Kalir, False Accusations, and More

by Marc B. Shapiro

1. I now want to return to Kalir and the criticism of me. To recap, I had earlier mentioned how Artscroll originally correctly identified Kalir as post-tannaitic, but later changed what it wrote in order to be in line with Tosafot’s opinion that he was a tanna. Some think that it is wrong to criticize Artscroll by using academic methodology instead of judging them by traditional sources, since they don’t recognize the academic approach.

My first response is that this is nonsense and a textbook example of obscurantism. If there is evidence of a certain fact, one can’t say that it is only a fact if it appears in some “traditional” source, and therefore one who ignores this evidence gets a pass.

Furthermore, when it comes to Kalir one can also date him using traditional sources.

[1] One of these sources is quite fascinating. Whether there is any truth to the event described, I can’t say, but the fact that a traditional source dates him after the tannaitic era is what is important for us at present. This shows that Tosafot’s dating is not the only traditional source in this matter. The source I refer to is the medieval R. Ephraim of Bonn who states that the paytan Yannai, who is usually dated to the seventh century but could even be a few centuries earlier (but still post-tannaitic), was the teacher of Kalir.

R. Ephraim notes that Yannai was not the most kind of teachers and he was jealous of his student Kalir, showing that the Sages’ statement that people are jealous of all, except for a son and student (Sanhedrin 105b), can have exceptions. In order to deal with his problem, Yannai decided to terminate Kalir, with extreme prejudice of course. He therefore put a scorpion in Kalir’s sandal which took care of matters. R. Ephraim reports that because of this murder, in Lombardy (Italy) they refused to recite one of Yannai’s hymns.

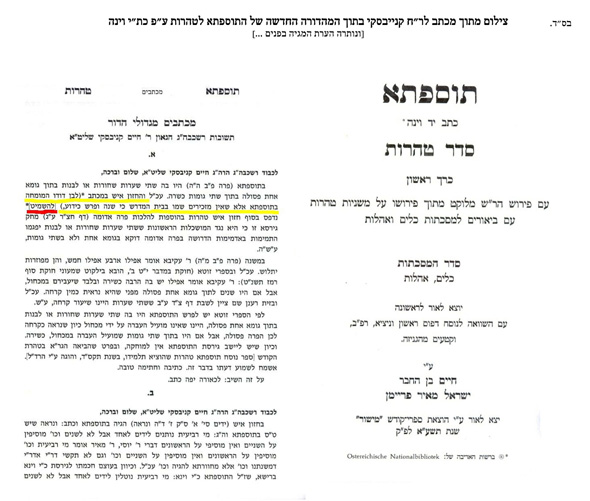

[2]

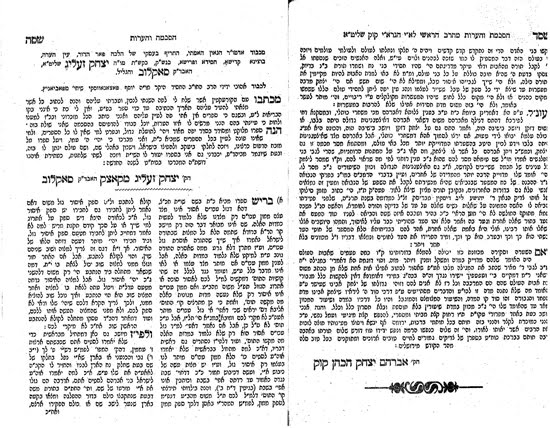

אוני פטרי רחמתים. ואמר העולם שהוא יסוד ר’ יניי רבו של רבי אלעזר בר קליר, אבל בכל ארץ לומברדיאה אין אומרים אותו, כי אומרים עליו שנתקנא בר’ אלעזר תלמידו והטיל לו עקרב במנעלו והרגו. יסלח ה’ לכל האומרין עליו אם לא כן היה.

R. Ephraim is the source for this report and as you can see from his final words, he took the report very seriously and literally, declaring that if it wasn’t true then those who spread this rumor were in need of repentance. Israel Davidson, however, claims that to take the report literally would be “absurd”, and the report of the scorpion is merely an “idiom, undoubtedly Oriental in origin, for expressing unfriendliness.”

[3] The problem with this is, as we have seen, R. Ephraim and the community of Lombardy

did take the report literally, so why should Davidson, living well over a thousand years after the supposed event, know more than people who lived in medieval times?

[4] It is one thing to say that the murder never occurred, but that doesn’t mean that the story as told was not meant to be understood literally, and there is every reason to assume that it means what it says. If it happened, it would hardly be the first murder committed by a Jew. Thus, although the story is almost certainly a legend, our reason for making this determination is not because it is impossible to imagine one Jew doing such a thing to another.

Another important source is found in R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai,

Mahazik Berakhah, Orah Hayyim 112 (end). Azulai, as we all (should) know, had a keen bibliographical sense, and knew rabbinic history very well. After mentioning how Tosafot and the Rosh state that Kalir was really the tanna R. Eleazar ben Shimon,

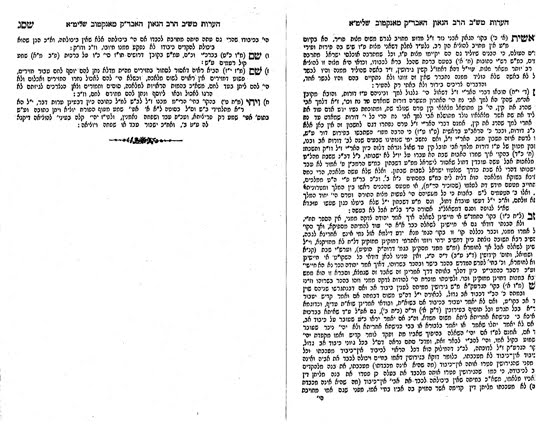

[5] the Hida quotes R. Isaac Luria as follows:

דהפייטן היה בו ניצוץ מנשמת ר’ אלעזר ברבי שמעון.

In other words, it is not that Kalir was actually a tanna, but that his soul was connected with R. Eleazar ben Shimon. I presume that this is an attempt to preserve the old tradition identifying the two, while at the same time recognizing that historically they were two different people. We find the same approach among many commentaries that deal with aggadic statements that make all sorts of identifications, of what can perhaps be called the rabbinic “conservation of people.” In other words, there is a tendency to identify biblical figures with other known biblical figures, such as Elijah with Pinhas and Harbonah, Hagar with Keturah, Pharaoh with the King of Nineveh, Yocheved and Miriam with Shifrah and Puah, Mordechai with Malachi

[6] and Ezra, Tziporah with the Cushite woman,

[7] Balaam with Laban, Daniel and Haman with Memukhan, to mention just a few.

[8]

I don’t think people should be surprised that also among traditional commentators one can find the viewpoint that these identifications are not to be taken literally

[9]—kabbalists are often inclined to see these texts as referring to reincarnation

[10]—and some modern scholars have spoken of these identifications as examples of what they term “rabbinic fancy.” Some of these identifications are so far-fetched that I have no doubt that R. Azariah de Rossi and R. Zvi Hirsch Chajes are correct that the Sages who expounded them never intended them to be taken literally.

[11] Although I haven’t investigated the matter, I assume one would find the same tendency to non-literal interpretation when dealing with Aggadot that insert historical figures into other biblical episodes, e.g., Balaam and Jethro becoming Pharoah’s advisors, or when the Aggadah identifies spouses, e.g., Caleb marrying Miriam and Rahab marrying Joshua (and having daughters with him

[12]).

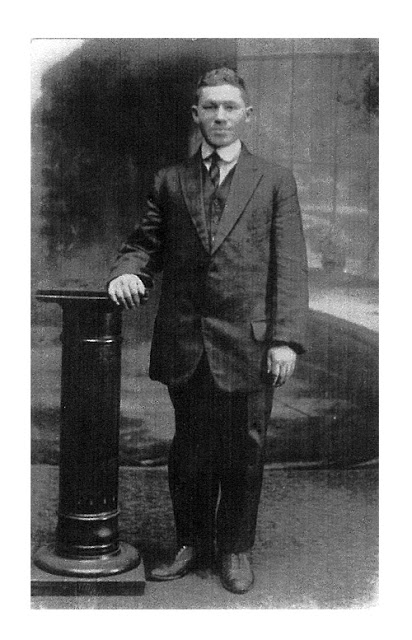

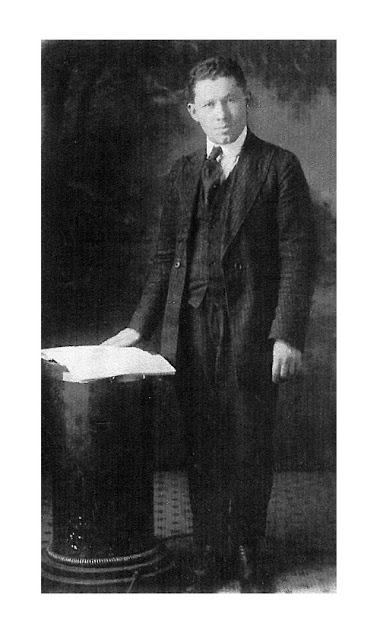

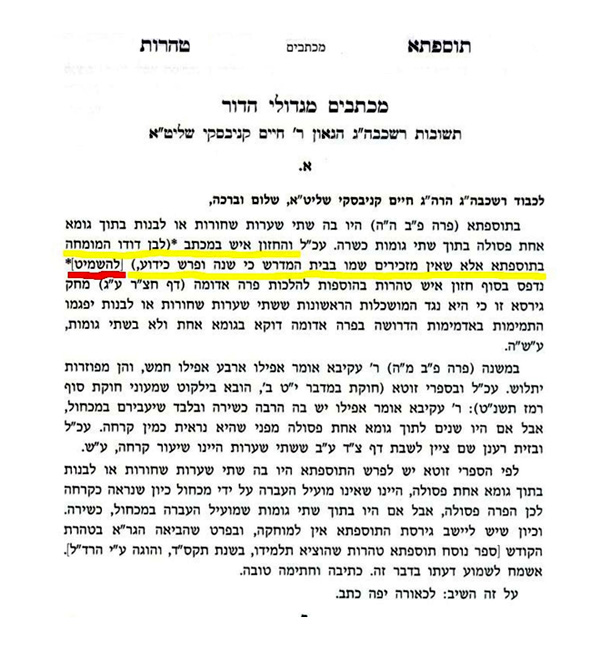

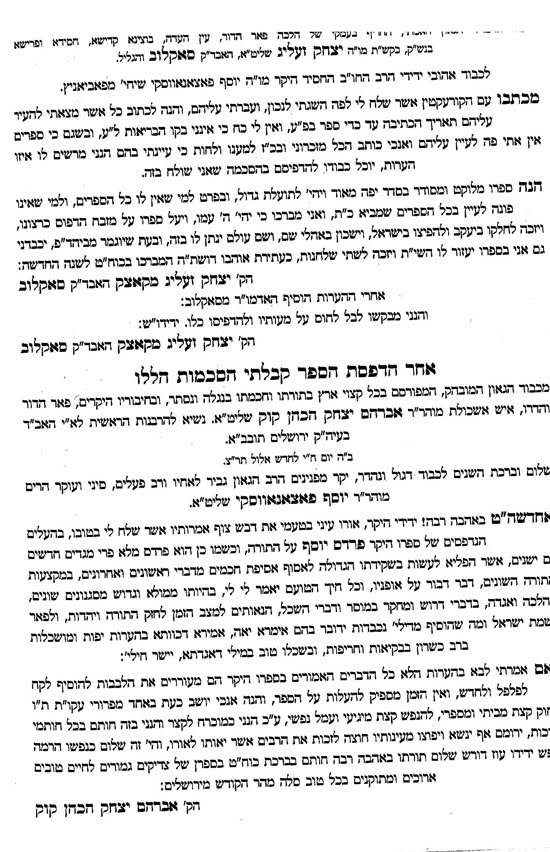

2. In the previous post I quoted what the late R. David Zvi Hillman said in the name of R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin regarding Saul Lieberman. Some people were incredulous, and this raises the question of how reliable Hillman was and if he would distort things for ideological purposes.

[13] I have spoken about him before, and I reproduced his defense of the Frankel edition of the

Mishneh Torah not citing R. Kook.

[14] Despite his strong ideological leanings, as of yet I haven’t found any evidence that he would purposely distort. My sense is that he was quite honest in his scholarship (and the issue with R. Zevin and Lieberman might have been something he misunderstood or perhaps R. Zevin wasn’t clear in what he said. It simply is impossible now to reconstruct events.)

Even though I believe that Hillman was honest in his scholarship (i.e., not intentionally distorting as is so often the case with haredi writers), we do find that his ideology led him to unfounded conclusions. These are not intentional distortions because he really believed what he was saying, but they are distortions nonetheless. Here is one example.

In 1999 a memorial volume appeared called

Ohel Sarah Leah. Beginning on p. 246 is an article by Hillman dealing with R. Joseph Saul Nathanson’s view of the International Date Line. In this article, he deals with a letter by R. Zvi Pesah Frank published by R. Menachem M. Kasher. He believes that Kasher added material to the letter so as to align it with his own viewpoint. The fact that Kasher published the letter in 1954, almost seven years before R. Zvi Pesah Frank’s death, does not deter Hillman from his argument. Other than Hillman, I think everyone realizes that if you are going to forge something in another’s name, you don’t do it when they are still alive!

[15] We can thus completely discount Hillman’s argument and see it as an ideologically based distortion.

Despite this defense of Kasher, it must also be pointed out that there are serious questions about the reliability of some things he published. In Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy I mentioned R. Eliezer Berkovits’ claim that the Weinberg letter Kasher published was not authentic. Berkovits clearly thought that Kasher forged it, but when I pressed him to say so openly, he wouldn’t. All Berkovits would say is that Weinberg never wrote such a letter, and it was fraudulent. When I asked, “So R. Kasher forged it?” he replied that he wasn’t going to speculate about this, and would only say that the letter did not exist. Being that Kasher claimed that Weinberg wrote the letter to him, this means that Berkovits was accusing him of forgery, but for whatever reason did not want to say so openly.

I have a 1982 letter from Berkovits to another rabbi, and in this letter he is not as circumspect as he was with me. Here he pretty much states that Kasher forged the letter “le-shem shamayim.”

בענין מו”ר הגאון זצ”ל אני בטוח שהוא מעולם לא כתב אותם הדברים שהרב כשר מוסר בשמו בנועם. אדרבה יראה לנו את מכתבו של מו”ר זצ”ל. לפני כשנה כתבתי לו בדואר רשום ובקשתי בעד צילום או העתק של מכתבו של הרב וויינברג זצ”ל. עד היום לא קבלתי תשובה ממנו. מבטחני שהדברים שנאמרו ושנכתבו בשמו אינם אמיתייים. בעונותינו הרבים הגענו למצב שגם אנשים ירא שמים וכו’ מורים היתר לעצמם בכל מיני ענינים כשהם חושבים שכל כוונתם לשם שמים היא. והוא רחום יכפר וכו’.

In the recently published Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish, pp. 263ff. the unnamed editor also levels serious accusations against Kasher, in a chapter entitled הזיוף החמור והנורא. He puts forth a series of claims designed to show that another letter Kasher published on the International Date Line, this time a posthumous letter from R. Isser Zalman Meltzer, is also forged. I have to say that in this example, unlike the one dealt with by Hillman, there is at least circumstantial evidence, but no smoking gun. The most powerful proof comes from Kasher himself in which he tells of a meeting with the Hazon Ish and how at that meeting he told the Hazon Ish about the letter he received from R. Isser Zalman in opposition to the Hazon Ish’s position. Yet the letter Kasher publishes from R. Isser Zalman is dated from after the Hazon Ish’s death. There is clearly a problem here, but more likely than assuming forgery is that Kasher was simply mistaken in his description of his visit with the Hazon Ish. Let’s not forget that this element of the account of his visit was published thirty-three years after the event, and it is possible that Kasher didn’t recall everything that was said. The followers of the Hazon Ish have indeed always claimed that his description of his visit, in Ha-Kav ha-Ta’arikh ha-Yisraeli (Jerusalem, 1977), pp. 13-14, is not to be relied upon. Since his own recollection of his visit is the strongest evidence in favor of Kasher forging R. Isser Zalman’s letter, it is not very convincing.

In the previous paragraph I wrote that “this element” of Kasher’s account was published thirty-three years after his visit, so let me explain by what I mean by that. In Ha-Pardes, Shevat 5714, p. 30, soon after the Hazon Ish’s death, he originally published his account. Only when he later published his Kav ha-Ta’arikh ha-Yisraeli did he mention that he told the Hazon Ish that he received letters from R. Zvi Pesah and R. Isser Zalman, and this point is mentioned after his description of his visit. In his original description he mentions nothing about receiving letters, only that R. Zvi Pesah told him his opinion and R. Isser Zalman agreed with this. I think what likely happened is that in the passing decades Kasher forgot that the letters he received only arrived after the Hazon Ish’s death. As mentioned, if you look at what he wrote right after the death of the Hazon Ish, he doesn’t mention any letters, and he even states explicitly that he didn’t have anything in print from R. Zvi Pesah. I think this shows that while Kasher’s recollection was not exact, there is no evidence that he forged the letter.

I do, however, have to mention that in the 1977 version of the visit Kasher adds something that is not in the original recollection and must therefore be called into question. In the original recollection he reports that the Hazon Ish began reading Kasher’s work on the dateline and then said that he is tired and asked if he could hold on to the work to read later. In the 1977 version Kasher then adds the following, which shows the Hazon Ish as not very committed to his own position, a point which is at odds with everything else we know about the Hazon Ish and the dateline:

והוסיף בזה הלשון: נו, יעדער מעג (קען) זיך האלטען ווי ער פערשטעהט. [כל אחד רשאי (יכול) להחזיק כפי הבנתו].

Kasher was also involved in another problematic episode related to his book Ha-Tekufah ha-Gedolah, which is dedicated to showing the messianic significance of the State of Israel. In the book, pp. 374ff., he includes a proclamation urging participation in the Israeli elections. This proclamation is signed my many rabbinic greats and states that the State of Israel is the beginning of the redemption. This is a very significant document and is often referred to, because among the signatories are some who were never identified with Religious Zionism.

But is the document authentic? Zvi Weinman has shown (and provided the visual evidence) that a number of the rabbis signed a document that did not mention anything about

athalta di-geula but instead referred to

kibutz galuyot.

[16] In Kasher’s book, their names are listed together with those who signed the document referring to

athalta di-geula, even though they never agreed with this formulation. This would appear to be a Religious Zionist forgery (unless it is simply a careless error), although it is impossible to know whether Kasher was responsible for this or if he was misled by someone else.

If it can ever be proven that Kasher was indeed responsible for a forgery, there is still a possible limud zekhut for this type of behavior (and I mentioned it in a prior post): If you are convinced of the correctness of your position, it is not hard to construct an argument, based on traditional Jewish sources, that false attribution and even forgery is permissible. In the book I am currently working on I bring all sorts of examples of this which I think will be very distressing for readers, as it is in complete opposition to what most of us regard as basic intellectual honesty.

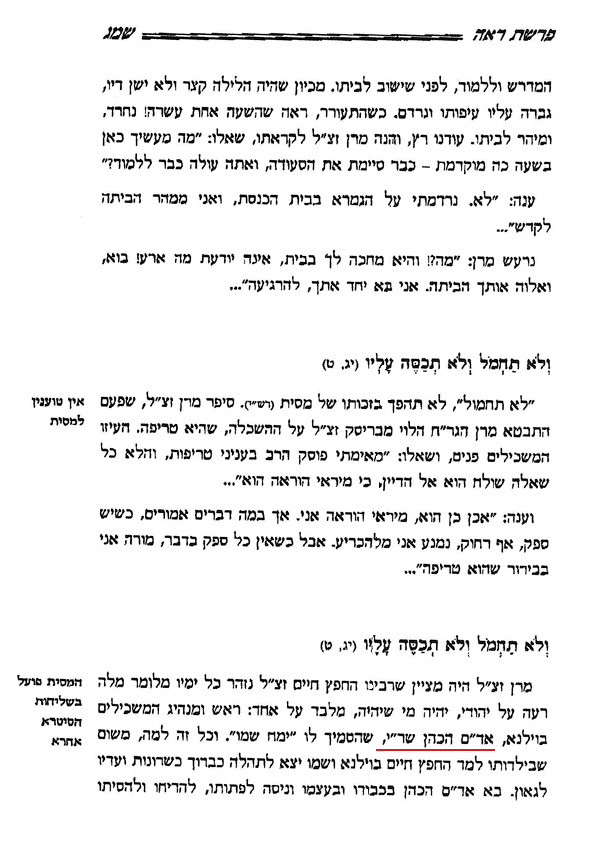

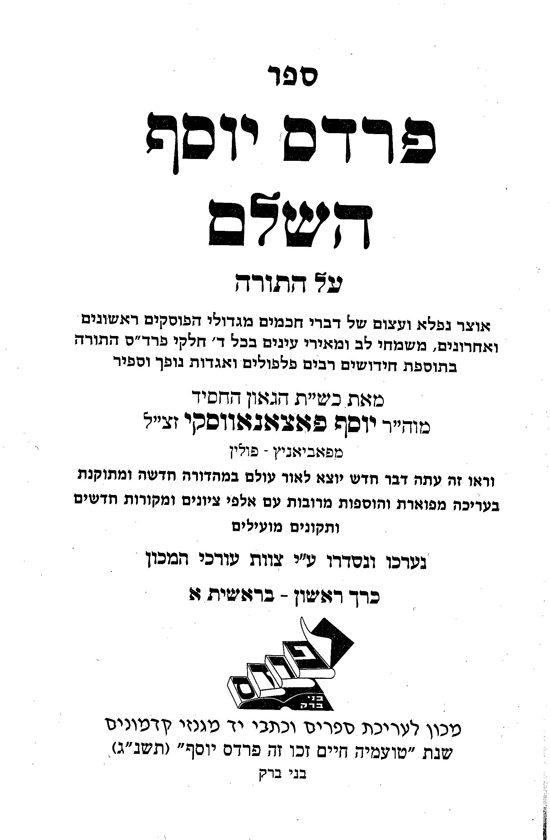

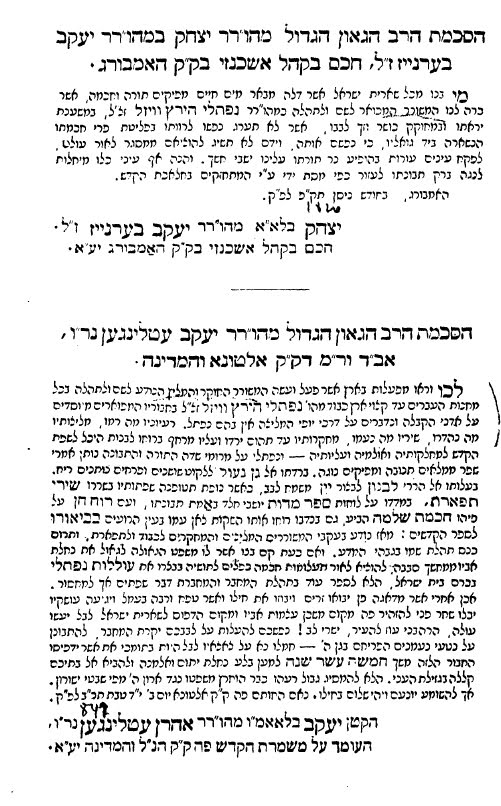

Returning to the recently published

Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish, the editor also makes an outrageous accusation and I am surprised that no one has yet publicly protested. The canard is leveled at Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog, whose saintliness was universally acknowledged even by those who opposed his Zionist outlook. It was R. Herzog who in early 1940 flew to London and was able to convince the English government to grant a number of visas for Torah scholars. He was thus directly responsible for saving the lives of, among many others, R. Velvel Soloveitchik and R. Shakh.

[17] This fact alone should have been enough to prevent any scurillous accusations directed against R. Herzog.

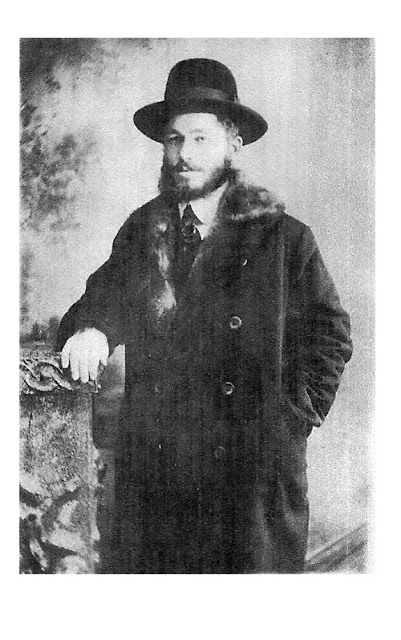

On pp. 226ff. there appears a 1941 letter, dated 24 Elul, from R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin to the Hazon Ish asking him about the problem of Shabbat in Japan for those who had escaped the Nazi clutches. R. Zevin wrote to the Hazon Ish at the request of R. Herzog, who said that only two people in the Land of Israel were expert in this matter, R. Tukatchinzky and the Hazon Ish.

There is a good deal that can be said about R. Zevin’s letter and the Hazon Ish’s response, but that is not my concern at present. Yet I must at least mention that the editor provides another letter from the Hazon Ish in which he expresses his displeasure that R. Zevin’s Torah writings had appeared in the newspaper Ha-Tzofeh. According to the Hazon Ish, these should have been published as a special booklet, as it is inappropriate to publish Torah articles in a newspaper that in the end is used to wrap food in. He also mentions that Ha-Tzofeh itself is not suitable, referring obviously to its Religious Zionist outlook. (R. Zevin would, over his lifetime, write hundreds of articles for Ha-Tzofeh, many of which have not yet been collected in book form.)

Also noteworthy is that in his reply to R. Zevin the Hazon Ish raises the possibility that the viewpoint of the rishonim would have to be rejected if it turns out that they were mistaken in their understanding of the metziut.

העומד עדיין על הפרק הוא אם טעם הראשונים ז”ל הוסד על המחשבה שאין ישוב בתחתית הכדור, ואז נקח עמידה נועזה לנטות מהוראת רבותינו ז”ל ולעשות למעשה היפוך דבריהם הקדושים לנו ולכל ישראל, או שאין לדבריהם שום זיקה לשאלת ישוב התחתון.

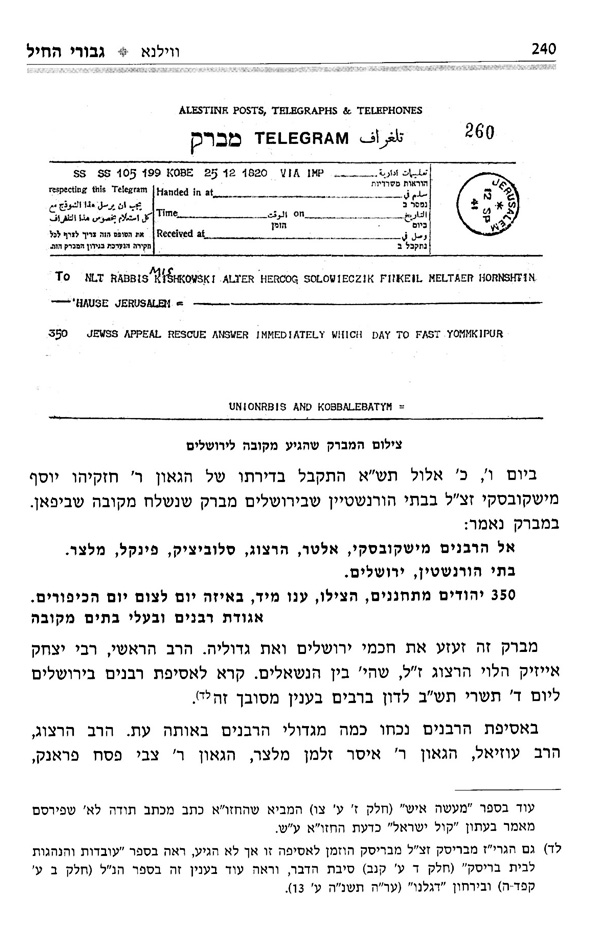

(In a later letter, quoted on p. 231, we see a different perspective.) In R. Zevin’s letter he mentions why the issue of Shabbat in Japan was so pressing. R. Herzog had recently received a telegram from Kobe, Japan, asking on what day the Jewish refugees should fast.

[18] Here is a copy of the telegram, as it appears in David A. Mandelbaum’s

Giborei ha-Hayil, vol. 1.

Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish, p. 227, makes the astounding assertion that this telegram was a scheme cooked up by the Chief Rabbinate (i.e., R. Herzog).This would enable R. Herzog to call a gathering a great Torah scholars at which time he could push them to accept his opinion in opposition to the viewpoint of the “gedolei Yisrael.” It is hard to imagine a more outrageous accusation directed against a man of unquestioned piety such as R. Herzog.

Quite apart from the slander I have just pointed to, the volume also contains a good deal of ideologically based distortion, which is why it is noteworthy that it not only includes the letter from the Hazon Ish to Saul Lieberman (p. 330) that I published in

Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox,,

[19] but even identifies him in the following respectful way:

המכתב נשלח לבן דודו פרופ’ ר’ שאול ליברמן ז”ל מחה”ס תוספתא כפשוטה, ירושלמי כפשוטו וש”ס.

Considering how Lieberman is

persona non grata in the haredi world, I find this identification, as well as mention of his books, nothing sort of remarkable.

[20]

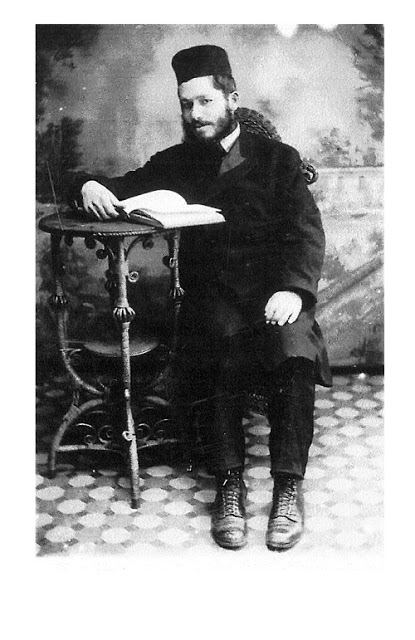

In fact, the story gets even more interesting. A couple of months ago volume two of

Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish appeared. Before I was able to get a copy, people emailed me to let me know that this volume contained a lengthy letter from Lieberman to the Hazon Ish. (I thank Ariel Fuss for sending me a copy of the letter.) It appears on pages 207-209 and is really fascinating. Leaving aside the talmudic analysis, the end of the letter shows the different outlooks of these cousins. We see that the Hazon Ish had criticized Lieberman for referring to Prof. Jacob Nahum Epstein as mori ve-rabbi. Lieberman didn’t understand why the Hazon Ish found this objectionable, since Epstein was a pious Jew and Lieberman learnt many things from him, “true Torah and not the path of the maskilim but that of our teachers of blessed memory, who search for the truth in the words of Hazal, in all possible ways, and many obscure places in the Jerusalem Talmud were explained to me precisely through this approach.”

[21]

Lieberman then turns to another criticism of him by the Hazon Ish, that he was not devoting himself adequately to his Torah study. It is hard to know what to make of this critique, as who was more devoted to his studies than Lieberman. Lieberman defends himself from this accusation, noting:

אני לפעמים נופל על הספסל מחוסר אונים מרוב התאמצות ויושב אני לפעמים כמה ימים על סוגיא אחת עם ראש חבוש.

Here is Lieberman’s grave, in the Sanhedria cemetery. Note who he is buried next to. (As I mentioned in Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, according to Chaim Herzog, Lieberman was R. Herzog’s closest friend. It is therefore fitting that he be buried next to R. Jacob David.)

3. Regarding the last post, a number of people emailed me pointing out other “immodest” title pages and also learned women that I didn’t mention. I thank all who emailed. Many of the other title pages I knew about and might refer to at a future time, but the post was specifically concerned with

censorship of title pages, and this explains the ones I cited. One of the commenters did refer to a title page that I did not know, from a 1731 Hamburg manuscript. See

here (the rest of the Haggadah has other interesting pictures). If you ever needed an example of how what we today regard as unacceptable is not necessarily how people hundreds of years ago viewed matters, this is it.

[22]

Regarding learned women, a great deal has obviously been written about this and I don’t see it as my purpose to simply repeat what others have written elsewhere. I hope that in the prior post (and indeed in all my posts), people find new material and learn things that they wouldn’t know from elsewhere, even those who are experts in the various topics.

Since the matter has been raised again, le me mention something that I originally was going to write about. At the last minute I took it out, as I was convinced (by both a scholar who will remain anonymous and Prof. Shamma Friedman) that I was in error.

Tosefta Ketubot 4:7 (and the parallel passage in J. Ketubot 5:2) reads:

נושא אדם אשה . . . על מנת שתהא זנתו ומפרנסתו ומלמדתו תורה.

It then follows by telling us that R. Joshua son of R. Akiva arranged exactly this sort of marriage. I think that if you show this passage to people, and cover up the commentaries, they will translate it to mean that a man can marry a woman on the condition that she will take care of his physical sustenance “and will teach him Torah.” (This is how Neusner translates in his Tosefta and Yerushalmi translation, and is also found in some academic articles.) Yet all of the traditional commentaries understand this text to mean that the woman provides the financial support her husband needs in order that he is able to study Torah on his own. For a while I assumed that this was an apologetic understanding by the commentators, and we know that the Talmud does offer a few examples of learned women. Yet as mentioned, I was convinced of my error.

[23] In email correspondence, Friedman also called attention to other unusual Hebrew formulations which don’t mean what they literally say. For example,

Yevamot 13:12 states: בא על יבמה גדולה תגדלנו. Yet this does not mean that she has to raise the boy, but only that she has to wait until he is of age to give her a divorce. He also pointed to

Nazir 2:6 (and see also 2:5) which uses the language of הרי עלי לגלח חצי נזיר and this has nothing to do with shaving the Nazir.

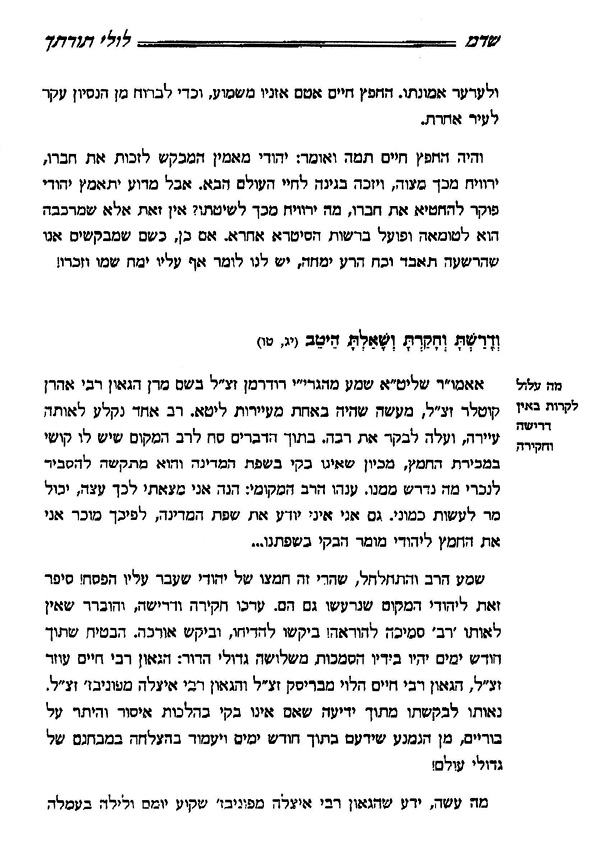

One final point I would like to make about learned women is that before drawing any conclusions about their knowledge, we must be sure that we are not dealing with ghost writers. For example, Dov Katz,

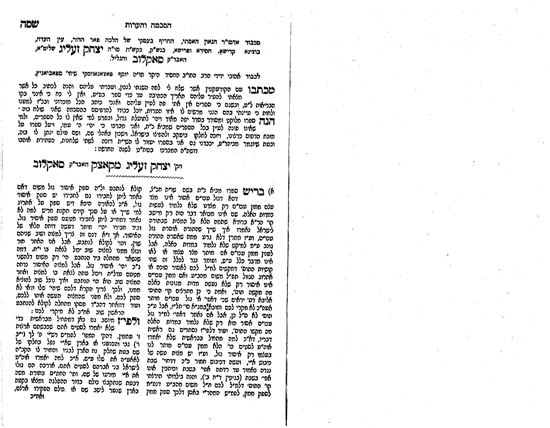

Tenuat ha-Mussar (Jerusalem, 1982), vol. 1, p. 242 n. 30, refers to the wife of R. Aryeh Leib Horowitz (the son of R. Israel Salanter) as a “learned woman” based on the introduction she wrote to her deceased husband’s

Hayyei Aryeh (Vilna, 1907). Here is the text.

I can’t prove it, but I am very confident that someone wrote this on behalf of the wife, who was a traditional rebbetzin, not a maskilah.

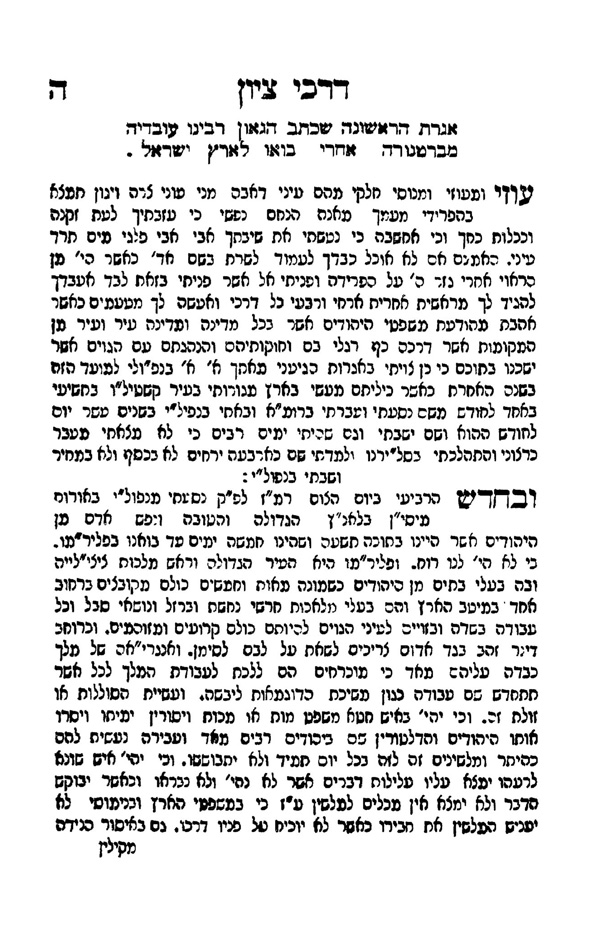

4. In preparation for the trip I am leading to Italy in July (we still have room for some more people, and also for the August trip to Central Europe), I thought it would be helpful to read the letters of R. Ovadiah Bartenura. Right at the beginning of the first letter

[24] I found something very interesting. I immediately suspected that this passage would be omitted from a translation directed towards the Orthodox masses. I checked, and lo and behold, the passage is indeed deleted. Here is the text:

Note how R. Ovadiah testifies that while the Jews in Palermo were careful about not drinking non-Jewish wine, which was noteworthy since elsewhere in Italy Jews routinely consumed this, their sexual morality and observance of the Niddah laws left something to be desired. He claims that most young women there were already pregnant at their wedding.

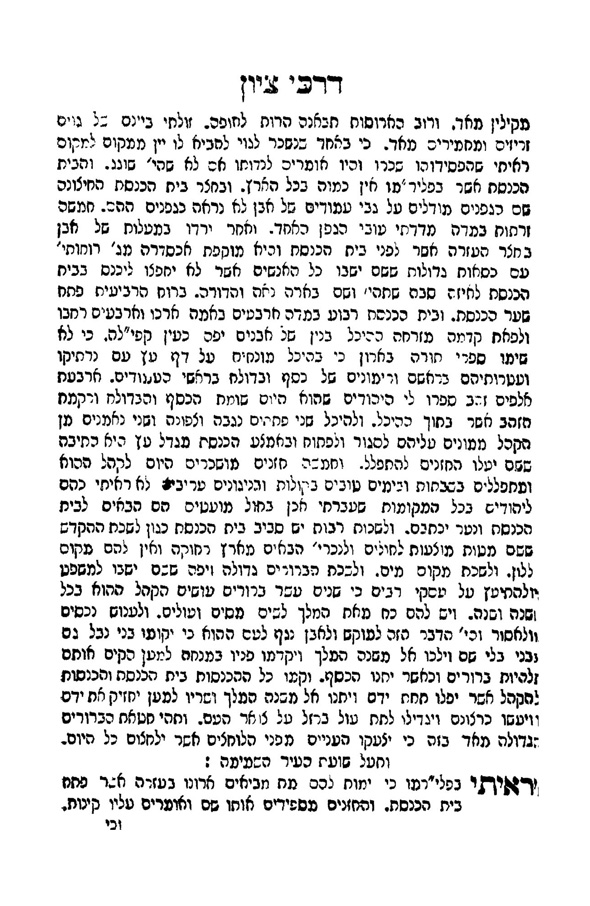

Here is how the page appears in the translation by Yaakov Dovid Shulman:

This text was censored even though the preface to the book states: “In publishing these letters in their entirety, including the critical comments made by Rabbi Ovadiah Bartenura of those people and practices of which he disapproved, the assumption is made that these criticisms were written to instruct the reader and not to denigrate any individuals.” As you can see, the letter has

not been published in its entirety, and if one were to go through the text carefully, perhaps some other deleted passages would be discovered.

[25]

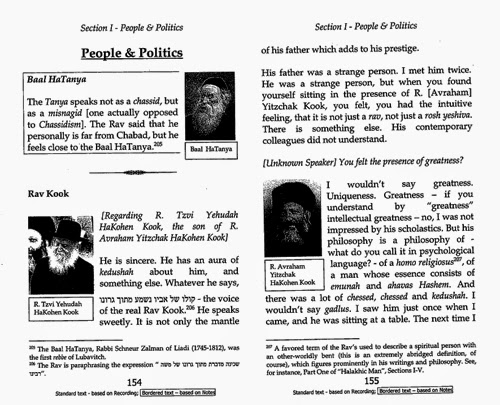

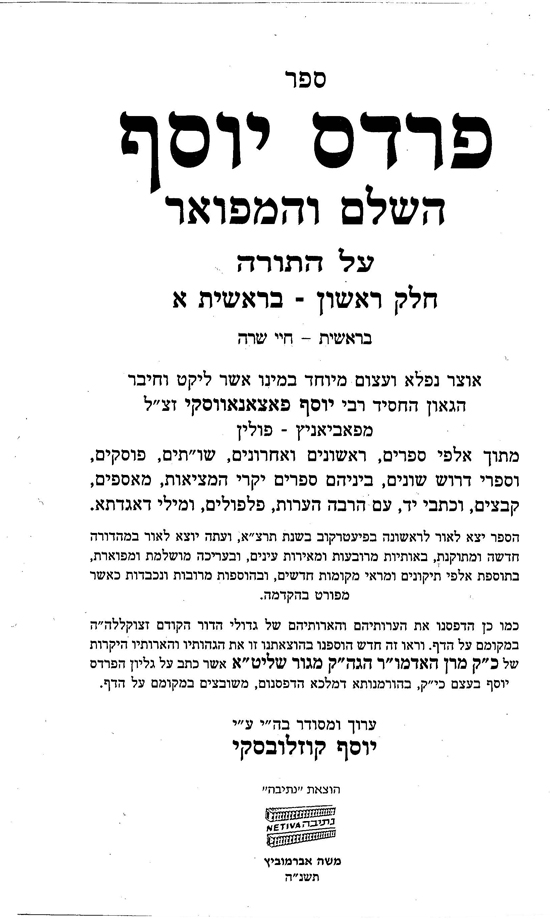

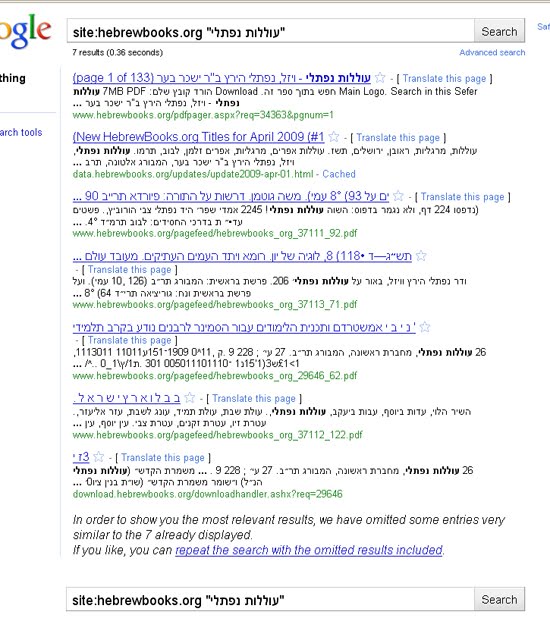

5. I have done six posts on R. Kook and from email I receive I know that some people want me to return to this. I plan to, but I still have a few more posts to do before I get to that. In the meantime, however, I want to inform readers that a new volume of R. Kook’s writings has just appeared. It is called Ginzei ha-Rav Kook and I thank R. Moshe Zuriel for drawing my attention to it. My sense is that this volume does not have much importance, as much of it, and maybe even the majority, has already appeared in other collections, particularly the Shemonah Kevatzim. I was able to determine this using the R. Kook database, which except for the most recently published material includes all of R. Kook’s writings.

I did find one passage (p. 87, no. 85) which I am pretty sure has not yet appeared, even in the most recent writings. It relates back to a point I already called attention to in R. Kook, namely, his privileging of the pious masses over the Torah scholars in certain ways. One rabbinic text that would appear to oppose R. Kook’s conception is the famous Avot 2:5: ולא עם הארץ חסיד. See how R. Kook neutralizes this text, pointing out that there are a lot of things more important than being a hasid. Here is R. Kook, a member of the rabbinic elite, nevertheless insisting that the am ha-aretz can have just as much holiness as the Torah scholar, be visited by Elijah, and even have ruah ha-kodesh:

“ולא עם הארץ חסיד”. אבל מה שהוא למעלה מהחסידות, כמו קדושה וענוה ותחית-המתים וגילוי אליהו ורוח-הקודש, מפני גודל קדושתם הם שוים לכל נפש. כי כל לבבות דורש ד’, ואחד המרבה ואחד הממעיט ובלבד שיכוון לבו לשמים, ומעיד אני עלי שמים וארץ, אמר אליהו, בין איש בין אישה, בין עבד בין שפחה, בין נכרי בין ישראל, הכל לפי מעשיו רוח הקודש שורה עליו. וכיון שלא יצאו שפחה ונכרי מכלל רוח-הקודש, קל-וחומר שלא יצא עם-הארץ שהוא מזרע קודש, מעם ה’ וצבאותיו אשר הוציא ממצרים להיות לו לעם נחלה כיום הזה, סגולה מכל העמים.

(The reference to Elijah is from Tanna de-Vei Eliyahu, ch. 9.)

P. 112, no. 104, returns to a theme I have also dealt with, that study of halakhic details can be problematic for a mystical personality such as R. Kook.

[26] Yet he adds that this is still the job of the righteous ones, and we can see here an autobiographical reflection.

אף על פי שלימודם של המצוות המעשיות בדקדוק קיומם מכביד לפעמים הרבה על הצדיקים הגדולים השרויים תמיד באור המחשבה העליונה, מכל מקום מתוך כח היראה העליונה שבלבבם, מתגברים הם גם על שפע קדושתם, ועוסקים בתורה ובמצוות במעשה ובדקדוק, אף על פי שהם צריכים למעט על ידי זה את אורם העליון.

Can we also see an autobiographical reflection on p. 114, no. 106, where R. Kook speaks about the righteous who want the world to recognize their greatness and holiness?

לפעמים מתגלה בצדיקים גדולים תשוקה גדולה, שיכירו הכל את מעלתם ושיאמינו בקדושתם. ואין תשוקה זו באה כלל משום גסות הרוח או אהבת כבוד המדומה, כי אם מפני החשק הפנימי של התפשטות האור הטוב שבהם על חוג היותר רחב האפשרי. וזהו מעין התשוקה של הופעת החכמה על ידי המצאות טובות וספרים טובים שכשהיא אידיאלית היא עומדת בנקודה היותר עליונה שבאור הנשמה הא-להית.

He then returns to the difficulty the Tzaddik has with halakhic particulars (p. 115):

ישנם צדיקים גדולים כאלה, שהם למעלה מכל שרש הדינים, ועל כן אינם יכולים ללמוד שום דבר הלכה. וכשהם מתגברים על טבעם ועוסקים בעומקא של הלכה, מתעלים למעלה גדולה לאין חקר, והם ממתקים את הדינים בשרשם.