Towards a Bibliography About Realia and Chumash, specifically relating to the Mishkan and Bigdei Kehunah

Learning Chumash and Nach is extremely important for many reasons. Over time it became a neglected subject (why is the subject of a different post IY”H) and in many circles is still true today. Sadly, many people remain with the images of the various stories from Tanach the way they heard it in their youth without a genuine understanding of the events. I strongly believe that learning Tanach properly (by both students in school and adults) could help with some of the issues we face today. In recent years there have been attempts to fix this problem but there is still much work to be done.[1] There are many works out there to help one deepen their understanding of Tanach, each focusing on different aspects.

In this post I will limit myself to mentioning some of the recent, general works on the topic that I feel can help. However, the main focus of the post will be a listing and description of works to help one learn Parshiyos Terumah through Pekudei, with emphasis on works that focus on the Realia. I will also quote some general sources of the significance of understanding the Realia. Eventually I will return to add more works and Parshiyos to this list. I will also deal with other aspects of learning Tanach. Just to mention one area to help one understand Chumash which I dealt with a bit in the past – that is Via learning Targum Onkelos properly, see

here and

here.

אמנון בזה, עד היום הזה, שאלות יסוד בלימוד תנ”ך, ידיעות ספרים, 470 עמודים.

היא שיחתי, על דרך לימוד התנ”ך, בעריכת ר’ יהושע רייס, מכללת הרצוג תשע”ג, 264 עמודים

בעיני אלוהים ואדם, האדם המאמין ומחקר המקרא, בעריכת יהודה ברנדס, טובה גנזל חיותה דויטש, בית מורשה ירושלים תשע”ה, 487 עמודים

Moshe Sokolow, Tanakh, An Owner’s Manual, Authorship, Canonization, Masoretic Text, Exegesis, Modern Scholarship and Pedagogy, Urim 2015, 219 pp.

David Stern, The Jewish Bible, A Material History, Washington Press 2017, 303 pp. [Beautifully produced]

Yitzchak Etshalom, Between the lines of the Bible, Genesis, Recapturing the Full meaning of the Biblical Text (revised and Expanded), Urim/OU Press, NY 2015, 271 pp.

Yitzchak Etshalom,

Between the lines of the Bible: Exodus: A study from the new school of Orthodox Torah Commentary, Urim/OU Press, NY 2012, 220 pp. [On this work see

here]

See also the incredible site

ALHatorah.org which is extremely useful.

Also, worth mentioning is the new series which I am enjoying so far:

יואל בן נון, שאול ברוכי, מקראות עיון, רב תחומי בתורה, יתרו, 278 עמודים

יואל בן נון, שאול ברוכי, מקראות עיון, רב תחומי בתורה, 608 עמודים

See their Website for more information

here.

Many years ago, when I was in fourth Grade, my Rebbe, Rabbi Zacks (who loved seforim) taught us the Parshiyos of Terumah etc. While learning it he would take out this fancy and expensive book with color pictures of the various Kelim in the Mishkan and of the Bigdei Kehunah to help us better understand what we were learning. He was using visual aids of pictures to help the students understand Chumash. I recall that when it was Friday of Parshas Terumah there was non-stop knocking on the classroom door, because Rabbeyim from different classes sent students to borrow the sefer so that they too could show their classes the pictures while learning Parshas Hashavuah. A few years later I recall someone bringing and setting up a real model of the Mishkan and Kelim to our school. All this helped us understand the Chumash a bit better.

A few years ago I heard a shiur in Jerusalem from the prolific Rabbi Yechiel Stern on Visual aids for learning, as he had written many such seforim to help students. He described that at first there was much opposition to what he was doing but eventually it became more and more accepted.

At the time I realized that this was something that the academic world was busy with for well over hundred years and wrote on this numerous works. However, that obviously would not help the case to get mainstream Yeshivos to use these works even when the authors were frum and the like. (See further on).

However, the truth is that there were many Gedolim who had realized the significance of using Visual aids while teaching and of understanding the Realia while learning Chumash.

Just to list some sources.

R’ Sofer writes about the Chasam Sofer:

לתכלית גדול הזה לברר הלכה לאמיתו ולהעמיד כל ענין על בוריו הי’ לו לכל שיעורי תורה כלים מיוחדים מדודים מאתו בדקדוק הדק היטב להראות לתלמידיו וכן הי’ לו בארגז מיוחד שני צורות תבנית זכר ונקבה מעשה אומן מופלא והיו נעשים פרקים פרקים וכל חלקי הפנימים מעשה חדש נפלא ללמוד וללמד חכמת הניתוח ולא הראה זה רק לתלמידים מובהקים אשר יראת ה’ אוצרם בעת למדו אתם הלכות נדה וכדומה.[2]

Regarding the Minsker Godol after he got his first position, he sat with the head Dayan to see exactly how to Pasken. His reason for this was:

“מעולם לא ראיתי הדברים האלה במציאות, וכל ידיעותי אינן רק מהעיון והלימוד בספרים…”.[3]

In a Haskamah of the Aderet he writes as follows:

בואו ונחזיק טובה להרב המובהק הנ’… אשר המציא להשכיל להטיב לצעירי התלמידים להקל מעליהם למוד ההוראות במקצוע הל’ שחיטה וטריפות בהמציאו ציורים ותמונת מכל אבר ואבר לכל פרטי מוצאיו ומובאיו על פי מקורים נאמנים… התענגתי מאד לראות חיבורו סי’ אהל יוסף נחמד למראה וטוב למעשה לא לבד לצעירי התלמידים אשר לא ראו ניתוח בעלי חיים מעודם, כי אם גם למוריהם, כי יקל הלימוד לתלמידיהם להורותם הלכה למעשה על כל פרט ופרט לאמר בזה ראה וקדש”.[4]

In the extremely interesting autobiography of Eliezer Friedman he writes:

מצאתי אצל אחד… ספר רבני ובו לוח

הריאה וציורים. אנכי הייתי אז בקיא מאוד ביורה דעה. ראיתי כי באמת נחוץ לחניכי הרבנים לומדי היו”ד, לוח הריאה אבל לא כזה שמצאתי שאינו אומר כלום… צירתי עלי גליון גדול, צורת הריאה, אונותיה ואומותיה וכל סוגי השאלות אשר אפשר להוליד בהלכות ריאה. הכל מצויר בצבעים שונים, צבעים טבעיים כפי הלקוי והמחלה אשר ידובר עליהן בש”ס ופוסקים. על כל לקוי, הצגתי אות מספרי ובצד הציור כתבתי בקצור נמרץ שם הלקוי, תמצית דעות הפוסקים והחלט הדין להטריף או להכשיר, את הציור אזה הראיתי לגאונים ר’ נפתלי צבי יהודה מוולואזין ור’ שלמה הכהן מווילנא. הם סמכו ידעם על הציור להשתמש בו הלכה למעשה, ואמכור אותו למדפיסים ראם בווילנה. גם סמיכה להורות ולדון נתנו לי (ספר הזכרונות, עמ’ 136).

See also the important introduction related to this in Rabbi Moshe Leib Shachor, Bigdei Kehuna (pp.10-11).

Turning to these Parshos in Chumash in Particular.

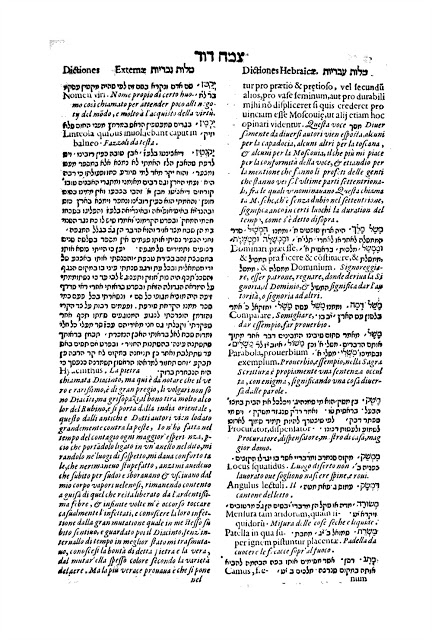

In 1612, R’ Abraham Portaleone (1542-1612), a Talmid Chochom and medical doctor, printed in Mantua his encyclopedic masterpiece Shiltay HaGiborim. This work deals in great depth with every aspect of the Mishkan and Mikdash, with a tremendous focus on Realia. For example, when dealing with the Kitores, he methodologically investigates every aspect of it (pages upon pages) drawing upon his expert knowledge in sciences and command of ten languages. Similarly, when discussing the stones of the Choshen, he tries to identify the stones, using these same tools, while covering other aspects related to them. When dealing with the music and the instruments used in the Beis Hamikdosh, he again devotes many pages to the subject, explaining it via knowledge of the Realia. This last section on Music was the Subject of a PhD dissertation in 1980 written in Tel Aviv by Daniel Sandler.

In a lecture about this work, Prof. Zohar Amar said as follows (one can see it

here or read it

here):

רבנו אברהם הצליח להקיף ולהתמודד בחיבורו עם נושאים שונים ומגוונים הקשורים למקדש, כמו תוכנית מבנה המקדש וכליו, הקרבנות הראויים לעלות למזבח, בגדי כהונה, אבני החושן, סממני הקטורת, עצי המערכה, תפקידי הלויים, ובהם שירה וזימרה, שמירה, וכן סדר התפילות והקריאה בתורה ועוד נושאים רבים. בכל אחד מהנושאים שעסק, הוא הפגין ידע ובקיאות מעוררת השתאות, בתחומי הזואולוגיה, הבוטניקה, מנרולוגיה, מוסיקה, רפואה, טכנולוגיה ועוד ועוד. בעצם לפנינו חיבור אנציקלופדי רחב היקף, האנציקלופדיה הראשונה שנכתבה על המקדש.

אז מה הופך את רבנו לחוקר ? ראשית, רבנו אברהם היה בעל ידע נרחב בכל הספרות היהודית לדורותיה, ובהקדמתו הוא מנה כמאה מקורות בהם השתמש, החל מספרות חז”ל, הגאונים, הראשונים וחכמים בני תקופתו. אולם מקורות הידע שלו לא הצטמצמו לארון הספרים היהודי, אלא הוא היה בקיא גם בכל מכמניה של הספרות הקלאסית, היוונית, הרומית והערבית, וספרות המדע שהתפתחה בתקופתו. רבנו אברהם ניחן באחד מכלי המחקר החשובים ביותר והיא ידיעת שפות. על פי עדותו בהקדמה הוא השתמש בחיבורו בעשר שפות: איטלקית, ארמית, גרמנית, צ’יכית, יוונית, לטינית, ספרדית, ערבית, פרסית וצרפתית.

In 2010 Mechon Yerushalyim and Mechon Shlomo Uman put out a beautiful, annotated edition of this special work (47+709 pp). At the end of the thorough introduction they are very open and quote Prof. Amar as follows:

אולם פרופ’ זהר עמר העיר בצדק שלצורך הוצאת מהדורה מדעית מלאה של הספר נדרשת עוד עבודה רבה מאוד. מדובר בספר מסובך עם מאות רבות של מונחים בשפות לועזיות שונות, והוא דורש התמודדת עם הספרות הקלאסית היוונית והלטינית (כמו אריסטו, תיאופרסטוס, פליניוס, דיוסקורידס וסטארבו) מחד, וספרות ימיו של רבנו המחבר (כמו חיבוריהם של פרוספר אלפין ואחרים) מאידך, ויש צורך להשוות את כל הציטוטים עם המקורות עצמם על רקע העובדה שהמחבר הוא הראשון שמביא את תרגומם בעברית. מעבר לכך חייבים לזהות באופן שיטתי את כל הצמחים, בעלי החיים והמינרלים שבספר, ולהתחקות אחרי תהליכי ייצור וטכנולוגיה המוזכרים בו (למשל ייצור סבון). כל זה דורש מחקרים נוספים בעזרת מומחים לתחומים השונים, והרבה הרבה זמן (יתכן שכדאי יהיה להוציא בעתיד נספח מדעי למהדורה זו.

Although what Amar writes is very true, what they did do is extremely useful.

Just to add one more source about R’ Abraham Portaleone: See the two excellent chapters devoted to him by Andrew D. Berns, in his recent book The Bible and Natural Philosophy in Renaissance Italy, Cambridge 2015, pp. 153-230. One chapter focuses on his correspondence with his Gentile colleagues found in an unpublished manuscript of his. The other chapter deals with R’ Abraham Portaleone’s sections devoted to the Kitores.

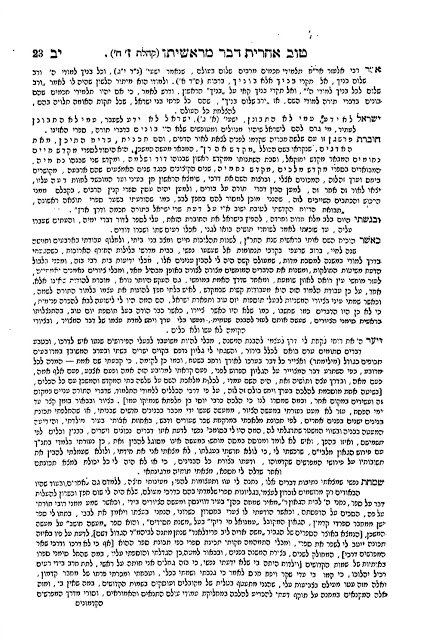

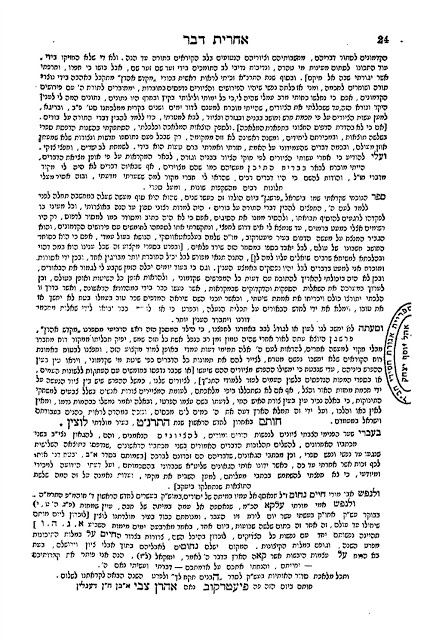

Over the centuries other works were written devoted to explaining the Realia of the Mishkan and Mikdash (hopefully one day I will compile a detailed list). In 1891 a work called

Mikdash Aron was printed’ a bit later the same author printed another work also devoted to this subject called

Parshegen.

Rav Kasher writes about this work as follows:

וראיתי להעיר כאן על ספר זה, שמוקדש לביאור מעשה המשכן וכל כליו, הלוחות וספר תורה ולחם הפנים. המחבר עשה מלאכה גדולה, שערך הכל בקצור נמרץ והכניס הרבה, חומר על כל אלה ,ענינים בעשרים דפים (40 עמוד) ונראה, מתוך ספרו שהשקיע בו הרבה זמן ויגיעה גדולה. אמנם הסדר שלו הוא מוזר. מחבר זה סדר לו פנים וביאור. הפנים נכתב באופן סתמי ומוחלט שהקורא חושב שהוא מועתק מאיזה, מקור והביאור נותן המקורות, וכל מעיין משתומם לראות אין שבכל ענין וענין כותב לו בפנים דברים שהם השערות גרידא מהרהורי לבו שאין להם שום מקור ויסוד ,והרבה פעמים מציין מקורות אבל לא הבין הדברים כראוי, וכותב להיפך מהמבואר בראשונים כי דרכו הוא בלשון מדברת גדולות ולכן אין לסמוך על דבריו רק צריכים לבדוק המקורוות ותמה אני על א׳ מהגדולים המסכים על ספרו בהערות להוצאה שניה, מהספר מביא שכמה מהגדולים בזמנו פלפלו עמו וכנראה, שלא נפנו לקרוא בעיון בהספר, לכן לא העירו להמחבר על עיקר גישתו שאינה נכונה [תורה שלמה, כב, מילואים, עמ’ 23].

Rav Kasher writes he does not understand how one of the Gedolim who gave a Haskamah did not comment. This appears to be a strange story and requires further investigation of the various editions of the work. The author has various letters from Gedolim and brings various comments he received from them about the work. One of the Gedolim who he was in correspondence about his works was the Netziv. Interestingly, the Netziv writes in one of these letters:

תבנית הארון והלוחות כבר שלחתי להגרש”מ כמבוקשו…

[Some of the letters were reprinted in Igrot Netziv, pp. 39-41 but not all of them. I have no explanation for this].

Of interest is what the author writes describing how he came to writing this work and his meeting with R’ Meir Simcha

Besides for publishing works on the Mishkan others built models. R’ Tuviah Preshel collected a bunch of accounts of people who actually built such models of the Mishkan to help people understand it (See

Ma’amarei Tuvia, 1, pp. 412-419 available

here).

One work in particular which still has not been outdated is the Living Torah from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. Although his translation on the whole torah is very important, the sections on these Parshiyos are extremely special and useful.

Turning to specific “ingredients” we find mentioned in these parshiyos time and time again. There are a few works of Zohar Amar relevant, all of which investigate the particular topic from the early sources until recent developments. See for example:

זהר עמר, בעקבות תולעת השני הארץ ישראלית, תשס”ז, 106 עמודים

זהר עמר, ספר הקטורת, תל אביב תשס”ב, 197 עמודים

זהר עמר, הארגמן, פורפורה וארג’ואן במקורות ישראלועוד בירורים בענייני התכלת, תשע”ד, 281 עמודים

במסגרת המחקר פיצחתי כ-11000 קונכיות של ארגמונים לצורך מיצוי צבע מהם (עמ’ 13).

ר’ ישראל ראזענבערג, קונטרס מרכבו ארגמן, והוא בירור מהות צבע ארגמן מדברי חז”ל עד האחרונים וביאור המסורה בזה [וגם יתבאר בו מהות תולעת שני], נד עמודים.

I am specifically avoiding listing material on תכלת as there has been a recent explosion on the topic (especially of note are the booklets coming out of Lakewood). Someone needs to put out a proper bibliography of all the works on this hot topic. Just to mention three recent discussions related to the topic.

I, See Dovid Henshke’s recent article in Assif 5 (2018)

פתיל תכלת וגידלי ציצית בירורים בקיום מצות תכלת בציצית

ר’ יהושע ענבל, קוציו של ארגמון, האוצר יא (תשע”ח), עמ’ רעא-שיב.

A PDF is Available upon request.

Three Listen to

this Shiur – specifically the Part from Rabbi J. D. Bleich.

A special article devoted to literary all aspects of the Aron is from R’ Menachem Silber, published in Sefer HaZicron LeRebbe Moshe Lipshitz (1996), pp. 229- 272. The Article is titled ארון העדות ולוחות הברית: צורתם ותבניתם. The article is written very concise, in an encyclopedic style, includes hundreds of footnotes and is well worth ones time to go through.

An interesting point related to this article is in a publication of Encyclopedia Talmudit where they discuss various issues related to their publication:

ערך לוחות הברית, לאורך זמן רב פקפקנו אם יש לו מקום באנצ”ת. הנושא אינו הלכתי ממש, ניתן לראותו יותר כרקע להלכה, שיש להניחם בארון שבקדש הקדשים, ולדעת הרמב”ן יש מצוה מיוחדת לעשות ארון לצורך הלוחות, כגון אם נמצא אותם בלי ארון. אכן ענין זה כבר נידון כללית בערך ארון. והנה סמוך לסוף הכרך קבלנו מאחד מלומדי האנצ”ת עבודה יפה שהוא ערך בנושא, ובקשנו לראות אם היא מתאימה לנו. במבט ראשון אכן נראתה דומה לערך באנציקלופדיה, וכאן המקום להודות לו מקרב לב. זה עורר אותנו לשיקול מחדש, ובסופו של דבר הערך נכתב, ולמעשה השתנה מהמסד עד הטפחות, והלומד ימצא בו ריכוז של סוגיות שונות בתלמוד בבלי וירושלמי, סביב צורתם של הלוחות.

I assume they got a copy of Rabbi Silber’s article and this helped them change their minds. See the entry in Encyclopedia Talmudit, 37, pp. 143-150. In Footnote # 21 they quote the article (I think they should write out the authors name).

ר’ עזריאל לעמל כ”ץ, קונטרס מנוחת השכינה, מראי מקומות וביאורים בענין הארון, ביאור מקיף בענין מנוחת השכינה על הארון, נצחון ישראל, נגד האויבים ע”י נשיאת הארון למלחמה, ושמות של הקב”ה שהיו מונחים בארון, ועוד, תשע”ו, צח עמודים

For information about all aspects of the of Lechem Hapanim: See the excellent entry in one of the most recent volumes of Encyclopedia Talmudit, 37, pp. 483-591

About making of Lechem Hapanim see:

זהר עמר, חמשת מיני דגן, תשע”א, עמ’ 129-172

On the Menorah throughout the ages:

See Daniel Sperber, “The History of the Menorah”, Journal of Jewish Studies 16:3-4 (1965) pp. 135-59, and in his Minhaghei Yisroel, 5, pp. 171-204. Daniel Sperber in Daniel Sperber Articles, Reviews and Stories 1960-2010, Jerusalem 2010, p. 11.

See also the very interesting new work on the subject from Steven Fine,

The Menorah, From the Bible to Modern Israel, Harvard University Press 2016, 279 pp. [For a review on this work see

here]. Related to this and a recent display he arranged see

here.

Baraita De-Melekhet Ha-Mishkan

A much earlier “neglected” work important to use when learning these parshiyos is Baraita De-Melekhet Ha-Mishkan.

For Meir Ish Shalom’s edition see

here. R’ Chaim Kanievsky commentary on this work is available

here. A recent critical edition of this work was done by Robert Kirschner,

Baraita De-Melekhet Ha-Mishkan: A Critical Edition with Introduction and Translation, 1992, 320 pp. For a review of this edition see Chaim Milikowsky, “On Editing Rabbinic Texts: A Review-Essay of Baraita de-Melekhet ha-Mishkan: A Critical Edition with Introduction and Translation by R. Kirschner”,

JQR 86 (1996), pp. 409-417 (

here). For a recent commentary on this work see:

ר’ חיים דיס, דברים אחדים, אנטווערפען תשע”א, על ברייתא דמלאכת המשכן, בגדי כהונה ועוד, תקנו עמודים

This work is available free in PDF

here.

Two other random works I will mention here are:

רבינו שמעיה השושני, סוד מעשה המשכן, כ”י, [מדורו של רש”י], מהדיר: ר’ גור אריה הרציג, 2013, 20 עמודים.

יעקב שפיגל, לשון הזהב (חישוב הזהב הנדרש לכלי המשכן והמקדש) לר’ יצחק בן שלמה אלאחדב, בד”ד 12 (תשס”א), 5-34

An important work that had tremendous impact on many of those related to Wissenschaft as well as those who identified with the Haskalah movement was R’ Azariah de Rossi’s Meor Einayim. This work, first printed in Mantua in 1573, was really a few hundred years ahead of its time. However, for a long period of time it remained underaappreciated and, in some circles, even banned. De Rossi’s book was an attempt to deal with the chronological and intellectual history of Judaism during the Second Temple and early Rabbinic periods. The author devoted a considerable amount of space towards understanding Chazal and Aggadah. De Rossi employed critical methods, including philology, going back to translating early original documents from their source languages. Many of these methods eventually became the trademark of Wissenschaft.[5] Zunz wrote the first definitive study on the history and usage of this work, emphasizing its importance.[6] The work also influenced people affiliated with the “GRA school”, such as RaShaSh and Netziv (who quotes it in relation to the Bigdei Kehuna).[7] One lengthy section of this work is devoted to the Bigdei Kehuna (See his Imrei Bina, Ch. 46-50) where he has a lengthy discussion based on Rishonim and other sources such, as Yosifon and Philo. While I am not sure if R’ Abraham Portaleone in his Shiltei HaGiborim, also printed in Mantua a bit later, made use of the Meor Einayim‘s discussion, it’s worth mentioning that he also deals extensively with the Bigdei Kehuna.

One outstanding work on the topic of the Bigdei Kehuna is Rabbi Moshe Leib Shachor, Bigdei Kehunah (1971) 447 pp.

For a review on this book see Daniel Sperber, Daniel Sperber Articles, Reviews and Stories 1960-2010, Jerusalem 2010, p.51 who writes about it:

It is the work of a true Talmid Chacham with a tremendous Bekiyut… applying the traditional methods… to a relatively unexplored field… The depth and detail of treatment is sometimes most astounding… His sharpness and his critical abilities glimmer through the printed words… This book has a wealth of information on a little-known subject. It is clearly written, well organized….

An older work on Bigdei Kehunah is available

here. For a recent book on this subject see:

ר’ זאב לופיאן, לשרת בקודש, ירושלים תשע”ו, בעניני בגדי כהונה, תפו עמודים

ר’ ישראל גארדאן, קונטרס לב ישראל, בעניני האפוד והחושן, ללוס אנג’לס תשע”ג, 123 עמודים

זאב ספראי, משנת ארץ ישראל, יומא, עמ’ 249-269

The stones of the Choshen

Recently much has been written on the Stones of the Choshen.

.זהר עמר, החן שבאבן, אבני החושן ואבנים טובות בעולם הקדום, תשע”ז, 350 עמודים

See also the important article on the topic from Rabbi Yankelowitz:

זיהוי אבן החושן על פי תרגום השבעים והתרגומים הארמיים, חצי גיבורים י (תשע”ז), עמ’ תעח-תקמא.

A pdf is available upon request.

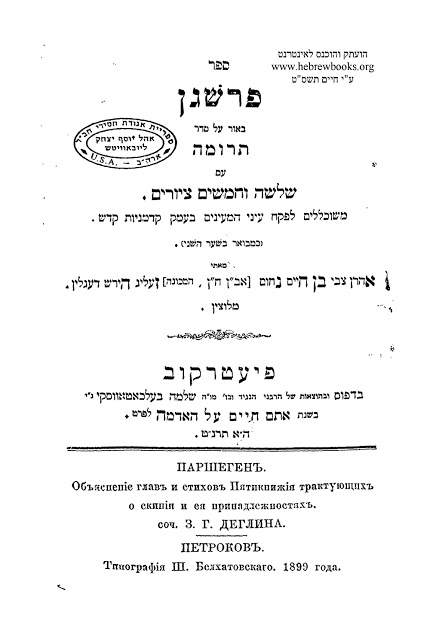

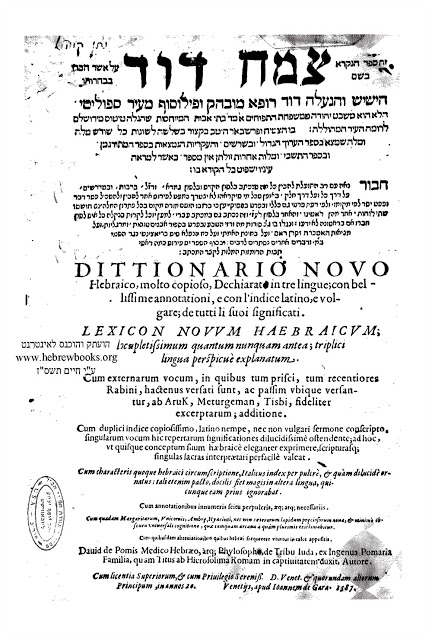

See also the chapter of Andrew D. Berns, in his recent book The Bible and Natural Philosophy in Renaissance Italy, Cambridge 2015, pp. 109-152, “The Grandeur of the Science of God” David De Pomi and the stones of the High Priests Breastplate. The Chapter is specifically devoted to understanding David De Pomi of the Tarshish stone in his Tzemach Dovid[8] where he identifies it as the diacinto and mentions the Segulos of this stone.

It appears that even though some will use visual aids and Realia for teaching Chumash, many are nervous about introducing Realia when learning Talmud. See

here,

here and

here for some recent discussions on the subject. [For Earlier posts related to this see

here and

here] Although I personally am not sure how one can say its not important or relevant (but I am biased and tainted from Academia already). I suspect that part of the issue is that the fear is at times the outcomes might clash with Halacha. This itself has many ramifications and is an explosive topic which I hope to return to someday.

To cite just one example, over ten years ago I wrote:

One of the greatest poskim of the past century, R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, was famous for how he consulted experts and tried to understand the exact facts before issuing a pesak. This is evident in all his writings on all of the modern-day issues. One example: In recent years there has been much written on the bottle cap opening of shabbat — it even has its own huge sefer (as virtually everything else does these days) on the topic! One of the rabbanim who has been involved with this topic for years is R. Moshe Yadler, author of Meor Hashabbat, where he has written on this topic and spent many hours speaking to many gedolim about it. When he was researching the topic he made sure to track down every type of bottle, he visited factories to see how bottles are made so that he would be able to understand exactly how it is made so he would be able to pasken properly. When he gives a shiur about this topic he comes with a bag full of all types of caps to demonstrate to the crowd the exact way it is made, etc. He told me once that he spoke to R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach about this many times. At one point he requested R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach to put in writing all his pesakim on the subject to which the latter did. R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach’s son told R. Yadler that his father sat for three days with a soda bottle in front of him the whole time he was writing the teshuvah and he kept on taking it on and off.

Yet elsewhere we find R’ Shlomo Zalman writes in regards to some of the discoveries of Yehudah Felix:

קיבלתי יקרת מכתבו מעולם לא אמרתי לשנות מהמסורת והשו”ע וכמו שאין שומעין לפרופ’ פליקס (שהוא שומר מצוות) ששבולת שועל הוא לא מה שקוראים העולם, ואין שומעין לו ומברכין מזונות, וכן הוכיח באותות שתמכי הנקרא חריין לא היה כלל בזמן חז”ל ואין יוצאין בזה מרור, ואעפ”כ אין שומעין לו נגד המסורות. וכ”ש בענין זה שמפורש בשו”ע וכידוע (ר’ צבי גולדברג, מסורתנו, ירושלים תשס”ג, עמ’ 6).

For another article against Felix see R’ Yonah Merzbach,

Aleh LeYonah (2102), pp. 535-539. About Y. Felix see Zohar Amar article in

Jerusalem and Eretz Yisroel 4-5(2007), pp. 7-10. Available

here.

[1] In the next version of this article I will cite sources about this, IYH.

[2] חוט המשולש, כט ע”א.

[3] הגדול ממינסק, ירושלים תשנ”ד, עמ’ 51.

[4] שו”ת אהל יוסף, ניו יורק תרס”ג, בהקדמה.

[5] On this work there is extensive literature. See for example Bezalel Safran: Azariah de Rossi’s Meor Eynaim, PhD, Harvard 1979 (Thanks to Menachem Butler for this source); Robert Bonfil: Azariah De’ Rossi Selected chapters from Sefer Meor Einayim, Jerusalem 1991; Lester Segal: Historical Consciousness and Religious Tradition in Azariah de’ Rossi’s Meor Einayim, New York 1989.

[6] Toledot Rabi Azariah min ha-Adumim, Kerem Hemed 5 (1841) pp. 131-58; Tosefot le-Toledot R’ Azariah min ha-Adumim, Kerem Hemed 7 (1843) pp. 119-24.

[7] Gil Perl, The Pillar of Volozhin: Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin and the World of Nineteenth-Century Lithuanian Scholarship, Boston: Academic studies Press 2013, pp.105-126. This is the subject of a future article.

[8] On the Tzemach Dovid see Shimon Brisman, History and Guide to Judaic Dictionaries and Concordances, Ktav 2000, p. 61, 290.