An Illustrated Life of an Illustrious Renaissance Jew Rabbi Doctor Shimshon Morpurgo (1681-1740)

An Illustrated Life of an Illustrious Renaissance Jew Rabbi Doctor Shimshon Morpurgo (1681-1740)

By Rabbi Edward Reichman, MD

Shimshon (AKA Samson or Sanson) Morpurgo is a classic Italian Renaissance personality- physician, rabbi, liturgist/poet, author. Born in 1681 in Gradisca d’Isonzo, close to Gorizia, Morpurgo was brought by his father to Venice as a young boy. He spent his entire life in Italy, training to be a rabbi and physician, practicing medicine, composing prayers and poems, engaging in debate and dialogue with some of the generation’s prominent figures, and ultimately serving as the rabbi of the city of Ancona for the last twenty years of his life. While a definitive biography of Morpurgo remains a desideratum, he has been the subject of a number of dedicated essays.[1] Scholars have addressed his medical practice,[2] his philosophical work,[3] and his lengthy correspondence with Moshe Chagiz regarding the controversies involving both Shabtai Tzvi and Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto.[4] A collection of his halakhic responsa, Shemesh Tzedakah, was published posthumously by his son, Moshe Hayyim Shabtai,[5] and manuscript examples of his personal correspondence, halakhic responsa, and occasional poems can be found in various libraries.[6]

The present contribution is not primarily intended to expand upon Morpurgo’s narrative biography, though it will enhance it, but rather as a visual supplement. Here we bring to light previously unknown or little-known documents from significant chapters of his life, including his medical diploma, his semikhah and his portrait. It is a rarity to possess such a group of documents for any one figure in the pre-modern era.

Medical Diploma

Morpurgo graduated the famed University of Padua Medical School in 1700 at the age of nineteen. Padua was the first university in Europe to officially open its doors to Jewish students,[7] and hundreds of Jewish students studied there between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. A number of diplomas of Jewish graduates from this period are extant in libraries, museums and personal collections.[8] The full text of Morpurgo’s diploma is printed in Edgardo Morpurgo’s book on the Morpurgo family history,[9] but he provides neither a picture of the diploma nor any context to compare this diploma to that of other Padua medical graduates. Indeed, based on the question marks in the text and the occasional misspellings, it leads me to wonder if he had access to the original diploma when writing this text.[10] The original medical diploma, a portion of which is pictured below, is housed in the U. Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem.[11]

The diplomas of the Jewish graduates of the University of Padua Medical School possess unique features which are reflected in Morpurgo’s diploma. For example, the invocation for a standard issue medical diploma from Padua in this period, “In Christi Nomine Amen” (in the name of Christ Amen), is replaced with the non-Christian substitution, “In Dei Aeterni Nomine Amen” (in the name of the Eternal God, Amen). Morpurgo is referred to as Hebreus, typically added for the Jewish graduate. Other changes include the writing of the date as “current year,” as opposed to the typical forms of dating which included Christian reference (e.g., Anno Domini), and the location of the graduation ceremony, which was in a nondenominational venue, as opposed to a church.

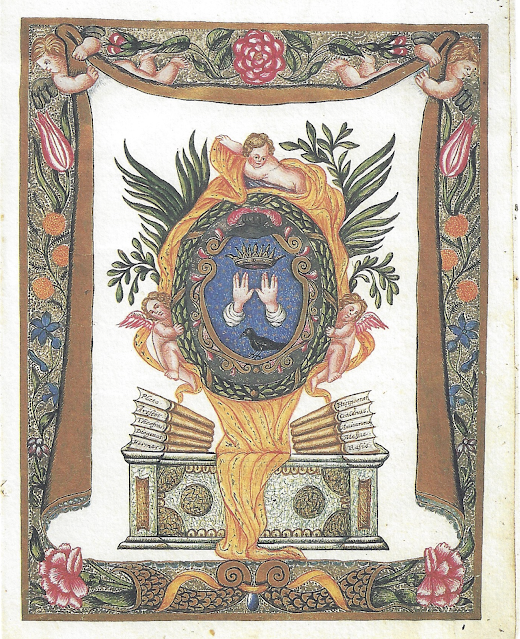

While similar to other Jewish diplomas in form, this is not the case with respect to style. In this regard, Morpurgo’s diploma stands apart from his peers. Most of the diplomas we possess of Padua graduates form this period, whether Jewish or not, are ornate elaborate works of art with magnificently illustrated borders, often including a portrait of the graduate and a family coat of arms. Indeed, Padua University hired its own staff of artists and calligraphers for this purpose. The Morpurgo family had a coat of arms- a depiction of the prophet Jonah in the clutches of the jaws of the whale- which appears in documents and tombstones of the family throughout the centuries.[12] Below are some examples:

Morpurgo’s diploma contains no portrait, no coat of arms, no illustration whatsoever. It is a simple calligraphic text.

Below are some example pages from the diplomas of two Jewish students, both of whom graduated within a year or two of Morpurgo. These diplomas were more the norm.[13]

Diploma of Lazarus De Mordis (1699)[14]

Diploma of Samuel Coen (1702)

Rabbinic Ordination (Semikhah)

As recorded in the preface to his responsa Shemesh Tzedakah, Morpurgo received his rabbinic ordination from Rabbi Yehudah Briel in 1709. Meir Benayahu records the text of the semikhah document in his article on Morpurgo.[15] Rabbi Briel was a mentor to other Padua medical graduates, including Yitzhak Lampronti.[16]

The original document is housed in the National Library of Israel[17] and is reproduced below. The ordination is handwritten on a simple piece of paper (?parchment) with no ornamentation.

This stands in stark contrast to the semikhah of Rabbi Brill himself, which is quite ornate.[18]

The unembellished nature of both Morpurgo’s medical and rabbinic certificates, especially in the historical context of Renaissance Italy, may reflect a preference for simplicity or trait of humility.

Papal Privileges

In 1730, during a severe Influenza outbreak, Morpurgo distinguished himself by providing medical services to both Jew and Christian alike. This was particularly remarkable in light of the Papal decrees prohibiting Jews from treating Christians and reciprocally forbidding Christians from being treated by Jews. At the time, this earned him the approbation and commendation of Cardinal Prospero Lambertini.[19] Lambertini would later go on to become Pope Benedict XIV (1740 –1758). In gratitude, Morpurgo and his heirs received rights to act as superintendents of merchandise arriving at the port of Ancona and intended for use in the Apostolic Palace.[20] I have discovered three extant documents issuing privileges to Morpurgo’s heirs. None of the current bearers of these documents notes the existence of the others examples.

- 1787

The earliest example of a Papal privilege for the Morpurgo family dates from 1787. The document, a picture of which appears below, was sold by Sotheby’s Auction House on December 22, 2015.[21] The catalogue entry is titled as follows: Privileges Accorded to the Heirs of Samson Morpurgo, Granted by Filippo Lancellotti, Prefect of the Apostolic Palace, Rome: 1787.

- 1793

The second example is from the year 1793. This document is not found in any auction house or museum, but rather on the ancestry research website, MyHeritage.com, accompanying a Morpurgo family tree. While it is not as high quality a reproduction, it is clearly of the same origin as the other two issuances, similar to the third example below. These type of ancestry sites, which include elaborate family trees, often with accompanying historical documents (photos, paintings, etc.), represent an untapped resource for historical research. I will leave it to scholars to debate the use of such material, which may be unprovenanced.

- 1794

The final example comes from the Umberto Nahon Museum (Jerusalem).[22]

Cardinal Lancellotti, the Prefect who issued the first document above, died in 1794. The latter two were issued by Giuseppe Vinci, assumedly another Prefect of the Apostolic Palace. All three of the documents above were issued under the auspices of Pope Pius VI (1775-1799). It is quite possible that more such documents will surface in the future.

Portrait of Shimshon Morpurgo

As mentioned above, the diploma of Morpurgo bears no illumination, and thus, no portrait, as is found in the diplomas of some other Jewish graduates. Be it for principled or financial reasons, Morpurgo elected not have his portrait adorn his certificate of medical school completion. He did however sit for a portrait later in life,[23] which represents his rabbinic pursuits exclusively, without allusion to his medical practice.[24]

He is pictured at his desk, with his hand on an open Hebrew book. The top line, spanning across both pages is legible, and reads, “ach bi-zelem yithalekh ish,” a phrase from Tehillim (39:7) with kabbalistic overtones.

The remaining open pages of the book consist of scrawled lines. Inscriptions in Hebrew characters can be found in the works of European artists of the early modern period.[25] Behind Morpurgo are shelves lined with Hebrew books. Some of the titles are legible, including Rambam and Levush, though I cannot make out the others.

The artist for the Morpurgo portrait is not known, though it is remarkably similar to the portrait of another rabbi physician of this period, Chakham David Nieto (1654- 1728).[26]

There are so many similarities in fact – the curtains, the chair, the bookshelf,[27] the desk, the quill, the book with a legible Hebrew top line- that I am inclined to suggest that they were either drawn by the same artist, or at the very least one was directly inspired by the other.[28]

The book under Nieto’s hand is an accurate representation of his own Mateh Dan, published in 1714, while the book under Morpurgo’s hand does not appear to be that of his own authorship.[29] This may explain why Nieto is holding a quill as if writing the text before him.

The artist for Nieto’s portrait is David Estevens, a Dutch Jew. Though we do not know the exact date of Nieto’s portrait, Landsberger writes that inasmuch as the portrait shows certain books written by him in 1714 and 1715, it follows that the portrait must have been painted at a time subsequent to then.[30] He does not identify the books to which he refers. A number of books of Nieto’s clearly appear in the portrait. Mateh Dan was published in 1714 and Pascalogia in 1702. Esh Dat was published in 1715, and though not clearly completely visible, the word “Dat” in English appears on a book resting on its side on the bookshelf. Perhaps Landsberger was referring to this. What Landsberger did not know, is that there is a more obtuse reference to another work of Nieto’s which may bring the date of our portrait forward by a few years. On the notebook behind the book Mateh Dan appears the word “Noticias.” Cecil Roth suggests that this one word was used by Nieto to cleverly claim authorship of an anonymously published controversial work beginning with the same word.[31] This work was published in 1722. Thus, this portrait must have been drawn between 1722 and 1728.

While there is no way to determine the exact year of Morpurgo’s portrait, we can likewise limit it to within a certain time period based on the internal aspects of the portrait. The card sitting on Morpurgo’s desk displays the name of the city Ancona, though unfortunately I cannot make out the other words on the card. It is in Ancona that Morpurgo settled for the later portion of his life, marrying the daughter of Rabbi Fiametta, the rabbi of Ancona, whose position he filled after the latter’s death. Thus, it is fair to assume that the portrait was drawn somewhere between 1710[32] and 1740.

Parenthetically, this portrait depicts Morpurgo without a beard. Recent discussions have addressed the issue of the beardless rabbis of the Renaissance period and have included Morpurgo’s portrait.[33]

Portrait of Morpurgo’s Son

While researching the portrait of Shimshon Morpurgo, I came across a portrait identified as Joseph Leon Morpurgo (d. 1786), the son of Shimshon.[34]

What makes this portrait of particular interest is less its connection to his father than its correlation with Joseph’s ketubah, presently in the Jewish Theological Seminary Library.

This spectacularly ornate renaissance ketubah is unique in that it contains miniature illustrations of a bride and groom.

Ketubah of Morpurgo’s son Yosef

Ancona 1755[35]

Are these simply generic representations of a bride and groom, or are they actual portraits of the wedding party? A “head” to “head” comparison between the portrait and the ketubah may provide some insight.

I will leave it to the reader to decide on the extent of the similarities. The Morpurgo coat of arms also appears on the top of the ketubah.[36]

Morpurgo’s Participation in Weddings and Circumcisions

In addition to his scholarly exploits, we have record of Morpurgo’s social activities as well. Like many of his Jewish Italian Renaissance peers, he wrote occasional poetry, including for the wedding of Shabtai Marini, a fellow medical graduate of the University of Padua, though some fifteen years earlier.[37] Marini has also been identified as a rebbe of Ramchal, though evidence is scant,[38] and translated Ovid’s Metamorphosis into Hebrew.[39]

Morpurgo also wrote a wedding poem for another Marini family wedding in 1721, the union of Benjamin ben Matzliach Rava and Elena bat Gemma and Isaac ben Solomon me-Marini.[40]

We also have record of Morpurgo serving as a witness for the Ketubah of two weddings in the year 1722,[41] with one example below.[42]

We can compare Morpurgo’s signature on the ketubah to that found on the inside cover of Morpurgo’s personal copy of Rashba’s commentary on Kiddushin.[43]

A Pinkas Mohel, or circumcizor’s ledger, from his time (1705- 1736) documents his involvement in varying capacities in the circumcisions of the time, including those of his children.[44]

Conclusion

Shimshon Morpurgo is one of the more remarkable figures in Jewish history, a true Renaissance personality. From an archival perspective, he may possibly be the only pre-Modern Jewish figure for whom we possess a copy of his rabbinic ordination, medical diploma and portrait, in addition to the other notable material included here. These visual supplements to Morpurgo’s biography will hopefully further enhance our appreciation of his illustrious life.

[1] On Morpurgo, see Edgardo Morpurgo, La Famiglia Morpurgo di Gradisca sull’Isonza 1585-1885 (Premiata Societa Cooperativa: Padova, 1909), 32–34, 65–69, 77, 104; Yeshayahu Sonne, “Letter Exchange Between R. Moshe Chagiz and R. Shimshon Morpurgo,” (Hebrew) Kobetz al Yad, 12 (1937), 157–96; M. Wilensky, “On the Rabbis of Ancona,” (Hebrew) Sinai, 25 (1949), 68–75; M. Benayahu, “Rabbi Shimshon Morpurgo,” (Hebrew) Sinai 84 (5739), 134-165; David Ruderman, “Kabbalah, Science and Christian Polemic: The Debate Between Samson Morpurgo and Solomon Aviad Sar Shalom Basilea,” in his Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe (Yale University Press: New Haven, 1995), 213-228; A. Salah, La Republique des Lettres: Rabbins, Ecrivains et Medecins, Juifs en Italie au XVIIIe Siecle (Brill: Leiden, 2007), 455-460. On his graduation from the University of Padua, see A. Modena and E. Morpurgo, Medici e Chirurghi Ebrei Dottorati e Licenziati nell’Università di Padova dal 1617 al 1816 (Forni Editore: Bologna, 1967), 62, n. 147. In the eighteenth century, the Inquisition in Mantua routinely confiscated Hebrew books for expurgation. Some of Morpurgo’s books were confiscated in 1732, only to be returned six years later. See S. Simonsohn, The History of the Jews in the Duchy of Mantua (Kiryath Sepher: Jerusalem, 1977), 694, n. 398.

[2] Abraham Ofir Shemesh, “Two Responsa of R. Samson Morpurgo on Non-Kosher Medicines: Therapy vs. Jewish Halakhic Principles,” Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 18:52 (Spring 2019), 3-16. In his introduction to his philosophical work Eitz Ha-Da’at (Venice, 1704), 3b, Morpurgo mentions his plans to write a manual on the laws of treifot which would include extensive anatomical discussions and illustrations. We have no record of this idea ever coming to fruition. Chaim Meiselman wrote a brief article for the University of Pennsylvania Library blog (Pennrare.wordpress.com) entitled, “An Illustrated Manuscript for Terefot: CAJS Rar Ms 480,” (February 27, 2019). Here he discusses an anonymous Italian manuscript on treifot with detailed illustrations and anatomical notes. Could this somehow be related to Morpurgo?

[3] Ruderman, op. cit.

[4] See Sonne, op. cit; Yaakov Shmuel Speigel, “The Beginning of the Ramchal Polemic: Four New Letters from the Manuscripts of Rabbi Shimshon Morpurgo,” (Hebrew) HaMa’ayan 231 (Tishrei, 5780), 324-355; idem, “The Ramchal Polemic: The Complete Letter Sent by R’ Moshe Chagiz to R’ Shimshon Morpurgo,” (Hebrew) Da’at 89 (2020), 371-404. I thank Eliezer Brodt for this source.

[5] (Vendramin: Venice, 1743).

[6] See the National Library of Israel’s International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts, https://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/en/manuscript, s. v., “Samson Morpurgo.”

[7] See E. Reichman, “The Valmadonna Trust Broadsides: A Virtual Reunion for the Jewish Medical Students of the University of Padua,” Verapo Yerapei 7 (2017): 55-76.

[8] See E. Reichman, “The ‘Doctored’ Medical Diploma of Samuel, the Son of Menasseh ben Israel: Forgery or ‘For Jewry’,” Seforim Blog (here), March 23, 2021; idem, “Confessions of a Would-Be Forger: The Medical Diploma of Tobias Cohn (Tuvia HaRofeh) and other Jewish Medical Graduates of the University of Padua,” forthcoming in K. Collins and S. Kottek, eds., Ma’ase Tuviya (Venice, 1708): Tuviya Cohen on Medicine and Science (Jerusalem: Muriel and Philip Berman Medical Library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2019), in press.[9] Morpurgo, op. cit., 65-68.

[10] For example, the name of one of the witnesses is written in the book as “Sabbetteo. Vith [?] Marini hil.” while it appears clear in the original- Sabbatheo Vita Marini Phil (short for philosophy and medicine degree).

[11] I thank Dr. Andreina Contessa, former Chief Curator of the museum, for kindly providing me with the images of this diploma.

[12] The pictures of stone below appear on the cover of Marjetka Bedrac and Andrea Morpurgo, The Morpurgos, the Descendants of the Maribor Jews (Center Judovske Kulturne Dediscine Sinagoga, 2018). The fourth image appears at the top of a ketubah for the wedding of Zechariah ben Shemariah Morpurgo and Luna bat Isaac ben Shemariah Morpurgo in Venice on Wednesday, 14 Nisan 5472 (April 9, 1712). The item was auctioned by Sotheby’s, Important Judaica (December 19, 2018), item 153. There is an author named Michael Morpurgo who wrote a book titled, “Why the Whales Came.” I wonder if this is more than coincidence.

[13] For further discussion of these students and their diplomas, see Reichman, “Confessions,” op. cit.

[14] If the graduate requested, a portrait would be drawn in the medallion. There was an addition fee for this service

[15] Benayahu, op. cit., 157.

[16] For more on Briel and his circle of medical students, see Reichman, “Valmadonna,” op. cit.

[17] System n. 990001800790205171.

[18] Venice (1677) JTS B (NS) PP489

[19] The text is preserved in Edgardo Morpurgo, op. cit., 69.

[20] Awarding a person and his heirs for exceptional behavior was common practice in Europe at this time. Other Jewish families benefitted from this practice. For example, Benjamin Ravid writes, “In 1616, in accordance with the privilege granted by the Council of Ten 150 years earlier to David Mavrogonato of Crete that in return for his untiring services to Venice he and his heirs were, among other favors, to be exempted from the special Jewish distinguishing sign, the Cattaveri granted the request of Elie Mavrogonato of Crete to be allowed to wear a black capello.” See Benjamin Ravid, “From Yellow to Red: On the Distinguishing Head-Covering of the Jews of Venice,” Jewish History 6:1-2 (1992), 179-210, esp. 196. Ravid mentions other family members who benefitted from these privileges.

[21] http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/important-judaica-n09447/lot.14.html (accessed April 17, 2021).

[22] Item number: ICMS-EIT-0825.

[23] C. Roth, The History of the Jews in Italy (Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia, 1946), opposite p. 401. Roth identifies the portrait as an oil painting in the possession of the Morpurgo family. I have as yet been unable to identify the location of the original work. I have consulted museums, libraries and members of the Morpurgo family to no avail. All the copies of this portrait I have identified all seem to be from this one source. I have found no discussion or source detailing the whereabouts of the portrait or the identity of its author.

[24] A copy of this picture is pinned to the inside cover of Morpurgo’s original medical diploma in the U. Nahon Museum.

[25] Pawel Maciejko has recently added to the scholarship on this topic, which has included studies on the works of Rembrandt. See P. Maciejko, “A Portrait of the Kabbalist as a Young Man: Count Joseph Carl Emmanuel Waldstein and His Retinue,” Jewish Quarterly Review 106:4 (Fall 2016), 521-576, esp. 529-537. Maciejko notes that, “While Hebrew inscriptions were commonplace in Western paintings, representations of Hebrew books were rare.”

[26] On Nieto’s portrait, see Macienko, op. cit., 533-536; OntheMainline Blog, “David Nieto, an Art Mystery and the Joys of Digitized Books” (October 9, 2009) http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2009/10/david-nieto-art-mystery-and-joys-of.html (accessed April 17, 2021); F. Landsberger, “The Jewish Artist Before the Time of Emancipation,” Hebrew Union College Annual 16 (1941), 321-414, esp. 387-388.

[27] A few books on the shelf of Nieto’s portrait appear to bear a title, though I cannot decipher them.

[28] The clarity and detail of the Nieto portrait appears far superior, but this may simply be a reflection of the quality of the reproduction.

[29] The phrase from Tehillim does not appear in his work, Eitz ha-Da’at, or in his responsa, Shemesh Tzedakah, published posthumously by his son, Moshe Hayyim Shabtai.

[30] According to Landsberger, op. cit., the reproduction here in mezzotint, done by I. MacArdell, did not appear until 1728, the year of Nieto’s death. The original oil painting upon which this work is based is lost today.

[31] See OntheMainline blog, “David Nieto, an Art Mystery and the Joys of Digitized Books” (October 9, 2009) http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2009/10/david-nieto-art-mystery-and-joys-of.html (accessed April 17, 2021); Cecil Roth, “The Marrano Typography in England,” The Library 5:2 (1960), 118-128, esp. 121-122.

[32] According to Benayahu, op. cit., 139, the earliest documentation placing Morpurgo in Ancona dates from July, 1711.

[33]See http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2011/01/beards-and-beardlessness-in-italian.html (accessed April 17, 2021). Here the author writes, “apparently the native Jews of Salonica were scandalized by the closely trimmed beards of the Francos who lived among them. They demanded that they grow them or be expelled. The situation of the ex-pat Italians came to the attention of the Italian rabbis, including one of the foremost ones, Samson Morpurgo (Shemesh Tzedakah #61). Morpurgo interceded on their behalf attempting to prevent the Salonica community from expelling those not sporting a full beard. It is pointed out that Morpurgo himself, as per the above portrait, was beardless.”

There is a portrait on myheritage.com which is identified as being that of Dr. Samson Morpurgo. Attempts to contact the curator of the site to learn more about the portrait were unsuccessful.

It depicts an older man with a salt and pepper beard. This man is dressed in garb similar to Morpurgo and is likewise seated at a desk with a feather and quill. I have no additional information to corroborate this identification and have seen no reference to this portrait elsewhere. If indeed verified, this would not only add to our visual history, it would also alter the discussion about Morpurgo’s beardlessness.

[34] The portrait is found on the MyHeritage.com website. Attempts to contact the curator of the site to learn more about the portrait were unsuccessful.

[35] JTS Library Ketubah 5 record # 265985. I thank Sharon Liberman Mintz for bringing this ketubah to my attention.

[36] Apparently as both the bride and groom were members of the Morpurgo family only one coat of arms was included.

[37] David Kaufmann Collection of Medieval Hebrew manuscripts in the Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, n. 580, p. 21. I thank Kinga Devenyi from the Kaufmann Collection in Budapest for providing a copy of this poem. While the poem is unsigned, Benayahu provides definitive proof that Morpurgo is the author. For additional information on Marini and this poem, see M. Benayahu, “Rabbi Avraham Ha-Kohen Mi-Zanti U-Lehakat Ha-Rof ’im Ha-Meshorerim Be-Padova,” Ha-Sifrut 26 (1978): 108-40, esp. 110-111.

[38] See OntheMainline blog (October 20, 2010), http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2010/10/ramchals-rebbe-rabbi-sabbato-marini-of.html (accessed April 17, 2021). There, the rebbe of Ramchal, as well as the picture below are identified as Rabbi Dr. Shabtai Aharon Chaim Marini (1685-1762).

According to Laura Roumani, whose dissertation is on Shabtai Hayyim Marini, both the picture and rebbe of Ramchal are Shabtai Hayyim Marini (1662-1748). In addition, according to Roumani, “Shabbetay Aharon Hayyim Marini is not the one born in 1685 who died in 1762. That is Shabbetay son of Aharon Marini who got his degree in medicine in 1705. He belongs to another lineage of the family. Shabbetay Aharon Hayyim Marini passed away in 1809 and was a rabbi in the Spanish synagogue of Padua. He was the son of Shelomoh Marini son of Shabbetay Hayyim and the father of Armellina Stella Rahel Marini who married Avraham Sevi HaLevi who inherited all the autographs of Shabbetay Hayyim Marini.” See Laura Roumani, “Le Metamorfosi di Ovidio nella traduzione ebraica di Shabbetay Hayyim Marini di Padova” [Ovid’s Metamorphoses translated into Hebrew by Shabtai Ḥayim Marini from Padua] (PhD diss., University of Turin, 1992). See also L. Roumani, “The Legend of Daphne and Apollo in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Translated into Hebrew by Shabbetay Ḥayyim Marini” [in Italian], Henoch (Turin University) 13 (1991): 319–335.

[39] Joseph Almanzi composed an ode to Marini in his Nezem Zahav:

[40] JTS Ms. 9027 V2:29. The poem is signed זה שמ”י לעלם and the author is not identified in the JTS catalogue. As per correspondence with Laura Roumani, “The author is Shimshon Morpurgo (who used to sign as Shmi, shin mem being the initials of his name). Elena was the daughter of Gemma second wife of Yishaq Marini, Shabbetay Hayyim Marini’s father. The wedding took place after 1721 (Yishaq was deceased). Though Shelomoh Marini is mentioned, he was not Yishaq Marini’s father. Yishaq was the son of Shabbetay Marini the doctor, brother of Shelomoh.”

[41] National Library of Israel, system number 000301332 and system number 004092777.

[42] system number 004092777. The wedding of Shmuel Moshe Hakohen and Diamante Hakohen.

[43] This sefer is part of the Shimeon Brisman Collection in Jewish Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. http://omeka.wustl.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/brisman/item/6997 (accessed April 16, 2021).

[44] See University of Pennsylvania Library, CAJS Rar Ms 503 (https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9969495443503681). The catalogue notes references to Morpurgo on pages 16r and 24r. There is an additional mention of Morpurgo on page 32v (item 167), which is pictured here. The name Morpurgo spans across two lines.