A Young Man Holding a Torah Scroll and a Young Woman Holding a Book: The Life and Afterlife of Two Illustrations

A Young Man Holding a Torah Scroll and a Young Woman Holding a Book:

The Life and Afterlife of Two Illustrations

By Rachel Manekin

Rachel Manekin is Professor Emerita of Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland. Her area of specialization is the social, political, and cultural history of Galician Jewry. She is the author of The Jews of Galicia and the Austrian Constitution: The Beginning of Modern Jewish Politics (Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 2015, Hebrew), and most recently, The Rebellion of the Daughters: Jewish Women Runaways in Habsburg Galicia (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2024; Hebrew). Her previous essay at The Seforim Blog was in Rachel Manekin and Charles (Bezalel) Manekin, “The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s Statement on Teaching Torah to Girls in Likutei Halakhot: Literary and Historical Context,” The Seforim Blog (27 May 2020), available here.

The 1922 illustration below of a young man holding a Torah scroll has gained a new life within the context of recent Bais Yaakov scholarship and a partial image of it appears on the main page of the Bais Yaakov Project website.[1]

This article calls into question this use of the illustration and shows that it has no connection to the Bais Yaakov movement, or Orthodox women, at least in interwar Poland. The article first traces the origin of the illustration and the context in which it was used after its first publication, and then examines the campaign proposed in 1933 to mobilize Bais Yaakov students in Poland to support financially the writing of a Torah scroll. Finally, the article presents an interwar illustration of a young woman holding a book with a tall Hanukkah menorah in the background. The latter was used as a symbol of Bais Yaakov in Viennese publications in the German language, but never appeared in Polish Yiddish publications of the Bais Yaakov movement. The article suggests a possible reason for that.

The illustration of the young man holding the Torah scroll appeared first on a postcard, one in a set of ten “art postcards” drawn by Uriel Birnbaum, the son of the general secretary of Agudath Yisrael, Nathan Birnbaum. The postcards were produced by the Viennese Tseirei Agudath Yisrael organization (Agudas Jisroel Jugendgruppe) and sold for fundraising purposes. The price of each set was 500 krone. Indeed, in May 1922 the Austrian Orthodox weekly Jüdische Presse published advertisements for this set.[2]

In 1924 the Viennese Menorah Journal published two of the postcards in a long article dedicated to Uriel Birnbaum.[3]

Each postcard had a black and white illustration of a Biblical theme with a Biblical verse under it. One can see the original envelope and some of the postcards (including the youth with the Torah scroll) in an advertisement published on February 28, 2023, on the website of Kedem Auction House:[4]

The postcard with the illustration of the youth holding a Torah scroll as if rescuing it from the whirlwind in the background (perhaps symbolizing the First World War) appears with the verse from Jeremiah 1:7, “Do not say I am a youth, for to whomsoever I shall send thee thou shalt go and whatsoever I shall command you thee thou shalt speak” (אַל תֹּאמַר נַעַר אָנֹכִי כִּי עַל כָּל אֲשֶׁר אֶשְׁלָחֲךָ תֵּלֵךְ וְאֵת כָּל אֲשֶׁר אֲצַוְּךָ תְּדַבֵּר). The import in this context is that one should not excuse himself from obeying God’s commandment, interpreted here as spreading Torah study, by claiming to be a youth.

The youth is wearing a long kapota reaching his feet, as did many at the time, and his head, especially the back of it, is all colored in black and so one cannot see the skullcap. Still, it is obvious that this is a young male, not only because of the Biblical verse under it, but also because it is absolutely inconceivable that a female carrying a Torah scroll would appear in an Agudath Yisrael sponsored postcard in the 1920s (or, for that matter, today).

After its original publication as a postcard, the illustration was used always in the context of male Torah study. To the best of my knowledge, it first was featured in the 1925 booklet of Keren ha-Torah (חוברת של קרן התורה) which included several other of Uriel Birnbaum’s postcard illustrations.[5] The illustration appears at the top of a rabbinical appeal (קול קורא) that was published in the wake of the First Assembly of Agudath Yisrael (1923) to support Keren ha-Torah. It stretches over several pages and is signed by major Agudah rabbinical figures of the time, with the Ḥafetz Ḥayim and the leaders of the Czortków and Ger Hasidic dynasties appearing first. The illustration was edited to include only the image and not the Biblical verse. Keren ha-Torah was established during the First Assembly in the purpose of supporting yeshivas, many of which collapsed during the First World War.

It should be noted that contrary to claims in recent scholarship on Bais Yaakov, there is no evidence that the First Assembly of Agudath Yisrael in 1923 mentioned the Bais Yaakov schools, and the published reports of the assembly included nothing about the support of religious education for girls.[6] During the 1924 meeting of the Central Council of Agudath Yisrael in Kraków, several delegates called for actual steps to be taken by Keren ha-Torah to support Bais Yaakov schools. Indeed, after major rabbinical figures supported this idea, the participants at a special meeting in the winter of 1925 drew up a plan to financially support the establishment of a teachers’ seminary and improve professionally the Bais Yaakov school system, all under the leadership of R. Dr. Shmuel Leo Deutschländer, the director of Keren ha-Torah. It was only during the Second Assembly of Agudath Yisrael (1929) that Bais Yaakov was mentioned.[7]

Birnbaum’s illustration of the youth with a Torah scroll later appeared in Luach Blätter der Agudas-Jisroel Jugendgruppe-Wien, the periodical of the Viennese Tseirei Agudath Yisrael, for the year 1931, this time with the Biblical verse.

A 1937 publication of Keren ha-Torah also included this illustration, albeit without the Biblical verse. It appeared on the title page of the first chapter which was dedicated to the discussions on male Torah education in the Second Assembly of Agudath Yisrael (1929).[8]

The same 1937 publication included a chapter with supplements the largest of which discussed in detail the Bais Yaakov schools. The heading of this chapter had an illustration of a young woman holding a book to which we will return below.

First, however, I wish to discuss the aforementioned campaign for writing a Torah scroll which was introduced in a Bais Yaakov Journal article in the Hebrew month of Iyar, 1933, titled: “The ‘Yehudis’ Camp’s Own Torah Scroll Will Be Written Through the Students of the Bais Yaakov Schools in Poland.”[9]

The article describes the plan for purchasing letters by Bais Yaakov students for a Torah scroll to be written for the Yehudis summer camp.[10] Camp Yehudis, according to articles published in the 1933 journal, was the first permanent summer camp built for Orthodox children, boys and girls. The journal includes two photographs of children in the camp, one of boys and another of girls.

Clearly, this summer camp was not intended exclusively for Bais Yaakov girls as can be seen also in a photograph kept in the YIVO archives of boys in the camp playing chess.[11]

The plan to have Bais Yaakov students raise money for writing a Torah scroll was proposed by Yoel Unger, a Warsaw Agudah activist and the director of one of the Bais Yaakov schools in the city. Unger was in charge of the Yehudis association,[12] and it was he who came up with the initiative to build a summer camp. Indeed, the camp was built in 1931 in the village of Długosiodło, 73 km north-east of Warsaw.[13] In the years prior to that, the Yehudis association rented camp facilities for the summer, first in 1929 in Marązy and then in 1930 in Otwock. The aim of the summer camp was to provide children, many of whom came from impoverished families, with an opportunity to enjoy fresh air and water as well as physical exercises in a country setting. In doing that, it followed what was already a norm for non-Orthodox Jewish organizations in interwar Poland. In later years the summer camp added a sanatorium for children who were at risk of tuberculosis.[14]

The number of girls in the new camp exceeded the number of boys,[15] perhaps because boys went to cheder also in the summer months.

Why was obtaining a Torah scroll necessary for a summer camp for children that apparently did not even have its own synagogue?[16] The girl campers, according to Esther Goldshtof, prayed on Friday night and on Sabbath morning in the forest surrounding the camp while sitting on benches.[17] It is not clear from the articles in the Bais Yaakov Journal whether the boys – all younger than 13 – did the same or whether they prayed in the town’s synagogue. Of course, one could place a Torah scroll in one of the rooms and have the boys pray and hear the Torah reading there. But it is more likely that Unger intended to use the money raised also for the camp itself, which struggled with a deficit because of the high expenses of running it.[18] Only a small number of children paid the full tuition, while the rest received a discount or went there for free.[19] The camp did receive financial support from the Viennese Keren ha-Torah, the Warsaw Jewish community, German Jewish organizations, the American Joint, as well as some large donations from rich Jews. Small donations from individuals also helped as those apparently accumulated to large sums.[20] In addition, Bais Yaakov raised money from their students to support the camp, mostly with the help of teachers in the three Bais Yaakov schools in Warsaw and some from Bais Yaakov schools in Rzeszów, Sosnowiec, Częstochowa, Wolbrom, Szydłowiec, Bychawa, Płock, Bełchatów, and Pińczów. Those were small sums amounting to 10-60 zlotys.[21]

This was the context of Unger’s somewhat ambitious plan to recruit Bais Yaakov teachers to raise money for writing a Torah scroll, as explained in the 1933 Bais Yaakov Journal article.

Reaching Bais Yaakov teachers would be relatively easy since one could use advertisements in the Bais Yaakov journal to which all teachers were required to subscribe, or contact Bais Yaakov schools directly, the addresses of which were kept in the central Bais Yaakov office in Kraków. There was no parallel journal or a central office with the addresses of all cheders and Talmud Torahs. The 1933 Bais Yaakov Journal article explained that “the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll, which only individuals are able to fulfill, will be done now through the Bais Yaakov students with their own efforts.” Unger refers here to the positive commandment obligating every individual Jew to write a Torah scroll for himself or hire a scribe to do it for him. Since this is an expensive endeavor, it is allowed to pay for it in partnership with others.[22] At the same time, the article added, the money collected would also support Bais Yaakov students who cannot afford the camp tuition. Clearly, Unger himself explained that the money raised was meant not only for writing the Torah scroll.

Unger proposed that the Yehudis association would send to all Bais Yaakov schools signature forms with a picture of a Torah scroll. The price of purchasing a letter to be written in the scroll would be 25 groshen (pennies), and the names of all those who purchased a letter would be inscribed in a special book. However, each Bais Yaakov student would need to purchase a letter and sell at least one additional letter. A student who sold at least ten letters would receive gratis an additional letter in her name. The teachers responsible for selling 200 letters would have their names etched forever on a special board, and in addition they would be able to have a whole word in the Torah scroll on their name with a great discount.

But Unger proposed even more than this. The day that the writing would commence would be declared a holiday (יום טוב) in all Bais Yaakov schools. On this day the teachers would deliver lectures about the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll,[23] and organize celebrations and special programs. When the writing of the Torah scroll would be completed – scheduled for 15th of the Hebrew month of Av – a three-day Siyum celebration would take place in Długosiodło with the participation of all Bais Yaakov teachers, students’ delegations, the central administrations of Yehudis and the Bais Yaakov schools in Warsaw, Kraków, and Łódź. Unger also proposed that at the time of the Siyum celebration a special conference for Bais Yaakov teachers and operatives (‘askanim) would take place in Długosiodło to discuss all the problems of the movement. It is to be expected, he wrote, that the Bais Yaakov teachers would understand the important significance of this campaign, which would for sure be a wellspring of joy and enthusiasm for Bais Yaakov children and would unite them into one family that owned its own Torah scroll. It would also help the camp financially and enable it to develop so it could accept more children in need. “That is why our teachers,” Unger envisioned, “will work for the campaign with energy and dedication.” Unger added that in the following days the Yehudis association would send out the first circular with instructions regarding this important campaign.

But this ambitious and elaborate plan never came to pass, as is clear from two articles published in the Agudah newspaper, Dos Yudishe Togblat, a month after the death of Sarah Schenirer, which provided an opportunity to relaunch the project.[24] The first article, written by Abraham Mordechai Rogovy, who was involved in many aspects of Bais Yaakov, reports that the Education Center (מרכז החינוך) of Agudath Yisrael has now proclaimed for Benos and Bais Yaakov girls a campaign of writing a Torah scroll for the summer camp to memorialize Sarah Schenirer. The initiator was Yoel Unger, who had already made a name for himself as an expert fundraiser. Rogovy does not mention purchasing letters or fulfilling the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll (the word “mitzvah” does not appear at all), but rather that there is not a more beautiful monument for Schenirer “than a Torah scroll written in partnership (בשותפות) with tens of thousands of Jewish religious girls.” The life-ideal of Schenirer, he continues, was always to connect Jewish girls to the Torah, so that their entire being and every thread of their gentle souls would feel the connection of Israel and the Torah (ישראל ואורייתא). He also writes that “there is no better manifestation of the wish to remain loyal to the teachings of Sarah Schenirer a”h than to join a common Torah campaign that should include all the Benos and the Bais Yaakov students,” or that the “Torah campaign will be transformed into a great manifestation of the Benos and Bais Yaakov idea.” Interestingly, there is no mention of the role of Bais Yaakov teachers; rather Rogovy calls on the (male) ‘askanim of Bais Yaakov and the (female) activists of Benos “to throw themselves with energy in the collection.” According to Rogovy, the writing of the Torah scroll is expected to start on 33 of the ‘Omer )May 21) and be completed on the 15th of Av (August 14). Like Unger’s original plan, Rogovy also talks about a “grandiose” Siyum celebration after which everyone will travel to Schenirer’s tombstone in Kraków, where they will announce that a Torah scroll in her memory was completed.

The second article presents an undated letter that Schenirer wrote to Bais Yaakov girls, presumably following Unger’s 1933 article in the Bais Yaakov Journal, encouraging them to buy letters for the Torah scroll. The article explains that although the project was not carried out then “for various reasons” it has now been renewed by the initiators. “‘Keren ha-Torah’ with Agudath Yisrael are about to write a Torah scroll named after Sarah Schenirer, may she rest in peace.”

Schenirer’s letter, which has hitherto been unnoticed, reveals an important point not indicated in any of the articles cited above, namely, the audience for the Torah scroll. Ascribing to the Warsaw ‘askanim the establishment of the Yehudis summer camp, Schenirer explains that they thought that the boys who benefit from the camp should have a Torah scroll of their own so they would not have to use a Torah scroll that was already donated to some “bais midrash” [in the area]. By buying letters, Schenirer writes, the girls would not only be “fulfilling the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll,” but also be participating in writing a Torah in which it is written עֵץ חַיִּים הִיא לַמַּחֲזִיקִים בָּהּ וְתֹמְכֶיהָ מְאֻשָּׁר. In short, Schenirer saw the goal of the project to provide a sefer Torah for the boys in the camp, and to involve girls in the mitzvah of its production by buying letters.

While the article does not explain why the first campaign never got off the ground, one may speculate that the sum collected just was not enough for the project. (Schenirer writes in the beginning of her letter that she knows that more than one will complain about being asked again for money, especially at such difficult time.) Perhaps the initial project was frowned upon by some parents or rabbis. After all, the idea that Bais Yaakov girls would be fulfilling the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll made little sense since according to most religious legal opinions, women are exempt from this mitzvah, not to mention that most girls were minors.[25] Indeed, Unger’s 1933 article does not mention rabbinical support for his proposal. The second initiative avoided, as we have seen, mentioning buying letters or referring to it as the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll, and instead talked simply about a “collection.”

Apparently, the second initiative did not materialize either; had a Torah scroll in memory of Schenirer been written, it would have surely been reported in the Bais Yaakov journal or in Dos Yudishe Togblat.

We now come to the illustration mentioned above of the young woman holding a large book with a tall Hanukkah menorah in the background that is found in the 1937 Keren ha-Torah publication.[26]

In fact, this illustration had appeared already in 1935 on the title page of a Keren ha-Torah booklet containing a report written by Deutschländer on the activities of the central office of the Bais Yaakov schools.[27]

Although the publications where this illustration appeared do not have the name of the artist, the style of the illustration suggests that it might also have been Uriel Birnbaum.

The unusually large book that the young woman is holding and the tall menorah in the background are not explained. We may speculate that the young woman in the illustration portrays a Bais Yaakov teacher as a modern “Judith”, a heroine who saves the Jewish people. Whereas the classical Judith held in her arms the head of the decapitated enemy general, Holofernes, this Judith holds a book (ספר, בית ספר). European artists have painted the scene of Judith carrying the head of Holophernes for centuries.

Connecting the illustration to Judith would explain the Hanukkah menorah in the background, for in the Jewish medieval tradition, Judith was associated with Hanukkah.[28] Moreover, Sarah Schenirer, who established the first Bais Yaakov school, records in her 1933 published memoir that she was inspired by the sermon delivered by R. Moshe David Flesch in Vienna on the Sabbath of Hanukkah which described the greatness of Judith and called contemporary Jewish women to take as an example the historical Jewish women heroines.[29] Schenirer subsequently wrote a dramatization of the story of Judith for girls.[30]

Starting on December 13, 1920, after Schenirer and her students staged the play in the Orthodox Warsaw Ḥavazelet high school during a visit there, the published version was advertised on the front page of the Warsaw daily newspaper of Agudath Yisrael, Der Yud, for several weeks (first as the most beautiful present for “children” and later as a present for “girls”).

However, the above illustration of the young woman did not appear in the Bais Yaakov Journal or in any other Polish Agudath Yisrael publication. The illustrator for the Viennese publication was apparently unaware of the modesty requirements in the Polish Bais Yaakov movement, especially the style of the dress and the length of the sleeves. In illustrations of women and girls appearing in textbooks for school age Bais Yaakov students, the women were portrayed with long sleeves reaching the wrist.[31]

* * *

To sum up: we began by mentioning that Birnbaum’s illustration of the young man holding the Torah scroll appears prominently in recent academic forums where Bais Yaakov is discussed.[32] We have claimed that this illustration was neither appropriated nor used by the Bais Yaakov movement in any of its publications. In fact, it is inconceivable that it would do so. But it is understandable why some today would like the illustration to have been of a woman, or at least be relevant to women. Such an interpretation accords nicely with the narrative in recent scholarship that Bais Yaakov provided Orthodox women in Poland, for the first time, the opportunity to have a strong connection with Torah study. The same is true of the aforementioned proposed campaign to write the Torah scroll. That interpretation bolsters the contemporary reading of the Bais Yaakov movement in interwar Poland as a movement that brought Torah to women by involving them in the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll and by teaching them classical texts and commentaries (albeit not of the Talmud) in the Kraków seminary. In various writings I have shown this reading to be mistaken.[33]

In fact, the Bais Yaakov movement was from its inception a deeply conservative movement of religious revival aimed at Polish Orthodox girls and young women, in an age when various ideologies (Zionism, Socialism, Bund, etc.) competed for their attention. Through mostly supplementary education and youth activities, the movement promoted a model of a Jewish woman that emphasized piety and modesty in dress, and that educated girls to accept with pride and joy their traditional roles as Orthodox women. This is why it enjoyed and benefited from broad rabbinic support from the outset.[34] The small number of zealous Hasidic leaders who opposed the Bais Yaakov schools did so only after Agudath Yisrael, their ideological foe, took it under its auspices. It also explains why of all the Polish and Lithuanian innovations in Orthodox Jewish female education during and after the First World War (e.g., the Warsaw Ḥavazelet high school or the girls’ Yavneh high school in Telz), Sarah Schenirer’s afternoon school in Kraków, which taught young girls prayer, strict Orthodox observance, and Biblical stories, was adopted by the Polish Agudath Yisrael as the model for the development of the Bais Yaakov school network. The Bais Yaakov teachers’ seminary provided the teachers for these schools. Schenirer, a pious woman with a burning zeal for bringing Jewish women back to Orthodoxy, played a major role as the public face of the movement, primarily as its chief promoter in the towns and Polish countryside, and as the “spiritual mother” of the movement.[35] But the portrait of her as instituting women Torah study for its own sake, or of encouraging life-long study of Torah, a portrait that accords with modern progressive sensibilities, does not stand up to sober historical inquiry.[36]

Notes

[1] The illustration appears as a frontispiece of a chapter in Naomi Seidman, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition (Liverpool: Littman Library, 2019), 226.

[2] Jüdische Presse, May 12, 113; Jüdische Presse, May 19, 120.

[3] Menorah: jüdisches Familienblatt für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Literatur, May 1924, 17. See also Der Israelit: Ein Centralorgan für das orthodoxe Judentum, October 6, 1930, 22.

[4] See the auction site here.

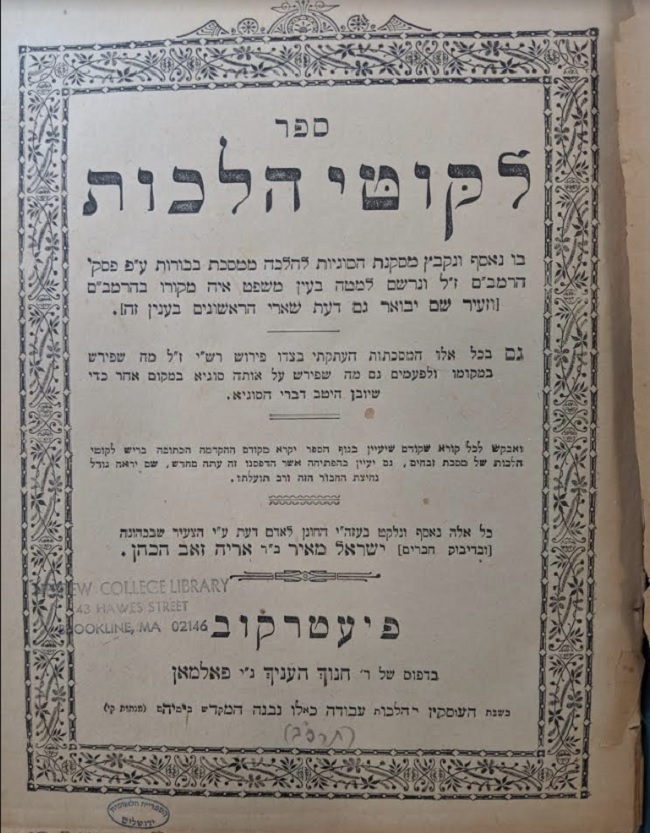

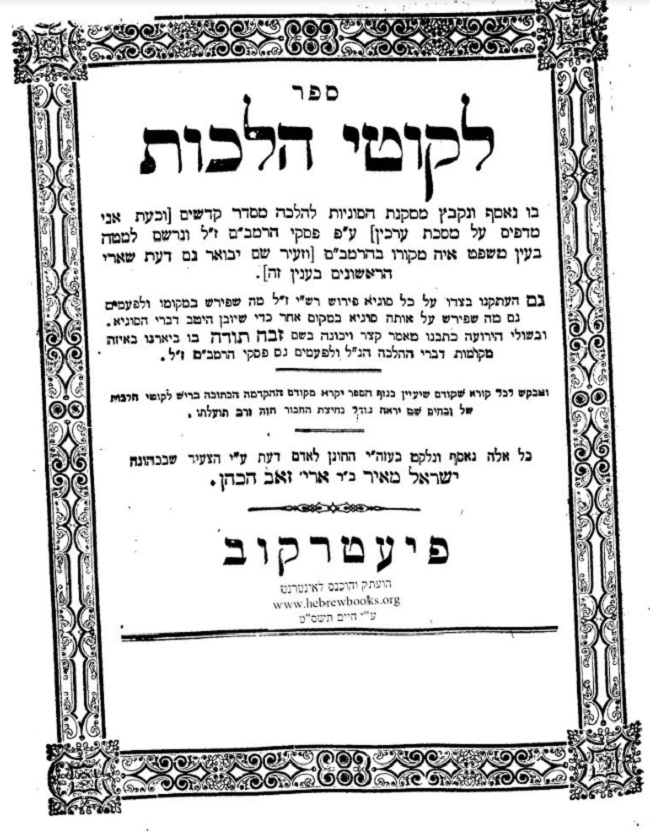

[5] Shabtai Scheinfeld (ed.), Ḥoveret shel Keren Ha- Torah, Vienna 1925, 24. For a digitized copy see https://hebrewbooks.org/43310.

[6] For a detailed discussion on this issue see Rachel Manekin, “Torah Education for Girls in the Interwar Bais Yaakov School System: A Re-Examination,” Zion, vol. 88, no. 2 (2023): 219-262, esp. 238-244, 238n71 (Hebrew). In 1929 Leo Deutschländer recounted that “just a few months” after the First Assembly, Keren ha-Torah took up its task “according to five main directions,” the fifth of which was to establish and expand the Bais Yaakov organization of schools for girls. If that is the case, then the decision of Keren Ha-Torah to support the Bais Yaakov schools was taken at its first founding meeting on December 25, 2023. But no practical steps were taken until the September 1924 meeting of the Central Council of Agudath Yisrael in Kraków.

[7] Der Israelit: Ein Centralorgan für das orthodoxe Judentum, Blätter, September 19, 1929, 2, §2c.

[8] Programm und Leistung: Keren Hathorah und Beth Jakob 1929-1937: Bericht an die dritte Kenessio Gedaulo, London/Vienna 1937, 5.

[9] See Naomi Seidman’s blog post, “When Bais Yaakov Girls Commissioned a Sefer Torah,” available here. The illustration of the youth with the sefer Torah (including the Biblical verse) accompanies the blog post giving the impression that it is part of the original 1933 article on the campaign. The following corrects inaccuracies in the blog post and adds details concerning the proposed campaign that did not come to fruition. Cf. Seidman, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement, 166.

[10] “An-eigene sefer-torah far der kolonye ‘yehudis’ vert gishribn durch di shilerins fun di beis yakov shuln in Poyln” (The ‘Yehudis’ camp’s own sefer Torah will be written through the students of the Bais Yaakov schools in Poland), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 15-16.

[11] YIVO Archives, ID: RG 120 / yarg120po705.01, “Description: Dlugosiodlo, 1920s-1930s. Boys playing chess at the Yehudia summer camp for religious children. Photographed by Leo Forbert.” The description erroneously calls the camp “Yehudia”.

[12] The Yehudis association was founded in 1928 for the purpose of religious education of girls. Among its aims it listed also the establishment of summer camps for girls from religious schools and ensuring that poor children attend school. Its organizing committee included Alexander Zusha Friedman, Yoel Unger, Yehudah Leib Orlean, and others. See “Oyfruf funem ferband far relig. yudishe techter ertsihung in varsha ‘yehudis’” (call of the association for a religious education for girls in Warsaw “Yehudis”), Der Yud, April 2, 1928, 4.

[13] “Gilaygt a yesod… fun der gruntshtayn chagigah in dlugashadle” (placing a foundation… about the cornerstone celebration in Długosiodło), Bais Yaakov 69 (1931), 2-3. Gershon Eliezer Friedenson, who wrote the article, says that when he visited the socialist Medem sanatorium five years earlier he was ashamed and jealous for not having a truly-Jewish similar institution. See also “Fayerleche grunt-shtayn leygn fun der ershter ortodoksisher zumer-kolonye ‘yehudis’ in dlugat-shadle” (the festive cornerstone placing of the first orthodox summer camp ‘Yehudis’ in Długosiodło), ibid., 14; “Der fayerliche chanukat-habayis fun der ershter ortodoksisher zumer-kolonye ‘Yehudis’” (The festive opening celebration of the first Orthodox summer-camp ‘Yehudis’), Dos Vort, June 26, 1931, 4.

[14] See the article in a Yiddish newspaper on a visit of journalists organized by the camp, “A bezuch in der chasidisher… ‘medem-sanatarye’ in dlugashadle” (A visit in the chasidic ‘Medem-sanatorium’ in Długosiodło), Unzer Białystoker Expres, January 13, 1939, 14. ‘Medem’ was the famous Tsysho sanatorium for children named after the Bundist leader Vladimir Medem. The article, which praises the camp and includes two photographs, also mentions the physical exercises as well as the play and the songs performed by the girls for the journalists. See also the photographs published in the art section supplement, Forverts, March 26, 1939.

[15] A[lexander] Z[usha] Friedman, “Di arbit far der zumer kolonye ‘Yehudis” in licht fun tsifern” (the work for the summer camp ‘Yehudis’ in light of numbers), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 9-11.

[16] An article by Unger written after the camp was built lists the rooms in the building in the following manner: six rooms for sleeping, a dining hall, an office, a lounge for the [female] teachers, an isolation room [for the sick], two washrooms, pantry, kitchen with separate facilities for milk and meat dishes, wardrobe room, porches, “etc.” Had there been a synagogue in the building it would have certainly been listed. see Yoel Unger, “Fir yohr ‘yehudis’ arbit” (four years of the ‘Yehudis” work), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 5-6, especially 6.

[17] Esther Goldshtof, “Dos leben oyf unzere kolonye” (the life in our camp), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 8.

[18] The deficit in the summer of 1933 amounted to 8,000 zloty, and in addition the camp needed to complete things like running water and electricity, see A[lexander] Z[usha] Friedman, “Di arbit far der zumer kolonye ‘yehudis” in licht fun tsifern” (the work for the summer camp ‘Yehudis’ in light of numbers), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 11.

[19] Twenty-five children paid full tuition in 1931 and 100 in 1932. 310 children received a discount in 1931 and 180 in 1932 while 55 children went for free in 1931 and 75 in 1932, ibid., 9-10.

[20] “Der fayerlicher chanukat-habayit fun der ershter ortodoksisher zumer-kolonye ‘yehudis’” (the festive dedication celebration of the first Orthodox summer camp ‘Yehudis’), Dos Yudishe Togblat, June 22, 1931, 5.

[21] “Reshimeh fun menadvim letovas der ‘yehudis’ kolonye in dlugashadle”, (a list of contributors for the benefit of ‘Yehudis’ camp in Długosiodło), Bais Yaakov 104 (1933), 15-16.

[22] For the mitzvah obligating individuals to write a sefer Torah and the question whether it applies also to women see the article by R. Eliezer Melamed, available here; and the sources presented by Barry Gelman, here.

[23] This mitzvah is not about the laws of the Torah scribe or about the mechanisms of inscribing a Torah, but rather about the mitzvah that applies to each individual Jew.

[24] A[braham] M[ordechai] Rogovy, “Di heyntige hatcholah (tsu di shloyshim fun froy scheniere a”h) (Todays beginning: at the shloshim of Mrs. Schenirer, may she rest in peace), Dos Yudishe Togblat 169, April 2, 1935, 3; “A brief fun Sarah Schenirer a”h tsu di Bais Yaakov kinder vegen koyfn otiyos in der sefer-Torah far der ‘yehudis’ kolonye (A letter from Sarah Schenirer, may she rest in peace, to the Bais Yaakov children regarding buying letters in the Torah scroll for the Yehudis camp), Ibid., 6. The issue number is different on every page, but the correct date and issue number is as written on the front page.

[25] According to the “Sha’agat Aryeh” there is no reason to exempt women, see Aryeh Leib Gintsburg, Sha’agat Aryeh, 69-70 (https://hebrewbooks.org/14616), but his is a minority opinion.

[26] Programm und Leistung: Keren Hathorah und Beth Jakob 1929-1937: Bericht an die dritte Kenessio Gedaulo, London/Vienna 1937, 295.

[27] L[eo] Deutschländer, Tätigkeitsbericht der Beth Jacob Zentrale, Vienna 1935.

[28] On Judith, see Kevin R. Brine at al. (eds.) The Sword of Judith: Judith Studies across the Disciplines, open access, 2010, especially chapter 2, “The Jewish Textual Traditions” by Deborah Levin Gera.

[29] Sarah Schenirer, Gezamelte Shriftn, New York 1955, 9. This is the American edition (with some corrections to the original Polish 1933 edition) available online, see https://hebrewbooks.org/41613.

[30] The image below comes from the Moreshet auction house, which can be accessed here.

[31] See Eliezer Gershon Friedenson at al., Yiddish loshn: ilustrirte alef-bais un layen-buch far ershtn shul-yor, Lodz 1933.

[32] Cf. the website of the 2023 international conference on Bais Yaakov held at the University of Toronto, available here. The illustration also adorns the cover of the conference program, available here.

[33] See, for example, Manekin, “Torah Education for Girls.”

[34] The claim that Bais Yaakov was “controversial among the Orthodox at the outset,” and that Schenirer herself aroused orthodox opposition initially, is made among others by Seidman, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement, 5; its basis is the author’s interpretation of a story circulating in Bais Yaakov when she was a student there: “When she [Schenirer] would walk around the towns of Poland in her efforts to found Bais Yaakov schools, Jewish boys would throw stones at her. She would bend down, pick up the stones, and say to her assailants, ‘From these stones will I build my school.’”

According to Seidman’s interpretation of the story, Schenirer “was seen by some in the Orthodox community as a dangerous innovator, and had thus faced opposition (stones), which she turned into support (schools).” Seidman cites for this E. G. Friedenson’s 1936 children’s anthology about Schenirer, Di mamis tsavoah: Zaml-buch far kinder un yugnt (The Mother’s Last Will: An Anthology for Children and Youth), 35-36. However, the story in Friedenson, which appears in the chapter on “Stories and Bon Mots” (mayselach un gute verter) and not in the chapter on “Life and Deeds,” differs significantly: “Mrs. Schenirer once visited a shtetl accompanied by its teacher. At that time, the idea of Bais Yaakov was not yet well known and fully developed as today, and its leaders and teachers were mocked at. When Sarah Schenirer had arrived in the city, a few young rascals (לאבוזיס; the Yiddish term comes from the Polish łobuz, ‘rogue’. See also Alexander Harkavy’s Yiddish dictionary for לאבוסעס) threw stones into [the classroom] (איר ארײַנגיווארפן) and one stone hit the teacher who, because of this, felt upset. We will have not just one stone – Schenirer said with a smile – they will throw stones and we will build with the stones our Bais Yaakov.” For a Hebrew translation see Em be-Yisrael, vol. 2, Yechezkel Rotenberg (ed.), Bnei Berak 1960, 41-42.

The story, apparently the first time to appear in print, and which may or may not have any basis in fact, refers to one incident in which ignorant rascals threw stones into somewhere, presumably, the school, and struck a teacher – providing Schenirer in the story with an occasion for a bon mot. Decades later, the story appears to have morphed into a tale of “violent opponents” throwing stones at Sarah Schenirer herself. See Chava Weinberg Pincus, “An American in Cracow,” in Daughters of Destiny: Women who Revolutionized Jewish Life and Torah Education, compiled by Devora Rubin, Brooklyn 1988, 189-208, esp. 200: “It was her courage and idealism that made her pick up the rocks thrown at her by violent opponents to Bais Yaakov. Rocks in hand, she would turn to her talmidos saying, ‘We will take these rocks and turn them into bricks with which we will build Bais Yaakow’.” See Shoshanah Bechhofer, “Identity and Educational Mission of Bais Yaakov Schools: The Structuration of an Organizational Field as the Unfolding of Discursive Logics,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Northwestern University, 2005, 121-122.

Clearly, לאבוזיס are not simply “Jewish boys,” nor can they represent Orthodox opposition to Schenirer as a “dangerous innovator,” since such opposition to her did not exist, even among the zealots who opposed Bais Yaakov as an Agudah project.

[35] Schenirer’s travel to towns throughout Poland was aimed to convince local Agudah ‘askanim to spend the money needed to open an afternoon Bais Yaakov school (housing and salary for the teacher, an appropriate space for the school, school expenses, etc.), as well as to convince parents to send their daughters to the school. As described in Yehudah Leib Orlean’s eulogy after Schenirer’s death, convincing ‘askanim was not always easy, although the people felt for her and the gedolei yisroel understood her, both placing their greatest trust in her. See Bais Yaakov journal 125 (1935), 6, and in Hebrew translation Em be-Yisrael, vol. 3, 49-50. According to Schenirer, many parents did not understand the importance of the Bais Yaakov education or were satisfied with sending their daughters to the school for one year, just enough for them to learn to pray and write in Yiddish. Even then, girls were occasionally late or missed school with all kinds of excuses. Other parents thought it was too difficult to attend two schools. See Sarah Schenirer, Tsu vos darf men Bais Yaakov shulen? Populare agitatsye-broshur far’n Bais-Yaakov-gedank )’Why Does One Need Bais Yaakov Schools? A Popular Agitation Brochure for the Bais Yaakov idea’), Warsaw 1933, 25-31. The brochure includes a proclamation by Agudath ha-Rabbanim signed by many rabbis (among them Ḥayim Ozer Grodzinski, Zalman Sorotzkin, and Aharon Walkin) calling parents not to send their daughters to Jewish secular schools, which were “akin to Molekh” (e.g., the Tarbut schools), but rather to Bais Yaakov. Clearly, such an endorsement was needed not to support Schenirer herself, but rather to convince parents of the importance of sending their daughters to Bais Yaakov. It should be noted that annual statistics of Bais Yaakov students do not take into account the number of years they attended the school.

[36] See Manekin, “Torah Education for Girls.” The memorial issue of the Bais Yaakov journal published after Schenirer’s death which includes about three dozen articles about her written by different personalities and students, praised her dedication, idealism, enthusiasm, piety, warmth, charity, modesty, and teaching yidishkeit rather than her learning or teaching Torah, something that was not even mentioned. One of the articles emphasized her simplicity (פשטות), explaining that “when she decided to devote her efforts to the education of girls, she did not make herself important as dealing with the problems of the education of daughters, did not aggrandize her mission, did not try to win personalities for her plan; in general, she avoided any advertisement or propaganda noise, but rather simply sat down to learn yidishkeit with children with seriousness and honesty, so her path did not only not arouse opposition (because of the fear of teaching girls Torah etc.), but on the contrary, it only aroused great satisfaction and approval of all circles.” See A. Y. Lipmanovitch, “Der Koyech fun Pashtus” (the power of simplicity), Bais Yaakov 125 (Iyar/Sivan 1935), 18.