WHAT WAS BOTHERING THE CENSOR?

by Eli Genauer

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century was a great boon for Torah study. Manuscripts which had to be laboriously copied one by one could now be set to type and hundreds could be produced at one time. One of the earliest Jewish treasures to be set to print was the Talmud. Scattered volumes of it were printed in the late 15th century and early sixteenth century, but the first complete set was printed from 1519-1523 in Venice by Daniel Bomberg. He followed this with printing two more sets, and was joined by Marco Antonio Justinian who printed a complete set from 1546-1551.

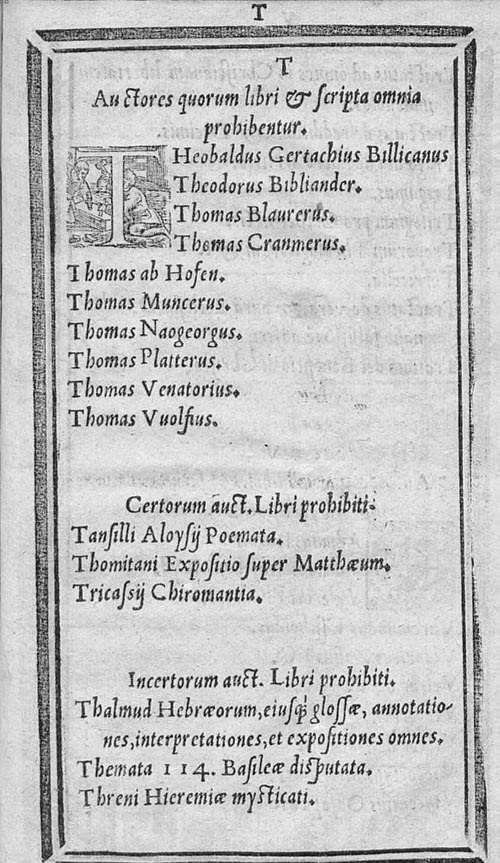

The competition between Justinian and another gentile printer named Bragadini, led to one of them denouncing the other to the Pope for printing items which were against the Church. This led to the public burning of the Talmud throughout most of Italy starting in 1553.[1] The Talmud was listed in the Church’s first

Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1559.

There still was a possibility to print the Talmud but only under the watchful eye of a censor who would excise all offending passages. The consequences of having to deal with censored texts, both from the outside and from self censorship, is one of the tragic outcomes of our Galus.

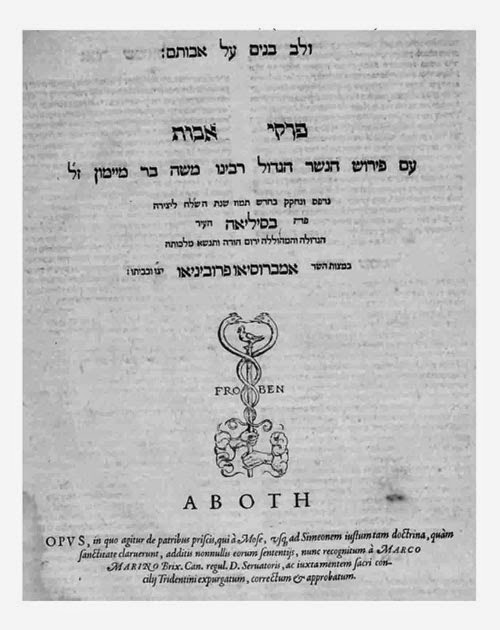

The first attempt to print the Talmud under the Papal ban was in 1578-1581 in Basel by the printer Ambrosius Froben who was allowed to print the Talmud under the lead censorship of Father Marco Marino.

Regarding the censorship efforts, Marvin J. Heller notes this was the most censored edition ever printed.[2] Stories about the founder of Christianity were deleted, and many references to anything remotely connected to Christianity were changed. When it came to Aggadic material, Raphael Nathan Nata Rabinowitz in

מאמר על הדפסת התלמודwrites that regarding material which was either a bit strange or against the Christian concepts of reward and punishment, the censor would print a short explanation about it on the page.[3]

I would like to focus on one piece of the printed Talmud which is Aggadic in nature, the comment that was made on it by one of the classic Jewish Meforshim, and the comment made on that comment by the censor. I am vexed by the following question, “what was bothering the censor?”

The piece in question is in מסכת אבות- פרק ו’-משנה י’

חמשה קנינים קנה לו הקדוש ברוך הוא בעולמו, ואלו הן, תורה קנין אחד, שמים וארץ קנין אחד, אברהם קנין אחד, ישראל קנין אחד, בית המקדש קנין אחד.

תורה מנין, דכתיב (משלי ח), יהוה קנני ראשית דרכו קדם מפעליו מאז.

There is a commentary on Avos in many of the early printed editions of Mishnayos and of the Talmud. This commentary is attributed to the Rambam in the

Soncino Napoli edition of the Mishnayos, in the

Bomberg editions, in the

Basel edition, and in the 1721 Frankfurt edition amongst others. It turns out that the commentary on the sixth chapter of Avos was not written by the Rambam as noted by the Romm 1880 edition of the Talmud, which attributes it to Rashi. [4]

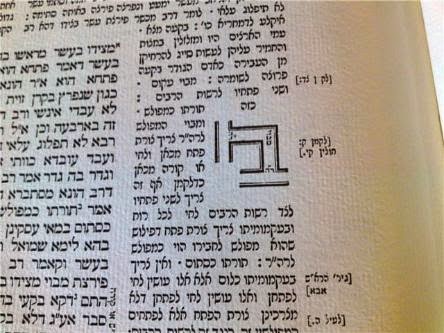

Be that as it may, this Peirush as printed in the

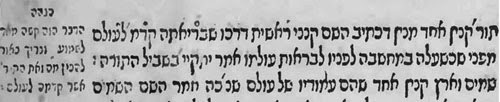

Mishnayos by Yehoshua Shlomo Soncino, Napoli 1492, states the following:

תורה קנין אחד מנין דכתיב השם קנני ראשית דרכו שבריאתה קדמה לעולם מפני שכשעלה במחשבה לפניו לבראות עולמו אמר יתקיים בשביל התורה

The creation of the Torah preceded the creation of the world, because when Hashem imagined creating the world, He said that the world should exist because of the Torah

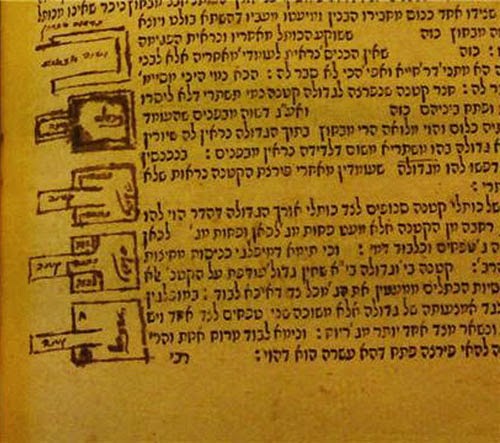

This is what it looks like there: ( from JNUL digitized books )

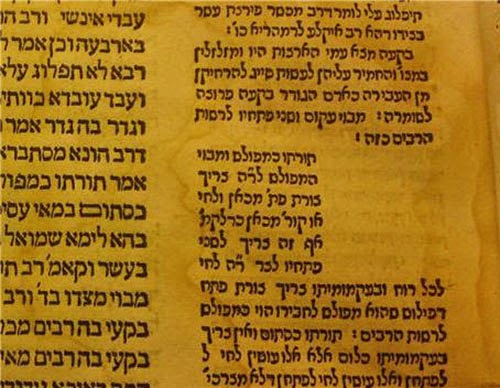

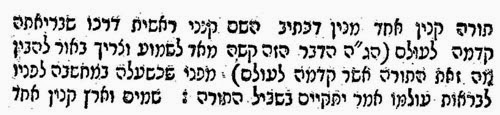

In the Bomberg Edition of 1521, it looks like this (from JNUL Digitized Books)

![]()

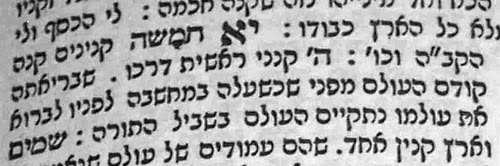

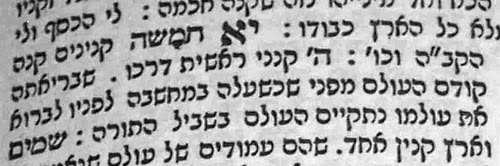

In the Basel edition of 1580, (from JNUL)

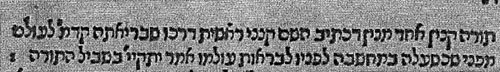

The censor seems to have a problem with the comment and put in a הג”ה on the side of the text which looks like this: (Also from JNUL)

הדבר הזה קשה מאד לשמוע, וצריך באור להבין מה זאת התורה אשר קדמה לעולם

“This thing is very difficult to understand and needs an explanation what it means when it says that ‘the Torah preceded the world'”

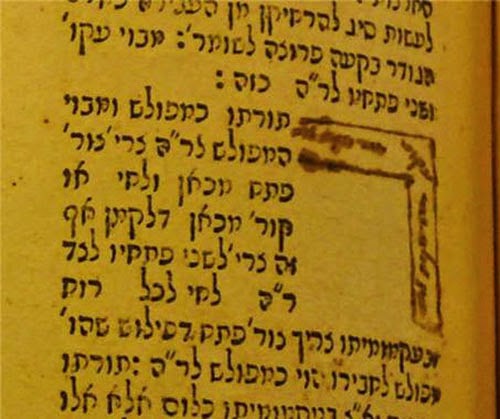

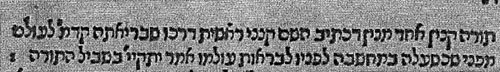

Rabinowitz states that this הג”ה of the censor found its’ way into the Benveniste Amsterdam Shas of 1644-46 , (which I saw recently in the JTS Library) and from there, it was mistakenly included in many editions afterwards.[5]

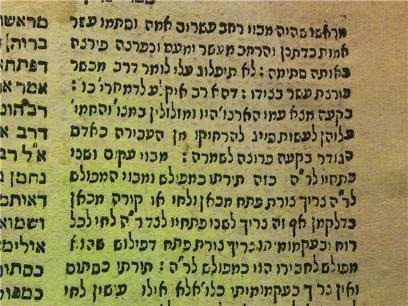

I have an edition of the Talmud printed in Frankfurt in 1721, which is the model for almost all editions that followed. [6]

In the volume which contains Maseches Avodas Kochavim U’Mazalos, we find Maseches Avos at the very end. Not only is this comment included in it, but it now made its’ way from being on the side of the page, to being right in the text of the Peirush (albeit in parentheses).

Here is what it looked like in 1721:

I saw the censor’s comment in the Sulzbach 1755 edition and the Amsterdam 1763 edition. It appears as late as the Czernowitz edition of 1843, 200 years after being mistakenly included in the Benveniste Amsterdam edition.

By the time we get to the Romm Vilna edition of 1880, thankfully the comment is gone.

The censor does not seem to have a problem with the idea that the world was created in the merit of the Torah, rather that the Torah preceded the creation of the world. Rabinowitz had stated that the censor commented on Aggadic material if it was either strange or against Christianity. The comment of the Peirush did not seem at all strange (especially when compared with other Aggadic statements) so I was curious to find out if there was anything in it that was against Christianity.

Whom to ask? I turned to a real expert, someone who wears a big black Yarmulkah, sports a Rabbinic beard, and learns Mishnayos every morning at 6:30 AM with our neighborhood hematologist/oncologist. His name is Dr. Martin Jaffee, a professor of comparative religion at the University of Washington in Seattle, and until recently, the co-editor of AJS Review. He is so good at explaining Christian theology, that one of his students once remarked to him “I wish my minister were able to explain out beliefs as well as you did”

Here were his comments:

What bothered the censor is the parallel of the primordial Torah and the Primordial Logos (Word)–Gospel of John 1:1–“In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with G-d, and the Logos was G-d.” Your censor was probably upset by the parallel. He probably wasn’t a classicist, though, or he’d have known that this Neo-Platonic idea was all over the Mediterranean and had been for several centuries. In fact, Chazal’s idea of the Torah that precedes Creation is an example of their own exploitation of Neo-Platonism in service of Torah. Surely you know the Medrash about HaKadosh Baruch Hu looking into the Torah for instructions for creating the world, “like an architect consults a plan?

That seemed simple enough. The Christian censor’s comment then made its’ way into many editions of the Talmud, to be perused by many, and discussed by some, without realizing its’ origin. I imagine a scholar in the mid 18th century who acquires a set of the Frankfurt Talmud and studies this expensive edition to his library from cover to come. He learns Maseches Avos which he finds in the back of the volume which contains מסכת עבודת כוכבים ומזלות and is happy to have the Peirush on Perek Vav which is ascribed to the Rambam. He is quite curious about a הג”ה he finds in parentheses within one of the Rambam’s comments. Who wrote this comment and what exactly was his problem? He should only know.

Notes:

[1] I have simplified this quite a bit to what most consider the immediate cause for the burning of the Talmud at that time. For a more complete discussion of this matter, I would suggest reading chapters XI and XII in Marvin J. Heller’s Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud (Brooklyn 1992 ).

[2] Id. at p. 255

[3] Maamar alHadpasat ha-Talmud with Additions, ed. A.M. Habermann (Jerusalem 2006) p. 78.

On that same page Rabinowitz writes about the Basel edition: “The Jews looked with broken hearts on what had been done to their Talmud which had been trampled upon by the censor” (my paraphrase).

[4] In the Vilna Shas, this comment appears at the beginning of Perek Vav of Maseches Avos on Daf 15A. Maseches Avos can be found in the volume that contains Avodah Zarah. I have also seen that this commentary is attributed to the Beis Medrash of Rashi.

[5] Maamar alHadpasat ha-Talmud with Additions, p.78. at the end of footnote 10.

[6] Id. at p. 111