A nay bintl briv: Personal Reminiscences of Rabbis Baruch ha-Levi Epstein and Aaron Walkin from the Yiddish Republic of Letters

A nay bintl briv:

Personal Reminiscences of Rabbis Baruch ha-Levi Epstein and Aaron Walkin

from the Yiddish Republic of Letters

Shaul Seidler-Feller

Editor’s note: The present post is part two of a two-part essay. Part one can be found here.

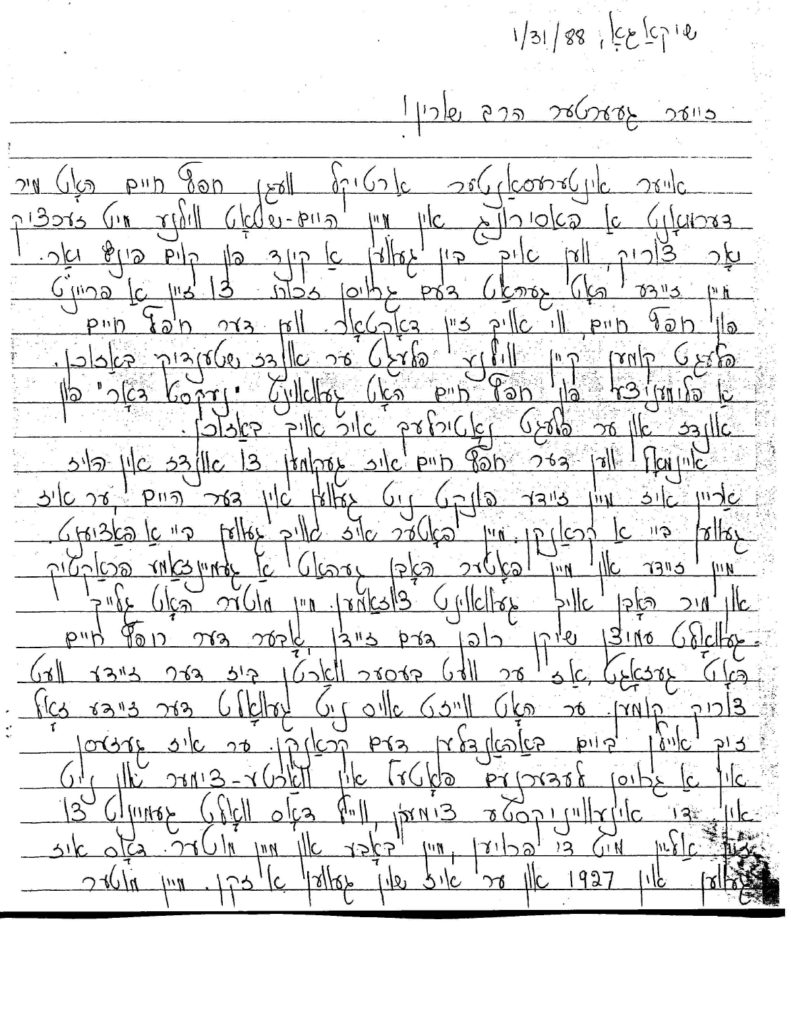

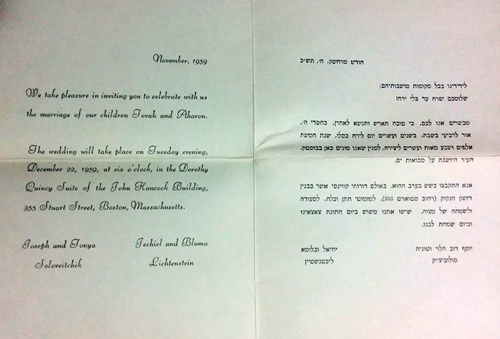

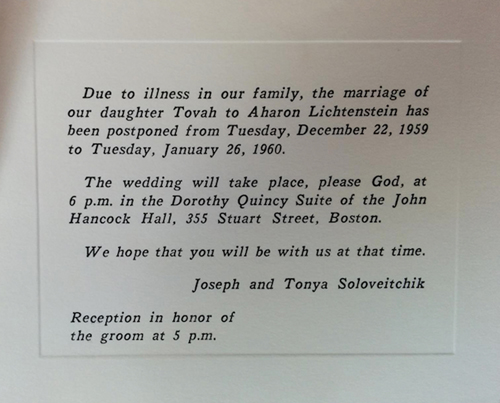

Second Letter

Approximately eight and a half years after his column on the Hafets Hayyim appeared, Rabbi Aaron B. Shurin penned another essay, entitled “The Mistake of the Austrian Emperor” and about the meaning behind the observance of the Three Weeks, which was published 18 Tammuz 5756 (July 5, 1996), a day after they had begun.[1] In the first line, he quoted Rabbi Baruch ha-Levi Epstein (1860–1941/1942) as citing a story about Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I’s (1830–1916) negative response to a group of Hungarian nationalists who wished to establish a day of mourning for the loss of their independence in 1848, using the Jews’ observance of Tish‘ah be-Av as a model.[2] This prompted Simon Paktor to write in:

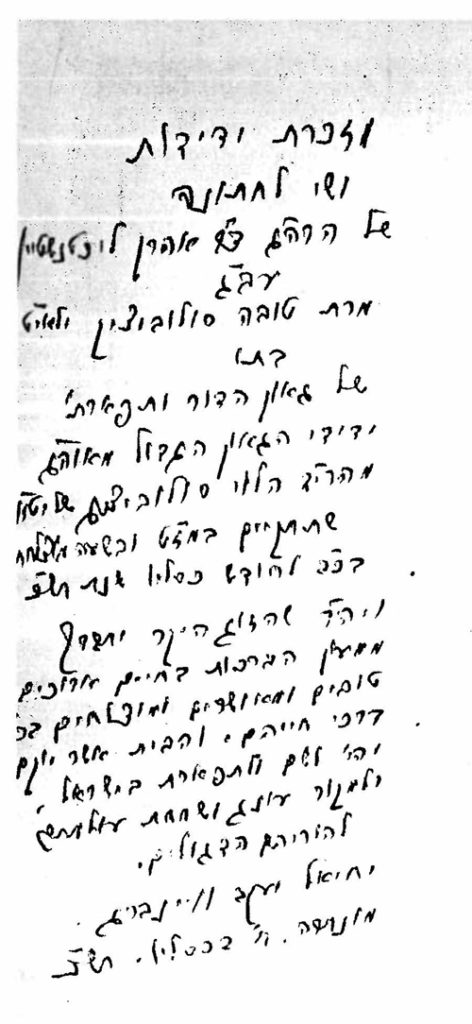

SCHENECTADY 9.5.96.

זייער געערטער און חשובער

.הרב ר״ אהרון בן ציון שוּרין נ״י

עס איז מיר זייער פארדראסיג וואס כ׳האב ניט בעוויזן

צו שרייבן מאמענטאל, און זיך הארציג בעדאנקען פאר

.אייער ארטיקל ״פאָרווערטס״ דעם 5-טן יולי ה.י

ווי געוויינליך ווען די אידישע צייטונג קומט

אן צו מיר, איז עס ביי מיר ווי א גוטער פריינד

וואלט געקומען פון דער אלטער אומפארגעסליכער

..פארשניטענער היים… און מיר ריידן א[וי]ף יידיש

איך האב ממש א ציטער געטאן ווען כ׳האב

אין אייער ארטיקל וועלכן איך לייען שטענדיג מיט דעם

גרעסטן אינטערעס דערזען אין דער ערשטער שוּרה דעם

טייערן נאמען ״הרב ר׳ ברוך עפשטיין (מחבר פון

פירוש ״תורה תמימה״ אויף חומש) דערציילט אין

[3](זיין זכרונות ספר ״מקור ברוּך״ א.א.וו

איך האב געהאט די זכיה צו קענען

אט דעם ״אִיש פֶלֶא״ כבין געווען א פריינד

פון א פינסק-קארלין משפחה וועלכע האט זיך

געיחוס׳ט מיט קרובישאפט. דער פאטער פון דער

פאמיליע האט בעת א שבת׳דיגן וויזיט צוגעטראגן צו מיר

דעם ספר ״מקור ברוך״ און בעוויזן אז ר׳ ברוך

2

ווייזט אן אז אין שׁימל פון ברויט ליגט

דער פאטער אלתר סלוּצקי .PENECiLiN רְפוּאָה ווי

איז געווען א לאַווניק אין שטאט ראַט און די טאכטער האט

געארבעט אין דער יידישער אפטיילונג. אזוי ווי פינסק

האט געהאט א פנקס פון 800 יאר האט זיך זי געהאט די

א מעגליכקייט אויסגעפינען און אנטקעגן קומען ר׳ ברוך עפשטיינס

ביטעס אין די ארכיווע אויסצוזוכן. ער פלעגט זיך שטענדיג

בעדאנקען צו איר דורך שיקן א ״באָמבאניערקע״

דא הייסט עס א באַקס שאקאלאד)… איך)

.מיט טרערן אין די אייגן און מוז א וויילע איבערייסן

.ער האט מיר אויסגעלערנט אן אריטמעטיג פארמוּלע

איך דערמאן זיך ווען כ׳האב שבת נאכן דאוונען אין פינסקער

גרייסער שוּל אראבגעגאנגען צום ברעג פון אונזער

און בעמערקט ר׳ ברוך עפשטיין ז”ל PiNA שיינער טייך

זיצט אויף א באַנק כ׳בין צוגעגאנגען צו עם און געזאגט

״גוט שבת ר׳ ברוּך גום ברוך יהיה״

ער האט געענטפערט ״גם אתם״ און צובייגענדיג צו מיר

געפרעגט ״אפשר האט איר די פאָלקס צייטונג״

(א בונדיסטישע צייטונג וואס איז ארויס אין ווארשע)

(ווען איך האב עס דערציילט א היגן רָב (ניט קיין ראביי

האט ער צו מיר געזאגט יעצט זע איך

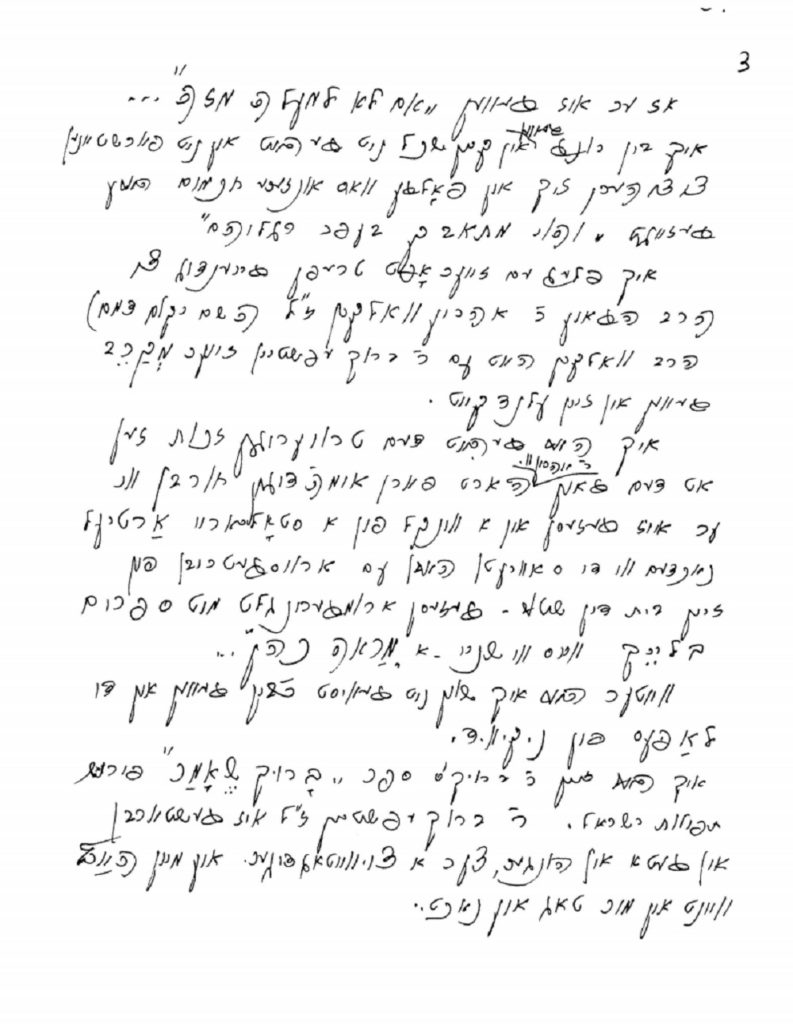

3

…אז ער איז געווען ״אם לא למעלה מזה״

איך בין יונג געווען און קיין שכל ניט געהאט און ניט פארשטאנען

צו צוהערן זיך און פאָלגן וואס אונזערע חכמים האבן

געזאגט ״והוי מתאבק בעפר רגליהם״

איך פלעג עם זייער אָפט טרעפן גייענדיג צו

(הרב הגאון ר׳ אהרון וואלקין ז״ל השם יקום דמם

הרב וואלקין האט עם ר׳ ברוך עפשטיין זייער מְקַרֵב

.געווען אין זיין עלנדקייט

איך האב געהאט דעם טרויעריגן זכות זען

אט דעם גאון ר׳ אהרון וו. הארט פארן אימה׳דיגן חורבן ווי

ער איז געזעסן אין א ווינקל פון א סטאָליאריי אַרטיעל

נאכדעם ווי די סאוויעטן האבן עם ארויסגעטריבן פון

זיין בית דין שטוב. געזעסן ארומגערינגלט מיט ספרים

…בליֵיך ווייס ווי שניי. א ״מַראה כהן״

ווייטער האב איך שוין ניט געווּסט כ׳בין געווען אין די

.לאַפּעס פון נ.ק.וו.ד

איך האב זיין ר׳ ברוּך׳ס ספר ״בָרוּך שֶאָמַר״ פירוּש

תפילות ישראל. ר׳ ברוך עפשטיין ז״ל איז געשטארבן

אין געטא אין הונגער, צער א צוּווייטאגדיגער. און מיין האַרץ

..וויינט אין מיר טאג און נאכט

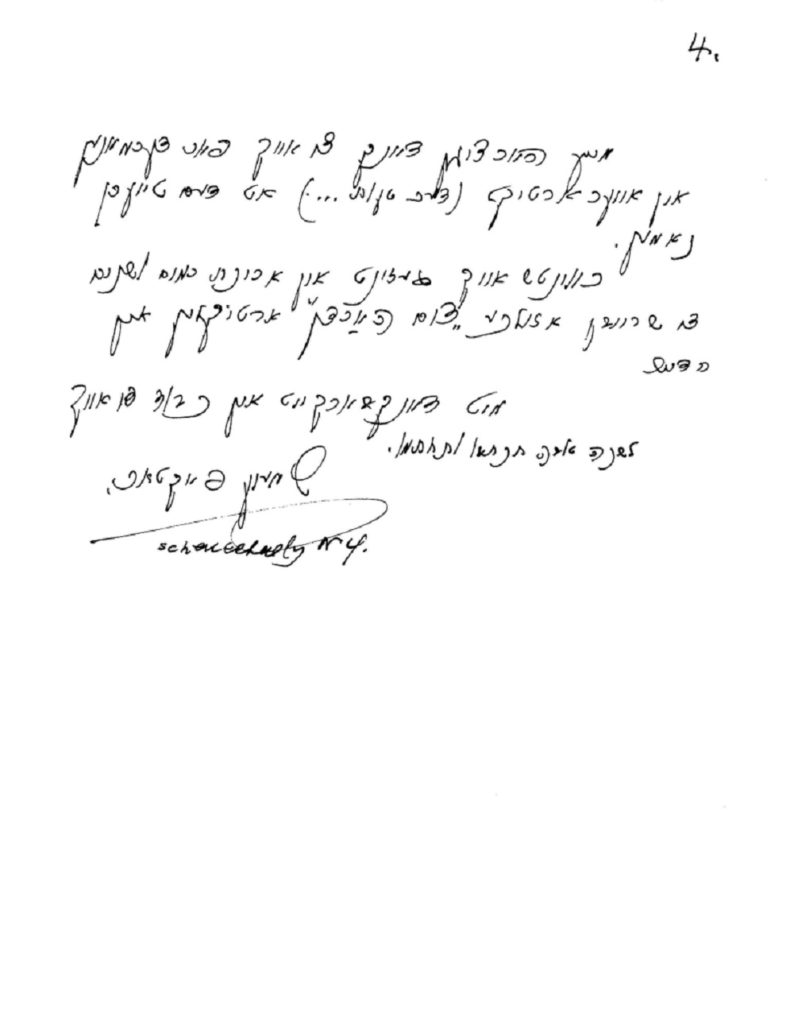

4

מיין הארציגן דאנק צו אייך פאר דערמאנען

אין אייער ארטיקל (דער טעות….) אט דעם טייערן

.נאמען

כווינטש אייך געזונט און אריכת ימים ושנים

צו שרייבן אזעלכע ״צום האַרצן״ ארטיקלען אין

יידיש

מיט דאנקבארקייט און כבוד צו אייך

.לשנה טובה תכתבו ותחתמו

.שמעון פאקטאר

Schenectady NY.

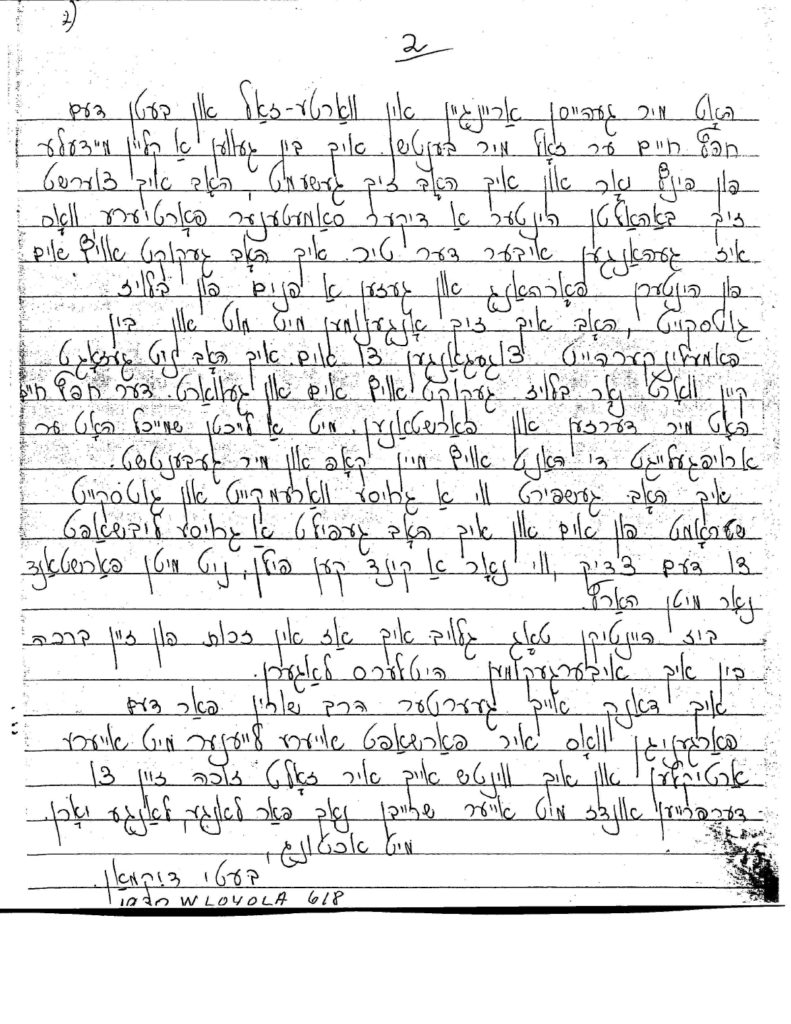

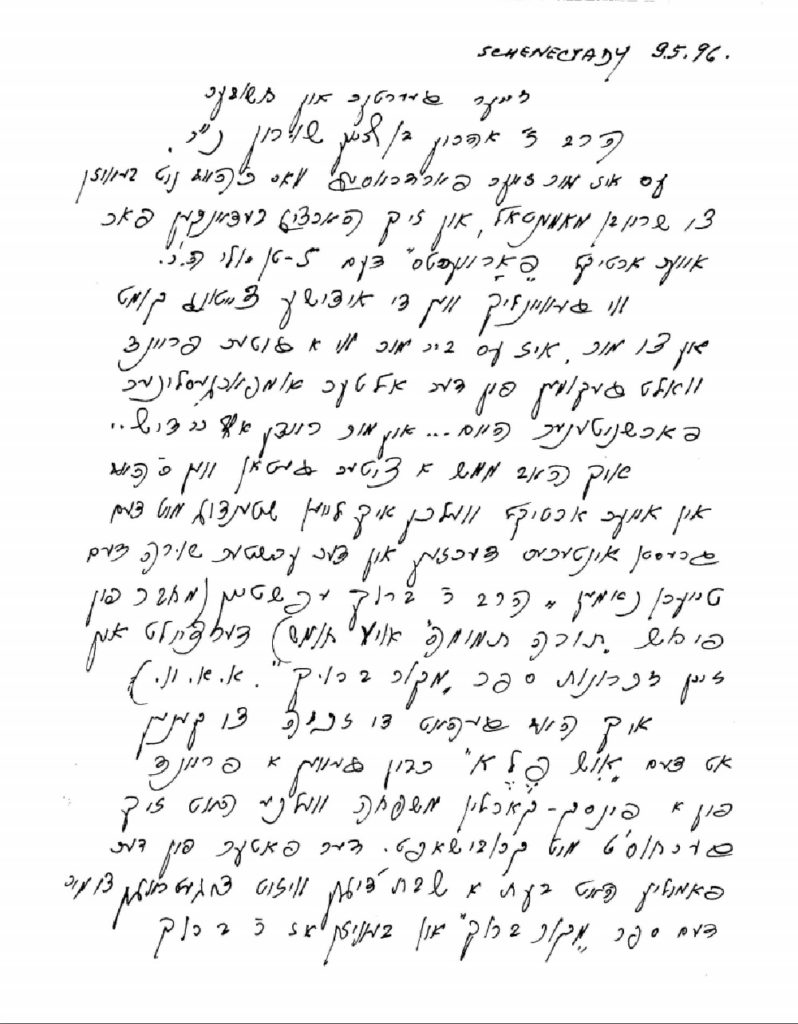

Schenectady 9.5.96

To the highly esteemed and eminent Rabbi Aaron Benzion Shurin, may his light shine,

I am greatly displeased that I did not manage to write immediately to offer my sincere thanks for your column in this year’s July 5th issue of the Forverts.

As is usual when the Yiddish newspaper is delivered, I felt then as if a good friend had arrived from the unforgettable, obliterated old country… and we were having a conversation in Yiddish…

I literally shuddered when I noticed in the first line of your column – which I always read with the greatest interest – the dear name “Rabbi Baruch Epstein (author of the Torah temimah commentary on the Pentateuch) relates in his memoir Mekor barukh,” etc.

I had the good fortune to know that “amazing man.” I was friendly with a family in Pinsk-Karlin that took pride in its kinship with him. The head of the family, during a visit of mine one Sabbath, brought me the book Mekor barukh and showed me that R. Baruch

2

points out that medicine akin to penicillin can be found in moldy bread.[4] The father, Alter Slutzky, was an alderman on the city council, and his daughter worked in its Jewish division.[5] Since Pinsk had a communal register going back 800 years,[6] she had the opportunity to learn of and accommodate R. Baruch Epstein’s requests to search in the archive. He would always thank her by sending a bombonierka (here, we would call it a box of chocolates)…[7] I write this with tears in my eyes and must pause for a moment.

He taught me an arithmetic formula. I remember how one Sabbath, after services in the Great Synagogue of Pinsk,[8] I descended to the banks of our beautiful Pina River and caught sight of R. Baruch Epstein, of blessed memory, sitting on a bench.[9] I approached him and said, “Good Sabbath, R. Baruch – may you, too, be blessed [barukh].”[10] He responded, “The same to you”[11] and, leaning over to me, asked, “Maybe you have a copy of the Folkstsaytung?” (a Bundist newspaper published in Warsaw). When I recounted this story to a local rov (not some non-Orthodox rabbi),[12] he said to me, “Now I see

3

that he was ‘if not even higher than that’[13]…”[14] I was young and foolish and did not realize that I should really listen to and follow that which our Sages taught: “And sit in the dust of their feet.”[15]

I would very often meet him on his way to the ga’on Rabbi Aaron Walkin, of blessed memory (may God avenge their blood). R. Walkin drew quite close to R. Baruch Epstein in his loneliness.

I had the tragic fortune to see that ga’on, R. Aaron W., right before the horrific Holocaust, sitting in a corner of a carpentry workers’ cooperative after the Soviets had banished him from his rabbinic courtroom. He sat surrounded by books, his complexion pale white as snow, like leprosy shown to a priest…[16]

I knew nothing more of him; I was caught in the clutches of the NKVD.

I have R. Baruch’s book Barukh she-amar, a commentary on the Jewish prayers.[17] R. Baruch Epstein, of blessed memory, died in the ghetto a distressed man, starving and suffering. And my heart cries within me day and night…

4

My sincere thanks to you for mentioning in your column (“The Mistake…”) that precious name.

I wish you health and many long days and years so that you might continue writing such “heartwarming” columns in Yiddish.

With gratitude and esteem,

May you be inscribed and sealed for a good year,

Simon Paktor

Schenectady, NY

Although the author of our letter offers precious few details about himself in the body of the document, we know from other sources that he was born to Moishe and Gittel Paktor on January 18, 1913 in Pinsk (then part of Russia, now in Belarus).[18] At the time, Pinsk was one of the most Jewish (percentage-wise) of the major cities in Eastern Europe, with a Jewish population in 1914 of 28,063 out of 38,686 total residents (approximately 72.5%).[19] Presumably because Paktor was young and politically active, the NKVD (Soviet secret police) arrested him toward the beginning of World War II, when Pinsk was occupied by the Red Army, and sent him eastward to a Siberian labor camp, thereby inadvertently saving his life.[20] When he was released, he traveled to Munich where he met and married his first wife, Helen (1925–2019), and the two of them, together with their young son David Leon (b. 1949), immigrated to the United States in 1952.[21] Sometime thereafter the couple divorced, and in 1973 Simon moved to Schenectady to serve as the Ritual Director at Congregation Agudat Achim, a Conservative synagogue (located at 2117 Union Street).[22] There, in 1976, he married Anne Smuckler (1914–2014), whose own husband had passed away three years prior,[23] and continued serving the shul faithfully until his retirement in 1993.[24]

Paktor’s letter, like Dickman’s before it, transports us back in time, providing rare firsthand testimony that sheds light on several aspects of interwar Eastern European rabbinic culture. It deals primarily with the figure of R. Epstein, a brilliant Talmudist and polymath who decided not to enter the rabbinate but instead to support his family as a banker, all the while composing important Torah works in a non-professional capacity.[25] Perhaps the most eclectic of these is Sefer mekor barukh (Vilna, 1928), a multivolume compilation of his novellae and studies in various fields of Jewish scholarship, as well as personal reminiscences about members of his family. Paktor’s letter briefly discusses this book but also, en passant, and intriguingly, references Epstein’s research in the Pinsk Jewish communal archive; could he have been working there on his never-published bilingual (Hebrew and Yiddish) treatise on the history of Pinsk, written in the aftermath of World War I?[26]

Also interesting is Epstein’s request for a copy of the daily Folkstsaytung, not only on account of the paper’s strictly secular orientation – indeed, it, like the Forverts, was published on Shabbat and yom tov[27] – but also because halakhah, according to a number of interpretations, generally disapproves of reading printed matter like newspapers on Shabbat[28] (some would say during the week as well[29]). In apparently seeing nothing wrong with this practice, Epstein was following the example of his maternal uncle and eventual brother-in-law, Rabbi Naphtali Zevi Judah Berlin (Netsiv; 1816–1893), last rosh yeshivah of the famous yeshivah in Volozhin (present-day Vałožyn, Belarus), who, by Epstein’s own account, would regularly peruse a newspaper on Shabbat day.[30]

In addition, the letter opens a window onto the relationship between Epstein and Rabbi Aaron Walkin (alternatively spelled Wolkin; 1865–1941/1942).[31] By the period in question, Epstein had suffered a number of tragedies and personal setbacks: his wife Sophia (Sheyne), the daughter of Eleazar Moses ha-Levi Horowitz (Reb Leyzer Pinsker; 1817–1890), former chief rabbi of Pinsk, had passed away due to influenza in 1899 before the age of 40; the Mutual Credit Society, the large private bank at which Epstein had worked as an officer, closed at the beginning of World War I; and three of his four children were no longer in Pinsk.[32] Though his daughter Fania (Feygl) remained in the city,[33] Epstein was lonely and lived in a hotel.[34] Into this void stepped Walkin, who arrived in Pinsk circa 1923,[35] becoming its chief rabbi in 1933[36] and there growing close to Epstein. The two men had much in common: both had studied at the feet of Netsiv in Volozhin, married around the age of 18, endured great misfortune, visited America but decided to return to Europe, and sympathized (at least somewhat) with the Zionist movement.[37] As Paktor testifies, Epstein, who lived (as of 1930) at 89 Dominikańska (present-day Gor’kogo [renamed by the Soviets]) Street,[38] would often visit Walkin at his home at 71 Dominikańska, a claim confirmed by the latter’s son, Rabbi Samuel David (1900–1979),[39] who refers to Epstein on at least one occasion as yedidi ne’eman beitenu (my friend, a confidante of our household).[40]

Finally, the letter touches directly on the last years of Walkin’s and Epstein’s lives. Shortly after Soviet forces entered Pinsk on September 17, 1939, they banned Hebrew language instruction, abolished the traditional Sabbath and Jewish holidays, and converted the Great Synagogue into a theater.[41] We know from Paktor’s letter and other sources that Walkin, who had been imprisoned by the Russians previously,[42] largely escaped persecution at the hands of the Soviets and even managed to continue performing his rabbinic functions, including scholarly writing, in secret.[43] Epstein, by contrast, was evicted from the hotel in which he had been living and was forced to wander, further weakening him in his old age.[44]

With the Nazi advance into Pinsk on July 4, 1941, an already dire situation was made even more terrifying: Jews were wantonly robbed and beaten, forced to wear Stars of David, ordered to provision the German occupiers, forbidden to leave the city, and detained for labor or ransom. About a month later, on August 5–7, the first Aktion took place, in which the Nazis murdered approximately eight thousand Jewish men outside the city. The following May 1, a ghetto meant to concentrate the approximately twenty thousand remaining Jews was established in the poorest and most crowded part of town; this was later almost completely liquidated in the second Aktion of October 29–November 1, 1942.[45]

What became of Walkin and Epstein during this frightful time? Theories about each man’s demise abound. R. Samuel David refers to his father on several occasions with the acronym reserved for martyrs, H[ashem] y[ikkom] d[amo], following his name.[46] Indeed, at least two Pinsk natives have written that R. Aaron perished together with his flock (presumably in one of the two major Aktionen).[47] Others have hazarded guesses dating his passing to around Passover 1941 or to the summer of 1942.[48] Similarly, as surveyed recently in part by Shemaryah Gershuni, hypotheses regarding Epstein’s date of death range from 1940 to 1942 and, regarding the circumstances of his death, from natural to painful to violent.[49]

In his letter, Paktor himself could not say what had happened to Walkin, while with respect to Epstein, he claimed that he had died in the Pinsk ghetto (he, too, adds Hashem yikkom damam after mentioning them).[50] However, so far as I have been able to ascertain, and as already pointed out by Gershuni, the only eyewitness testimony to have come down to us – that of a nurse named Mila/Michla Ratnowska (b. 1916) who, together with her mother Zlata (1890–1962) and four others, survived the Nazi occupation of Pinsk in hiding – records that both men died (at home) due to illness in the winter of 1941–1942.[51] This timing is corroborated, if only implicitly, by the absence of Walkin and Epstein from the list of over eighteen thousand Jews living in the Pinsk ghetto, drawn up by the Germans “sometime in 1942.”[52] Until additional evidence surfaces, it would seem prudent to accept this as the most reliable version of the events leading up to the passing of these great men, about whom we can say (with a bit of poetic license) that they were “beloved and cherished in their lifetimes, and they never parted, even in death” (II Sam. 1:23).

Conclusion

Like the giants about whom they wrote, Shurin, Dickman, and Paktor have all passed on (in 2012, 2011,[53] and 2003, respectively). How fortunate we are, though, that their memories are preserved for us in this nay (new) bintl briv! Through these simple documents – penned in an age (not too long ago) when people still took the time to correspond thoughtfully with journalists after reading and reflecting on their essays – we are able to reconstruct, if only partially, the lives and deeds of some of the most prominent leaders of Eastern European Jewry in a prewar world now lost.

* I would like to thank Yehuda Geberer for respectfully commenting that he felt I had made a mistake in the first part of this essay, in which I had identified the Chaim Lieberman who assisted Shurin in landing a job at the Forverts as “the famed historian and bibliophile” who lived 1892–1991 (and who often spelled his name Haim Liberman in English). While Geberer is almost certainly correct that Shurin was actually helped by the man of the same name (1890–1963) who, according to his entry in the Leksikon fun forverts shrayber zint 1897, 42-43, worked as a teacher of Yiddish literature and Forverts Yiddish literary critic, I was influenced (apparently unduly so) in my (mis)identification by Yisroel Besser who, in his Mishpacha article (p. 30), writes as follows: “He went to meet the person he considers the greatest Orthodox writer of the century, Chaim Lieberman. Lieberman was a bibliophile, researcher, and historian, who suggested that young Shurin leave him some writings to peruse.”

I also wish to thank Yehudah Zirkind for kindly bringing to my attention another Yiddish-language memoir about the Hafets Hayyim, in which the author, a Radin native, tells a number of interesting stories about the great sage and also notes that he passed away “before reaching his ninety-fourth birthday”; see Abrashka-Kives Rogovski, “Der khofets-khayim in radin,” Oksforder yidish 3 (1995): 193-200, at col. 200.

[1] Aaron B. Shurin, “Der toes fun estraykhishn keyzer,” Forverts (July 5, 1996): 9, 20.

[2] See Baruch ha-Levi Epstein, Sefer mekor barukh, pt. 2 (Vilna: Romm, 1928), 515a-b, citing what he heard from Isaac Hirsch Weiss of Vienna (1815–1905). Epstein refers to the ruler as Franz Joseph II, but in point of fact the relevant Austrian emperor at the time was Franz Joseph I (whose official grand title, interestingly, included the style “King of Jerusalem”).

[3] The quotation of the original Yiddish here is not exact but is certainly close enough.

[4] I have so far been unable to locate the passage referred to.

[5] Jacob-Alter Slutzky was a prominent Orthodox lay leader of the Jewish community of Pinsk who was s/elected to serve on the city council at several points during the interwar period when Pinsk was under Polish rule; see Azriel Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, ed. Mark Jay Mirsky and Moshe Rosman, trans. Faigie Tropper and Moshe Rosman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 469-470, 552-556, 559, 580-581. For the original Hebrew, see Wolf Zeev Rabinowitsch (ed.), Pinsk: sefer edut ve-zikkaron li-kehillat pinsk-karlin, vol. 1, pt. 2 (Tel Aviv; Haifa: Irgun Yotse’ei Pinsk-Karlin bi-Medinat Yisra’el, 1977; also available through the New York Public Library Yizkor Book online portal [accessed August 19, 2019]), using the index. See also Slutzky’s mini-bio in Nachman Tamir (Mirski) (ed.), Pinsk: sefer edut ve-zikkaron li-kehillat pinsk-karlin, vol. 2 (Tel Aviv: Irgun Yotse’ei Pinsk-Karlin bi-Medinat Yisra’el, 1966; also available through the New York Public Library Yizkor Book online portal [accessed August 19, 2019]), 538, where it is noted that Slutzky, like Epstein, was a member of Netsiv’s family (see below) and that he had two daughters, Zhenya and Eve. Based on a daf-ed filed by the former’s sister-in-law, Sonia Goberman (accessed August 19, 2019), it appears that Zhenya was the one who worked in the Jewish division. For Epstein’s endorsement of Slutzky during a campaign season, see “Eyn goldene keyt fun maysim toyvim,” Unzer pinsker lebn 3,42 (102) (October 16, 1936): 5.

[6] An old Pinsker tradition has it that the Jewish community was founded some time in the tenth century; see Benzion Hoffman (ed.), Toyznt yor pinsk (New York: Pinsker Branch 210, Workmen’s Circle, 1941), ix-x (notice the book’s title), and Tamir, Pinsk, 249, 252. Some have averred that an exact date for the start of the community cannot be established at present, given the number of times the Great Synagogue, and any historical documents it may have housed, burned down (on which, see n. 8 below); see, e.g., Saul Mendel ha-Levi Rabinowitsch, “Al pinsk-karlin ve-yosheveihen,” in Judah ha-Levi Levick and Dovberush Yeruchamsohn (eds.), Talpiyyot (me’assef-sifruti) (Berdychiv: Joseph Hayyim Zablinsky, 1895), 7-17, at p. 7. In any event, the current mainstream position holds that it began around 1506, the year in which a privilege issued by Fyodor Ivanovich Yaroslavich, Prince of Pinsk, granted local Jews land for a synagogue and cemetery in perpetuity; see Mordechai Nadav, The Jews of Pinsk, 1506 to 1880, ed. Mark Jay Mirsky and Moshe Rosman, trans. Moshe Rosman and Faigie Tropper (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 13-14.

[7] For a similar story, see Hillel Seidman, “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein – pinsk,” in Isaac Lewin (ed.), Elleh ezkerah: osef toledot kedoshei [5]700-[5]705, vol. 1 (New York: Research Institute of Religious Jewry, Inc., 1956), 142-149, at p. 145; reprinted with some variations in Seidman’s Ishim she-hikkarti: demuyyot me-avar karov be-mizrah eiropah (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1970), 108-116, at p. 111. Relatedly, see the Rosh Hashanah greetings sent to Epstein by the typesetters and printers of the Pinsker vort 2,40 (86) (September 30, 1932): 1, and of ibid. 3,38 (138) (September 20, 1933): 1.

[8] For some of the turbulent history of the Great Synagogue of Pinsk, which fell victim to fires on multiple occasions, see Nadav, The Jews of Pinsk, 1506 to 1880, 463-465; Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 217-220, 300-301, 463, 648, 656; and Tamir, Pinsk, 249-252. For photographs of the synagogue, see here and here (accessed August 19, 2019). For a map of Pinsk from 1864 illustrating the location of the Great Synagogue, see Hoffman, Toyznt yor pinsk, 88-89 (in Yiddish), and Nadav, The Jews of Pinsk, 1506 to 1880, 498-499 (in English). For later maps of Jewish Pinsk, see Hoffman, Toyznt yor pinsk, 232-233, and Tamir, Pinsk, foldout preceding p. 97.

[9] Epstein generally prayed not in the Great Synagogue but in the Pinsker Kloyz, a beit midrash with a firmly mitnaggedic orientation. Ze’ev Rabinowitsch reports that, “in years past, it was said that the walls of the Pinsker Kloyz do not give out in deference to R. Baruch Epstein…” (“Akhsanye shel toyre,” in Tamir, Pinsk, 264). See also Rabinowitsch, Pinsk, 412.

[10] See Gen. 27:33.

[11] In Yiddish, one appropriate response to a greeting like gut shabes! is gam atem!, using the plural atem even when only one person is being addressed. See Sol Steinmetz, Dictionary of Jewish Usage: A Guide to the Use of Jewish Terms (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005), 53.

[12] American Yiddish will often distinguish between Orthodox and non-Orthodox (particularly Reform) rabbis by referring to the former as rov/rabonim (singular/plural) and the latter as rabay/rabays (singular/plural). As essentially transliterations from the English, these terms for non-Orthodox rabbis are usually intended somewhat derogatorily in the mouths of frum Yiddish speakers.

[13] Oyb nisht nokh hekher or, as the phrase appears here in Hebrew, Im lo le-ma‘lah mi-zeh, is the title of a short story by the famous Yiddish and Hebrew classicist I.L. Peretz (1852–1915) about a Litvak who refuses to believe that the Nemirover Rebbe (a fictional character probably based on Rabbi Nathan Sternharz of Niemirów [1780–1845]) ascends on High during the annual period of selihot, as his Hasidim claim he does, instead of coming to the synagogue. Determined to find out where the Rebbe disappears to, he hides under the Rebbe’s bed one night and is amazed to discover that the Rebbe wakes early in the morning, dresses as a Polish peasant, and goes out to the forest to chop firewood for poor bedridden Jewish widows. He thereupon decides to join the Rebbe’s Hasidim, and from then on whenever anyone claims that the Rebbe flies up to Heaven to petition on behalf of his flock before Rosh Hashanah, this Litvak-turned-Hasid responds, “If not even higher than that.”

The story was first published in Yiddish in 1900 as “Oyb nisht nokh hekher! A khsidishe ertseylung,” Der yud 2,1 (January 11, 1900): 12-13. The following year, it appeared, in the author’s own Hebrew adaptation, as “Im lo le-ma‘lah mi-zeh,” Ha-dor 1,17 (1901): 207-211; for the Hebrew text, see here (accessed August 19, 2019). For editions using modern Yiddish orthography, see here and here (accessed August 19, 2019). For side-by-side Yiddish with English translation, see “Oyb nisht nokh hekher/And Maybe Even Higher,” in Itche Goldberg and Eli Katz (eds.), Selected Stories: Bilingual Edition, trans. Eli Katz (New York: Zhitlowsky Foundation for Jewish Culture, 1991), 270-281. For extensive discussions of the story’s subversive messages, historical sources, and inspirations, see Menashe Unger, “Mekoyrim fun peretses folkstimlekhe geshikhtn,” Yidishe kultur 7,3-4 (March–April 1945): 54-59, at pp. 56-57; Samuel Niger, Y.l. perets: zayn lebn, zayn firndike perzenlekhkeyt, zayne hebreishe un yidishe shriftn, zayn virkung (Buenos Aires: Confederacion pro Cultura Judia, 1952), 286-289; and Nicham Ross, Margalit temunah ba-hol: y.l. perets u-ma‘asiyyot hasidim (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2013), 17-83 (ch. 2).

In our context, the phrase is deployed by Paktor’s rabbinic interlocutor to express his realization that Epstein was even greater than he had originally thought.

[14] Paktor apparently also shared this story about Epstein and the Folkstsaytung with Mark Jay Mirsky; see the latter’s introduction to Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, xxix-xxx.

[15] mAvot 1:4.

[16] The Hebrew phrase deployed here is mar’eh kohen, a reference to the requirement that those afflicted with biblical tsara‘at must consult with a priest before the healing/atonement process can move forward (see Lev. 13). The expression, as used by Paktor, does double-duty by playing on the title of the well-known piyyut recited on Yom Kippur, which refers to the priest’s (radiant) appearance, not that of the biblical skin disease.

[17] Barukh she-amar was the last book Epstein printed before he passed away. It originally appeared in Pinsk in 1939 (publisher: Drukarnia Wolowełskiego), but, according to Aaron Z. Tarshish, Rabbi barukh ha-levi epstein[,] ba‘al “torah temimah” (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1967), 189, even though the work achieved great popularity within the city, it did not spread beyond. Epstein sent a single copy to the famous Strashun Library in Vilna, which then passed it on to YIVO, and the latter institution transferred it to its headquarters in New York (see the online catalog record for this copy here [accessed August 19, 2019]). This, then, was apparently the only exemplar of the book to survive the war, and when it was discovered at YIVO some time thereafter, it was used to print the photo-offset reproduction published in Tel Aviv in three parts: vol. 1 on the haggadah (1965), vol. 2 on Pirkei avot (1965), and vol. 3 on the siddur itself (1968). (For a slightly different account of Barukh she-amar’s original publication and rediscovery after the war, see Seidman, “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein,” 148. Based on a helpful personal communication from Lyudmila Sholokhova, Director of the YIVO Library, it would appear that Tarshish’s version of the story is the more accurate one.)

I assume that Paktor owned a copy of the Tel Aviv reprint, not the original Pinsk edition.

[18] See the obituary for Rev. Simon Paktor published in the Albany Times Union (March 2–3, 2003), available here (accessed August 19, 2019).

Franz J. Beranek, in his Das Pinsker Jiddisch und seine Stellung im gesamtjiddischen Sprachraum (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1958), discusses certain distinctive features of the dialect of Yiddish spoken in Pinsk. Upon examination of our letter, we find some of the markers of this litvish (Northeastern Yiddish) dialect reflected in such forms as eygn (eyes; see p. 33, §38, 1), greyser (large; see p. 25, §26), arobgegangen (descended; see p. 53, §48, 2a), em (him; see p. 21, §18, 1), etc. (I suspect that his use of the forms idishe [Jewish/Yiddish], reydn [to speak], and fardrosig/hartsig/shtendig/etc. [displeased/sincerely/always/etc.], instead of the expected yidishe, redn, and fardrosik/harstik/shtendik/etc., is the result of Paktor following common journalistic orthographic conventions and is not reflective of his actual pronunciation of those words.) (For a recent look at Beranek’s relationship with some of his Yiddish scholarly contemporaries, see Kalman Weiser, “‘One of Hitler’s Professors’: Max Weinreich and Solomon Birnbaum confront Franz Beranek,” Jewish Quarterly Review 108,1 [2018]: 106-124.)

[19] See Mordechai Nadav, “Pinsk,” in Shmuel Spector (ed.), Pinkas ha-kehillot: polin, vol. 5 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1990), 276-299, at p. 276 (available in English translation here [accessed August 19, 2019]). See also Dov Levin, Tekufah be-sograyim, 1939–1941: temurot be-hayyei ha-yehudim, ba-ezorim she-suppehu li-berit-ha-mo‘atsot bi-tehillat milhemet ha-olam ha-sheniyyah (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1980), 26, for a chart comparing the populations of cities in eastern Poland in 1931.

[20] See the aforementioned obituary for Paktor published in the Albany Times Union. On NKVD activity in Pinsk during the Soviet occupation, see Pesah Pakacz, “Shilton ha-soviyyetim be-pinsk,” in Tamir, Pinsk, 315-320, at pp. 317-320, and Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 639-650. On NKVD activity among occupied Polish Jewry in general, see Yosef Litvak, Pelitim yehudim mi-polin bi-berit ha-mo‘atsot[,] 1939–1946 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Tel Aviv: Ghetto Fighters’ House; Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1988), 118-156. As noted by Eliyana R. Adler, the similar situation of Baltic Jews exiled to the east by the Soviets demonstrates that had they not suffered that fate, they most likely would have fallen victim to the Nazis when the latter invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941; see her “Exile and Survival: Lithuanian Jewish Deportees in the Soviet Union,” in Michal Ben Ya’akov, Gershon Greenberg, and Sigalit Rosmarin (eds.), Ha-kayits ha-nora ha-hu…: 70 shanah le-hashmadat ha-kehillot ha-yehudiyyot be-arei ha-sadeh be-lita: historiyyah, hagut, re’aliyyah (Jerusalem: Efrata College Publications, 2013), xxvii-xlix, at pp. xlv-xlvi.

[21] See the Holocaust remembrance seminar announcement published in the Clifton Journal (October 30, 2015), p. 36 (available here [accessed August 19, 2019]; make sure to click “View Details”). The Air Passenger Manifest recording the Paktors’ arrival in New York, available to subscribers through the MyHeritage database (accessed June 20, 2019), is dated May 19, 1952; curiously, it lists Simon’s wife’s name as Sabina.

[22] According to Michael C. Duke, “Historian Is CBY Scholar In Residence, Oct. 8–10,” Jewish Herald-Voice (October 7, 2010) (accessed August 19, 2019), Paktor was trained as a rabbi. While I could find no direct corroborating evidence for this claim elsewhere, it is true that he is sometimes referred to in writing with the title “Reverend.” His work at the shul, for which he came to be well loved and respected, included serving as cantor and Torah reader, running the daily minyanim, preparing youth for their bar and bat mitzvahs, and even teaching Yiddish classes; Stephen M. Berk, Year of Crisis, Year of Hope: Russian Jewry and the Pogroms of 1881–1882 (Westport, CN; London: Greenwood Press, 1985), xv, credits Paktor with introducing him to the world of Yiddish scholarship. See also the aforementioned obituary in the Albany Times Union and the above article by Duke. I thank Robert Kasman, Stephen M. Berk, and Mendel Siegel for the information they provided me on Paktor’s life and service to the shul in personal communications.

[23] See the obituary for Anne Paktor published here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[24] Henry Skoburn, The Agudat Achim Chronicle: Commemorating 120 Years[,] 1892–2012 (Schenectady: Congregation Agudat Achim, 2012), 10, 12.

[25] The only book-length biography of Epstein is Tarshish’s (above, n. 17), though, as noted by Eitam Henkin, “Perakim be-toledot ba‘al arukh ha-shulhan: mishpahto ve-tse’etsa’av,” Yeshurun 27 (2012): 879-895, at p. 879, this work is in need of a thorough update that takes a scholarly-critical approach and considers the abundant literature on Epstein and his oeuvre that has appeared over the past fifty-plus years. For a shorter essay on Epstein’s life, see Seidman’s “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein” (above, n. 7). And for a famous photograph of Epstein in his younger years, see Hoffman, Toyznt yor pinsk, 335; reproduced (seemingly with modifications) as the frontispiece of Tarshish’s biography and in Zvi Kaplan, “Hiddushim ba-halakhah shel gedolei pinsk ve-karlin,” in Rabinowitsch, Pinsk, 367-406, at p. 393. (I find it hard to believe that the person in the portrait accompanying the Epstein mini-biography printed in Tamir, Pinsk, 489-491, is actually him but would be happy to be corrected.)

[26] See Baruch ha-Levi Epstein, Sefer mekor barukh, introduction (Vilna: Romm, 1928), 2 n. 1.

[27] The Folkstsaytung (People’s Paper) was the official organ of the General Jewish Workers Union in Poland, also known as the Bund. As such, it espoused a secularist, socialist Weltanschauung and polemicized against Communists, Zionists, and Orthodox Jews, among others. In addition to covering politics and workers’ issues, the paper devoted space to science and technology, sports, culture, and (Jewish and non-Jewish) literature. At its height in 1935, the Folkstsaytung had an approximate circulation of eighteen thousand. See Jacob Shalom Hertz, “‘Folkstsaytung’ 1918–1939,” in David Flinker, Mordechai Tsanin, Shalom Rosenfeld et al. (eds.), Di yidishe prese vos iz geven (Tel Aviv: Veltfarband fun di Yidishe Zhurnalistn, 1975), 151-169, and Boris Kotlerman, “Folks-tsaytung,” trans. I. Michael Aronson, in the digitized YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (accessed August 19, 2019).

According to Seidman, “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein,” 144-145:

[Epstein] had an expansive [intellectual] horizon. He was interested in and familiar with all that was happening in the world. He read Russian and German newspapers. He also visited Vienna and Berlin in the ’20s, meeting with scholars and intellectuals there, and maintained an epistolary correspondence with the towering Jewish figures of the generation. When they visited Pinsk, he would host them. In 1914, Rabbi Hayyim Soloveichik visited Pinsk and stayed with Rabbi Baruch Epstein for Shabbat.

In addition to regularly reading the paper, Epstein also contributed to a number of (rabbinic and general Jewish) periodicals, including Havatselet, Yagdil torah, Ha-levanon, Ha-maggid, Ha-melits, and Ha-pardes; see Baruch ha-Levi Epstein, Sefer mekor barukh, pt. 3 (Vilna: Romm, 1928), 701b, and Shemaryah Gershuni, “Rabbi barukh epstein – ba‘al ha-torah temimah: beirur nesibbot petirato,” Yeshurun 29 (2013): 885-892, at pp. 886 n. 13, 889 n. 25. He even wrote a weekly column on the parashah for the Pinsker shtime; see Seidman, “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein,” 145, 148-149. While I have not examined issues of the Pinsker shtime, I know that Epstein’s parashah columns in a different local paper, Pinsker vort, were entitled Fun gebentshtn kval (=Mi-makor barukh); see the announcement in the February 20, 1931 edition, p. 1.

[28] For a summary of some of the halakhic literature on the topic and a defense (in most cases) of the widespread contemporary disregard of this prohibition, see Eitam Henkin, “Keri’at divrei defus be-shabbat be-yameineu le-or din shetarei hedyotot,” Melilot 3 (2010): 49-63 (the pagination in the printed version is slightly different from that of what I presume to be the prepublication copy available on Henkin’s website).

[29] Indeed, the Hafets Hayyim was particularly vociferous in his opposition to the practice of many of his contemporaries to regularly read newspapers, not only because of their often-improper content (heresy, scoffing, leshon ha-ra, licentiousness, etc.), but also due to the drain on one’s time involved in their consumption. See, e.g., Israel Meir ha-Kohen, Kunteres zekhor le-miryam (Piotrków: Hanokh Henekh Fallman, 1925), 8b; Aryeh Leib Poupko, Mikhtevei ha-rav hafets hayyim z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah]: korot hayyav, derakhav, nimmukav ve-sihotav, 1st ed. (Warsaw: B. Liebeskind, 1937), 96-98 (second pagination; no. 42); ibid., 42-43 (third pagination; par. 82); idem, Mikhtevei ha-rav hafets hayyim z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah], ed. S. Artsi, 2 vols. (Bnei Brak: n.p., 1986), 2:157-158. Relatedly, see also idem, Mikhtevei, 1st ed., 27-29 (second pagination; no. 9). It is clear, however, that the Hafets Hayyim was, at times, exposed to periodical literature; for a letter he sent to the Haredi paper Kol ya‘akov, responding to an earlier issue thereof, see idem, Mikhtevei, ed. S. Artsi, 1:297-298 (no. 122).

[30] See Baruch ha-Levi Epstein, Sefer mekor barukh, pt. 4 (Vilna: Romm, 1928), 895b, 897b-898a. Epstein’s report about his uncle’s behavior in this connection has aroused a good deal of controversy, as discussed by, e.g., Eliezer Brodt, “The Netziv, Reading Newspapers on Shabbos & Censorship,” Seforim Blog, pt. 1 (March 5, 2014) and pt. 2 (April 29, 2015). Like Brodt, Marc B. Shapiro, “Clarifications of Previous Posts,” Seforim Blog (January 16, 2008) (accessed August 19, 2019), believes that one can rely upon this account. On the general question of the historical accuracy of Sefer mekor barukh, see, e.g., Eitam Henkin, “R. yehi’el mikhl epstein ve-ha-‘tsemah tsedek’ ba-adashat ha-sefer ‘mekor barukh’,” Alonei mamre 123 (Winter 2011): 189-215, and Moshe Maimon, “Od be-inyan ba‘al ha-torah temimah u-sefarav,” Kovets ets hayyim 12,1 (2018): 409-420 (among many others).

[31] Probably the two most authoritative biographies of Walkin to date are that appended to the beginning of the second volume of the New York, 1951 photo-offset edition of his responsa, Sefer she’elot u-teshuvot zekan aharon, composed by his son, Rabbi Samuel David (on whom, see below), and entitled “Toledot maran ha-ga’on ha-mehabber z[ekher] ts[addik] v[e-]k[adosh] l[i-berakhah]”; and Hillel Seidman, “Ha-rav r. aharon walkin – pinsk,” in Lewin, Elleh ezkerah, 64-71; reprinted with some variations in Seidman’s Ishim she-hikkarti, 20-28. Eliezer Katzman used these two sources in compiling much of his own profile of Walkin – “Ne‘imut ha-torah: ha-g[a’on] r[av] aharon walkin z[ekher] ts[addik] v[e-]k[adosh] l[i-berakhah,] a[v] b[eit] d[in] pinsk[,] ba‘al beit aharon, zekan aharon v[e-]ku[llei],” Yeshurun 11 (2002): 891-904; 12 (2003): 727-739 – but added some material not found in either. (It seems that unacknowledged verbatim use was made of Seidman’s and/or Katzman’s work in the Walkin biography printed in Daniel Bitton’s editions of Sefer beit aharon on Bava kamma [Jerusalem: Mekhon ha-Ma’or, 2003] and of Sefer hoshen aharon [Jerusalem: Mekhon ha-Ma’or, 2005].) For additional appreciations of Walkin’s Torah, see Kaplan, “Hiddushim ba-halakhah,” 399-406, an earlier version of which had appeared as “Ba‘al ha-‘battim’,” Ha-tsofeh 10159 (June 24, 1966): 5, 7; and of his religious persona, see the excerpt from Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s letter to R. Samuel David, dated 8 Shevat [5]712 (February 4, 1952) and printed at the foot of the introduction to Aaron Walkin, Sefer beit aharon al massekhet gittin, 2nd ed. (New York: S. Walkin, 1955).

For photographs of Walkin, see Anon., “Shlukhim fun agudes yisroel shoyn do,” Yidishes tageblat (December 11, 1913): 8; Anon., “Visiting Rabbis Explain International Jewish Union,” The Pittsburg [sic] Press (January 27, 1914): 3; Anon., “Noted European Rabbis Greeted by Orthodox Jews of Greater Boston,” The Boston Post (February 7, 1914): 16; Kaplan, “Hiddushim ba-halakhah,” 399; Moshe Rosman, “Pinsk,” in the digitized YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (accessed August 19, 2019); Marc B. Shapiro, “A Tale of Two Lost Archives,” Seforim Blog (August 12, 2008) (accessed August 19, 2019); the Jewish Pinsk memorial page here (accessed August 19, 2019) (Walkin is leading the Agudah procession); and David Zaretsky, “Rabbah ha-aharon shel pinsk: le-hofa‘ato me-hadash shel ha-sefer sh[e’elot] u-t[eshuvot] ‘zekan aharon’,” in Zikhram li-berakhah: ge’onei ha-dorot ve-ishei segullah (Israel: n.p., 2015?), 33-39.

[32] See Jacob Goldman’s obituary for Sophia Epstein, entitled “Allon bakhut,” in Ha-tsefirah 26,60 (March 24, 1899): 293. See also the report issued by Aaron Tänzer, “Von Brest-Litowsk nach Pinsk,” Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 80,1 (January 7, 1916): 6-10, at p. 9, in which he mentions Epstein’s widowhood and the bank closure. Of Epstein’s four children – Cecilia (Tsile), Meir, Eleazar Moses, and Fania – Tänzer makes specific reference only to the last, suggesting that the other three were no longer in Pinsk by that point. Indeed, we know that Cecilia’s husband Nathan (Nahum) Bakstansky (Bakst) arrived at Ellis Island in 1907 (see his Geni record here [accessed August 19, 2019]); that they and their children Aaron and Jacob were registered voters as of 1924 (see Anon., “List of Registered Voters for the Year 1924: Borough of Brooklyn—Sixteenth Assembly District,” The City Record [October 16, 1924]: 2); and that Cecilia is registered as the copyright holder for the New York, 1928 edition of her father’s Torah temimah (see Anon., Catalogue of Copyright Entries: Part 1, Group 1 […] for the Year 1929 [Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1930], 1825-1826). In addition, according to family records made available to Henkin, Eleazar Moses had moved to Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg, Russia) (see the corrections appended to the online version of his aforementioned article, “Perakim be-toledot”). And if Seidman is correct that one of Epstein’s sons wound up working as a physician in New York (see the Ishim she-hikkarti version of his article, p. 110), that may mean Meir, like Cecilia, made it to America as well. (I find the idea that Meir and Fania died in their youth, as reported on Henkin’s website, difficult to believe, considering that Tänzer makes no mention of this in 1916, based on a visit to Pinsk in November 1915; see also next note. But until additional information becomes available, this will be virtually impossible to definitively reject [or accept].) In this connection, see also Maimon, “Od be-inyan,” 418-419, for an interesting interpretation of a passage in Sefer mekor barukh, pt. 4.

[33] Fania was instrumental in founding a Jewish girls’ gymnasium in Pinsk in the fall of 1915, reportedly with her father’s approval. See Tänzer, “Von Brest-Litowsk,” 9, and Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 34, 183, 350-351, 596-597; see also Tamir, Pinsk, 510-512. She apparently passed away during World War II, given that she (like her father) is listed among the martyrs of Pinsk in Tamir, Pinsk, 627. (It is unclear to me whether or not the Meir cited there was R. Baruch’s son.)

[34] As of Tänzer’s visit, it seems that Fania attended to the needs of her father’s house (“Von Brest-Litowsk,” 9). Tarshish notes, however, that at a certain point he began living in a local hotel, whose proprietors took care of him honorably and with dedication (Rabbi, 127; though cf. below, n. 38). Seidman adds that he ate his meals at a restaurant in the city while living in the hotel (“Ha-rav r. barukh epstein,” 144). Three hotels, all under Jewish ownership, are named in the “List of Subscribers of the Telephone Network of the Postal and Telegraph Directorate in Wilno in 1939” (select p. 52 from the drop-down menu) (accessed August 19, 2019). I have not been able to ascertain at which of these three Epstein lived.

[35] See Kaplan, “Hiddushim ba-halakhah,” 399; see also Ben-Mem, “Ha-ga’on r. aharon walkin z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah],” in Tamir, Pinsk, 499-500, who notes that Walkin eulogized Rabbi Jacob Mazeh of Moscow (1859–1924) within the first year of his arrival in the city. Cf. the introduction to Aaron Walkin, Sefer beit aharon al massekhet bava kamma (Vilna: Shraga Feivel Garber, 1923), which the author signed (seemingly in 1923) while living in the Jewish community of Amtshislav (present-day Mscisłaŭ, Belarus). Cf. also Anon., “Horav r. arn wolkin vegn zayn raykher lebns-fargangenheyt,” Unzer grodner ekspres 2,79 (April 2, 1929): 1, the second part of an interview with Walkin, which claims that he emigrated from Russia in 1922; as well as Aaron B. Shurin, “Tsvey shayles utshuves sforim fun letstn pinsker rov,” Forverts (October 14, 1977): 3, 6, at p. 3, who writes that Walkin came to Pinsk in 1924. (On his way from Russia to Poland, he had an extended stopover in Danzig; see M. Lyubart, “Vegn yidishn lebn in danzig,” Pinsker vort 2,11 [57] [March 11, 1932]: 5.)

[36] See Anon., “Horav walkin oysgeveylt als rov fun pinsker kehile,” Pinsker vort 3,32 (132) (August 11, 1933): 6, and Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 571. Cf. Ben-Mem, “Ha-ga’on r. aharon walkin,” 500, who gives the date as [5]688 (1927–1928). (His election to the rabbinate of neighboring Karlin had taken place over a year earlier; see Anon., “Horav walkin als karliner rov,” Pinsker vort 2,6 [52] [February 5, 1932]: 6.)

Relatedly, see Dov Rabin (ed.), Grodnah-Grodne (Jerusalem: Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora, 1973; also available through the New York Public Library Yizkor Book online portal [accessed August 19, 2019]), col. 352, on the brief period in 1929 when the Jews of Grodno – then part of Poland but now in Belarus – considered appointing Walkin as the chief rabbi of their community (an episode that deserves fuller historiographic exploration); see also Anon., “Kehile-rat geg[n] horav wolkin,” Unzer grodner ekspres 2,88 (April 12, 1929): 15.

[37] For Epstein, see Tarshish, Rabbi, 70-80 (relationship with Netsiv), 84-89 (marriage at approx. 18), 120-126 (visit to America), 134-135, 148-149 (Zionist sympathies) (all based primarily on passages in Sefer mekor barukh); Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 536 (Zionist sympathies); and Gershuni, “Rabbi barukh epstein,” 890-892 (visit to America). For Walkin, see his undated introduction to Sefer beit aharon al massekhet bava kamma (visit to America); the postscript to his undated introduction to the commentary Saviv li-yere’av, vol. 1 (Pinsk: Drukarnia Wolowełskiego, 1935), and the wishes of nehamah printed in Dos naye pinsker vort 7,51 (356) (December 3, 1937): 6 (personal misfortune); his son’s “Toledot maran ha-ga’on ha-mehabber” (relationship with Netsiv, marriage at approx. 18, visit to America); and Ben-Mem, “Ha-ga’on r. aharon walkin,” 500, and Rabin, Grodnah-Grodne, col. 352 (Zionist sympathies). Relatedly, Walkin’s son Hayyim married the daughter of Rabbi Abraham Isaac ha-Kohen Kook (1865–1935); see the mazl tov wishes on the occasion of their engagement printed in Do’ar ha-yom 8,182 (April 28, 1926): 1, and in Ha-arets 9,2041 (May 2, 1926): 4.

For a lecture delivered in Yiddish during Walkin’s visit to the United States, undertaken December 1913–February 1914 in order to help establish Agudath Israel in America, see Aaron Walkin, Di printsipen un tsveke fun agudes yisroel: fortrog gehalten fir amerikaner idn (New York: Office of Agudath Israel, n.d.). (During his trip, Walkin visited the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary at 156 Henry Street; for his comparison of the yeshivah with that of Volozhin [!], see Anon., “Agudes yisroel shlukhim in yeshives rabeynu yitskhok elkhonen,” Der morgen zhurnal [December 24, 1913]: 4. Cf. Anon., “Horav wolkin begaystert fun idishe anshtalten in amerika,” Der morgen zhurnal [January 13, 1914]: 4.)

Tragically, Epstein and Walkin shared another fate: each printed a sefer in 1939 in Pinsk, only one copy of which survived the war and was later used for photo-offset reprinting. On Epstein’s Barukh she-amar, see above, n. 17, and on Walkin’s Sefer beit aharon al massekhet gittin, see his son’s introduction to the 1955 edition.

[38] See the address given for Epstein on the title page of his Sefer tosefet berakhah ha-kolel he‘arot ve-he’arot le-sefer “megillat sefer” al hamesh megillot ha-kodem (Krakow: [Michael Horowicz], 1930) (the same address appears on the title pages of the five parts of Sefer gishmei berakhah that appeared at the same press in the same year). It is unclear to me at what point he moved into the hotel referred to by Tarshish (see above, n. 34), though it seems, based on the aforementioned “List of Subscribers,” that as of 1939 a fellow named Dawid Giler was living at Epstein’s former address on Dominikańska Street.

[39] For several biographical sketches of R. Samuel David, the only child of R. Aaron to survive the war, see Samuel David Walkin, Sefer ramat shemu’el al ha-torah: sefer be-reshit (Jerusalem: Walkin Family, 1982), 11-27; the unpaginated introductions to idem, Sefer shevivei or: likkutim, ed. Samuel David Walkin [the grandson], 2nd ed. (Jerusalem: n.p., 2011); and idem, Sparks of Light: Jewels of Wisdom from the Chofetz Chaim ZT”L (New York: Kol Publishers, 2012), 83-86. For descriptions of R. Samuel David’s efforts on behalf of his fellow Pinskers, see Rabinowitsch, Pinsk, 547, and Tamir, Pinsk, 598-599. Unsurprisingly, given the interconnectedness of Lithuanian rabbinic dynasties, R. Samuel David became close with both the Hafets Hayyim and R. Soloveitchik; for photographs of him with the former, see the plates at the end of Sparks of Light, and with the latter, see Marc B. Shapiro, “Assorted Matters,” Seforim Blog (February 17, 2016) (accessed August 19, 2019).

[40] See Samuel David Walkin, Sefer kitvei abba mari: hiddushim u-be’urim al tanakh u-midrashav, ed. Moishe Joel Walkin (Kew Gardens: Yeshiva Beth Aron, 1989), 345; see also pp. 73, 132, 160, 266, 497, 512. For other instances of R. Samuel David quoting Epstein, often preceded by honorifics, see idem, Sefer ramat shemu’el al ha-torah, 108-109, and idem, Sefer kitvei abba mari: hiddushim u-be’urim al massekhtot ha-shas, u-mo‘adei ha-shanah[,] ve-nosaf aleihem derashot ve-he‘arot be-inyanei de-yoma, ed. Moishe Joel Walkin (Kew Gardens: Yeshiva Beth Aron, 1982), 33, 176, 193, 277, 314. For a reproduction of a letter written by Epstein (on his own letterhead) to R. Samuel David on the occasion of the latter’s appointment to the rabbinate of Lukatsh (present-day Lokachi, Ukraine) in 1935, see Tamir, Pinsk, 490. On the relationship between Epstein and R. Aaron, see also Seidman, “Ha-rav r. barukh epstein,” 144, 149. (Seidman, “Ha-rav r. aharon walkin,” 69, notes that Walkin opened his home and heart “to anyone suffering or in pain.” See also Zaretsky, “Rabbah ha-aharon shel pinsk,” 36. For a similar description of R. Samuel David, see Aaron B. Shurin, “Horav hagoen r. shmul wolkin, vitse prezident fun agudes horabonim, iz nifter gevorn,” Forverts [August 29, 1979]: 1, 8, at p. 1.) Another home Epstein visited was that of Yankev Epstein in Minsk; see Devora Gliksman, A Tale of Two Worlds (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, ltd, 2009), 113-114.

[41] Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 642, 648; see also Tamir, Pinsk, 319-320.

[42] Walkin himself refers to this, en passant, in the introduction to Sefer beit aharon al massekhet bava kamma, saying that he was jailed bi-shevil alilah, hattat ha-kahal hu (on account of libel; it is the sin of the community). R. Samuel David, in “Toledot maran ha-ga’on ha-mehabber,” explains that his father was one of those fighting to defend Jewish tradition against the edicts of the Bolsheviks and was therefore imprisoned for about half a year. Seidman, “Ha-rav r. aharon walkin,” 67, adds (perhaps by logical deduction) that the Yevsektsiya (Jewish section of the Communist Party) was responsible for informing on him to the authorities.

[43] For examples of Walkin’s wartime rabbinic activities, see Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 649; Tamir, Pinsk, 320; and Seidman, “Ha-rav r. aharon walkin,” 69, 71. For his commitment especially to Torah study and creativity in this period, see the excerpt from the last letter R. Samuel David received from him printed in “Toledot maran ha-ga’on ha-mehabber,” as well as the excerpt from a letter by Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin (1881–1966) reproduced in the introduction to Aaron Walkin, Sefer beit aharon al massekhet kiddushin, ed. Aaron ben Moishe Joel Walkin (Queens: Aaron Walkin, n.d.).

[44] See Tarshish, Rabbi, 127; see also p. 128 on Epstein’s avoidance of the Soviet authorities, even when it meant skipping meals. Zvi Gitelman, “Afterword: Pinsk in Wartime and from 1945 to the Present,” in Shohet, The Jews of Pinsk, 1881 to 1941, 652-659, at p. 653, notes that local leaders organized a committee to aid impoverished clergy, including Epstein, during this period.

[45] For harrowingly detailed accounts of the fate of Pinsk Jewry during the Nazi onslaught, see Nahum Boneh (Mular), “Ha-sho’ah ve-ha-meri,” in Tamir, Pinsk, 325-388 (a Yiddish translation by Leib Morgenthau appears on pp. 389-458 and an English translation by Ellen Stepak appears online here [accessed August 19, 2019]); Nadav, “Pinsk,” 294-298; Tikva Fatal-Knaani, “The Jews of Pinsk, 1939–1943, Through the Prism of New Documentation,” trans. Naftali Greenwood, Yad Vashem Studies 29 (2001): 149-182; Gitelman, “Afterword,” 652-654; and Katharina von Kellenbach, Nahum Boneh, and Ellen Stepak, “Pinsk,” in Martin Dean with Mel Hecker (eds.), The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, vol. II, pt. B (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1442-1444. For a map of the Pinsk ghetto, see Tamir, Pinsk, 334 (in Hebrew), and here (in English) (accessed August 19, 2019). For photographs of the memorials set up on the sites of mass murder, see here (accessed August 19, 2019).

[46] See, e.g., R. Samuel David’s introductions to Sefer she’elot u-teshuvot zekan aharon, vol. 2 (the one entitled “Hakdamat ben ha-mehabber maran ha-ga’on z[ekher] ts[addik] l[i-berakhah]”) and to Sefer beit aharon al massekhet gittin; see also the entries on R. Aaron maintained by Yad Vashem (1, 2, 3, 4) (accessed August 19, 2019). (I am aware that Hy”d is sometimes used even when a person was not literally killed by an enemy but rather died as a[n in]direct result of enemy persecution.) Strangely, Tamir, Pinsk, 636, does not list any members of the Walkin family among the martyrs of Pinsk.

[47] See Tamir, Pinsk, 500, and Zaretsky, “Rabbah ha-aharon shel pinsk,” 33, 37. For a relatively recent study of rabbinic leadership during the Holocaust, see Havi Dreifuss (Ben-Sasson), “‘Ka-tson asher ein lo ro‘eh’? rabbanim u-ma‘amadam ba-sho’ah,” in Asaf Yedidya, Nathan Cohen, and Esther Farbstein (eds.), Zikkaron ba-sefer: korot ha-sho’ah ba-mevoʼot la-sifrut ha-rabbanit (Jerusalem: Rubin Mass, 2008), 143-167.

[48] See Aaron B. Shurin, “Ha-rav aharon walkin: rabbah ha-aharon shel pinsk,” in Keshet gibborim: demuyyot ba-ofek ha-yehudi shel dor aharon, vol. 3 (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 2004), 92-97, at p. 92 (ca. Passover 1941), and Seidman, “Ha-rav r. aharon walkin,” 71 (summer 1942).

[49] See Gershuni, “Rabbi barukh epstein,” 887-890. It seems that Tarshish’s version of the events (Rabbi, 128), according to which Epstein died in a Jewish hospital shortly after the Germans’ invasion in July 1941, has gained some traction. See, e.g., N.T. Erline’s epilogue in Baruch ha-Levi Epstein, My Uncle The Netziv, trans. Moshe Dombey, ed. N.T. Erline (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1988), 223; Prof. Meir Bar-Ilan’s family tree (accessed August 19, 2019); and Pnina Meislish, “Epstein, barukh, ben yehi’el mikhl,” Rabbanim she-nispu ba-sho’ah (accessed August 19, 2019). By contrast, Gitelman, “Afterword,” 728 n. 7, claims that “Epstein died a natural death in Pinsk in 1940,” while Ber Schwartz, Sefer artsot ha-hayyim (Brooklyn: B. Schwartz, 1992), 23, writes that Epstein was killed by the Nazis in 1942. Here again, Samuel David Walkin, Sefer ramat shemu’el al ha-torah, 108, refers to Epstein with the acronym Hy”d, suggesting martyrdom; see also the entries on Epstein maintained by Yad Vashem (1, 2, 3) (accessed August 19, 2019).

[50] Paktor could not have directly witnessed Epstein passing away in the ghetto, as by the time of its establishment he had long been exiled to Siberia by the Soviets. Interestingly, Aaron B. Shurin, in an article published about six years after Paktor sent this letter, also writes that Epstein died in the ghetto (“Ha-rav barukh epstein: mehabber ‘torah temimah’,” in Keshet gibborim, vol. 3, pp. 38-44, at p. 44). He adds (without citing a source) that Epstein was buried in the Karlin Jewish cemetery next to the grave of Rabbi David Friedman of Karlin (1828–1915). Unfortunately, the Karlin cemetery is no longer extant, making it difficult to verify this claim; see here (accessed November 24, 2019).

[51] Ratnowska’s account (committed to writing twenty years after the Holocaust) is cited by Boneh, “Ha-sho’ah ve-ha-meri,” 333. (Pnina Meislish, it should be noted, accepts this timing with respect to Walkin’s passing only; see “Walkin, aharon, ben yosef tsevi,” Rabbanim she-nispu ba-sho’ah [accessed August 19, 2019].) Cf. Rabinowitsch, Pinsk, 399 n. 3, where he quotes slightly conflicting testimony from Ratnowska, according to which Epstein passed away “suddenly” a few weeks before the establishment of the Pinsk ghetto (which sounds more like springtime than winter). In addition, according to her, Epstein was buried in the cemetery in Pinsk, not in the Karlin cemetery as posited by Shurin (see previous note). For Ratnowska’s description of life in hiding during the war, see Boneh, “Ha-sho’ah ve-ha-meri,” 357.

Interestingly, Irina Yelenskaya places both rabbis’ deaths more specifically in January 1942 in her article on Pinsk for the Shtetl Routes project (accessed November 4, 2019), though I do not know on which of her sources she bases this date.

[52] See the description of the Pinsk Ghetto Database available here (accessed August 19, 2019). By contrast, Rachel Walkin (1876–1942?), R. Aaron’s wife, is listed in the Database as living at 35 Polnocna (in German: Nord) Street (the present-day approximate equivalent is Leningradskaya Street). Also listed are Mila Ratnowska and Eve Slutzky (who is presumably to be identified with the daughter of alderman Jacob-Alter bearing the same name).

[53] See the May 2, 2011 funeral announcement published in the Chicago Tribune and currently available here (accessed August 19, 2019).