The New Encyclopaedia Judaica: Some Preliminary Observations

by

Shnayer Leiman 1. In 1972, the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica appeared in print. With 25,000 entries, it moved well beyond its distinguished predecessors, such as the Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1906), the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1939-43), and the short-lived German language Encyclopaedia Judaica (Berlin, 1928-34). Its special focus on the Holocaust and its aftermath, on the State of Israel, and on the centrality of the Jewish community in the United States, rendered it the most current and useful of all the Jewish encyclopedias. But 35 years have passed since its publication, and there was a felt need for a new version that would update many of the entries in the light of scholarly advance. Also, new entries had to be provided for all that was new in Jewish life during the past 35 years. Early in 2007, the 22-volume second edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica appeared in print – in hard copy and electronic versions – and it was heralded as yet another milestone in the history of Jewish encyclopedias.

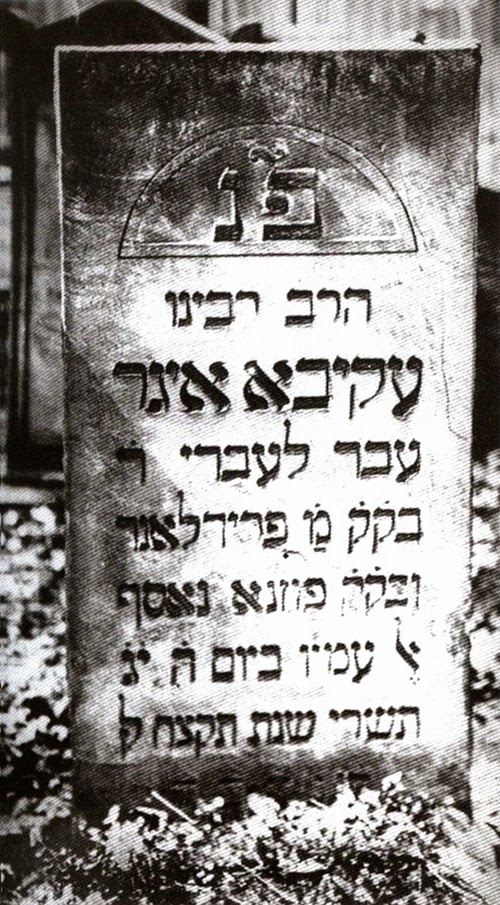

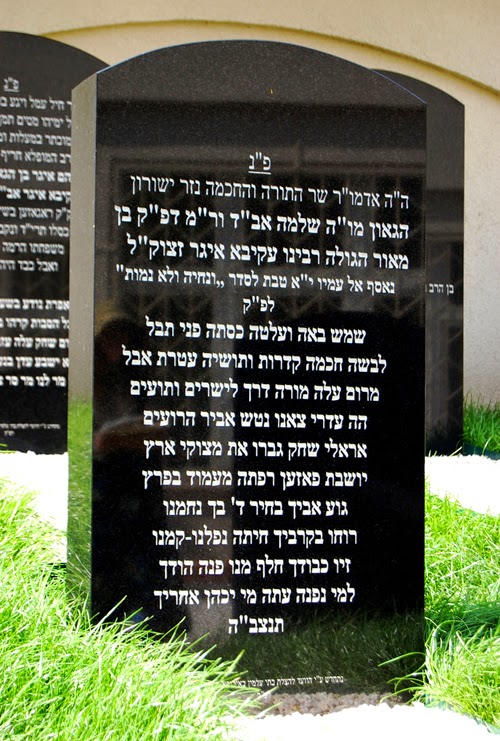

2. A striking difference between the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica (henceforth: EJ) and the second edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica (henceforth: NEJ [= new Encyclopaedia Judaica]) is the almost complete lack of visual images in NEJ. Whereas EJ contained some 8000 photographs and portraits (judiciously selected from a larger pool of 25,000), NEJ has only 8 pages of photographs in the center of each volume. Thus, for example, the entry on Solomon Dubno (d. 1813) in EJ is accompanied by a striking portrait of him [reproduced below]. The portrait is lacking in NEJ. Similarly, the entry on Vilna in EJ is accompanied by some 9 photographs that make the city come to life; none appear in the NEJ entry on Vilna. The almost complete lack of visual images in NEJ is a fatal flaw that renders it the least attractive (and arguably, the least informative, for often pictures inform even more than words) of all the Jewish encyclopedias listed above in paragraph 1.

3. One of the key selling points of NEJ is that it updates – and allegedly supersedes – the 1972 edition of EJ. In the general introduction to NEJ, we are informed that more than 2,650 new entries were incorporated into NEJ, and that over half of the original entries (in EJ) were revised and updated for NEJ. Indeed, it is a delight to see entries in NEJ for Dina Abramowicz, Zvi Ankori, Gerson Cohen, Lucy Dawidovich, Marvin Fox, Ismar Schorsch, Yosef Yerushalmi and the like – none of whom were accorded entries in EJ. But upon inspection, it turns out that many key entries that needed to be revised and updated were neither revised nor updated. And regarding the new entries, there are serious errors of commission and omission.

Samples of entries that should have been updated, but were not, include:

a) Abraham b. Elijah of Vilna (d. 1808). NEJ reprints EJ, apparently unaware that some 130 printed pages of Abraham b. Elijah of Vilna’s writings on Bible, Talmud, Midrash, and Jewish bibliography were published for the first time, from manuscripts, in 1998 (see Yeshurun 4[1998], pp. 123-254). EJ and NEJ list Abraham b. Elijah of Vilna’s date of birth as 1750. Recent historical studies indicate otherwise and suggest he was born in 1766 (see, e.g., Yeshurun 14 [2004], pp. 982-996). These and other post-1972 studies on Abraham b. Elijah of Vilna surely merited mention in a revised and updated entry. In this instance, NEJ does not reflect the present state of modern scholarship.

b) Adam Ba’al Shem. NEJ reprints the EJ entry by Gershom Scholem, who – in one of the most controversial passages he ever wrote – identified the writings of the Sabbatean prophet Heshel Zoref (d. 1700) with the writings ascribed by Hasidic lore to the legendary Adam Ba’al Shem. The latter’s writings, according to Hasidic legend, formed the basis for the uniquely Hasidic teachings of R. Israel Ba’al Shem Tov. Scholars were quick to challenge Scholem’s identification during his lifetime and after his death. None are cited in the NEJ entry. An entire literature has grown around this particular issue. Much (but not all) of the relevant bibliography appeared in Y. Liebes, ed., גרשם שלום: מחקרי שבתאות, Tel Aviv, 1991, pp. 597-599. None of this appears in the NEJ entry. Once again, NEJ does not reflect the present state of modern scholarship.

c) Chajes, Zevi Hirsch (d. 1855). NEJ reprints the EJ entry. In the intervening years, numerous studies and two major books were published on Chajes, none of which is mentioned in NEJ. Here it will suffice to mention the titles of the two books:

Bruria Hutner David, The Dual Role of Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Chajes: Traditionalist and Maskil, Columbia University Ph.D., University Microfilms, 1971.

Mayer Herskovicz, רבי צבי הירש חיות, Jerusalem, 1972 (reissued: Jerusalem, 2007).

Here too, NEJ does not reflect the present state of modern scholarship.

d) Kalmanovitch, Zelig (d. 1944). NEJ reprints the entry in EJ. The diary (mostly in Yiddish and partly in Hebrew) of this Yiddish scholar — and victim of the Holocaust – is one of the most poignant of the Holocaust diaries. In 1977, Kalmanovitch’s son, Shalom Luria, publish an annotated Hebrew translation of the diary, together with a 50 page introduction that reveals much about Kalmanovitch that was not previously known. See Z. Kalmanovitch, יומן בגיטו וילנה, Tel Aviv, 1977, pp. 9-59. A sizeable and significant fragment of the diary, entirely in Hebrew, was discovered in the Lithuanian Central Archive in Vilna, and published in 1997. See Yivo Bleter 3(1997), pp. 43-113. None of this information appears in the NEJ entry. Regarding the Kalmanovitch entry, then, NEJ does not reflect the present state of modern scholarship.

e) Luria, David b. Judah (d. 1855). NEJ reprints the entry in EJ. No mention is made in either EJ or NEJ that a portrait of Luria is extant (in Vilna) and has been frequently published. See, e.g., Yahadut Lita,Tel Aviv, 1967, vol. 3, p. 62. More importantly, some 230 printed pages of Luria’s hiddushim on Bible, Mishnah, the Jerusalem Talmud, and Midrash Mishle, as well as responsa, were published for the first time, from manuscripts, in 1998-9. See Yeshurun 4(1998), pp. 489-647 and 6(1999), pp. 285-359. NEJ does not reflect the present state of modern scholarship regarding this entry as well.

4. Sins of commission are inevitable in any encyclopedia. The name of the game is to keep them at a minimum, and it is largely the responsibility of the editors to check and recheck possible misspellings, mistaken dates and facts, discrepancies, imaginary references, exaggerated claims, and the like. NEJ is not lacking in sins of commission in all of the above categories. One amusing instance will have to suffice for our purposes.

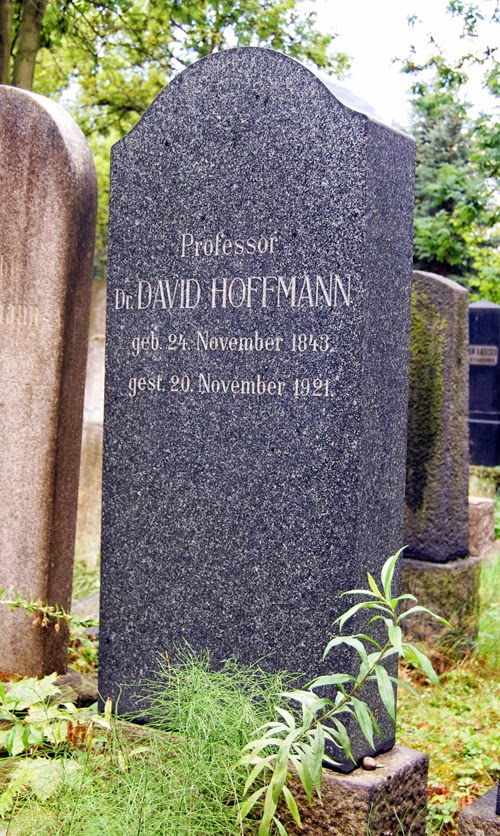

NEJ contains two entries of interest that appear several pages apart in volume 3. The first entry is entitled: Bloch, Chaim Isaac. The second entry is entitled: Bloch, Hayyim Isaac ben Hanokh Zundel Ha-Kohen. Innocent readers will assume, as they have every right to assume, that these represent two different persons. Alas, they are one and the same person. The first entry is a new one, designed especially for NEJ. The second entry is the old one, reprinted from EJ (minus the handsome photograph [reproduced below] that accompanied the original EJ entry). There are some interesting differences between the two entries. In the first entry, the reader is informed that Rabbi Bloch was born in 1867. Several pages later, however, Rabbi Bloch aged some 3 years, as we are informed that he was born in 1864. In the first entry, we are told mostly about essays he contributed to a variety of Torah journals – though mention is made of the fact that he published books as well. None of their titles are listed. In the second entry, not a word is said about his contribution to Torah journals. Instead, the titles of all his published works are listed. In the bibliographies appended to the two entries, each lists an item not in the other. The primary blame here hardly rests with the authors of the entries; presumably, they performed their assigned tasks as best they knew how. It is the sloppiness of the editors that allowed for the publication of two (sometimes contradictory) entries for one and the same person. Given the premium placed on space in any encyclopedia, this is a sin of no small import.

5. Sins of omission are inevitable in any encyclopedia. As the editors indicate in the general introduction to NEJ: “An obvious problem in the compilation of any encyclopedia is the decision as to which entries are to be included and which excluded …there is always a body of “borderline” entries which potentially could fall in either category. This problem becomes particularly sensitive when dealing with biographies of contemporaries. Which scholars receive entries and which do not? Where is the line to be drawn for rabbis or businessmen or lawyers or scientists? In some subjects, it was possible to fix objective criteria. For example when it came to U.S. Jewish communities, it was decided to include only those numbering more than 4,500.”

One can only sympathize with the impossible task before the editors. It was a no-win situation for them; whatever their decision, they would surely be open to criticism. If nonetheless I join the chorus of critics, it is not because of “borderline” entries. My own sense is that serious sins of omission occurred throughout NEJ, and in a broad range of categories. I shall attempt to illustrate this by selecting at random 5 categories of Jewish life that were of sufficient interest to me that I was even willing to leaf through the pages of NEJ in order to see how they were treated. I am well aware that others may consider unimportant what I consider important. What follows is no more than the personal opinion of one observer. The names listed below have no independent entry in NEJ and, at best, are mentioned in passing in other, often thematic entries.

a) Women. In the publicity relating to NEJ, it was stated openly that in earlier encyclopedias, including EJ, Jewish women were marginalized. They accounted for no more than 1.25% of the entries in EJ. This was a matter that would be rectified in NEJ. I do not know whether, in fact, this has been rectified in NEJ. But here are some omissions that seem striking to me.

1. Adele Berlin. A noted Bible scholar in the Department of Hebrew and East Asian Languages at the University of Maryland, her published books include:

Biblical Poetry Through Medieval Jewish Eyes; Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism; Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative; JPS Bible Commentary: Esther; Lamentations: A Commentary; Zephaniah: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary; and more.

2. Esther Rubinstein (1883-1924). An early advocate of religious Zionism, she was a leading Hebraist, Zionist, educator, and social activist in Vilna. Her learned essays on women’s suffrage paved the way for a change in rabbinic attitudes toward this issue. She founded the first religious day school for Jewish women in Lithuania. See the entry in אנציקלופדיה של הציונות הדתית, Jerusalem, 1983, vol. 5, columns 582-585.

3. Rivka Schatz-Uffenheimer (d. 1992) served as Edmonton Professor of Jewish Mysticism at the Hebrew University. Her many books on Kabbalah and Hasidut (e.g., Hasidism as Mysticism; The Thought of R. Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto [Hebrew]; The Messianic Idea from the Spanish Exile On [Hebrew]; R. Dov Baer of Mezhirech’s Maggid Devarav Le-Yaakov: An Annotated Edition [Hebrew] ) are landmarks in the history of Jewish mysticism.

4. Sara Schenierer (1883-1935), educator and author, founded the first Beth Jacob school in Cracow in 1917. In 1923, she founded the first Beth Jacob teacher’s seminary, also in Cracow. By 1927, there were 87 Beth Jacob schools, with over 10,900 students, in Poland alone. The movement spread throughout Europe, and ultimately to the United States and Israel, where it continues to thrive – with well over 50,000 students – to this very day. She also spearheaded a Jewish youth movement for young girls in Poland, wrote children’s literature and plays. Her collected writings were published in 4 volumes in Hebrew in Tel Aviv, 1955-60.

b) Rabbis.

1. R. Shneur Kotler (1918-1982) succeeded his father, R. Aharon Kotler, as Rosh Yeshiva of the Lakewood Yeshiva. He served in that capacity from 1962 until his death. Under his watch, the Lakewood Yeshiva grew from a student body of 200 students to a student body of over 1000 students. He established a system of Kollels throughout the larger Jewish communities in the United States. He was active in Agudat Israel, Chinuch Atzma’i, Torah U-Mesorah and other educational organizations. It was largely due to his leadership that the Lakewood yeshiva and its affiliate institutions number today well over 4000 students.

2. R. Eleazar Menachem Shach (1898-2001) was Rosh Yeshiva of the Ponevezh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak. From 1970 until his death, he was generally recognized by the Yeshiva world and by much of the Haredi world as the Gadol Ha-Dor. He was an occasional supporter of the Shas party, and was the founder of the Degel ha-Torah party. As such, he wielded enormous power in Israeli politics and the world over. He was the author of a monumental commentary on Maimonides’ Code, entitled Avi Ezri.

3. R. Yosef Shalom Elyashiv (b. 1910) succeeded Rabbi Shach as Gadol Ha-Dor. He is, arguably, the single, most powerful figure in the Yeshiva world and in much of the Haredi world. An expert in Jewish law, he has published some 26 volumes of hiddushim on the Talmud and Shulhan Arukh, as well as collections of responsa.

c) Academic Scholars. Two of the women listed above, Adele Berlin and Rivka Schatz-Uffenheimer, could just as easily have been listed under this rubric, with absolutely no bending of the rules. They were listed above only because of the claim that a special effort was made to include as many women as possible in the new entries for NEJ. Despite the claim, they were not accorded entries in NEJ.

1. Gerald Blidstein holds the Miriam Martha Hubert Chair in Jewish Law at Ben-Gurion University. His publications are simply too numerous to be listed here. Suffice to say that he was awarded the Israel Prize in Jewish Thought in 2006.

2. Menachem Cohen, Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University, is the head of the Mikra’ot Gedolot Ha-Keter Project – a project that is preparing for publication the Aleppo Codex and its Masorah, the Aramaic Targums, and critical editions of medieval Jewish commentaries on the Bible. Some 10 volumes have already appeared in print under his aegis. They represent the finest edition of Mikra’ot Gedolot ever produced.

3. Yehuda Liebes holds the Gershom Scholem Chair in Kabbalah at the Hebrew University. His many publications include: Studies in the Zohar; Studies in Jewish Myth and Jewish Messianism; and Elisha’s Sin (Hebrew). His annotated versions of Scholem’s studies are indispensable for scholarly research.

4. Haym Soloveitchik, University Professor at Yeshiva University, taught for many years at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Yeshiva University. His published books include: Halakhah, Economics, and Communal Self Image (Hebrew); Pawnbroking in the Middle Ages (Hebrew); Wine of Non-Jews (Hebrew); Responsa as Historical Sources (Hebrew). Some of his shorter essays (e.g.“Three Themes in Sefer Hasidim”; “Rupture and Reconstruction”) have stimulated more discussion than books by others on the same topics. He was a recipient of the prestigious National Foundation for Jewish Culture Jewish Cultural Achievement Award in Jewish scholarship.

5. Yaakov Sussman is a world class Talmudic scholar who was awarded the Israel Prize for Talmudic Research in 1997. His many publications on the manuscripts, editions, and the history of the publication of the Mishnah, the Jerusalem Talmud, and the Babylonian Talmud; his edition of the “Miqsat Ma’aseh Torah” fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls; and his edition of the Rechov inscription are the point of departure for all scholarly discussion of those topics.

d) Jewish Communities. As noted above, NEJ allows for an entry on any Jewish community in the United States with 4,500 Jewish residents or more. Thus, e.g., there is an entry on Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania which, perhaps, once had that many Jewish residents. According to the entry in NEJ, there were only 3000 Jewish residents in Wilkes-Barre in 2005. It is therefore somewhat surprising that there are no separate entries in NEJ on:

1. Monsey, N.Y.

2. Teaneck, N.J.

3. Far Rockaway, N.Y.

4. Lawrence, N.Y.

5. Cedarhurst, N.Y.

6. Woodmere, N.Y.

7. Kew Gardens Hills, N.Y.

I do not know the exact Jewish population of any of the towns listed above, but I suspect that each has at least 3000, and in all likelihood more than 4500, Jewish residents. In all fairness, NEJ presents a somewhat detailed discussion of Monsey and Teaneck under other rubrics (Rockland County and Bergen County). But I could not locate any discussion of Far Rockaway, the Five Towns, or Kew Gardens Hills. Each of these communities has a rich history, with many

synagogues, schools, and often institutions of national and international repute. They surely merit entries in NEJ.

6. The previous paragraph presents a rather long list of sins of omission relating to women, rabbis, academic scholars, and Jewish communities. One could easily add more names to each of the categories; and certainly so if yet other categories are examined. Doubtless, some will argue that there is simply no room in a 22-volume encyclopedia for so many “borderline” entries. In order to counter such an argument, I will list here four entries – exactly as they appear on the printed page – that found their way into NEJ.

1. Calwer, Richard (1868-1927). German socialist, economist, and politician. He belonged to the reformist wing inspired by Ferdinand Lasalle within the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). Calwer harbored a strong anti-Jewish bias. In a brochure published in 1894, he attacked the SPD’s radical wing as having been “incited by a few Jews who make slander their business,” and deplored that such “specific” Jewish characteristics as “zealousness, contentiousness, and commercial craftiness” had found their way into the party press and literature. He also criticized the SPD for combating anti-Semitism to the extent of creating the impression that Social Democracy had been “Judaized” (verjudet). Calwer left the SPD in 1909. He was a pioneer in Western socialist non-Marxian economics, which he taught until his suicide in Berlin.

2. Cohen, Philip Melvin (1808-1879), pharmacist and civic leader in Charleston, South Carolina. Cohen, born in Charleston, was the son of Philip Cohen, lieutenant in the War of 1812. During the Second Seminole War Cohen served as surgeon to a detachment of troops in Charleston Harbor (1836). In 1838 he became city apothecary. He was a member of the city board of health (1843-49). Cohen was a director of the Bank of the State of South Carolina (1849-55). He was one of the citizens who served as honorary guard at the funeral of John C. Calhoun in 1850.

3. Nagin, Harry S. (1890- ), U.S. civil engineer. Born in Romny, Russia, Nagin went to the U.S. in 1906. From 1924 he was executive vice president of a large steel products company in Pennsylvania. He took out over a hundred patents on steel structures, bridge floors, gratings, concrete, and plastics.

4. Abrams, “Cal” (Calvin Ross; 1924-1997), U.S. baseball player, lifetime .269 hitter over eight seasons, with 433 hits, 32 home runs, 257 runs, and 138 RBIS. Born in Philadelphia to Russian immigrant parents, he moved with his family to Brooklyn when he was a child. Having grown up in Brooklyn in the shadow of Ebbets field, Abrams fulfilled a life-long dream when he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers after graduating from James Madison High School. But after two weeks in the minor leagues he was drafted into the army., where he served four years. Abrams spent three years in the minor leagues, winning the Southern Association championship with Mobile in 1947 while hitting .336. Abrams, who batted and threw left-handed, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers (1949-52), Cincinnati Reds (1952), Pittsburgh Pirates (1953-4), Baltimore Orioles (1954-55), and Chicago White Sox (1956), and had a perfect fielding percentage in three different seasons, 1950, 1952, and 1956. Abrams is best remembered for one of the most famous plays in Dodger franchise history. In the final game of the 1950 season, with the Dodgers one game behind the Philadelphia Phillies in the pennant race, Abrams tried to score from second with two out in the bottom of the ninth of a 1-1 game on a hit by Duke Snider, but Abrams, who had been waved home by third base coach Milt Stock, was thrown out by the Phillies’ Richie Ashburn. Had Cal scored, the Dodgers would have won the game and forced a playoff with the Phillies for the pennant. Dick Sisler hit a three-run home run in the top of the tenth to win the game – and the pennant – for Philadelphia. It was the closest Abrams ever got to the post-season. Dodgers fans vilified Abrams for years but he was defended by both Ashburn and Phillies pitcher Robin Roberts for the play, who agreed with many others who said that Abrams should not have been sent home by Stock.

————————–

Far be it from me to deny Richard Calwer (a non-Jew), Philip Melvin Cohen, Harry S. Nagin , and Cal Abrams – not exactly household names – their rightful place in Jewish history. But at the expense of Professor Haym Soloveitchik? NEJ inherited the Calwer and Cohen entries from EJ. But the Nagin and Abrams entries are original with NEJ. In the case of Abrams, whose baseball career ended in 1956, this is somewhat surprising, for he obviously didn’t make the cut with EJ in 1972 (in contrast to Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax). Now I am well aware that Rav Shach could not hit major league pitching to save his life, and that his lifetime batting average would have paled in significance to Cal Abrams .269 lifetime batting average. But, really, does Cal Abrams take precedence over Rav Shach in a Jewish encyclopedia?

7. In sum, the returns are hardly in. Not for nothing did we label these comments “preliminary observations.” Much more needs to be investigated before one can judge how well NEJ has captured the totality of past Jewish life, and the pulse of present Jewish life, as reflected in the 2007 edition. But until all the returns are in, hold on to your 1972 edition of EJ for dear life! It is not at all clear that NEJ has superseded, or that it will ever supersede, EJ. All public libraries and private collectors will do well to retain their 1972 editions of EJ and keep them precisely on the same shelves they have now occupied for some 35 years.