Eli Genauer: Breishit 9:18 – Noach’s Family or Noach’s Drunkenness?

Breishit 9:18 – Noach’s Family or Noach’s Drunkenness?

Eli Genauer

וַיִּֽהְי֣וּ בְנֵי־נֹ֗חַ הַיֹּֽצְאִים֙ מִן־הַתֵּבָ֔ה שֵׁ֖ם וְחָ֣ם וָיָ֑פֶת וְחָ֕ם ה֖וּא אֲבִ֥י כְנָֽעַן׃

“The sons of Noach who came out of the ark were Shem, Cham, and Yefet; and Cham was the father of Canaan.”

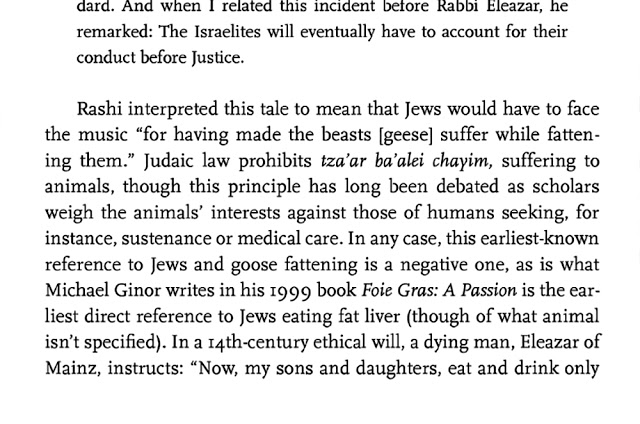

Rashi:

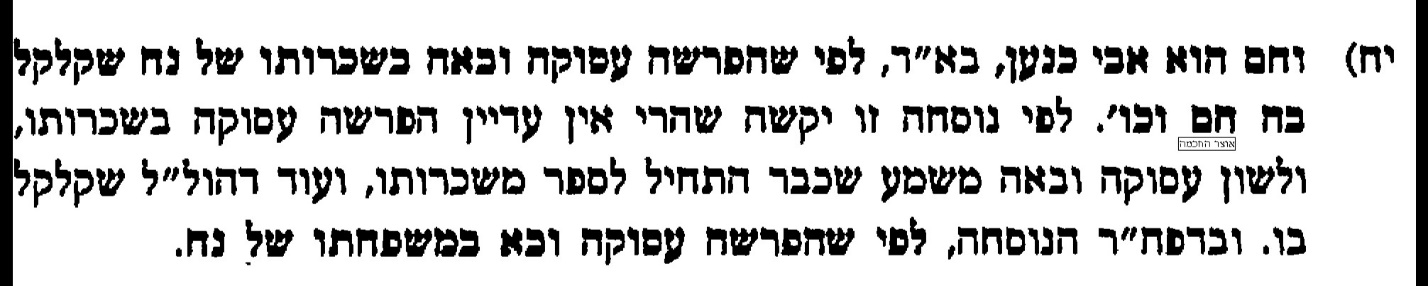

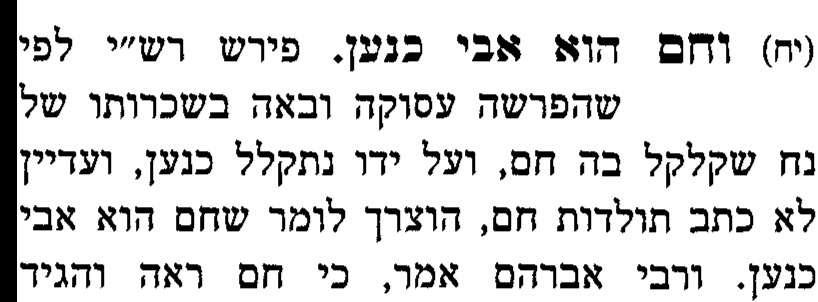

וחם הוא אבי כנען. לָמָּה הֻצְרַךְ לוֹמַר כָּאן? לְפִי שֶׁהַפָּרָשָׁה עֲסוּקָה וּבָאָה בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ שֶׁל נֹחַ שֶׁקִּלְקֵל בָּה חָם וְעַל יָדוֹ נִתְקַלֵּל כְּנַעַן, וַעֲדַיִן לֹא כָתַב תּוֹלְדוֹת חָם, וְלֹא יָדַעְנוּ שֶׁכְּנַעַן בְּנוֹ – לְפִיכָךְ הֻצְרַךְ לוֹמַר כָּאן וְחָם הוּא אֲבִי כְנָעַן:

AND CHAM IS THE FATHER OF CANAAN – Why is it necessary to mention this here? Because this section goes on to deal with the account of Noah’s drunkenness when Cham sinned, and through him, Canaan was cursed. Now, as the generations of Cham have not yet been mentioned, we therefore would not know that Canaan was his son. Therefore, it was necessary to state here that “Cham is the father of Canaan”.

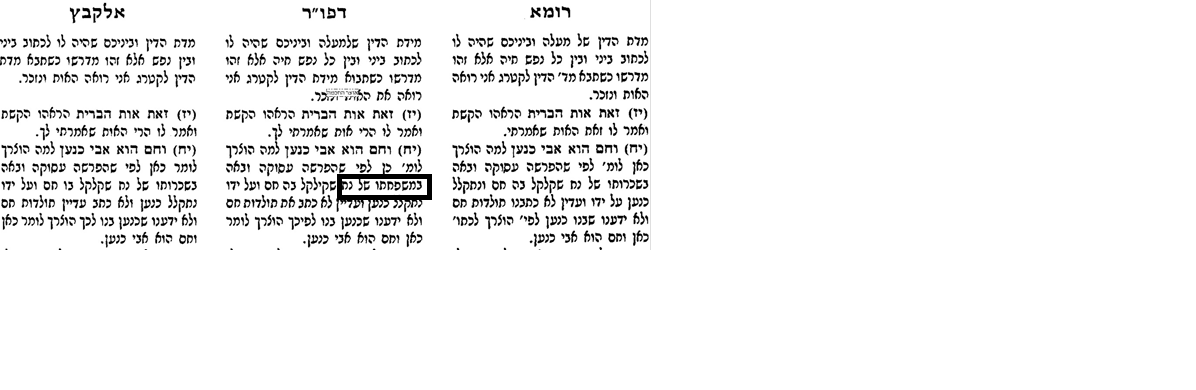

This is how it appears in the Artscroll Elucidated Rashi[1]:

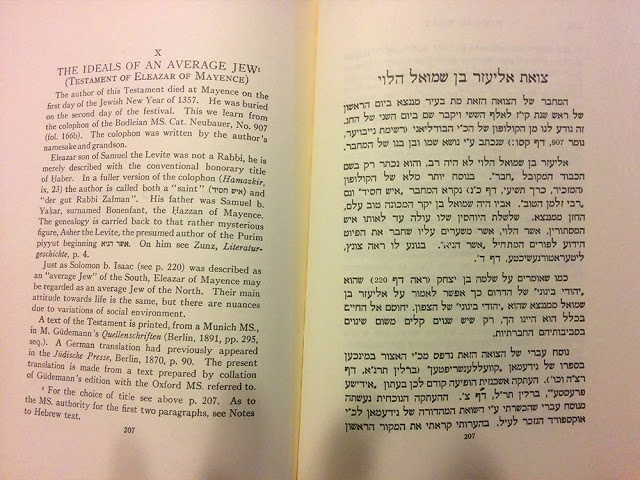

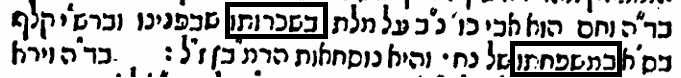

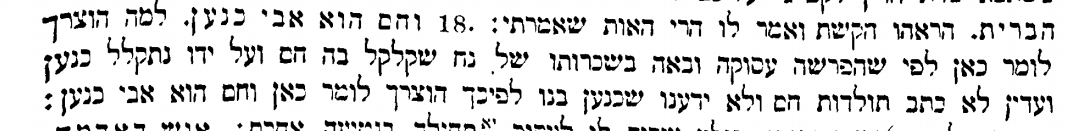

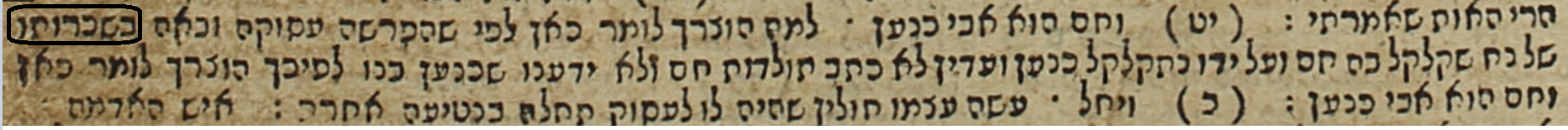

Yet the author of the Sefer Yosef Da’at (Prague 1609) writes that he had a Rashi manuscript and other Sefarim which substituted the word “במשפחתו “for the word” בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ”. He also writes that it was the Nusach of Ramban ( when quoting this Rashi).

בדבור המתחיל וחם הוא אבי כו׳, נכתב בצדו על מלת ״בשכרותו״ שבפנינו, וברש״י קלף בס״א (בספרים אחרים) במשפחתו של נח. והיא נוסחאות הרמב״ן ז״ל.

The text of Rashi would then read:

וחם הוא אבי כנען. לָמָּה הֻצְרַךְ לוֹמַר כָּאן? לְפִי שֶׁהַפָּרָשָׁה עֲסוּקָה וּבָאָה במשפחתו שֶׁל נֹחַ שֶׁקִּלְקֵל בָּה חָם וְעַל יָדוֹ נִתְקַלֵּל כְּנַעַן…..

Why is it necessary to mention this here? Because this section goes on to deal with the account of Noah’s family when Cham sinned, and through him, Canaan was cursed…

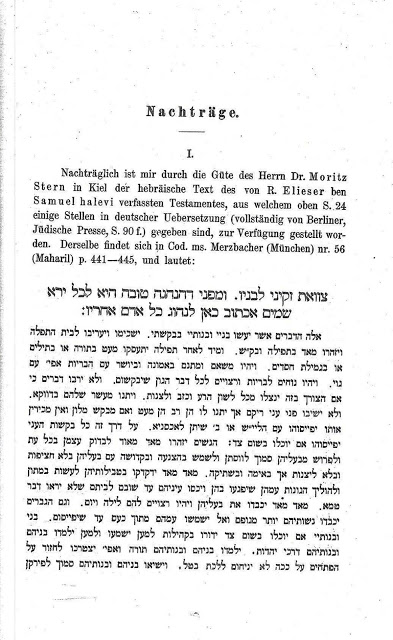

As mentioned by Yosef Da’at, one of the Eidei Nusach for having the word במשפחתו is Ramban, who quotes Rashi’s comment. The website Al Hatorah notes, that this Nusach appears in the following Ramban manuscripts: Parma 3255, Munich 138, Fulda 2, Paris 222, and Paris 223. It also appears that way in the first printed edition of Ramban, that of Rome (printed before 1490).

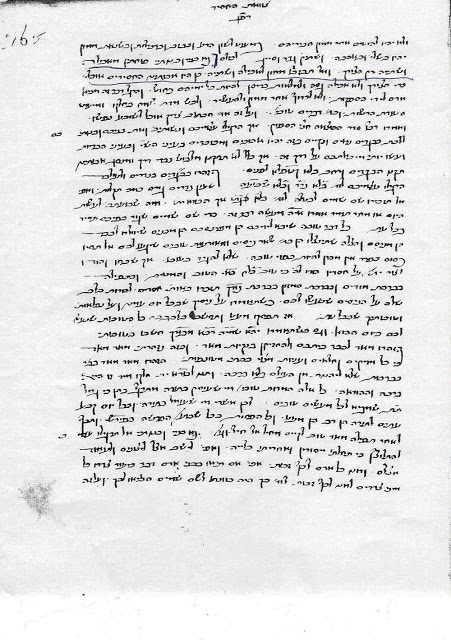

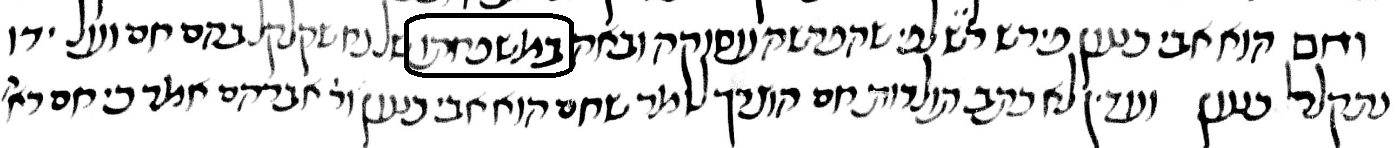

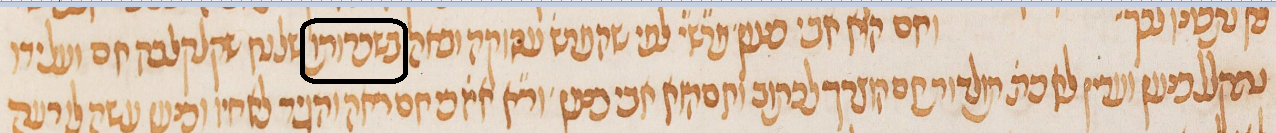

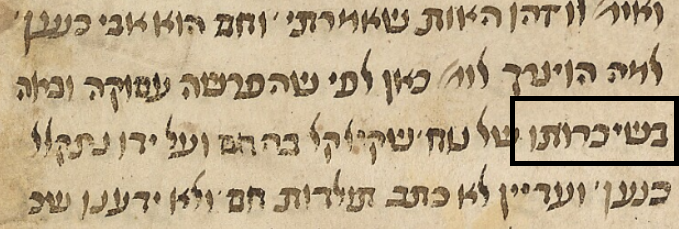

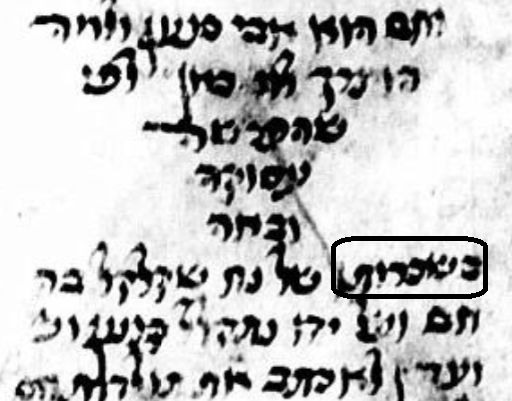

This is the Ramban manuscript known as Munich 138 where Ramban quotes Rashi:

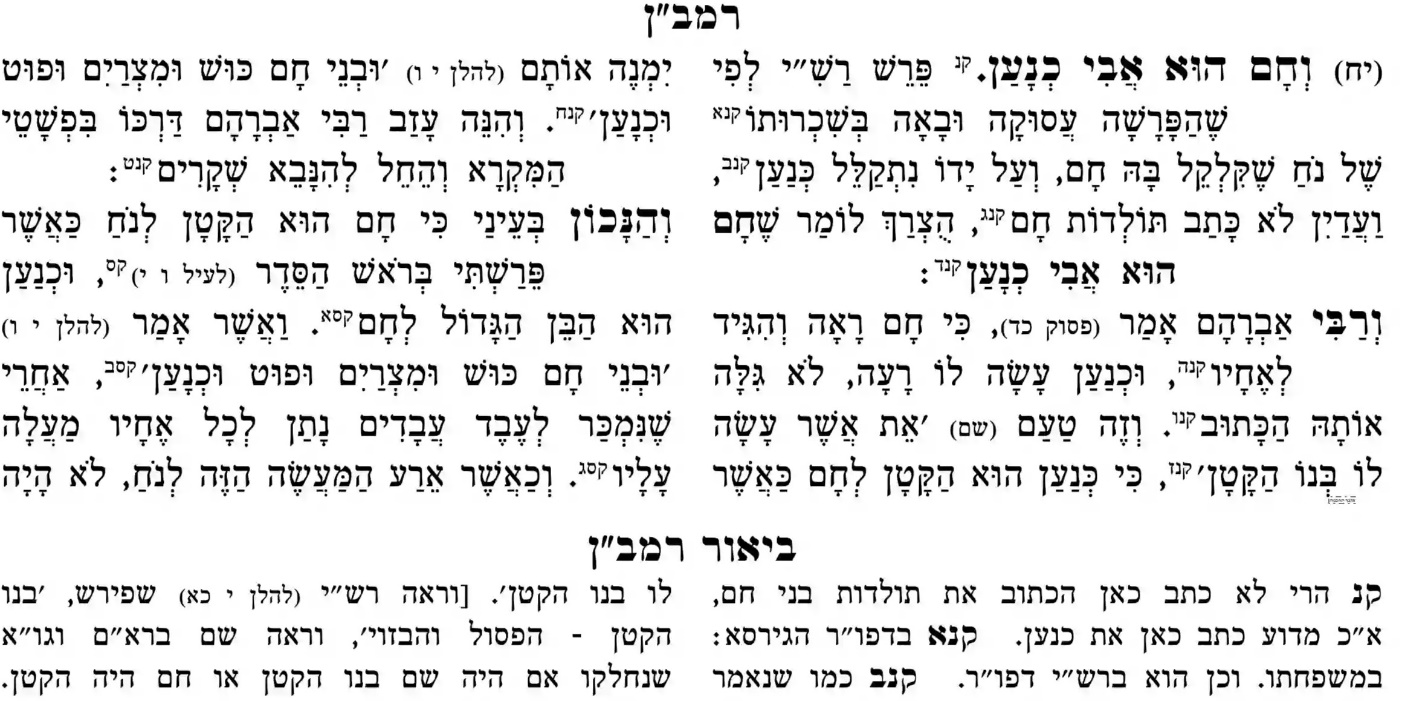

Here is the text of Ramban in the Rome edition where he writes(פ׳(רוש) ר״ש (למה:

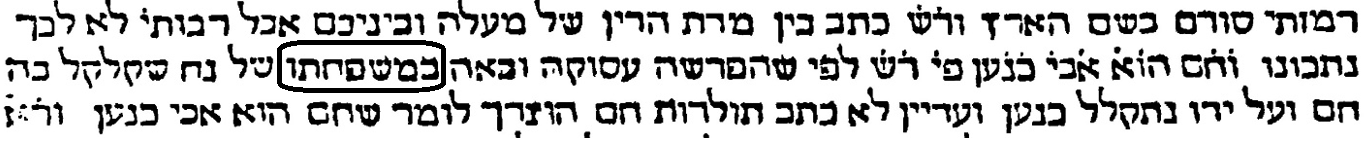

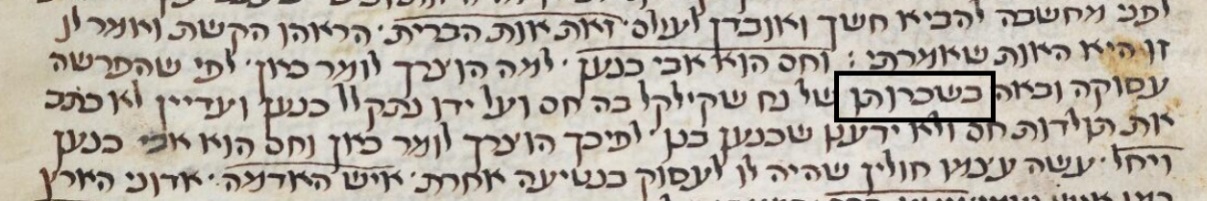

Al Hatorah also notes that the word במשפחתו, appears in the text of a Rashi manuscript, Parma 3115, (which it seems was close to the text with which the Ramban worked) before it was “corrected”.

וכן בכ”י פרמא 3115 של פירוש רש”י (שהוא כנראה קרוב לנוסח שעמד בפני רמב”ן) לפני שתוקן בין השיטין

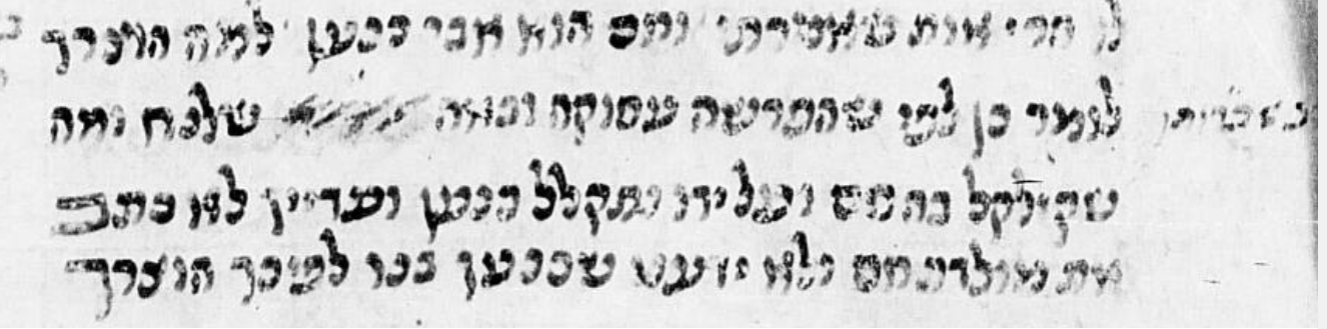

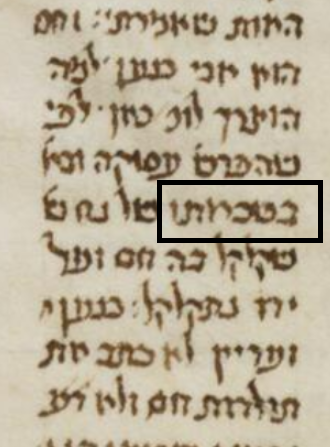

Ktav Yad Parma 3115, for Rashi:

Al Hatorah then notes that most Rashi manuscripts have בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ

בכ”י רומא 44, פרמא 2978, דפוס ליסבון: “בשכרותו”, וכן ברוב כ”י של רש”י.

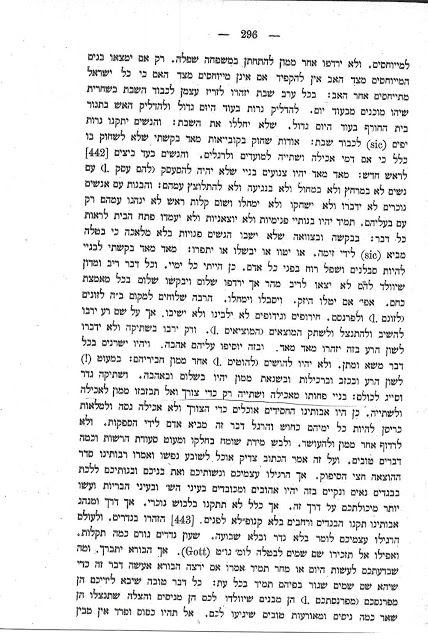

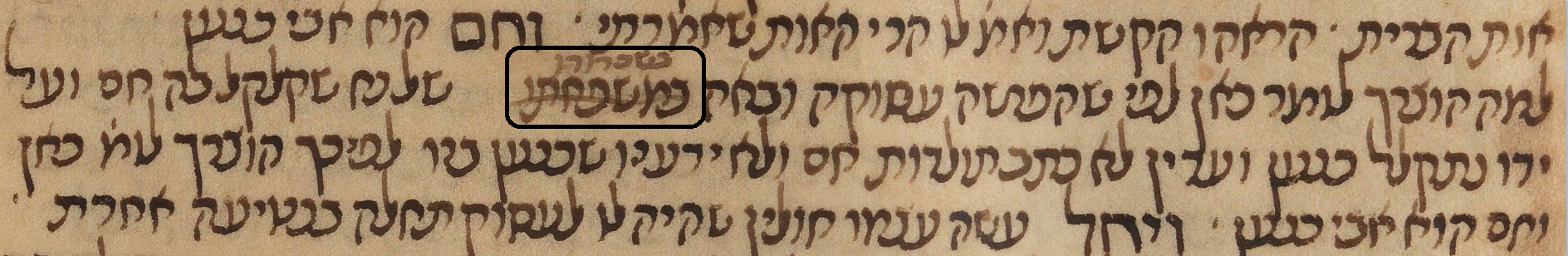

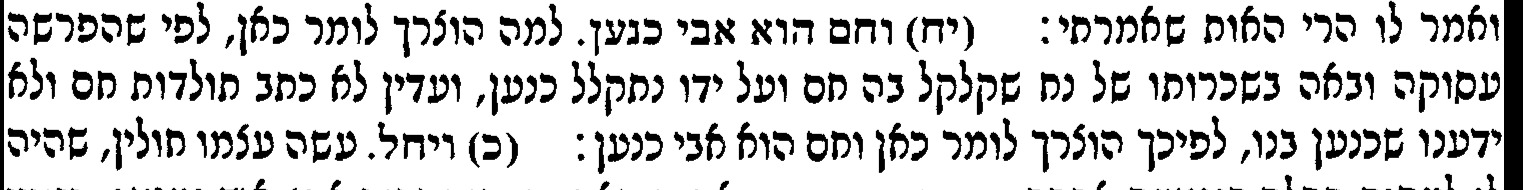

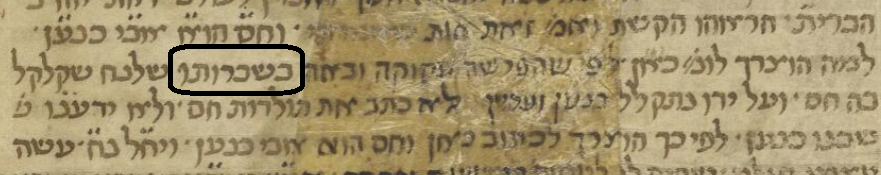

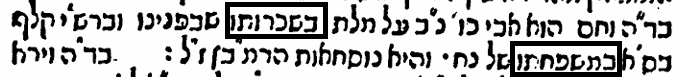

Parma 2978 is the Ramban on Noach which has “בשכרותו”:

For Rashi on this Pasuk ,Al HaTorah records that most Rashi manuscripts have בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ, but Regio di Calabria, as quoted by Ramban and the Rashi manuscript Parma 3115, have it as במשפחתו.

וחם הוא אבי כנען – למה הוצרך לומר כאן. לפי שהפרשה עסוקה בשכרותו של נח שקלקל בה חם, ועל ידו נתקלל כנען, ועדיין לא כתב תולדות חם, ולא ידענו שכנען בנו. לפיכך הוצרך לומר כאן: וחם הוא אבי כנען.

ב. כן בכ״י אוקספורד 165, מינכן 5, אוקספורד 34, לונדון 26917, ברלין 1221, דפוס רומא.

דפוס ריגייו: ״במשפחתו״, וכן מופיע בפירוש רמב״ן כאן ברוב עדי הנוסח, בכ״י פרמא 3115

. אפשר שכך היה הנוסח גם בכ״י המבורג 13.

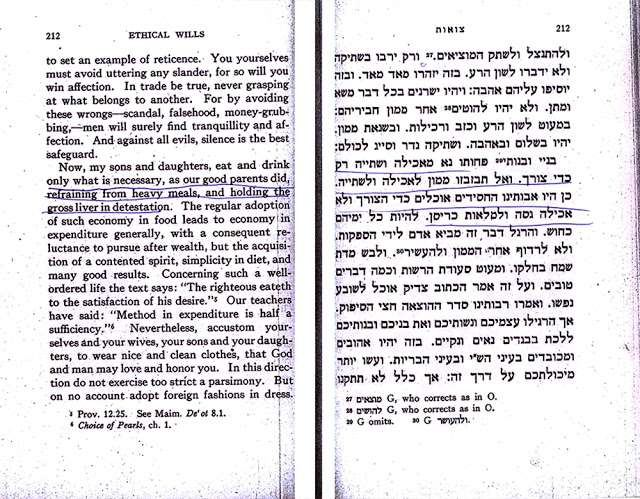

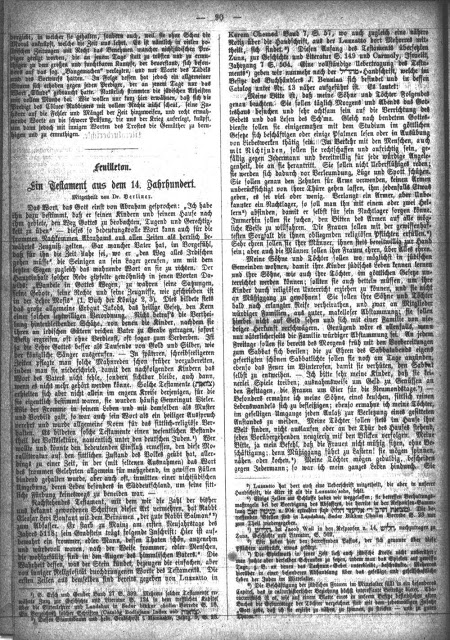

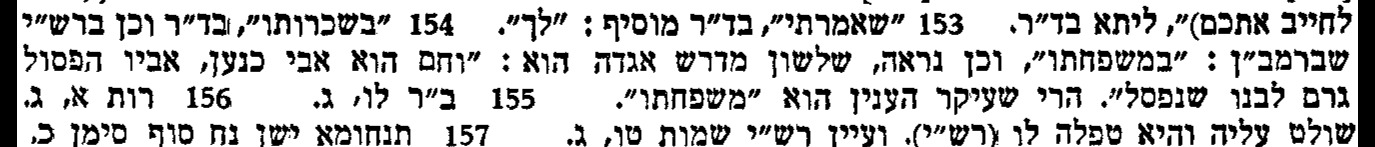

In Zechor L’Avraham (Berlin 1867 and Frankfurt am Main 1905), there is no indication of alternative Nusach. Avraham Berliner does not mention the alternative Nusach of Yosef Daat, the Dfus Rishon or the Girsa of Ramban:

In Yosef Hallel (Brooklyn 1987), Rabbi Brachfeld notes that the Dfus Rishon of Regio Callabrio (1475) has the word במשפּחתו. He does not note that it is the Lashon of the Ramban but seems to think that במשפחתו is a better reading because of his questions on the use of בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ:

In Rashi HaShalem Mechon Ariel ( Jerusalem 1987), there is no indication of another Girsa but in the back of the Sefer, it does have it as part of Defusim Rishonim:

Defusim Rishonim:

Guadalajara (1476) Reggio di Calabrio (1475) Rome (1470)

It is interesting to note that the Alkbetz edition is what is known as the Mahadura Sefardit ( according to Professor Yeshayahu Sonne and Dr Yitzchak Penkower), and yet it has בשכרותו. The same goes with Hijar(1490), which generally copies Alkabetz.

Oz Vehadar Rashi HaMevuar 2008, has במשפחתו in the back in Chilufai Girsaot, noting that it is the Girsa of Ramban and the Dfus Rishon:

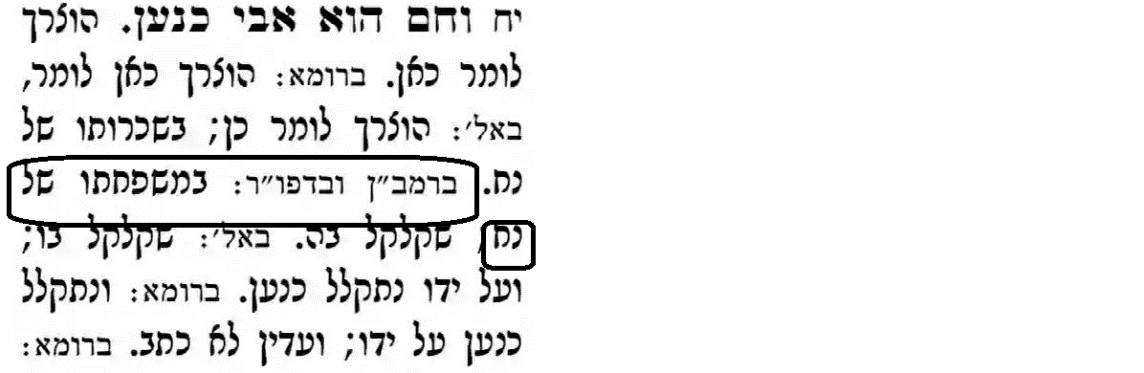

Rabbi Isaac Chavel in his edition of Rashi ( Mosad HaRav Kook – 2007 edition) notes that Defus Rishon of Rashi (Regio di Calabria) has ,במשפחתו and this Lashon also appears in the text of Ramban as he quotes Rashi. He also says about the use of the word “במשפחתו” that is more correct (“וכן נראה”) based on the Lashon of the Midrash Agadah which places the emphasis on familial relationships of Noach:

What do the manuscripts indicate:

Oxford CCC 165 (Neubauer 2440) – 12th century

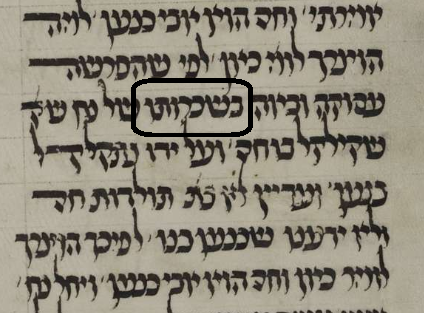

Hamburg 13 (1265), has the word in question rubbed out and changed to בְּשִׁכְרוּתו on the side. It might have originally said במשפחתו:

Oxford-Bodley Opp. 34 (Neubauer 186):

London 26917 (Neubauer 168) (1272):

Berlin 1221:

Vatican Urbinati 1 (1294):

Nuernberg 5 (1297):

How did the text of Rashi in printed editions evolve over time?

The Dfus Rishon of Regio di Calabrio recorded it as במשפחתו. As mentioned, Yosef Da’at noted במשפחתו as a variant reading in a Rashi Klaf and in ,ספרים אחרים and bolstered it with it being the Nusach of Ramban:

בדבור המתחיל וחם הוא אבי כו׳, נכתב בצדו על מלת ״בשכרותו״ שבפנינו, וברש״י קלף בס״א (בספרים אחרים) במשפחתו של נח. והיא נוסחאות הרמב״ן ז״ל.

Hanau 1611-1614, regularly included the Girsaot of Yosef Da’at so we would have expected it to have had בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ and then in parentheses have Sefarim Achairim as במשפחתו. But is doesn’t, and that sealed the fate of that Nusach in terms of it becoming a mainstream Girsa of Sefarim Achairim:

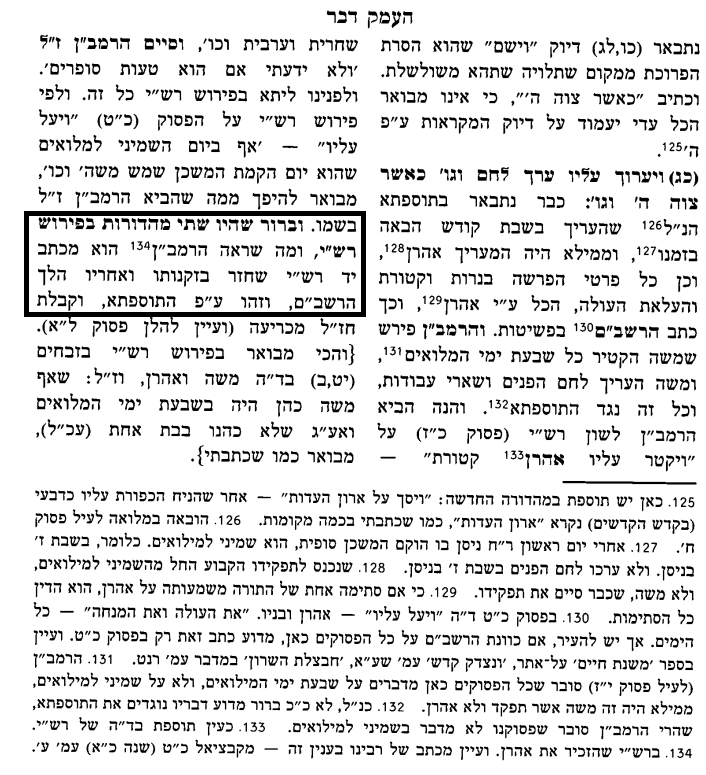

The Netziv in Shemot 40:23 cites a comment of the Ramban in which he quotes Rashi and says that our text of Rashi is different. He proposes that there were two Mahdurot of Rashi, of which Ramban had the first Mahadura and we have the second one. In that second Mahadura, Rashi reversed himself from what he said in the first Mahadura. It is possible that this occurred here- in the first Mahadura, Rashi wrote במשפחתו and that is the Mahadura which Ramban had. Later on, Rashi changed it to בְּשִׁכְרוּתו and that has become the standard Girsa:

The Netziv in Shemot 40:23 cites a comment of the Ramban in which he quotes Rashi and says that our text of Rashi is different. He proposes that there were two Mahdurot of Rashi, of which Ramban had the first Mahadura and we have the second one. In that second Mahadura, Rashi reversed himself from what he said in the first Mahadura. It is possible that this occurred here- in the first Mahadura, Rashi wrote במשפחתו and that is the Mahadura which Ramban had. Later on, Rashi changed it to בְּשִׁכְרוּתו and that has become the standard Girsa:

Conclusion:

There is a lot of ammunition for the Girsa being במשפחתו:

- It is in Dfus Rishon, (indicating either inclusion in a manuscript or taken from Ramban)

- It is the Lashon of the Ramban, (this is the main argument)

- It has logic behind it (Rabbi Chavel’s and Yosef Hallel’s comments)

- It is attested to by Yosef Da’at as being in a manuscript

- Parma 3115 originally had “במשפחתו”

- Hamburg 13 was altered and could have said במשפחתו

But it did not survive as an alternative Girsa of ספרים אחרים today mainly because the influential edition of Hanau (1611-1614) did not include it.

Sidenote:

Many editions of the Ramban today still attribute the word בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ to Rashi even though it is clear that the original Ramban had במשפחתו. This was most likely done to make it conform with the accepted Nusach of Rashi.

Here is Oz Vehadar Jerusalem on Ramban 2015 which has בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ but says it is במשפחתו in Defus Rishon:

Here is Peirush HaRamban with Peirush Menachem Tziyon printed in 2019 which also has בְּשִׁכְרוּתוֹ:

- There is no comment on this Rashi in the Siftei Yeshainim section ↑