Let us not commit such a travesty a second time. May the new interest in Jewish scholarship that since then has been aroused contribute to fostering an appreciation for this vital task. It is a matter of honor for Germany, and especially for its Jews, that this collection remain here.”

[9] Katznelson’s story could have equally been written about other Jewish libraries, including the exceptional library of Moses Friedland, which Rabinowitz writes was sold in 1892 to the Imperial Library of St. Petersburg, where it lay “buried” and inaccessible to the Jewish readers. See D. Rabinowitz, The Lost Library (Brandeis University Press: 2019), 52-53. The library of Rabbi David Oppenheim was likewise “buried” in 1829 when purchased by the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford.

[10] The National Jewish Library in Israel is continually bringing this dream closer to fruition. Another great Jewish library, the Valmadonna Trust Library of the late Jack Lunzer a”h, has been integrated into its collection, though a small portion of the collection was sold at auction.