Rabbi Yitzhak Hutner’s View of Torah Im Derekh Eretz and a Hidden Haskamah Rediscovered

Rabbi Yitzhak Hutner’s View of Torah Im Derekh Eretz and a Hidden Haskamah Rediscovered

Shmuel Lesher

Shmuel Lesher is the assistant rabbi of the BAYT (Toronto). He can be reached at shmuel.lesh@gmail.com

*Thanks to my father-in-law, Rabbi Hanan Balk, for sharing many of the works used to research this topic with me from his vast and eclectic personal library. Thank you to Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter, Rabbi Moshe Lieber, Rabbi Daniel Korobkin, Ezer Dienna, and Rabbi Ken Stollon for greatly improving this article. Thank you to Simmy Zieleniec for connecting me with the Levi family.

Rabbi Yitzhak Hutner: A Brief Biographical Sketch

R. Yitzhak Hutner (1906-1980), the longtime dean of Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin of Brooklyn, New York had a unique and eclectic approach to Torah, spirituality, and Orthodox society life in the 20th century. A student of the famed Lithuanian Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Alter (Elder) of Slabodka, and influenced by Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, R. Hutner brought a blend of Hasidic and Lithuanian creative spirituality when he made his way to America. He shared his poetic and philosophical ideas with his students through his maamarim (discourses) which were later recorded, edited, and presented in his magnum opus Pahad Yitzhak (1964-1982).

Published biographical material about R. Hutner is sparse and scattered.[1] Even more difficult to come by are definitive statements of policies or positions made by R. Hutner. Therefore when determining his position on the question of the admissibility of a Torah Im Derekh Eretz curriculum, an educational program designed for the combined study of Torah and secular studies, one has to piece together bits and pieces of evidence in order to arrive at even an approximation of his view.

In one of the few biographical works on R. Hutner, R. Dr. Hillel Goldberg begins by citing an anonymous student’s recollection of R. Hutner saying, “Regardless of what you hear quoted in my name, do not believe it unless I have told it to you personally.”[2]

Ironic as this quotation may be, I understand why R. Goldberg chose it to begin his biographical sketch. The citation — however accurate or “believable” — captures the challenge the persona of R. Hutner poses to the genre of biography. It seems as though R. Hutner intentionally obscured his public position on a number of issues, preferring to share his outlook with his students and others personally.

The Yeshiva Community’s Approach to Secular Studies

To appreciate the nuances of R. Hutner’s position on Torah Im Derekh Eretz, it is important to understand the American Yeshiva community of which he was part. In his study of the early and mid-20th century American Yeshiva world, William Helmreich describes three basic approaches that American yeshivas took to secular studies.

On one hand, Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan (RIETS), from its inception took a more open approach to secular studies. On the other extreme, yeshivas like Beth Midrash Gavoha of Lakewood, New Jersey and Telshe of Cleveland, Ohio completely forbade college attendance, notwithstanding that it is likely that many of their alumni did attend some level of advanced educational institution. A third group of yeshivas, including Ner Israel of Baltimore and Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim of New York landed somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. Although they discouraged college attendance, these yeshivas recognized that a college degree can be a necessary step for a yeshiva student to make a living. Because of this reality, many yeshivas took a more moderate stance on college attendance.[3]

It appears that Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin would most likely fit into the third category of yeshivas which discouraged college attendance but did not forbid it. R. Hutner, who had a powerfully personable and dominating personality, encouraged his students to devote themselves completely to Torah study. As one student put it:

I went to college and, while permitted, college was looked down upon. With some exceptions, the top fellows didn’t go. The strength of Rav Hutner’s personality-my feet trembled whenever I spoke to him-drew us all in. It enabled you to resist your more modern parents who often wanted you to go to college. He built up your ego and made you feel you were great.[4]

R. Hutner had a broader vision for the American Jewish community than just his own yeshiva’s success “It is only a matter of time,” R. Hutner commented to Shmuel Avigdor when asked in an interview in the 1960’s what he thought about the future of the American Jewish community he inhabited and helped create and foster. R. Hutner told Avigdor:

It is obvious that it will not be exactly the same as the European Judaism that existed before the Shoah. It will have its own unique character. It will have its own ‘kineitch’ (personality or character). But it will be a Judaism that is complete and authentic — A Judaism not embarrassed of our former generations. Even today we already have American-born avreikhim (married kollel fellows) who are gedolei torah (great Torah scholars) in the original and authentic sense of the word. It is true that their greatness in the Torah is currently measured by the greatness in the style of Poland and Lithuania and there is no ‘greatness’ in the American style yet. But this will come with time, it’s all a matter of time.[5]

The American Yeshiva community, in R. Hutner’s eyes, although it would be “American” with its own flavor and identity, must be modeled after the same idealism and single-minded focus on gadlus (greatness) in Torah that characterized the European community of the previous generations. In fact, Helmreich reports that R. Hutner was critical of Yeshiva University’s synthesis of Torah and secular studies, stating that “When they put the word ‘University’ in, they spoiled everything.”[6]

Notwithstanding the above evidence which suggests a less sympathetic view towards the combination of Torah and secular studies, R. Goldberg, one of R. Hutner’s biographers posits:

Rabbi Hutner rejected synthesis but not secular study, at least for a select few. The unexceptional Talmud student would be unable to cope with intellectual challenges to tradition that Western philosophy, historiography, and other branches of learning pose. For Rabbi Hutner himself, secular study was less central than for Rabbi Soloveitchik…To Rabbi Hutner’s unitive mind, secular study identified a domain of the sacred within itself, a procedure that amounted to Torah’s reclaiming what rightfully belonged to it; for Torah, said Rabbi Hutner, was the sovereign source of all that is sacred. Hence he saw neither a moral nor a technical justification for the citation of secular sources in his writings.[7]

R. Goldberg’s depiction implies that R. Hutner did, in fact, have a good deal of sympathy for secular studies, albeit only for the select few. Clearly, the evidence for R. Hutner’s position is somewhat mixed. R. Hutner’s view on Torah Im Derekh Eretz and secular studies is characteristically nuanced and even appears at times to be contradictory.

The Primary Sources

Understanding this, in order to best determine R. Hutner’s true perspective, I thought it wise to focus not on secondary sources and analysis, but on R. Hutner himself, the choices he made for himself and for his community, and his own writings. In addition to many years of intensive and single-minded yeshiva study, R. Hutner chose to study at the University of Berlin. However, it is hard to evaluate this choice as indicative of a worldview as it was only a short 4-month stint.[8] Although it does indicate some level of interest in secular and/or academic knowledge and the granting of some legitimacy to its study, albeit not necessarily for the masses.

When it comes to communal policy it appears that R. Hutner did, at least initially, support the study of secular subjects at the high school level. In the biography of Rav Dr. Joseph Breuer, the authors write:

Both R. Moshe Feinstein- rosh yeshiva of Mesifta Tiferes Yerushalayim on the East Side – and R. Yitzchok Hutner – rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Chaim Berlin in Brooklyn – had been a part of the planning process [in assisting Rav Breuer to open some form of a Torah Im Derekh Eretz Yeshiva High School for the Jewish community of New York].[9]

Because of opposition from other gedolim to the prospect of such a yeshiva high school, the school never actually got off the ground.[10] However, R. Hutner’s early support of a yeshiva high school that would have included a dual curriculum modeled after the Hirschian approach suggests a more sympathetic view of Torah Im Derekh Eretz.

R. Hutner not only supported the founding of a yeshiva high school with a dual curriculum, there is evidence that he even supported the founding of a form of yeshiva college. William Helmreich documents a fascinating development almost totally unknown today:

In 1946 a petition was submitted to the Regents of the University of the State of New York requesting a charter for a new institution to be known as the American Hebrew Theological University. The proposed college was to be formed by the merger of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath and Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin.[11]

The Board of Trustees of this institution included Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz (1886-1948), the menahel (principal) of Yeshivas Torah Vodaath, and, none other than, Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner. As with the yeshiva high school, although Yeshiva Torah Vodaath and Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin were granted a provisional charter on July 18, 1946, about a year later the application was withdrawn and the college was never formed.

It appears that the person responsible for this major reversal was Rabbi Aharon Kotler. According to Helmreich’s interview with Rabbi Harold Leiman,[12] then the principal of Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin high school and the person chosen as dean of this new college, after a long conversation between R. Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz and R. Aharon Kotler in which the latter expressed his strong opposition to the idea, the decision was made to abandon the project.[13]

Even though these schools never came to be, it appears from these accounts that R. Hutner did support the idea of founding a high school as well as a college founded upon the values of Torah Im Derekh Eretz. It is even clearer in the case of the proposed American Hebrew Theological University that R. Hutner was serious about the implementation of a dual-curriculum. The fact that a dean was selected and a formal request for a charter was submitted and granted indicates how far along in the process they were in bringing the school into existence even if they ultimately withdrew the application.

Evidence From R. Hutner’s Writings

The other area to look for evidence regarding our question is R. Hutner’s writings, primarily his letters. In a well-known letter (no. 94) to a student struggling with his transition from yeshiva into the workforce, R. Hutner emphasizes the ideal of bringing Torah values into the outside world. In his words:

Someone who rents a room in one house to live a residential life and another room in a hotel to live a transient life is certainly someone who lives a double life. But someone who has a home with more than one room has a broad life, not a double life.[14]

Although this letter does not directly support the study of secular subjects, it is clear from the content of his message that R. Hutner sees his student’s involvement in the world outside of the yeshiva as a broadening of horizons and not merely a necessary evil.

In another letter (no. 102) included in Igros Ukesavim, R. Hutner writes negatively about a certain kind of approach to a dual yeshiva curriculum (see below). First, R. Hutner praises a work he received, presumably written by his interlocutor. Afterwards, he refers to a particular passage in this work in which the author describes an ideal in which yeshiva students, in addition to many years of Torah study, engage in “yishuv” — agricultural work or the development of land. R. Hutner notes that this outlook of “Torah Umelakhah” — Torah study and work — appears to the [American] public as a “fifty-fifty” form of a dual curriculum and is completely the opposite of the vision of the author.[15] The thrust of the letter is that, in R. Hutner’s view, despite its popularity in the American Jewish Community, a dual curriculum is not an ideal for which to strive.[16]

Notwithstanding the skepticism found in the above letter, there is another significant piece of evidence that R. Hutner did in fact approve of the Torah Im Derekh Eretz approach. R. Hutner gave his own written endorsement of the ideal of Torah Im Derekh Eretz in the form of a haskamah — a formal rabbinic letter of approbation.

Yehuda (Leo) Levi’s Work and the Case of a Missing Haskamah

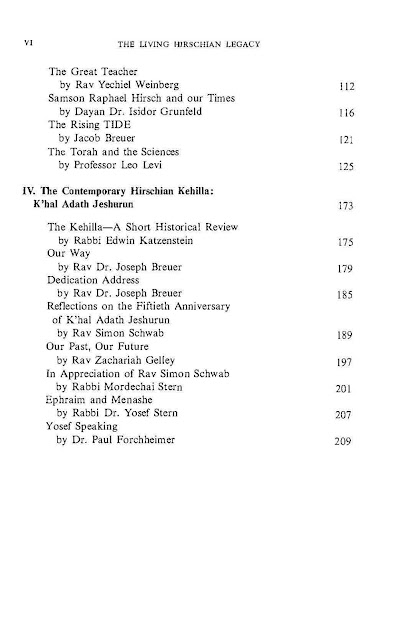

In the very first footnote of the very first article of The Torah Umadda Journal, effectively launching the entire publication, the editor, Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter, cites a letter written by R. Avraham Bloch. This letter, along with three other letters of European Gedolim regarding Torah Im Derekh Eretz was first published by Rabbi Prof. Yehuda (Leo) Levi. These letters were written in response to R. Shimon Schwab’s queries regarding the admissibility of a curriculum that included secular subjects in a yeshiva outside of Germany. R. Schacter writes that R. Bloch’s response was first published by R. Levi in 1966.[17][18]

In 1959, R. Levi wrote an earlier work, Vistas From Mount Moria, published by the Gur Ayeh Institute, the same institution that published Rav Hutner’s Pahad Yitzhak. It was his first published work on the topic of Torah and General Culture.[19] In the introduction to this book, the author makes reference to two endorsements, one of which, to my knowledge, has not yet been published.

In the introduction, R. Levi thanks “Rabbi Dr. Joseph Breuer” and “Rabbi Isaak Hutner” for their endorsements and constructive criticism. However, neither of these endorsements are printed in the volume but are said to be “available upon request.”

Almost 20 years later, R. Levi did include rabbinic endorsements for his work Shaarei Talmud Torah (1981). Endorsements are given by R. Yaakov Kaminetsky (Nissan 5740), R. Pinchas Menachem Alter of Gur (5740), R. Avraham Farbstein (5741), R. Aaron Soloveitchik (not dated), and R. Ovadiah Yosef (5747).[20]

Although both R. Breuer’s and R. Hutner’s endorsements of his other work are not included, R. Levi does write in his foreword to his 1990 work Torah Study (a translation of Shaarei Talmud Torah) that the Hebrew edition was published in 1981, when his “unforgettable mentor, HaRav Joseph Breuer, had explicitly expressed the wish that the author’s notes and essays be presented in a comprehensive and coordinated Sefer.” No mention of R. Hutner is made.[21][22]

I thought the story ended there. But to my great surprise and joy, in the course of researching this topic, I was connected to Yosef Levi, a son of Yehuda Levi who graciously shared the missing haskamah with me which I include along with a translation below.

The following pages, 155-157 (below), include the haskamah given by R. Dr. Breuer and R. Hutner:

Translation of Rav Hutner’s Endorsement

LETTER OF ENDORSEMENT

From the rabbi who is great in wisdom and fear [of heaven], the man to whom hidden things are revealed, my rabbi and teacher, Moreinu Harav Yitzhak Hutner, may his light shine, Rosh Mesivta Yeshivas Rabbi Chaim Berlin and Kollel Gur Aryeh

20 Elul 5719

My dear, honorable, and beloved Mr. Yehuda the son of R. Yosef Aharon Halevi, may his light shine,

Peace and blessings,

I remember when I was younger, I once had the opportunity to be within the orbit of one of the elder gedolim of the previous generation. Our conversation led to a discussion about Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch zt”l. This gadol then told [me] what he had heard in the year 5630 (1869-1870) from one of the unique [people] of the generation before him. In that year of 5630, news of R. Hirsch and his activities had reached Russia. There were those who had concerns about his approach, because it appeared that the study of Torah had not gained a proper footing within his activities and his educational approach. However, these concerns were not accepted by the gedolei hador of those days. And despite these doubters (naysayers), an attitude of loyalty towards R. Hirsch was established and his approach was deemed akin to [spiritual] rescue from the fire. In relation to this, this gadol then expressed the following: “The clearest proof that the intentions of Rav Hirsch were for the sake of Heaven will be found in the near future, that the desire for Torah study in the soul of the next generation of Rav Hirsch’s community will increase, and many of them will attempt to acquire additional Torah beyond what was taught by of the community’s educational system.” So were the words of that gadol.

This gadol’s words were right on the mark because we can see with our [own] eyes that during the period between the two World Wars, many benches in the yeshivas in Eretz Yisrael, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Galicia were filled with the descendants of R. Hirsch’s followers.

These recollections come up out of my memory when I encounter you, my dear. In terms of ancestry, you descend from a well-pedigreed family of German Jewry (from the descendants of the Maharal).[23] Accordingly you received your education in the ways of the great teacher of this [form of] Judaism. Your gifts have made you famous in the field of physics to the point that you have caught the eye of the government, which, because of the times, is now in need of first-rate scientific resources. At the same time, the hopes of that righteous man (referred to above) have been fulfilled in you; your heart is deeply inspired to commit yourself to Torah study in order to quench the great fire that burns within your soul. To this end, you have limited “derekh eretz” pursuits to only that which is absolutely necessary, and have established a place for yourself in our Beis Medrash Gur Aryeh. Because you have accomplished the dictum, “Make your occupation incidental and your Torah study primary” (Avos 1:15) we have witnessed your ascent in Torah study with great success.

However, even as you were planted in the Bais Medrash, you did not forget about those whose portions [in Torah] did not fall to them pleasantly, and who did not merit to be enhanced through entering into the tent of Torah. Because of your upbringing and background, you can sense the difference between the one whose perspective is from within the Temple courtyard and the one who is from a distance. When one drinks from the nearby springs and is able to place his lips to the flowing waters, the life essence of the water enters his very being and irrigates the “marrows of his bones.” His soul is renewed and his breath invigorated.

Not so for the person who is sustained by the water of the spring from a distance. He has to use pipes and various vessels that draw from different kinds of vessels (Esther 1:7) in order to access the water. The nature of running water is that it loses its freshness when it passes through the pipes. What’s more, by passing through pipes, the water picks up sediment and dirt on the way.

We know well that large group of people who, despite being prepared to accept the yoke of Torah and mitzvos, nevertheless, fail to have the water penetrate them with their normal purity and freshness, due to the fact that their lives have positioned them at a distance from the wellspring. They can only draw water that is blocked, occluded, and which has other ingredients mixed in.

Therefore, when you felt the spiritual distress of this group, your spirit pushed you into being their helper and assistant. It is for this purpose that you wrote a survey of topics in the realm of hashkafos and deos (Torah outlooks and doctrines), in order to preserve, in some way, the purity of the water for those who find themselves far away from the springs.

When you gathered together these different essays into one pamphlet with the title, Vistas from Mount Moria, you gave it to me with the request for an endorsement — I deem it correct to grant your request because I think it serves a great purpose for people of the group mentioned above as well as many who occupy the Beis Hamedrash.Just as you have been successful in the study of Torah, so shall you be successful in the pillar of kindness to bring close those who are far and to reveal the beauty of the Torah which you have found in the Beis Hamedrash to those who are found to be still outside of it.

With the hopes of raising the esteem of those who toil in Torah,

Yitzhak Hutner[24]

See Appendix for a different version of Vistas From Mount Moria. Both were published in 1959 (see facsimiles of both editions below) Although, if you compare the same pages (154-157) beginning from the back of this book, you will find that there are exactly the same amount of pages between page 154 and the Hebrew title page, however, they are all blank. Note the publication and year appear to be the same as the original version but the endorsements of both Rabbi Dr. Joseph Breuer and Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner are removed. This supports Yosef Levi’s explanation as to why the haskamah was hidden as I will address below.

Analysis of the Endorsement

R. Hutner’s letter of endorsement can be divided into two sections. In the first part of the letter, R. Hutner grants legitimacy to R. Samson Raphael Hirsch’s educational approach. In the second part of the letter he focuses on his student R. Levi and the importance of his work.

In the first part of the letter, in typically cryptic form, R. Hutner does not quote the gedolim who he is citing as approving of the Hirschian method. However, he clearly sees this positive view of R. Hirsch and his Frankfurt Kehillah as the definitive view. In his opinion, the descendants of the Frankfurt community joining the yeshivas outside of Germany in between the two world wars as a sign of the authenticity of R. Hirsch’s approach of combining Torah and worldly knowledge. One might argue though, that this reveals R. Hutner not to be a staunch proponent of the Hirschian philosophy as he only sees its legitimacy based on the Yeshiva Community’s criterion or a “Torah Only” standpoint and not a viable independent approach. R. Hutner praises the Frankfurt educational model not on its own merits but because it produced yeshiva students who eventually made their way to “Torah Only” institutions outside of Frankfurt.

Moreover, although R. Hutner grants legitimacy to R. Hirsch’s program and although he himself endeavored to create dual-curriculum institutions, it would be difficult to argue that he viewed Torah Im Derekh Eretz the same as did R. Hirsch.

Dr. Shnayer Z. Leiman, in his “Rabbinic Openness to General Culture,” cites a number of passages from R. Hirsch’s writings proving that R. Hirsch believed in the intrinsic value of Torah Im Derekh Eretz as an ideal for which to strive.[25] One citation from R. Hirsch’s work will suffice:

Culture starts the work of educating the generations of mankind and the Torah completes it; for the Torah is the most finished education of Man…culture in the service of morality is the first stage of Man’s return to God. For us Jews, Derekh Eretz and Torah are one. The most perfect gentleman and the most perfect Jew, to the Jewish teaching, are identical. But in the general development of mankind culture comes earlier.[26]

R. Hutner, who rejected the synthesis of Yeshiva University, presumably would not subscribe to R. Hirsch’s formulation of “Derekh Eretz and Torah being one.” That being said, and notwithstanding R. Hutner’s use of an external assessment of the Hirschian approach, I still believe R. Hutner personal admiration for R. Hirsch as well as for R. Levi does come through in this letter. The nameless gadol from the previous generation he cites approvingly, clearly saw R. Hirsch’s opponents as incorrect and not how the “leaders” of the previous generations viewed the issue.

The second part of the letter expresses clearly his deep appreciation, pride, and personal interest in R. Levi whom he saw as a future “thought leader” on how to approach the issues of Torah engaging with science and general culture. R. Hutner shares his concern about a particular subset within the Jewish community who have erred in their understanding of Torah. R. Hutner believed that R. Levi, a true Torah scholar of the first degree, someone who had an intimate knowledge of Torah as well as a deep understanding of culture, was uniquely equipped for guiding this group in approaching the proper balanced synthesis of Torah and worldly values.

It is of great significance that although all identifying information was removed, much of the contents of the haskamah was in fact published in Igros Ukesavim as Letter no. 127. This shows that, in the view of the publishers of Igros Ukesavim, this letter belongs in the Pahad Yitzhak corpus, R. Hutner’s written legacy. To my mind, this indicates that the letter reflects R. Hutner’s authentic position regarding the value of secular studies and R. Hirsch’s approach.

The Story Behind The Haskamah and its Removal

The question remains, why was R. Hutner’s haskamah pulled from some editions of Vistas From Mount Moria? Yosef Levi shared with me an excerpt of the text of his yet to be published biography of his father in which he records the story which I have paraphrased below:[27]

Before the book was published some copies were distributed. Apparently, R. Aharon Kotler received a copy because he approached R. Levi and told him that he should not publish the book because he found some of the passages in the book problematic. R. Levi responded that he would consult with his rabbis. Apparently, R. Kotler shared some written comments with R. Levi because Yosef Levi records that his father reviewed Rabbi Kotler’s comments and found that they concerned only two pages related to studying science. He then decided to go ahead with publishing the book after removing the two pages from the book that R. Kotler saw as problematic.

He then asked his two rabbis, R. Breuer and R. Hutner, whether he should proceed with this plan to publish the book without these pages. R. Breuer told him to continue to publish the book along with the two pages because in his view there was nothing wrong with them. However, R. Hutner, although he agreed with R. Breuer, asked R. Levi to remove his haskamah from the book. He felt the honor of R. Kotler, whom he saw as his Rebbi, demanded that he not publish his endorsement. R. Levi agreed and R. Hutner paid to have his haskamah removed from the book. The way that this book was printed, there were one thousand copies that were bound (which R. Hutner’s haskamah was removed from) and there were another thousand unbound copies that still had R. Hutner’s endorsement. R. Levi asked R. Hutner what he should do with those copies. R. Hutner told him not to remove his haskamah from them. “Ask me again when they are ready to be bound,” he told Levi. Once the first thousand copies were sold and they were ready to bind the second thousand, R. Kotler had already passed away. At this point, R. Hutner instructed Levi to bind the second batch of books with his endorsement. Later, R. Levi was told,[28] many people had called R. Hutner asking him to withdraw his endorsement from the book. With his characteristic wit, R. Hutner told the person who answered the phone (probably his daughter, Rebbetzin Bruriah Hutner-David) to tell these callers that he was unable to take their call as he was taking a course at New York State University.

Conclusion

I believe the context of R. Hutner’s letter and its subsequent removal is of historical significance because it provides the student of history with a hitherto unknown understanding of R. Hutner’s nuanced view of Torah Im Derekh Eretz. It appears that although he supported and advocated for R. Levi bringing a Torah Im Derekh Eretz perspective to those “outside of the Bais Hamedrash,” he chose ultimately not to advocate for this approach formally for the larger American Jewish community. He decided not to publish his endorsement for R. Levi’s book and not to establish a yeshiva high school or college based on the principles of Torah Im Derekh Eretz. Why was R. Hutner’s public position so drastically different from his personal one?

First, and perhaps most significant of all, was R. Aharon Kotler’s role in both the abandonment of the dual-curriculum college as well as the removal of the haskamah should not be underestimated. It is likely that the power and force of R. Kotler’s personality and his Torah-stature prevented R. Hutner from even entertaining the possibility of deviating from his position. Once R. Kotler made his position known, R. Hutner, despite his own view being more amenable to secular studies, was compelled to comply out of his deep respect for R. Kotler, or simply because it would be impossible to succeed at the communal level without his support.

Second, I believe in order to appreciate R. Hutner, one has to understand that in addition to being a talmid hakham, innovative thinker and Rosh Yeshiva, he was a pragmatic leader with an eye towards communal policy. I believe the reason for his choices not to move forward with an American Yeshiva College and not to publish his haskamah has much to do with R. Hutner’s vision for the development of the post-war American Jewish community.

R. Hutner fully believed in the success of a new American Yeshiva community even when it was not at all obvious it would succeed. In America, the Conservative and Reform movements were seen by many as the way of the future. However, R. Hutner remained determined to create a strong and vibrant American Yeshiva community fully dedicated to greatness in Torah and mitzvos.[29] Although it would be an “American” Judaism, different from the European world from which he emerged, it would not be founded upon compromises. I believe this lay at the heart of R. Hutner’s ultimate opposition to a formal synthesis of Torah and secular studies. In R. Hutner’s mind, for the fledgling American Yeshiva community, a dual curriculum would be seen more as a compromise than an ideal.

As historian Zev Eleff has noted, much of the ideological battles in the American Orthodox community during the post-war years can be seen as a debate over what was “authentic Orthodoxy.” R. Hutner was determined to ensure that the newly forged post-war American Jewish community would be an authentic Judaism devoid of compromises. It is likely that in R. Hutner’s view, R. Hirsch’s program of Torah Im Derekh Eretz, although an admirable one, was perceived as more of a balancing act. Just as it was a legitimate and valiant attempt in Frankfurt to bridge the world of the Yeshiva and the outside world, so too in America, it was valuable for those “outside the walls of the Beis Hamidrash.” However, R. Hutner, not just a Rosh Yeshiva but a communal visionary, believed that in order to shape the future of the American Yeshiva community and achieve the creation of an “authentic Orthodoxy,”[30] the face of the community had to be authentically and exclusively Torah-based. If this is correct, unlike R. Ahron Kotler, R. Hutner’s endorsement of a “Torah-only” approach was less of his own personal view and more of a pragmatic vision of what he assessed would effectively capture the hearts and minds of the American Jewish community.

It appears that history has come out in favor of this vision. Against all odds and all critics, the American Yeshiva community has continued to grow by leaps and bounds beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Although the Jewish community is currently in a new era, with its own set of challenges and opportunities, the early growth of the Yeshiva community was vital for American Orthodoxy’s success. Although not a direct heir to the Hirschian Frankfurt educational model, the American Orthodox community has certainly benefited from yeshivas that embraced a dual curriculum model as well. As the American Orthodox Jewish community grew in the 20th century against all odds and predictions, it became clear that in the new world of America, more than one approach can prosper.

Appendix

[1] For biographical information on R. Hutner see R. Dr. Hillel Goldberg, Between Berlin and Slobodka: Jewish Transition Figures From Eastern Europe (Ktav, 1989), pp. 63-87; “Zikhronos,” in R. Yosef Buxbaum (ed.) Sefer Hazikaron Limaran Baal Pahad Yitzhak (Gur Aryeh Institute for Advanced Jewish Scholarship, 1984), pp. 3-66 translated with additions by Rebbitzen Bruriah David and R. Shmuel Kirzner (ed.) An Inner Life: Perspectives on the Legacy of HaRav Yitzchok Hutner zt”l (Gur Aryeh Institute for Advanced Jewish Scholarship, 2024); Yaakov Elman, “Rav Yitzchok Hutner and the Meaning of Hanukkah,” Tablet (December 4, 2015). In Hebrew see Alon Shalev, “Orthodox Theology in the Age of Meaning: The Life and Works of Rabbi Isaac Hutner (Hebrew University Doctoral Dissertation, 2021); Uriel Benar, “Hatifaso shel harav Yitzhak Hutner Vishahruro,” Hamayan Gilyon 61:2, Tevet 5781(Machon Shelomo/Yeshivat Shalavim), pp. 31-47; Shlomo Kiserer, “Hateshuva Bihaguto Shel Harav Yitzhak Hutner,” (Bar Ilan University Doctoral Dissertation, 2008); Yisrael Besser, “Hamahapkhan,” Mishpacha (17 Kislev 5781).

Notwithstanding these works, generally, there has been little biographical material published on R. Hutner. Some may suggest the reason for this is R. Hutner’s general disapproval of biographies. R. Dovid Bashevkin notes in his “Letters of Love and Rebuke From Rav Yitzchok Hutner,” Tablet (October 9, 2016), that R. Hutner laments the often hagiographic nature of rabbinic biographies in an often quoted letter in Pahad Yitzhak, Igros Ukesavim, Letter no. 128 (Gur Aryeh Institute for Advanced Jewish Scholarship, 1981). However, there is evidence that R. Hutner did in fact greatly appreciate the genre of “gedolim biographies.” Zikhronos, p. 88 states, “[R. Hutner] chose [to study] not only complete periodical history, he also [studied] biographical works of the gedolim of the generations.” (translation is my own).

For more on R. Hutner’s groundbreaking work see Steven S. Schwarzschild, “An Introduction to the Thought of R. Isaac Hutner,” Modern Judaism 5:3 (1985), pp. 235-277; R. Dr. Hillel Goldberg, “Rabbi Isaac Hutner: A Synoptic Interpretive Biography,” Tradition 22 (Winter 1987), pp. 18-46; R. Dr. Yaakov Elman, “Autonomy And Its Discontents: A Meditation On Pahad Yitshak,” Tradition 47.2 (Summer 2014), pp. 7-40.

[2] Between Berlin, p. 63.

[3] William Helmreich, The World of the Yeshiva: An Intimate Portrait of Orthodox Jewry (Free Press, 1982), pp. 220-224.

[4] Ibid., p. 35.

[5] Shmuel Avigdor, Mipihem Shel Raboseinu (Bnei Brak, 2007), pp. 458-459. [Hebrew]. The interviews were conducted on 15 Kislev 5725 and 23 Shevat 5727. Translation is my own.

[6] Helmreich, p. 234. Interview conducted on July 9, 1978. It can be noted that although the students at Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin did have secular coursework as part of their high school curriculum, when R. Hutner had the opportunity to found his own yeshiva in Jerusalem, Israel, Yeshivas Pahad Yitzhak, to my knowledge, he never implemented any form of secular studies into the students’ curriculum. However, this may not be completely indicative of R. Hutner’s worldview as much as a practical consideration. The implementation of a dual curriculum in Eretz Yisrael was historically more contentious than in the United States. For example see Yaacov Lupu, “Haredi Opposition to Haredi High-School Yeshivas,” The Floersheimer Institute For Policy Studies (2007) [Hebrew] and Christhard Hoffmann and Daniel R. Schwartz, “Early but Opposed — Supported but Late: Two Berlin Seminaries which Attempted to Move Abroad,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book, 36 (1991), pp. 267-283.

It should be noted that of late, things are beginning to change on that front. See for example the work of Rabbi Yehoshua Pfeffer of the Iyun Institute (Herut Israel Liberty Center) and Rabbi Karmi Gross, Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Derech Chaim to foster greater Haredi involvement in Israeli society which includes more openness to secular studies in Haredi yeshivas.

[7] Between Berlin, p. 78.

[8] Ibid., p. 65.

[9] Dr. David Kranzler and R. Dovid Landseman, Rav Breuer: His Life and His Legacy (Feldheim, 1998), p. 135.

[10] The authors (Ibid.) note that R. Mendel Zaks and R. Aharon Kotler were opposed to the founding of the school.

[11] Helmreich, pp. 46-47. According to the charter application (Petition for American Theological University, pp. 1-10, prepared for The Regents of the University of the State of New York on March 30, 1946) the school would offer a basic liberal arts program “equal to that of other junior colleges chartered by the Regents. The petition also proposed to establish a number of graduate schools, for which a B.A. would be required.

[12] Dr. Shnayer Z. Leiman’s father.

[13] Helmreich, p. 50.

[14] Pahad Yitzhak, Igros Ukesavim, Letter no. 94. Translation adapted from R. Dovid Bashevkin, “Letters of Love and Rebuke.”

[15] It should be noted that here R. Hutner uses the term “Torah Umelakhah” to describe a combination of Torah study and other occupations. This term connotes engagement with the secular from a more pragmatic and practical perspective.

[16] Although the recipient of this letter is not named (as is the case with all of R. Hutner’s responsa in Igros Ukesavim), according to R. Moshe Lieber, it is R. Michoel Ber Weissmandl and the work, which was removed from the letter, was his Min Hameitzar.

Clear proof of this can be seen in Sefer Zikaron (p. 44) which makes explicit reference to a letter R. Hutner wrote to R. Weissmandl. Personal correspondence with Rabbi Moshe Lieber (May-June 2021). For more on R. Weissmandl and his historical role in rescuing Jews from the Holocaust see Avraham Fuchs, Karasi V’Ein Oneh (Jerusalem, 1983) translated in The Unheeded Cry (Artscroll/Mesorah, 1984).

[17] See Yehuda (Leo) Levi, “An Unpublished Responsum on Secular Studies,” Proceedings of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists 1, pp. 106-112. These four responsa were reprinted by Levi in his “Shetei Teshuvos Al Limud chokhmos chizoniyos,” Ha-Ma’ayan 16:3 (1976), pp. 11-16, and in his Sha’arei Talmud Torah (Jerusalem, 1981), pp. 296-301 and in Ha-Pardes 64:8 (May 1990): pp. 9-12. For more see Jacob J. Schacter, “Torah u-Madda Revisited: The Editor’s Introduction,” The Torah Umadda Journal 1 (1989): pp. 1-2, and nn 1-3.

[18] There are some discrepancies between the different publications of these letters. See Marc B. Shapiro, Between The Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy: The Life and Works of Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg (Littman Library, 1999), p. 152n77; Yehuda (Leo) Levi, “Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch-Myth and Fact,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, Vol. 31, no. 3 (Spring 1997), 11; Marc B. Shapiro, “Torah im Derekh Erez in the Shadow of Hitler,” Torah Umadda Journal, Vol. 14, (2006-2007), pp. 85-86,95; my “Hirschian Humanism after the Holocaust,” Seforim Blog (April 2021), footnote 15.

[19] In this work, he refers to some of these gedolim’s statements although without noting the context in which these statements were made. It is unclear if the author was aware of the backstory of these letters at the time he published this work in 1959. See Leo Levi, Vistas From Mount Moria: A Scientist Views Judaism and the World (Gur Aryeh Institute for Advanced Jewish Scholarship, 1959), p. 94.

[20] Haskamos are available here:

על הספר שערי תלמוד תורה לר”י לוי <פתיחות לדעות שונות> – פורום אוצר החכמה (otzar.org). There appears to be some changes made to R. Pinchas Menachem Alter’s haskamah. See below for the original which shows clearly that some text was removed from the printed version.

על הספר שערי תלמוד תורה לר”י לוי <פתיחות לדעות שונות> – פורום אוצר החכמה (otzar.org).

To explain these discrepancies, Yossi Levi (Personal correspondence, May 6, 2024) shared with me that in Yehuda Levi’s (father) archive there exists a correspondence between his father and R. Alter in which R. Alter accepts R. Levi’s comment that his position is more clearly reflected in haskamah that was printed and not the initial written version.

[21] Yehuda Levi, Torah Study: A Survey of Classic Sources on Timely Issues (Feldheim, 1990), p. xxix. This is not the first time R. Hutner was associated with a missing haskamah. See R. Eitam Henkin, “Eiduto shel Harav Hutner Odot Harayah Kook Vihauniversitah Haivrit,” Hamayan 53:3 (Nisan 5773), pp. 61-69 translated in R. Eitam Henkin, Studies in Halakhah and Rabbinic History, (Maggid, 2021) p. 316n16 who notes that Toras Hanazir, R. Hutner’s first work printed in 1936, was subsequently published a number of times missing the haskamah of R. Avraham Yitzhak Kook.

[22] Although he did not write a haskamah which appears in the book, R. Shimon Schwab wrote a very positive review of Shaarei Talmud Torah in which he states it is “a most remarkable work, to say the least. It combines erudition, scholarship, and great reverence for Torah and Gedoley Torah… It would be a great service to the English-speaking public to have this Sefer translated as soon as possible. See R. Shimon Schwab, Mitteilungen (Tishri/Kislev 5743), adapted from the back cover of Torah Study.

[23] The Levi family has an oral tradition of descendancy from the Maharal (Personal Correspondence, Yosef Levi, July 15, 2024).

[24] Yosef Levi believes that the name was penciled in by his father although a signature was clearly meant to be there. This claim is supported by the correction made in pencil (again, presumably made by the author) to R. Breuer’s haskamah.

[25] Shnayer Z. Leiman, “Rabbinic Openness to General Culture,” in Jacob J. Schacter, ed., Judaism’s Encounter with Other Cultures – Rejection or Integration? (Maggid, 2017), pp. 234-248.

[26] R. Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Pentateuch, Genesis 3:24.

[27] Yosef Levi (Email correspondence, May 6, 2024).

[28] Yosef Levi shared that he was told this by his father.

[29] See his “Our Attitude Toward Public Opinion,” Jewish Observer 6 (March 1970): 11-13 where he advocates for a confident “Torah-conscious Jew” who rises above the sway of public opinion.[30] Zev Eleff, Authentically Orthodox (Wayne State University Press, 2020).