On the History and Development of Nirtza

On the History and Development of Nirtza

By Yaacov Sasson

Yaacov Sasson is a musmach of RIETS, and author of the recently published ספר שש אנכי, available here.

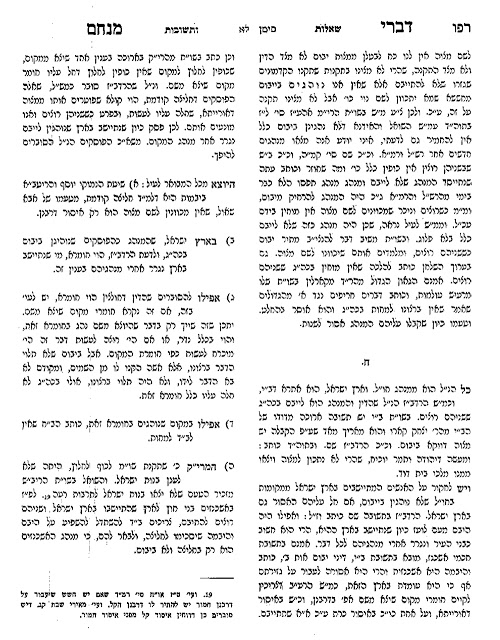

Nirtza is the conclusion of the seder, and as most commonly recited in the Ashkenazi tradition, consists of the following components: the recitation of L’shana Habaa B’Yerushalayim and Chasal Sidur Pesach, followed by the piyutim Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla, Va’amartem Zevach Pesach, Ki Lo Naeh, Adir Hu, and then additional piyyutim such as Chad Gadya and Echad Mi Yodea; the latter two are of later vintage.[1] Nirtza remains somewhat enigmatic, and an analysis of the historical development of Nirtza is helpful to understand its function within the structure of the seder.

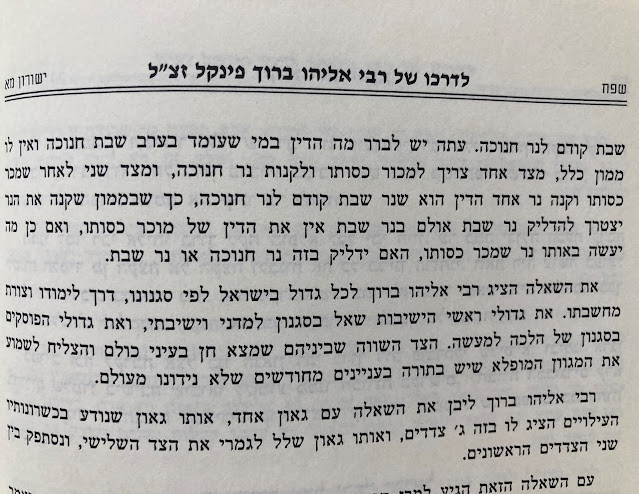

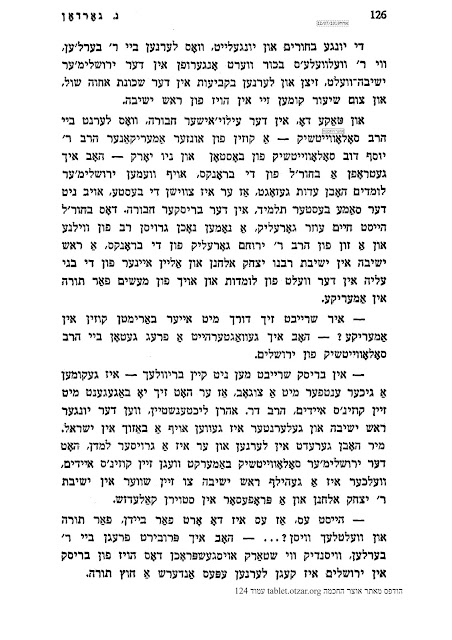

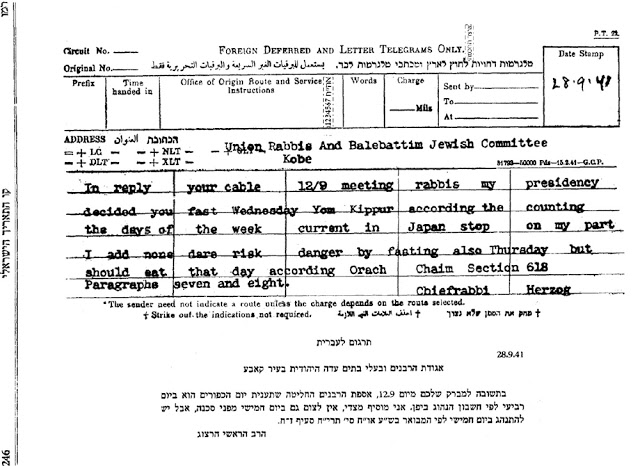

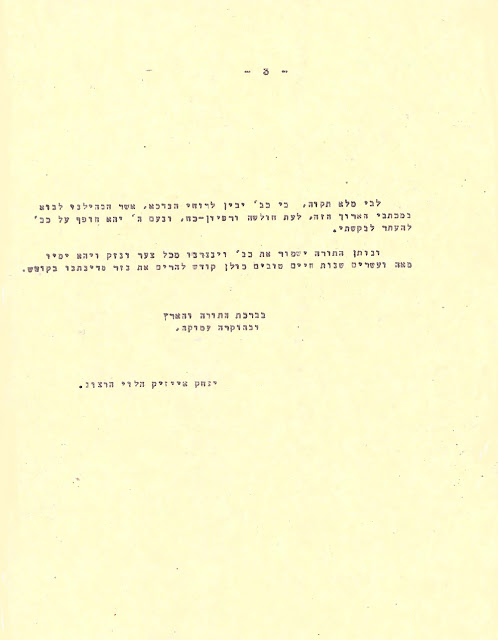

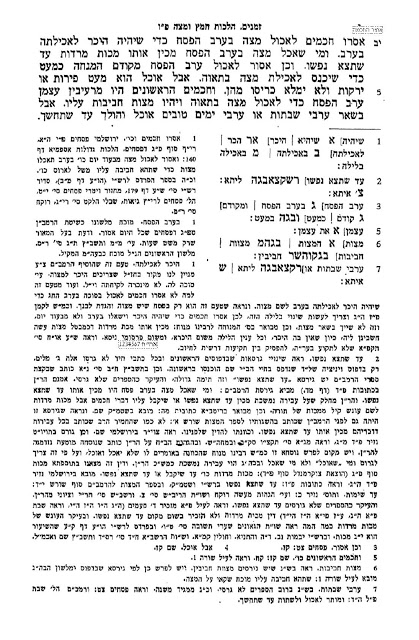

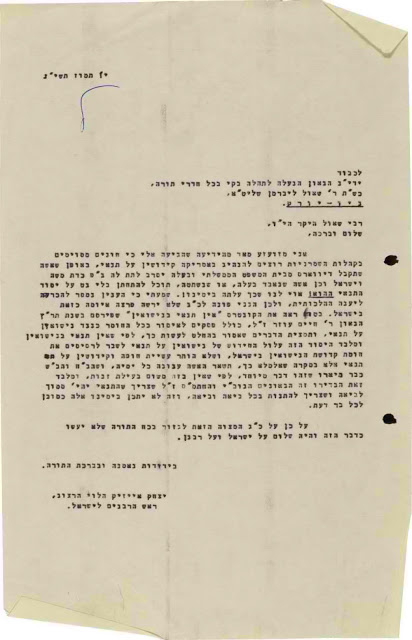

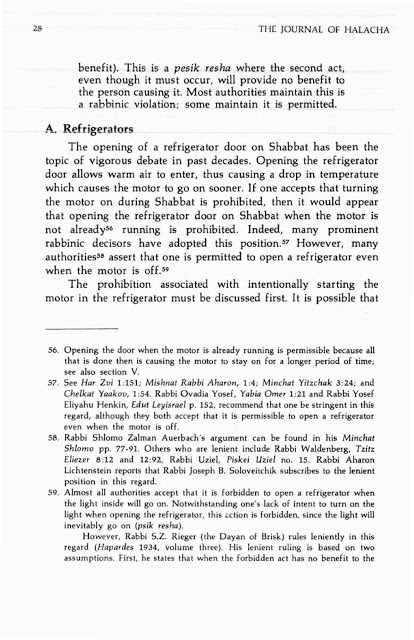

The Leket Yosher, a student of the Trumas Hadeshen, records the Trumas Hadeshen’s simanei haseder, which are more detailed and elongated than the popular “Kadesh Urchatz” simanim. The Nirtza of the Trumas Hadeshen is similar to the current day Nirtza, with one very noteworthy difference. For the end of the seder, beginning with the washing of mayim acharonim, the Trumas Hadeshen’s simanim read as follows:

The Leket Yosher goes on to explain each of these simanim in more detail, and writes[2]:

As such, the Leket Yosher already had the components of L’shana Habaa, Chasal Siddur Pesach, Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla, Va’amartem Zevach Pesach, Ki Lo Naeh, and Adir Hu. However, the Leket Yosher has the piyyutim of Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla, Va’amartem Zevach Pesach, and Ki Lo Naeh before the drinking of the fourth cup, whereas the common practice now is to say these piyyutim after the cup and after Chasal Siddur Pesach.

The recitation of these three piyyutim before the drinking of the cup seems to indicate that, fundamentally, the Trumas Hadeshen and Leket Yosher considered these piyyutim to be part of Hallel, as the fourth cup was instituted over the recitation of Hallel. The content of these piyyutim is mostly hallel and shevach, so it seems reasonable that these piyyutim were originally included in the seder as a part of Hallel, and this is also indicated by the Trumas Hadeshen’s language of “Mosif B’Shvachos Ha-el”, indicating that these piyyutim are indeed a hosafa to Hallel. Thus, within the structure of the seder, these three piyyutim do not function as part of the conclusion of the seder; rather they are actually part of Hallel.

The Leket Yosher places L’Shana Habaa, the piyyut Adir Hu, and Chasal Siddur Pesach after the fourth cup. The distinction between these, which are placed after the cup, and the aforementioned three piyyutim, seems to be that the elements placed after the cup are thematically forward looking, toward the future geula, rather than hallel on past miracles. As such, they are appropriate for Nirtza, which, as mentioned, functions as the conclusion of the seder.[3] While Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla and Va’amartem Zevach Pesach do end with bakashos for the future geula, they are by and large shevach and hallel for past miracles, and thus were considered a hosafa to Hallel.

It is also likely that Chasal and Adir Hu were later additions to the seder, which might constitute an additional reason why they were split from the three earlier piyyutim.[4] It appears from Leket Yosher that Chasal Siddur Pesach was originally a local minhag, so that certainly became widespread later than the three earlier piyyutim. And in the hagada of Rav Yitzchak ben Meir of Dura (author of Shaarei Dura), the seder ended with L’shana Habaa after the final cup, with no recitation of Adir Hu or Chasal.[5] This would indicate that Adir Hu and Chasal became standard later than the three earlier piyyutim, which are included in the Shaarei Dura’s hagada.[6]

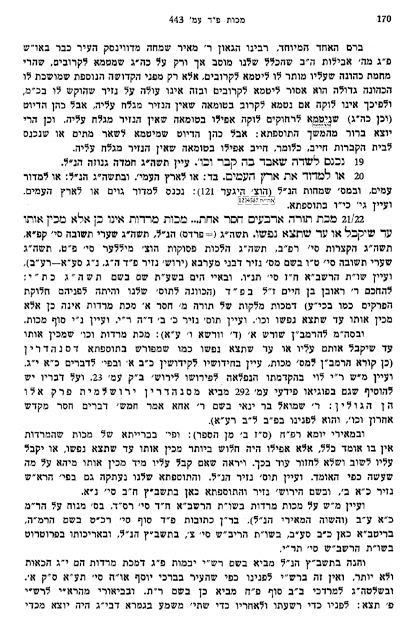

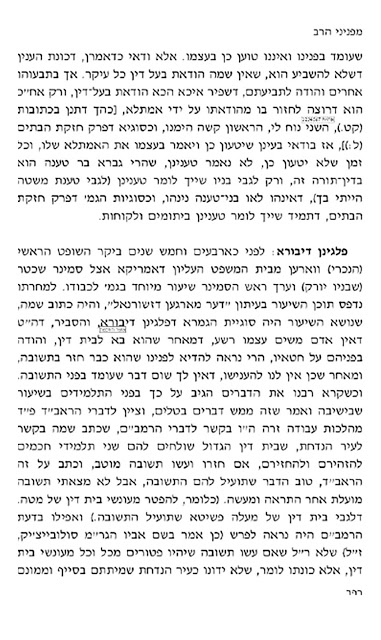

As noted earlier, the widespread practice today is to recite the three piyyutim (Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla, Va’amartem Zevach Pesach, and Ki Lo Naeh) after the drinking of the fourth cup.[7] Maharshal (Shu”t Maharshal 88) objected to the recitation of these piyyutim before the drinking of the cup, because the closing bracha of Hallel should immediately precede the drinking of the cup.[8] Maharshal states that the piyyutim should be recited after the cup, unlike the Tofsei Machzorim that have the drinking of the cup after these piyyutim. Maharshal is cited by the Bach (siman 480), and the Magen Avraham (siman 480) writes that the piyyutim should be recited after the cup, as they are only a minhag. Although Maharshal and the Magen Avraham provide reasons why the piyyutim should come after the cup, it is possible that they fundamentally agree that the piyyutim are an extension of hallel, albeit with technical reasons why they should be recited after the cup.

It should be noted that the Magen Avraham also cites from the Tashbetz (99) that Maharam would recite the piyyutim before drinking the fourth cup, so as not to be thirsty when going to sleep, and this is what is printed in Siddurim. My impression is that, although he brings both opinions, the ikar halacha according to the Magen Avraham is like the opinion of Maharshal, that the piyyutim be recited after the cup.

As noted by Maharshal and the Magen Avraham, the order printed in the Tofsei Machzorim and Siddurim in their time was the recitation of the three piyyutim before the drinking of the cup. And while Maharshal, the Bach, and the Magen Avraham ruled as early as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that the piyyutim should be recited after the drinking of the cup, this ruling was largely not followed for hundreds of years.[9] In my informal survey of printed hagados available online, virtually all printed hagados that I saw through the eighteenth century followed the old order, with the piyyutim before the cup, as presented in the simanim of the Trumas Hadeshen.[10]

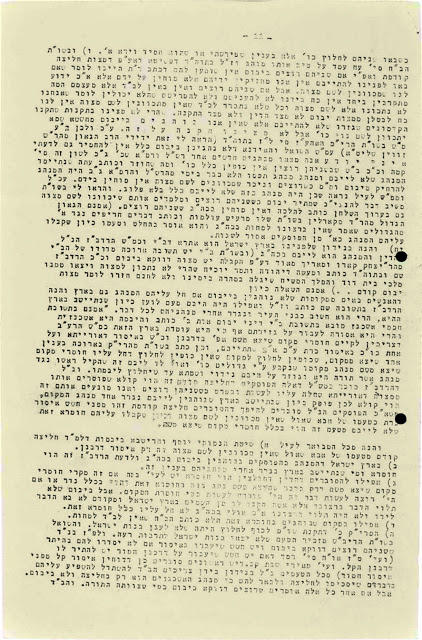

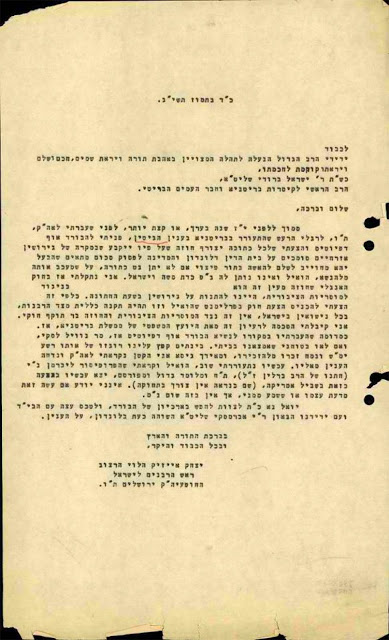

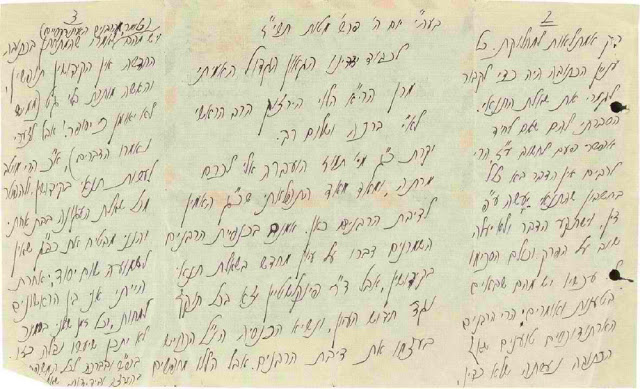

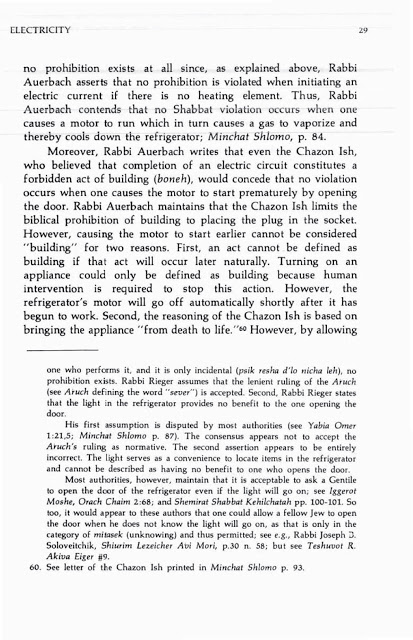

To show just a few examples, this hagada printed in Amsterdam in the late 1700s places the piyyutim directly after the concluding bracha of Hallel, before drinking the cup[11]:

As does this hagada printed in Fuerth in the late 1700s[12]:

There were few hagados in the early 1800s that placed the piyyutim after the cup, with more in the later 1800s, as this practice grew modestly. But even by the end of the nineteenth century, the majority of hagados placed the piyyutim before the drinking of the fourth cup. (Aruch Hashulchan (480:3) also writes regarding the placement of the piyyutim before the cup, that it is so in the Hagados, confirming that this was the standard order through the nineteenth century.) The major shift to placing the piyyutim after the cup took place in the twentieth century, and very much accelerated in the second half of the twentieth century, to the point that today, it is difficult to find a hagada that places the piyyutim before the cup.

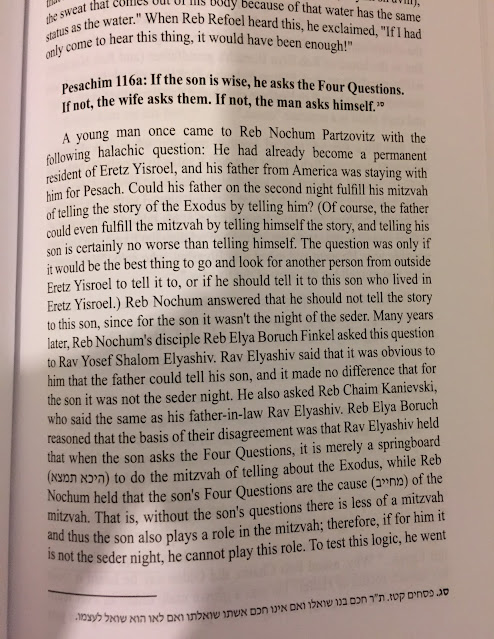

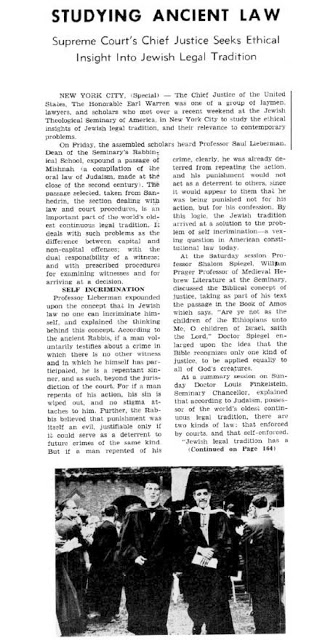

The Maxwell House hagada is the most widely used hagada in America, and has been used by millions of Jews over the past 100 years. Maxwell House also placed the piyyutim before the cup, as late as its 1994 edition. (Below is an image from the 1964 edition.)

However, by the 2015 edition of the Maxwell House hagada, the order was changed, and the piyyutim are now placed after drinking the cup.[13]

Some other new editions of older hagados have also moved the placement of the piyyutim to after the cup. For example, in the 2001 Ahavas Shalom edition of the Shelah’s hagada, they have moved the piyyutim to after the cup, but do inform the reader of the original placement of the piyyutim.

One popular hagada that still places the piyyutim before the cup is the Ktav Publishing House (red and yellow) hagada.[14] This placement is so out of the ordinary in current day hagados, that it leads to questions like this one[15]: “The semi popular Passover Hagadah by Rabbi Nathan Goldberg strangely puts drinking the fourth cup at the seder after starting a couple of songs from nirtzah. I’ve never seen this in any other haggadah, and it seems wrong. The fourth cup was established to go with hallel, and it would make sense then to drink it at its conclusion, and not make an interruption with a couple of unrelated songs. Is this a mistake? Is there some source for this “change”?”

The pendulum has swung so much to the Maharshal’s order, that the questioner is unaware that this was the order in the majority of hagados until a century ago, and that the change went in the other direction; the order more common today is the result of a change. The language of the question is also noteworthy, as “drinking the fourth cup at the seder after starting a couple of songs from nirtzah” would indeed be strange, as would be an interruption of “unrelated songs”. However, if we understand that these piyyutim are actually intended to be part of Hallel, as noted above, the question falls, as the question is based on the assumption that these piyyutim are intended to be part of Nirtza.

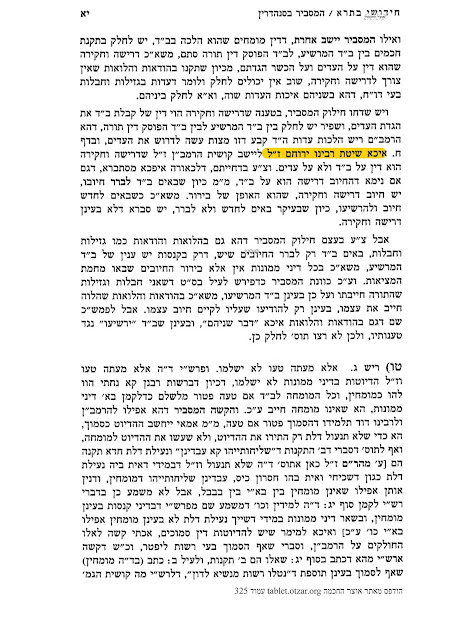

Similarly, the Mesivta (Nusach Ashkenaz) Hagada (p.792) singles out Rav Reuven Margoliyos’s hagada (Be’er Miriam) in noting that Ki Lo Naeh appears there before the drinking of the cup, seemingly also unaware that the majority of hagados were printed that way until the twentieth century.

An interesting question arises: why is it that the ruling of Maharshal and the Bach were largely not followed until the twentieth century, and the custom in the twentieth century shifted so dramatically that the prior custom is now nearly unheard of? One possibility is that this is a “Rupture and Reconstruction” phenomenon, and reflects the shift from mimetic tradition to book-learning halacha due to the rupture in Ashkenazi society caused by the holocaust, a result of which was the de-emphasis of the mimetic tradition. This larger trend was noted by Dr. Haym Soloveitchik in his seminal article in Tradition.[16] A modification of Dr. Soloveitchik’s hypothesis was put forward by Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer, who suggested that the shift to book-learning halacha was a result of the explosion of yeshivos and kollelim in the 20th century.[17] R. Micha Berger has argued that the changes noted by Dr. Soloveitchik began in the 19th century, and “less than a discontinuity that occurred in the mid-20th century, the reconstruction was a long process that was forced to a hasty close[18]”, which seems to fit the phenomenon we have observed here.

Another factor to consider is what R. Joseph Tabory has written, that “the custom eventually disappeared from the eastern European tradition, although it still appears in some haggadot of the western Ashkenazic tradition[19]”, although he does not note what precipitated the change, when the change occurred, or that it has further accelerated in the last century with the demise of Eastern European Jewry.

An additional explanation for the dramatic change in common practice was suggested by my good friend Dr. Josh Lovinger, who noted that the halachic codes themselves may have tended more towards Maharshal’s position as time has gone on. The Magen Avraham, for example, brought the position of Maharshal, as well as the practice of Maharam. However, the Shulchan Shlomo (480:1) requires the piyyutim to be placed after the cup, and the Aruch Hashulchan (480:3) also endorses Maharshal’s position unequivocally.[20] There are however, counter-examples, as Chayei Adam (Klal 130: Hallel) presents both options as legitimate, and Mishna Brura, following Magen Avraham cites both positions. It is possible that the acceleration of this shift was a result of a combination of all of the above factors.

Assuming the three piyyutim are to be recited after the cup, as according to Maharshal, what then is the proper sequence after the cup? Based on the above, that the piyyutim were originally part of Hallel, it would follow that the three piyyutim should be recited immediately after the cup, and before Chasal. Although the piyyutim ought not be recited before the cup for a technical reason, it is reasonable that the piyyutim be placed adjacent to Hallel since they were intended to be part of Hallel. Chasal Siddur Pesach means that the seder is complete, so it would be inconsistent to declare that the seder is complete and then go back to reciting Hallel. As noted above, the three piyyutim are primarily hallel-themed, while Chasal is forward looking, and as such seems to belong after the piyyutim. Additionally, as mentioned above, Chasal was added to the seder later than the three piyyutim, which might be another reason that Chasal was originally placed after the cup. This might be additional reason to recite the piyyutim before Chasal, as they were incorporated into the seder earlier.

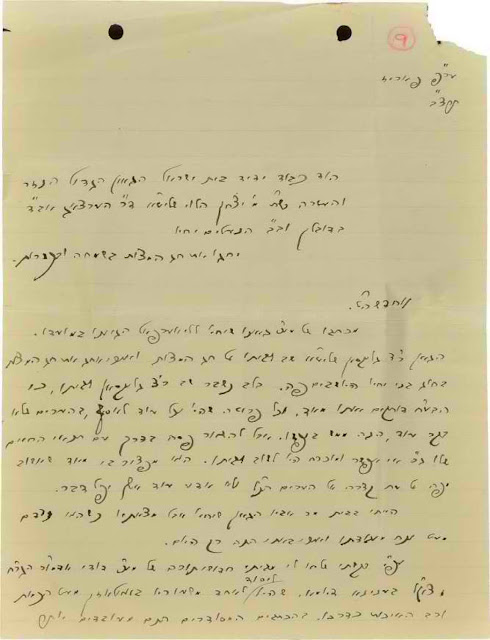

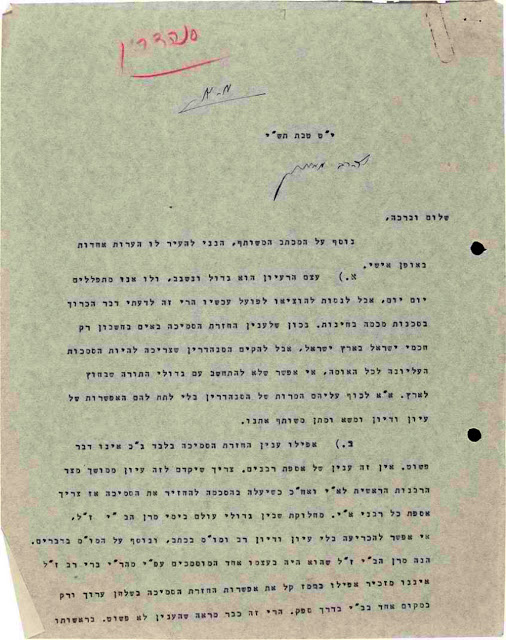

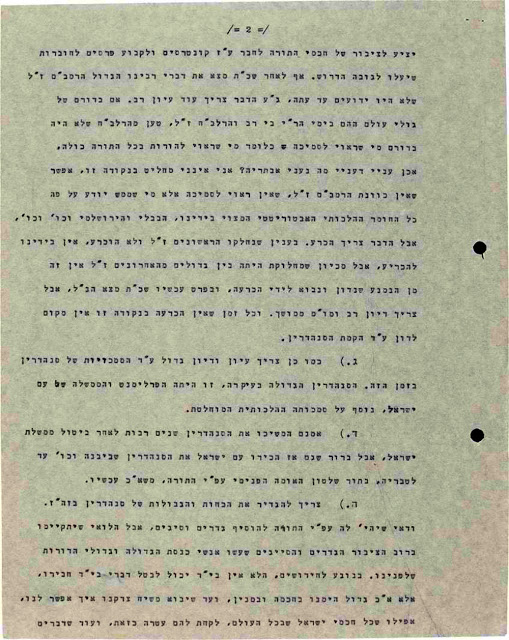

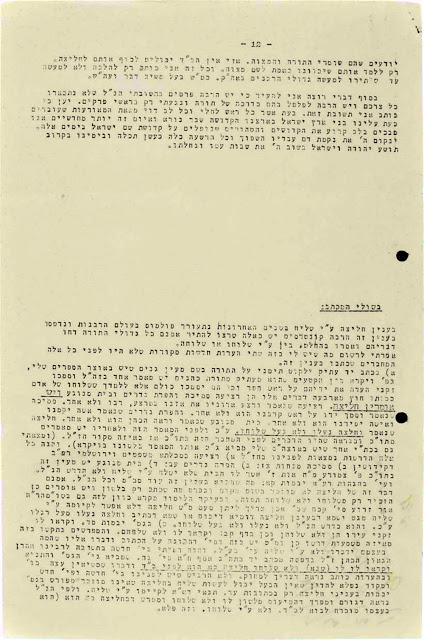

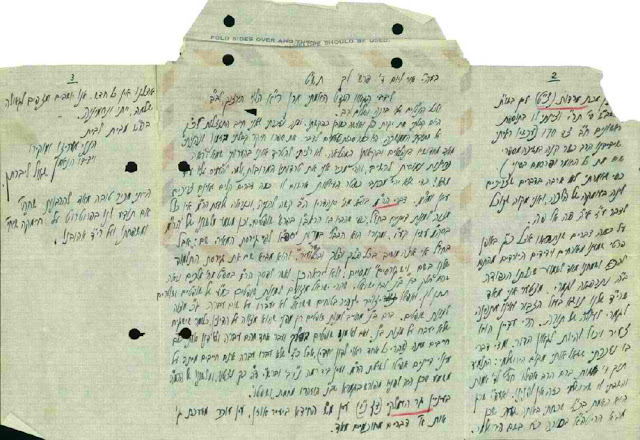

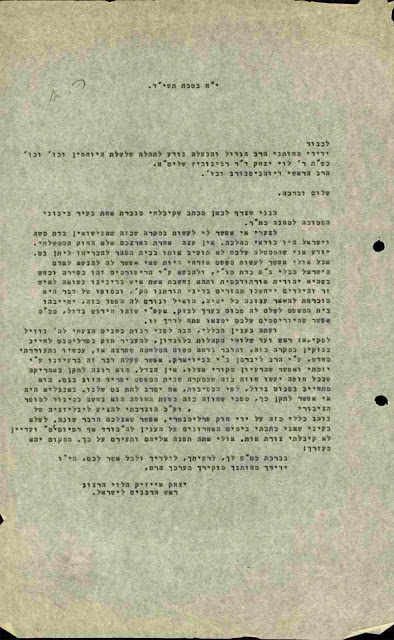

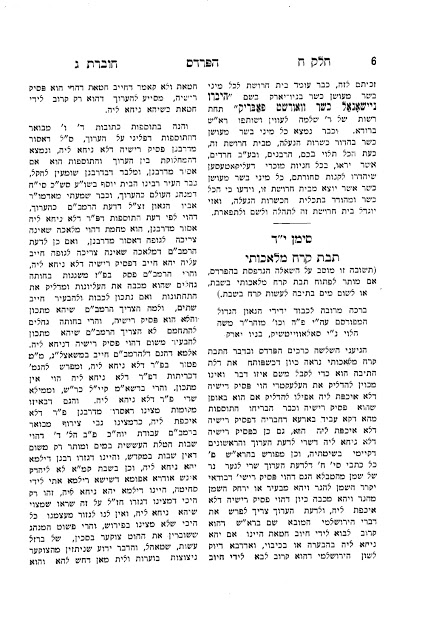

This order, with the three piyyutim after the cup but preceding Chasal, is in fact found in the hagada of Rav Yozfa Shamash, available in manuscript online via the National Library of Israel.[21]

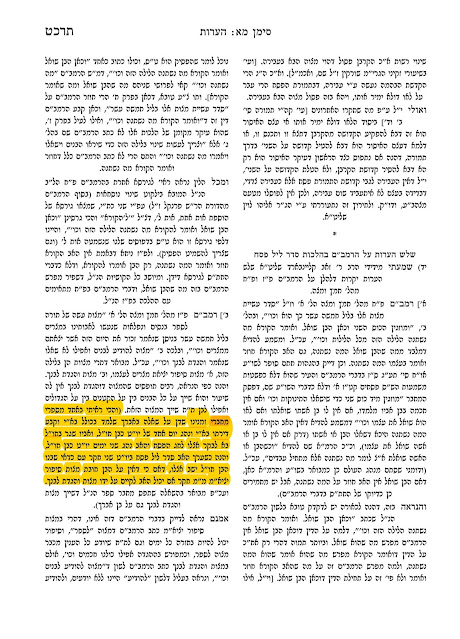

This section is also included in Machon Yerushalayim’s edition of Rav Yozfa Shamash’s Minhagei Vermeiza, in the hagahos to siman 77:

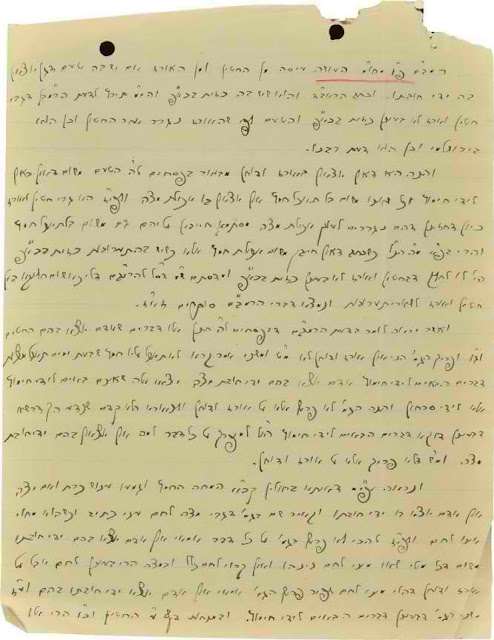

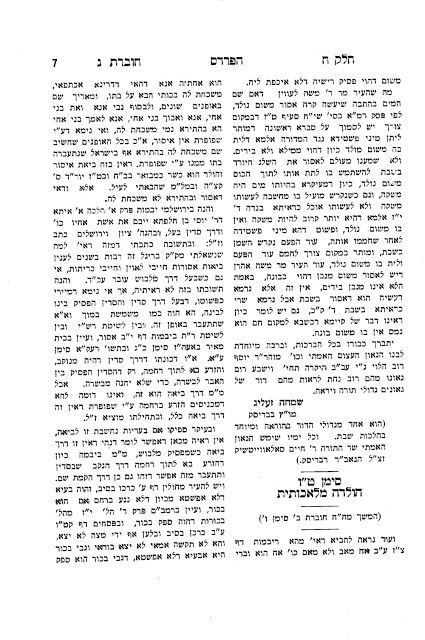

This is also the order presented in Rav Yaakov Emden’s siddur Shaarei Shamayim, with the three piyyutim after the drinking of the cup, and preceding Chasal.[22] Here is Chasal following the completion of Ki Lo Naeh:

However, this order is not the prevailing practice, and is almost unheard of in present day hagados.[23] Although R. Joseph Tabory notes that “Others of the western tradition have…retained a vestige of the western Ashkenazic custom by retaining the Hasel Seder Pesach after the additional songs, rather than immediately after drinking the fourth cup[24]”, it is unclear to me who he is referring to in the present day that has retained Chasal after the additional songs.

The only hagada that I have seen printed in the last 100 years that places these piyyutim after the cup and before Chasal, is the hagada Todas Yehoshua of the Monastryshcher Rebbe, printed in 1935.[25] (There might be others that I have not seen, but they are certainly very few and far between.) Here is how the piyyutim appear in the Todas Yehoshua, with Vahehi Bachatzi Halalya after the cup, and Chasal after the end of Ki Lo Naeh.

The Monastryshcher was one of the earlier Chasidic Rebbes to emigrate to the United States, and OU Press recently published a volume about him, entitled Hasidus Meets America: The Life and Torah of the Monsatryshcher Rebbe, by Ora Wiskind.[26] I contacted the Rebbe’s descendants to inquire why his hagada placed the piyyutim before Chasal, but did not receive a clear answer. However, his great-grandson Rabbi Nachum Rabinowitz pointed me to the Rebbe’s hanhagos, printed in sefer Erkei Yehoshua, and his own practice was not as printed in his hagada. On the first night, he recited the piyyutim after the cup and after Chasal, as is the common practice today. On the second night, he recited the piyyutim before the cup, as was the old minhag. So his personal practice was different on each night, but neither night was consistent with what he printed in his hagada.

The prevailing practice nowadays is to recite the piyyutim after the cup, and after Chasal. The earliest hagada that I have seen with this order is the hagada of Rav Shabsai Sofer (published from manuscript over 20 years ago), that has the three piyyutim after the cup and after Chasal.[27] The vast majority of hagados with the piyyutim after the cup follow this order, and virtually all hagados printed nowadays follow this order. It is not clear to me how this order became dominant. Most published halachic codes, when they state that the piyyutim belong after the cup, do not specify whether they belong before or after Chasal. Shulchan Shlomo appears to be the exception, as it specifies saying the piyyutim after Chasal. This might have contributed to this becoming the prevailing practice, although it is not clear that this would be sufficient to carry the day so decisively. It is possible that the order of Chasal being recited immediately after the cup stuck, even when the piyyutim were moved to after the cup.

Aside from the question of how this became the prevailing practice, there is also the question of whether this practice is reasonable. If the piyyutim are seen as a part of Hallel, then it should make sense to recite them before Chasal, not after. Part of the explanation might be that the recitation of Chasal is intended to connote the end of the formal halachic seder, and as such should follow the drinking of the last cup, and not additional piyyutim which are a hosafa to hallel. However, as noted above, thematically these piyyutim are more similar to Hallel, while Chasal turns the focus towards the future geula, so the placement of these piyyutim remains somewhat ambiguous, and as such is a matter of dispute between different authorities, as noted above.

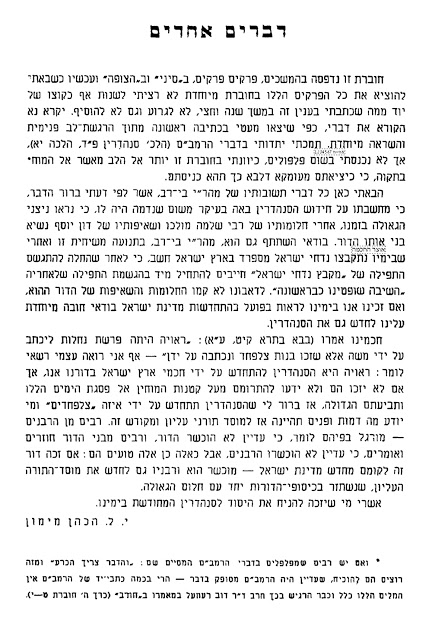

In summary, the Trumas Hadeshen and Leket Yosher place these three piyyutim (Vayehi Bachatzi Halayla, Va’amartem Zevach Pesach, Ki Lo Naeh) before the drinking of the fourth cup, as part of Hallel. This was the Ashkenazi practice for hundreds of years. Maharshal, Bach and other poskim objected to this practice and required the piyyutim to be placed after the cup. This ruling was largely not followed the twentieth century. If the three piyyutim were intended to be part of hallel, it would seem to be reasonable to recite them before Chasal, but the common practice is to recite them after Chasal.

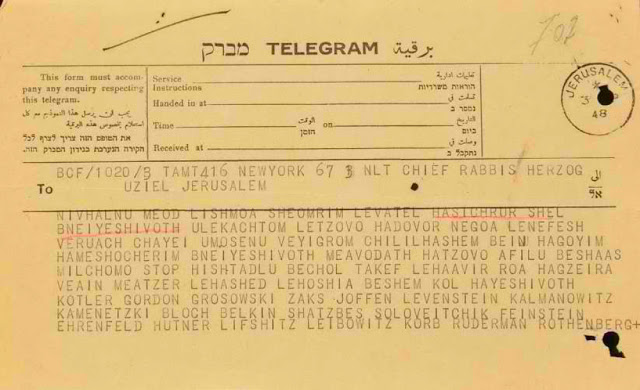

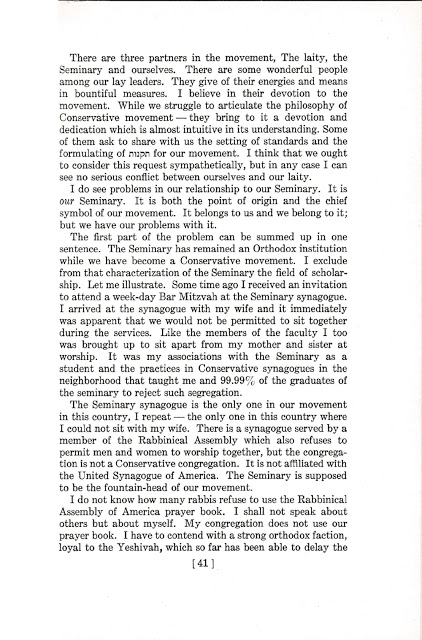

Let us conclude with a Nirtza bakasha found in a hagada manuscript from Baghdad in 1776[28]:

,נרצה כל מי שעושה זה הסדר יזכה לשנים רבות

,נעימות וטובות, לשנה הבאה בירושלים

שמחים כפלי כפלים בקבוץ גלות יהודה ואפרים אמן

[1] See R. Daniel Goldschmidt’s chapter 3, and Hagada Shleima (R. Shmuel Ashkenazi and R. Menachem Kasher) siman 36.

[2] https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=8860&st=&pgnum=155

[3] The 1526 Prague Hagada also contains a version of Adir Hu in German, printed in Hebrew letters, beginning “Almechtiger Gott”.

https://braginskycollection.com/portfolio/prague-haggadah

Hagada Shleima suggests that perhaps the German is the original and the Hebrew (Adir Hu) is a translation, but I have not seen any evidence to support that assertion. Versions of this German Adir Hu also appear in various later hagados, some of which include the refrain “Nun Bau”, for example in the 1725 Herlington Hagada.

https://braginskycollection.com/portfolio/herlingen-haggadah/

This German version is still recited by some in the Yekke community to this day. This version also appears in the Hagada in the original printing of the Shaar Hashamayim siddur with the commentary of the Shelah. (The 2001 Ahavas Shalom edition of the Shelah Hagada has removed the German version.) This German version of Adir Hu did elicit some opposition, such as in Beis Eivel Uveis Mishte (pp18b – 20b) by Rav Shmuel Palaggi, and Kos Yeshuos by Rav Naftali Hertz Fleish (excerpts printed in Min Hagenazim, vol. 3, 1975, p. 96.)

[4] See R. Daniel Goldschmidt’s Chapter 3, where he also notes that Chasal and Adir Hu were later additions.

[5] https://www.loc.gov/item/2022397713

[6] Interestingly, the Shaarei Dura hagada has the recitation of borei nefashos after the fourth cup, in the image shown. This is certainly a scribal error, as a few pages before, when detailing the halachos of the remainder of the seder, it says explicitly that al hagefen is to be recited after the fourth cup. Also noteworthy is that this hagada includes our standard simanim of “Kadesh Urchatz”, but with the addition of a siman “Notel”, denoting mayim acharonim before birkas hamazon.

[7] I am told, anecdotally, that some in the Yekke community still recite the piyyutim before the fourth cup.

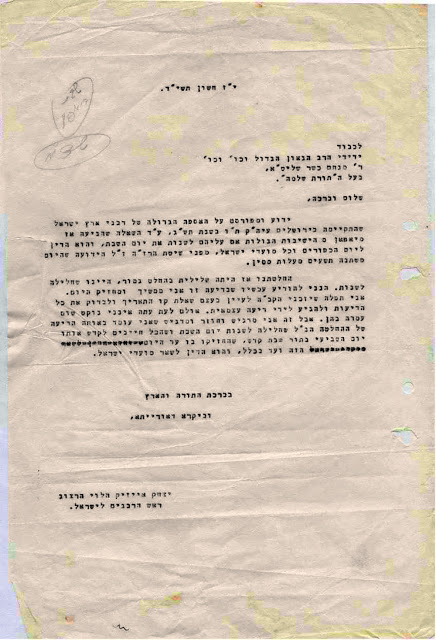

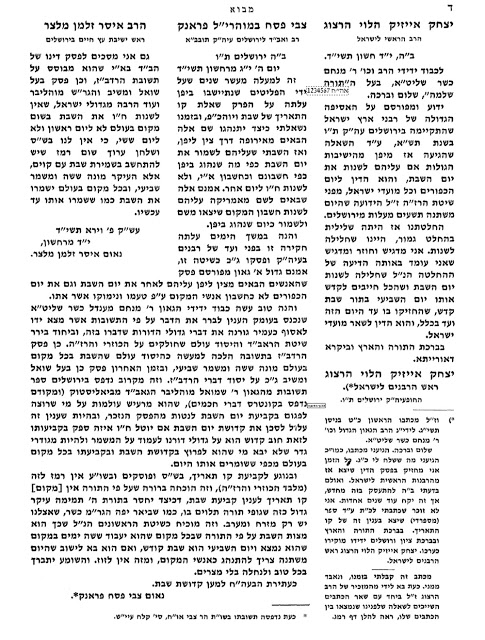

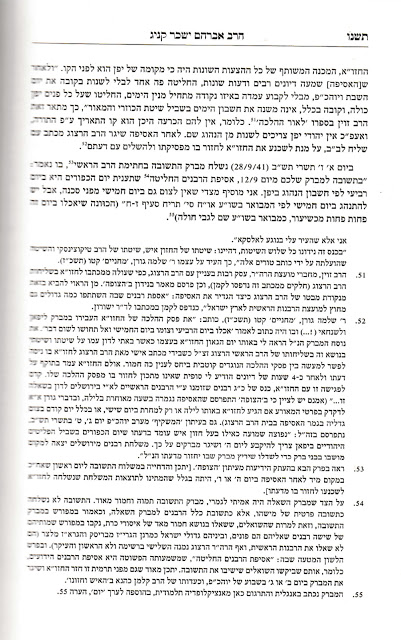

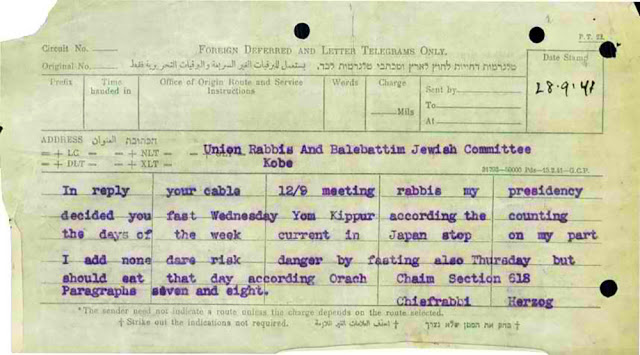

[8] Regarding the closing bracha of birkas hamazon, and the recitation of harachaman before the cup, see my Sos Anochi (siman 26).

[9] My assumption in this statement is that people’s practice generally followed what was printed in their hagados.

[10] One exception that I saw in print is in the siddur of Rav Yaakov Emden, which will be shown below. There were also several exceptions in manuscript that were printed only more recently, such as the hagados of Rav Yozfa Shamash and Rav Shabsai Sofer, also mentioned below.

[11] https://hebrewbooks.org/4889

[12] https://hebrewbooks.org/10550

[13] My attempts to determine who decided to make this change to the Maxwell House hagada were unsuccessful.

[14] https://ktav.com/products/goldberg-passover-haggadah-box-of-50

[15] https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/102127/fourth-cup-after-starting-nirtzah

[16] “Rupture and Reconstruction” by Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, in Tradition 28:4.

[17] In a Symposium on “Rupture and Reconstruction”, Tradition 51:4, specifically pp. 83-84.

[18] https://www.torahmusings.com/2019/08/rupture-and-reconstruction-at-25-years/

[19] The JPS Commentary on the Haggadah, p. 60. My thanks to Dr. Josh Lovinger for bringing this reference to my attention.

[20] Interestingly, Mishna Brura cites both positions, while the Aruch Hashulchan endorsed Maharshal unequivocally. This is somewhat of a departure from what we would expect based on Dr. Soloveitchik’s presentation in “Rupture and Reconstruction”, in which the Aruch Hashulchan typically attempted to justify common practices, while the Mishna Brura tended to value common practice less than did the Aruch Hashulchan.

[21] https://www.nli.org.il/he/manuscripts/NNL_ALEPH990001671700205171/NLI#$FL15383925. This hagada was recently published by under the title Hagada Likutei Yosef.

https://kollelashkenaz.org/publications/haggadah-shel-pesach-the-yosef-yusfa-haggadah/

[22] https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=22619&st=&pgnum=92&hilite=

My thanks to Dr. Josh Lovinger for bringing this reference to my attention.

[23] I would expect that Hagada Likutei Yosef should follow this order, but have not seen a copy thus far.

[24] The JPS Commentary on the Haggadah, p. 60.

[25] https://hebrewbooks.org/2712

This hagada was printed as a fundraiser for Yeshiva R. Chaim Berlin.

[26] https://oupress.org/product/hasidus-meets-america/

[27] My thanks to Dr. Josh Lovinger for bringing this reference to my attention.

[28] Hebrewmanuscripts.org/hbm_712.pdf