Afikoman – “Stealing“ and Other Related Minhagim*

By Eliezer Brodt

One of the most exciting parts of Seder night for kids is the “stealing” of the afikoman. Children plan well in advance when the best time would be for them to steal it, where they will hide it, as well as what they should ask for in exchange for it. Not surprisingly, toy stores do incredibly good business both during Chol Hamoed and in the days following Pesach because of this minhag. In this article I would like to trace the early sources of this minhag and also discuss rabbinic responses to it.[1]

That the minhag of stealing the afikoman was observed widely in recent history is very clear. For example, Rebbetzin Ruchoma Shain describes how she stole the afikoman when she was young; her father, Rav Yaakov Yosef Herman, promised her a gift after Yom Tov in exchange for its return.[2] Raphael Patai describes similar memories from life in Budapest before World War II.[3] In another memoir about life in Poland before the war, we find a similar description,[4] and in Alexander Ziskind Hurvitz’s Yiddish memoir about life in Minsk in the 1860s, he writes that he stole the afikoman on the first night of Pesach, that his father gave him nuts in return, and that he was warned not to steal it on the second night.[5]

Interestingly, there were occasions when the stealing of the afikoman involved adults as well. For example, in his informative memoir about life in Lithuania in the 1880s, Benjamin Gordon describes stealing the afikoman with the help of his mother,[6] and going back a bit earlier, we find that Rav Eliezer Shlomo Schick from Hungary was encouraged by his mother to steal the afikoman and to ask his father for something in exchange.[7]

But even those who recorded this minhag occasionally referred to it in less than complimentary terms. For example, in 1824 a parody called the Sefer Hakundos (literally, the “Book of the Trickster”) was printed in Vilna,[8] which describes how the “trickster” has to steal the afikoman and claim that someone else stole it.[9] In fact, this custom is even found in the work of a meshumad printed in 1856.[10]

Opposition to the Minhag

Given the implication that this minhag not only encouraged stealing but actually rewarded children for doing so, there were many who opposed it, including the Chazon Ish,[11] the Steipler,[12] Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach,[13] the Lubavitcher Rebbe[14] and Rav Tzvi Shlezinger.[15] Rav Shemtob Gaguine writes that Sefardim do not have the custom of stealing the afikoman, and he explains that this is because it is forbidden to steal even as a joke since it encourages stealing.[16] And Rav Yosef Kapach writes that this was not the minhag in Teiman as it is forbidden to steal, even for a mitzvah.[17]

Rav Aron of Metz (1754-1836) protests against this minhag in his work Meorei Or, as the goyim will say that the Jews are trying to teach their children to steal, as they did in Mitzrayim.[18] The question is, what does he mean?

In the anonymous work of a meshumad printed in 1738, we find a detailed description of the stealing of the afikoman by the youngest child and how he tries to get a reward for it from his father. He writes that the reason for this minhag is to teach the child to remember what the Jews did in Mitzrayim—that they borrowed from the Egyptians and ran away with the items.[19] This was the concern of Rav Aron of Metz. It is possible that this is why Rabbi Yair Chaim Bacharach of Worms writes in Mekor Chaim that there is reason to abolish this minhag.

How far back can this minhag be traced, and what is the source for it?

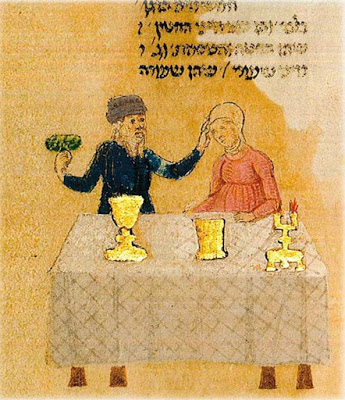

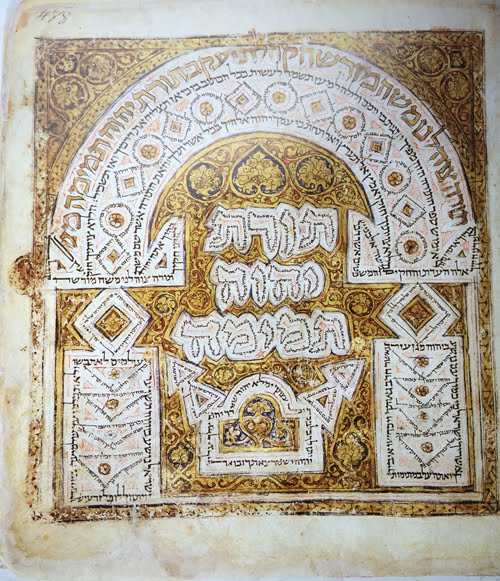

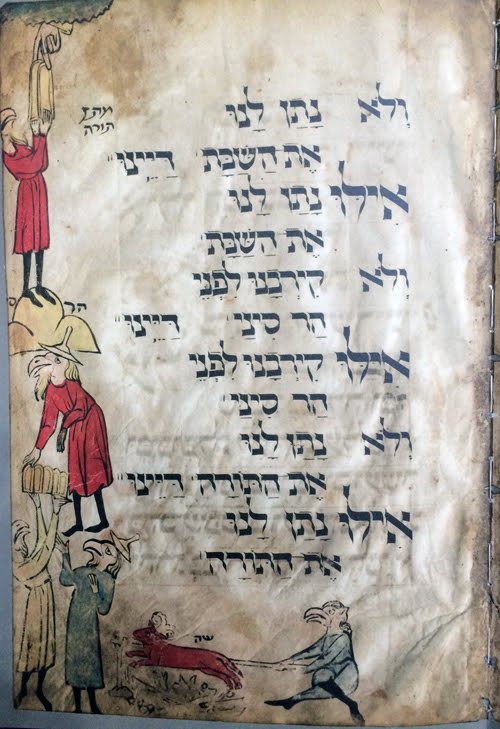

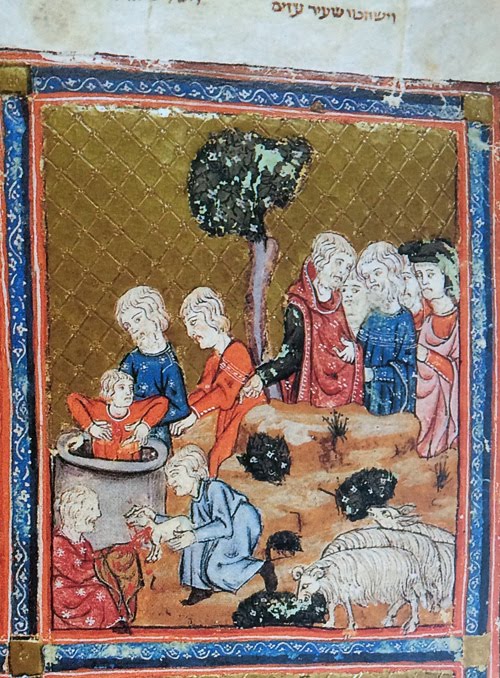

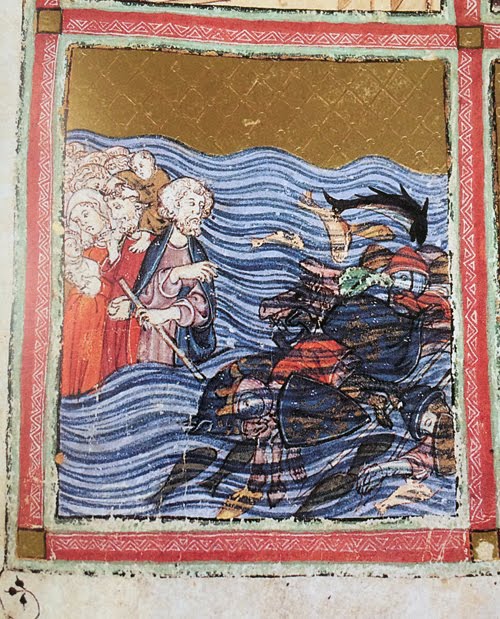

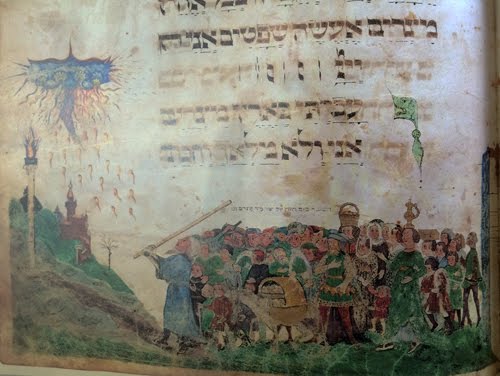

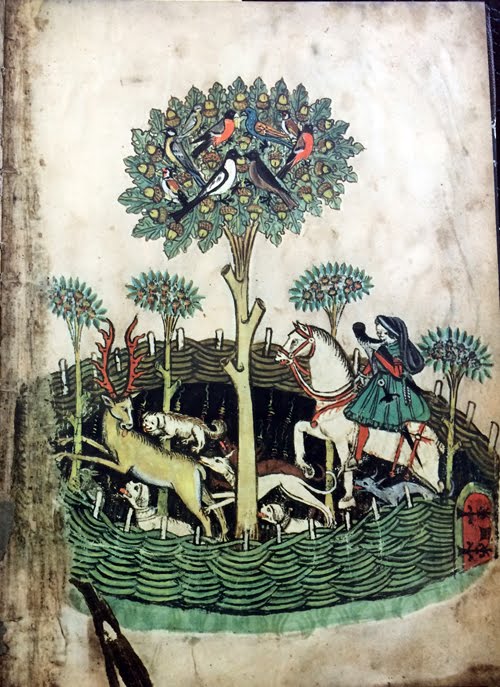

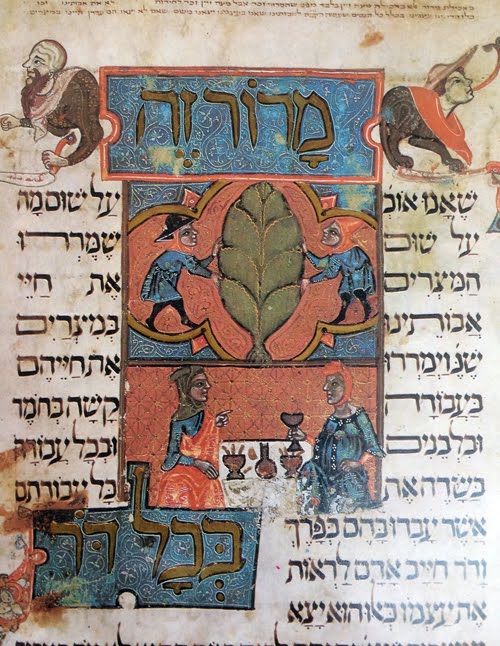

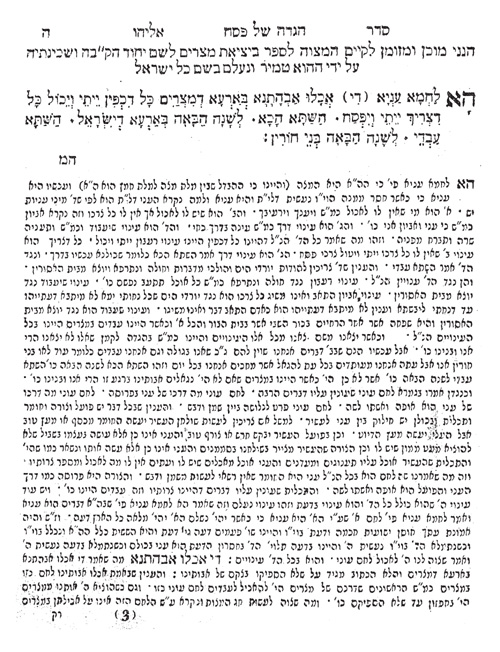

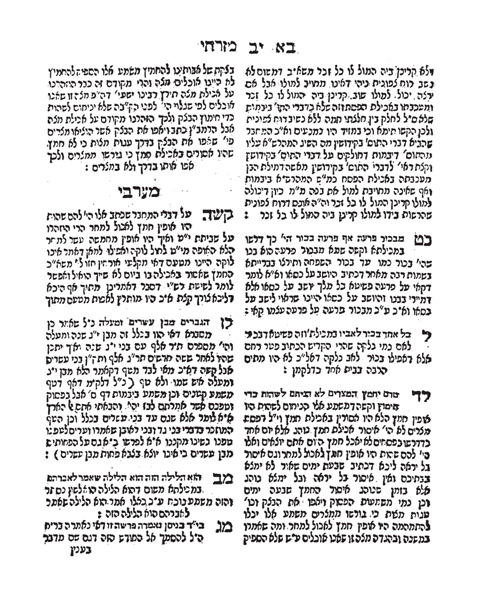

In most of the Rishonim and early poskim, in describing the part of the Seder called Yachatz, we find mention of breaking the matzah. Some go so far as to say that the leader of the Seder puts it on his shoulders and walks a bit with it (others do this only later on, when they eat the afikoman).[20] Some mention putting it under a pillow to watch it,[21] but there is almost no mention of children stealing it. The earliest source for the custom of stealing the afikoman that I have located is the illustrated manuscript Ashkenazic Haggadah, known as the Second Nuremberg Haggadah, written between 1450 and 1500. On page 6b, the boy puts out his hand to get the afikoman from his father. Later on in the Haggadah (p. 26b), in the section called Tzafun, the leader asks for the afikoman that the boy had hidden.[22] However, in almost all the many works related to the Seder, we do not find such a custom mentioned.

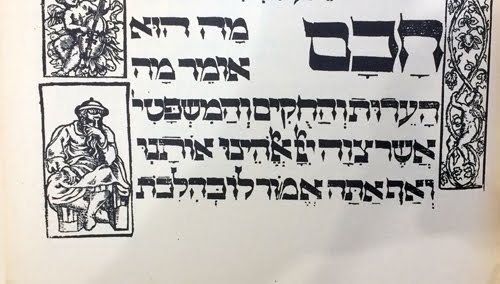

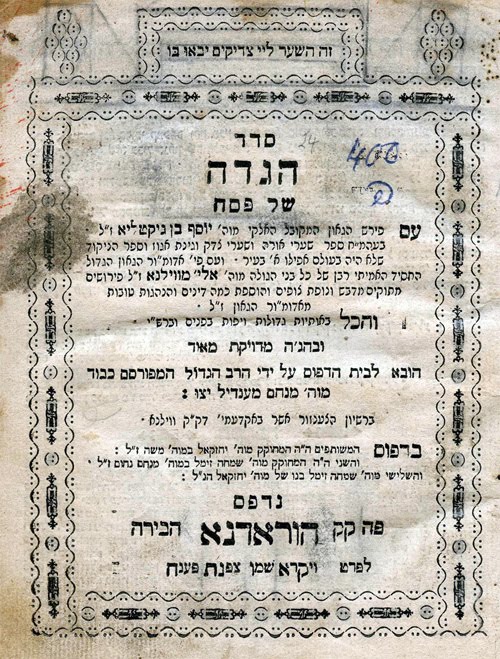

Although it’s mentioned in the Second Nuremberg Haggadah, we do not find it mentioned again after that for many years. Worth noting, for example, is that in the famous illustrated Haggadah of Prague (1526), there is no mention or picture of such a thing.[23]

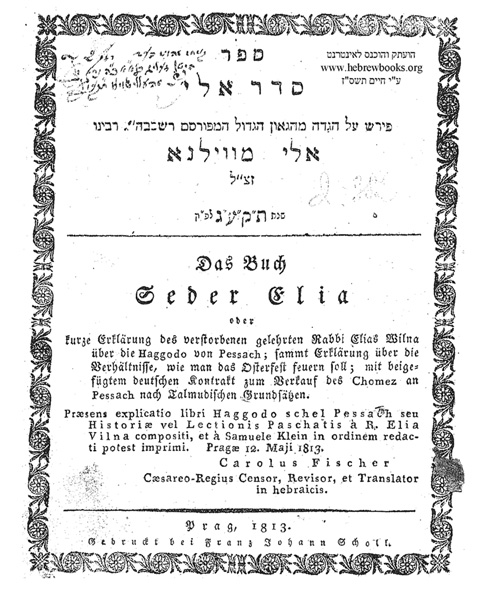

In the work Siach Yitzchak of Rav Yitzchak Chayes (1538-1610), which is a halachic work on the Seder night, first printed in 1587, there is mention of the stealing of the afikoman, but not exactly the way we do it today.[24]

Rabbi Yair Chaim Bacharach of Worms (1638-1702) writes in Mekor Chaim that the children had a custom to steal the afikoman.[25]

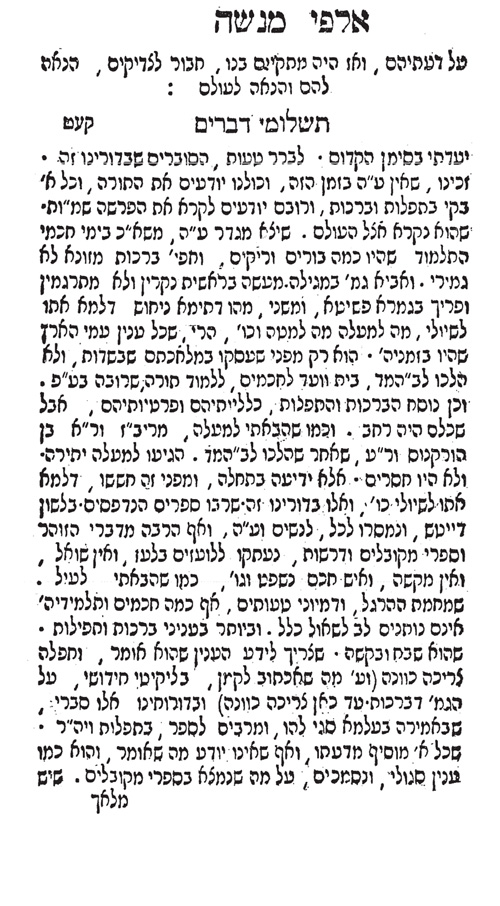

One of the earliest printed references can be found in the work Chok Yaakov on hilchos Pesach by Rabbi Yaakov Reischer (1660-1733), first printed in 1696 in Dessau. He wrote that in his area, children had the custom to steal the afikoman.[26]

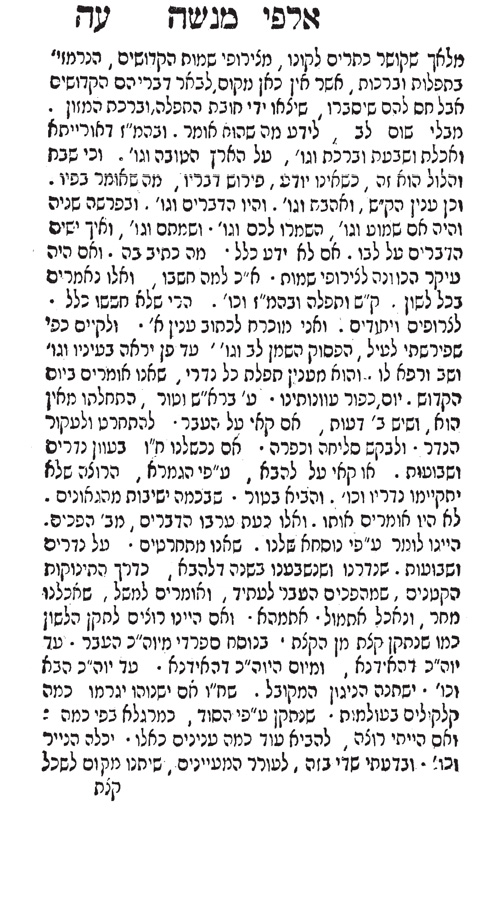

Rav Yosef Yuzpha of Frankfurt also cites this custom in his Noheg Ketzon Yosef, first printed in 1717.[27] Rav Yaakov Emden (1698-1776) cites the custom as well.[28]

Where does this minhag come from? Many Acharonim[29] point to the Gemara (Pesachim 109a), which mentions that we are “chotef” the matzos on the night of Pesach for the children.[30] What does “chotef” mean in this context? The Rishonim offer different explanations.[31] The Rambam writes that on this night one has to make changes so that the children will notice and ask why this night is different, and one answers by explaining to them what happened. The Rambam adds that among the changes we make are giving out almonds and nuts, removing the table before we eat, and grabbing the matzah from each other.[32] Rabbeinu Manoach points to the Tosefta as the source for the Rambam that “chotef” means to grab.[33] Some Rishonim, quoting the Tosefta, write clearly that it means to steal.[34]

The truth is that, based on the Rambam, we can understand where this minhag came from. The night of Pesach is all about the children. The Seder night is a time when we do many “strange” things with one goal in mind—to get the children to notice and ask.[35] The purpose of this is to fulfill the main mitzvah of the night—sippur yetzias Mitzrayim. The mitzvah of zecher l’yetzias Mitzrayim lies behind many mitzvos. The reason for this, says the Chinuch, is that Yetzias Mitzrayim was testimony that there is a God Who runs the world, and that He can change what He wants when necessary, as he did in Mitzrayim.[36] Elsewhere, the Chinuch adds that the reason Yetzias Mitzrayim is related to so many mitzvos is that in doing a variety of activities with this concept in mind, we will internalize the importance of this historic event.[37]

“Strange” Things at the Seder

Following are some of the various minhagim that are intended simply to get the children to ask questions.

The Gemara (Pesachim 109a) mentions that they gave almonds and nuts so that the children should stay awake.[38] All the various aspects of the Karpas section of the Seder, according to many, are for the purpose of prompting them to ask[39] what’s going on—from washing before eating vegetables[40] to omitting a brachah on the washing,[41] dipping the vegetable into salt water, and eating less than a kezayis,[42] breaking the matzah at Yachatz,[43] lifting the ke’arah before saying “Ha Lachma Anya,”[44] switching to Hebrew at the end of “Ha Lachma Anya,”[45] removing the ke’arah before reciting the Haggadah[46] (or removal of the table), giving even the children four cups of wine, and pouring the second cup at the beginning of the Haggadah.[47] Although numerous reasons are given for these minhagim, one common reason is that they are intended to spark the children’s curiosity, which leads to a discussion of Mitzrayim and all the miracles that took place there.

According to the Rambam, this is what lies behind the stealing of the afikoman—it is yet one more thing that we do to get the children involved and prompt them to ask questions. All this can explain another strange custom. The Chida writes that at a Seder he attended during his travels, a servant circled the ke’arah around the head of each male at the Seder three times, similar to what many do during kaparos with a chicken.[48] There are even earlier sources for such a minhag.[49]

Additional Sources in Favor of “Stealing”

At the Seder of the Chofetz Chaim and his son-in-law, the children did steal the afikoman.[50] In Persia, we find that some had this custom as well.[51] Rav Yisroel Margolis Yafeh, a talmid of the Chasam Sofer, also defends the minhag of stealing the afikoman.[52]

Earlier, I mentioned that Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach was against stealing the afikoman. Interestingly enough, his rebbe, Rav Dovid Baharan Weisfish, did allow it.[53] Rav Avigdor Nebenzahl writes that he did not understand the reasoning of his rebbe, Rav Shlomo Zalman, since it did not encourage the children to steal but simply helped them stay awake.[54]

There is a much earlier work that offers a similar premise. Rav Yosef Yuzpa of Frankfurt writes in his work Noheg Ketzon Yosef that one should not discontinue the minhag that children steal the afikoman and get something in return from their father, as this keeps them awake and they discuss Yetzias Mitzrayim.[55] And as far as the argument that stealing is never permitted, Rabbi Weingarten points to Hilchos Purim, in which we find that some level of damage is permissible for the sake of simchas Yom Tov.[56]

Other Reasons for This Custom[57]

Rabbi Yair Chaim Bacharach of Worms writes in Mekor Chaim that the reason for custom is to teach children to cherish the mitzvos.

Related to all of this is an interesting teshuvah in the anonymous work Shu”t Torah Lishmah. The author was consulted by a talmid chacham who had visited a family on the Seder night, and the head of the household put out a stack of matzah before beginning the recital of the Haggadah so that everyone could recite it over a piece of matzah. When he brought out the matzah, everyone ran to grab a piece. The guest was upset about this, and they explained to him that the purpose was to demonstrate their love for the mitzvah. The guest felt that it was an embarrassment to the mitzvah to act in such a coarse way; in addition, there is an issue not to grab bread greedily. The author of Torah Lishmah pointed to the Gemara in Chullin (133a), which suggests that since they were doing it to show their love for the mitzvah, it was not a problem.[58]

Rav Moshe Wexler, in Birkas Moshe (1902), gives a simple reason for this minhag. We are concerned that we will forget to eat the afikoman; what better way to remember than to have a child remind you since he wants to get his reward?[59]

Deeper Message Behind the Minhag

One last idea about this minhag, which is very much worth quoting, comes from Rabbi Shimon Schwab:

“I personally do not care for the term ‘stealing the matzah.’ It is un-Jewish to steal—even the afikoman! The prohibition against theft includes even if it is done as a prank (see Bava Metzia 61b)… Notwithstanding the fact that children taking the afikoman is not stealing because it is not removed from the premises, it would still be the wrong chinuch to call it ‘stealing.’ Rather, I would call it ‘hiding the matzah,’ to be used later as the afikoman, which is called ‘hidden.’

“There is an oft-quoted saying, although not found in any original halachic source, that all Jewish minhagim have a deep meaning… Thoughtful Jewish parents of old, in playing with their children, always incorporated a Torah lesson into their children’s games. Similarly, the minhag of yachatz, whereby we break the matzah into a larger and smaller piece, with each being used for its special purpose, is also deeply symbolic. The smaller piece, the lechem oni, the poor man’s bread, is left on the Seder plate, along with the maror and charoses. However, the larger piece is hidden away for the afikoman by the children, who who will ask for a reward for its return, and it is then eaten at the end of the meal.

“I heard a beautiful explanation for the symbolism of this minhag from my father. He explained that the smaller piece of matzah, the lechem oni, represents Olam Hazeh, with all its trials and tribulations. This piece is left on the Seder plate along with the maror and charoses, reflecting life in this world, with all its sweet and bitter experiences. However, the larger, main piece, which is hidden away during the Seder, to be eaten after the meal as the afikoman, represents Olam Haba, which is hidden from us during our lives in this world. The eating of this piece after the meal, when one is satiated, is symbolic of our reward in Olam Haba, which can be obtained only if we have first satiated ourselves in this world with a life of Torah and mitzvos. The children’s request for a reward before giving up the afikoman is symbolic of our reward in Olam Haba, which is granted to us by Hakadosh Baruch Hu if we have earned it.”[60]

There is an additional widespread custom of saving a piece of the afikoman for after Pesach.[61] Where does this minhag come from?

In her memoirs, Pauline Wengeroff (b. 1833 in Minsk) wrote: “In some Jewish homes, a single round matzah was hung on the wall by a little thread and left there as a memento.”[62] Mention of this custom is found in the work of a meshumad printed in 1794,[63] and another from 1856.[64] Chaim Hamberger also describes witnessing someone breaking off a piece of the afikoman and saving it as a segulah.[65] The Munkatcher Rebbe used to give out a piece of the afikoman, which some would save for the entire year.[66] In Persia, some also had the custom of saving a piece of the afikoman.[67]

In a book[68] filled with humor, which received a haskamah from Rav Chaim Berlin, a rich man complains to his friend that the mice are eating his clothes. His friend suggests that he sprinkle the clothes with the crumbs of the afikoman that he saves each year. He guarantees that the mice will not eat the clothes as the halachah is that one cannot eat anything after the afikoman!

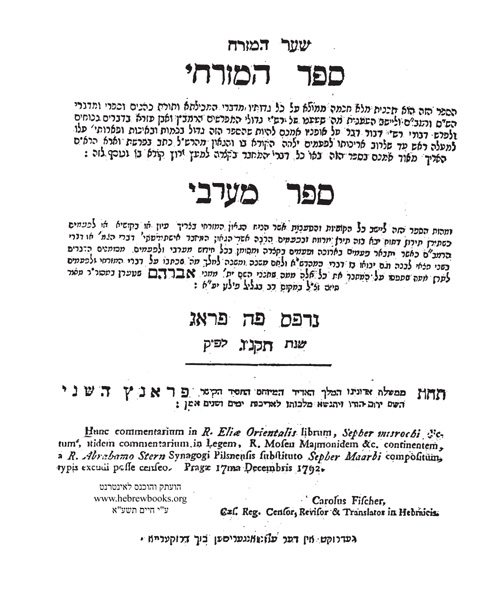

In an even earlier source, the Magen Avraham—Rav Avrohom Gombiner’s classic work on the Shulchan Aruch, first printed in 1692—he makes a cryptic statement in Hilchos Yom Tov (not in Hilchos Pesach) in a discussion of making holes in meat, saying that one should hang the afikoman in such a way that he can make a hole in it with a knife.[69] What is he referring to?

Rabbi Yaakov Reischer (1660-1733), in Chok Yaakov on hilchos Pesach, first printed in 1696, writes that there is a custom to break off a piece of the afikoman and hang it, and he points to this Magen Avraham as proof.[70] Neither of these sources gives us insight into the reason for the practice, but it is clear that it is a segulah done with the afikoman.

The answer may be found in another work of Rabbi Yaakov Reischer. He was asked about his thoughts on the Kitzur Shlah, who writes that there is a problem with hanging the afikoman since it is a bizayon [disgrace] for the food, which is a halachic issue.[71] Rav Reischer says that it is not an issue since it serves to remind us of Yetzias Mitzrayim. He adds that his father and teachers observed this custom.[72]

Rabbi Yair Chaim Bacharach of Worms also writes that the reason for the minhag to hang a piece of the afikoman is zecher l’yetzias Mitzrayim.[73]

But why isn’t there an issue of bizui ochlin? Perhaps we can understand it based on Rav Avigdor Nebenzahl’s[74] explanation of the general issur of bizui ochlin, which is that bread is a special gift that Hashem gives us from Olam Haba so it is prohibited to use it in an embarrassing way. However, here one is using it for the mitzvah of zecher l’yetzias Mitzrayim, so maybe that’s why Rav Reisher held that it was not an issue.

From these sources it appears that hanging the matzah has nothing to do with any segulah but is simply zecher l’yetzias Mitzrayim.

The Kitzur Shlah, however, suggests that if one wants to observe this minhag, he should not hang the piece of afikoman but should carry it around with him. He adds that this segulah is a protection from thieves.[75] Rabbi Yair Chaim Bacharach of Worms also mentions that the piece of afikoman is a segulah for protection when traveling, but he does not quote a source for this.

In other early segulah sefarim, we find different segulos associated with the afikoman. In a rare work first printed in 1646, we find that it protects one from mazikim. At the end of the same work, the author writes that it can protect one from drowning at sea[76]; Rav Binyamin Baal Shem makes the same statement.[77] Rabbi Zechariah Simnar’s Sefer Zechirah, first printed in 1709, states that the piece of afikoman protects one from mazikim. This last source is an additional reason for the widespread observance of the custom because the sefer was extremely popular in its time and was reprinted over 40 times.[78]

One famous personality who actually used this segulah was Sir Moses Montefiore. When he found himself in the midst of a terrible storm, he cast a piece of afikoman into the sea. His family used to commemorate this miracle each year.[79]

In the anonymous work of a meshumad printed in 1738, he says it is used to ward off the evil eye.[80] Rav Yisachar Shlomo Teichtal has a very interesting teshuvah on this segulah. He writes that in the Shulchan Aruch it appears that the afikoman has all the dinim of the korban Pesach; with that comes the problem of leaving behind even one piece. He says that one should leave a piece behind for this segulah only from the matzah of the second night. He says that the people in Eretz Yisrael should save a regular piece of matzah. He then cites the Yosef Ometz, who writes that he made sure not to lose one crumb of the afikoman, so how could one possibly save a piece for the entire year?[81] His suggestion at the end is that it is better to save a regular piece of matzah.

Rav Chaim Hakohen, a talmid of Rav Chaim Vital, writes in his work Tur Barekes that there is a special segulah to save and hang a piece of matzah for the entire year and that it protects one from mazikim.[82] This practice is also cited in the very popular anonymous work Chemdas Yamim, which was first printed in 1731.8[3] Rabbi Moshe Chagiz (1671-1751) writes the same about the segulah, [84] as does Rav Dunner.[85] All of these sources appear to say that the segulah is not specifically associated with a piece of the afikoman.

Until 2010, these was the array of earlier sources known for this custom. In 2010, a fascinating manuscript of Rav Chaim Vital (1543-1620) was printed for the first time—Sefer Hape’ulos.[86]

Rav Chaim Vital is best known in the realm of Kabbalah; he was the primary student of the Arizal, entrusted with disseminating his teacher’s works.

What makes Sefer Hape’ulos especially interesting is that we see Rav Chaim Vital in a different light than he was previously known. In the first part of this work we see him as a doctor of sorts. He provides remedies to people for all kinds of illnesses—asthma, infertility, headaches, toothaches and many other conditions. Much of his advice was based on segulos and the like. In this work, he shows a familiarity with medical procedures of that period. He quotes advice that he had read in various medical works. There is also a section on alchemy.

The whereabouts of the actual manuscript are a mystery.

Rumors are that it is being sold page by page as segulah, and each page fetches a large sum of money. But copies of the manuscript are accessible on various databases.

In this work, Rav Chaim Vital writes that to calm the sea in a storm, one should take a kezayis of the afikoman and throw it into the sea.[87]

According to this statement, we see that Rav Vital does not agree with the sources saying that the afikoman should be regarded as regular matzah. Furthermore, we see that he was not concerned with Rav Teichtal’s issues as he was in Eretz Yisrael and he still said the afikoman should be used.

Burning With the Chametz

One last aspect of the treatment of the afikoman comes from Rav Schick, who says that since the afikoman is eaten as a zecher of the korban Pesach, we should keep a piece of it to burn with the chametz in order to remind us that any leftovers of the korban Pesach were to be burned.[88] Rav Dunner did the same.[89] The aforementioned work of a meshumad, printed in 1856,[90] mentions this aspect of the custom.

* A version of this article was printed in April of last year in Ami Magazine.

[1] For sources on this topic that helped me prepare this article R’ Moshe Katz, Vayaged Moshe, pp. 118-120; R’ Moshe Weingarten, Seder Ha-Aruch 1 (1991), pp. 336-338; R’ Y. Lieberman, Chag Hamatzos, pp. 458-460; R’ Avrohom Feldman, Halacha Shel Pesach, pp. 299-302; R’ Chaim David Halevi, Shonah Bishonah (1986), pp. 144-148; R’ Tuviah Freund, Moadim Li-Simcha (Pesach), pp. 340-354 [=Tzohar 2 (1998, pp. 196-206]; Pardes Eliezer, pp. 158-172; S. Reiskin, Yedah Ha-Am, 69-70 (2010), pp. 114-121 [Thanks to R’ Menachem Silber for this source]. See also, R’ Melamed, Hadoar 69 (1990), pp. 13-14.

[2] Ruchoma Shain, All for the Boss, (Young readers edition) (2008), pp. 6-7.

[3] Raphael Patai, Apprentice in Budapest: Memories of a world that is no more (1988), p. 156.

[4] Norman Salsitz, A Jewish Boyhood in Poland: Remembering Kolbuszowa (1999), pp. 166-167.

[5] A. Z. Hurvitz, Zichronot Fun Tzvei Dorot (1935), p. 138.

[6] Benjamin Lee Gordon, Between Two Worlds: The Memoirs of a Physician (2011), p. 24.

[7] R’ Shlomo Tzvi Schueck, Seder Haminhagim, (1880) p. 69b. About R’ Schueck, see Adam Ferziger, “The Hungarian Orthodox Rabbinate and Zionism: The Case of R. Salamon Zvi Schück”, Eleventh World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem, Israel, July 1993). I hope to return to him in a future piece.

[8] See the critical edition of this work printed in 1997, p. 67.

[9] P. 64.

[10] H. Baer, Ceremonies of Modern Judaism (1856), p. 149.

[11] R’ Z. Yavrov (ed.), Ma’aseh Ish Vol. 5 (2001), p. 19.

[12] R’ A. L. Horovitz (ed.), Orchos Rabbeinu Vol. 2 ( p. 78.

[13] R’ Y. Turner & R’ A. Auerbach (ed.), Halichos Shlomo (Moadei Hashanah: Nissan-Av) (2007) p. 260; R’ T. Freund, Shalmei Moed, (2004) p.400.

[14] R’ M. M. Schneersohn, Haggadah Shel Pesach Im Likutei Tamim Vol. 1 (2014), p. 11. See also p. 179.

[15] R’ Y. Shlezinger, Meorot Yitzchak (2012) p. 345.

[16] R’ S. Gaguine, Keser Shem Tov Vol. 3 (1948), p. 176.

[17] Halichos Teiman (1968), p. 22. See also, R’ Razabi, Hagadah Pri Etz Chaim, p. 337-338; R’ Harari, Mikroei Kodesh, p. 209.

[18] Meorei Or, Od Lomoed, p. 178a. The Orchos Chaim (Spinka). 473:19 quotes this piece. See R’ Yisachar Tamar, Alei Tamar, Moed 1, p. 311. On this work see the important article of Yakov Speigel, Yerushaseinu 3 (2009, pp. 269-309. About this specific piece see Ibid, pp. 279-289; R’ Dovid Zvi Hillman, Yeshurun 25 (2011), p. 620.

[19] Gamliel Ben Pedahzur, The Book of Religion, Ceremonies and Prayers of the Jews, London 1738, pp. 54-55. On this work see C. Roth, Personalities and Events in Jewish History, pp.87-90, David B. Ruderman, Jewish Enlightenment in an English Key, Princeton University Press 2000, pp. 242-49.

[20] See Hanaghot HaMarshal, pp. 10-11; Magen Avraham, 473:22; Chidushel Dinim Mei-Hilchos Pesach, p. 38. See Rabbi Chaim Benveniste, Pesach Meuvin, 315; Vayagid Moshe, pp. 116-117. There are numerous sources for putting on short skits at the seder I hope to return to this in the future.

[21] See Rabbi Yechiel Heller, Or Yisharim, p. 3b; R’ Reuven Margolis, Haggdas Baer Miriam (2002), p, 26.

[22] The Haggadah is now online here (http://jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/mss-pr/mss_d_0076/). See Bezalel Narkiss and Gabriella Sed-Rajna article about this Hagdah available there. Thanks to Rabbi Mordechai Honig for pointing me to this source.

[23] On this haggadah see Y. Yudolov, Otzar Haggadas, p. 2, # 7-8. See also Rabbi Charles Wengrov, Haggadah and Woodcut, (1967), pp, 69-71; the introduction to the 1965 reprint of this Haggadah; Yosef Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, plate 13; See also Yosef Tabori, Mechkarim Betoldos Halacha (forthcoming), pp. 461-474. I hope to return to this Hagdah in a future article.

[24] Sich Yitzchack, p. 21a. About this Gaon see the Introduction of R’ Adler in his recent edition of his Pnei Yitzchchak- Apei Ravrivi.

[25] Mekor Chaim, Siman 477. This incredible work was first printed from manuscript in 1988.

[26] Chok Yaakov, 472:2. About him see S. Shilah, Asufot 11 (1998), pp. 65-86.

[27] Noheg Ketzon Yosef, p. 222.

[28] See his siddur, volume 2, p. 48. This comment is from the recent additions printed from the manuscript of his siddur.

[29] The first to tie it to this Gemarah was Chok Yakov (1696), R’ Yakov Emden; R’ Yedidya Thia Weil, Marbeh Lisaper, (1791), p. 7a; R’ Shimon Sofer (son of the Chasam Sofer), Mectav Sofer p. 110b; R’ Tzvi Segal, Likutei Tzvi, (1866) p. 28; R’ Shlomo Tzvi Schueck, Seder Haminhaghim, (1880) p. 69b; Sefer Matamim, p. 154; Meir Ish Sholom, Meir Ayin Al Seder Vehagadah Shel Leli Pesach, (1895), p. 34; Rabbi Yeshayah Singer, Mishneh Zichron, (1913) p. 180; R. Avraham Eliezer Hershkowitz, Otzar Kol Minhaghei Yeshrun (St. Louis, 1918), p. 136. See also Daniel Goldschmidt, Haggadah Shel Pesach (1948), p. 22 [This piece does not appear in his later edition]. See the interesting Teshuvah on this from R’ Munk, Pas Sudecha, Siman 51.

[30] Related to this, see Shu”t Torah Lishmah, #138 where he describes a custom on the Seder night.

[31] See Rashi; Rashbam; Riaz.

[32] Rambam, Chometz Umatzah 7:3.

[33] See R’ Saul Lieberman’s Tosefta Kifshuto, Pesachim, p. 653; R’ Yisachar Tamar, Alei Tamar, Moed 1, p. 311; Meir Ish Sholom, Meir Ayin Al Seder Vehagadah Shel Leli Pesach, (1895), pp. 34-35; Yosef Tabori, Pesach Dorot, p. 254; Shmuel & Zev Safrai, Haggadas Chazal, (1998), pp. 47-48.

[34] See Rashbam; Sefer HaMichtam; Maharam Halewa; Rabbenu Yerchem; Meiri. See also Ri Melunel and the Nimukei Yosef. See also Mahril, p. 114.

[35] This topic is dealt with at great length in Rabbi Mordechai Breuer’s Pirkei Mo’adot, pp. 171-192; Shama Friedman, Tosefta Atiktah, pp. 439-446. See also Rabbi Yosef Dubovick’s unpublished paper on the topic [many thanks to him for making it available to me]. See also Hagada Shel Pesach, Mesivtah, pp. 101-107. For more on this see the excellent recent work of Dovid Henshke, Ma Nishtna (2016), pp.271-299, 397-405.

[36]. See Chinuch Mitzvah 10.

[37] Chinuch Mitzvah 20.

[38] See R’ Chaim Berlin, Nishmat Chaim, p. 179. Yechezkel Kotik describes in his memoirs (Ma She’ra’iti, p. 164) getting nuts on Erev Pesach. See also Pauline Wengeroff, Rememberings, p. 44 who also describes getting nutson Pesach.

[39] See R’ Chaim Berlin, Shut Nishmat Chaim (Bei Brak), Siman 50.

[40] Chock Yakov, 473:28 see also Mahril, p. 98; Yosef Tabori, Pesach Dorot, (1996), pp. 212-244; R’ Yosef Schachar, Hod Vhadar Kevodo, pp. 124-125 [A Letter of Rabbi Chaim Berlin]; my Bein Keseh La-asur, pp. 148-153.

[41] See Yosef Tabori, Pesach Dorot, ibid.

[42] See Drasha of the Rokeach, p. 97

[43] Seder Hayom, p. 153

[44] Drasha of the Rokeach, p.98.

[45] Drasha of the Rokeach, p.98.

[46] See Drasha of the Rokeach, p. 9. But see Magan Avrhom 473:25 and Chock Yakov 473:33.

[47] See Magan Avrhom, 473:27; Seder Haaruch, 1, p. 388-390.

[48] Maagal Tov, pp. 62. On this work see my article in Yeshurun 26 (2012) pp. 853-874 and my earlier article in Ami Magazine, September 27, 2012 Is the Zoo Kosher?

[49] See the collection of sources in Rabbi Tovia Preshel, Or Yisroel 15 (1999),pp. 149-151; Rabbi Yisroel Dandorovitz, Yechalek Shalal (2014), pp. 92-98. It appears that the Barcelona Haggadah, produced after 1350, is the earliest record of the custom to place the Seder Plate on someone’s head during the recitation of Ha Lahma Anya [Thanks to Dan Rabnowitz for this source].

[50] Hagadas HaGershuni, p. 58

[51] Yehudei Poras, pp. 25, 26-27.

[52] Shut Mili D’avos (3:14).

[53] Orech Dovid, p. 107

[54] Hagadah Yerushlyim Bemoadeah,p. 55. See also R’ Harari, Mikroei Kodesh, p. 209

[55] Noheg Ketzon Yosef, p. 222.

[56] Seder Haaruch 1, p. 338. However see the Aruch Hashulchan 696:10 who says today we are not on such a level.

[57] For additional reasons see R’ Shimon Sofer (son of the Chasam Sofer), Mectav Sofer p. 110b; R’ Yisroel Margolis Yafeh, Shut Mili D’avos (3:14); Rabbi Yeshayah Singer, Mishneh Zichron, (1913) p.67a.

[58] Shut Torah Lishma, #138. On this work see: M. Koppel, D. Mughaz and N. Akiva (2006), New Methods for Attribution of Rabbinic Literature Hebrew Linguistics: A Journal for Hebrew Descriptive, Computational and Applied Linguistics; M. Koppel, J. Schler and E. Bonchek-Dokow (2007), Measuring Differentiability: Unmasking Pseudonymous Authors, JMLR 8, July 2007, pp.1261-1276; R’ Y. Liba, Shevet MeYehudah, pp. 213-236; R’ Yakov Hillel, Ben Ish Chai (2011), pp. 410-422; (excellent) intro-

duction to the new edition of this work; Levi Cooper, A Bagdadi Mystery: Rabbi Yosef Chaim and Torah Lishmah, JEL 14;1 (2015), pp 54-60.

[59] Birchat Moshe, pp. 15-16

[60] Rav Schwab on Prayer, pp. 542-543.

[61] R’ Menachem Kasher, Torah Shlemah, 12:286; Rabbi Moshe Weingarten, Seder Ha-Aruch 2 pp.244-245; Pardes Eliezer, pp.172-179. The most recent discussion of this custom is by R’ Bentzion Eichorn where he devoted a complete work called Simchat Zion (2008) (73 pps.) devoted to the many aspects of this minhag. See also D. Sperber, The Jewish Life Cycle, p. 585.

[62] Rememberings, p. 45.

[63] H. Isaacs, Ceremonies, Customs Rites and Traditions of the Jews, London 1794, pp. 111.

[64] H. Baer, Ceremonies of Modern

Judaism, Nashville 1856, p. 149.

[65] Tzefunot 11 (1991), p.97.

[66] Darchei Chaim Ushalom, pp. 193-194.

[67] Yehudei Poras, p.27.

[68] Osem Bosem, p. 35.

[69] Siman 500:7. For a possible early source for this dating to 1550 see Y. Yuval, Two nations in your Womb, p.245.

[70] Chok Yakov, 477:3.

[71] Kitzur Hashilah, p. 67a. See Hatzofeh Lichochmas Yisroel 9 (1925), pp.235-241 for an additional problem with observing this custom.

[72] Shut Shevous Yakov, 3:52.

[73] Mekor Chaim, Siman 477.

[74] Yerushalayim BeModeah (Purim), p. 258.

[75][76] Derech HaYashar, p. 8, p. 42.

[77] Amtachas Binyomin, p. 18.

[78] Sefer Zechira, p. 271. On this work see my Likutei Eliezer, pp. 13-25.

[79] See Cecil Roth, Personalities and Events in Jewish History, p. 85. See also Abigail Green, Moses Montefiore: Jewish Liberator, Imperial Hero (Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press, 2010, pp. 82-83 and 447 n.104. [Thanks to Menachem Butler for this last source].

[80] Gamliel Ben Pedahzur, The Book of Religion, Ceremonies and Prayers of the Jews, London 1738, p.78. Earlier on p. 55 he mentions some carry it with them as a segulah when traveling to stop a storm.

[81] Mishnat Sachir, # 122.

[82] See also R’ Dovid Zechut, Zecher Dovid, 3:27, p. 183.

[83] Chemdas Yomim, Pesach, p. 26 b. On this work see my Likutei Eliezer, p. 2.

[84] Eleh hamitzvos 19, p. 58.

[85] Minhagehi Mahritz Halevi, p. 167-168.

[86] On this work see Gerrit Boss, extensive article “Hayyim Vital’s Practical kabbalah and Alchemy; a 17th Century book of secrets” in the Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, Volume 4, pp. 54-112. See also my Likutei Eliezer, pp.46-89.

[87] Sefer Hape’olot p. 241. In 2015 a beautiful haggadah, Hagaddas Medrash BiChodesh, (2015), was printed for the first time of R’ Eliezer Foah (died 1658) talmid of the Remah Mi Pano where he also brings this segulah of throwing it in to the sea (pp. 19-20). The editor incorrectly writes that this is the first source for this segulah.

[88] Siddur Rashban, 33b.

[89] Minhagehi Mahritz Halevi, p. 167-168.

[90] H. Baer, Ceremonies of Modern Judaism, Nashville 1856, p. 149.