Using a Colophon to Find a Shidduch: on Ella the Zetser.

by Eli Genauer

There has been much talk lately about the so called Shidduch crisis. Various initiatives have been proposed to address this problem, all of which are well meaning and well thought out. Many might be surprised to learn that an interesting approach was suggested by a 12 year old girl in the town of Frankfurt on Oder way back in 1699. This approach was based on a Pasuk in Yirmiyahu which deals with Messianic times.

We are all familiar with the 31st chapter of Yirmayahu. The first 19 pesukim of this Perek comprise the Haftorah of the second day of Rosh Hashana. The Navi begins, “Koh Amar Hashem, Matzah Chain BaMidbar”. The Haftorah proceeds to lay out a vision of Hashem’s love for the Jewish people and its eventual return to Tziyon, a fitting theme for a day in which we ask Hashem to grant us a good year. The stirring Pasuk of “HaVain Yakir Li Ephraim” concludes the Haftorah, but the Perek continues with Yirmiyahu’s vision of Yemos HaMoshiach.Yirmiyahu speaks of the Jewish people in Galus and after having been there for so long, they return to Hashem. Pasuk 21 states the following:

כא עַד-מָתַי תִּתְחַמָּקִין, הַבַּת הַשּׁוֹבֵבָה: כִּי-בָרָא יְהוָה חֲדָשָׁה בָּאָרֶץ, נְקֵבָה תְּסוֹבֵב גָּבֶרHow long will you hide, O backsliding daughter? For the Lord has created something new on the earth, a woman shall go after a man.

According to the Radak, the Navi is imploring the people to travel on a straight path and to return to Hashem. This will be a time when, as it were, the Bas HaShoveiva, the backsliding daughter, will be the one who seeks out a husband, in this case Hashem. The Navi says that this is something that is radical, but certainly required at that time.

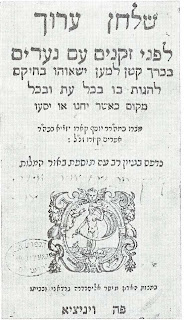

We fast forward a bit to 1696 and we meet an amazing nine year old girl, born in Amsterdam, but now living in Dessau, Germany. Her name is Elle and she is the daughter of a man named Moshe ben Avraham Avinu. Moshe worked for years setting type and printing important Jewish books in various places in northern Europe, the last of which he did under very trying circumstances in Halle.(1) Moshe employed his children to help him in the arduous task of typesetting. We know a bit about his daughter Elle from some crumbs that she left us as she signed her name to the books she helped bring to print. She and her brother worked on setting type of the Siddur Drash Moshe printed in Dessau in 1696. After recording that the book was set to type by Yisroel ben Moshe, someone wrote a poem which tells us that a nine year old girl named Elle (עלה) helped Yisroel in this project: (This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library)

(This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library)

The Yiddish letters I set with my own hand

I am Elle, the daughter of Moses from Holland

a mere nine years old

the sole girl among six children

So when an error you should find

Remember, this was set by one who is but a child (2)

Did she compose the poem herself, or was it composed by her father or brother? Remarkably, we find another case not soon thereafter, of a nine year old setting type, and there we do know whether he could read or not. Nicholas Basbanes, in his book “A Gentle Madness”, records the following:

“Born in poverty, Isaiah Thomas came to know the touch and smell of ink on paper when he was only a child. Only nine years old in 1758….young Thomas was already completing his apprenticeship in the dingy Boston shop of Zechariah Fowle…When he later became the most successful printer and publisher in the United States-Benjamin Franklin dubbed him the Baskerville of America- Isaiah Thomas enjoyed telling friends that he knew how to set type before he was able to read.”(3)

Whether or not she could read at age nine, we do know that this little girl was able to recognize the Judeo Yiddish letters of a manuscript and set to type similar letters from which to print a book. Perhaps she had the potential to become as successful as Isaiah Thomas but for her gender and religion.

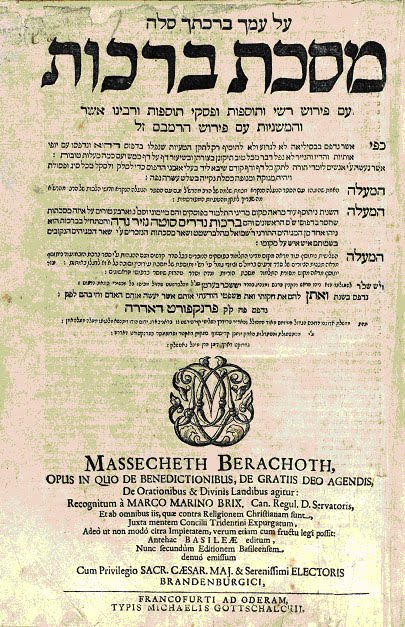

We meet Elle again in 1699, this time as a typesetter working on the famous Berman Shas of Frankfurt on Oder. This printed edition of the Talmud ( 1697-1699) was financed by the wealthy court Jew, Yissachar Berman Segal of Halberstadt who gave away half the 5,000 copies printed to needy scholars throughout Europe.(4) The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague:

The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague: At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.

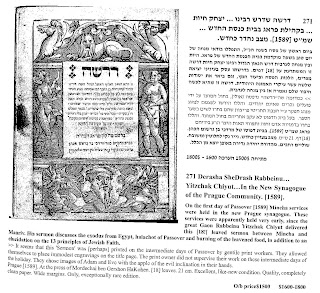

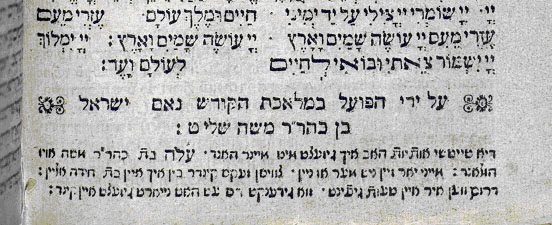

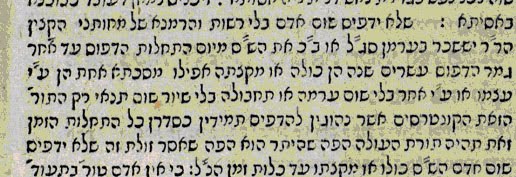

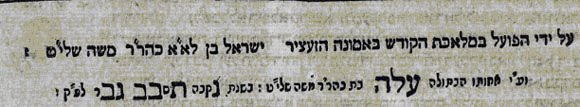

At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.

“ By the hand of the faithful typesetter in this holy work, Yisroel the son of Reb Moshe. And by the hand of his maiden sister Elle, daughter of Rav Moshe, in the year “N’Kaivah T’Soivev Gaver” ( “a woman shall go after a man”.)

When you add up the letters which are set in large type, you come up with the year 459 according to the Peret Koton ( the abbreviated era ). This is the year 5459 (1699). What intrigues even the casual observer is why she, or her older brother Yisroel chose to record the year 5459 using that unusual Pasuk? One could argue that the Pasuk is tangentially related to some of the topics covered in Maseches Niddah, but there are many other Pesukim which deal more directly with the subject matter that could have been formatted to equal 459.(7) I think it is more logical to relate the Pasuk to the girl typesetter, who we are informed, is still unmarried. In Messianic times, it will be the Kallah, Am Yisroel, who seeks out its Chasan, Hashem. Perhaps Elle thought her circumstances and position necessitated a similar approach to finding a suitable Chasan. We hear the last from her in the next year having worked on a Machzor with her brother Yisroel.(8) We hope that after that, this extraordinary girl found an appropriate Shidduch. We wish the same for all those seeking the wonderful rewards that marriage has to offer.

(1) Marvin J Heller, “Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book”, Boston 2008 pps. 218-228. The entire chapter on Moses ben Avraham Avinu makes for some fascinating reading. I am indebted, as are we all, to Marvin Heller for his research into this field of study.

(2) Ibid: p.222

(3) Nicholas Basbanes, ‘A Gentle Madness” New York, 1995 pps144-145

(4) R.N.N. Rabinowitz “Ma’amar Al Hadfasas HaTalmud”, A.M. Haberman edition, Mosad HaRav Kook 2006, page 96 footnote 1.

(5) Ibid. p. 98

(6) Ibid p.100

(7) Two examples of a more fitting Pasuk to denote the year of publication for Tractate Niddah are:

“B’Mai Nidah Yischatah” which was used in Frankfurt A/M edition of 1720, and

“V’Safrah Lah Shiva Yomim, V’Achar Ti’Taher” which was used in the Dyhernfurth edition of 1816-21 ( although the highlighted letters actually add up to (5)773)

(8) Heller, page 223