I hope to have a few posts in the coming days discussing some of the artwork found in various haggdah. While for hundreds of years artwork played an integral part of the haggadah recently this has fell into disuse. While there are few notable exceptions to this,

Raskin,

Moss Haggadahs, this practice of richly illustrating the haggdah has been replaced with a focus on commentaries.

One of the reasons, however, the practice of illustrating the haggadah, can be found in the discussion which sheds light on the custom of pretending or assuming that Eliyahu, who according to legend, visits each home on Pesach night.

The last cup of wine poured is for Eliyahu. While originally this cup was not necessarily connected to Eliyahu, today it has become associated with him. The cup of Eliyahu is not mentioned until the 15th century. Various reasons are given. The Gra explains as there is a controversy whether one must drink 4 or 5 cups, a controversy which will be resolved only when Eliyahu comes. (Divrei Eliyahu, Parshat Va’arah p. 35). The earliest source to discuss the cup, R. Zeligman Benga (student of Mahril), says that the custom to pour a cup for Eliyahu is as the night of Passover is an auspicious night for redemption, we await Eliyahu’s coming and therefore we need a cup for him.

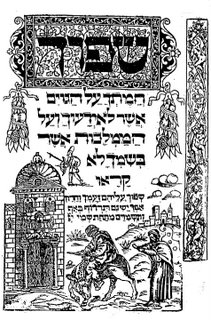

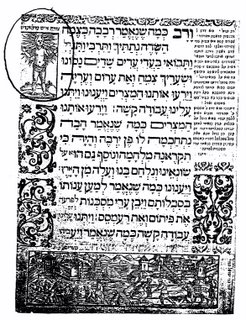

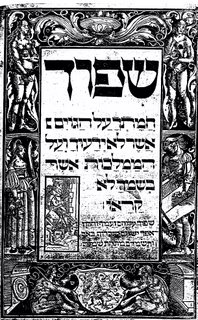

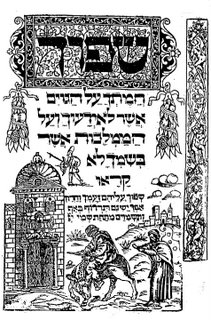

A rather interesting custom sprang up in connection with Eliyahu’s visit on Pesach night. R. Jousep Schammes (1604-1678), records that the custom in Worms was to draw depictions of Eliyahu and the Messiah in order to bring to life the belief in these figures. As you can see from the pictures on the side, this was common in the Haggadah. The first picture is a depiction of Messiah on his donkey. This was originally depicted in smaller format in the Prague 1526 haggadah, but in this edition, Mantua, 1560 is greatly enlarged. The second picture comes from the Venice 1629 hagaddah. As you can see it is again the Messiah coming in to Jerusalem, but note the prominence of the Dome of the Rock in the center.

In Frankfort they went one step further than just drawing Eliyahu and the Messiah. R. Yosef Jousep Hahn (1570-1637) says they used to hang a dummy who looked like Eliyahu or the Messiah behind the door. When they would open the door for Eliyahu the dummy would drop down and seem as if he had appeared. (He then goes on to record a long story of a dybuk who invaded the body of a women who questioned whether the Exodus happened.) It is worthwhile noting that not everyone was thrilled with these depictions. R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach (1639-1702) who became the Rabbi in Worms at the very end of his life, says these types of things only make a mockery of the seder.

However, we see from the above, that there was, at least among some, an effort to create a feeling that Eliyahu actually would visit the seder. Some did it through pictures, others through reenactments. Although today those have fallen to the wayside, it would seem the idea that Eliyahu actually drinks from the cup is a form of those methods.

Sources: Yerusalmi, Haggadah and History; Shmuel and Zev Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages, p 177-78. Minhagei Vermisai, p. פז; R. Y. Bacharach, Mekor Hayyim.