A Picture and its One Thousand Words: The Old Jewish Cemetery of Vilna Revisited*

A. The Photograph.

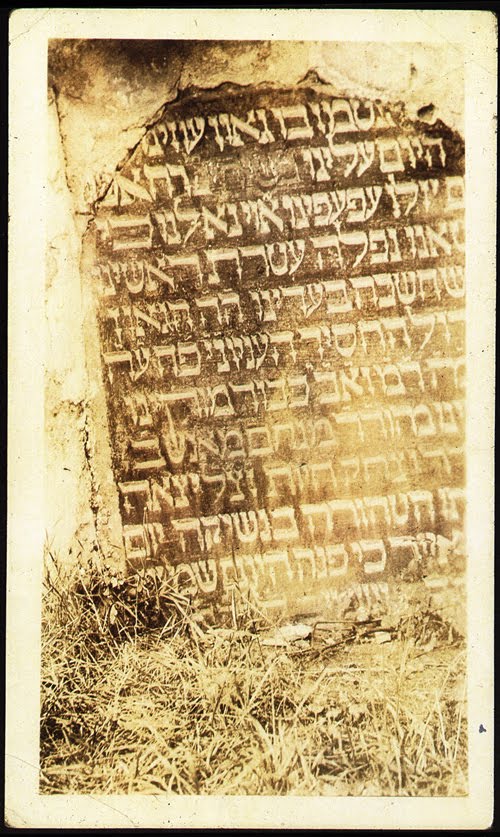

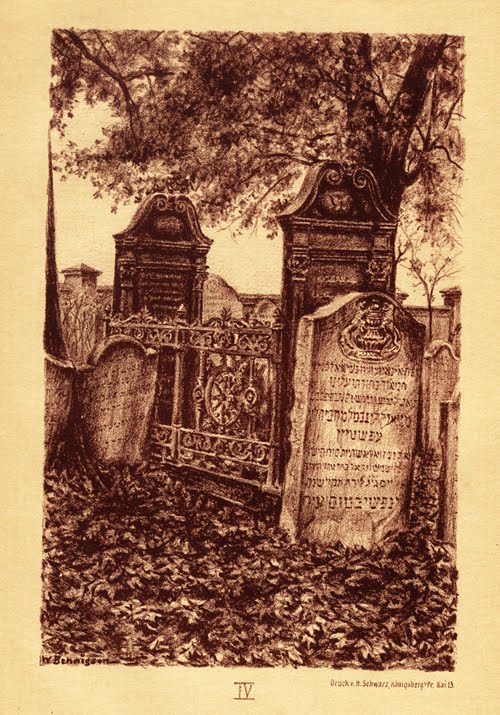

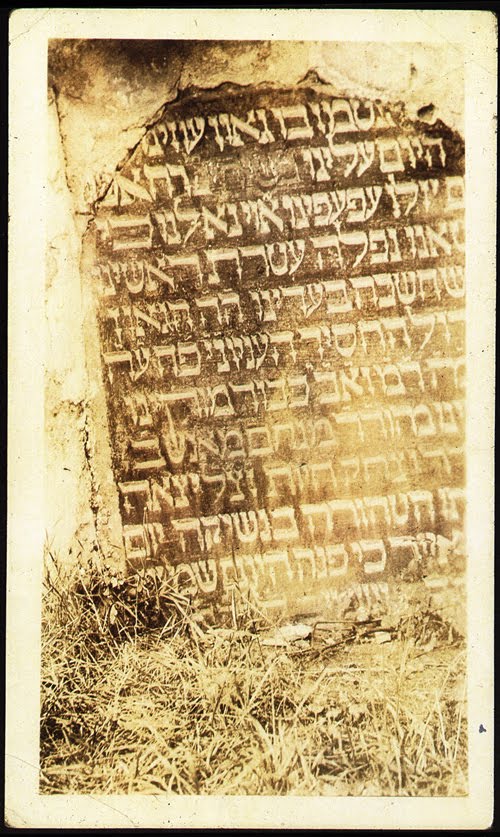

Recently, I had occasion to publish the above photograph – a treasure that offers a glimpse of what the old Jewish cemetery of Vilna looked like in the inter-war period.[1] Indeed, it captures the oldest portion of the rabbinic section of the old Jewish cemetery. The purpose of this essay is to identify the persons buried here and – where possible – to reconstruct and print the epitaphs on their tombstones. Seven partially legible inscriptions can be seen by the naked eye, as one moves from left to right across the photograph. An empty frame that once held a tombstone can be seen in the center of the photograph, as well. With the aid of a magnifying glass, as well as literary evidence, we shall attempt to identify all those buried here and to restore the full texts of their epitaphs. In effect, we shall engage in a virtual tour of a Jewish cemetery that – sadly — exists today almost entirely underground.

Briefly, the old Jewish cemetery was the first Jewish cemetery established in Vilna. According to Vilna Jewish tradition, it was founded in 1487. Modern scholars, based on extant documentary evidence, date the founding of the cemetery to 1593, but admit than an earlier date for its founding cannot be ruled out.[2] The cemetery, still standing today (but denuded of its tombstones), lies just north of the center of the city of Vilna, across the Neris (formerly: the Vilia) River, in the section of Vilna called Shnipishkes (Yiddish: Shnipishok). It is across the river from, and just opposite , one of Vilna’s most significant landmarks, Castle Hill with its Gediminas Tower. The cemetery was known as the Piramont[3] cemetery, also (in Yiddish) as der alter feld or der alter beys eylam [so in Lithuanian Yiddish; in Ashkenazic Yiddish: beys oylom]. It was in use from the year it was founded until 1831, when it was officially closed by the municipal authorities. Although burials no longer were possible in the old Jewish cemetery, it became a pilgrimage site, and thousands of Jews visited annually the graves of the many righteous heroes and rabbis buried there, especially the graves of the Ger Tzedek (Avraham b. Avraham, also known as Graf Potocki, d. 1749), the Gaon of Vilna (R. Eliyahu b. Shlomo, d. 1797), and the Hayye Adam (R. Avraham Danzig, d. 1820). Such visits still took place even after World War II.[4]

The cemetery, more or less rectangular in shape, was spread over a narrow portion of a sloped hill, the bottom of the hill almost bordering on the Neris River.[5] The photograph captures some of the oldest mausoleums and graves at exactly that spot, i.e. at the bottom of the hill almost bordering on the Neris River. The tombstone inscriptions face north, toward the top of the hill. As one moves from left to right across the photograph, one is in effect moving uphill toward the entrance of the cemetery, a gate built into the northern portion of the cemetery fence.[6] We shall move from left to right, and begin with the first tombstone inscription.

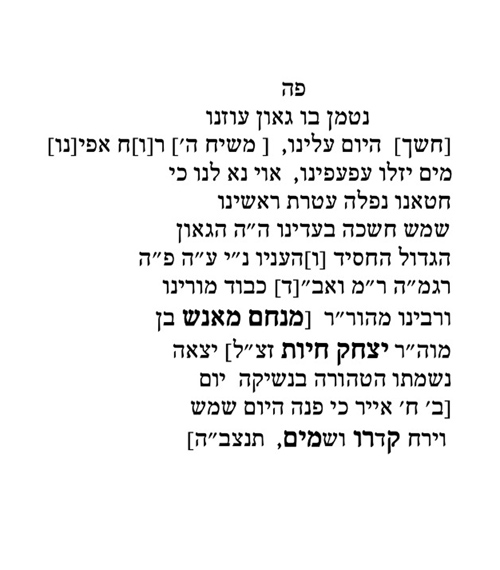

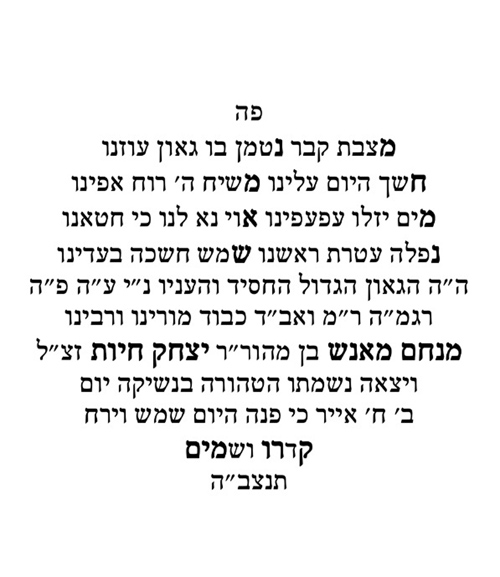

1. R. Menahem Manes Chajes (1560-1636).

R. Menahem Manes was among the earliest Chief Rabbis of Vilna. Indeed, his grave was the oldest extant grave in the Jewish cemetery, when Jewish historians first began to record its epitaphs in the nineteenth century.[7] R. Menahem Manes’ father, R. Yitzchok Chajes (d. 1615), was a prolific author who served as Chief Rabbi of Prague. Like his father, R. Menahem Manes published several works in his lifetime, including a dirge entitled סליחה על שני קדושים (Lublin, 1596)[8]; a treatise in rhyme encompassing all the laws of ערב שבת, entitled קבלת שבת (Lublin, 1621)[9]; and left still other works in manuscript form (e.g., a commentary on פרשת בלק, entitled דרך תמימים, now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University).[10] His epitaph reads:[11]

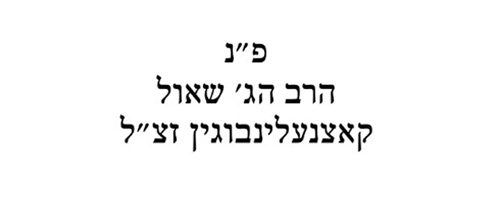

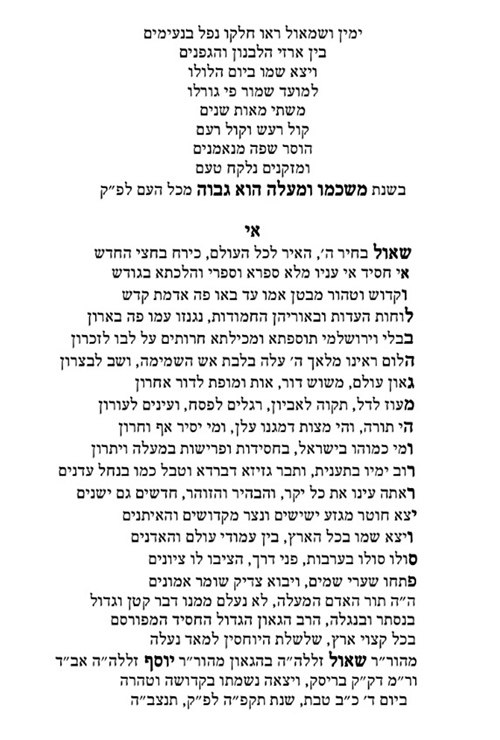

2. R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen (ca. 1770-1825).

Son of the Chief Rabbi of Brisk, R. Yosef Katzenellenbogen,[12] R. Shaul frequented Vilna as a youth in order to converse with the Gaon of Vilna. After meeting with the young Shaul, the Gaon purportedly said: “ראה זה רך בשנים וטעם זקנים מלא”.[13] Ultimately, R. Shaul settled in Vilna where he served with distinction as a מורה צדק. Influenced by the Gaon’s methodology and piety, it is no coincidence that he was asked to write letters of approbation for the first printed editions of works by the Gaon[14] and by (and about) his favorite disciples, R. Shlomo Zalman[15] (d. 1788) and his brother R. Hayyim of Volozhin[16] (d. 1821). R. Shaul’s glosses on the Talmud are included in the definitive edition of the BabylonianTalmud (ed. Romm Publishing Co.: Vilna, 1880-1886). He left an indelible impression on all who knew him; and especially on his students, among them R. David Luria[17] (d. 1855) and R. Samuel Strashun[18] (d. 1872) – two of the leading rabbinic scholars of 19th century Lithuania. He was honored at his death by being buried next to some of Vilna’s greatest rabbis, despite the fact that he was one of the last rabbis buried in the old Jewish cemetery. In 1826, a kloyz was established in Vilna in his memory. Called “Reb Shaulke’s [probably pronounced: Shoelke’s or Sheyelke’s] kloyz,” it remained in continuous use until, and even during, the Holocaust.[19]

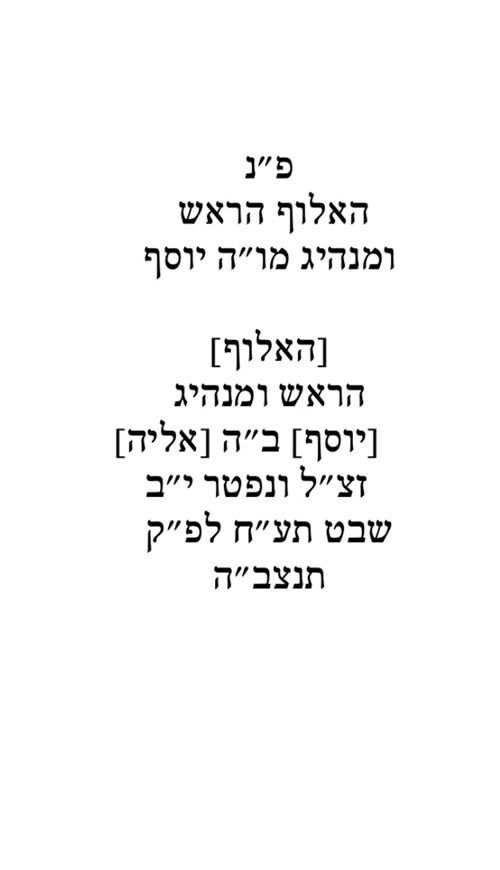

The inscription that can be seen on the photograph reads:

This is simply an informational sign (almost certainly of early 20th century origin) that indicates to the visitor that R. Shaul was buried in this mausoleum. In fact, he was buried between R. Menahem Manes Chajes (d. 1636) and R. Moshe Rivkes (d. 1672), author of באר הגולה, and ancestor of the Vilna Gaon. His tombstone inscription, not visible in the photograph, reads:[20]

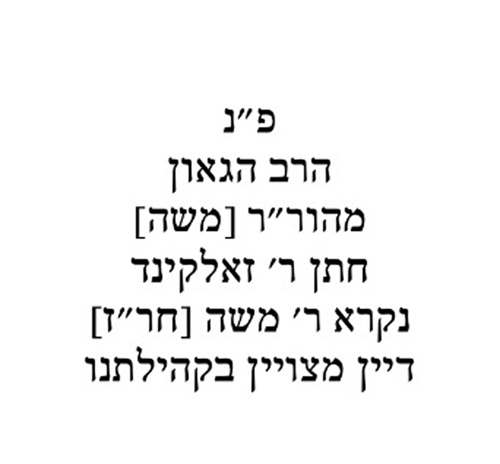

3. R. Moshe, Dayyan of Vilna (ca. 1670-1740).

Little is known about R. Moshe, other than – as indicated on his epitaph – he served with distinction as a dayyan in Vilna.[21] Some of his Torah teachings are preserved in his son R. David’s, מצודת דוד (Altona, 1736).[22] R. Moshe was popularly known as “R. Moshe Charaz,” חר”ז being an abbreviation for חתן ר’ זאלקינד “son-in-law of R. Zalkind.” R. Zalkind should probably be identified with R. Shlomo Zalkind b. Barukh, who lived in the second half of the 17th century, and was a respected lay leader of Vilna’s Jewish community.[23] R. Moshe’s epitaph stands outside a second mausoleum, with its own entrance, separate from the first mausoleum (where R. Menahem Manes Chajes, R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen, and R. Moshe Rivkes were buried). The epitaph reads:[24]

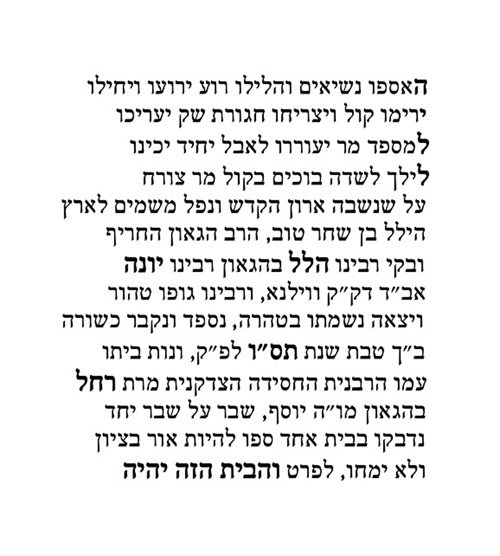

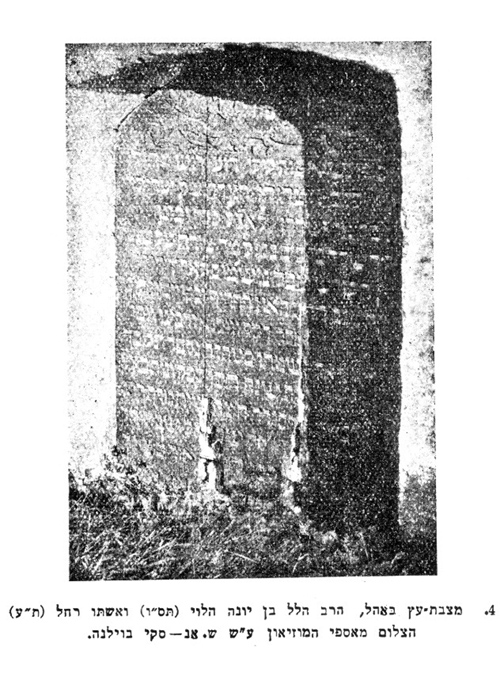

4. R. Hillel b. Yonah (d. 1706).

The empty frame in the third mausoleum from the left held a wooden tombstone that existed into the 20th century.[25] Before it was removed for repair, it was photographed in situ, and the photograph was preserved at the Ansky Museum in Vilna. The photograph was published just prior to the onset of World War II.[26] The epitaph on the tombstone commemorates the life and death of R. Hillel b. Yonah, Chief Rabbi of Vilna, and his wife Rachel (d. 1710). They were the only occupants of the third mausoleum. R. Hillel served as Chief Rabbi of Chelm prior to his appointment as Chief Rabbi of Vilna in 1688. Some of his Torah teachings are preserved in R. David b. R. Moshe’s מצודת דוד (Altona, 1736).[27] The joint epitaph reads:[28]

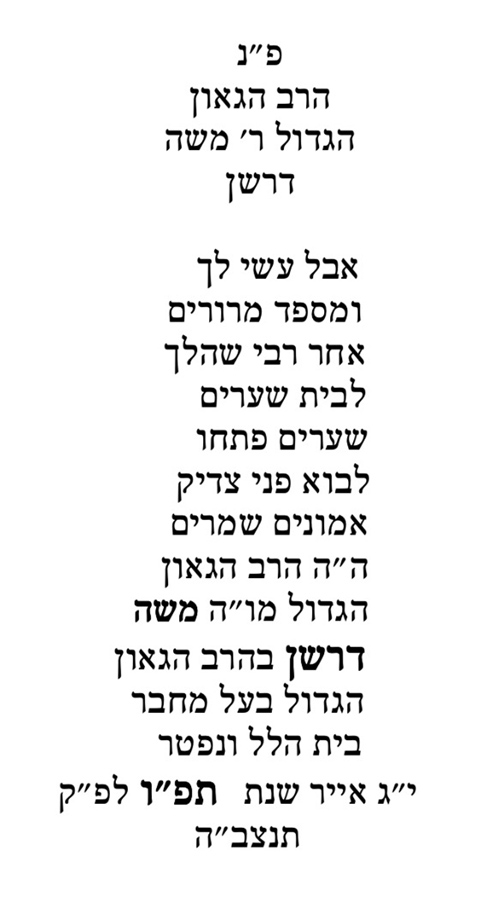

5. R. Moshe Darshan (d. 1726).

R. Moshe Darshan was born in Vilna in 1641. His father, R. Hillel b. Naftali Hertz, was the celebrated author of בית הלל (on Shulhan Arukh Yoeh De’ah and Even ha-Ezer), who served on the rabbinic court of R. Moshe b. Yitzchok Yehuda Lima of Vilna (author of חלקת מחוקק on Shulhan Arukh Even ha-Ezer) from 1651-1666, and later served as Chief Rabbi of Altona-Hamburg, and then Zolkiev.[29] R. Moshe was appointed ראש בית דין and דרשן of Vilna and served in that capacity until his death. His epitaph reads:[30]

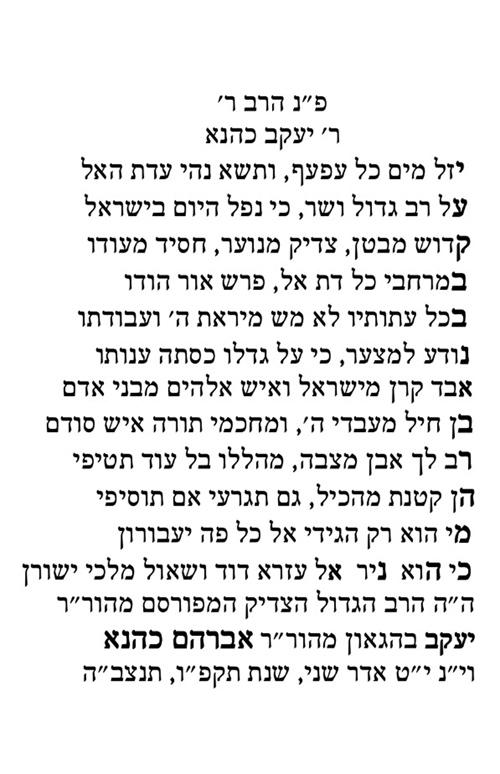

6. R. Yaakov Kahana (d. 1826).[31]

R. Yaakov b. R. Avraham Kahana, a disciple of the Vilna Gaon, was the son-in-law of R. Yissakhar Ber (d. 1807), a brother of the Vilna Gaon. Supported regally by his father-in-law, R. Yaakov suddenly found himself without support upon the death of his father-in-law. The Vilna kehilla immediately appointed him trustee of its various charities, in order to provide him with a dignified income, while enabling him to continue his pursuit of Torah study. R. Yaakov authored a classic commentary on B. Eruvin, גאון יעקב (Lemberg, 1863 and later editions).[32] His epitaph reads:[33]

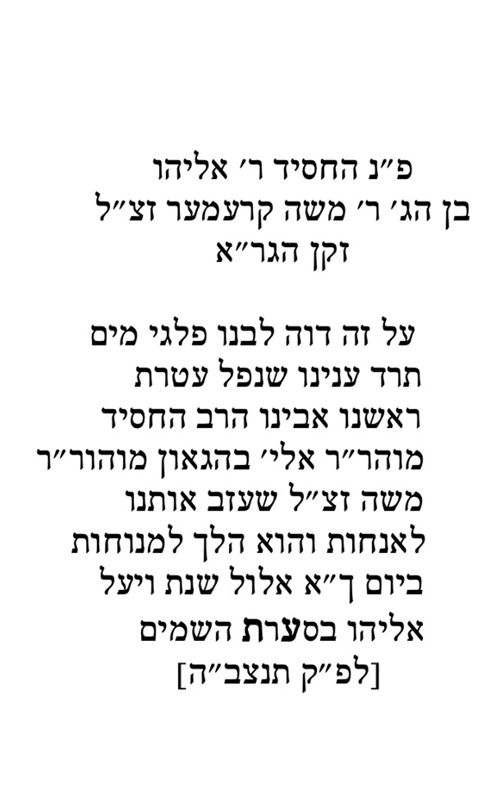

7. R. Eliyahu Hasid (d. 1710).

R. Eliyahu was the son of R. Moshe b. David Kramer, who served as Chief Rabbi of Vilna from 1673 to 1687.[34] R. Eliyahu served as an administrator of Vilna’s צדקה גדולה and also as a dayyan. He was a great-grandfather of the Vilna Gaon, and the Gaon was named after him.[35] The epitaph reads:[36]

8. R. Yosef b. Elyah (d. 1718).

A communal leader (ראש, אלוף, מנהיג) in Vilna about whom little else is known.[37] That he was buried in proximity to R. Eliyahu Hasid (d. 1710), and that at a later date R. Moshe Darshan (d. 1726) was buried in proximity to him, is sufficient proof of his prominence, perhaps in wisdom and certainly in wealth. His epitaph reads:[38]

————————-

B. A Visit to the Old Jewish Cemetery in 1940.

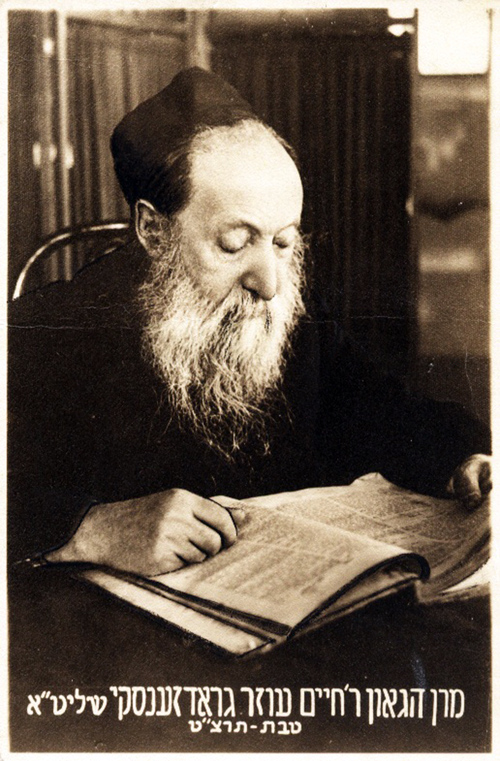

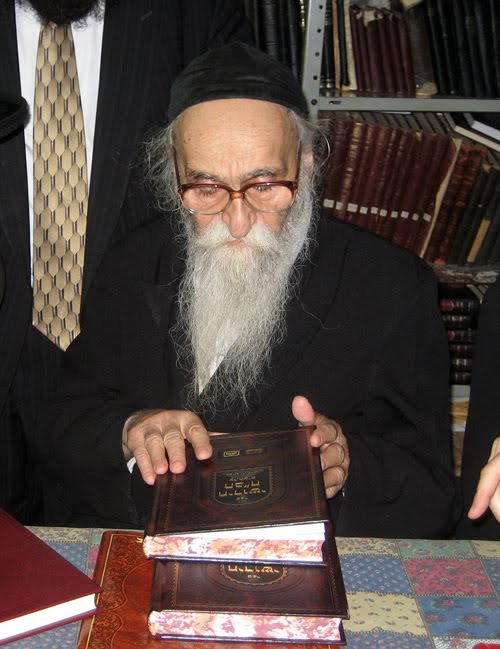

Known affectionately as “Reb Dovid,” Rabbi Meshulam Dovid Soloveitchik is currently Rosh Yeshiva of the Brisk Yeshiva in the Givat Moshe (also called: Gush Shemonim) section of Jerusalem. A descendant of R. Hayyim of Volozhin (d. 1821), and a scion of the Soloveitchik dynasty – his grandfather was R. Hayyim Soloveitchik (d. 1918), Rosh Yeshiva of Volozhin and Chief Rabbi of Brisk; and his father was R. Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik (d. 1959), last Chief Rabbi of Brisk, and founder of the Brisk dynasty in Jerusalem) – he is a leader of the Haredi community in Israel.

A still active nonagenarian, he was born circa 1923. Upon the outbreak of World War II, he fled from Brisk and made his way to Vilna, which – largely due to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 23, 1939, and Stalin’s subsequent decision to hand Vilna over to Lithuania – became the newly recognized capital of Independent Lithuania. Reb Dovid, a teenager at the time, resided in Vilna from October 22, 1939 through January 19, 1941, when together with his father (and other members of the family), he embarked on the arduous and dangerous journey that would bring him to the land of Israel, where the family ultimately settled.[39]

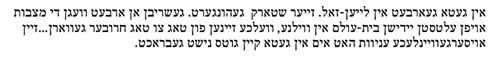

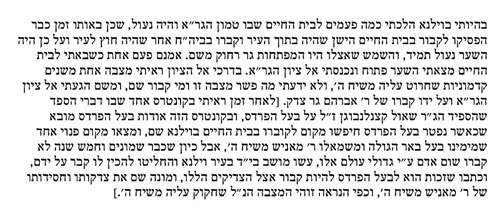

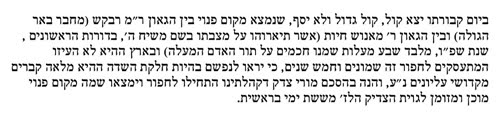

Some 15 volumes of Reb Dovid’s teachings have appeared in print, many under the title: שיעורי רבנו משולם דוד הלוי. These are transcriptions of his lectures as recorded by his students, with focus primarily on Torah and Talmud commentary. One of the volumes, however, includes a riveting account – in R. Dovid’s own words – of how he managed to survive the Holocaust. The memoir includes a brief description of a visit he made to the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna in 1940.[40] The passage reads:[41]

“When in Vilna, I went several times to visit the cemetery where the Vilna Gaon was buried, but it was closed. The gate was kept locked because burials no longer took place in the old Jewish cemetery, which was inside the city limits. Burials now took place in another cemetery [Zaretcha] which was outside the city limits.[42] Moreover, the caretaker who had the keys [to the old Jewish cemetery] lived far from the cemetery. Once, however, I came to the cemetery and found the gate open and went in to visit the Vilna Gaon’s grave. On my way to the grave, I passed an ancient tombstone with the words משיח ה’ inscribed on its epitaph.[43] I could not understand what this signified and who was buried there.[44] From there I reached the Vilna Gaon’s grave, and nearby, the grave of R. Avraham the Ger Tzedek. (At some later date, I chanced upon a pamphlet which contained a eulogy by R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen,[45] of blessed memory, over the author of Ha-Pardes.[46] In this pamphlet about the author of Ha- Pardes, it is stated that when he died a search was made in the old Jewish cemetery for a place where he could be buried. One empty plot was found, to the right of which was buried [R. Moshe Rivkes] the author of Be’er Ha-Golah, and to the left of which was buried R. Manes משיח ה’. Since no one had been buried in the empty plot next to these rabbis for some 85 years,[47] a rabbinic court was convened to decide whether the plot could be used now for the author of Ha-Pardes. The decision was that he should be buried between the two rabbis. They explained that it was a special privilege for the author of Ha-Pardes to be buried next to these righteous persons, and went on to describe the righteousness and piety of R. Manes משיח ה’. It seems likely that this was the tombstone I saw with the words משיח ה’ on its epitaph.”

This delightful account offers important testimony regarding what a living witness observed during a visit to the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna in 1940. On his way to the Vilna Gaon’s grave, R. Dovid saw a tombstone with the words משיח ה’ inscribed on its epitaph. The reference, of course, is to the grave of R. Menahem Manes Chajes (see above, epitaph 1). It is indeed nearby to the Gaon’s mausoleum, and one could easily stop to see it on the way to the Gaon’s grave. The alert reader will surely wonder why in the photograph taken in the inter-war period, which includes the epitaph of R. Menahem Manes Chajes, one cannot make out the words משיח ה’, whereas R. Dovid testifies that in 1940 it was precisely those words that caught his attention. The answer, I believe, is provided by another photograph of R. Menachem Manes Chajes’ epitaph taken in the summer of 1936.[48]

It too, at first glance, seems to have the words משיח ה’ erased. But if one examines the photograph closely, one can make out the words משיח ה’. The white paint that once covered these etched letters has been chipped off. The inter-war photograph, a “group” photograph taken from a distance, could not capture the etched letters that now appeared as black on black. The naked eye of a human being, however, could pick up the etched stone letters that read משיח ה’. So too, a close up photograph of the Chajes epitaph alone, taken in 1936.

R. Dovid adds that, subsequently, he chanced upon a pamphlet that helped him identify the epitaph he had seen. The pamphlet contained a eulogy by R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen over the author of Ha-Pardes, who apparently died in Vilna. Initially, an appropriate burial place could not be found for him in the old Jewish cemetery. But after much search, an empty plot was found between R. Manes משיח ה’ and [R. Moshe Rivkes,] the author of Be’er Ha-Golah. Since no one had been buried in proximity to these rabbis for some 85 years, a rabbinical court had to convene in order to decide the issue. The ruling was in favor of the burial, and special mention was made of the piety of R. Manes משיח ה’, which clearly identified the epitaph that R. Dovid had seen.

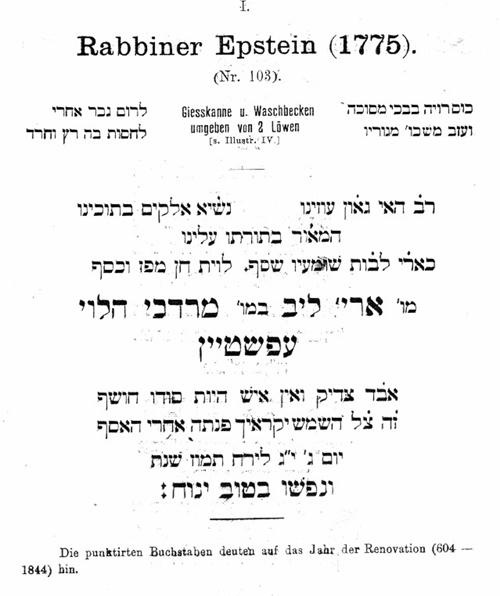

Sadly, I have not succeeded in locating such a pamphlet. If indeed R. Dovid saw such a pamphlet, he cannot be faulted for summarizing its content. It certainly enabled him to identify the epitaph as belonging to the tombstone of R. Menahem Manes Chajes. But problems abound. R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen (see above, epitaph 2) died in 1825. He wrote no pamphlets and published no eulogies. The author of Ha-Pardes was R. Aryeh Leib Epstein, chief Rabbi of Koenigsberg (today: Kaliningrad).[49] He died in 1775 and was buried in Koenigsberg.[50] Thus, R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen, five years old at the time, could not have published a eulogy over him. In fact, it was R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen (as described above in epitaph 2) – and not the author of Ha-Pardes – who was buried between R. Menahem Manes Chajes and R. Moshe Rivkes.

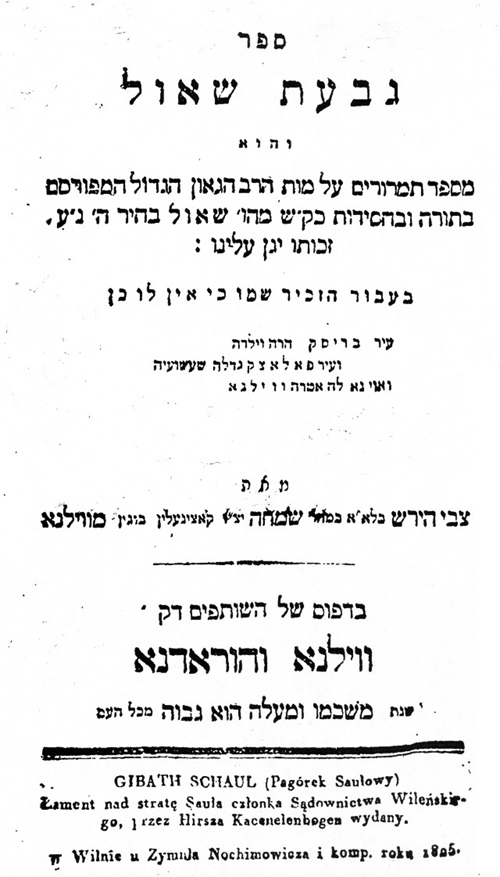

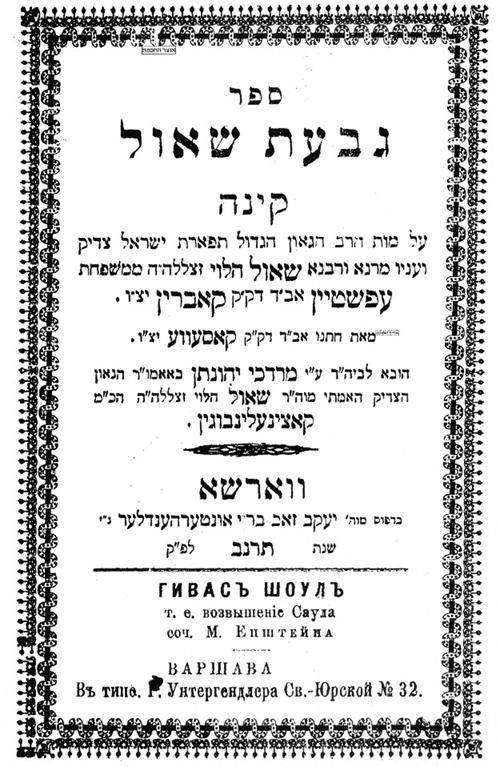

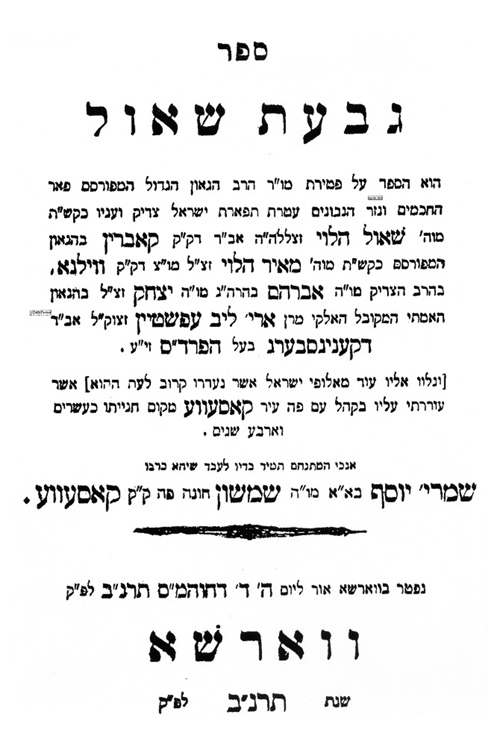

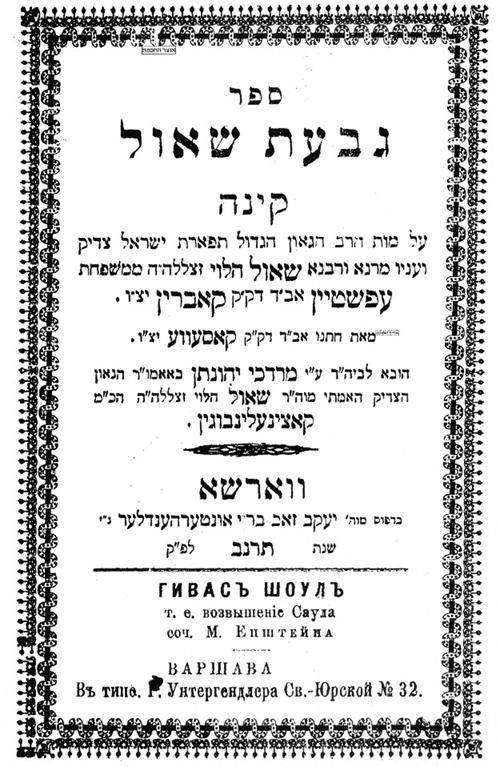

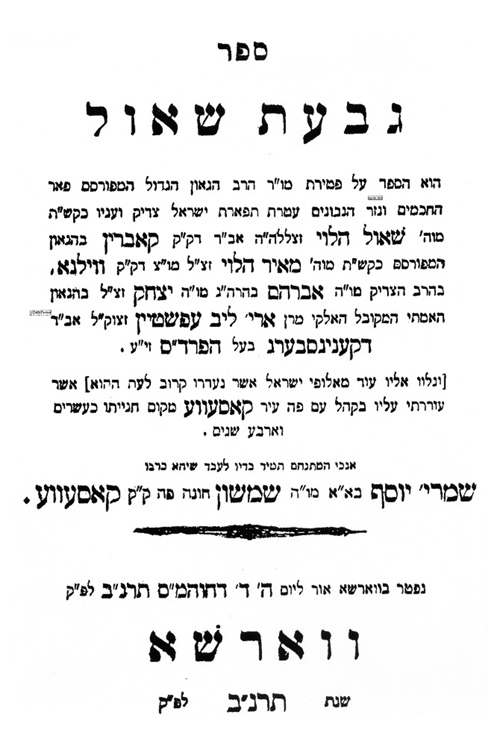

One suspects that the pamphlet R. Dovid chanced upon was R. Zvi Hirsch Katzenellenbogen’s גבעת שאול (Vilna and Grodno, 1825).

The author, a devoted disciple of R. Shaul,[51] published a eulogy upon the death of his teacher. He writes:[52]

“On the day of his [R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen’s] burial, an oracle was heard – a voice without pause[53] – that an empty plot had been found between R. Moshe Rivkes, author of Be’er Ha-Golah and the Gaon R. Manes Chajes (who was depicted on his tombstone as משיח ה’, already so in the early generations, in the year [5]386 [= 1626],[54] even aside from the seven virtues listed by the Sages that characterize all great individuals[55]). In that section of the cemetery, the gravediggers did not dare to dig a grave during the last 85 years, for they feared for their lives. For that section of the cemetery was filled with holy and pious Jews.[56] But due to an agreement of the Moreh Zedek’s of our community, they began digging and found an empty plot waiting for this righteous Rabbi’s remains since the week of Creation.

Here – and apparently in no other pamphlet – we have all the basic elements in R. Dovid’s account, with one glaring exception. Nothing is mentioned about the author of Ha-Pardes, R. Aryeh Leib Epstein. As indicated above, the author of Ha-Pardes in any event had nothing to do with a burial in Vilna. He lived at the wrong time (when empty plots were still available throughout the old Jewish cemetery) and died and was buried in the wrong place (in Koenigsberg). It is possible that we have in R. Dovid’s account a conflation of two unrelated pamphlets, each named גבעת שאול. Aside from R. Zvi Hirsch Katzenellenbogen’s גבעת שאול (cited above), a pamphlet with the exact same title, and also offering a eulogy, was authored by R. Shemariah Yosef Karelitz (d. 1917).[57]

The pamphlet, גבעת שאול (Warsaw, 1892), was a eulogy over Karelitz’ father-in-law, whose name also happened to be R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen (1828-1892), and who had served with distinction as rabbi of Kossovo and then Kobrin (both today in Belarus). This second R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen was a descendant of R. Aryeh Leib Epstein, author of Ha-Pardes. Indeed, on the first title page of Karelitz’ גבעת שאול, R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen is described in bold letters as a member of the Epstein family. On the second title page, he is described in bold letters as a descendant of “R. Aryeh Leib Epstein, author of Ha-Pardes.”

[

In sum, R. Dovid’s account provides impeccable testimony that the epitaph on the tombstone of R. Menahem Manes Chajes – the oldest tombstone preserved in the old Jewish cemetery – could still be visited and read in 1940.[58] What he claims to have read in a pamphlet at some later date remains problematic and requires further investigation or, as the later commentators would have put it, צריך עיון.

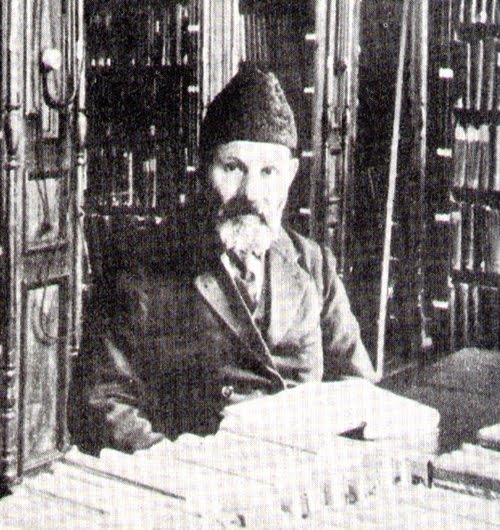

* In memory of Khaykl Lunski (ca. 1881-1943), fabled librarian of the Strashun Library, who was the embodiment of the very soul of Jewish Vilna. His last essay – a study of the faded tombstone inscriptions in Vilna’s old Jewish cemetery – was written in the Vilna Jewish ghetto created by the Nazis. It perished together with him during the Holocaust. See Shmerke Kaczerginski, חורבן ווילנע (New York, 1947), p. 198 (henceforth: Kaczerginski). Cf. Hirsz Abramowicz, Profiles of a Lost World (Detroit, 1999), p. 264. Kaczerginski’s description of Lunski’s last years in the Vilna ghetto are worth citing here:

Khaykl Lunski (ca. 1881-1943)

NOTES:

[1] Sid Z. Leiman, “Lithuanian Government Announces Construction of a $25,000,000 Convention Center in the Center of Vilna’s Oldest Jewish Cemetery,”

The Seforim Blog, September 13, 2015, available online

here, reprinted

here. A similar photograph (from a slightly different angle) appears in Leyzer Ran,

Jerusalem of Lithuania (New York, 1974), vol. 1, p. 100 (henceforth: Ran). Alas, its lack of clarity renders it mostly useless.

[2] See Israel Klausner, קורות בית-העלמין הישן בוילנה (Vilna, 1935; reissued: Jerusalem, 1972), pp. 3-5 (henceforth: Klausner). Cf. Elmantas Meilus, “The History of the Old Jewish Cemetery at Šnipiškes in the Period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania,” Lithuanian Historical Studies 12 (2007), pp. 64-67 (henceforth: Meilus).

[3] It was originally called “Pioromont,” because the old Jewish cemetery was adjacent to a street and neighborhood named after Stanislav Pior, an 18th century starosta who owned land in the area (Meilus, p. 88).

[4] See, e.g., the testimony of Chaim Basok, who together with Rabbi Kalman Farber visited the Vilna Gaon’s grave in the old Jewish cemetery at Piramont after Vilna was liberated by the Russian army in 1944. See Kalman Farber, אולקניקי ראדין וילנא (Jerusalem, 2007), p. 413. I have personally interviewed several former residents of Vilna who visited the Gaon’s grave in the old Jewish cemetery at Piramont between 1945 and 1948.

[5] A detailed map of the cemetery, as it appeared in 1935, is appended to Klausner.

[6] For an artist’s depiction of the gate at the northern entrance to the cemetery, see Sholom Zelmanovitch, דער גר-צדק ווילנער גראף פאטאצקי (Kovno, 1934), opposite p. 44. Notice Castle Hill at the upper right hand corner of the sketch; the inscription above the gate, והקיצו לקץ הימין; and the inscriptions on the sides of the gate, בית עולם ווילנא and zydu kapines. Here is the sketch:

[7] See, e.g., Shmuel Yosef Fuenn, קריה נאמנה (Vilna, 1860), p. 63 (henceforth: Fuenn 1860). Cf. the second and revised edition of קריה נאמנה (Vilna, 1915), p. 67 (henceforth: Fuenn 1915).

[8] Yeshayahu Vinograd, אוצר ספר העברי (Jerusalem, 1994), vol. 2, p. 359, entry 65.

[9] See Moshe Dovid Chechik, “ מהר”ר מנחם מאניש חיות וספר קבלת שבת,” ישורון 17(2006), pp. 668-691.

[10] Adolf Neubauer, Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library and in the College Libraries of Oxford (Oxford, 1886), column 59, entry 293.

[11] We have attempted to transcribe the Hebrew texts exactly as they appear in the photograph. We add in brackets the reconstruction of letters and words that in all likelihood once appeared in the original texts, but were no longer visible when the photograph was taken. For other photographs of the epitaph, see Klausner, p. 36; Zalman Szyk, יאר ווילנע 1000 (Vilna, 1939), pp. 408 and 416 (henceforth: Szyk); Ran, vol. 1, p. 101 ; and Reuben Selevan, A Trip to Remember: New York to Europe 1936 (New York, 2009), p. 113. The reconstructions are based mostly on the earlier transcriptions of the epitaphs in Fuenn and Klausner.

Over the years, some of the epitaphs were redone, and the reconstructed texts are often faulty. Enlarged and/or dotted letters (signaling acrostics, names, or dates) were sometimes made small and the dots were omitted. Small letters were sometimes enlarged. Letters and words were added or dropped when a partially erased word could no longer be read. Thus, for example, the first three words of R. Menahem Manes Chajes’ epitaph (in the photograph) read: פה נטמן בו, an impossible construction in Hebrew. It is obvious that one or more words are missing from the opening line of the epitaph. It is also evident the first lines form an acrostic spelling out his name: מנחם מאנש. When the epitaphs were redone, the original line divisions were not always retained. For the letters in bold relating to the year of his death (קדרו ושמים), see below, note 54. Based upon the earlier transcriptions in Fuenn (Fuenn 1860, p. 63; Fuenn 1915, p. 67) and Klausner (pp. 36-39), and a measure of common sense, the original epitaph probably read:

[12] R. Shaul was also the brother of his father’s successor in the rabbinate of Brisk, R. Aryeh Leib (d. 1837). See Aryeh Leib Feinstein,

עיר תהלה (Warsaw, 1886), p. 30.

[13] Abraham Dov Baer ha-Kohen Lebensohn, אבל כבד (Vilna, 1825), section “תולדות הנאון,” p. 2.

[14] See ספרא דצניעותא (Vilna and Grodno,1820), page following title page.

[15] See R. Yehezkel Feivel, תולדות אדם (Dyhernfurth, 1809), vol. 2, page following title page.

[16] See R. Hayyim of Volozhin, נפש החיים (Vilna and Grodno, 1824), page following title page.

[17] Samuel Luria, “תולדות הרד”ל,” in R. David Luria, קדמות ספר הזהר (New York, 1951), pp. 12-14.

[18] See Hillel Noah Maggid Steinschneider, עיר ווילנא (Vilna, 1900), vol. 1, p. 163.

[19] See Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin, Giedrė Mickūnaitė, and Jurgita Šiaučiūnaitė-Verbickienė, Synagogues in Lithuania (Vilnius, 2012), vol. 2, p. 316, item 55. Cf. Ran, vol. 1, p. 112. (The alleged photograph of R. Shaulke’s kloyz in Ran is misidentified; cf. Synagogues in Lithuania, vol. 2, p. 348, n. 248.) The address of the kloyz was Szawelska (later: Žmudskij) [Yiddish: Shavli] 5 (today: Šiauliu 2). The original building no longer stands. During the Holocaust, the kloyz continued to serve as a prayer house and it housed a Yeshiva named in memory of R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzenski (d. 1940). See Kaczerginski, p. 209; cf. Zelig Kalmanovitch, יומן בגיטו וילנה (Tel-Aviv, 1977), pp. 83 and 100 (English edition: Zelig Kalmanovitch “A Diary of the Nazi Ghetto in Vilna,” Yivo Annual of Jewish Social Science 8[1953], pp. 30 and 47).

[20] Fuenn 1860, pp. 236-238; Fuenn 1915, pp. 237-239; Klausner, p. 75.

[21] See Fuenn 1860, p. 100; Fuenn 1915, p. 107; and cf. Klausner, pp. 43-44.

[22] See, e.g. מצודת דוד, pp. 3a, 7a, and 31a.

[23] Fuenn 1860, p. 107, paragraph 50, number 11; Fuenn 1915, p. 113, paragraph 51, number 11.

[24] The text of the epitaph was not recorded either by Fuenn or Klausner. However, it is easily restored by combining the general information they provide with the legible portions of the text in the photograph.

[25] There is good reason to believe that wooden tombstones once proliferated in the old Jewish cemetery, but they did not survive the ravages of time and circumstance. See, e.g., Klausner, p. 38 (who indicates that as late as 1810 the fee exacted by the חברא קדישא for stone tombstones was twice the amount exacted for wooden tombstones) and Szyk, p. 406 (who states that the majority of tombstones in the old Jewish cemetery were made of wood but did not survive). Only two wooden tombstones (in the old Jewish cemetery) survived into the twentieth century; those of R. Hillel b. Yonah and R. Yehoshua Heschel b. Saul, who served as Chief Rabbi of Vilna from circa 1725 until his death in 1749. For photographs of R. Yehoshua Heschel’s wooden tombstone, see Klausner, p. 52; Szyk, p. 416; and Ran, vol. 1, p. 101.

[26] Klausner, p. 42. Cf. Szyk, p. 416 and Ran, vol. 1, p. 100 (mostly illegible).

[27] See, e.g., מצודת דוד, p. 27a.

[28] Fuenn 1860, pp. 97-98; Fuenn 1915, pp. 104-105.

[29] See Eduard Duckesz, אוה למושב (Krakau, 1903), pp. 4-7.

[30] Fuenn 1860, pp. 99-100; Fuenn 1915, pp. 106-107; Klausner, p. 43.

[31] Moving from left to right on the photograph, R. Yaakov Kahana’s tombstone (tombstone 6) appears to the right of R. Moshe Darshan’s tombstone (tombstone 5). But as one walks uphill from the bottom to the top of the cemetery, one passes the three mausoleums, then the twin gravestones of R. Yaakov Kahana and R. Eliyahu Hasid (tombstone 7), and only then the grave of R. Moshe Darshan.

[32] For biographical information about R. Yaakov Kahana, see Fuenn 1860, p. 239; Fuenn 1915, pp. 239-240; and the third edition of Kahana’s גאון יעקב, entitled גאון יעקב השלם (Jerusalem, 1997), introductory pages. See also Yaakov Polskin, “ספר צוף דבש,” ישורון 4(1998), p. 270, notes 7-9.

[33] Here too, the photograph presents an empty frame. Only the opening lines (i.e. the marker identifying the grave) can still be read. The original epitaph is recorded in Fuenn 1860, p 240; Fuenn 1915, pp. 240-241. Klausner (p. 53) mentions Kahana’s grave but does not record the epitaph.

[34] For biographical information about R. Moshe Kramer, see Fuenn 1860, pp. 95-96; Fuenn 1915, pp. 102-103, and the references cited in the next note.

[35] See R. Avraham b. R. Eliyahu (the Gaon’s son), סערת אליהו (Vilna, 1889), p. 18. Cf. R. Yehoshua Heschel Levin, עליות אליהו (Vilna, 1885), p. 39, note 5.

[36] The opening lines (i.e. the marker identifying the grave) are painted on the upper portion of the tombstone. The epitaph is encased below the tombstone’s upper portion. For the epitaph, see Fuenn 1860, p. 99; Fuenn 1915, pp. 105-106; and Szyk, p. 408.

[37] See Fuenn 1860, p. 107; Fuenn 1915, p. 113.

[38] Here too the opening lines represent the marker identifying the grave, almost certainly added at a later date. For the epitaph, see Klausner, p. 43.

[39] See שיעורי רבנו משולם דוד הלוי: דרוש ואגדה (Jerusalem, 2014), pp. 390-396. For the date when R. Dovid left Vilna (January 19, 1941), we have followed Shimon Yosef Meller, הרב מבריסק (Jerusalem, 2003), vol. 1, p. 513.

[40] No precise date is provided by R. Dovid for his visit to the old Jewish cemetery. But since he arrived in Vilna on October 22, 1939, and his first attempts to visit the cemetery were thwarted, we assume the visit took place in 1940, the only full year he spent in Vilna. It is possible, however, that the visit took place late in 1939 or early in 1941.

[41] שיעורי רבנו משולם דוד הלוי: דרוש ואגדה (Jerusalem, 2014), pp. 393-394. The translation provided here is paraphrastic. The original Hebrew text reads:

[42] In 1940, Jewish burials were still taking place in Zaretcha, the successor cemetery to the old Jewish cemetery, which was closed in 1831. Zaretcha (today: Užupis), just outside the Old Town, and across the Vilenka River, was part of the Vilna municipality in 1940.

[43] In the latter part of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the northern gate was no longer used. One entered the old Jewish cemetery from a side entrance on Derewnicka Street. The path from the entrance would lead one to the section where R. Menahem Manes Chajes was buried (on the right) and to the mausoleum where the Vilna Gaon was buried (on the left).

[44] The biblical title משיח ה’ (see, e.g., I Sam. 24:7 and Lam. 4:20), rendered “the Lord’s anointed one,” was usually reserved for kings and would-be messiahs (by their followers), not rabbis. R. Dovid could not identify the occupant of the grave, perhaps because the line with the name מהור”ר מנחם מאנש simply didn’t resonate to a 17 year old yeshiva student. One could claim that the line with R. Menahem Manes’ name was no longer legible in 1940 (as it was not legible in the inter-war photograph that forms the basis of this essay), but this seems highly unlikely in the light of the Selevan photograph taken in 1936. See below, note 48. The Selevan photograph is a close-up photo, and R. Dovid was standing directly in front of the same tombstone. He had no trouble reading poorly painted words.

[45] See discussion below.

[46] See discussion below.

[47] R. Menahem Manes Chajes died in 1636; R. Moshe Rivkes died in 1672. Eighty five years after these dates would be between 1721 and 1757. Since, as we shall see, the author of Ha-Pardes died in 1775, “85 years” cannot be referring to the time that elapsed between their deaths and his. “100 years” and more would have been a more accurate estimate. See below, note 56, for a likely explanation of the “85 years.”

[48] Reuben Selevan, A Trip to Remember: New York to Europe 1936 (New York, 2009), p. 113. I am deeply grateful to the author for granting me permission to scan and post the photograph (taken by his father in 1936) of R. Menahem Manes Chajes’ epitaph.

[49] For a biography of R. Aryeh Leib Epstein, see R. Ephraim Mordechai Epstein, גבורות ארי (Vilna, 1870). Ha-Pardes, only partially published, was an encyclopedic work encompassing many different genres of rabbinic literature. It includes talmudic commentary, listing and exposition of the 613 commandments, responsa literature, halakhic codes, kabbalistic teaching, sermons, eulogies, and more. The first fascicle with the title ספר הפרדס was published in Koenigsberg, 1759. It is a available today in several editions, including: ספרי בעל הפרדס (Bnei Brak, 1978), 2 vols.; and ספרי הפרדס (Jerusalem, 1983), 4 vols. See also מעשה רב חדש (Bnei Brak, 1980), pp. 29-80.

[50] His grave is no longer standing. A sketch of his grave, as it looked in 1904, appears in Festschrift zum 200jahrigen Bestehen des israelitischen Vereins für Krankenpflege und Beerdigung Chewra Kaddischa (Koenigsberg, 1904), sketch IV. The full Hebrew epitaph is printed opposite p. XX.

[51] See the entry on him in Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1973), vol. 10, column 830.

[52] גבעת שאול, p. 23a. The translation here is paraphrastic. The Hebrew text reads:

[53] See Deut. 5:19 and Rashi’s comment ad loc.

[54] The year of R. Menahem Manes Chajes’ death was recorded on his epitaph with the words: קדרו ושמים. Several of these letters had protruding dots above them; the numerical value of the dotted letters yields the year of his death. At a very early period, some of the dots could no longer be read. Fuenn (1860, p. 63; 1915, p. 67) writes that he was able to make out dots above the letters ר, ו , and מ. But those letters alone could not possibly refer to his date of death. This passage indicates that in 1825, at least, the dotted letters also includedק and final ם, totaling [5]386 = 1626. On other grounds, we know that Chajes died in [5]396 = 1636, so it appears likely that the dotted letters also once included the י of ושמים. If not for Fuenn’s testimony, we would claim that the second word by itself, ושמים ( = [5]396) yields the year of Chajes’s death. Cf. Moshe Dovid Chechik (above, note 9), p. 675.

[55] See M. Avot 5:7.

[56] Given that this passage was written in 1825, “85 years” here refers to the period between 1740 and 1825. As the passage itself makes clear, the reference is to the many rabbinic greats who were buried in this section of the cemetery by 1740 – and not later. See above, epitaphs 1,3,4,5,7, and 8, all of which are samples that support the claim that after 1740 no rabbinic greats were buried in this section of the cemetery. Epitaphs 2 and 6 are in harmony with this claim. Epitaph 2 is the epitaph of R. Shaul Katzenellenbogen, the case at hand. Epitaph 6 (R. Yaakov Kahana) is dated 1826, a year after the case at hand and the publication of the passage in R. Zvi Hirsch Katzenellenbogen’s גבעת שאול.

[57] The father of R. Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz (d. 1953), author of חזון איש.

[58] I am deeply grateful to Professor Dovid Katz of Vilnius, mentor and colleague, whose astute comments have enhanced the final version of this essay.