The Physical and Spiritual Light of Yom Kippur:

Reinstating a Lost Minhag to Enhance the Spirituality of Today’s Synagogue

by: Rabbis Aaron Goldscheider & Barry Kornblau*

Introduction

“Or Zarua la’tzadik – Light is sown for the righteous.” Each year, we begin our Yom Kippur prayers with these repeated, resounding words which Aruch Hashulchan tells us refer to “great matters that are beyond explanation.” If there is one evening of the entire Jewish year when we most seek the great, inexplicable light of God’s shechina, it is Yom Kippur eve. We enter the synagogue with great expectations, to feel close to the Divine, and to feel the warmth of His light and presence. As we say throughout the penitential season, Hashem ori ve’yishi – God is my light and salvation.

Below, we shall see that rabbinic literature prescribes the lighting of candles in the synagogue on Yom Kippur eve. We believe that, for many, reinstating this practice could enhance the spirituality of Yom Kippur eve.

An ancient practice

The practice we seek to reinstate is neither the kindling of Yahrzeit candles, nor the lighting of candles lit by women at home on each Shabbat and Yom Tov evening, including Yom Kippur eve. Rather, it is a third practice – usually not seen here in the United States – that dates back nearly two millennia, to the Mishna. Let us consider the Misnha (Pesachim 4:4 in its entirety, which begins with the custom of candle lighting in the home:

מקום שנהגו להדליק את הנר בלילי יום הכפורים – מדליקין; מקום שנהגו שלא להדליק – אין מדליקין

A place where they have practiced to kindle the light on Yom Kippur eves – they kindle.

A place where they have practiced not to kindle – they do not kindle.

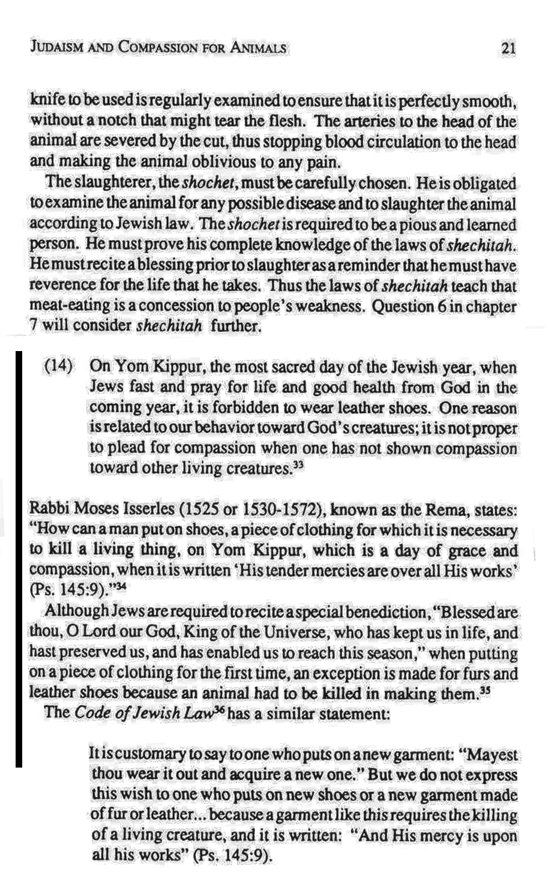

The Tosefta and both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds all explain that these differing practices regarding whether to kindle lights in private homes are both intended to prevent marital relations on the night of Yom Kippur, when that activity is forbidden. The custom to kindle was intended to remind a couple to refrain from marital relations on Yom Kippur eve by creating a lit setting in which such relations are forbidden by Talmudic law, and in which people would be naturally sexually reticent.[1] The custom not to light on Yom Kippur eve, on the other hand, was intended to diminish the husband’s desire for relations with his wife by eliminating the light which allows him to see her and thereby desire her.

Having considered differing practices regarding lighting in private homes, the Mishna goes on to discuss the uniform practice of lighting in public venues – the main focus of this post at the Seforim blog:

ומדליקין בבתי כנסיות ובבתי מדרשות. ובמבואות האפלים, ועל גבי החולים

They kindle in synagogues, study halls, and dark alleyways, and near the ill.

The Tosefta (Pesachim 3:11) expands this list to include other public places such as inns, bathhouses, and restrooms (or, according to one interpretation, mikvaot.) The need to illuminate these various public locations is strictly practical: so people can see where they are going, what they are doing, do not trip, can relieve themselves, immerse themselves in a mikvah,[2] and the like. Since the above sources generally confine themselves to rules on halachic, not practical matters, the Jerusalem Talmud (Pesachim 4:4) explains that this last phrase of the Mishna teaches a halachic point, as well: namely, that even where kindling in private homes is forbidden, kindling in public venues is permitted since there is no concern for marital relations occurring in such settings.

The Mishna, Tosefta, and Talmuds, then, note the uniform practice of kindling lights in synagogues and study halls on Yom Kippur eve. It is a practical matter, whose halachic background relates to the specific issue of the prohibition of marital relations on Yom Kippur. This was true beyond the Talmudic period, as well. R. Eliezer b. R. Yoel HaLevi in Sefer Ravyah (section 528) states explicitly that his community did follow the Talmudic custom to kindle lights in synagogues and study halls, relating this kindling to the Talmudic concerns.[3]

Rosh and the Establishment of a Halachically Mandated Lighting

The halachic works of French Jewry, however, invest the kindling of lights on Yom Kippur with symbolic, ritual, and mandatory meanings. In 11th Century France, for example, Machzor Vitri (Seder shel Yom Hakippurim) describes the formal minhag in his community to kindle lights on Yom Kippur, and provides a Midrashic basis for this custom [the Machzor Vitri also records that the Geonim followed this custom as well]. The Midrash (Tanchuma YaShan 24, P. Emor) asserts that God does not require the mitzvoth of Man, and that the light of the menorah in the Temple is therefore for Man’s benefit – to protect him – and not for God’s benefit. Similarly, since Proverbs 20:27 likens a person’s soul to a candle, Machzor Vitri concludes that kindling lights on Yom Kippur protects. Machzor Vitri, however, does not detail that protection or how it connects to Yom Kippur.

In 13th Century France, Rosh (Yoma 8:9) also recognizes this minhag, indicating that an abundance of candles were typically lit in synagogues. Unlike Machzor Vitri, however, Rosh places this custom into a broader and more familiar halachic framework, namely, kavod Yom Tov. To do so, he begins by citing the Talmud’s requirement (b. Shabbat 119a) to wear clean clothes on Yom Kippur to honor the day in the absence of food and drink through which one honors other holidays.Then, he cites Targum Yonaton to Isaiah 24:15 to show that kindling lights is a form of honoring God. Therefore, he concludes, “yesh le’chavdo (one should honor it)” through all means considered to be honor. For Rosh, kindling lights on Yom Kippur eve fulfills this halachic requirement to honor the day. Rosh’s son, the author of the Arba’ah Turim, follows the approach of his father in this area.

Kol Bo (early 14th Century France and Spain)(sec. 68) introduces two further practical considerations favoring this kindling. First, the recitation of the less familiar Yom Kippur prayers “all day and night” necessitates lighting candles in synagogues. Second, such a candle can be used to fulfill the special halachic requirement of ner she’shavat for the havdalah candle used at the close of Yom Kippur.

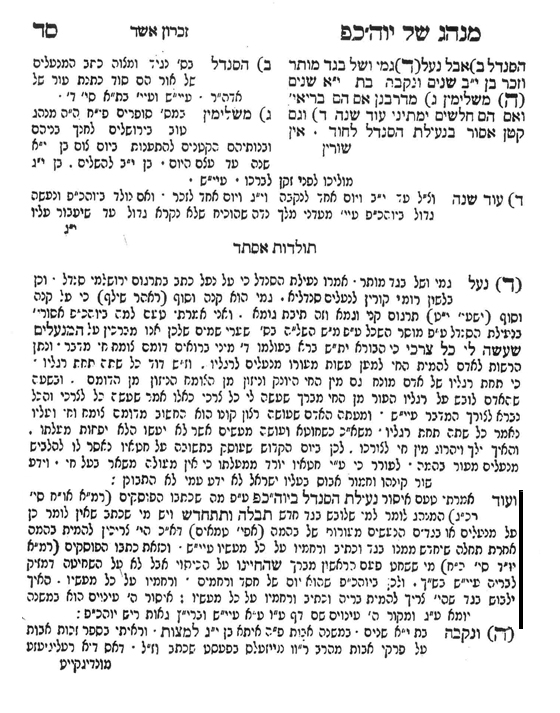

Mordechai equates the lighting with the judgment of one’s soul

Rosh’s immediate contemporary,R. Mordechai b. Hillel Ashkenazi in his Mordechai, (comment #723 to b. Yoma) provides an entirely different basis for this kindling.17 As we shall see, his rationale will take us far away from the issues of honoring Yom Tov and the practical considerations we have seen so far. It is noteworthy that Mordechai prefaces his novel explanation by stating his conscious intent to strengthen this minhag. As we shall see, Mordechai succeeded in this regard, perhaps beyond his own expectations.

Mordechai begins by quoting a statement from the Talmud (b. Horiot 12a, b. Kritut 5b) indicating that if one wants to see if he will live out the year, he should light a candle and place it in a windless room from Rosh Hashana until Yom Kippur. If the flame lasts, then he will live out the year. (Below we will discuss this practice in light of the Torah prohibition of nichush (divination).) Mordechai rules that “in our time, the practice is to kindle a candle on Yom Kippur for every person since it is the gmar din (the final day of judgment).” Apparently, Mordechai means that, since Jews in his time no longer lit candles during the entire period of judgment from Rosh Hashana to Yom Kippur, we symbolically include that entire time period by lighting a candle at its close, on Yom Kippur.

In late 14th Century Germany, R. Yaakov Moelin in Maharil (Hilchot erev Yom Kippur) cites Mordechai, suggesting that the lighting is a personal obligation that symbolizes the soul of man standing before God on the day of judgment, Yom Kippur. He also notes that the practice was for only men and boys to light but not women or girls, providing a number of homiletic and halachic suggestions for why this might be so. The simplest of them is that a married woman fulfills her obligation through her husband’s lighting. Maharil’s student Mahariv (Responsa Mahiri Weil 192) also elaborates on these matters, and prohibits the then common practice of instructing a gentile to rekindle one’s candle that went out on Yom Kippur.

Codification in Shulchan Aruch, Rema and beyond

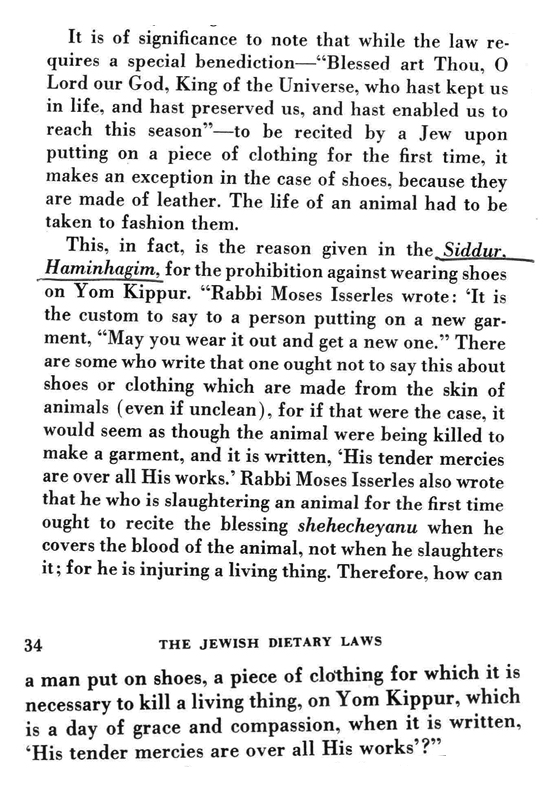

How are the differing traditions of Rosh and Mordechai reflected in the voices found in the standard code of Jewish Law, Shulchan Aruch? R. Yosef Karo cites Mordechai’s approach in his Beit Yosef, but his final codification in Shulchan Aruch reflects the tradition of Rosh; i.e., there should be lights in the synagogue and elsewhere, not that there is an individual obligation to kindle such lights.

In his glosses to the Beit Yosef and the Shulchan Aruch, however, Rema (R. Moshe Isserles) codifies the approach of Mordechai, mandating an individual lighting. As he does so, he adds further stringencies to this kindling. For example, Rema rules that if one’s light is extinguished on Yom Kippur, one must relight it at the conclusion of Yom Kippur and allow it to burn down completely. Similarly, although one whose light burned throughout Yom Kippur could extinguish it out at the end of Yom Kippur, one whose candle went out during Yom Kippur must accept upon himself that neither he nor others will ever extinguish his candle at the end of Yom Kippur. Apparently, these build upon an implication of Mordechai’s Talmudic source; namely, that it is a bad sign if one’s candle goes out on Yom Kippur.

A century later, R. Mordecahi b. Abraham Jaffe in his Levush accepts these rulings of Rema, and adds a further stringency based upon the reasoning of Machzor Vitry. First, he sharpens Machzor Vitry’s reason of “protection” by indicating that the Yom Kippur eve light kindled in the synagogue atones for the soul of the one who lights it. Therefore, he (and subsequent authorities, as well) prohibits lighting a candle for a meshumad (an apostate) so that his soul cannot gain an atonement which it does not deserve.

These varied codifications of the practice to light candles in the synagogue by Tur, Beit Yosef, Shulchan Aruch, Rema, and Levush both reflected and contributed to its spread to all of world Jewry. Indeed, in his comments to the Shulchan Aruch, Magen Avraham notes that concerns about fire safety had prompted a widespread practice to hire a Gentile to guard the synagogue throughout the night of Yom Kippur. That, in turn, prompted him to decry infractions of the regulations pertaining to what such a Gentile may be instructed to do in the context of the laws of Yom Kippur.

So far, then, we have seen at least six separate reasons to kindle candles on Yom Kippur eve in the synagogue (in addition to Yahrzeit and Yom Tov candles lit at home): to protect (Machzor Vitri) or gain atonement (Levush); to fulfill the halachic obligation to honor Yom Kippur day (Rosh); to dramatize the final judgment for the forthcoming year that is given for each person on Yom Kippur (Mordechai); and to address practical issues of having a ner sh’shavat and to provide adequate illumination for the extended, unfamiliar nighttime prayers of Yom Kippur (Kol Bo).

A theoretical problem becomes a practical one

Before continuing to follow this practice’s further development, let us return to a problem in Mordechai’s Talmudic source. It indicated that if one lights a candle at Rosh Hashana time which remains lit until Yom Kippur, then this is a sign that one will live out the year. In his comments to Horiot 12b, Maharasha (16th C) states the problem succinctly: “This practice is apparently forbidden by the prohibition of ‘You must not practice divination’ (Vayikra 19:26). For what reason is this [and other similar practices mentioned in the Talmud] permitted…?”

Maharsha’s answer is that this practice of lighting is permitted because it is an act symbolizing one’s hope for a future good (a siman tov) which does not imply the inverse belief that the absence of that sign will negatively affect the future with certainty. Correspondingly, the Talmud only states the positive sign of the candle remaining lit but does not mention the significance of its going out.

However, the widespread popularity of Mordechai’s approach as well as its intensification over time through the successive stringent rulings of Rema, Levush, and others, created a corresponding intensity about this matter in the minds of Jews. Apparently, the Jewish masses did not maintain Maharsha’s caution about the non-significance of their light going out. Put simply, it appears that ordinary people considered this flame to bear a heavenly sent message regarding their very lives in the forthcoming year. If their flame was extinguished before the end of Yom Kippur, then this implied they would not live out the year. Aruch Hashulchan (OC 610:6) and Mishna Berura (OC 610:14), for example, both write that the Jewish masses were distraught if their candle went out on Yom Kippur. As a result, what was a theoretical problem for Maharsha became a practical problem for these later halachic authorities.

They address this problem in three distinct ways. First, they provide practical ways to avoid seeing whether one’s light goes out. Aruch Hashulchan suggests lighting one’s candle amidst those of others so that one’s own candle is no longer specifically identifiable. (OC 610:6) Similarly, Mishna Berura suggests having a shul representative light all the candles so that people cannot identify their own candle. Second, while still encouraging individuals to light their candles, Aruch Hashulchan exhorts the people to be “whole with your God,” and that “it is not becoming for the Holy People [of Israel] to walk in the ways of divination.”

Finally, Aruch Hashulchan also extends the reasoning of Rosh, writing that the lights are not only to honor the day of Yom Kippur, but that “the practice is to honor the King with great lights and this, indeed, is the practice of all Israel, to multiply lights to honor this holy day…in all of the rooms of one’s home, in synagogues, in study halls, in dark alleyways, near the ill, in order that the light should be great and found in all places…”

Where did this centuries old minhag go in the US?

It is clear, then, the preponderance of standard halachic works from the Mishna to the Mishna Berura consider the kindling of candles on Yom Kippur in the synagogue to be the standard, widely practiced, custom. Mateh Ephraim even records its Yiddish moniker, dos gezunteh licht – the light of health and well-being (603:8). And yet in America, this practice has fallen by the wayside.[4] Where did it go? We don’t know for sure. We can conjecture that electric lighting and fire safety concerns in American synagogues displaced it.

Reintroducing a lost minhag, and practical implementation

We believe that the rabbis and synagogue lay leaders should consider reintroducing this beautiful practice to their sanctuaries. This is opportunity for even the most traditional synagogue to do something new and unexpected that is, at the same time, an ancient tradition of our people, practiced for millennia across all the lands of our dispersion. A synagogue already adorned with a white parochet, white kittels and white talitot can now be aglow with the flames of candles lit by each and every member of the synagogue. This will create a unique setting of purity and awe that is conducive to prayer, introspection, and distinct holiness of Yom Kippur itself. [5]

Notes

[1] Interestingly, this reasoning assumes that the prohibition to have marital relations by candlelight was more widely known and observed by the people then the prohibition of marital relations of Yom Kippur itself.

[2] According to some opinions, a ba’al keri was permitted to immerse himself on Yom Kippur, despite the general prohibition to wash or immerse oneself on Yom Kippur.

[3] It is worth noting Rambam, (Hilchot Shvitat Asur, 3:10) for example, codifies these Talmudic sources and mentions the two varying practices regarding kindling in one’s house, but entirely omits discussion of kindling in all public venues. Magid Mishneh (explains Rambam’s omission in a manner similar to the Jerusalem Talmud’s comment (above), noting that the practice not to kindle in private venues never extended to public ones since couples are not secluded there.

Similarly, writing in Vienna at the turn of 13th Century, Or Zarua elaborates at great length upon many familiar minhagim of Yom Kippur eve, yet entirely omits mention of kindling lights in synagogues.

[4] We have seen a practice in some American synagogues that seems related to the tradition we have delineated; i.e., women light their Yom Tov candles for Yom Kippur in synagogue, instead of at home. There are many reasons, however, why this is not the lighting we are advocating. First, since the days of Maharil, only men have done the lighting we describe, but not women. Second, these women are reciting the blessing for Yom Tov kindling over these candles. Unlike most other Shabbat and Yom Tov evenings, women on Yom Kippur are not at home but rather in synagogue. It would seem, then, that they light where they will be while their candles are lit. Indeed, they may feel it unsafe to leave unattended candles lit at home.

[5] Here are some recommendations for those interested in introducing this practice to their synagogues:

*Dim the electric lighting for Yom Kippur eve if technically possible.

*Each synagogue will need to think creatively about how to arrange the candles to be light, given the layout of its sanctuary. Note that a wide variety of candle holding devices are available for sale today through the Internet and other venues.

*In keeping with the ruling of R. Yosef Karo, candles can be arranged without any correspondence to the number of individuals or families in the synagogue.

*Alternately, in keeping with Ashkenazic tradition, lighting can be done by each individual man on behalf of himself and his family. Women, too, can light their own candle if they wish29. It will be necessary in advance of the holiday to encourage those who will be lighting of the need to participate in this practice. Presumably, this could be done by a letter, a class, at the time of ticket distribution, or in other ways. To accommodate the concern first articulated by Maharil, time would also need to be scheduled for people to do this in an orderly and safe manner prior to the onset of Yom Tov. Coming to synagogue earlier might also encourage congregants to enter Yom Kippur in a more reflective manner, recite tefillah zaka, etc.

*Of course, as Magen Avraham pointed out, each synagogue will need to attend to fire safety concerns within the confines of halacha, as well.

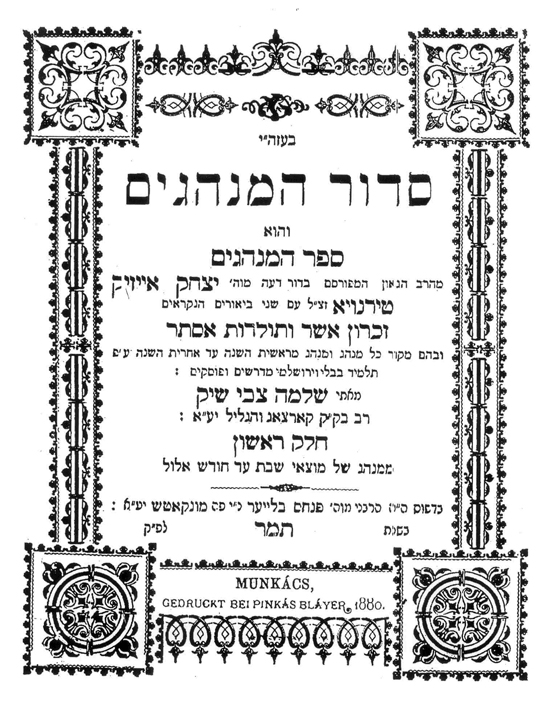

[Ed. note – For Additional Reading: for more on the custom of lighting candles on Yom Kippur, see R. Y. Goldhvaer’s Minhagei HaKehilot, Jerusalem, 2005, 88-96, available here (PDF)]

* Aaron Goldscheider serves as the Rabbi of the historic Mount Kisco Hebrew Congregation in N. Westchester, NY.

Barry Kornblau serves as rabbi of the Young Israel of Hollis Hills-Windsor Park, and the Director of Committees and Operations at the Rabbinical Council of America.