Tzevi Hirsch of Nadworna’s Sefer Alpha Beta

Tzevi Hirsch of Nadworna’s Sefer Alpha Beta

by Marvin J. Heller[1]

By the riches of the sea they will be nourished, and by the treasures concealed in the sand. (Deuteronomy 33:19).

Sefer Alpha Beta (1799) Nowy Dwor

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

A primary component of the corpus of Hebrew literature is ethical works. The Torah is replete with examples of virtuous deeds, such as the patriarch Abraham’s numerous acts of kindness, and moral principles and commandments are a primary component of the taryag (613) mitzvot. Subsequent ethical works are innumerable, among the earliest and undisputedly the most popular being Pirkei Avot

Pirkei Avot, the last tractate of Mishnayot in Seder Nezikin, was redacted in the third century C. E. It has since been copied, studied regularly, and been the frequent subject of commentaries. First printed in the incunabular period, it continues to be reprinted to the present-day. The popularity of Avot is attested to by the number of editions, both independently and together with either Mishnayot or prayer books. Dr. Steven Weiss records, in his authoritative bibliography on Avot, from the first printing through 2015, 1,503 such editions.[2]

Among the many other frequently reprinted ethical works are such classics as R. Bahya ben Joseph ibn Paquda’s (second half of 11th century) Ḥovot ha-Levavot; R. Jonah ben Abraham Gerondi’s (Rabbeinu Yonah, c. 1200–1263) multiple ethical works, Iggeret ha-Teshuvah, Sha’arei Teshuvah, and Sefer ha-Yir’ah; R. Hayyim ben Bezalel’s (c.1520-1588) Sefer ha-Ḥayyim; the anonymous Orhot Zaddikim (Prague, 1581), written in Germany in the 15th century, preceded by an abbreviated Yiddish edition as Sefer ha-Middot (Isny, 1542); R. Moses Hayyim Luzzatto’s (Ramhal, 1707–1746) Mesillat Yesharim; and more recently and most notably R. Israel Meir ha-Kohen’s (Kagan, 1838-1933) Hafetz Hayyim, who is referred to today by that title.

Among the many other ethical works of value but less well known, is a small book, booklet really, by R. Tzevi Hirsch ben Shalom Zelig of Nadworna (d. 1801), entitled Sefer Alpha Beta, aphorisms based on hassidic works arranged alphabetically. Zevi Hirsch was a student (disciple) of R. Dov Baer, the Maggid of Mezhirech (d. 1772) but his primary influence was R. Jehiel Michal of Zloczow (c. 1731–1786), both among the early and foremost proponents of the Hassidic movement. Zevi Hirsch was a preacher in Dolina and afterwards was av bet din in Nadworna (Nadvornaya), in the Ivano-Frankovski section of Galicia, his name being associated with the latter community. According to R. Efraim Zalman Margulies of Brody, Zevi Hirsch “turned many sinners to repentance.” He had several illustrious talmidim (students) among them R. Menahem Mendel of Kosov, R. Tzevi Hirsch of Zydaczov, R. Abraham David of Buczacz, R. Tzevi Hirsch of Dilatin, and R. Isaac Landman of Visnitz.[3]

1818, Sefer Tsemah ha-Shem la-Tzevi, Berdichev

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Tzevi Hirsch was the author of several other titles in addition to Alpha Beta, well received and reprinted several times. Yitzhak Alfasi writes that Tzevi Hirsch was unusual for Hassidic rabbis, for, in contrast to other Hassidic leaders whose words were written by others, Tzevi Hirsch wrote his own books. That his father was a prolific author is attested to by R. David Aryeh Leib, Tzevi Hirsch’s son, in the introduction to Sefer Tsemah ha-Shem la-Tzevi (above), hassidic homilies on the weekly Torah readings (Berdichev, 1818), printed between two pages of approbations.[4]

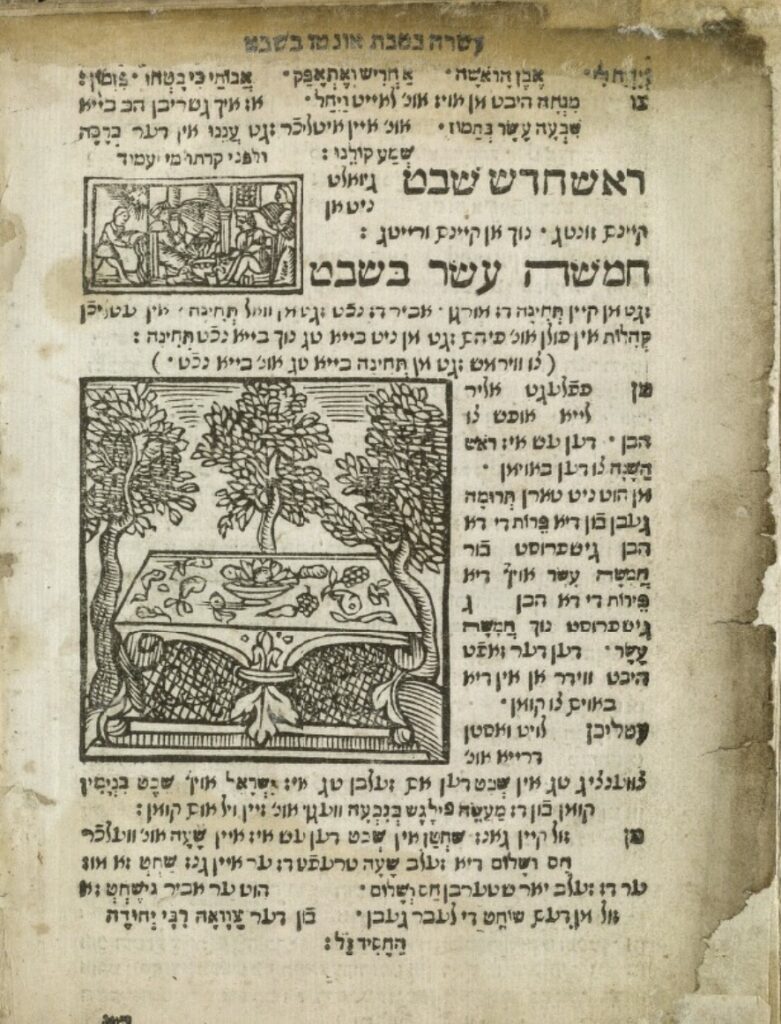

1910, Haggadah shel Pesah, Saigat

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

“This is the blessing which” (Deuteronomy 33:1) I found in his treasured files, a detailed listing of his holy writings, in his actual script, on the Torah, on the Prophets, and on many of the sayings of our sages on the Talmud and Aggadah, “founded on the holy mountains” (cf. Psalms 87:1) according to pardes (literal, allusive, discursive, and esoteric interpretations of Torah), mussar, and insight. All written by the hand of the Lord that guided him. If I brought them as they were to a press, hundreds of pages would be insufficient. . . .

Another of Tzevi Hirsch’s works is Sifte Kedoshim (Lemberg, 1873) also homilies on the weekly Torah readings and Psalms, and Haggadah shel Pesah, described on the title-page as having been concealed from the light for more than a hundred years.

We turn now to our subject book, Alpha Beta. That work, according to Ze’ev Gries, reflects the influence of the Maggid of Mezhirech.5 Initially printed as Otiyyot Mahkimot (Instructive Letters) Alpha Beta consists, as noted above, of ethical maxims arranged according to the letters of the alphabet based on Hassidic works. The date of printing is unclear, bibliographic sources giving conflicting dates and places of publication. The Bet Eked Sefarim dates the first edition to Breznitz (1796), followed soon after by Nowy Dwor (1799) and Berdichev (1817) editions. The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book records a Russia-Poland (1790) edition followed by Ostrog (1793), Zolkiew (1794), Podberezce (1796), Nowy Dwor (1799), Lemberg (1800), Russia-Poland ([1800]), and then the Berdichev (1818) edition.[6] Among the early imprints of Alpha Beta in The National Library of Israel, which has a large collection of that work, are Ostrog (1794), Nowy Dwor (1799), Poland (c. 1800), and Berdichev (1810).

Among the earliest printings of Alpha Beta is the c. 1794/1800 edition, published in octavo (80: [12] ff.) format. The title-page of that edition does not record the date or the place of printing, thus accounting for the dating variances in the bibliographic records. The Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak records it as a 1794 imprint and the press as Zolkiew. In contrast the National Library of Israel records the same edition as c. 1800, place of publication Poland. The title-pages states that it is,

1794/ 1800, Alpha Beta

Courtesy of The Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

Alpha Beta

This is the book Otiyyot Mahkimot

“A valiant man of many achievements from Kabzeel” (II Samuel 23:20, I Chronicles 11:22). In it are the order of all the middot tovot (good virtues) and the manner in which one should conduct himself as your eyes can see, “for they are life to him who finds them” (Proverbs 4:22). For the public good we have brought this booklet to press. Certainly, it will be pleasing to our brothers the children of Israel for it is “sweeter than honey” (Judges 14:18; cf. Psalms 19:11). All of your days you will taste of it and say for me it “was acquired at the full price (Genesis 23:9, I Chronicles 21:22, 24)” for it is “a ladder set earthward and its reaching heavenward] (Genesis 28:12).” Small in size but of great value.

Furthermore, we have added to this the sefer Torat ha-Adam.

Written by the rav, ha-Maggid R. Aaron ha-Levi, who is the moreh zedek (righteous teacher) in the [holy community] of Zaksanin and author of the sefer Hasdei Avot,

Tzevi Hirsch’s name does not appear on the title-page. The text follows immediately after the title-page, beginning with the phrase “‘these are the words’ (Deuteronomy 1:1) which a man shall carry out and live by them’ (Leviticus 18:5, Ezekiel 20:11, 13, 21), everlasting life, and whomever fulfills these words will assuredly be a great zaddik.” Below this opening phrase is the text, comprised of entries in alphabetic order.

Examples of the subject matter are אות א (letter alef) emet (truth); א ahavah (love): letter ב bet; bracha (blessing): ג gimmel; gemilat hesed (acts of loving kindness): ד daled, no entry; ה heh; hihor (thoughts); ו vav; ve-tikvah (and hope), ז zayin; zahiros, (caution); and concluding with ר resh ratzon (will); ש shin shtikah (silence); and ת tav: teshuvah (repentance). Entries vary in length. Examples of brief entries are:

חבר ח (friend). It is good for a person to have a friend to speak with concerning serving the Lord and to maintain distance from a bad companion, fulfilling “my sin is before me constantly” (Psalms 51:5) and seek from the Holy One, blessed be He, with a broken heart that I should not repeat these sinful deeds nor anything that is not according to the will of the Holy One, blessed be He. It is a mitzvah to very much strengthen oneself with great zeal to arise at chaztot lilah (middle of the night).7

טהרה ט (purity) A person should be pure at all times by immersing his body [in a mikvah, ritual bath) and be careful to wash his hands immediately afterwards so that there should absolutely not be any defilement on them and if possible so as to not go even daled amos. All the more when washing one’s hands in the morning one is responsible for his life (literally subject to death). Purity of his garments, as it is written “cleanse yourself and change your garments” (Genesis 35:2)and all your utensils , cups and plates shall be [ritually] clean for this arouses purity of the soul.

קדושה ק (holiness). A person should sanctify himself in all the ways that hazal (rabbinic sages) has cautioned him and as what is written, one should be very careful to sanctify all his limbs and senses.

The text of Alpha Beta is followed by Torat ha-Adam written by R. Aaron ben Judah ha-Leṿi (18th cent.), also author of Hasdei Avot.8 Torat ha-Adam is also a collection of moral maxims, concluding with a brief alphabetical list of dictums, a few a bit strange, such as כ “all your companions and your brothers will betray you: and even those who lie in your bosom will forsake you”9 and, more customary, ת “give thanks to the Lord your God and then you may go in safety on your way.”

Sefer Alpha Beta (c. 1799) Nowy Dwor

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Shortly after the first printing of Alpha Beta several other editions of Alpha Beta were published. Among them is a clearly dated תקנט (559 = 1799) Nowy Dwor edition (title-page above). Nowy Dwor, located in east-central Poland, thirty-one kilometers from Warsaw, was published at the press of Anton Krieger (Krüger), a Christian German cloth merchant.10 The title-page has a brief text, simply stating that it is Alpha Beta, Sefer Otiyyot Mahkimot and giving the place of printing. Here too Tzevi Hirsch’s name is omitted. The volume begins with a brief preface praising the work and then an introduction by Tzevi Hirsch’s son stating that it was previously printed as Otiyyot Maḥkimot, undated and without the place of publication. This edition, more complete, has added material, among it the following entry,

דיבור ד speech. Speech is very precious and should not be used in vain, and all the more to anger or for dispute, G-d forbid, derogatory speech, talebearing, disparaging speech, mockery, or falsehood . . .

Some letters are amplified, that is they are enlarged subheadings within entries, such as א ahavah (love) has been expanded to highlight אמת (truth), followed by ahavah (love), and then אכילה (eating), but this is infrequent. The text of Alpha Beta is followed by Be-Ezer ha-Zur, an alphabetical listing of concise aphorisms, for example,

ו One should be careful to not go daled amos (approximately 6 feet) without netilat yadaim (washing one’s hands).

ז One should be careful to join day and night times with Torah or tefillah (prayers).

יג One should not look at any animal, wild beast, or bird at the time they are occupied one with the other.

יד One should not look at any idol or graven image for his prayers will not be accepted for forty days, G-d forbid.

כד One should be careful not to embarrass anybody.

Sefer Alpha Beta (1799) Nowy Dwor

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

There is yet another edition late eighteenth-century edition (below) this with the location unknown but clearly dated “He guards the steps of His devout ones ורעלי חסידיו ישמר (550 = 1790)” (Samuel 2:9). If the date is correct this would be the earliest of our printings of Alpha Beta. It was noted above that the Thesaurus records a 1790 Russia-Poland edition, likely referring to this printing, presumably the first printing, prior to the Nowy Dwor edition, which may have been the second edition and the first complete printing of Alpha Beta, excepting the recorded Breznitz Alpha Beta (1796), which was not seen. However, this 1790 Alpha Beta mentions Otiyyot Mahkimot but otherwise makes no reference to earlier printings.

It stands out, however, for within the entries portions of the text are highlighted so that they now appear as several entries. For example, within the above entry on ד דיבור speech there are now two additional entries, that is, the words are highlighted in the text, for example ד דיבור speech, דין judgement, and דרך ארץ respectfulness.

1818, Alpha Beta, Russia-Poland

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Two distinct editions of Alpha Beta are recorded as 1818 imprints. One clearly dated as 1818, lacking the place of publication, is recorded as a Russia-Poland imprint and omits Zevi Hirsch’s name. The second edition, tentatively dated 1818, the place of publication also lacking, is frequently recorded as a Berdichev imprint. It clearly identifies Zevi Hirsch as the author. These are the eighth and ninth editions of Alpha Beta.

The Russia-Poland edition is dated אלך באלפא ביתא (578 = 1818) but no printer is given. It is described as 19 cm. (8 ff.). The title-page states,

Alpha Beta

Sefer

Otiyyot MahkimotThis brochure Otiyyot Mahkimot was prepared and created by “a valiant man of many achievements from Kabzeel” (II Samuel 23:20; I Chronicles 11:22). In it he arranged all the good middot (traits) and conduct with which a person should conduct himself as “your eyes can behold righteousness” (cf. Psalms 17:2) “for they are life to he who finds them” (Proverbs 4:22).

Selected from all the works of Kabbalah and by God fearing men. For the public good we have brought this brochure to press, and it will certainly be pleasing to our brothers the children of Israel for it is “sweeter than honey” (Judges 14:18) and all your life you should taste of it and say for full silver he acquired it for it is “a ladder set earthward its top reaching heavenward” (Genesis 28:13), of small size.

Tzevi Hirsch of Nadworna’s name does not appear on the title-page nor in the brief introductory paragraph that precedes the text, set in rabbinic letters.

The second 1818 edition is generally recorded as a Berdichev imprint, 16 cm. [28] ff. However, a word of caution. Isaac Yudlov notes that Avraham Yaari, in his article on Hebrew printing in Berdichev, in which Yaari records Bedichev imprints, omits this edition of Alpha Beta, suggesting that Yaari, who recorded fifty-six Berdichev titles, either did not believe it was a Berdichev imprint or omitted items that were questionable.11 Nevertheless, most bibliographies do record this edition as a Berdichev imprint.

The most active printer in Berdichev at this time was Israel Bak, who published Tzevi Hirsch’s Tsemh ha-Shem la-Tsevi, also in 1818 (above), also lacking the date of publication. Tzevi Hirsch’s name is clearly given, in enlarged bold letters, on the title-page of this edition of Alpha Beta. The title-page states,

Sefer

Alpha BetaOtiyyot Mahkimot. Illuminating as saphires, shining as lightening, standing at the top of the peak of the world, who reflects on them at all times will find in it “good reasoning” (Psalms 119:66), a healing for the soul (cf. Proverbs 16:24) and a tonic for your bones (Proverbs 3:8), arousing hearts, and bringing souls closer to their Father in heaven. That came from the mouth of the righteous, the pious, and humble, holy one of the Lord, the esteemed , the rav, the gaon, illustrious in Torah, the godly man Tzevi Hirsch the light of whose Torah shined in Nadworna and other communities.

A second paragraph states that references in the Talmud to idol worshippers and various terms used to describe them do not apply to contemporary nations who are not idol worshippers but give honor to the Torah and its followers and rule with justice and kindness. Such proforma statements are often found in contemporary Hebrew works and editions of the Talmud. The title-page is followed by the introduction of Tzevi Hirsch’s son, David Aryeh. He writes,

Behold, the above holy words that were already published by one who exited and entered in the tent of the Torah of the Rav [Tzevi Hirsch], placing it in his bag, the identity of the one who took this awesome work[12] הכר”ך הנורא הזה completely unknown (lit. obscured from sight) and there is no reason as to why in places it was abbreviated and others lengthened from the author. Now time has turned, thanks to the will of the Creator, to merit my father . . . and to bring the book to press . . .

1818, Alpha Beta, Berdichev

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel Courtesy of Steven Weiss

Ze’ev Gries and Ya’akov Shemu’el Shpiegel both note, referencing the introduction, that the reason for the omission of Tzevi Hirsch’s name in the previous printings was that, beginning with the 1790 Poland or Russia edition, Alpha Beta was frequently printed without the author’s name as the book was plagiarized or printed with changes unbeknownst to the author. The situation was corrected when Tzevi Hirsch’s son, David Aryeh, issued the Berdichev, 1818 edition.[13]

Gries, after comparing the Berdichev and the previous editions, finds that the errors are insignificant, the differences minor, the texts generally alike. He concludes that David Aryeh’s complaints are primarily based on the unauthorized use of his father’s work and the omission of the aphorisms included at the end of the Nowy Dwor edition, which may have been omitted intentionally or because the manuscript in question lacked them.[14]

Printed with this edition of Alpha Beta is Mille d’Avot, a commentary on Pirke Avot. The latter work frequently printed together with Alpha Beta. In Pirke Avot: A Thesaurus Steven Weiss records eleven editions of Alpha Beta beginning with the 1818 Berdichev edition through a 2011 Benei Brak edition.[15] In the introduction David Aryeh informs that the work of “many pearls” (Proverbs 20:15) Mille d’Avot is printed from a manuscript of his father’s, the author of that work, and also notes the publication of Tsemah ha-Shem la-Tzevi.

1848, Alpha Beta, Zolkiew

Courtesy of Otzar Hahochma

Subsequent editions of Alpha Beta clearly mention Zevi Hirsch’s name, for example the 1848 Zhitomir (Zhytomyr), edition (above). That edition was printed by Ḥanina Lipa, Aryeh Leib and Joshua Heschel Shapira, sons of Samuel Abba and Phinehas Shapira, grandsons of R. Moses Shapira. The original family press, in Slavuta, highly regarded, was forced to close after charges were brought by central authorities, but denied by the local Russian authorities, concerning the alleged murder by the Shapira family of a non-Jewish worker who had denounced the press to the authorities for printing Hebrew books without the approval of the censor. The press was reestablished by the Shapira sons in Zhitomir in 1847.

There is at least one recent edition that not only recognizes Zevi Hirsch as the author of Mille d’Avot but even emphasizes Mille d’Avot over Alpha Beta, the Lodz 1930 edition (below).

1930, Alpha Beta/ Mille d’Avot, Lodz

Courtesy of Steven Weiss

Tzevi Hirsch ben Shalom Zelig of Nadworna’s Alpha Beta has been a moderately popular work. The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book records thirteen editions, the last being a questionable Zolkiew 1850 printing; The Bet Eked Sefarim records an equal number, the latest being a Lublin 1934 printing. While Alpha Beta is highly regarded this number of printings is not, in comparison to the ethical works noted at the beginning of this work, an impressive number of editions. Alpha Beta is a small brochure, portable and more easily learned than the other books mentioned, which are large and, in some instances, multi-volume works. One would have thought that this would have resulted in many more printings of Alpha Beta rather than the relatively small number noted. Given these considerations and the value (importance) of the ethical teachings in Alpha Beta the verse quoted at the beginning would appear to be appropriate for Alpha Beta.

By the riches of the sea they will be nourished, and by the treasures concealed in the sand. (Deuteronomy 33:19).

[1] I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading this article and for his suggestions, Dr. Steven Weiss and R. Yitzhak Wilhelm, Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak Lubavitch, for their assistance.

[2] Steven J. Weiss, Pirke Avot: A Thesaurus: An Annotated bibliography of Printed Hebrew Commentaries, 1485- 2015 [Hebrew with English introduction]. A reason for the custom of saying Pirkei Avot between Pesah and Atzeret is that in these days each and every member of the people of Israel is obligated to purify himself during the days of Sefirah as the children of Israel purified themselves from the defilement of Egypt as is known from the holy Zohar. Seven weeks comparable to the seven days of niddah. (Ohev Yisrael for the Shabbat after Pesah 3:1).

[3] Yitzhak Alfasi, Entsiklopedyah la-Hasidut: Ishim כ-ת (Jerusalem, 2004), cols 603-07 [Hebrew]; Tzvi M. Rabinowicz, The Encyclopedia of Hasidism (Northvale, London, 1996), p. 335.

[4] Alfasi.

[5] Ze’ev G,ries, Sifrut ha-Hanhagot: Toldoteha u-Mekomah be-haye Haside R. Yisrael Ba’al Shem Tov (Jerusalem, 1989), p. 119 [Hebrew].

[6] Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim (Israel n.d.), alef 1422 [Hebrew]; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863. I (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 11 [Hebrew].

[7] Arising at chaztot lilah (middle of the night) refers to the kabbalistic custom of arising at the middle of the night to recite prayers and lamentations over the destruction of the Temple. (Aaron Wertheim (Author), Shmuel Himelstein (Translator), Law and Custom in Hasidism (Hoboken, 1992), p. 99.

[8] Torat ha-Adam has been printed independently several times, beginning with an Oleksinetz edition (c.1769) entitled Zot Torah ha-Adam. It is refeered to by that title in the Sudilikov (1819) and Munkatch (1904) printings.

[9] Cf. “Trust no friend, rely on no intimate; be guarded in speech with her who lies in your bosom” (Micah 7:5).

[10] Concerning the Nowy Dwor press see Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: Complete Editions, Tractates, and Other Works and the Associated Presses from the Mid-17th Century through the 18th Century (Leiden/Boston, 2019), pp. 211-18.

[11] Avraham Yaari, “Hebrew Printing at Berdichev,” Kiryat Sepher (1944), p. 100-24 [Hebrew]; Isaac Yudlov, The Israel Mehlman Collection in the Jewish National and University Library: An Annotated Catalogue of the Hebrew Books, Booklets and Pamphlets. Jerusalem 1984, pp. 190-91 no. 1171 [Hebrew].

[12] Concerning this phrase Gries references Ezekiel 1:22 the letters of הכר”ך reversed, the verse stateing “There was a likeness of an expanse above the heads of the Chayah החיה רקיע כעין הקרח, like the color of the awesome ice, spread out over their heads from above.” Also see TB Bava Mezia 24b and Hullin 95a where the phrase “obscured from sight” appears, albeit in a very different context.

[13] Gries, pp. 120-21; Ya’akov Shemu’el Shpiegel, Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Iṿri: hadar ha-meḥaber: be-Sha’ari ha-Defus (Jerusalem, 2014), pp. 25-26 [Hebrew].

[14] Gries, p. 21.

[15] In a private correspondence, dated May 27, 2020, Dr. Weiss writes that, concerning Alpha Beta, he “only listed the editions with Avot.”