Depression Angles

Depression Angles

By William Gewirtz

Introduction:

Depression angles measure the level of darkness or illumination prior to sunrise and, in a parallel fashion, after sunset.

There are two halakhic disagreements that might appear to relate to the use of depression angles. First, there is a long-standing argument about what defines the transition from one day to the next and what is (merely) an indicator that the transition has occurred. Some consider the appearance of three stars as the basis of a definition, while others assume that darkness is defining, with the appearance of three stars merely being an indicator that a specific level of darkness has already occurred. However, this dispute is not consequential to the use of depression angles. Even though depression angles relate directly to (the level of) darkness, since darkness levels and the appearance of stars occur approximately simultaneous, the argument is primarily of theoretical interest. As a result, the disagreement does not influence the use or the operation of depression angles.[1]

Second, a present disagreement is particularly consequential. Do we adopt fixed zemanim, e.g. 42 or 72 minutes after sunset or one hour before sunrise, or variable zemanim that change based both on location and day of the year? In Talmudic literature, physical events like the first appearance of light across the eastern sky, the ability to differentiate between blue and white, the sky’s apex and the eastern horizon appearing equally dark, the appearance of 3 medium stars, etc. all describe events whose occurrence vary at different locations and during different days of the year; they cannot be specified by a single fixed interval. As a result, I have a strong preference for variable versus fixed zemanim.[2] In spite of this being a still active dispute, I will assume that the argument is settled, and will not address the issue further in this paper. Clearly, depression angles are (largely) irrelevant to those who determine zemanim using fixed intervals. Therefore, this paper provides an explanation focused on depression angles themselves, as a methodology to formalize the use of variable zemanim. In what follows, I will explain the use of depression angles, the scientific method that has emerged over the last 150 years that makes use primarily[3] of both latitude and season / date to calculate various zemanim.

How this disagreement between using fixed versus variable zemanim developed would require its own detailed historical study, which I believe has not yet been attempted. Absent such a study, three factors appear to have had some bearing on the issue.

First, from the 12th through the 18th century, most observant Jews followed what is referred to as the opinion of Rabbeinu Tam, which equated the length of the intervals

- between sunset and the end of Shabbat and

- between alot hashaḥar and sunrise.

Because the length of the interval between sunset and the end of Shabbat was never lengthened, logic dictated that the (assumedly) equal interval between alot hashaḥar and sunrise be left invariant as well.[4]

Second, Pesaḥim 94a was (surprisingly)[5] read as implying that the time to walk a four milin interval applied year-round.

Third, in his forceful rejection of the opinion of Rabbeinu Tam, the Vilna Gaon proposed both seasonal and latitude-based variation with respect to both the intervals between sunset and the end of Shabbat and between alot hashaḥar and sunrise. While his view gained broad acceptance with respect to the end of Shabbat, its implications for variation based on both latitude and the time of the year with respect to alot hashaḥar, were (and still are) often ignored.

Without further attention to detailed halakhic issues, we will concentrate on the functional aspects of depression angles, (without requiring familiarity with spherical trigonometry on which they are formally based.) But first, we begin with a brief summary of some fundamental elements in the area of zemanim, which will help anchor the discussion.

Zemanim:

Two areas dominate the study of zemanim:

- First, how is the length of the 12 halakhic hours of every daytime period, which begins at alot hashaḥar, to be calculated given variation in the length of the daytime period during the different times of the year? Do we calculate from the daytime period’s halakhic beginning at alot hashaḥar or from the point of sunrise?

- Second, how do we determine the precise delimiters of a day of the week,[6] which almost all agree concludes approximately at the end of the of the bein ha-shemashot period in the evening?[7]

Avoiding the many disagreements in the halakhot of zemanim, we will assume without loss of generality that:

- The amount of time by which alot hashaḥar precedes sunrise, in the Middle East and around the spring and fall equinox when both the daytime and nighttime periods are equal, is 72 minutes.[8]

- The transition point between the days of the week and most critically, the end of Shabbat follows the opinion of the geonim (as opposed to Rabbeinu Tam.)[9]

Addressing primarily only alot hashaḥar and the end of Shabbat is sufficient to illustrate how depression angles can be used in halakha. In many communities, the methods used to determine the end of Shabbat versus alot hashaḥar are different and demonstrate concretely the issue that we will address. In those communities, alot hashaḥar is always a fixed 72 minutes before sunrise and the calculation of alot hashaḥar in those communities does not involve use of depression angles. On the other hand, the number of minutes after sunset at which 3 stars appear or a requisite level of darkness has been achieved varies considerably depending on where you are and the time of the year as well. As a result, very often the end of Shabbat is (either explicitly or implicitly) calculated using depression angles or a near equivalent.

Clocks:

Before addressing depression angles some background on the introduction of clocks into the halakhic literature is required. Beginning at the turn of the 16th century, about two centuries after the first introduction of mechanical clocks in Europe, clocks were first mentioned in the halakhic literature; at that time, knowledge of the impacts of latitude and season was still non-existent. Throughout the entire period of the rishonim, time intervals were typically referred to not by the number of minutes on a clock, but primarily as estimated intervals. Clocks added a mechanism that allowed various opinions previously specified in terms like the time required to do X, to be translated into a precise, easily specified interval of time.

Clocks began to proliferate almost 200 years before the first recorded reference to either the impacts of latitude or season appear in the halakhic literature. Those impacts were included by R. Avraham Pimential in his comprehensive sefer on zemanim, Minhat Kohen, written during the 17th century.[10]

The first mention of a clock in the halakhic literature was by R. Yosef ben Moshe, a student of R. Yisroel Isserlein, in Leket Yosher appearing around the turn of the 16th century;[11] it appeared more than a century earlier than Minhat Kohen. During the 14th through 16th century clock making accelerated, well before the nature of variances between zemanim at different locations and during different times of the year were appreciated.

Unfortunately, the precision that clocks provided may have resulted in their increased prominence at the expense of observation. Precision and accuracy are often confused. Clocks provide precision for measurements that may or may not be accurate halakhically. If someone tells you that Shabbat ends at a specific time, that assertion may be very precise but totally inaccurate. Clocks also provided a level of precision that may have been overly seductive. What is yet more disconcerting, clocks allowed pesak to be rendered independent of observation. With an assumed reduced reliance on observation, it is likely that critical halakhic definitions became more subject to disagreement. Examples abound in the halakhic literature:

- distinguishing between levels of darkness,

- differentiating between medium and small stars, or

- establishing the amount of illumination necessary to recognize a friend after dawn

are three clear examples. In each of those three cases, posekim’s opinions often varied significantly and/or recommended caution based on a level of acknowledged doubt.

In the 19th century, as personal timepieces proliferated and greater uniformity between clocks in different locations became necessary with the growth of the railroads, time took on a yet greater role, something we note but do not address further.

Variation by the time of the year and location/latitude:

In the entire period of the rishonim, instead of time-based measures, most mitzvot dependent on zemanim were performed based on the observation of natural events. The effects of latitude and the time of the year were incorporated implicitly by the use of observation. The occurrence of darkness or the appearance of stars varied naturally between locations regulated by a yet unknown science. How zemanim differed at different locations was largely immaterial; as far as I know, prior to the 17th century there is no discussion in the halakhic literature comparing zemanim at different locations.

After a significant interval where clocks proliferated, depression angles first appeared in the halakhic literature at the end of the 19th century. A depression angle[12] measures how far below the horizon the sun appears at a specific moment, providing an accurate measurement of the level of illumination; a larger angle indicates that the sun is further below the horizon with less discernable light coming from the sun. If a depression angle of X degrees occurs at 4:40AM in London and 5:10AM in New York on the same or different days, then one can be certain that the amount of light from the sun is the same at those two times.

If alot ha-shaḥar is defined by the degree of illumination from the sun, to determine alot ha-shaḥar across different latitudes and times of the year, one can[13] utilize depression angles. The first step is to establish the number of degrees below the horizon the sun is located 72 minutes before sunrise in the Middle East around the spring / fall equinox. The second step is to use that same number of degrees to determine alot ha-shaḥar elsewhere and during other times of the year. The 72-minute interval commonly accepted for alot ha-shaḥar corresponds to the sun being approximately 16 degrees below the horizon.

In Israel around the spring / fall equinox, scientists consider the sun to provide no measurable light until approximately 80 minutes before sunrise corresponding to a depression angle of approximately 18 degrees.[14] As the halakhah often disregards miniscule, non-visible quantities, this provides observational support for the standard pesak tacitly assumed that alot ha-shaḥar precedes sunrise by 72 minutes.

From everything I can determine, depression angles capture the halakhic notion of the degree of darkness and light accurately; no alternative for “measuring” ḥashekhah or alot ha-shaḥar has ever been formulated, nor has anyone ever proposed any problem that depression angles might create. Depression angles naturally adjust zemanim based on latitude and the time of the year. Clearly, we may not need such precision; observation was adequate for generations. Nonetheless, a depression angle is to darkness / illumination what a watch is to time.

A small depression angle corresponds to a significant amount of illumination coming from the sun even though the sun is below the horizon. After sunset the level of illumination decreases in a mirror image to the way the level of illumination increases as we approach sunrise. At a depression angle of around 5 – 6 degrees, the halakhic end of a day as specified in the Talmud occurs;[15] at a depression angle of around 11 – 12 degrees we arrive at the point of misheyakir. In between, at a depression angle of 8.5 degrees, Shabbat, as typically practiced currently, concludes. Translating a zeman into a depression angle is neither always straightforward nor undisputed. For certain zemanim, alot hashaḥar for example, the basis is clear: the level of illumination at the beginning of the daytime period, in the Middle East around the spring or fall equinox corresponding to an average time to walk 4 milim. To determine the transition point between days of the week and the end of Shabbat according to the geonim, both biblically and in practice incorporating various ḥumrot, is more complex. Fortunately, following R. Yeḥial Miḥal Tukatzinsky’s calendar for Jerusalem, the practiced end of Shabbat is almost universally accepted by those who rely on depression angles to equate to an angle of 8.5 degrees. Very few posekim following the geonim are more stringent; the practice of the overwhelming majority of 19th century posekim for whom we have calendars (from which depression angle equivalents can be inferred) were more lenient. However, the earlier point of ḥashekha or 3 medium stars, absent any ḥumrot, is still disputed.[16]

Given the earth’s circular shape, tilt, and rotation, computing depression angles involves spherical trigonometry, which is fortunately not needed for purposes of this paper. Similarly, albeit without the precision, Ḥazal used terms like mi-she-yakkir, hikhsif ha-elyon, the appearance of small/medium stars, etc. all of which relate to the degree of darkness or equivalently the amount of residual illumination from the sun. As noted in the introduction, there is a long-standing halakhic dispute pitting the primacy of darkness against the appearance of stars; which is defining, and which is just a useful indicator? I am strongly biased in the direction of darkness as defining; darkness was already recognized as causing the visibility of stars in geonic times. Since the level of darkness and the appearance of stars are strongly correlated, the dispute, as noted in the introduction, is not consequential to this short paper.[17]

Latitude, the time of the year and depression angles:

For any halakhik zeman, besides the level of darkness specified by a depression angle by which it is defined, two additional variables – the location’s latitude and the date of the year – must also be provided to calculate the time at which that halakhik zeman occurs. The intuition is important. To determine the time (after sunset or before sunrise) at which a level of darkness is achieved, we must know

- where you are, defined only by your distance from the equator,

- where the sun is, which can be calculated knowing the exact time of the year, and

- the level of darkness required.

The former two inputs are just unarguable facts; the latter requires a halakhic determination.

Those mathematically inclined, should think of this as a function of three variables: 1) latitude, 2) date, and 3) darkness level, where those inputs generate a number, the value of the function. That number equals the length of time before or after sunrise or sunset, respectively, at that latitude, on that day, when the degree of illumination expressed by that depression angle is achieved.

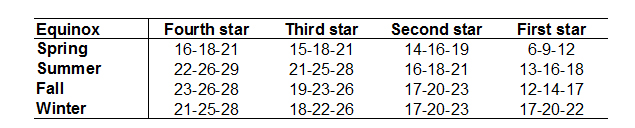

Both the latitude and the date play a critical role. However, until latitudes exceed 40 degrees, the seasonal variation for alot hashaḥar is less than about 20 minutes. For ease of explanation, the impact of the date, i.e. the seasonal variation, will be covered separately in the next section. To better understand the impact of latitude, the following discussion focuses on an arbitrary but specific day. The critical inputs in addition to that one day selected are 1) the latitude of the location and 3) the desired level of darkness, specified by a depression angle. I can input, for example, 1) latitude: 30 degrees and 3) the degree of darkness associated with a depression angle of 10 degrees.

For that specific day, given the latitude and a specified depression angle, the function calculates how many minutes before sunrise or after sunset the degree of darkness associated with that depression angle is achieved.[18] If you go further away from the equator, getting dark takes longer. What takes 42 minutes in Jerusalem takes approximately 50 minutes in New York. But things are a bit harder. Mathematicians will describe the result as non-linear, something that equates to “it is not simple.” For a depression angle of 8.5 degrees, it takes 8 minutes longer to reach that level of darkness in New York, situated about 9 degrees further from the equator than Jerusalem. If things were simple, i.e. linear, you might guess that it takes about 8 minutes more for every 9 degrees further from the equator that you are located. If you go 18 degrees further north of Jerusalem, you might expect having to wait (only) another 8 minutes, 16 minutes longer after sunset than the time it took to reach that level of darkness in Jerusalem. However, when we go 18 degrees further north of Jerusalem to Prague, an equivalent level of darkness is achieved 26, and not (a linear) 16 minutes, later.

Prague is further south than the locations of most European Jews who lived in Poland and Russia, about 48 to 56 degrees north latitude where change based on latitude accelerated. Additionally, depression angles have a second complicating factor. Instead of varying latitude, let us hold latitude fixed at say 50 degrees, the latitude again of Prague. Compare, for example, the number of minutes after sunset that it takes to reach a depression angle of 8.5 versus 16 degrees, the latter number being less than twice the former. On a day in early May those times for Prague are 58 and 130 minutes respectively, the latter being more than twice the former; a second non-linearity.

As both latitudes and desired level of darkness change, either very careful observation or scientific knowledge is required. It is not all that surprising that such precision was not always exhibited in the halakhic literature. Note that at latitudes further from the equator and at greater levels of darkness, the degree of seasonal variation increases as well, as we will see in the next section.

Dealing with seasonality

Posekim deal appropriately with seasonality in one of two fundamentally different ways:

- Some use a simple upper bound for a zeman where use of a such a number does not create significant inconvenience. Some treat R. Moshe Feinstein’s 50-minute zeman for the conclusion of Shabbat in the New York area that way.

- Alternatively, a posek can use depression angles; R. Yisroel Belsky adjusted R. Feinstein’s 50-minute zeman using depression angles to vary the conclusion of Shabbat between 40 and 50 minutes after sunset during different times of the year.[19]

To begin with, it is important to recognize that the magnitude of seasonal variation increases (non-linearly) both for:

- Locations further from the equator (thus greater variation in Montreal than Miami.)

- Greater degrees of darkness (thus greater variation in misheyakir than in the end of Shabbat.) (The average depression angle for misheyakir is approximately 3 degrees greater than the currently prevalent depression angle used to compute the end-time for Shabbat.)

For example, the seasonal variation for the end of Shabbat in Jerusalem is only 6 minutes, from about 36 minutes after sunset near the spring or fall equinox to about 42 minutes after sunset near the summer solstice. On the other hand, the variation in alot hashaḥar in Lithuania is “infinite.” Alot hashaḥar is 102 minutes before sunrise at the spring equinox, 120 minutes before sunrise at the winter solstice, and set to halakhic midnight during periods of the summer. In periods during the summer, the requisite level of darkness equating to a depression angle of 16 degrees does not occur; it never gets that dark during the night, something the Gaon observed.[20] Said differently, illumination from the sun never diminishes to that level either in the evening or equivalently in the morning. The extent to which this was neither recognized by posekim prior to the Gaon nor followed even after the times of the Gaon would require its own (lengthy) essay to illustrate.

The impact on the point of misheyakir provides another interesting topic for study. Pesakim from the Middle East tend to have an earlier point of misheyakir, often equating to a depression angle of between 13 and 11.5 degrees; pesakim from European posekim tend to use 11.5 degrees or less.[21] It suffices to say, posekim from northern Europe need to be read with care in discussions of this issue. Their views on alot hashaḥar and misheyakir are obviously linked; a delayed point of alot hashaḥar would likely delay the point of misheyakir as well.

Those following the 72-minute approach of Rabbeinu Tam should behave equivalently with respect to the end of Shabbat and alot hashaḥar, a practice rarely observed. It is alleged that R. Chaim of Brisk made havdalah Sunday morning, recognizing that Shabbat ends at (halakhic) midnight, coincident with alot hashaḥar and after the time he had already gone to bed. Such practice was rare. Interestingly, in Vilna, using a depression angle of 8.5 degrees to compute the end of Shabbat, a prevalent practice today, even the approach of the Gaon requires waiting 95 minutes after sunset to end Shabbat during the weeks around the summer solstice.

Unfortunately, many incorrect alternatives remain prevalent. Depression angles confirm that the shortest intervals occur in the spring or fall close to either equinox. The longest intervals occur around the summer solstice. Surprisingly to many, the interval around the winter solstice is longer than the interval in the spring or fall, but shorter than the interval in the summer. Because this was not properly understood, an error, going back to R. Pimential[22] persists until today.

While acknowledging that intervals vary by the time of year, in place of depression angles the error links variation in the interval with variation in the length of the period between sunrise and sunset. With this mistaken approach the summer interval is lengthened as it should be, but the variation is calculated imprecisely. In the winter the interval is shortened as opposed to lengthened, a very consequential error.

Interestingly and for reasons I can only suspect, posekim advised against using the implied wintertime reduction in time when it creates a leniency; perhaps the observed result did not conform to expectations or, as some might suggest, their counsel is another example of siyattah di-Shemayah.

A large and well entrenched group chooses not to make any seasonal adjustment. If done to promote simplification, as noted, that is a reasonable approach where implemented with care, (particularly for the end-time for days of the week at latitudes under 45 degrees.)

Often the implementation is entirely indefensible (most often for alot hashaḥar,) very often in combination with an equally poor approach to latitude, and often challenged by careful) observation. The clearest and most prevalent example is given by those who insist that alot hashaḥar is always 72 minutes before sunrise. Using this approach, one can easily end up with misheyakir visibly occurring before alot hashaḥar, a halakhic absurdity of the first order.

Conclusions:

The use of depression angles allows the determination of various zemanim without the need for observation. Given that the observation of various zemanim has become less widely understood and potentionally subject as well to various human frailties, it is likely that depression angles should become (yet more) widely accepted.[23]

[1]

In fact, on some calendars that clearly use depression angles to determine various zemanim, to avoid controversy the time given is stated in terms of the appearance of stars.

[2] A defense of fixed intervals practiced by a considerable number of posekim is provided by Rabbi Yisroel Reisman in his lecture (available on CD) “A Dawn’s Early Light, October 13, 2007.

[3] Other factors like elevation, temperature, humidity level, etc. have relatively minor impact and are not addressed. The halakhic significance of elevation is widely disputed.

[4] To the contrary, in the 17th century, R. Avraham Pimential, in the 19th century both R. Yaacov Loberbaum and R. Moshe Sofer and R. Moshe Feinstein in the 20th century reduced Rabbeinu Tam’s interval between sunset and the end of Shabbat to approximately 50 minutes, a complex topic not pursued further.

[5] This is rather ironic given that many rishonim remarked that the 12-hour day assumed by the gemara occurs only around the spring and fall equinox.

[6] Ironically, in both Hebrew and English, the words yom and day denote both the daytime period and the day of the week.

[7] According to the vast majority of rishonim, the day ends when bein ha-shemashot ends or at most 2 minutes later.

[8] 90 and on rare occasions 120 minutes are two alternatives to 72 minutes.

[9] As is often practiced in the New York area, it is approximately 45 versus 72 minutes after sunset.

[10] R. Pimential was acknowledged as an expert in zemanim by R. Avraham Gombiner, the author of Magen Avraham. Minḥat Kohen was carefully organized and argued; unfortunately, including two significant errors, which haunt us to this very day. Given his halakhic mastery and his unique role in introducing the important notions of latitude and season, his errors are inconsequential compared to his brilliantly organized analysis. In an odd but regrettable way, the persistence of his errors is testament to his monumental impact.

[11] Attempts to understand the use of a clock in those centuries is complex; unlike current clocks, many had astronomical significance linking clock time and real events like sunset, dusk, or midday.

[12] Depression angles were first discussed by R. Dovid Tzvi Hoffman; they were prominently used and advocated by R. Yechial Michel Tukitzinsky. Depression angles were popularized by R. Tukitzinsky in his work Bein HaShemashot and by Prof. Leo Levi in his book Halakhic Times (Jerusalem, 1967). In recent times, most online internet sites that provide zemanim (as well as many printed calendars) use this methodology extensively, albeit disguised on occasion. Among contemporaries, many posekim including R. Belsky and R. Willig and most seforim on zemanim use depression angles extensively.

[13] Even before one reaches the Arctic and Antarctic circles, particularly as one moves more than 60 degrees from the equator, many halakhot must be carefully examined.

[14] There is an interesting comment by R. Hoffman, Melamaid Le-hoil 30, like that of R. Pimential, relating the comment of R. Yehudah that oveyo shel rakiya are 1/10th of the day to 18 degrees being 1/10th of the 180-degree daytime movement of the sun.

[15] That point is relevant according to many posekim to determine the time at which to terminate a rabbinic fast.

[16] Remember that we benefit from a significant amount of artificial illumination at night, something that grew at various rates in many places. In areas where artificial illumination is entirely absent, the above depression angles will appear more reasonable.

[17] In my mind, the following represent the strongest arguments in favor of darkness:

- Early tannaic literature speaks almost exclusively of darkness.

- Darkness causes the appearance of stars that are present but not visible during the daytime period.

- The sugyah about Teveryah and Tzipporri (Shabbat 117a) strongly implies darkness as defining. (I found a visit to Tzipporri extremely helpful in understanding why the sugyah did not choose an elevated location closer than Tzipporri, over thirty miles from Teveryah.)

One side benefit of relying on darkness is that unlike counting the number of stars, measuring the darkness of the eastern horizon versus the top of the sky is less subject to light pollution.

Nonetheless, absent light pollution, by about 30 minutes after sunset in Israel there is little practical difference. Given the larger number of posekim promoting stars as defining, including the Gaon of Vilna, it is hard to be obstinate in maintaining an unrestrained bias for darkness as defining.

[18] With respect to depression angles one will often hear / read the sun appears, as opposed to is, X degrees below the horizon to incorporate accurately the critical importance of the position, i.e. latitude, of the observer. An observer at different latitudes will perceive the sun differently based on both 1) their distance from the equator and 2) whether they and the sun on the same or opposite sides of the equator.

[19] This is strongly implied in his approbation for the website www.myzemanim.com.

[20] See the Gaon’s lengthy comment on O.H. 459.

[21] See the various pesakim quoted in R. Benish, HaZemanim BeHalakha chapter 23.

[22] Without a wintertime observation R. Pimentel (incorrectly) assumed the period was 1/15th of the daytime (sunrise to sunset) period assuming a linear relationship that conformed to his two points of observation at the spring equinox and summer solstice.

[23] This paper is meant to explain the use of depression angles; even for those who completely follow what was presented, halakhic conclusions can be drawn only at the reader’s peril.