Response to Criticism Part 4; Rabbi Zvi Yehuda and the Hazon Ish

Response to Criticism Part 4; Rabbi Zvi Yehuda and the Hazon Ish

Marc B. Shapiro

Continued from here.

1. In Limits,p. 14 n. 55, I write

I should call attention to a significant philosophical and halakhic point which appears to have gone unnoticed. The Vilna Gaon (R. Elijah b. Solomon Zalman (1720-97) apparently believed that the First and Second Principles are the only true Principles in Judaism. According to him, one who believes in God’s existence and unity, despite his other sins, is regarded as a Jew in good standing and he is thus able to be included in a minyan (quorum for public prayer). None of the numerous discussions regarding whether a Sabbath violator maybe in included in a minyan seems to have taken note of the Gaon’s comment, which appears in his commentary on Tikunei Zohar, 42a.

Grossman writes:

Apparently, concludes Shapiro, since the Gaon cites only idolatry as invalidating prayer and does not cite the rest of the Thirteen Principles, he is disputing Rambam’s classification of the others as binding fundamentals. However, this source has no bearing on the Principles. The Gaon’s comment refers to counting one for a minyan and to having one’s prayer accepted by God. He is clearly not referring to the Principles, since [in his commentary to Tikunei Zohar] he includes in the metaphor of the scorpion the sin of consorting with gentile women, which is unrelated to any Principle. (p. 48)

The first thing to note is that I never said that the Vilna Gaon disputed “the Rambam’s classification of the others [other Principles] as binding fundamentals.” Of course the Gaon held that people must believe that there is prophecy, that God gave the Torah, that there will be a Messiah, etc. But that is not what I am referring to when I say that for the Gaon the First and Second Principles are the only true Principles in Judaism. As I explain, for the Rambam the Thirteen Principles are special in that if you deny any of them you are to be regarded as having removed yourself from the Jewish people. When the Gaon makes the fascinating comment that belief in the First and Second Principles are enough to be regarded as part of the Jewish people, thus enabling one to be counted in a minyan, this means that as far as he is concerned (in this passage at least), only these beliefs qualify as Principles in the absolute sense that denial of them removes you halakhically from the Jewish people. If I were writing the book today, I would say that the Gaon focuses on three Principles, since he includes belief in the unity of God and an affirmation of God’s corporeality (Principle no. 3) certainly violates God’s unity.

I have to say, however, that while the Gaon’s comment is of great importance when it comes to the issue of Sabbath violation, I am no longer sure about the correctness of my larger point. It could just as well be that when the Gaon derives from the passage in Tikunei Zohar that if you believe in God and His unity, despite your other sins, you are still a Jew in good standing, it does not necessarily mean that these are the only true Principles. It could be that he is merely explicating the meaning of the passage in Tikunei Zohar, which relates to God, but that if it was a different passage he could have spoken about different principles, for example, as long as you believe in the Messiah and the resurrection even if you sin you are still a Jew in good standing. Here is some of what the Gaon writes:

כ”ז שמאמין באחדותו ית’ אפי’ עובר כמה עבירות אינו מומר לכל התורה ואעפ”י שחטא ישראל הוא ומצטרף למנין כמ”ש עבריין כו’ ונכלל תפלתו בכלל ישראל . . . אבל עקרב הוא המודה בעבודת כוכבים ומשתחוה לאל אחר וכן בבת אל נכר אז הקוץ ח”ו מסתלק מצדו וזהו פירוד הגמור וז”ש ואיהו פוסק וברח כו’ ר”ל יוסף במדרגתו ומסתלק הקב”ה ממנו כלל וכלל ואין תפלתו עולה כלל

In the Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7, the Rambam says that if you believe that God has a physical form you are a heretic, and Rabad famously defends those who did not know any better. According to Rabad, although these people are wrong they are certainly not heretics because of their mistake. Regarding this dispute there is R. Hayyim Soloveitchik’s famous statement in defense of the Rambam’s position that “one who is nebech an epikores is still an epikores.”[1]

In Limits I referred to the Hazon Ish’s opinion that the Rambam actually agrees with Rabad when dealing with a heretic who does not know any better. I further note, in agreement with R. Hayyim, that the Hazon Ish’s suggestion cannot be correct, and the Rambam, Guide 1:36, specifically rejects the Hazon Ish’s point. In fact, R. Kafih thinks that the Rambam saw Rabad’s criticism of what he wrote in the Mishneh Torah, and the end of Guide 1:36 was written in response to Rabad and is the Rambam’s defense of his position that faulty education or simply ignorance is no defense when it comes to belief in God’s corporeality.[2] In truth, even if we did not have this chapter of the Guide, the Hazon Ish’s position cannot be sustained, as it is in opposition to the Rambam’s entire conception of immortality which is a natural process. Thus, there is no room to raise questions about “fairness” or why does God not judge an ignorant person mercifully and grant him a share the World to Come if through no fault of his own he believes that God has a physical form.

Grossman, on the other hand (p. 49), claims that a close reading of the Guide supports the Hazon Ish’s position that someone who does not know any better, and who has no one to teach him, is not to be regarded as a heretic. Suffice it to say all scholars of the philosophy of the Rambam agree with R. Hayyim in this matter. Furthermore, the issue is not whether we regard someone as a heretic or not. There could be societal reasons that determine whether or not one is to be regarded as such. The dispute between the Rambam and Rabad is regarding someone who doesn’t know any better and denies a principle of faith, does such a person have a share in the World to Come? It is clear, as Rabad recognized, that according to the Rambam the answer is no. That is why I wrote that when the Hazon Ish explained the Rambam to really be agreeing with Rabad—that an unwitting heretic has a share in the World to Come—that this approach should be seen as in opposition to the Rambam’s position, even though the Hazon Ish was offering his approach as an interpretation of the Rambam.[3]

Grossman then writes (p. 49 n. 65): “In another example of the same hubris towards a giant of Torah scholarship, Shapiro, on p. 37, asserts that the Chazon Ish’s acceptance of Torah She-be’al Peh as having Divine authority (Iggeros 1:16 [should be 15]) is disputing Rambam. Chazon Ish there is merely emphasizing Rambam’s Eighth Principle, but Shapiro claims that Chazon Ish actually ‘added a new dogma.’”

The reader who turns to my book, p. 37, will find that contrary to what Grossman states, I do not mention anything about Torah she-be’al peh. The issue I was concerned with is the authority of Aggadah. In one of his most often quoted letters (Kovetz Iggerot Hazon Ish, 1:15), the Hazon Ish writes that all aggadot have their origin in the sages’ prophetic power, and one who denies this is a heretic.

משרשי האמונה שכל הנאמר בגמ’ בין במשנה ובין בגמ’ בין בהלכה ובין באגדה, הם הם הדברים שנתגלו לנו ע”י כח נבואי שהוא כח נשיקה של השכל הנאצל, עם השכל המורכב בגוף . . . נרתעים אנחנו לשמוע הטלת ספק בדברי חז”ל בין בהלכה בין באגדה, כשמועה של גידוף ר”ל, והנוטה מזה הוא לפי קבלתנו ככופר בדברי חז”ל, ושחיטתו נבילה, ופסול לעדות, ועוד, ולכן נגעו דבריך בלבי

Incidentally, in the published version of the letter it has

והנוטה מזה הוא לפי קבלתנו ככופר כדברי חז”ל

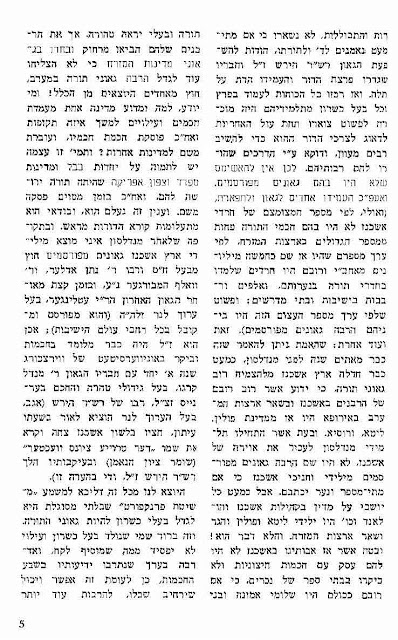

Here is the section of the actual letter of the Hazon Ish where you can see that it should read ככופר בדברי חז”ל.

Searching on Otzar haChochma, I see that almost everyone who cites this passage corrects the printing error.

It is with regard to this statement about aggadah, and this statement alone, that I spoke of a new dogma—which can perhaps already be seen in the Maharal if not earlier—that is not held by the Rambam who, together with the entire geonic and medieval Sephardic rabbinic tradition, did not have such a view about the binding nature of all aggadot. The reader of Grossman’s article who does not examine my book would think that I claimed that the Rambam did not believe that Torah she-be’al Peh has divine authority. Yet the difference of opinion between the Rambam and the Hazon Ish is over a different matter, namely, what is included in Torah she-be’al Peh. In fact, this is not really a dispute between the Rambam and the Hazon Ish, but a dispute between two traditions regarding how to understand Aggadah.

Incidentally, in the Hazon Ish’s letter just mentioned, in discussing the difference between prophecy and ruah ha-kodesh, he says something directly in opposition to the Rambam’s view.

אבל יש הבדל יסודי בין נבואה לרוה”ק. נבואה, אין השכל המורכב של האדם משתתף בה, אלא אחרי התנאים הסגוליים שנתעלה בהם עד שזכה לזוהר נבואי, אפשר לו להיות לכלי קולט דעת. . . , מבלי עיון ועמל שכלי, אבל רוה”ק היא יגיעת העיון ברב עמל ובמשנה מרץ, עד שמתוסף בו דעת ותבונה בלתי טבעי

In the published version of the letter there are three periods after the word דעת which I have underlined in. Usually when there are three periods it means that something has been removed from the letter, but in this case nothing has been removed. In fact, in the original letter there are only two periods, followed by a comma, and I don’t know why the Hazon Ish used these periods.

Continuing with Grossman, he sees it as obvious that the Hazon Ish’s opinion regarding an unwitting heretic is exactly what the Rambam held, and in support of this he points to Hilkhot Mamrim 3:1-3. Here the Rambam states that Karaites, who were raised with heretical beliefs and don’t know any better, are not to be judged like the original Karaite heretics who consciously rejected the Oral Law. With those who don’t know any better the Rambam counsels “not to rush to kill them,” but to draw them close to Torah with words of peace. (The words “not to rush to kill them” were removed from some printings.)

Does this passage have any relevance to the Rambam’s view of unintentional heresy? The answer is no, as here the Rambam is only counseling tolerance when dealing with Karaites who don’t know any better. He is only concerned with how we should relate to them. Rather than hating them and hoping for their destruction, which is normally the case with regard to heretics, the Rambam tells us that we should relate to the Karaites in a positive way and attempt to convince them to abandon their mistaken path. However, from the theological perspective, a heretic has no share in the World to Come and cannot be exculpated based on the argument that he does not know any better. I make this argument in Limits, p. 12, and it is also affirmed by R. Chaim Rapoport.[4]

Not only is this the peshat in the Rambam, but no other understanding works within the context of his philosophical system. That is, the Rambam’s entire philosophical understanding of the World to Come does not work with the notion that an unwitting heretic can also have a share in the World to Come. Any interpretations that assume otherwise are simply not in line with the Rambam’s approach, an approach that was well understood by both his supporters and opponents who argued at great length about this matter. It was also recognized by R. Hayyim who knew the Guide of the Perplexed well. R. Velvel, in discussing the passage in Hilkhot Mamrim pointed to by Grossman, stated exactly what I have just explained. Here are his words as quoted by R. Moshe Sternbuch[5]:

.הרי מפורש בדבריו [הרמב”ם] דמה שהוא אנוס מועיל רק לענין שראוי להחזירם בתשובה ולמשכם לחזור לאיתן התורה, אבל כל זמן שלא חזרו הם מומרים באונס, ושמם מומרים ואפיקורסים

If I were to argue in the fashion of Grossman, I could say that by asserting that the Hazon Ish is simply following what the Rambam says in Hilkhot Mamrim, that Grossman shows disrespect to R. Hayyim and R. Velvel, by not even seeing their positions as worthy of discussion.

There is a parallel to what we have been discussing elsewhere in the Mishneh Torah. In Hilkhot Avodah Zarah 2:5 the Rambam states that the repentance of heretics (minim) is never accepted. Yet in Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:14 the Rambam states that heretics who repent have a share in the World to Come. The Rambam was asked about this apparent contradiction and he replied that indeed there is no contradiction.[6] In Hilkhot Avodah Zarah he is speaking about how the Jewish community is to relate to heretics. As far as the community is concerned, even if a heretic repents the community is not to accept him, as one can never be sure that his repentance is authentic. However, Hilkhot Teshuvah is referring to the heretic’s relationship with God. As far as God is concerned, a true repentance is always accepted. (I don’t know of anyone today who accepts the Rambam’s opinion in this matter. If, say, a leading atheist philosopher or Reform rabbi decided to become Orthodox, not only would the community accept him, but people would make a very big deal of this and he would become a sought-after speaker at Orthodox synagogues.)

Grossman writes:

In an attempt to list various authorities who took issue with Maimonides, Shapiro tells us that “[i]n Abarbanel’s mind, only limited attention . . . should be paid to Maimonides’ early formulation of dogma, and it would certainly be improper to make conclusions about his theological views on the basis of a text designed for beginners.” (p. 50)

My citing of Abarbanel on p. 7 of my book has nothing to do with authorities who took issue with Maimonides. The mention of Abarbanel is with reference to my discussion about how the Thirteen Principles do not appear as a unit in the Mishneh Torah or the Guide, and in this regard I cited Abarbanel who writes as follows in Rosh Amanah, ch. 23:

This explains why he did not list these principles in the Guide, in which he investigated deeply into the faith of the Torah, but mentioned them rather in his Commentary on the Mishnah, which he wrote in his youth. He postulated the principles for the masses, and for beginners in the study of Mishnah, but not for those individuals who plumbed the knowledge of truth for whom he wrote the Guide.

Following his misunderstanding of my point, Grossman spends the next page explaining that Abarbanel accepts the truth of the Rambam’s Principles, a fact that I never denied. However, Abarbanel also believes that for the most profound understanding of the Rambam’s theological views, one needs to turn to the Guide. As I mention in the book, pp. 32-33, Abarbanel also does not accept the Maimonidean concept of Principles of Faith.

Regarding the Rambam positing Thirteen Principles of Faith, which I claimed is a novelty of the Rambam, let me cite R. Moses Sofer who says exactly this.[7]

י”ג העיקרים המציא הרמב”ם שהוא היה הממציא הראשון בזה, ואשר לפנים לא ידענום

Grossman’s final comment in the first half of his review is as follows (p. 52):

Another example of Shapiro’s proofs that Rambam’s theology differs from one work to another is the following. In his Commentary on the Mishna, Rambam states that “lack of belief in any of the Principles makes one a heretic.” [Quotation from Limits, p. 8] Yet, in his Mishneh Torah, he writes (Shapiro’s translation): “Whoever permits the thought to enter his mind that there is another deity besides God violates a prohibition, as it is said: You shall have no other gods before me . . . and denies the essence of religion – this doctrine being the great principle on which everything depends.”

This proves, says Shapiro, that one is not considered a heretic for such thoughts since the Rambam does not say that one who holds these beliefs is a heretic. However, the very source he adduces clearly says the opposite. The words kofer be-ikar,[8] used by the Rambam in this quotation, are a synonym for “heretic,” even according to Shapiro’s rendition of the words as one who “denies the essence of religion.”

If the Rambam writes that recognition of God as the source of all existence is a Principle upon which all of Judaism stands, it is obviously a Principle of faith.

I don’t think that anyone who reads these paragraphs will have a clue as to what my point was. What I noted is that in the Commentary on the Mishnah, in discussing Principles of Faith, Maimonides speaks of belief (or knowledge, depending on how you translate). This is a mental state. However, in Hilkhot Teshuvah, in discussing what makes someone a heretic, Maimonides writes: “One who says”.[9] In other words, he speaks of verbalizing one’s heresy publicly, not simply belief. If all we had was Hilkhot Teshuvah, one could conclude that even one who has heretical ideas, but conducts himself as a good Jew publicly, does not lose his share in the World to Come.

In the book I then turned to Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah 1:6 which speaks about one who imagines that there is another God, and by doing so denies the essence of Judaism. A similar comment can be found in Hilkhot Ishut 8:6 where the Rambam writes: “For the sin of idol worship is so great that even when a person thinks of serving [idols] in his heart [without acting upon it] he is considered wicked.” I noted that while a person who believes something heretical like this has, in his mind, denied the essence of Judaism, as long as his heresy is not publicly voiced he apparently is not to be regarded as a complete heretic with all the communal implications this implies. (For example, if you found someone’s private diary which revealed that he denied certain basic principles of faith, as far as the community is concerned he would apparently remain a Jew in good standing as he never publicized his heresy. But he would still have no share in the World to Come.)

It is clear that the Rambam believes that one who affirms a heretical doctrine loses his share in the World to Come, no matter what the reason he does so. But we need to ask why the Rambam specifically uses the formulation of “one who says”. The easiest answer is that he was simply adopting, and making wider use of, the language found in the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1, which also categorizes two types of heresy by using the expression “one who says.”

It makes sense to assume that only one who publicly verbalizes his heresy is to be treated as a heretic by the larger community, but despite the language in the Mishnah, I think many will still wonder why in Hilkhot Teshuvah, which speaks of losing one’s share in the World to Come, Maimonides also uses the language “One who says.” I don’t have an answer to this question. All I did in the book was note that the Rambam’s formulation in the Mishneh Torah is different than what he writes in the Commentary on the Mishnah. Although I have found some rabbinic discussions of this problem, I am surprised that none of the major commentaries take up the issue of why the Rambam uses the word האומר in defining heresy. It seems that they would agree with R. Uri Tieger[10] who writes:

לאו דוקא האומר אלא אפי’ חושב כן ולא מוציא בפיו

It is noteworthy, though, that immediately following these words R. Tieger offers an alternative approach which speaks to the very point I was discussing

וי”א דאף דכל הני שרשי איסורם הוא במחשבה מ”מ לא נחתם עונם עד כדי שיקראו מינים ואפיקורסים עד שיוציאו הדברים בפיהם

R. Avraham Gottesman also raises the issue, and he too sees the Rambam’s formulation in the Mishneh Torah as possibly significant.[11]

‘האומר . . . הרי שלא הזכיר גם שם ממחשבה. ואולי תנא ושייר או לא רצה להחזיקו לאפיקורס ע”י העדר אמונת מחשבה כי רבות מחשבות בלב איש שאין בהם ממש וגם רוב מחשבות אין הקב”ה מצרפן למעשה חוץ ממחשבות ע”ז כדאיתא בגמ

All this is important and worth exploring. But let us return to Grossman, who again attempts to make me look like a fool. He states: “This proves, says Shapiro, that one is not considered a heretic for such thoughts since the Rambam does not say that one who holds these beliefs is a heretic.” Grossman makes this false statement based on my discussion on pp. 8-9. Yet if he had only turned to page 13, at the end of my discussion of this matter, he would have found that I write as follows:

We must therefore conclude that Maimonides’ use of the words “one who says” in describing a heretic is only in imitation of Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:1 where the same formulation is found, and not too much should be read into this. One who believes in a corporeal God or in the existence of many gods, even without saying so publicly, is indeed a heretic as far as Maimonidean theology is concerned. Such a one will not face any penalties from an earthly court, but he is certainly denied a share in the world to come.

In other words, my conclusion is the exact opposite of what Grossman attacks me for (and is indeed in line with Grossman’s own opinion).

As for the word האומר as opposed to המאמין, R. Nissim of Marseilles writes as follows with reference to the usage of the term האומר in Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1.[12]

והאומר אין תורה מן השמים, ולא אמר “המאמין” כי באמירה לבד הוא מזיק לרבים וכופר בתורה ואף אם יאמין כמונו שהיא רבת התועלת כי הוא מחטיא הכונה והופך קערה על פיה . . . ועל זה אמרו ז”ל: “האומר” כי אף אם יפרש ויתקן דבורו באיזה צד מן התקון ‘והפירוש, לא יועיל לו שלא יקרא כופר. כי הוא מביא אחרים להחליש תקותם בתורה, ומחטיא כונת השם ית

This is a very original approach that some might wish to use to explain the Rambam as well. According to R. Nissim, what is important is the public declaration as this has the result of leading others to heresy. In fact, even if you really don’t believe what you are saying, since you are publicly stating a heretical position this is enough for you to be regarded as a heretic.

I have now responded to every comment of Grossman in the first half of his review, where he discusses broad themes. The second half of the review, which we turn to next, discusses specific points about the Principles. For those who have asked why I am taking the trouble to respond to every single point of Grossman, the answer is that it gives me a chance to revisit texts that I spent so much time on years ago. Secondly, it gives me the opportunity to share much new material that I think will be of interest to readers.

Before ending I would like to add a few more points. Earlier I mentioned that R. Hayyim knew the Guide of the Perplexed well. Some might be wondering what the basis for this statement is, because unlike the Rogochover, R. Hayyim does not discuss the Guide in his works. I am relying on R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik who testified that R. Hayyim wanted to write a commentary on the Guide (as well as on the Minhat Hinnukh), but he never had the time.[13] Here is how he is quoted in R. Zvi Yosef Reichman, Reshimot Shiurim: Sukkah, p. 258:

ואמנם כלל גדול אצלנו שאין להקשות על סתירה שבין ספר היד לספר מורה הנבוכים, כי כן קבל רבינו שליט”א מפי זקנו מו”ר הגר”ח זצוק”ל, וזקנו זצ”ל קבע כך כמופלג גדול בספר מורה נבוכים שרצה לכתוב עליו פירוש. גם חשב לכתוב הערות על הספר מנחת חינוך. ברם שתי המחשבות לא יצאו לפועל מפני טרדות בזמן; וחבל

R. Hayyim’s knowledge of the Guide is noteworthy since, as R. Aharon Rakeffet has commented many times, R. Moshe Soloveichik “never held the book in his hands.” While this might be an exaggeration, the underlying point is that R. Moshe had no interest in, or knowledge of, the Guide. I can’t say whether there is any influence of the Guide on R. Hayyim’s commentary on the Mishneh Torah. R. Eliyahu Soloveitchik actually cites the Guide as standing in opposition to R. Hayyim’s famous explanation of the two types of kavanah, found in Hiddushei Rabbenu Hayyim Halevi, Hilkhot Tefillah 4:1.[14]

Another noteworthy difference between R. Hayyim and the Guide is the following: The Rambam in Guide 2:45 explains that the books of the Prophets were produced from a higher level of divine inspiration than the books of the Hagiographa. However, R. Hayyim held that the difference between the Prophets and the Hagiographa is that the divine inspiration in the Prophets was originally intended to be spoken, and only later was written down. On the other hand, the divinely inspired books of the Hagiographa were originally intended to be written down. Thus, the difference between the Prophets and the Hagiographa has nothing to do with levels of prophetic inspiration.

This view of R. Hayyim is recorded in a number of different places, including by his son, R. Velvel.[15] R. Hershel Schachter also quotes this opinion from the Rav, who was passing on what his father, R. Moses, reported. Here is the passage in R. Schachter’s Nefesh ha-Rav, p. 240.

This entire passage is copied, word for word, in R. Gershon Eisenberger’s Otzar ha-Yediot Asifat Gershon, p. 411. But following a “tradition” that has now become somewhat popular in certain circles, Nefesh ha-Rav is not mentioned by name. Instead it is referred to as ספר אחד [16]

Returning to the passage from R. Soloveitchik quoted by R. Reichman, it is also of interest that R. Hayyim is quoted as saying that there is no point in calling attention to contradictions between the Mishneh Torah and the Guide. No reason is given for this, but no doubt it is because the works had different purposes, and this can explain different, even contradictory, formulations.

Regarding the Hazon Ish, in my book I assumed that he, and a number of other scholars who explained Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7 similar to him (including R. Ahron Soloveichik, Parah Mateh Aharon, Sefer Mada, p. 194[17]), never saw what Maimonides wrote in Guide 1:36 where he explains why an honest error in matters relating to principles of faith does not change one’s fate. As mentioned already, R. Kafih states that these words were written in response to Rabad’s criticism in Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7, where he states: “Why has he [Maimonides] called such a person a heretic? There are many people greater than and superior to him who adhere to such a belief on the basis of what they have seen in verses of Scripture and even more in the words of those aggadot which corrupt right opinion about religious matters.”[18]

I now believe that while it is certainly likely that some of the others I mention in my book had not seen the Guide, I would not say this about the Hazon Ish. Benjamin Brown has reasonably claimed that formulations in the Hazon Ish’s writings show that he was influenced by the Guide.[19] R. Yehoshua Enbal has harshly criticized Brown’s assertion that there was significant influence of the Guide on the Hazon Ish, but Enbal does not deny that the Hazon Ish knew the Guide.[20] It is reported that th Hazon Ish cited R. Moses Alashkar that Maimonides expressed regret about having “published” the Guide, and that if the work hadn’t already been spread so far, he would have removed it from circulation.[21] (This statement is not found in R. Alashkar’s works.) It seems to me that only one who had at least some idea of Maimonides’ philosophy, and why it could be viewed as problematic, would feel it necessary to identify with such an idea.

Can we point to any specific examples of influence of the Guide on the Hazon Ish? This is something that needs to be investigated and I am not prepared to offer an opinion on the matter. I would just note that R. Moshe Zuriel claims that a passage in the Hazon Ish about Divine Providence has its origin in Maimonides words in the Guide.[22]

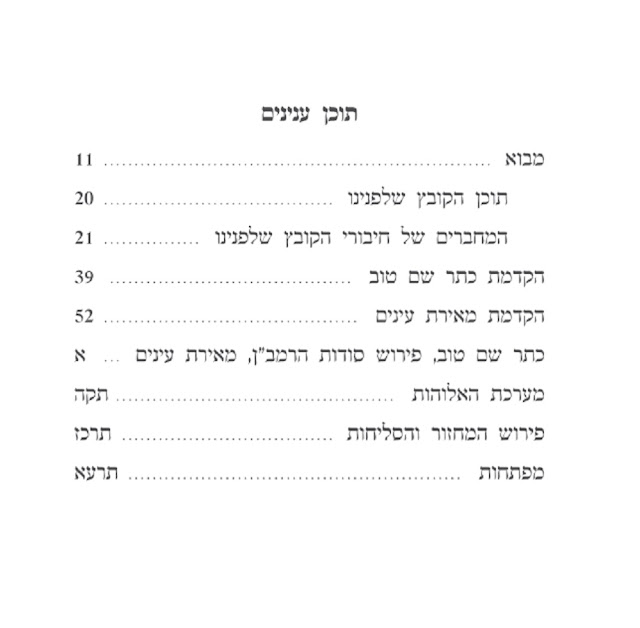

2. Earlier in the post I discuss the Hazon Ish’s letter,Kovetz Iggerot1:15, which may be the most famous of all of the Hazon Ish’s letters. I also provide an image from the actual handwritten letter. For this I thank Mrs. Hassia Yehuda who graciously allowed me to take pictures of this and the other letters I will discuss.

Mrs. Yehuda is the widow of Rabbi Dr. Zvi Yehuda (1926-2014). Yehuda was a very close student of the Hazon Ish from 1941 until the early 1950s. During some periods he learned with him almost every day for 2-3 hours, and the Hazon Ish became a father-like figure to him. The letter in Kovetz Iggerot 1:15 was sent to Yehuda, and this is what Yehuda himself wrote about this letter (published here for the first time).

As with another close student of the Hazon Ish, Chaim Grade, Yehuda chose a different path than what his teacher would have preferred: He enlisted in the IDF, attended university, and became part of the Religious Zionist world.

Here is a picture that you can find on the internet.

From the Hebrew Wikipedia page for the Hazon Ish we learn the picture was taken in Ramat ha-Sharon when the Hazon Ish was visting a yeshiva ketanah there and testing the students. The man to the right of the Hazon Ish is R. Elijah Dessler. The young man to the right of R. Dessler is Yehuda. The man on the far left is R. Shmuel Rozovsky. Here is another picture from the same event where you can see R. Rozovsky clearly.

Here is a picture of Yehuda from much later in life.

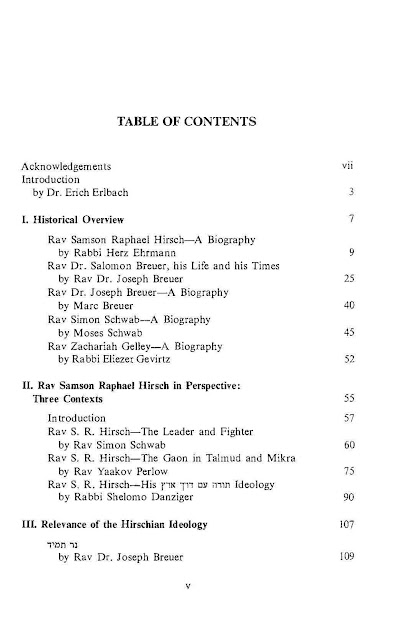

The letters of the Hazon Ish to Yehuda are important as they present us with his responses to a curious young man who started to question things. We are not dealing with someone like Chaim Grade who would throw out traditional Judaism entirely. Rather, Yehuda was beginning to open himself to a more liberal type of Orthodoxy, one which valued academic studies and engaging with the outside world. Yehuda later taught Mishnah on Israel Radio and collaborated with Pinhas Kehati in writing the famous Mishnah booklets. In these booklets Yehuda’s role was acknowledged, but when the booklets were later incorporated into Kehati’s published volumes unfortunately there was no longer any acknowledgment. After coming to the United States, Yehuda completed his doctorate at Yeshiva University and his dissertation is titled “The Two Mekhiltot on the Hebrew Slave”.[23]

In Brown’s book on the Hazon Ish, he quotes from a lengthy interview with Yehuda which was included as an appendix to Brown’s doctoral dissertation. With the approval of Brown, I have uploaded Yehuda’s very interesting interview here. You can also listen to Yehuda being interviewed about the Hazon Ish at Torah in Motion here. Yehuda also published two articles about the Hazon Ish in Tradition.[24]

Because the published version of the Hazon Ish’s letters does not reveal who they were sent to, people have no idea that Yehuda was the recipient of a number of important letters that are often cited. The earliest of the letters from the Hazon Ish to Yehuda is 1:41. According to Yehuda (in unpublished comments on the Hazon Ish’s letters to him), this letter is from 1944. Here we get a glimpse of the strong connection between the Hazon Ish and Yehuda, as the Hazon Ish ends the letter with הדו”ש הדבוק באהבתך. The content of the letter is also of interest as the Hazon Ish writes:

רב שלומים, מאד הנני מתענין לדעת משלומך, וחידה סתומה היא בעיני, שלא התראית עמדי טרם עזבך עירנו, ומה קרה אשר הכאיב לבבך הטוב, אשר מנעך משפיכת רוחך? ואשר מהרת לברוח. לא אוכל להאמין שתעזוב את התורה, כי נפשך קשורה בה בחביון נשמתך ואצילות נפשך העדינה, נא אל תכחד ממני דבר, והודיעני הכל

The Hazon Ish had apparently heard that Yehuda was going to abandon full-time Torah study. He was disappointed with this information and asked Yehuda to explain what was going on.

Yehuda replied to the Hazon Ish and this led to the Hazon Ish’s next letter to Yehuda, which is found in Kovetz Iggerot 1:42. In this letter the Hazon Ish offers guidance to Yehuda, designed to keep him on what today we would call the haredi path:

הריני מאחל לך שתהא דעתך נוחה מחכמתך בתורה, ואל יוסף כח מנגד להדריך מנוחתך, ולנדנד איתן מושבך, שים בסלע קנך, ושמה בסתר המדרגה, הוי שקוד ללמוד תורה, וראה חיים שתחת השמש אין לו יתרון אך למעלה מן השמש יש לו יתרון

Kovetz Iggerot 1:19 was also sent to Yehuda, and it was written after the letters already mentioned. In this letter the Hazon Ish deals with Yehuda’s choice to leave the yeshiva world:

באמת לא מצאתי את המסקנא כדרך הנכונה, אך בידעי שאי אפשר לאכף עליך לעשות נגד רצונך הטבעי . . . לא הרהבתי בנפשי להרבות דברים בשבח הישיבה . . . ואולי תבוא שעה מוצלחת ועבר עליך רוח ממרום בבחינת יעבור עלי מה! ותכיר ישיבתך בישיבה להיותר מתאימה לנפשך ולמשאה בחזות הכל

Kovetz Iggerot 1:14 is the last of the fourteen letters the Hazon Ish sent to Yehuda. This was written when Yehuda’s life choice had been made and the Hazon Ish recognized that his pleas to Yehuda to remain in the yeshiva world had gone unanswered. We see in this letter the Hazon Ish’s great love for Yehuda together with his great disappointment that his dear student had chosen a different path for his life. I don’t think there is another published letter from the Hazon Ish where he writes with such emotion. It is a tribute to Yehuda’s memory that the world can see how the Hazon Ish loved him, and I am happy to be able to reveal who the addressee of this letter is, as over the years many people have wondered about this, and sections of this letter have often been reprinted.

Here is some of what the Hazon Ish wrote to Yehuda:

רב הרגלי לערוך את החיים בודאות גמורה של י”ג העיקרים שעם ישראל עליהם נטעו הקנו לי אהבת התורה בלי מצרים. עשיר אני גם באהבת זולתי, וביחוד לצעיר מצוין בכשרונות, ולב מבין. צעיר השוקד על התורה מלבב אותי וצודד את נפשי, וזכרונו ממלא את כל עולמי, ונפשי קשורה בו בעבותות אהבה בל ינתקו

בראותי בך מפנה פתאומי, אשר כפי שתארתיו, מובנו לבכר החיים של השוק על החיים של התורה אשר בישרון מלך, נפגשתי במאורע רציני בלתי רגיל, והייתי צריך להבליג יום יום על גודל הכאב, ולא יכולתי להשתחרר מרב היגון, הבלתי נשכח כל היום. מצד אחד הייתי מתפלל על תשובתך ומצד השני היה מתגבר עלי היאוש, ובאהבת האדם את עצמו הייתי מסתפק אולי צריך להשתדל להשכיח את כל העבר, ולומר וי לי חסרון כיס, ומצד שלישי אהבתי אליך לא נתנני מנוחה. אבל אורך הזמן שעזבתני עזיבה גמורה ואין לך שום חפץ בי, הכריע הכף לפנות אל השכחה שתעמוד בי בעת צוקה, ומה כבד עלי שבאת לעורר אהבה ישנה, אשר תאלצני להאמין בתקוות משעשעות, אבל כח היאוש אינו רוצה להרפות ידו, ועוד נשאר בלבי, כמובן . . . [הנקודות במקור] אבל בערך אולי תבין מצבי. הכותב בכאב לב חפץ באשרו

The letters of the Hazon Ish to Yehuda have recently been donated to the National Library of Israel. See here.

3. In previous posts I discussed how letters from the Rabbi Isaac Unna archive formerly kept at Bar-Ilan University were being sold at auction. The final shoe has now dropped as what appears to be the remaining items in the archive are now up for auction. The lot is described as follows: “Large Archive Of C. 350 Documents And Letters To, And Accumulated By, RABBI ISAK UNNA Concerning The Campaign To Protect Kosher Slaughter (Shechitah) In Germany.” You can see it here. Thus ends this disgraceful saga in which the family donated numerous historically important documents to Bar-Ilan to be preserved in an archive for scholars to use, and instead these items ended up being sold to the highest bidder.

4. For a while I have been fascinated by the over-the-top language in various charity appeals. It is not enough to stress the importance of the cause, but people feel that they need to speak about how the giver will benefit as well. Furthermore, all sorts of phony stories about “yeshuos” are included in these appeals. However, I don’t recall ever seeing such a blatant falsehood as what appeared right before Purim here in an appeal from the Vaad Harabanim fund. This is the text of the appeal.

Group Of Frum Men Travelling To Dangerous Arab Territory

Thursday 25th of February 2021 07:01:23 AM

A hand-selected group of talmidei chachamim arrived in Iran from Israel this morning, sent on an important mission by Rav Chaim Kanievsky himself. Rav Kanievsky sent the emissaries to pray at the tombs of Mordechai & Esther on behalf of all those who donate to Vaad HaRabbanim’s matanos l’evyonim campaign.

The tomb has been preserved against all odds by Iranian Jews for centuries, despite attempts and even threats by the government to destroy it. The group of travellers runs considerable safety risk appearing externally Jewish and carrying Israeli passports through the hostile Arab country. They do it all for the sake of the hundreds of widows, orphans, and talmidei chachamim who are turning to Vaad HaRabbanim for help.

Funds collected will be distributed to poor people on the day of Purim, in keeping with the observance of the mitzvah of matanos l’evyonim.

Names are being accepted for the prayer list at the tomb for the next few days only.

Where to begin? First of all, Iran is not an Arab country. Second, Israeli passport holders are not allowed into Iran. Quite apart from this, think about the idiocy of this appeal. They expect the reader to believe that in the midst of Covid, with Ben Gurion Airport closed, a group of Israeli talmidei chachamim flew to Iran of all places. And we are also expected to believe that R. Chaim Kanievsky sent these talmidei chachamim to Iran. Anyone who did a little research would have also learned that the tomb was closed because of Covid and even Iranian Jews could not go there.

The story is so obviously phony that I wonder how anyone could so brazenly actually post it. And yet, as with all these ridiculous stories, some people appear to have fallen for it. On the page that you donate here it tells us that $7799 was raised for this idiotic appeal. On this page the appeal begins dramatically: “Right now, a plane full of talmidei chachamim is headed to Iran on a special mission from Rav Chaim Kanievsky himself.” It would have been bad enough had the appeal said that one or two people are going to Iran, but a “plane full”! Of course, if there was actually a group of talmidei chachamim traveling to Iran then the cost of this junket would be more than the $7799 raised, so the snake oil salesman who prepares the next phony appeal might consider the fact that people donating to charity would prefer that it actually go to the poor, not to fund a group of people going on a trip.

* * * * * * * *

[1] R. Elhanan Wasserman, Kovetz Ma’amarim (Jerusalem, 2006), p. 11. R. Shimshon Pinkus, Nefesh Shimshon: Be-Inyanei Emunah, p. 99, notes that there are those who have claimed that R. Hayyim’s statement is not to be taken literally, and that he too agrees that one who does not know any better is not to be regarded as a heretic. R. Pinkus responds as follows to this distortion of R. Hayyim’s view:

כפי שקיבלתי את הדברים מבית בריסק – הגר”ח התכוון כפשוטו ממש! יהודי החסר את ידיעת עיקרי האמונה – אף שלא באשמתו – אינו מחובר לאמונת ישראל. וכשאין דבר המחבר אותו לנצחיות הרוחנית, מציאותו מנותקת ואין לו חלק לעולם הבא.

[2] See his edition of the Guide of the Perplexed, 1:36, n. 37.

[3] R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik discusses the unwitting heretic in Shiurei Ha-Grid: Tefillin, ST”M Tzitzit, p. 84 and ibid., note 7:

בשחיטה, שדין פסול מומר מיוסד על ההשוואה לעכו”ם, אין אנו פוסלים את כל אלו שמומרותם לא בקעה ועלתה מתוך מעשה איסור מיוחד. ובנוגע לאיסורים מסוימים הגורמים למומרות, אנו יודעים כי רק שבת, עבודה זרה ואפיקורסות מחדשים פסול כזה. ברם בסת”ם, שלגביהם גם אפיקורס בשוגג פסול משום שאיננו מאמין, אף על פי שלא חטא, מכל מקום אין הפסול תלוי בחטא, כי אם במצב הגברא ובחלות שמו. מאמין בקדושת התורה כשר, ואילו אינו מאמין פסול . . . אמנם, באפיקורס בשוגג לא חל שם רשע כל כך, שהרי איננו כופר במזיד, ומכל מקום נקרא אפיקורס, ומהווה חלות מיוחדת בגברא, אף על פי שאינה מושרשת במעשה עברה זדוני

[4] See his letter in my Iggerot Malkhei Rabbanan, pp. 286-287.

[5] Teshuvot ve-Hanhagot, vol. 4, p. 452.

[6] Teshuvot ha-Rambam, ed. Blau, vol. 2, no. 264. R. Joseph Karo, Kesef Mishneh, Hilkhot Avodah Zarah 2:5 and Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:14, did not have Maimonides’ responsum and thus offered a different suggestion.

[7] She’elot u-Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, Even ha-Ezer, no. 148.

[8] The proper transliteration is kofer ba-ikar (or ikkar) as there is a kamatz under the ב not a sheva.

[9] In his commentary to Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7, R. Kafih writes:

כל “האומר” שהזכיר רבנו בהלכות הללו אינה סתם אמירה ודבור, אלא מי שהוא בדעה וסברא שכך הוא הדבר

[10] Le-Dofkei Teshuvah, p. 168.

[11] Emunah Shelemah, p. 158. Others who deal with the issue include R. Yitzhak Hecht, Sha’arei Kodesh, vol. 3, pp. 212-213, and R. Mordechai Movshovitz, Shalmei Mordechai, vol. 1, p. 4. R. Movshovitz writes:

וצריך לומר דלאו בדווקא נקט אומר אז חשוב מין, אלא כל שאומר רק במחשבה, הרי הוא עובר דהרי הוא כופר בעיקר

[12] Ma’aseh Nissim, ed Kreisel (Jerusalem, 2000), p. 160.

[13] See also R. Shimon Herschler, Gishmei Berakhah p. 495 (included in Herschler, Seh la-Bayit: Hiddushim u-Derushim al ha-Moadim [London, n.d.], who quotes Zalman Levine, the son of R. Hayyim Avraham Dov Ber Levine, the famous Malach, that his father studied the Guide of the Perplexed with R. Hayyim. Despite his father’s extremism, Zalman attended RIETS and shaved his beard. See Chaim Dalfin, Chabad and Gedolim II (Brooklyn, 2021), p. 155 n. 61. Although it is generally assumed that the title “Malach” was given to the elder R. Levine because of his piety, Dalfin quotes a report that the term was coined “to humiliate those individuals who joined Rabbi Haim Dovber Levine. The sentiment was that they put themselves on a pedestal making themselves ‘holier than thou'”. Habad Portraits (Brooklyn, 2015), vol. 3, p. 54 n. 89.

[14] “Ha-Tefillah be-Aspaklaryat ha-Rambam,” Yeshurun 9 (2001), p. 658. See similarly R. Moshe Yitzhak Roberts in his edition of R. Moses Trani, Beit Elokim: Sha’ar ha-Tefilah (Lakewood, 2008), section Kiryat Moshe, p. 269.

[15] Hiddushei Rabbenu ha-Griz ha-Levi, Menahot 30a.

[16] In the past I have referred to this phenomenon, and another example was recently mentioned by R. Yaacov Sasson in the Seforim Blog here.

[17] On this page R. Soloveichik also points to what he sees as a contradiction between how the Rambam regards unwitting heretics in Hilkhot Teshuvah and his position in Hilkhot Mamrim regarding people brought up in Karaite society, a matter already discussed in this post. He writes

אבל לכאורה זה סותר מה שכתב הרמב”ם בפ”ג מהל’ ממרים ה”ג שהצדוקים והקראים שנתגדלו וחונכו ע”י הוריהם להיות כופרים בתורה שבעל פה יש להם דין של תינוקות שנשבו ויש להם חלק לעולם הבא

In the copy of Parah Mateh Aharon on Otzar haChochma the words I have underlined are also underlined, and the following comment has been added:

פרי המצאת המחבר, ובר”מ שם ליתא (!) ולפי”ז אזדא כל תמיהת הרהמ”ח

The unknown author correctly notes that in Hilkhot Mamrim the Rambam never says that people brought up in Karaite society, who are unwitting heretics, have a share in the World to Come.

[18] Translation in Isadore Twersky, Rabad of Posquières (Cambridge, MA, 1962), p. 282.

[19] Ha-Hazon Ish (Jerusalem, 2010), pp. 171-172.

[20] Yeshurun 29 (2013), p. 938.

[21] Pe’er ha-Dor, vol. 4, p. 150.

[22] Le-Sha’ah u-le-Dorot, vol. 1, p. 283.

[23] The word מכילתא means “a measure”, yet why should the halakhic midrash be given this title? Isaac Baer Levinsohn, Beit Yehudah (Vilna, 1858), vol. 2, p. 48, suggests that the work was actually called מגילתא, but in the popular pronunciation came to be called מכילתא as ג without a dagesh sounded a lot like כ without a dagesh. This pronunciation of ג without a dagesh can still be heard among Middle Eastern Jews. Levinsohn, ibid., who is discussing halakhic midrash, also points out that Wolf Heidenheim, in his machzor for Shavuot in Yetziv Pitgam, vocalizes the words ספרא וספרין as Safra ve-Safrin, instead of Sifra ve-Sifrin. The words are also vocalized this way in Shlomo Tal’s Rinat Yisrael machzor.

Yet as Levinsohn points out, this would mean “writer and writers” –סופר וסופרים. Heidenheim was, of course, a great scholar (and Tal was also quite learned), so it doesn’t make sense that this is simply a mistake. Does anyone know of a source that ספרא should be read as Safra and not Sifra?

[24] “Hazon Ish on the Future of the State of Israel,” Tradition 18 (Summer 1979), pp. 111-117, “Hazon Ish on Textual Criticism and Halakhah,” ibid. (Summer 1980), pp. 172-180.