How Jews of Yesteryear Celebrated Graduation from Medical School:

Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates in the 17th and 18th Centuries:

An Unrecognized Genre

Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

Edward Reichman, Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, is the author of The Anatomy of Jewish Law: A Fresh Dissection of the Relationship Between Medicine, Medical History and Rabbinic Literature (Published by Koren Publishers/OU Press/YU Press, 2022), as well as the forthcoming, Pondering Pre-Modern(a) Pandemics in Jewish History: Essays Inspired by and Written during the Covid-19 Pandemic by an Emergency Medicine Physician (Shikey Press).

Prelude

As the season of graduation is upon us, I thought to look for a copy of the Hebrew poem I received upon my graduation from medical school. My search however was in vain, as I ultimately realized that no such sonnet was ever composed. When I graduated medical school some years ago, my parents, a”h, were overjoyed. They purchased me a copy of the Physician’s Prayer of Maimonides [1] (which still hangs on my wall) from the then-popular olive wood factory on the bustling Meah Shearim Street in Jerusalem. My extended family, friends, classmates, and mentors shared in my accomplishment, but no tangible expression of their happiness was forthcoming (nor did I expect one). At that time, the notion of someone authoring a poem in honor of my graduation, was, suffice it to say, nowhere to be found in the gyri of my cerebral cortex, with which I had become intimately familiar from my neuroanatomy lectures.

My transient memory, or more aptly, history lapse may perhaps be forgiven, as I currently spend a portion of my life in Early Modern Europe, immersed in the world of Jewish medical history. It is in this period where we will find the origins of my (only partially misguided) poetic yearnings.

Introduction

This year I discovered an account of a poem in honor of the graduation of an 18th century Jewish medical student. It appeared some fifty years ago in the pages of Koroth, a journal of Jewish medical history.[2] The poem is housed in the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in the Netherlands, part of the Library of the University of Amsterdam. The article, written by the late Professor Joshua Leibowitz, grandfather of the academic field of Jewish medical history, and founding editor of Koroth, discusses the poem’s author, Isaac Belinfante, a poet, bibliophile, and preacher at the Ets Haim Synagogue in Amsterdam, and provides a transcription and commentary of the poem.

As to the date of the poem, Leibowitz suggests around 1770.[3] About the recipient, whose name appears in the text of the poem, Leibowitz was unable to identify additional biographical information.

Leibowitz’s most astonishing observation, however, was that “what we have before us is an occasional poem dedicated to a topic not found in Hebrew literature, the graduation of a physician.” This was the first and only poem of this type Leibowitz had encountered.[4]

Here we revisit this poem and reclaim the lost identity of its recipient, solving one seemingly insignificant historical mystery. In the process, however, we discover that Leibowitz’s observation was profoundly mistaken, though by no fault of his own. This poem is in fact part of a much larger story in Jewish literary and medical history, one that can only now be adequately explored. We reveal an entire genre of literature in Jewish history that has gone largely unrecognized and underappreciated.

Section 1- Solving a 150-year-old Mystery

Isaac Belinfante was a prominent personality and prolific poet in eighteenth century Amsterdam. He penned poems for friends, preachers, fellow poets, and as far as we know, only one poem for a graduating physician, Moses Rodrigues.

Until today, the identity of Rodrigues and his medical institution has remained unknown.

The Date of the Poem

Leibowitz writes that, “The external evidence would favour a date round about the year 1770, as most of the printed poems of Isaac Belinfante appeared at this time.” In fact, we needn’t seek external sources. An examination of the original manuscript reveals the date at the very bottom of the page.[5]

.png)

The “A” is assumedly for annum, and the Hebrew year 5529 corresponds to 1768 or 1769. As we shall see, it refers to the latter. Leibowitz was off by only one year. I suspect he viewed a reproduction of the document, and the bottom of the page, which included the date, was simply left off the copy. Had he viewed the original, this notation would have surely not escaped his keen eye.

The Institution and Identity of the Graduate

The text of the poem does not explicitly mention the institution. The physical presence of the poem in the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in Amsterdam might reflect that the recipient was Dutch or that he graduated from a Dutch university. The author of the poem lived in Amsterdam and the last name of the recipient, Rodrigues, was common in 18th century Amsterdam. However, based on the description of the graduation ceremony in the text of the poem, as well as other factors, Leibowitz writes that “we are inclined to suppose that Dr. Rodrigues obtained his degree abroad, possibly in Padua, as most of the Dutch Jewish physicians in the 17th and 18th centuries bore foreign diplomas.”[6]

Below is the relevant verse:

The mention of the student’s rejoicing upon exiting the “house of the argument” is clearly a reference to the room where the graduation dissertation/disputation was held. The verse concludes with a description of the placing of a hat (biretta) on the graduate’s head and a ring on his finger. These are known features of the graduation ceremony from the University of Padua,[7] with which Leibowitz was quite familiar.[8]

There is a spectacular illustration of this ceremony, which has gone unnoticed, found in the diploma of a Jewish medical graduate of Padua from 1687, Moses Tilche.[9]

However, these elements were not necessarily unique to Padua. Indeed, while disputations were a prominent feature of most European universities, starting from the late fifteenth century (at least), the disputationes before obtaining a doctorate had fallen into disuse in Padua.[10] Leibowitz was not aware of this. The other graduation features were also not unique to Padua and were found in the commencement ceremonies of other European universities. Leibowitz believed this poem to be a unicum, and as such, he had no basis for comparison, or reference points to identify the institution.

As for the graduate himself, Rodrigues is found nowhere in Friedenwald’s classic work,[11] nor in Nathan Koren’s expansive biographical index of Jewish physicians.[12] Moreover, despite the proliferation of online resources and databases, a Google search yields no results.

Let us consider Leibowitz’s suggestion that Rodrigues was a graduate of a foreign medical school, such as Padua. Modena and Morpurgo compiled a comprehensive list, based on extensive archival research, of the Jewish students who attended the University of Padua from 1617-1816.[13] There is no Rodrigues listed among the students who either matriculated or graduated from the University of Padua.

If Rodrigues did not attend Padua, perhaps he trained in Germany, as by this time Jews were widely accepted into German universities.[14] A review of these records again reveals no Moses Rodrigues. He is likewise not found amongst the of Jewish physicians in Poland at the time.[15]

Having ruled out a foreign institution, we return to the land of the poem’s origin. Komorowski lists the graduation and dissertation of a Moses Rodrigues from Leiden in 1788,[16] but this is some twenty years after our poem was written. Perhaps a relative.

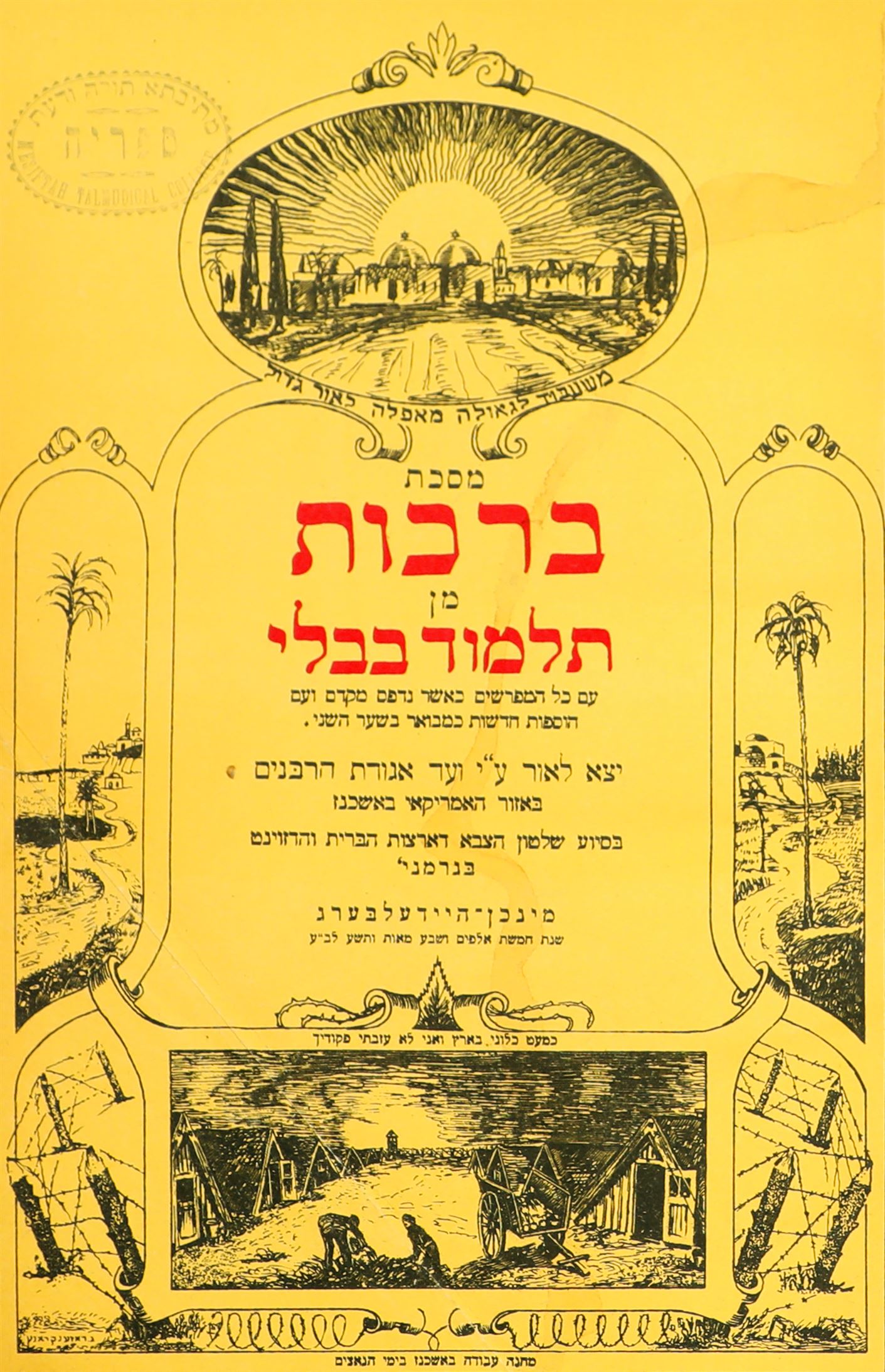

This brings us to the work of Hindle Hes, who authored a monograph focusing exclusively on the Jewish physicians in the Netherlands.[17] Indeed, it is Professor Leibowitz who suggested to Hes the subject of her study.[18] (Perhaps he had hoped to resolve Rodrigues’ identity.) Hes lists a Mozes Rodrigues who graduated the University of Utrecht July 7, 1769,[19] the year of Belinfante’s poem. This aligns with the recipient of our poem. Rodrigues’ dissertation is pictured below.

Moses Rodrigues hailed from Madrid and trained and practiced as a surgeon in Paris prior to his stay in Amsterdam. He later completed a medical degree in the University of Utrecht. In the University of Utrecht student registry,[21] he is listed as Moseh Rodrigues, Hyspanus, Chirurgus Amstelodamensis (surgeon from Amsterdam), reflecting that he had already been a practicing surgeon. The other students in the registry have no such descriptor, only their names appearing.

In the four-page introduction to his Latin dissertation,[22] Rodriguez notes that he had been a practicing surgeon for twenty-seven years prior to obtaining his medical degree. Unfortunately, he provides little other personal biographical information. What would compel a practicing surgeon to obtain an additional medical degree later in life? The content of the introduction provides possible insight. At this stage of history, surgery and medicine were unique disciplines with very different training and focus. Surgeons rarely attended universities. Rodrigues strongly advocates for the synthesis and unity of surgical and medical training.

It is one thing, moreover, that I thought it best to advise publicly in this work, namely, that twin arts are by the worst design and custom and are descended from the same father from the intimacy by which they are tied together. I am pointing to the medical and surgical art, which they distinguish with differences in various places, so that the first is concerned with curing internal diseases, the second in curing external diseases. What a distinction, since I see it extended beyond what is equal, as if these parts of medicine were to be separated rather than to be joined together! I wish to subject this work to this admonition, and to prove my endeavors in promoting both arts to good and fair readers, because, when I shall have attained it, I shall seem to have rendered to me the most beautiful fruit of design or of labor.[23]

Formal university training in medicine would surely advance this objective. It is also possible that despite his years of experience, Rodrigues needed a formal degree to procure a higher-level position in the Netherlands.[24]

The content of Belinfante’s poem further corroborates our identification.[25]

In describing the medical practice of Rodrigues, Belinfante invokes distinctly surgical practices. The graduate is described as healing every “netah,” traumatic injury (from the word nituah, anatomy, or in today’s usage, surgery), as well as “one struck from a flying arrow.”[26] He seals the “mouth” of every wound and closes every opening. There are references to his treatment of afflictions of the skin and bone, as well as punctured, mauled or amputated limbs, all the domain of the barber-surgeon. This description would not have been applicable to a typical medical graduate or practitioner of medicine, but was clearly relevant to Moses Rodrigues, a practitioner of surgery. As mentioned above, Rodrigues was identified as a practicing surgeon in his matriculation record. He is also so identified on the cover page of his dissertation.

While Hes makes no mention of any poem, it is unlikely she would have come across this lone leaflet buried in the archives of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana.

In sum, we have conclusively proven that Moseh Rodrigues, graduate of Utrecht in 1769, is the recipient of Belinfante’s ode. While there is satisfaction in the historical restoration of this one obscure poem, it pales in comparison to the discovery revealed in the next section.

Section 2- An Update to Leibowitz’s Observation- Congratulatory Poems in Honor of Jewish Medical Graduates

In 1971, Leibowitz was compelled to write an article on the Rodrigues poem owing to his belief in the utter novelty of a sonnet for a Jewish medical graduate in the 18th century. How novel indeed was such an enterprise?

In the last fifty years, a number of similar poems have come to light. Experts in Jewish Renaissance poetry have written about them;[27] bibliophiles, collectors and libraries own them; Jewish medical historians have footnoted them,[28] but I suspect none of them appreciates the extent of the proverbial forest.

In the course of my research in the field of Jewish medical history, I have taken note of these poems, the majority of which were written for graduates of the University of Padua.

Italian Hebrew poetry from the Renaissance and Early Modern Period, often in broadside form, has been and remains an eminently collectible category. These poems, written for a variety of occasions including weddings and funerals, are often part of larger manuscript and book collections of bibliophiles, and while some remain in private hands, many have landed in major institutions.[29] Among these collections, we find poems written for medical graduates of Padua.[30] Thus far, I have identified a record of one hundred poems,[31] mostly in Hebrew, written for sixty five medical graduates, all from the University of Padua during the 17th to early 19th centuries.[32]

Similar poems can also be found for Jewish graduates in the Netherlands and Germany, though in smaller numbers.[33] The timeline of their appearance mirrors the transition of Jewish medical training from Padua to the Netherlands to Germany.[34]

Though Leibowitz had no access to other poems, his conjecture was Padua as the student’s place of graduation.[35] While the recipient of that particular poem happened to be a Dutch university graduate, Leibowitz’s instincts were essentially correct. We now know that this genre of poetry for the Jewish medical student, in particular in Padua, was quite common.

Below I provide some observations of the congratulatory poetry for Jewish medical graduates.

Graduates of the University of Padua[36]

Padua was the first university to allow Jews to formally train in medicine, and for a number of centuries, it was the only one. It is thus in association with the University of Padua that we find the earliest and most plentiful examples of our genre of poetry.

Chronological Span

The poems range primarily from the 1620’s to the 1780’s, with some outliers expanding the dates from 1600 to 1836. One of the earliest examples is a poem written by Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh De Modena for the graduate David Loria.[37] The original, likely in the author’s hand, resides in the Bodleian Library.[38]

Format

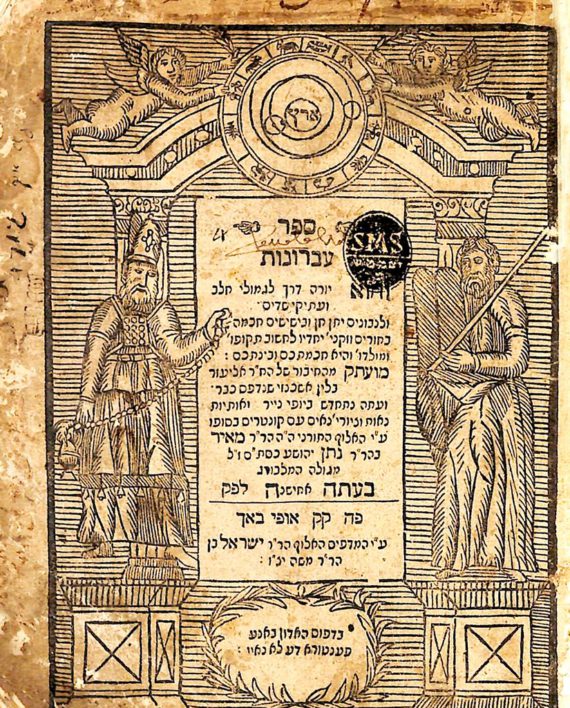

While the majority of the Padua poems are found in broadside format, some are found in book form, and others in manuscript. The broadside below, in honor of the graduate Jacob Coen (1691), is a typical example.[39]

Authors

The authors include mentors, fellow students or recent graduates, family members, and poets (e.g., Simha Calimani and Isaiah Romanin). Some of the prominent personalities included among the authors are Rabbi Yehuda Arye de Modena, Rabbi Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto (Ramḥal), Rabbi Solomon Marini, and Rabbi Isaac Hayyim Cantarini. The example below, written by Ramḥal in honor of the graduation of Emanuele Calvo (1724),[40] is one of at least eight poems he authored for Padua graduates.[41]

Recipients

For most of the graduates for whom we possess poems, we have only one example. A number of students however received multiple poems. For example, Joseph Hamitz (Padua, 1623) received eleven poems; Salomon Lustro (Padua, 1697)- eight; Shemarya (Marco) Morpurgo (Padua- 1747)- four. Below is a manuscript copy of a poem by Shabbetai Marini[42] in honor of Lustro. Marini, a fellow alumnus of Padua from 1685, and author of a number of graduate poems, also translated Ovid’s Metamorphosis into Hebrew.[43]

Numbers and Percentage of Students

What percentage of medical graduates received congratulatory poems? Modena and Morpurgo list a total of 325 Jewish medical graduates from 1617-1816. We have a record of poems for sixty students in this period. We thus have poems for around 20% of the medical graduates from over a 200-year period. These are only the poems of which we are aware. As these poems were typically produced as ephemeral broadsides, there are certainly poems that have not survived. The actual percentage of student poems is thus likely higher.

Location

The poems and broadsides derive primarily from the following institutions- the National Library of Israel (NLI),[44] the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), the Valmadonna Trust,[45] the British Library, the Bodleian Library, and the Kaufmann Collection at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Hungary.[46] In a number of cases, a copy of the same poem is found in more than one library. There are likely poems in both private and public hands that have not yet surfaced.

Congratulatory Poems from Netherlands and Germany

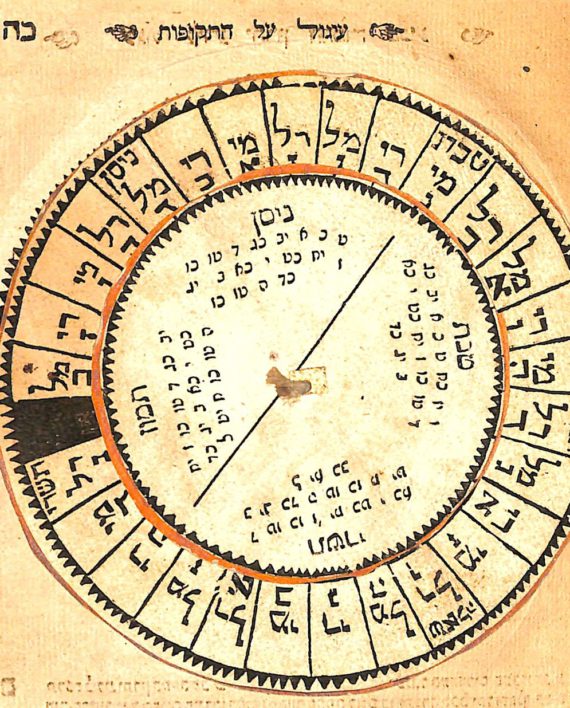

While the lion’s share of congratulatory poems are connected to Padua, there are examples from other countries as well. In the mid-seventeenth century, universities in the Netherlands (Utrecht, Franeker, Leiden) began accepting Jewish medical students. I have begun exploring the dissertations of Jewish medical graduates of the Netherlands and their value for the study of Jewish medical history. A comprehensive study remains a desideratum. The poems from the Netherlands, and from Germany as well, are not found in broadside form, but rather appended to the medical student dissertations. In Padua there were no dissertations within which to append poems, thus the poems were issued as broadsides. The broadside form was also used for other types of poetry in Italy at this time. Below is an example of a poem for a graduate of the University of Leiden, one of the premier medical schools in the world at this time. Salomon Gumpertz graduated Leiden in 1684 with the following dissertation.

Appended to the dissertation is a poem written by his relative and fellow graduate, Phillip Levi (AKA Yehoshua Feibelman).

While there is no poem at the end of Levi’s own dissertation, there is a short prayer in Hebrew composed by Levi himself to celebrate the completion of his medical studies.[47]

Blessed is the Lord who has not withheld his kindness from me and has bestowed upon me kindness and wisdom to learn the discipline of medicine. I hope that God will grant me blessing and success in my efforts and the scattered people of Israel from the four corners of the earth should be gathered, our exile should come to a speedy end, and God should send us to our land through the aegis of our Messiah speedily in our days, Amen.

The Leiden University Senate was less than enamored by Levi’s addition and despite his graduation with honors censured him for concluding with a prayer insulting Christianity. The prayer ends with a plea to God to hasten the end of the exile by bringing “our Messiah” speedily in our days. The Senate added a warning as well for any future Jewish students to abstain from similar expressions.[48]

We also find poems attached to medical dissertations of Jewish students in 18th century Germany. However, while in the Netherlands there were only three of four major universities where Jews attended, with Leiden being the most common, in Germany, there were many universities that opened their doors to Jews in the 18th century and onwards.[49] A proper study of the congratulatory poetry for Jewish medical graduates in Germany would be more challenging. Below is one example, a poem in honor of the graduation of Jonas Jeitteles[50] by Avraham HaKohen Halberstadt.

Jonas was the Chief Physician of the Jewish community of Prague. In 1784, Joseph II granted Jonas and “his successors” the right to treat patients “without consideration of their religion.” He is best remembered for his campaign supporting Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccination, for which he received the approbation of Rabbi Mordechai Banet.

Congratulatory Poems for Jewish Medical Graduates- A Genre Whose Time has Come

Even today, manuscripts or books hidden for centuries are occasionally discovered and brought to light.[51] In this case however, it is not one item, nor even one genizah or repository that we have revealed, rather, recently discovered and previously unidentified items in collections across the world that constitute, in their aggregate, a unique genre of poetry. Imagine that just fifty years ago the founder of the field of Jewish medical history was aware of only one example.

The collection of Jewish medical graduate poems as a whole merits recognition as a unique entity and awaits comprehensive cataloging and research.[52] To be sure, the concept of congratulatory poetry written upon completion of academic study, including medical education,[53] was not limited to Padua, nor was it limited to Jewish students. There was a broader practice of writing congratulatory poems, often in Greek or Latin, at the end of academic dissertations.[54] Nor was the use of the Hebrew language for this poetic expression restricted to the Jewish community. There was even a practice by non-Jews, typically Christian Hebraists, to write congratulatory poems in Hebrew.[55] Comparison of these different bodies of literature will surely be the substance of future dissertations, but there is no doubt that our genre will have a unique place in history.

Jews throughout history were often restricted in their choice of professions, limited to money lending or medicine. Though allowed to become physicians, Jews were barred by papal decree from obtaining a university education. It was around the 16th century that the first academic institution, the University of Padua officially accepted Jewish students. Next would be universities in the Netherlands, starting in the mid-17th century, followed by Germany in the early 18th century and others. It is in this historical context that the congratulatory poems for Jewish medical students evolved. The collective community elation at the newly allowed entrance into the world’s leading academic institutions is reflected in these sonnets.

Conclusion

Writing in 1971 about a manuscript of a poem he had recently discovered, Leibowitz claimed that the congratulatory poem for Jewish medical graduates was “a topic not found in Hebrew literature.” We now know just how untrue this statement is. It is not only “found in Hebrew literature,” but it was a common practice spanning over two hundred years and multiple countries. More examples will surely be discovered. While extensive research has been done for the Paduan poems, more work is needed to explore and identify the poems from graduates of the Netherlands, Germany,[56] and other countries.[57]

For a variety of reasons, the unique genre of poetry for the Jewish medical graduate has all but disappeared in the modern era. This at least partially reflects the dissipation of the novelty of the concept of the university-trained Jewish physician. While arguably a positive trend, it nonetheless behooves us to restore this underappreciated genre to its rightful glory. Though I hesitate to call for a resurrection of the enterprise, partially due to my personal literary ineptitude, at the very least a recollection of the practice would serve to imbue today’s Jewish medical graduates with a renewed sense of pride and historical perspective.

.png)

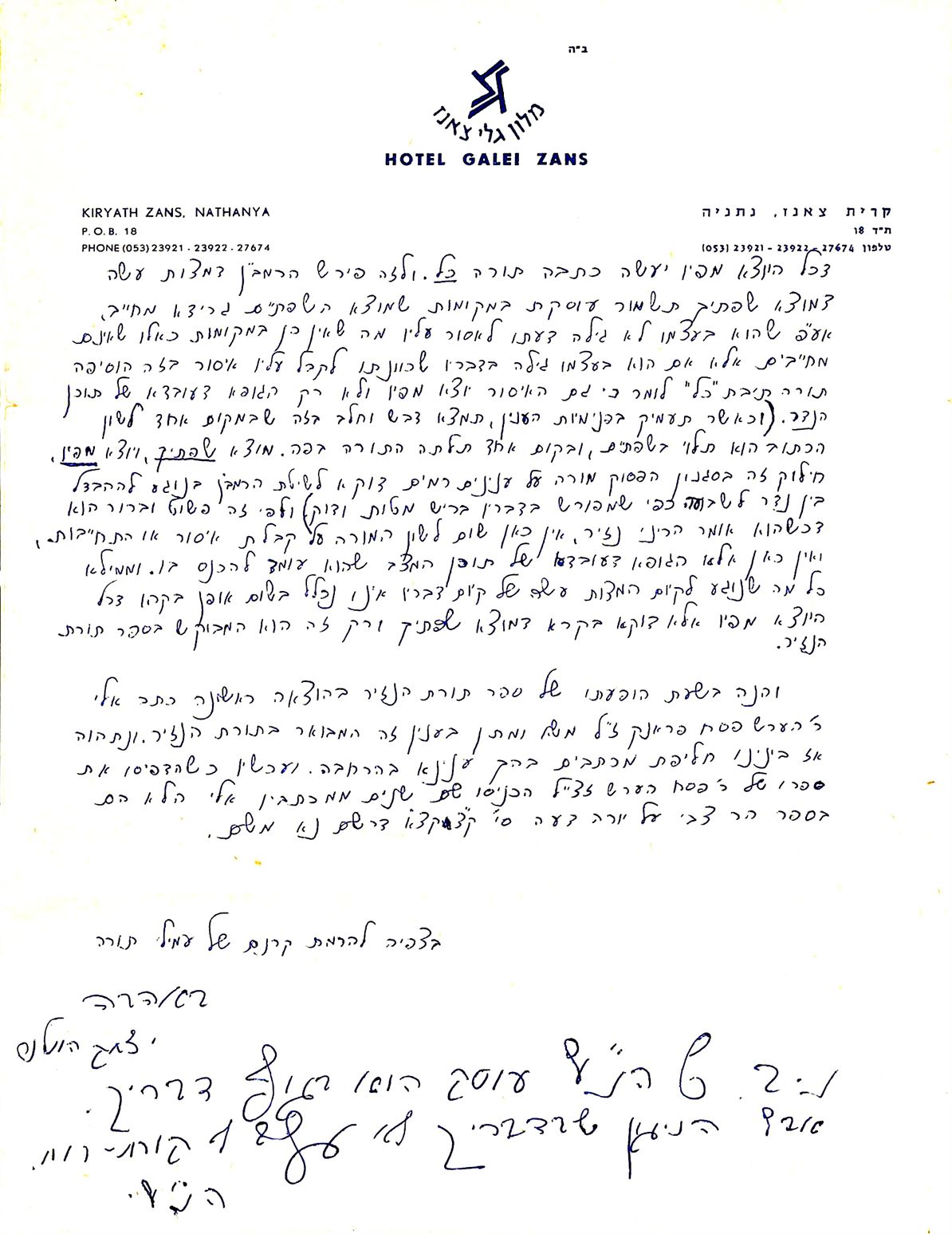

Lot 223 is a letter from R. Chaim Ozer regarding cremation. Although today after the Holocaust it seems difficult to imagine cremation widely accepted by Jews, in the early 20th century, some Orthodox rabbis permitted cremation. R. Ozer’s letter discusses one the main works, Hayyi Olam.

Lot 223 is a letter from R. Chaim Ozer regarding cremation. Although today after the Holocaust it seems difficult to imagine cremation widely accepted by Jews, in the early 20th century, some Orthodox rabbis permitted cremation. R. Ozer’s letter discusses one the main works, Hayyi Olam.