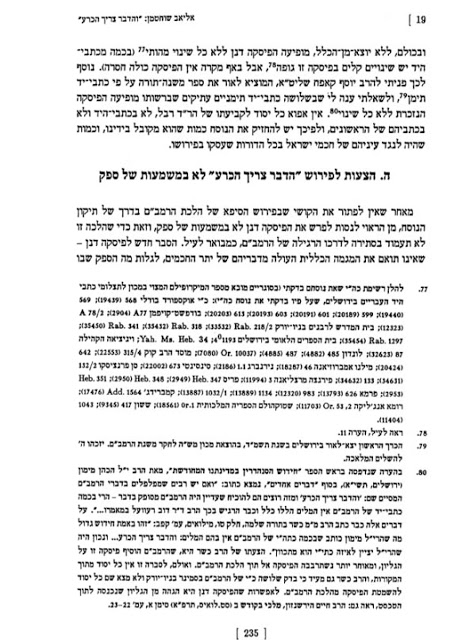

Guide and Review of Online Resources – 2022 – Part III

Guide and Review of Online Resources – 2022 – Part III

By Ezra Brand

Ezra Brand is an independent researcher based in Tel Aviv. He has an MA from Revel Graduate School at Yeshiva University in Medieval Jewish History, where he focused his research on 13th and 14th century sefirotic Kabbalah. He is interested in using digital and computational tools in historical research. He has contributed a number of times previously to the Seforim Blog (tag), and a selection of his research can be found at his Academia.edu profile. He can be reached at ezrabrand-at-gmail.com; any and all feedback is greatly appreciated. This post is a continuation. The first part of this post is here, the second here, and this is the third and final part.

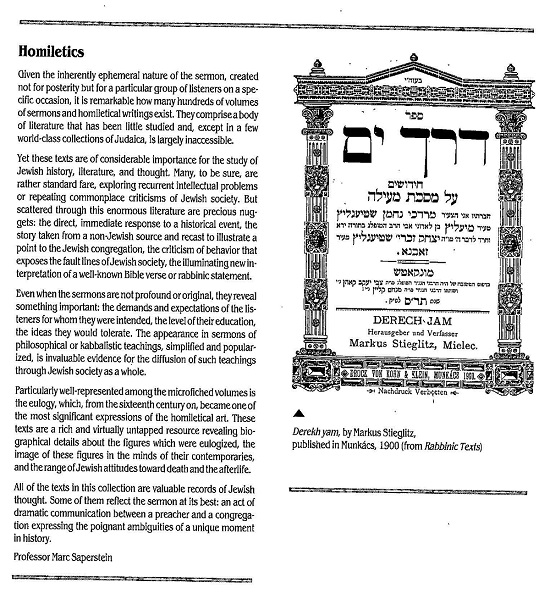

21.Articles for popular audience

Websites with open-access articles, written for a popular audience, with relatively high scholarly standards.

General

- Academy of Hebrew Language .

- See above. Besides for a selection of scholarly articles from journals, has many articles specifically written for the website.

- Recommended. Focuses on Hebrew linguistics. Great resource, at a high level of scholarship, with lots of interesting articles on all topics related to Hebrew language, throughout history.

- Wikipedia: “The Academy of the Hebrew Language was established by the Israeli government in 1953 as the “supreme institution for scholarship on the Hebrew language in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem of Givat Ram campus.” Its stated aims are to assemble and research the Hebrew language in all its layers throughout the ages; to investigate the origin and development of the Hebrew tongue; and to direct the course of development of Hebrew, in all areas, including vocabulary, grammar, writing, spelling, and transliteration.”

- TheGemara.com.

- In English.

- Focuses on Talmud Bavli. Recommended. From the About Us: “We solicit original essays that are reviewed and edited by our in-house scholars, to ensure the highest academic standards as well as maximum readability for the general audience.”

- My Jewish Learning.

- Lots of good articles. However, it mostly focuses on Bible and Modern Jewish history, which are out of the scope of this guide.

- 929- Tanach B’yachad (929 – תנך ביחד).

Newspapers and magazines

Newspapers and magazines can be a great source of scholarship, and they’re often available online. They are especially good for reviews of scholarly books, and interviews with scholars.[1] Israeli publications often have high-quality articles on Hebrew linguistics. Mostly behind paywall, with some articles not behind paywall.

Some of the best:

- Makor Rishon (מקור ראשון).

- In Modern Hebrew. Their Mussaf Shabbat (מוסף שבת) is especially good on scholarly topics.

- Wikipedia:

- “Makor Rishon is a semi-major Israeli newspaper […] Shabbat (Sabbath) – a supplement for Jewish philosophy, Judaism and literature, with an intellectual bent.”

- Haaretz (הארץ).

- In Modern Hebrew and English.[2]

- Available online: 4 April 1918 – 31 December 1997 (22,721 issues; 394,984 pages), at Israel National Library’s Jpress archive. However, not all pages in this date range are in fact available there.

- Wikipedia:

- “Haaretz is an Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel, and is now published in both Hebrew and English […]”

- Segula (סגולה).

- In Modern Hebrew and English.

- Wikipedia – Hebrew:

- “Segula is an Israeli monthly dedicated to history, published since April 2010. The magazine deals with the history of the people of Israel and general history, from the perspective that the people of Israel play an important part in world history and the historical processes leading humanity. The magazine is published monthly. An equivalent edition in English is published once every two months.”

- Tablet

- Wikipedia:

- “Tablet is an online religious magazine of news, ideas, and Jewish culture. Founded in 2009 […]”.

- Wikipedia:

- Jewish Review of Books

- Wikipedia:

- “The Jewish Review of Books is a quarterly magazine with articles on literature, culture and current affairs from a Jewish perspective. […] The magazine was launched in 2010 […]”

- Wikipedia:

Blogs

Blogs are generally not formally peer-reviewed and are generally written more informally and conversationally, but are often a great resource. With the shift from blogs to social media, many blogs have shifted to Facebook, and to a lesser extent Twitter and Reddit. (E.g., Mississippi Fred McDowel no longer posts on “On the Main Line”, but does on Facebook..) Blogs are far less active than they were. There are a lot of Facebook groups, which I’m less familiar with, and technically have to be added to and aren’t indexed by Google unfortunately (“walled gardens“, vs. “open platforms”).

- The Seforim Blog

- The Talmud Blog. Focuses on Talmud.

- Rationalist Judaism. Focuses on relationship of science and Judaism, besides for contemporary politics and hashkafa.

- Kavvanah.blog- The Book of Doctrines and Opinions

- Jewish Studies @ CUL . A blog affiliated with Columbia University, focused on Hebrew Bibliography.

- Footprints Blog – Tracing Jewish Books Through Time and Place . A blog affiliated with Columbia University, focused on Hebrew Bibliography.

- Safranim .

- Am Hasefer (עם הספר). The blog of Rambam Library of Tel Aviv, focused on Hebrew Bibliography.

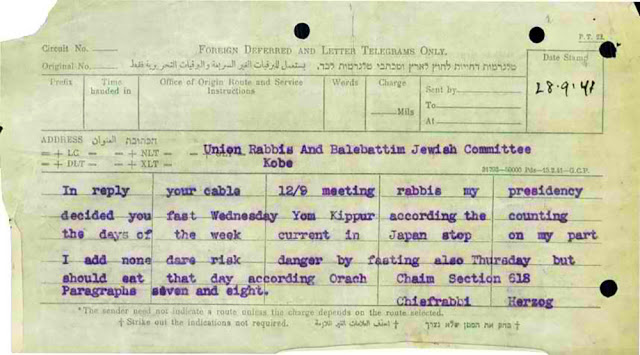

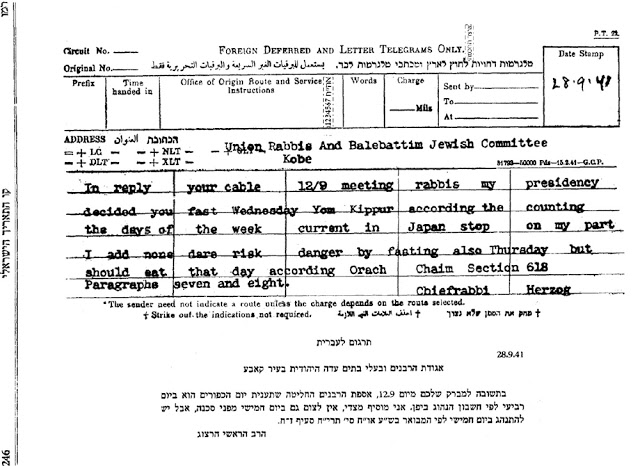

- Hagahot. Active 2005 – 2013.

- Giluy Milta B’alma (גילוי מילתא בעלמא). Masthead: “We present here new and interesting findings in Hebrew Manuscripts, and Genizah- We welcome posts in Hebrew or English.”

- On the Main Line. Blog of “Shimon Steinmetz/ Mississippi Fred MacDowell”.

- English Hebraica . Another blog of “Mississippi Fred MacDowell”. Masthead: “Chronicling Jewish and Jewish themed writing in the English language prior to the 19th century. interesting biographies, diagrams, translations, transliterations and descriptions of Jewish learning and theology from primary sources.” Active 2006 – 2007. Since then posts on Facebook and Twitter.

- What’s Bothering Artscroll? . Another blog of “Mississippi Fred MacDowell”. Active 2006 – 2008.

- Hollander Books Blog. Masthead: “A bookseller and his books, his very many books. And a few ideas.”

- Kol Safran. Masthead: “A librarian’s comments on books, copyright, management, librarianship, and libraries that don’t get the full article treatment.” Many posts on topics in Jewish bibliography, as well as visits to Jewish libraries.

- Musings of a Jewish Bookseller. Masthead: “On Jewish Books, Jewish Bookselling and Jewish Booksellers”

- Notrikon (נוטריקון). In Modern Hebrew. Masthead: ”A journey through the space of the written word, between books, periods and people … stops at different stations, who knows where we will end up.”

- Oneg Shabbat (עונג שבת). Blog of Prof. David Assaf. Many interesting posts on modern Jewish history, and on history of Hasidut.

- HaSafranim – Blog of Israel National Library (הספרנים – בלוג הספרייה הלאומית). In Modern Hebrew. Focuses on Hebrew bibliography, and topics related to Modern Israel.

- 7minim (מינים). Masthead: “This blog is intended to allow me, Tomer Persico, to comment briefly on this and that”. Has a number of posts on recent scholarly books on history of Kabbalah (though the blog mostly focuses on contemporary issues).

- HaZirah HaLeshonit – Ruvik Rozental (הזירה הלשונית – רוביק רוזנטל). Many posts on history of individual Hebew words, by a well-known and popular Hebrew linguist.

- Leshoniada (לשוניאדה). In Modern Hebrew. Focuses on Hebrew linguistics.

- Safa Ivrit (השפה העברית). In Modern Hebrew. Focuses on Hebrew linguistics. Not quite a blog, rather a wide range of short articles on sources of sayings and words.

22.Videos and Podcasts

YouTube has a lot of academic lectures. With the covid restrictions over the past two years, it has become especially common to live stream scholarly lectures (whether there’s a live component or not), and often the videos are then permanently publicly available on YouTube.[3]

Some channels:

- Academic lectures. Hundreds of lectures available. The YouTube channels seem to often be used now for live streaming of scholarly lectures:

- National Library of Israel.

- The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[4]

- Israeli university channels. For example, Hebrew University ; Bar-Ilan University.

- Scholarly organizations, such as Yad Ben-Zvi.

- Torah in Motion. A large number of lecture series. However, it mostly focuses on more modern history, contemporary theology, and on the Bible, so outside the scope of this guide. For lecture series within the scope of this guide, see for example the series with Dr. William Gewirtz, The Changing Nature of Time in Halakha, which is a four-part series that, according to the description, includes a lot of discussion of the history of the Jewish calendar.

- Seforim Chatter. Podcast hosted by Nachi Weinsten of Lakewood, NJ.[5] Has interviews with top scholars discussing their most interesting research. For example, some previous guests include: Seforim Blog’s Prof. Marc Shapiro; Jacob J. Schacter, and many more. Recommended. Also has an associated Twitter feed.

- Misfit Torah. Podcast hosted by Akiva Weisinger.

- Channeling Jewish History. Podcast hosted by my friend Joel Davidi.[6] Interviews many scholars, such as Seforim Blog contributor Prof. Marc Shapiro.

- AllDaf. A number of discussions featuring Seforim Blog’s own Rabbi Dr. Eliezer Brodt “to briefly highlight some of the Rishonim and Acharonim ‘out there’ on this masechta”, see the latest Seforim Blog post here, with links to previous.

- Tradition Podcast. Hosted by the editor of Tradition. Available on their YouTube channel. For example, one episode is an interview with Prof. Eric Lawee on a new book of his on Rashi’s Commentary.

- Am HaSefer – Rambam Library – Beit Ariela (עם הספר – ספריית הרמב”ם בית אריאלה).

- Endless videos and podcasts, each of which must be judged on its own. One genre is well-edited videos with graphics by unknown hosts. Another type is podcast-type interviews with well-known personalities. A majority of all of these are focused on Bible, which as mentioned in the introduction, are outside the scope of this guide. Also, many of them are focused more on drawing lessons, in the “self-help” genre, and less on pure scholarship.[7]

23.Twitter

Now requires registration (free) to view most content.

Essentially every organization focused on Jewish scholarship has a Twitter feed and a Facebook page. Most Twitter feeds and Facebook pages affiliated with organizations are focused on academic events, book launches, awards, etc., and so are less interesting for our purposes here. Here are the ones that especially caught my eye as having content relevant to this guide, especially bibliographical content.

- Michelle Margolis (@hchesner) / Twitter .

- “Judaica @Columbia @Footprints_Heb #dhjewish, VP @jewishlibraries, Jewish book history, Hebrew incunabula”

- Footprints Project (@Footprints_Heb) / Twitter .

- “Tracing Jewish books through time and place.”

- National Library of Israel (@NLIsrael) / Twitter .

- “Collecting & preserving the cultural treasures of #Israel & the #Jewish People. Opening access to millions of books, photos, recordings, maps, archives + more.”

- נתן הירש Nathan Hirsch (@NLITorani) / Twitter.

- “Contemporary Rabbinic literature”.

- Also on Telegram: https://t.me/s/NLITorani

- And on Facebook: Nathan Hirsch | Facebook

- DayenuPal

- #dhjewish – Twitter Search / Twitter

24.Facebook

- Norman E. Alexander Library for Jewish Studies – Home | Facebook .

- “The Norman E. Alexander Library for Jewish Studies at Columbia University collects Judaica and Hebraica in all formats and supports research.”

25.Forums

There are some great forums dedicated to academic Jewish Studies.

- Otzar HaChochma’s forum (פורום אוצר החכמה). In Modern Hebrew. Lots of really interesting discussions.

- Behadrei Haredim – Forum: Seforim and Sofrim (בחדרי חרדים – פורום: ספרים וסופרים). In Modern Hebrew.

- Judaism.stackexchange.com (Mi Yodea). In English.

26.Summary

It’s truly an exciting time to be a reader and producer of scholarship. Let me know what I’ve missed!

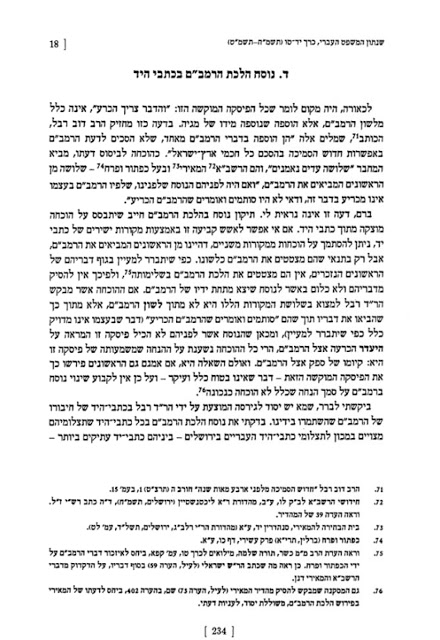

27.Appendix – Halacha Brura’s Indexes

28.Intro

Halach Brura’s index is broken down by topic, such as works of Hazal, commentaries on Mishnah, commentaries on Talmud, etc. With links to other websites (mentioned above in section “Primary Texts”) where PDFs can be found.

Halacha Brura has an intro on their index’s main page, worth quoting in full, as it makes a lot of points very relevant to this guide.

As throughout, the translation is mine, and I have translated loosely. The breakdown into numbered paragraphs and bolding is mine as well:

- “As a service to visitors to the site, the Halacha Brura Institute centralizes here links to seforim that are on the Internet at various sites, in full text, some as text and some as scans, to save the viewer the need to visit libraries.

- Naturally, the status and location of websites change from time to time, so some of the links may not work, and we apologize for that. Anyone who finds a link that does not work – please contact us, and we may be able to tell him what the correct link is.

- Warning: We have not checked the “kosherness” of the sites to which we have created links, and the user must check this himself.[8]

- Heads up: Many of the books here are from older editions; in the meantime better editions have appeared, which are not available as open-access online because of copyright law.

- We would like to thank users who know of other seforim that are online in full text to please let us know, so that we can add them to this list.

- The seforim appear in different formats, and we have dedicated symbols to each format, as follows […]

- Scans of additional books can be obtained from the Rambam Library (ספריית הרמב”ם – בית אריאלה) in Tel-Aviv – email rambaml1@gmail.com.”

29.Statistics of Halacha Brura’s index

Halacha Brura indexes seforim on the following websites, in order of number of seforim linked:[9]

- HebrewBooks

- Israel National Library

- Seforim Online

- Grimoar

- Sefaria

- Google Drive

- Torat Emet

- Wikitext

- Goethe University Frankfurt Library

- Daat

- JTS Library.

Based on my analysis, at least 45% of Halacha Brura’s links are to HebrewBooks. In fact, one can view Halacha Brura’s index as essentially a kind of index of HebrewBooks.

As for the links to open-access books in Israel National Library, I mentioned earlier that all these links are now broken. I described earlier best way to now find these open-access books on the website.

As of 15-Feb-22, Halacha Brura has 36 webpages of indexes,[10] and based on my rough estimate over 40,000 open-access seforim have been categorized.

30.Halacha Brura’s symbols

Halacha Brura’s system of symbols is not especially user-friendly. I have therefore rearranged their symbols in a more logical arrangement, see below.

I organized the order of the symbols based on the frequency of times the symbol appears in Halacha Brura’s index. I have also supplemented the symbols, based on other intros in the website:

- Major symbols:

- § HebrewBooks , PDF format.

- ჶ Israel National Library , DJVU format.

- ⋧ Israel National Library, METS format.

- ὥ Daat or Israel613, PDF format.

- ♔ text format (=transcribed). Can be Daat, Wikitext, Sefaria, or Chabad Library, among others.

- Resources especially relevant for manuscripts and early printed editions of Hazal, see Halacha Brura’s index here::

- ≡ University library :Goethe University Frankfurt Library; Russian National Library ; Jewish Theological Seminary Library ; New York Public Library.

- ★ Google Books.

- ☼ The Center for Jewish History.

- Other miscellaneous symbols, rare, only a handful of each:

- ⋇ – PDF format; Ξ – Seforim Online, PDF format; ਊ – Seforim Online, TIFF format; ↂ – Daat, PDF format.

31.Meta-index of Halacha Brura’s indexes

Page names are mostly taken from the webpage “headers”, with some changes.

The number after the page name refers to the number in the URL, that differentiates pages. So, for example, the number for תנ”ך וחז”ל is 0: http://www.halachabrura.org/library/library0.htm. , and for ראשונים על התורה it’s 3a: http://www.halachabrura.org/library/library3a.htm.

The names of the categories and sub-categories are generally taken directly from the webpages, with small changes where deemed to be helpful. The ordering of the webpages is mine.[11]

-

-

תנ”ך

-

משנה

-

תוספתא ומסכתות קטנות

-

תלמוד

-

מדרשים כסדר התנ”ך

-

מדרשים שונים

-

זוהר

-

ספרים חיצוניים

-

-

מפרשים על התורה – ראשונים – 3a

-

ראשונים על התורה

-

ביאורים על רש”י

-

-

-

נ”ך כללי

-

לפי ספר

-

הפטרות

-

-

מפרשי המשנה ; מפרשי תלמוד בבלי – ראשונים – 8

-

מפרשי המשנה

-

מפרשי תלמוד בבלי – ראשונים

-

-

מפרשי אגדות התלמוד, ירושלמי, תוספתא, מדרשים ופרקי אבות – 8l

-

מפרשי אגדות התלמוד

-

מפרשי הירושלמי

-

מפרשי תוספתא

-

מפרשי מדרשים

-

מפרשי מסכתות קטנות

-

מפרשים על פרקי אבות

-

-

מפרשי תלמוד בבלי – אחרונים – שונים – 8m

-

חידושי סוגיות

-

כללי התלמוד

-

הדרנים

-

ריאליה

-

הלכה למשה מסיני

-

-

-

גאונים

-

ספרי רש”י

-

ספרי הלכה של שאר ראשונים

-

ארבעה טורים

-

שולחן ערוך

-

מוני המצוות

-

-

הלכה – אחרונים – על שלחן ערוך – אבן העזר, חושן משפט, ונושאים שונים – 8d

-

על אבן העזר

-

על חושן משפט

-

על קדשים וטהרות

-

סת”ם

-

הלכה ורפואה

-

מנהגים ותקנות

-

כהנים ולויים

-

כללי פסיקה

-

שיעורים וזמנים

-

הולכי דרכים

-

צבא

-

ספק

-

חזקה

-

נשים

-

גוים

-

תוכחה

-

שמירת הלשון

-

-

רמב“ם ומפרשיו ; ושאלות ותשובות – 8a

-

רמב”ם ומפרשיו

-

משנה תורה

-

ספר המצוות

-

מורה נבוכים

-

פירוש המשנה

-

תשובות ואגרות

-

חיבורים אחרים

-

מפרשים על משנה תורה

-

מפרשים על מורה נבוכים

-

מפרשים על חיבורים אחרים

-

ספר המצוות

-

פירוש המשנה

-

מלות הגיון

-

-

דרכו של הרמב”ם

-

-

שאלות ותשובות

-

גאונים

-

ראשונים

-

שו”ת אחרונים ששמם כשם המחבר – לפי סדר שמו הפרטי של המחבר

-

-

-

-

הספדים

-

מועדים – אגדה

-

מועדים בהלכה ובאגדה

-

שבת

-

גאולה ומשיח

-

לימוד תורה

-

שמירת הברית והעיניים

-

טעמי המצוות

-

צוואות

-

סגולות

-

י”ג עיקרים

-

לבר מצוה

-

חינוך

-

חלומות

-

צדקה וחסד

-

נישואין

-

ברית מילה

-

שמחה

-

תפילה

-

שמירת הלשון

-

נגד לא-אורתודוקסים (רפורמים, משכילים, ציונים, מתבוללים, כופרים, משיחי שקר)

-

נגד שבתאי צבי ונגד נצרות

-

-

קבלה – 6

-

כללי

-

פירושים על הזוהר

-

ספר יצירה ופירושים עליו

-

-

-

שירה

-

סידורים ותפילות ופירושיהם

-

סידורים עם שמות

-

סידורים בלי שמות – לפי סדר שנות הדפסה

-

מחזורים לר”ה וליו”כ ושלשה רגלים

-

מחזורים בלי שמות לפי סדר שנות ההדפסה

-

תפילות מיוחדות

-

סליחות

-

ברכת החמה – לפי סדר השנים

-

פירושים על התפלה

-

סידורי מקובלים

-

-

-

כללי

-

ברסלב

-

ר’ אשר שיק

-

ר’ שלום ארוש

-

-

-

בעל התניא

-

ר’ דובער

-

הצמח צדק

-

מהר”ש

-

ר’ שלום דובער

-

ריי”צ

-

ר’ מנחם מנדל

-

חיבורים שונים

-

-

-

מונקאטש

-

ויז’ניץ

-

-

הגדות – 3c

-

עם פירושים

-

בלי פירושים

-

לקט מקורות בעניין פסח ועוד

-

-

-

ביוגרפיות

-

היסטוריה

-

ביבליוגרפיה

-

ארץ ישראל בהלכה ובאגדה

-

-

-

דקדוק ולשון

-

טעמי נגינה

-

המסורה בתנ”ך

-

אסטרונומיה וחכמת העיבור

-

לוחות שנים

-

ספרי יובל וזכרון

-

אנציקלופדיות וספרים המסודרים בסדר א””ב

-

רפואה ומדע

-

גיאוגרפיה

-

שיעורים וזמנים

-

גמטריא וראשי תיבות

-

גורלות

-

חידות

-

-

שונים – 4 (“מדור זה כולל ספרים שלא היה אפשר להכניס לאחד המדורים האחרים, מפני שנושא הספר הוא ייחודי“)

-

שפות זרות (לא–עברית) ; לא–אורתודוקס ; סיפורים ; כתבי יד ; הומור – 4w

-

שפות זרות

-

אידיש

-

אנגלית

-

גרמנית

-

ספרדית

-

צרפתית

-

לאדינו

-

ערבית-יהודית

-

פרסית

-

רוסית

-

לטינית

-

הונגרית

-

-

לא-אורתודוקס

-

משכילים

-

רפורמים

-

שבתאים

-

קראים

-

שומרונים

-

-

סיפורים

-

כתבי יד

-

הומור

-

[1] For an interesting example of newspaper interviews and lectures on YouTube being used as evidence in scholarly discussion, see Prof. Bezalel Bar-Kochva’s critique of Prof. Rachel Elior: https://www.tau.ac.il/sites/tau.ac.il.en/files/media_server/imported/508/files/2014/10/elior-25.11.2013.pdf. However, it must be admitted that that’s an unusual case.

[2] Example of article on Hebrew linguistics, on the word “שחצן”: המילה שַׁחְצָן: מה הקשר בין אריות לנחשים וביניהם לבין יוהרה?: https://www.haaretz.co.il/magazine/the-edge/mehasafa/.premium-1.2853618

[3] As for podcasts, many podcasts are also available on YouTube. For example, see below for the podcast “Channeling Jewish History”.

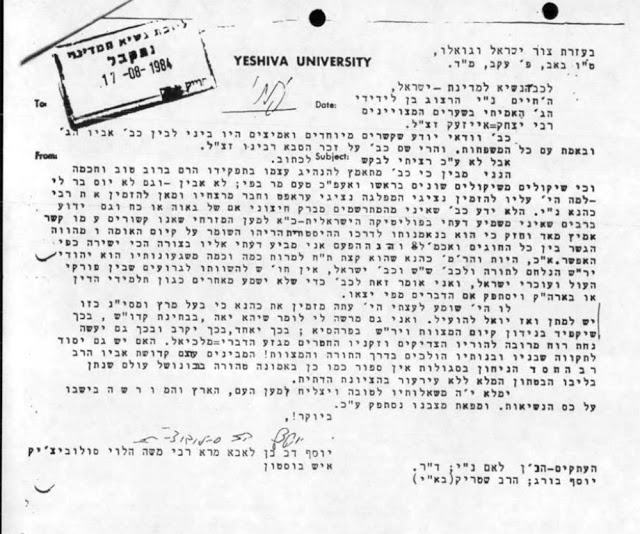

[4] See here: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities – YouTube > “Past live streams”. Recent example that showed in my email inbox of youtube being used for live streaming of a scholarly lecture:

When I was sent this link, Gmail even knew to attach the YouTube preview in the email.

[5] Introduction Show, Seforimchatter, https://seforimchatter.buzzsprout.com/1218638/4587641-introduction-show, July 15, 2020, Season 1 Episode 18. (Accessed 13-Feb-22).

[6] Admin of the Facebook group “Channeling Jewish History Group”.

[7] A few examples: R’ Dr. Ari Lamm’s podcast called “Good Faith Effort”; Michael Eisenberg’s YouTube channel.

[8] The Halacha Brura indexes indeed link to a nice amount of non-Orthodox works. A dedicated sub-category for non-Orthodox writings appears at the webpage indexing eclectic works (“ספרי קודש שונים”), together with “Foreign-language”, “Stories”, “Manuscripts”, and “Humor”. It should be pointed out that many of these non-Orthodox books have been removed from HebrewBooks, and are no longer available there.

[9] My analysis. I “scraped” a few webpages of Halacha Brura via relatively simple copy-paste and text manipulation in Google Sheets, to use as a sample.

[10] The number of webpages is always going up. When I started my research, there were 33 pages. They then split the page on “Journals” into 4 pages, due to indexing hundreds of additional links.

[11] As I’ve mentioned before, this index by Halacha Brura is a work-in-progress. They are still actively spinning off new pages. Therefore, this meta-index is likely to have some out-of-date info as time goes on.