Reuven Elitzur, Saul Lieberman, and Response to Criticism, part 2

Reuven Elitzur, Saul Lieberman, and Response to Criticism, part 2

Marc B. Shapiro

Since I mentioned R. Reuven Elitzur in my post here, let me note two other interesting items from his posthumously published book, Degel Mahaneh Reuven. On pp. 304-305 we learn that when Elitzur studied in Ponovezh, one of the students joined the Irgun. When some other students found out about this, they grabbed the Irgun student one night, covered his head with a blanket, and beat him terribly. The result of this was that the student not only left the yeshiva, but abandoned religion entirely. Only many years later, due to Elitzur’s influence, did he begin to again observe Shabbat.

We see that Elitzur was in the United States at the time of the great fire at the Jewish Theological Seminary library in April 1966. From the passage we see that he would eat his breakfast at JTS.[1] It could mean that he brought his own breakfast with him, or it could also mean that he ate the breakfast in the Seminary cafeteria. If the latter, it could mean that he only ate the cornflakes or that he even ate cooked items. It is interesting that a text with such ambiguity, and thus liable to create “problems,” appeared in a haredi work. I therefore assume that the grandchildren who put the book together did not understand the significance of where the fire had taken place, namely, that it is not an Orthodox institution.[2]

Regarding Orthodox rabbis visiting the Jewish Theological Seminary, in R. Aharon Rakeffet-Rothkoff’s memoir, he tells the following story about R. Moshe Bick:

Meeting such a figure [R. Bick] in the Seminary library made me feel awkward. Utilizing the rabbinic aphorism, I asked the good rabbi: “What is a kohein doing in a cemetery?” . . . With a kindly smile embracing his face, the Bronx spiritual leader immediately responded: “If the Seminary possesses rare and invaluable rabbinic texts, they must also be available to all Torah scholars. The Seminary cannot withhold these treasures from Klal Yisrael.”[3]

In R. Pinchas Lifshitz, Peninei Hen (Monsey, 2000), pp. 99-100, there is a 1929 letter from R. Shimon Shkop to Cyrus Adler, Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary. In this letter, R. Shkop mentions meeting Adler at his Seminary office, at which time he spoke to him about the difficult financial situation of his yeshiva, Sha’ar ha-Torah in Grodna.

Regarding the Seminary, Nochum Shmaryohu Zajac called my attention to this video. In his discussion with Dr. Dov Zlotnick, we see the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s positive attitude towards Saul Lieberman (which I already mentioned in Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox).[4] It appears, however, that the Rebbe was confusing Lieberman and Louis Finkelstein when he referred to Lieberman’s connection to Torat Kohanim, and that he wrote he’arot and mar’eh mekomot to it. Torat Kohanim, otherwise known as the Sifra, was in fact Finkelstein’s great project.[5]

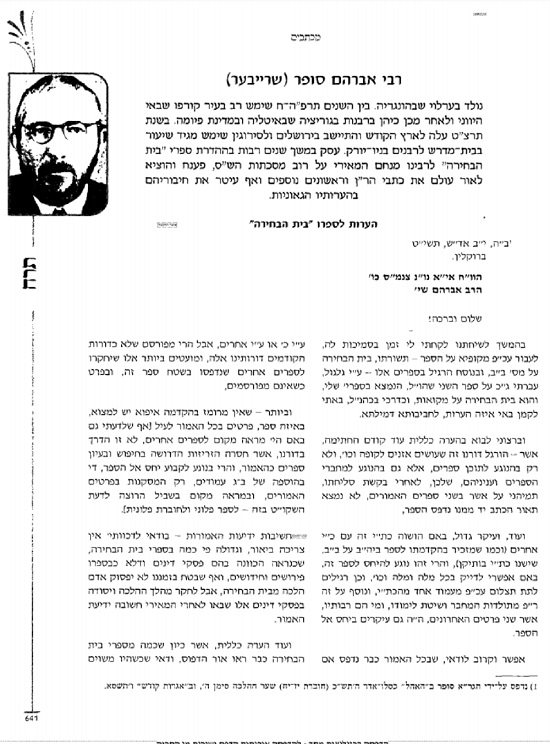

Another teacher at JTS was R. Abraham Sofer, who published the Meiri. A number of letters from the Lubavitcher Rebbe to him are included in Menahem Meshiv Nafshi (Jerusalem, 2012).

Here is vol. 2, p. 608.

I am quite surprised that R. Sofer is described as a “maggid shiur” at בית מדרש לרבנים. Is it possible that the editors did not realize that בית מדרש לרבנים is not an Orthodox institution?

Returning to Lieberman, in my post here I noted that Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish, vol. 2, published a lengthy letter from Lieberman to the Hazon Ish. Subsequent to that post, volume 3 of this series appeared, and beginning on page 319 we have two lengthy letters from the Hazon Ish responding to what Lieberman wrote. He begins with the following words which present a traditional perspective in opposition to the academic approach of Lieberman.

אם אמנם הבלשנות ותרגום המילים נוטל חלק בתורה שבע“פ לאחר שנתנה לכתוב, אבל הרצים אחריה מדה ואינה מדה, ואין התורה מצוי‘ בין אלה שעושים את מלאכתם קבע ואת עיון העמוק עראית או אינם מתעמלים בו כלל. ולאלה שעמלים בתורה אין פרי עבודתם של חוקרי הלשון מועיל רק לעיתים רחוקות, ובדברים קלי ערך, ומגמת המתעמל להתוכן ולא לתרגום המלה שהוא בבחינת תיק

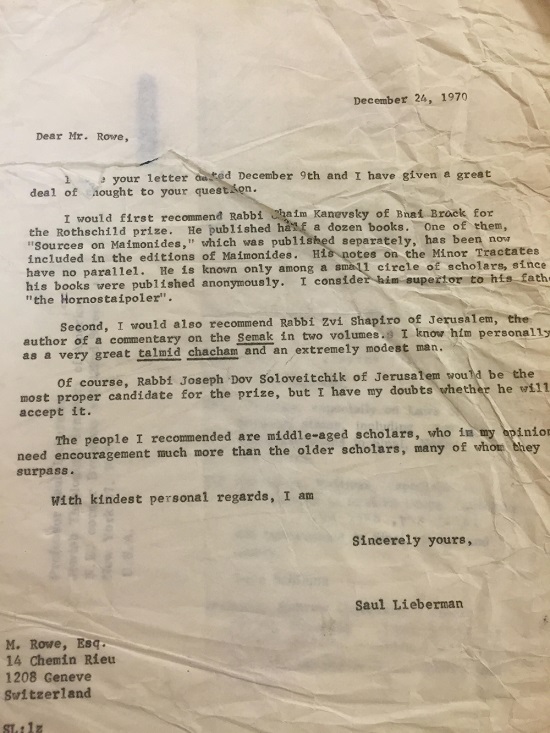

I think readers will also find interesting a letter in the Lieberman archives at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. I was alerted to this by Ariel Fuss.[6] Max Rowe represented the Rothschild Trust which awarded four monetary gifts to outstanding rabbinic scholars. Rowe turned to Lieberman for his recommendations on who should receive the awards. Although today everyone knows about the greatness of R. Hayyim Kanievsky, we see that Lieberman was aware of this fifty years ago, and recommended him for the grant. He even regarded R. Hayyim as greater than his father, the Steipler. Of all the significant figures Lieberman could have suggested, it is fascinating to see whom he chose.

I still have a good deal to write about Lieberman, as I have collected a lot of new material since the publication of Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox. For now, here is a picture of a young Lieberman and his wife, Judith, that has never before appeared in print or online. I thank Professor Meir Bar-Ilan for sending it to me.

* * * * * *

Continued from here. Let us resume with Grossman’s review, going page by page. First, I must thank everyone who wrote to me offering support. Many of these people are in the haredi world and have been reading my material for years, and others have listened to my Torah in Motion classes. They all knew that I had never mocked rishonim and aharonim,[7] an accusation I referred to as “slander”.[8] A number of people asked me how to explain why Grossman so mischaracterized my book, as it certainly wasn’t intentional. My response to them was that if you come to a task with a preconceived negative view, on a mission of destruction, then you will not be able to judge a book fairly. You won’t even realize how you are not being fair, and this in turn will lead to all sorts of mistakes. In the introduction to the Guide of the Perplexed, the Rambam addresses readers of his book:

If anything in it [the Guide], according to his way of thinking appears to be in some way harmful, he should interpret it, even if in a far-fetched way, in order to pass a favorable judgment. For as we are enjoined to act in this way toward our vulgar ones, all the more should this be so with respect to our erudite ones and the sages of our Law who are trying to help us to the truth as they apprehend it.

What the Rambam is saying is that readers should give authors the benefit of the doubt, and only if an author is clearly incorrect should one then feel comfortable expressing criticism. He says that we should act this way even “toward our vulgar ones,” the category that I and so many others would best be placed in, rather than in the category of the “erudite” and “sages of our Law.”

Unfortunately, Grossman was not careful in the way he wrote. R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach already warned us about the problems that arise from this, with a nice witticism:[9]

ואפילו בכתבי הדיוט אומרים בעלי הלצה השמר פ“ן [פען הוא בלשון יהודי פולין שם לקולמס, פעדער, והוא מלשון רומית Penna. הערת המו“ל] כי א“א לפרש דבריו או להתנצל בהם ע“י חסר או יתור או חלוף מלה כמו שעשה יעשה באמרי פיו.

Another relevant witticism is mentioned by Samson Bloch [10], that the word מבקר (reviewer or critic) stands for מתכבד בקלון רעהו.

On pp. 38-39, Grossman quotes me as saying that the Rambam’s conception of Ikkarim was an innovation, and that this is not just something mentioned by academics but is also found in traditional writings. There is nothing controversial in this statement, and as many readers know, Rambam was criticized for having too many Principles (R. Joseph Albo) or for having too few (R. Isaac Abarbanel).

Grossman writes (p. 39):

Shapiro writes this despite the fact that an array of classic scholars, among them Alshich, R. Moshe Chagiz, Beney Yisoschar and Mabit believe otherwise. The latter, in a section of his Beys Elokim devoted to the Principles, begins his discussion with this comment. “All the main Principles of the Torah and its beliefs are either explicit or hinted at in Torah, Prophets, the Hagiographa, and in the words of Chazal received from a tradition; in particular, the three Principles which include them all.”

All this is completely irrelevant to what I have said. The issue is not whether the Rambam’s Principles can find support in the Torah, Prophets, Hagiography, or Chazal. Of course Rambam can find support for his Principles in earlier sources. What I and everyone else (rishonim, aharonim, and academic scholars) are speaking about is something entirely different. It is whether the Rambam’s specific conception of Principles of Faith – that belief in the Principles, despite all other sins, are enough to ensure a share in the World to Come, and denial or doubt of a Principle, despite one’s piety and halakhic punctiliousness, will prevent one from having a share in the World to Come – is found in any other source before the Rambam. I also stated that no one before the Rambam had picked thirteen specific Principles as the basis of Judaism. As far as I know, every single rishon who wrote about the Principles agrees with this point. Unfortunately, Grossman once again completely misunderstands what I have stated.

Grossman writes (pp. 39-40):

Nothing shows more clearly that the Rambam based his Principles upon the Talmud than the fact that in Hilchos Teshuvah [3:6-8], he lists the various heretics under three classifications: min, apikores and kofer baTorah, all of whom lose their share in the World to Come. Obviously, each group violates a particular fundamental of faith, or else why would they be listed separately? Shapiro explains this by saying: “For his own conceptual reasons which have no talmudic basis, Maimonides distinguishes between the epikorus, the min and the kofer batorah.” [Limits of Orthodox Theology, p. 8 n. 27] But these terms are not, as Shapiro would have them, the Rambam’s inventions. They are taken from an explicit passage of the Talmud in Rosh ha-Shanah 17a which lists these three classes of heretics as those who lose their portion in the World to Come. They are obviously not a product of Rambam’s ‘conceptual reasons.’”

Every reader should be able to see Grossman’s error. Contrary to what Grossman attributes to me, I did not say that the terms epikorus, min, and kofer ba-Torah are the Rambam’s inventions based on his “conceptual reasons.” (He must think I am really ignorant as he assumes that I do not know that the terms epikorus and min are found in the Talmud.) What I said was that the way the Rambam distinguishes between these categories is based on his own conceptual reasons. In other words, why do certain heresies fall into the category of epikorus, others into the category of min, and others into kofer ba-Torah. For some heresies, we can see that the Talmud refers to the holders of these views as minim, but for others, it is the Rambam who determined the divisions, and we cannot find a talmudic basis. There is also no consistency in the Rambam’s own writings for what is included in the category of min.[11]

R. Nachum Rabinovitch writes as follows in his Yad Peshutah to Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:8, in discussing how the Rambam determined who is placed in the category of epikorus (as opposed to say, kofer ba-Torah). What I have underlined is particularly important. Is Grossman now going to be attacking R. Rabinovitch?

כאן שרצה רבינו לחלק בין כופרים שונים לפי מושגים יסודיים, לפיכך השתמש במונח אפיקורוס לא כפי הוראתו הרחבה בדברי חז“ל שהשווהו למלה ארמית אשר שרשה פקר, אלא כפי מובנו בתולדות הפילוסופיה, דהיינו, מן הכת של הוגה הדעות היווני אפיקורוס . . . על כן הגביל את המונה אפיקורוס למי שכופר בהשגחה, זאת אומרת, מכחיש שד‘ יודע, וממילא כופר גם באפשרות שה‘ מודיע לבני אדם ובתוכם גם משה רבינו. נמצא שהמונח מין מיוחד לאמונות כוזבות על הבורא עצמו, ואפיקורס מיוחד לדעות נפסדות על יחס הבורא לאדם

I refer to R. Rabinovitch’s commentary in Limits, p. 9 n. 27, right after the passage cited by Grossman which he misunderstood and found so objectionable. Had he examined what R. Rabinovitch wrote, he might not have misunderstood what I was saying.

In this note I also refer to Menachem Kellner, Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought, pp. 20-21. On p. 21, Kellner writes: “Maimonides does not carefully distinguish among the terms sectarian, epikoros, and denier.”

I also refer to R. Yitzhak Shilat, who in his note in Iggerot ha-Rambam, vol. 1, pp. 38-39, after discussing the different ways the Rambam refers to heretics in his various works, writes as follows with reference to the term min:

ונראה שהסבר הדבר הוא, שבהלכות תשובה נכנס הרמב“ם לחלוקה תיאורטית של סוגי הכפירה השונים, ושם הוא מייחד את המונח “מין” לסוג מסוים של כפירה, דהיינו לכפירה באחד מעיקרי אמונת הא–להות, אך במובן יותר מעשי ורחב הוא משתמש במונח “מינות” לכל כפירה באחד מיסודי האמונה (ובהפניה מהל‘ שחיטה להל‘ תשובה התכוון לכל סוגי הכופרים המנויים שם)

.ואכן, הרחבת מושג ה“מינות” והחלתו על כל כפירה באחד מיסידי האמונה, מפורשת בדברי הרמב“ם במקומות אחדים . . . הרחבה נוספת של השימוש במונח “מין” אנו מוצאים בהמשך דברי הרמב“ם

נמצאנו למדים שהרמב“ם משתמש במונח “מינות” לא פחות מאשר בשלושה מובנים, זה רחב מזה: א. כפירה ביסודי האמונה השייכים למציאות ה‘. ב. כפירה באחד מכל יסודי האמונה. ג. כפירה בתורה שבעל פה

As the reader can see, R. Shilat explains how when it came to categorizing heresy, the Rambam used “his own conceptual reasons.”

In my note in Limits (p. 9 n. 27) I did not refer to R. Kafih’s commentary to Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7, but it is also important regarding this matter. After mentioning those who questioned why the Rambam included what he did in the category of epikorus, seeing that various talmudic passages define an epikorus differently, R. Kafih states that this matter is easily explained, namely, the Rambam is not using the term epikorus the way it is used in the Talmud. Rather, he is using the Greek term, and placing into this category those heresies that can be identified with Epicurean philosophy.

ולפיכך כל מה שמקשים על דברי רבנו כאן מאפיקורוסים שונים שנאמרו בש“ס, לק“מ, כי שם מדובר בהטית המלה העברית הפקר בלבושה הארמי אפקירותא, וכאן מדובר במלה שמקורה יוני ע“ש אפיקורוס

R. Kafih explains further in his commentary to Mishneh Torah, Sefer Nezikin, p. 594:

שכל שבוש תעיה וכפירה השייכים לא–להות נקרא מין. וכל תעייה שבוש וסטייה השייכים לנבואה נקרא אפיקורוס. ובנדפס טרפו וערבבום יחד

R. Judah Albotini does not even think that we should pay the distinctions the Rambam gives to the different types of heretics much mind, as the different terms are “lav davka”.[12]

ואפילו הרב ז“ל בעצמו משנה דבריו בהם כי פה כתב שהמינים הם אלו הה‘ שמות (ובס‘) [ובהלכות] רוצח שהמין הוא העובד ע“ז או האוכל נבלות להכעיס ובה‘ עירובין קרא לישראל העובד ע“ז שהוא כגוי ולא קראו מין וקרא מינים לצדוק ובייתוס וכל הכופרים בתורה שבעל פה ולאלו קרא בכאן כופרים הרי לך שכל אלה השמות לאו דוקא קאמר אלא ע“ד העברה

The most detailed discussion of how the Rambam categorizes the various types of heretics is found in Hannah Kasher, Al ha-Minim, Ha-Apikorsim, ve-ha-Kofrim be-Mishnat ha-Rambam. This book appeared in 2011, too late to be mentioned in Limits. On p. 15 she writes (emphasis added):

הרמב“ם לעתים הציע הגדרה מכוננת למונחים, וקבע כיצד לטעמו יש להשתמש בהם מעתה ואילך. . . הרמב“ם המיר לעתים באופן רדיקלי את משמעותו של המונח המסורתי ויצק לתוכו תוכן שונה.

On pp. 40-42, Grossman deals with my suggestion that the Rambam abandoned his Thirteen Principles of Faith as the summation of Jewish dogma in favor of his more detailed formulation in the Mishneh Torah. In support of this suggestion I point out that not only does the Rambam pretty much ignore the Thirteen Principles in his later works, but in discussing what to teach a convert, he also does not mention the Thirteen Principles. (Regarding converts, he only states that they should be instructed in the oneness of God and the prohibition of idolatry.) I also note that both R. Joseph Schwartz and R. Shlomo Goren argued that in his later years the Rambam no longer felt tied to his early formulation of the Thirteen Principles. Readers should examine Limits for more details. My thoughts in this matter were in the way of a suggestion, not an absolute conclusion, that I thought worthy of bringing to the attention of readers.

In response to my point that when evaluating the significance of the Thirteen Principles for the Rambam it is noteworthy that he does not require a future convert to be taught these Principles, Grossman states that the Rambam derived his ruling, that the convert is instructed in the oneness of God and prohibition of idolatry (but not other Principles), from the talmudic recounting (Yevamot 47b) of the dialogue between Naomi and Ruth: Naomi says that Jews are prohibited to serve idolatry, and Ruth replies “Your God is my God.”

The Rambam understands this discussion as referring to the Principles of idolatry and God’s unity. Apparently, adopting these two Principles is the essence of conversion to Judaism. These might be a mere sample of other laws and ideas that we also mention—as implied by the Rambam’s concluding phrase [Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2], “and we elaborate (u-ma’arichin) on this.” The Rambam is codifying that which the Talmud prescribes as integral to the conversion process, thus, one cannot ask why the Rambam did not mention other Principles of faith—which is a different topic entirely.

This is a perfect example of how Grossman’s review could have been written, namely, present my points and then explain why he reads the texts differently and why my reading is forced, inconsistent with what the Rambam says elsewhere or with the Rambam’s sources, or just flat out wrong because I misread a text. In this case, I would only note that I still believe that my point about the Rambam not returning to the Thirteen Principles in his later works, even when he discusses the fundamentals of faith, is more than a little curious and leads to my original suggestion that at the time he wrote the Mishneh Torah he had adopted a more detailed list of required beliefs.

As for the matter of conversion, what about the Third Principle? For the Rambam, belief in divine corporeality is a denial of God’s existence, since a corporeal god is not God. Therefore, according to the Rambam, this is something that everyone, from childhood, needs to be instructed in.[13] Belief in divine corporeality usually turns into a form of idolatry, since one who worships a corporeal god is worshipping something other than God.[14] Thus, it is obvious that according to the Rambam instruction about God’s incorporeality would be part of the instruction about the unity of God. However, Principles 4-13 are not included in a convert’s instruction, even though in his Commentary to the Mishnah, when he lists the Thirteen Principles, the Rambam states that all the Principles are obligatory beliefs. It is these missing Principles of faith that I have wondered about, and asked why the Rambam did not require a convert to be instructed in them. Grossman’s explanation for this is that since the only theological matters the Talmud requires instructing a convert in are God’s unity and the prohibition of idolatry, the Rambam would not add to this on his own.

Grossman continues by stating that I am operating under

a misconception of the structure of the Rambam’s work. The Rambam himself states explicitly in his letters—and so it is axiomatic to Torah scholars—that he never made a statement in his Mishneh Torah which did not have a source in the Talmud. Whenever he records his personal opinion, he prefaces it with the words, yeyra’eh li—“it would appear to me.” Anything in his Mishneh Torah that seems different from the Talmud is due to the Rambam’s unique interpretation of the particular passage of Talmud. Thus, the question, “If the Rambam added to the Talmudic prescription, why did he not add the other Principles?” is not applicable. . . . The Rambam is codifying that which the Talmud prescribes as integral to the conversion process, thus, one cannot ask why the Rambam did not mention other Principles of faith—which is a different subject entirely. (pp. 41-42)

Before getting to Grossman’s major criticism, let’s clear up some inaccuracies. The Rambam does not say in his letter to R. Pinhas ha-Dayan, referred to by Grossman (Iggerot ha-Rambam, ed. Shilat, vol. 2, p. 443), that everything in the Mishneh Torah comes from the Talmud. He mentions the Talmud, but he also mentions halakhic Midrash and Tosefta. He then says that if something comes from the Geonim, he indicates so. Furthermore, and this is a very important point, the Rambam is speaking about halakhic matters, that for these there is always a prior rabbinic source.[15]

To say, as Grossman does without further clarification, that the Rambam “never made a statement in his Mishneh Torah” that has no talmudic source is simply incorrect. There are a number of statements in the Mishneh Torah dealing with science and philosophy for which there are no talmudic sources, a point that has been noted by the traditional commentaries. At the end of Hilkhot Kiddush ha-Hodesh, ch. 17, the Rambam tells us that the astronomical information he provides comes from Greek texts, as the Jewish writings on these matters were lost. Many who have studied this section of the Mishneh Torah have wondered if this is to be regarded as Torah study? R. Hayyim Kanievsky cites the Hazon Ish who is quoted as saying that despite the Greek origin of this information, once the Rambam included it in his book it became Torah.[16]

ואמרו בשם מרן החזו“א זצ“ל שאע“פ שהרמב“ם העתיק החשבונות שבפרקים האחרונים של קה“ח מהגוים כמש“כ בספי“ז מ“מ אחר שהרמב“ם כתבם נעשה תורה ממש והלומדם לומד תורה

R. Jacob Kamenetsky states[17] that most of what appears in the first four chapters of Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah, which the Rambam viewed as basic to Judaism, is not to be regarded as Torah but as פילוסופיא בעלמא.

ובעל כרחנו אנו צריכין לומר שמה שמסר לנו הרמב“ם בפרקים אלו אין זה לא מעשה מרכבה ולא מעשה בראשית, אלא כתב כל הד‘ פרקים אלה מדעתו הרחבה מתוך ידיעות בחכמות חיצוניות, כלומר שלא מחכמת התורה, אלא הרי זה פילוסופיא בעלמא – ונאמר שכבר השיג עליו הגר“א ביו“ד סי‘ קע”ט סקי“ג שהפילוסופיא הטתו ברוב לקחה ועיי“ש, והרמב“ם כתב פרקים אלו רק בתור הקדמה לספר יד החזקה, ועיקר הספר מתחיל מפרק ה‘: כל בית ישראל מצווין על קידוש השם וכו‘, ואין לדמות טעויות בהלכות אלו לטעיות בהלכות שבת וכדומה

R. Tzadok ha-Kohen even states that some of the historical information that the Rambam provides at the beginning of the Mishneh Torah is not based on earlier rabbinic sources, but is the Rambam’s own suppositions.[18]

וראיתי להרמב”ם בהקדמת ספר היד מנה סדר הקבלה ממרע”ה עד עזרא כ”ב דורות . . . ואם קבלה נקבל אבל כמדומני כי מסברא והשערת הלב לבד הוא שאמר זה שהרי בהקדמתו לפירוש המשניות כתב רק עד ירמי’ . . . הנה לא הי’ נודע לו עדיין סדר מבואר רק שבעת שחיבר ספר היד המציא מנפשו לכוין סדר מ’ דור מימות משרע”ה עד רב אשי והמציא סדר קבלה מנפשו וכתבו סתם כאלו קבלה היא בידו, אבל באמת יש להשיב ולטעון הרבה על דבריו

Let us now return to Grossman’s main point, which is to discount my question as to why the Rambam does not mention the Thirteen Principles when it comes to converts. He states that there is no talmudic source requiring this, and that if I understood what the Mishneh Torah is about I never would have had this question.[19]

The problem with the way Grossman writes about this is that although he wants people to see that my question shows that I am an amateur, in so doing he ends up disrespecting many great Torah scholars. When I wrote my book, I did not know of anyone else who raised this question, so it looks like it is original to me (and Grossman can therefore use it as part of his attack). However, subsequent to the book’s publication, I have found a number of others who wonder the same thing I did. While I might not understand how the Mishneh Torah works, is Grossman comfortable saying the same thing about the Torah scholars I shall now mention?

R. Hayyim Sofer writes as follows, with reference to the issue of conversion:[20]

והדבר נפלא הלא יש י”ג עיקרי הדת והי’ לו לב”ד להאריך בכל השרשים

R. Yaakov Nissan Rosenthal, author of the multi-volume commentary on the Mishneh Torah, Mishnat Yaakov, writes as follows in his comment on Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2.

צ“ע למה כתב הרמב“ם עיקרי הדת שהוא ייחוד השם ואיסור עכו“ם, ולמה לא כתב כל הי“ג עיקרים שכתבן בפירוש במשניות בפ“י דסנהדרין, וז“ל: שעיקרי דתנו ויסודותיה שלשה עשר יסודות, וראה שם בהמשך הדברים, ולמה כתב כאן: עיקרי הדת שהוא ייחוד השם ואיסור עכו“ם, וצע“ג

R. Rosenthal sees it as a real difficulty that the Principles are not mentioned. I am sure he would not be bothered, as I am not, by what the Rambam writes in his letter to R. Pinhas ha-Dayan, for we are not dealing here with a technical halakhic matter, but with the basis of Jewish faith, and it is not at all an ignorant question to wonder why the Rambam did not include the Principles. On the very first page of his commentary to Sefer ha-Madda, R. Rosenthal also notes the point I made, that the Thirteen Principles as a unit are never mentioned in the Mishneh Torah, something that surely cries out for explanation.

ותימא למה לא הביא הרמב“ם בספרו ה“יד החזקה” את הענין הזה של י“ג עיקרי האמונה, וצ“ע

R. Hayyim Amsalem also feels the need to explain why the Rambam does not require instructing converts in the Thirteen Principles:[21]

ולכן לא הצריך גם הרמב“ם י“ג עיקרים כולם שאם מודיעים לו איסור ע“ז ויחוד השם די בהודעה הזו עם מה שבא להסתפח בנחלת ה‘ ובשם ישראל יכנה, ואין מקום לפשפש יותר מדי בעניינים האלו כמו ענייני האמונה אשר מי יאמר זכיתי לבבי

R. Iddo Pachter writes:[22]

בהלכות איסורי ביאה יד, ב, כשהרמב“ם מציב את העיקרים כראש וכעיקר הנושאים המלמדים את הגר, הוא אומר: “ומודיעין אותו עיקרי הדת, שהוא ייחוד השם ואיסורי עכו“ם. ומאריכין בדבר הזה.” ואילו את העיקרים אחרים של התורה והגמול אין הרמב“ם מזכיר כלל. ונשאלת השאלה: למה השמיט במקום מרכזי זה של כניסה לכלל ישראל את שאר הדוגמות המהוות תנאי לכניסה

Grossman can still argue that all of these sources are misguided in even raising the issue of why converts are not instructed in the Thirteen Principles. Yet I think we should all agree that this is a matter that reasonable people can disagree about, and it should not be used an example to show the world that I am clueless about the Mishneh Torah. Grossman might not think it is a big deal, but many readers will agree with me that the fact that the Rambam would allow someone to convert without being taught all Thirteen Principles is quite noteworthy.

R. Yisrael Meir writes:[23]

הרי שבשעת גירות אי“צ לדעת כל הי“ג עיקרין, אבל אח“כ אם יכפור ה“ז אין לו חלק לעוה“ב.

Just as the convert does not know all the halakhot, and on the very first Shabbat might make mistakes, so too, according to the Rambam’s instructions about conversion, he will not know all the Principles of Faith. There are endless halakhot and it is not feasible to have a convert become an expert in every area of halakhah. Yet the Principles of Faith are not that many, and contrary to Grossman, I reject the notion that the Rambam would have needed an explicit talmudic text to require this, as he viewed it as basic to Judaism.[24]

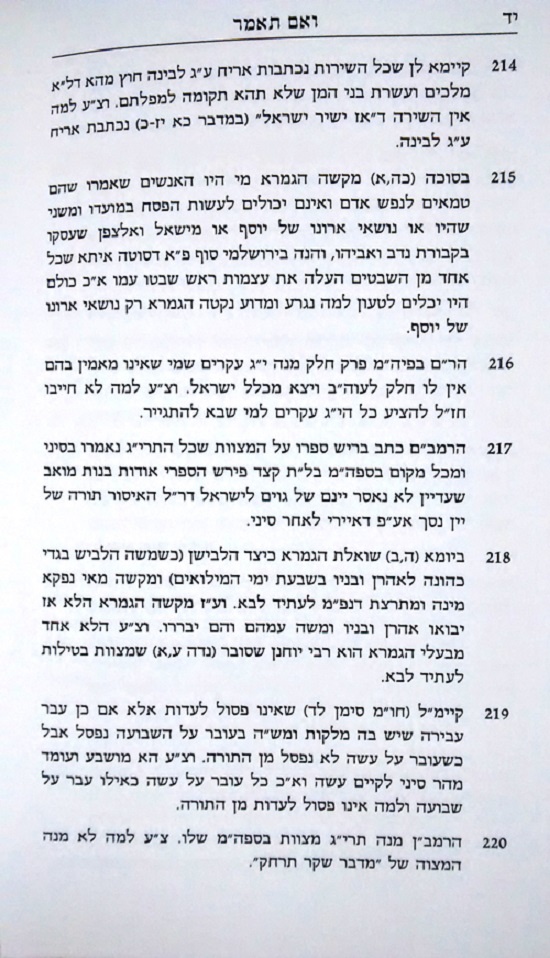

Relevant to what we have been discussing, R. Dovid Cohen writes as follows in the seventh volume of his book of questions, Ve-Im Tomar, p. 14, no. 216.[25]

When the questions are not his own, R. Cohen is always careful to record his source. This is a very admirable trait that we should all take to heart. Here is p. 77 no. 216, where he provides the source of the question.

While I am honored to be mentioned, I think that R. Cohen wrote this from memory. I say this since in the book I ask why the Rambam does not mention anything about teaching a prospective convert the Thirteen Principles. I don’t ask this question about talmudic sages.[26]

Before concluding this section of my reply, I want to return to a point I made in the book (p. 7), that the Rambam’s formulation that a convert be instructed in theological matters is something the Rambam added on his own without a specific talmudic source. Grossman rejects this and notes that the Vilna Gaon and others see the Rambam’s source as Yevamot 47b, where Naomi is recorded as telling Ruth that Jews are prohibited in idolatry, and Ruth responded that “your God is my God”.

The first thing I would say is that I am not certain if in this case the Vilna Gaon sees this as the source for the Rambam, or if he is simply citing a source that can be brought in support of what the Rambam, followed by the Shulhan Arukh, write. Chaim Tchernowitz writes about the Gaon’s commentary:[27]

לפעמים הוא מוצא לדין השו“ע סמך או רמז בכתוב עצמו, דבר שלא עלה על דעת שום איש ואף לא על דעת אותו המחבר בעצמו, אחד מן האחרונים, שהמציא את הדין או המנהג ההוא על דעת עצמו, על סמך דיוק בגמרא או באיזה ראשון שהמציא בפלפולו, והגר“א מראה לדין זה מקור מן התורה, מן הנביאים או מן הכתובים או מתרגומים עתיקים על פי רמז דק מן הדק

Let me illustrate this question by one example. If you look at Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 1:1, R. Moses Isserles is citing the Guide of the Perplexed. The Vilna Gaon, who knew the Guide and thus knew the basis of R. Isserles’ formulation, still cites talmudic passages as the source for R. Isserles, or perhaps we should say, as the the source for the Rambam. Does this mean that the Gaon is telling us that the Rambam’s statement in the Guide is actually based on the talmudic passages the Gaon cites?

Nevertheless, even if the Gaon is not citing Yevamot 47b as the actual source of the Rambam’s requirement for theological instruction for a convert (and I am not sure about this), there are indeed others who do cite this text, so Grossman’s point is well taken.

My response to this is that there are also authorities who do not identify Yevamot 47b as the Rambam’s source, and who instead see the Rambam’s mention of the necessity of instruction of converts in theological truths as something the Rambam added on his own, and not based on any talmudic text. Rather, they believe that the Rambam regarded the necessity of theological instruction as so basic and implicit that there does not need to be a specific talmudic text as a source. This is a dispute among the commentators, so it makes no sense to criticize me for advocating one side of this debate. Before citing some traditional authorities, let me first mention what my teacher, Professor Isadore Twersky, said about this matter. I realize that Grossman, who is not positively inclined to academic scholars, does not need to accept Twersky’s opinion any more than mine, but at least readers will see that nothing I have said is from left field, as it were.

In his Introduction to the Code of Maimonides, pp. 474-475 (and note 293), Twersky states that the notion that “every phrase and nuance of the MT is explicit in some source” is “misleading. It fails to acknowledge the interpretative-derivative aspects of the MT.”

Twersky also rejects the notion that the instructions in theology given to a convert are based on a particular talmudic passage (the very point on which Grossman criticized me):

Maimonides’ description of the procedure of conversion to Judaism vividly reflects his uniform insistence upon the indispensability of knowledge of the theoretical bases and theological premises of religion. A potential convert must be carefully informed about Judaism and instructed in its ritualistic patterns and, most emphatically, its metaphysics, its dogmatic principles—Maimonides emphasizes that the latter must be presented at great length. Now the need to expatiate concerning the theological foundations, in contradistinction to the ritual commandments, is not mentioned in the Talmud. Some scholars were inclined to assume that Maimonides found these details in his text of the tractate Gerim, inasmuch as a few other variants can be traced to this source, but this seems to be a gratuitous assumption. Given the Maimonidean stance, this emphasis is a logical corollary or even a self-evident component of the underlying text, which stipulates that the convert be informed about “some commandments.” . . . As a matter of fact, the entire presentation bristles with suggestive Maimonidean novelties which should not be glossed over and obscured.[28]

It is easy to say that I have a “misconception of the structure of the Rambam’s work.” Will Grossman say the same thing about Twersky?[29]

R. Baruch Rabinovich, Heishev Nevonim, ed. R. Nosson Dovid Rabinowich, pp. 13-14 (emphasis added), explicitly rejects Yevamot 47b as the Rambam’s source, and makes the exact same point I did about the Rambam not needing an explicit talmudic source for his statement that a convert is given theological instruction.

בביאור הגר“א (שם) מציין כמקור לדברי הרמב“ם אלו ליבמות (מז: ) לדרשת רבי אלעזר מאי קראה וכו‘ שאמרה נעמי לרות “אסיר לן ע“ז” ועל זה השיבה רות “ואלוקיך אלקי (רות פ“א פט“ז) – אבל אין הכרח לומר שמשם לומד הרמב“ם דין זה אלא שהרמב“ם מסברא דנפשי‘ פסק כך, כמושכל ראשון, שאין גרות ואין שייכות ליהדות, כל עוד אין אמונה בייחוד ה‘, והסתייגות מע“ז. וכן דעת הה“מ. בכל אופן מ“ש “ומאריכין עמו דבר הזה“, אין זה המקור [!] אלא מסברא דנפשי‘.

Grossman can reject R. Rabinovich’s statement, but he cannot say that R. Rabinovich did not understand “the structure of the Rambam’s work.”

A commentary on the Mishneh Torah that I often turn to is R. Asher Feuchtwanger’s Asher la-Melekh. He writes as follows in his comment to Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2 (emphasis added):

רוב דברי רבנו בפרק הזה מתחלתו עד הלכה ו‘ ועד בכלל, מקורן בברייתא המובאת יבמות מ“ז, אך הודעת עיקרי היהדות לא הוזכרה כלל, וא“כ מנ“ל לרבנו לקבוע כן

R. Feuchtwanger goes on to offer an original solution. Does this mean that he too did not recognize the structure of the Mishneh Torah?

In fact, we don’t need to look at twentieth-century commentaries on the Mishneh Torah to make this point. Right on the page, the Maggid Mishneh states:

ומאריכין בדבר זה: בייחוד השם ובאיסור ע“ז שאינו מבואר שם שיאריכו עמו בזה אבל הדבר פשוט שכיון שאלו הם עיקרי הדת והאמונה צריך להודיעם בברור ולהאריך עמם בזה שהוא עיקר היהדות והגירות

On the Rambam’s words, Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2, that we instruct the convert in basic theology, R. Masud Hai Rakah, Ma’aseh Rakah, ad loc., writes: זה לא הוזכר בברייתא.

In R. Shlomo Tzadok’s commentary to Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2, he writes:

ומודיעין אותו עיקרי הדת: אף שהודעה זו לא נזכרה בש“ס, רבינו סבור שיסוד ועיקר זה, הוא דבר המובן מאליו שצריך להודיעו תחלה

Even after all we have seen, it is possible that Grossman is correct, and all the sources I have cited are mistaken. My only point in citing them is to show that nothing I have said in this matter should be regarded as far-fetched or ignorant, as I offered a reasonable approach to an often-discussed text.

To be continued

Notes

[1] Regarding the Seminary library (or any other Conservative institution), R. Moshe Feinstein was asked if one must return books to them, even if the books will not be used at the institution and the person who has them will learn from them. He replied that “it is forbidden for us to permit gezeilah or geneivah.” See Yad Moshe, p. 86. See, however, R. Menasheh Klein, Mishneh Halakhot 17:155, who writes:

ומיהו היכא דשאל ספר מספריה שהם רשעים ואפיקורסים ויכול ע“י איזה ערמה לעשות שלא להחזיר יש לעיין בדבר, דבס‘דעת זקנים מבעלי התוספות עה“ת פ‘ תולדות עה“פ ויבז עשו את הבכורה כתבו וז“ל, פי‘ מכבר היה מבזה אותה ועל כן לקחה יעקב ממנו, ונמצא בספר ר‘ יהודה החסיד מכאן אתה למד שאם יש ביד רשע ס“ת או מצוה אחרת דמותר לצדיק לרמותו וליטלו ממנו ע“כ. ולפ“ז היכא דישנם ספרים ביד רשעים ואפיקורסים מותר לרמאותם, ולפ“ז כ“ש שאם לוה ולא החזיר בזמנו ויכול לרמותו דלא מיבעיא דלא נפסל לעדות אלא מותר לעשות כן לכתחילה, ולדינא צ“ע

[2] In the days before hebrewbooks.org and Otzar ha-Hokhmah, I often visited the JTS library. It was common to see Orthodox Jews with impeccable standards of kashrut, who would not eat food served in a Conservative synagogue, eating in the Seminary cafeteria.

[3] From Washington Avenue to Washington Street (Jerusalem, 2011), pp. 67-68. I personally was in the Seminary rare book room together with the late R. Ephraim Fishel Hershkowitz.

[4] Regarding Lieberman and Chabad, see here p. 38, where we see that in 1982 Lieberman sent a check for $1000 to Chabad’s Merkos Leinyanei Chinuch. On p. 39, a section of his will is published which shows that he left $10,000 for this same charity. This was called to my attention by Nochum Shmaryohu Zajac.

Zlotnick’s loyalty to his rebbe, Lieberman, was legendary. Unfortunately, this led to a slightly unpleasant experience for me, which I think is worth recording for it shows how sensitive Zlotnick was to the memory of Lieberman. Here is page 23 of Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox; look at note 83.

Not long after the publication of Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, I was at a wedding and someone came over to me to say that Professor Zlotnick would like to speak to me. I had never before met him and someone had obviously told him that I was there. Upon meeting Zlotnick, and with a few others surrounding us, he very firmly told me that it was a big mistake to include the quotation from Wenger in the book, as it mentions that “many faculty members” have questioned if Lieberman wrote a responsum against women’s ordination. I could not understand what he was talking about. I replied that I cited this passage so as to show that it was mistaken. He did not accept my reply, and insisted that to cite such falsehood, even if to show that it is mistaken, was to give it a legitimacy that it did not deserve. He felt that obviously false statements should simply not be dignified with a refutation. Only after he got this point off his chest, which had obviously been bothering him, were we able to have a nice conversation. For months after the conversation, I occasionally wondered if perhaps Zlotnick was correct.

[5] In Mesorat Moshe, vol. 3, p. 389, R. Moshe Feinstein is recorded as stating that there is no problem using Lieberman’s edition of the Tosefta. R. Moshe adds that since he is religious: אינו חשוד שיזייף את התוספתא.

[6] Document provided courtesy of the Saul Lieberman Archives (ARC 76/8) of the Jewish Theological Seminary Library.

[7] When R. Hayyim Capusi (died 1631) was accused of speaking improperly about the gedolim, he responded as follows (Mikabtze’el 37 [5771] p. 581):

ומה שהוציא דבה עלי שדברתי נגד הגדולים, חלילה לי מרשע, וחס ליה לזרעיה דאבא לבוא בגבורות נגד רבותינו ז“ל

[8] Nachum commented to the last post that “‘slander’ is spoken and ‘libel’ is printed (or news, etc.).” While that is the technical definition, all you have to do is google “slanderous article” and you will see that “slander” is also generally used for printed material. Incidentally, when it comes to the word דִבׇּה, which means “slander” in biblical Hebrew, it has a very different meaning in medieval texts. “As Jacob Klatzkin [in his Thesaurus] notes, dibbah in medieval Hebrew does not mean ‘slander,’ but rather a false claim, nonsense, or absurdity.” Y. Tzvi Langermann, “Rabbi Yosef Qafih’s Modern Medieval Translation of the Guide,” in Josef Stern, et al., eds., Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed in Translation(Chicago, 2019), p. 268.

In the last post I discussed the use of the word “strange” in describing earlier opinions. On p. 270, Langermann mentions how in translating a particular word from the Arabic, which the Rambam used with reference to certain aggadic opinions, while Pines uses “incongruous” and Ibn Tibbon uses “megunneh”, R. Kafih uses “muzar”. Here is the section from Guide2:30 in R. Kafih’s translation:

אבל מה שתמצא לשונות מקצת החכמים בקביעת זמן מצוי קודם בריאת העולם הוא תמוה מאד, כי זוהי השקפת ארסטו אשר בארתי לך שהוא סבור כי אין לתאר לזמן התחלה, וזה מוזר . . . אמר רבי יהודה ב“ר סימון מכאן שהיה סדר זמנים קודם לכן, אמר ר‘ אבהו מכאן שהיה הקב“ה בורא עולמות ומחריבן. וזה יותר מוזר מן הראשון

R. Kafih himself uses this word in describing views of his predecessors. See his commentary to Hilkhot Shabbat 16:17, note 29, where after mentioning how virtually all prior commentaries understand a passage in the Rambam, he writes:

וזה מוזר ומופלא ביותר

Abarbanel often uses the words זר and even זר מאד when discussing earlier interpretations. He also speaks this way when referring to talmudic and midrashic passages. See e.g., Yeshuot Meshiho, vol. 2, ch. 5 (p. 108 in Oran Golan’s 2018 edition):

ואמנם מה שאמר רבי חנינא . . . הוא מאמר זר מאד

See also his commentary to Joshua 24:25:

ובדברי חז”ל (מכות פ”ב דף י”א ע”א) בספר תורת הא-להים, ר’ יהודה ור’ נחמיה, חד אמר אלו שמונה פסוקים שבתורה, וחד אמר אלו ערי מקלט, ושניהם דעות זרות מאד

I could cite many more such examples. See also Eric Lawee, Isaac Abarbanel’s Stance Toward Tradition (Albany, 2001), p. 95.

[9] Bikkurim 1 (1864), p. 16.

[10] Introduction to his translation of Leopold Zunz, Toldot Rashi (Lemberg, 1840), p. 12 (unnumbered; the first word on the page is שרשי). In the Jewish Encylopedia entry on Bloch, it says as follows about this work:

Besides the above-mentioned works, Bloch also translated into Hebrew Zunz’s biography of Rashi, to which he wrote an introduction and many notes (Lemberg, 1840). This work bears unmistakable traces of decadence, both in style and virility.

I have no idea what this last sentence is supposed to mean.

[11] Grossman writes that the terms “are taken from an explicit passage of the Talmud in Rosh ha-Shanah 17a which lists these three classes of heretics as those who lose their portion in the World to Come”. Here is the talmudic passage:

אבל המינין והמסורות והאפיקורסים שכפרו בתורה ושכפרו בתחיית המתים . . . יורדין לגיהנם ונידונין בה לדורי דורות

Contrary to Grossman, from the language of the Talmud in the standard Vilna edition it would seem that what we have here are not three categories of theological heretics, but two: מינין and אפיקורסים. The Talmud defines אפיקורסים as those who deny the Torah and the Resurrection. See R. Abraham Abba Hertzl, Siftei Hakhamim, ad loc.

מדנקט הש“ס “שכפרו“, ולא נקט “ושכפרו” בתורה, כמו שנקט באחרינא משמע קצת דבחד מנה להו, והאפיקורסים שכפרו בתורה

The Rambam, Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:6, sees אפיקורסים as separate from the two types of kofrim, rather than seeing kofrim as explaining what an epikorus is. Presumably, the Rambam’s version of the Talmud read like the Munich manuscript: והאפיקורסין ושכפרו. In other words, this version explicitly distinguishes between the epikorsim and the kofrim, creating separate categories. This distinction is noted in the Soncino translation of the Talmud. R. Raphael Rabbinovics, Dikdukei Soferim, ad loc., notes that the Munich version is found in Ein Yaakov and all rishonim, and is the correct text. (I wonder if indeed all rishonim have ושכפרו)

The Koren edition, while keeping the standard text of the Talmud – והאפיקורסים שכפרו בתורה – provides this incorrect translation: “But the heretics; and the informers; and the apostates [apikorsim]; and those who denied the Torah; and those who denied the resurrection of the dead.” If Koren is translating in accordance with the Munich manuscript, then this should have been noted, as והאפיקורסים שכפרו בתורה cannot be translated as: “and the apostates; and those who denied the Torah,” as if we are dealing with two separate categories. I also do not like the translation of epikorus as “apostate,” as today, most people understand “apostate” to mean an actual meshumad, but this is not what we are dealing with.

ArtScroll also translates incorrectly: “But the sectarians, the informers, the Apikorsim, those who denied the divinity of the Torah, those who denied the resurrection of the dead.”

Steinsaltz translates the passage properly:

והאפיקורסים המזלזלים בתורה ובחכמיה שכפרו בתורה

[12] Yesod Mishneh Torah, Sefer Madda, p. 242.

[13] See Guide 1:35.

[14] See Iggerot ha-Rambam, ed. Shilat, vol 2, p. 578:

ושם אלהים אחרים לא תזכירו וכו‘, כי אשר לו קומה הוא אלהים אחרים בלא ספק

[15] Despite the Rambam’s statement in this letter, we know that even with regard to halakhic matters, the Rambam’s originality far exceeds the numerous instances where he mentions that he is offering his own opinion. See my Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters (Scranton, 2008), pp. 79ff.

[16] R. Kanievsky, Shekel ha-Kodesh, introduction.

[17] Emet le-Ya’akov al ha-Torah, p. 16. The following appears in a note, ibid., and is designed to soften what R. Kamenetsky wrote:

בשיחה פרטית הסביר רבינו כוונתו “שעל פי ידיעותיו בפילוסופיא למד כן בחז“ל”.

Yet this explanation is entirely at odds with what R. Kamenetsky wrote in Emet le-Ya’akov, that what appears in the first four chapters of Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah is not based on Torah sources.

[18] Published in Sinai 11 (Nisan-Elul 5707), pp. 11-12 (called to my attention by R. Chaim Rapoport). In Sefer ha-Zikhronot (Har Bracha, 2003), p. 288, R. Tzadok writes:

ולא היה ראוי לו לקבוע ידיעת עניינים כאלה בהלכות יסודי התורה שלו כלל, דברים שאינם צריכים למאמיני התורה לידיעתם, וכל שכן שהרבה מדבריו אינם אמת כפי דעת חכמיהם היום. והכלל, מה לדברי חכמי אומות העולם עם דברי התורה שמן השמים, לעשות דבריהם יסודות לתורה. וכל מה שאסף שם הם מדברי חכמי אומות העולם

[19] Even though the Rambam does not mention instructing future converts in the Thirteen Principles, this is what is done nowadays. Yet what happens if someone converted while holding a belief that violates one of the Principles? Is the conversion valid? This interesting question is discussed by R. Eliezer Ben Porat, who claims that when it comes to most of the Principles—the ones not dealing with God’s essence—even the Rambam would regard the conversion as valid ex post facto. See “Ger she-Ta’ah be-Ehad me-Ikarei ha-Emunah,” Kol ha-Torah 67 (Nisan 5769), pp. 313-316.

[20] Mahaneh Hayyim, Yoreh Deah 2, no. 25 (p. 139).

[21] “Inyanei Gerut,” Or Torah, Adar 5770, p. 540.

[22] “’Ein Lo Helek’: Matarat ha-Rambam bi-Keviat Yud Gimmel Ikarei ha-Emunah,” Masorah le-Yosef 8 (2014), p. 490.

[23] Torat ha-Emek 12 (5764), p. 42. See also Pachter, “Ein Lo Helek,” p. 497:

מטקס קבלת הגר המפורט בהלכות איסורי ביאה, שהבאנו לעיל, שמוכח ממנו שאין צורך בקבלת כל י”ג העיקרים כדי להכנס לכלל ישראל

[24] Ex post facto, if the future convert was not instructed even in the basic principles required by the Rambam, it seems that the conversion would still be valid. See R. Moshe Feinstein, Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Deah 3, no. 106:

וגם מצינו עוד יותר שאף שלא ידע הגר שום מצווה הוא גר, דהא מפורש בשבת דף סח ע“ב גר שנתגייר בין הנכרים חייב חטאת אחת על כל מלאכות של כל השבתות ועל הדם אחת ועל החלב אחת ועל עבודה זרה אחת. הרי נמצא שלא הודיעוהו שום מצווה אף לא עיקרי האמונה ומכל מקום הוא גר

[25] R. Moshe Maimon called my attention to this.

[26] R. Cohen has also published Ha-Emunah ha-Ne’emanah (Brooklyn, 2012). It is obvious that at times in this book he is responding to what I wrote in Limits (and he also deals with many of the sources I cite). While I am not mentioned by name, I am apparently included among the משמאילים referred to on p. 5 (see Limits, pp. 7-8)

[27] Toldot ha-Poskim, vol. 3, p. 212 (emphasis added).

[28] R. Mayer Twersky, in his discussion of the Hilkhot Issurei Biah 14:2, states that the Rambam’s source is Yevamot 47b, and adds: אם כי הרמב“ם הרחיב את הדברים. See “Im Benei Noah Nitztavu be-Mitzvat Emunah o Lo,” Beit Yitzhak 37 (5765), p. 529. In the continuation of the article, R. Twersky makes the argument, which he acknowledges that at first glance is מאד מחודש, that for the Rambam non-Jews are also obligated to believe in the Thirteen Principles. In Limits, p. 22, I cited R. Zvi Hirsch Broide as saying the same thing.

[29] Regarding the Rambam’s instructions for a convert, see most recently Menachem Kellner, “The Convert as the Most Jewish of Jews? On the Centrality of Belief (the Opposite of Heresy) in Maimonidean Judaism,” in Jewish Thought 1 (2019), pp. 37ff.